Introduction

The term “short circuit” appears frequently in discussions about electrical safety, fire investigations, and equipment failures. Most people have heard that short circuits are dangerous, and many have experienced the sudden loss of power when a short circuit trips a circuit breaker. Yet despite its common usage, the term remains poorly understood by many who encounter it. What exactly happens during a short circuit? Why does an unintended connection between two wires create such immediate and severe consequences? And most importantly, how can you recognize and prevent short circuits to protect both your equipment and your safety?

A short circuit represents one of the most dangerous fault conditions in electrical systems. When a short circuit occurs, current can increase to hundreds or thousands of times normal operating levels within milliseconds, generating intense heat, creating fire hazards, damaging equipment, and potentially causing injury or death. The sudden, catastrophic nature of short circuit failures makes understanding them essential for anyone working with electrical systems or using electrical devices.

This comprehensive guide will build your understanding of short circuits from fundamental electrical principles, exploring what defines a short circuit, the multiple mechanisms that cause them, why they are so immediately dangerous, how protective devices detect and interrupt them, and most importantly, how to design, install, and maintain electrical systems to prevent short circuits from occurring. Rather than presenting isolated facts, we will develop an integrated understanding that connects short circuit behavior to the fundamental concepts of voltage, current, and resistance you have already learned.

Defining the Short Circuit

Understanding what constitutes a short circuit requires examining both what short circuits are and what they are not, developing a precise definition that clarifies this critical fault condition.

The Technical Definition

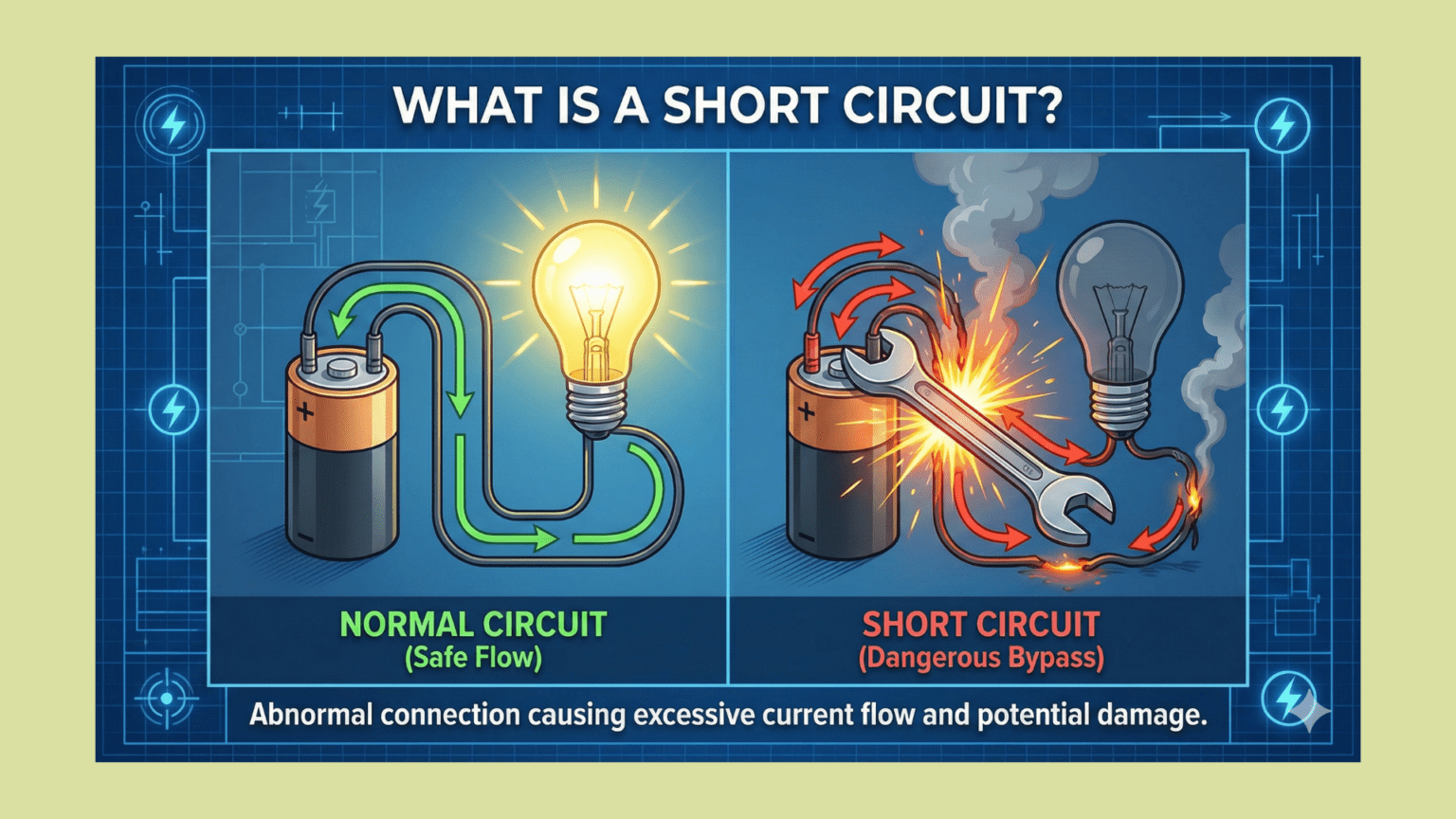

A short circuit occurs when current bypasses the intended load through an unintended low-resistance path, creating a direct or nearly direct connection between different voltage levels in a circuit. This unintended path “shorts out” the normal circuit operation, creating a shorter pathway for current that bypasses the components designed to limit current flow to safe levels.

The key element in this definition is the low-resistance unintended path. In a properly functioning circuit, current flows through designed components like resistors, motors, or light bulbs that provide resistance to limit current to appropriate levels. When an unintended low-resistance connection forms between the power source terminals or between different voltage levels, current bypasses these current-limiting components, flowing through the very low resistance of the short circuit path instead.

The magnitude of short circuit current depends on the voltage source strength and the total impedance in the short circuit path. In the limiting case of a perfect short circuit with zero resistance, current would theoretically approach infinity, limited only by the power source’s internal impedance. Real short circuits have some resistance from wire resistance, contact resistance, and arc resistance, but this resistance is typically very low compared to normal circuit resistance, allowing currents tens, hundreds, or thousands of times greater than normal operating current.

What Short Circuits Are Not

Distinguishing short circuits from other circuit faults prevents confusion and helps identify actual short circuit conditions. An open circuit, where the current path is broken completely, is the opposite of a short circuit. Open circuits prevent current flow entirely. Short circuits allow excessive current flow through unintended paths.

An overload condition, where too many devices draw current simultaneously or a single device draws more current than designed, differs from a short circuit. Overloads involve current flowing through intended paths but at higher-than-designed levels, typically 10-50% above normal. Short circuits create current flows many times higher than normal through unintended paths, often hundreds or thousands of percent above normal operating current.

A ground fault, where current flows through an unintended path to earth ground, may or may not be a short circuit depending on the resistance of the ground path. A low-resistance ground fault effectively creates a short circuit between the hot conductor and ground. A high-resistance ground fault might not draw enough current to be considered a short circuit but still presents serious shock hazards.

The “Short” in Short Circuit

The term “short circuit” derives from the unintended path being shorter than the intended circuit path. In a flashlight, the intended path runs from the battery through a switch, through the light bulb’s resistance, and back to the battery. If a wire accidentally connects the battery terminals directly, current takes this shorter path, bypassing the bulb entirely. This shorter pathway gives short circuits their name.

However, physical path length is not the defining characteristic. A long wire connecting two voltage levels can still create a short circuit if its resistance is very low compared to the intended circuit resistance. What matters is the electrical shortness, the low impedance that allows current to bypass normal circuit elements, rather than physical shortness.

The Physics of Short Circuit Currents

Understanding why short circuits produce such extreme currents requires examining the relationship between voltage, resistance, and current that governs all electrical behavior.

Ohm’s Law and Maximum Current

Ohm’s Law states that current equals voltage divided by resistance: I = V / R. This simple relationship reveals why short circuits are so dangerous. For any given voltage, decreasing resistance increases current proportionally. If we halve resistance, we double current. If we reduce resistance to one-tenth its original value, current increases tenfold.

In normal circuits, designed resistance limits current to safe, useful levels. A 60-watt incandescent bulb operating at 120 volts has approximately 240 ohms of resistance, limiting current to 0.5 amps. Now consider what happens if a wire with 0.1 ohm resistance accidentally connects the two voltage levels. The same 120 volts divided by 0.1 ohm produces 1,200 amps—2,400 times the normal operating current.

This dramatic current increase happens instantaneously when the short circuit forms. There is no gradual ramp-up, no warning period. The moment the low-resistance path connects, current jumps to the level determined by voltage divided by the short circuit path resistance. This sudden onset is one reason short circuits are so destructive.

Source Impedance and Available Fault Current

The maximum current a short circuit can produce is limited by the source impedance—the internal resistance and reactance of the power source supplying the fault. A small battery has relatively high internal resistance, limiting short circuit current to perhaps tens or hundreds of amps even when dead-shorted. An automotive battery with very low internal resistance can deliver thousands of amps when shorted. The electrical grid, backed by massive generators, can supply tens of thousands of amps or more at the point of use.

Available fault current, the maximum current that can flow during a short circuit, becomes a critical specification for electrical equipment. Circuit breakers must interrupt available fault current without exploding or failing to clear the fault. Conductors must withstand the magnetic forces and thermal effects of fault current for the brief period before protective devices operate. Transformers and generators must tolerate the mechanical stresses of fault current until protection isolates the fault.

Calculating available fault current requires knowing the source voltage and the total impedance in the fault path, including source impedance, conductor impedance, and fault impedance itself. Electrical engineers perform these calculations to properly specify protective equipment and ensure safe electrical installations.

The Time Factor

Short circuit current does not necessarily remain constant over time. In AC systems, fault current may include a transient DC component that gradually decays, with total current initially higher than the steady-state value. Inductive circuits may experience current that builds gradually toward its steady-state value, though this buildup typically occurs within a few cycles in power frequency circuits.

For most short circuits, the critical period is the first few milliseconds to few cycles after fault occurrence. This is when current reaches maximum values and when protection must operate to limit damage. Modern circuit breakers detect and interrupt faults within one to three cycles (16-50 milliseconds at 60 Hz), limiting the duration of dangerous fault current flow.

How Short Circuits Occur

Short circuits arise from various mechanisms, each creating unintended low-resistance connections between different voltage levels. Understanding these mechanisms helps identify risks and implement prevention strategies.

Insulation Breakdown

Electrical conductors are separated by insulating materials that prevent current flow between them. Wire insulation, equipment enclosures, air gaps, and insulating supports all provide necessary isolation. When these insulators fail, conductors at different voltages can come into direct contact, creating short circuits.

Insulation degradation occurs through multiple mechanisms. Age causes insulation to become brittle and crack, particularly in environments with temperature extremes or ultraviolet exposure. Mechanical damage from abrasion, crushing, or cutting compromises insulation integrity. Chemical exposure can dissolve or degrade insulating materials. Moisture infiltration reduces insulation resistance, eventually allowing current leakage that can escalate to short circuits.

Thermal stress accelerates insulation failure. When conductors carry excessive current or operate in high-temperature environments, heat degrades insulation more rapidly. This creates a dangerous positive feedback: overheating damages insulation, damaged insulation allows higher current, higher current creates more heat, and the cycle continues until catastrophic failure occurs.

Voltage stress also degrades insulation over time. Applying voltage near an insulator’s rated limit causes gradual deterioration through partial discharge, corona effect, and electrical treeing—progressive breakdown channels that propagate through insulation until complete failure occurs. Operating equipment at voltages well below insulation ratings extends insulation life significantly.

Physical Damage and Foreign Objects

Mechanical impacts can damage wiring and create short circuits. Nails driven through walls during construction or picture hanging can penetrate electrical cables, directly connecting hot and neutral conductors or hot conductors to ground. Rodents chewing through wire insulation create similar direct connections. Vibration in machinery can cause wire chafing where conductors rub against metal enclosures or structural members.

Conductive foreign objects falling across exposed conductors create instant short circuits. A metal tool dropped across battery terminals, a wire strand bridging circuit board traces, or a conductive liquid spilled into electrical equipment can all create low-resistance paths where none should exist. These sudden-onset short circuits often catch users by surprise because they occur without warning and in seemingly safe circumstances.

Loose connections contribute to short circuit risk through a gradual process. Initially, a loose connection creates high resistance that generates heat. This heat oxidizes metal surfaces, increasing resistance further. Eventually, the connection may fail completely, creating arcing that can weld nearby conductors together or deposit conductive carbon that creates short circuit paths. Properly tightened and maintained connections prevent this failure mode.

Water and Moisture Intrusion

Water’s conductivity varies with dissolved ions, but even relatively pure water has sufficient conductivity to create dangerous current paths. When water infiltrates electrical equipment, it creates conductive bridges between conductors at different voltages, effectively short-circuiting the system.

The short circuit current through water initially may be limited by water’s resistance, but this current generates heat that evaporates water, concentrating dissolved minerals and increasing conductivity. The process can escalate: increased conductivity allows higher current, higher current generates more heat, heat concentrates minerals further increasing conductivity, until a catastrophic arc forms or protective devices operate.

Humidity affects insulation resistance even without visible moisture. In high humidity environments, water vapor adsorbs onto insulating surfaces, creating thin conductive films that degrade insulation resistance. This is why electrical equipment specifications often include maximum operating humidity limits and why equipment must be dried before energizing after storage in humid conditions.

Manufacturing Defects and Design Flaws

Sometimes short circuits result from defects present from manufacturing. A stray wire strand bridging circuit board traces, insulation that fails to fully cover a conductor, improperly crimped connectors that allow conductor strands to escape—all these manufacturing defects create short circuit risks that may not manifest until the product has been in service for some time.

Design flaws contribute to short circuit susceptibility. Insufficient spacing between conductors at different voltages, inadequate insulation thickness for operating voltage, poor strain relief allowing wires to flex and break, or failure to account for thermal expansion that causes conductors to move can all lead to eventual short circuits. Robust electrical design includes adequate safety margins to prevent these failure modes.

Component Failures

Electronic components can fail in ways that create short circuits. Capacitors can short internally when dielectric material breaks down. Transistors can short from collector to emitter when semiconductor junctions fail. Transformers can develop shorted turns when insulation between windings breaks down. Integrated circuits can short internally from electrostatic discharge damage or manufacturing defects that manifest after some operating time.

These component-level short circuits may initially be limited by the failed component’s internal resistance, but they often escalate. A partially shorted capacitor draws increasing current that generates heat, accelerating the failure until the capacitor shorts completely or explodes. Understanding that components can fail into short circuit conditions influences circuit design, leading to protective measures like current limiting and fusing for critical components.

The Dangers of Short Circuits

Short circuits present multiple hazards that can damage equipment, cause fires, and threaten human safety. Understanding these dangers motivates proper prevention and protection strategies.

Excessive Heat Generation

The most immediate danger from short circuits is extreme heat generation through resistive losses. Power dissipated in resistance equals current squared times resistance (P = I²R). When short circuit current increases by a factor of 100, power dissipation increases by a factor of 10,000 if resistance remains constant. This enormous power dissipation generates intense heat that can instantly vaporize conductors, ignite insulation, and start fires.

Even very low-resistance short circuits generate destructive heat because of the squared relationship between current and power. A short circuit with only 0.01 ohm resistance carrying 1,000 amps dissipates 10,000 watts of power (P = I²R = 1000² × 0.01 = 10,000W). This is equivalent to running ten 1,000-watt space heaters in a tiny location where the short circuit occurs. The temperature rise is nearly instantaneous and can easily exceed the ignition temperature of nearby combustible materials.

Conductors have specific current-carrying capacities based on their cross-sectional area and cooling conditions. Normal circuit design ensures conductors operate well below these limits. Short circuit currents can exceed conductor capacity by factors of hundreds or thousands, causing temperature rise that melts insulation within milliseconds, melts the conductor itself, or vaporizes the conductor creating an explosive expansion that can damage equipment and injure nearby personnel.

Fire Hazards

Electrical fires frequently originate from short circuits. The intense heat generated at the short circuit point ignites nearby combustible materials including wire insulation, building materials, furniture, and stored goods. Short circuit arcs produce temperatures exceeding 3,000°C, hot enough to ignite virtually anything nearby and hot enough to melt metals including copper and aluminum.

The sudden onset of short circuit heating makes these fires particularly dangerous. There is no gradual warming that might be detected by temperature sensors or noticed by occupants. A short circuit can progress from normal operation to full-involved fire in seconds, leaving little time for evacuation or fire suppression response.

Short circuit fires can be particularly difficult to extinguish because the electrical energy continues feeding the fire until power is interrupted. Water application to energized electrical fires creates shock hazards and can worsen the situation. Proper fire suppression requires first de-energizing the circuit, which may be difficult if the short circuit has damaged disconnecting means or protective devices.

Arc Flash and Arc Blast

When short circuits occur in systems with high available fault current, the energy released can create arc flash and arc blast events that are immediately lethal to nearby workers. An arc flash produces intense thermal radiation that can cause severe burns at distances of several feet from the arc. The ultraviolet radiation from the arc can cause eye damage similar to welding arc exposure but more severe due to higher intensity.

Arc blast refers to the explosive pressure wave created when vaporized conductor material rapidly expands. This pressure wave can throw workers across rooms, rupture eardrums, cause traumatic injuries, and propel molten metal and equipment fragments at high velocities. Arc blast pressures can exceed 2,000 pounds per square foot, more than sufficient to knock down walls and collapse equipment.

The energy in an arc flash/blast increases with voltage, available fault current, and arc duration. Industrial systems operating at 480 volts or higher with high available fault current require special precautions including arc flash hazard analysis, appropriate personal protective equipment, and work practices that minimize exposure to potential arc flash locations.

Equipment Damage

Short circuits damage electrical equipment through multiple mechanisms. The mechanical forces from short circuit current can warp bus bars, break conductor connections, and cause structural deformation of electrical equipment. Magnetic fields from short circuit current create forces between parallel conductors that can be thousands of pounds, causing physical damage to busbars, cables, and equipment.

The intense heat from short circuits can destroy insulation systems, melt conductor connections, and damage semiconductor junctions. Even if a device survives the short circuit event, the thermal stress may have degraded components sufficiently that premature failure occurs later. This hidden damage makes equipment that has experienced short circuits unreliable even if it appears to function normally afterward.

Voltage sags during short circuits can damage sensitive electronic equipment throughout the affected electrical system, not just at the short circuit location. When a short circuit draws massive current, voltage collapses throughout the system due to voltage drop in source impedance and distribution conductors. This voltage sag can cause computers to crash, industrial processes to trip offline, and adjustable speed drives to fault, creating widespread disruption from a localized short circuit.

Electrical Shock Hazards

While the short circuit itself typically occurs between conductors at different voltage levels rather than involving humans directly, short circuits create secondary shock hazards. Damaged insulation from short circuit heating exposes normally insulated conductors. Conductive debris scattered by arc blast may create new paths for current flow. Damaged equipment enclosures may become energized at dangerous voltages.

First responders and maintenance personnel face particular shock risks when approaching equipment involved in short circuits. Metal enclosures may be energized. Conductors assumed to be de-energized may still be live due to backfeed or damaged isolation. Wet conditions from fire suppression efforts increase shock risk. Proper lockout/tagout procedures and voltage verification before touching equipment are essential after short circuit events.

Short Circuit Protection Devices

Electrical systems incorporate multiple protection devices specifically designed to detect and interrupt short circuits before they cause catastrophic damage. Understanding these protective devices helps you appreciate how electrical systems achieve safety despite the ever-present short circuit risk.

Fuses: The Sacrificial Protector

Fuses protect circuits by providing a deliberately weak link that melts and opens the circuit when excessive current flows. The fuse element consists of a conductor sized to melt at a specific current level, interrupting current flow before downstream conductors or equipment sustain damage.

Fast-acting fuses melt within milliseconds of experiencing overcurrent, providing rapid protection for sensitive electronic equipment. Slow-blow or time-delay fuses tolerate brief overcurrent surges that occur during motor starting or capacitor charging, melting only if sustained overcurrent continues for enough time to generate destructive heat. This discrimination between brief acceptable surges and sustained dangerous overcurrent makes fuses versatile protection devices.

When a fuse operates during a short circuit, it must safely interrupt fault current that may be many times its rating. High-quality fuses include arc-quenching materials like sand that absorb energy from the arc created when the fuse element vaporizes, preventing arc-over that would allow current to continue flowing despite the melted element. Fuse voltage ratings specify the maximum voltage the fuse can safely interrupt, and exceeding this rating can cause explosive fuse failure.

Fuse replacement after operation requires selecting the correct current rating, voltage rating, and response characteristic. Using incorrect fuses creates either inadequate protection (fuse rating too high) or nuisance operations (fuse rating too low). The fuse should protect the circuit conductors and loads while allowing normal operating currents and tolerable transient overcurrents.

Circuit Breakers: The Reusable Protector

Circuit breakers perform the same basic function as fuses—interrupting excessive current—but can be reset and reused after operation. This reusability makes breakers more economical than fuses for applications involving frequent overcurrent events, though quality circuit breakers cost significantly more than comparable fuses.

Thermal-magnetic circuit breakers, the most common type in residential and light commercial applications, use two separate mechanisms to detect overcurrent. The thermal element consists of a bimetallic strip that heats and bends when carrying current. Sustained moderate overcurrent from overloads causes the strip to bend enough to trip the breaker mechanism after a time delay proportional to overcurrent magnitude. This provides protection against overload conditions.

The magnetic element provides instantaneous response to very high currents characteristic of short circuits. When short circuit current flows through the breaker, it creates a strong magnetic field that pulls an armature that mechanically trips the breaker. This magnetic trip operates within one cycle or less, providing rapid short circuit protection.

Electronic circuit breakers use current sensors and microprocessor control to provide sophisticated protection characteristics. These breakers can implement precise time-current curves, ground fault detection, arc fault detection, and communication capabilities. While more expensive than thermal-magnetic breakers, electronic breakers provide advanced protection features for critical applications.

Circuit breaker interrupt rating specifies the maximum short circuit current the breaker can safely interrupt. This rating must exceed the available fault current at the installation location, or the breaker may explode when attempting to interrupt a short circuit. Proper circuit breaker application requires calculating available fault current and selecting breakers with adequate interrupt ratings.

Ground Fault Protection

Ground fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) detect current flowing through unintended ground paths, including through humans touching energized conductors. A GFCI monitors current in the hot and neutral conductors. In normal operation, these currents are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction. When current flows through a ground path, the hot current exceeds the neutral current. The GFCI detects this imbalance and trips within milliseconds, interrupting the circuit before lethal current can flow through a human.

GFCIs provide essential protection in locations where water contact creates shock hazards: bathrooms, kitchens, outdoor outlets, and construction sites. Modern electrical codes require GFCI protection in these locations because the rapid response time prevents electrocution that could occur before a standard circuit breaker trips.

Arc fault circuit interrupters (AFCIs) detect arcing conditions that can cause fires but may not draw enough current to trip standard circuit breakers. These devices monitor current waveforms for the characteristic rapid fluctuations caused by arcing and interrupt the circuit when dangerous arcing is detected. AFCIs prevent fires from damaged cords, loose connections, and other faults that create intermittent arcing without drawing short circuit current levels.

Coordination and Selectivity

In systems with multiple levels of protection, coordination ensures that the protective device closest to a fault operates first, minimizing the extent of system shutdown. If a short circuit occurs in one branch circuit, ideally only that branch’s breaker should trip rather than the main breaker interrupting power to the entire building.

Achieving coordination requires selecting protective devices with compatible time-current characteristics. The upstream device must have slower response at the fault current level than the downstream device, allowing the downstream device time to clear the fault before the upstream device trips. This becomes increasingly difficult with high fault currents where all protective devices tend to operate very rapidly.

Selective coordination is particularly important for critical systems like hospitals, data centers, and life safety systems where unnecessary interruptions can have serious consequences. These installations use sophisticated protection schemes with current-limiting fuses, electronic trip circuit breakers, and careful coordination analysis to ensure maximum selectivity.

Preventing Short Circuits

While protective devices limit short circuit damage, prevention is always preferable to protection. Multiple strategies reduce short circuit likelihood through design, installation, and maintenance practices.

Proper Circuit Design

Good circuit design incorporates short circuit prevention from the beginning. Adequate spacing between conductors at different voltages prevents accidental contact. Insulation rated for operating voltage plus safety margin prevents breakdown even under abnormal conditions. Strain relief prevents wire flexing that can damage insulation. Proper component selection ensures devices are not operated near their voltage or current limits where failure becomes more likely.

Current limiting in circuit design prevents short circuits in some loads from propagating to power sources. Adding series resistance, inductance, or active current limiting reduces fault current that could occur if the load shorts. This protection is particularly important for battery-powered equipment where the battery could deliver destructive current to a shorted load.

Conformal coating or potting of circuit boards protects against conductive contamination and moisture that could create short circuits. The coating creates an insulating barrier over conductors and components, preventing bridges from conductive debris or moisture films. This protection is essential for harsh environments but adds cost and makes repair more difficult.

Quality Installation Practices

Even well-designed equipment can experience short circuits from improper installation. Properly stripping wire insulation ensures insulation extends to connection points without leaving conductors exposed. Correct torque on terminal connections prevents loose connections that can generate heat and fail. Maintaining proper bend radius prevents insulation stress cracking. These basic installation practices dramatically reduce short circuit risks.

Cable routing that avoids sharp edges, prevents crossing of hot surfaces, and provides adequate support prevents mechanical damage that can lead to short circuits. Separate routing of power and signal cables prevents inductive coupling and reduces arc-over risk. Proper use of grommets and bushings where cables penetrate metal enclosures prevents insulation abrasion.

Using appropriate connectors and terminals for the application ensures reliable connections that will not work loose due to vibration or thermal cycling. Crimped connections must use correct crimp tools and techniques to ensure reliable contact. Soldered connections require proper surface preparation and solder application to achieve mechanical and electrical integrity.

Regular Maintenance and Inspection

Electrical systems require periodic inspection to identify developing problems before they escalate to short circuits. Visual inspection can reveal damaged insulation, loose connections, signs of overheating, corrosion, moisture infiltration, and physical damage. Thermographic inspection detects hot spots from loose connections or overloaded conductors before they fail catastrophically.

Insulation resistance testing measures insulation quality, revealing degradation before complete breakdown occurs. This testing applies high voltage (500-5,000 volts depending on system voltage) and measures leakage current through insulation. Decreasing insulation resistance over time indicates degradation requiring investigation. Values below minimum acceptable levels require corrective action before energizing equipment.

Connection tightness checking ensures all screw terminals, lugs, and mechanical connections maintain proper contact pressure. Vibration, thermal cycling, and corrosion can loosen connections over time. Regular retightening following manufacturer specifications prevents high-resistance connections that lead to overheating and eventual failure.

Environmental control in electrical equipment rooms prevents moisture infiltration and condensation that degrade insulation. Maintaining proper temperature and humidity ranges, preventing water intrusion, and ventilating equipment adequately all extend insulation life and reduce short circuit risk.

Protection From Physical Damage

Conduit and cable trays provide mechanical protection for conductors, preventing impact damage, abrasion, and contamination exposure. Properly installed conduit systems protect against nail penetration, crushing, and other mechanical hazards. The additional cost of conduit is easily justified by the protection it provides and the reduced fire and shock hazards.

Equipment enclosures protect against foreign object intrusion, moisture ingress, and accidental contact with live conductors. NEMA and IP ratings specify protection levels against these hazards. Selecting appropriate enclosure ratings for the installation environment prevents many short circuit causes.

Proper labeling and barriers prevent accidental contact with energized conductors during maintenance. Live parts should be guarded or enclosed to prevent accidental contact. Where exposure is necessary for operation or maintenance, warning labels and barriers help prevent accidents.

Education and Training

Personnel working with electrical systems must understand short circuit hazards and prevention methods. Training should cover proper work practices, use of personal protective equipment, lockout/tagout procedures, and emergency response. Understanding why procedures exist promotes compliance better than simply mandating procedures without explanation.

Electrical safety training should be role-specific. Electricians need detailed knowledge of installation practices and electrical codes. Operators need to understand how to recognize abnormal conditions and when to shut down equipment. Maintenance personnel need to understand testing procedures and precautions. Management needs to understand resource requirements for maintaining electrical safety.

Responding to Short Circuits

When short circuits occur despite prevention efforts, proper response limits damage and restores safe conditions.

Immediate Actions

If you witness a short circuit event with arcing or fire, immediately evacuate the area and call emergency services. Do not attempt to fight electrical fires with water. If safe to do so and you know the location of the disconnecting means, de-energize the circuit. Never approach damaged electrical equipment until confirmed de-energized by qualified personnel.

If a circuit breaker trips or fuse blows, do not immediately reset the breaker or replace the fuse. The protective device operated for a reason—either a short circuit or sustained overload. Investigate the cause before restoring power. Repeatedly resetting breakers or replacing fuses without addressing the underlying problem can cause fires or equipment damage.

Investigation and Repair

After a short circuit, investigate thoroughly to identify the root cause. Visual inspection may reveal obviously damaged components, burned insulation, or foreign objects. However, some short circuit causes are intermittent or not immediately visible. Insulation resistance testing can identify degraded insulation. Thermographic inspection after restoration of power can identify hot spots that indicate impending failures.

Repair of short circuit damage must address both the immediate damage and the root cause. Simply replacing damaged components without correcting the condition that caused the short circuit ensures recurrence. If insulation degradation caused the short circuit, replacing the component with identical material may simply delay the next failure. Understanding failure modes guides effective repairs.

Documentation of short circuit events helps identify patterns and common causes. Recording location, time, weather conditions, circuit loads, and other factors may reveal correlations that guide preventive measures. Repeated short circuits in particular locations or under particular conditions indicate systemic problems requiring comprehensive solutions.

When to Call Professionals

Some short circuit situations absolutely require professional electrical contractors or technicians. If the short circuit involved high voltage equipment, extensive damage, fire, or injury, professionals must evaluate and repair the system. If you do not understand the electrical system or cannot identify the cause, professionals should investigate. If insulation resistance testing or other diagnostic procedures are needed, specialized equipment and training are required.

Even if you have the knowledge to address a short circuit, local electrical codes may require licensed electricians perform certain work. Permit and inspection requirements exist to ensure electrical work meets safety standards. Attempting electrical work beyond your knowledge and legal authorization creates liability and safety risks.

Conclusion: Respecting Electrical Power

Short circuits represent one of the most dangerous fault conditions in electrical systems, capable of causing fires, explosions, severe equipment damage, and fatal injuries within milliseconds of occurrence. They occur when unintended low-resistance paths bypass normal circuit components, allowing currents hundreds or thousands of times greater than normal operating levels to flow. This extreme current generates intense heat, creates arc flash hazards, damages equipment, and can quickly escalate to catastrophic failure.

Understanding short circuits requires grasping how Ohm’s Law governs current flow, recognizing the multiple mechanisms that create unintended connections between voltage levels, appreciating the time scales on which short circuit damage occurs, and implementing multiple layers of protection and prevention. No single measure completely prevents short circuits, but comprehensive approaches combining good design, quality installation, regular maintenance, and appropriate protective devices reduce risks to acceptable levels.

Protective devices including fuses, circuit breakers, ground fault interrupters, and arc fault interrupters detect and interrupt short circuits before catastrophic damage occurs. These devices must be properly selected, installed, and maintained to provide reliable protection. Understanding their operation and limitations helps you design and maintain electrical systems that fail safely when faults occur.

Prevention remains superior to protection. Proper circuit design with adequate insulation, spacing, and current limiting prevents many short circuits from occurring. Quality installation practices ensure connections remain secure and insulation remains intact. Regular inspection and maintenance identify degradation before it progresses to failure. Environmental control prevents moisture and contamination that cause insulation breakdown.

The electrical systems powering modern civilization are remarkably safe considering the enormous energies they control and distribute. This safety results from over a century of evolution in protective devices, installation practices, electrical codes, and safety standards—all developed in response to short circuit failures and other electrical hazards. Understanding short circuits and their prevention gives you the knowledge to work safely with electrical systems, whether you are designing circuits, installing equipment, performing maintenance, or simply using electrical devices in daily life.

Respect for electrical power, manifested in proper design, installation, maintenance, and operating practices, keeps short circuits rare and their consequences manageable. This respect, combined with knowledge of how short circuits occur and how to prevent them, enables you to work safely and confidently with electrical systems of all types and sizes. As you continue your electronics journey, carry this understanding forward, applying it to every circuit you design, every installation you perform, and every piece of electrical equipment you use.