Introduction

Measuring current differs fundamentally from measuring voltage in ways that make current measurement simultaneously more challenging and more hazardous for beginners, requiring the meter to be inserted in series with the current path rather than simply touching probes to existing circuit points, demanding careful attention to expected current magnitudes to select appropriate meter ranges and avoid damage, and creating potential for blown fuses or damaged meters if measurement procedures are performed incorrectly. Despite these additional complexities and hazards, current measurement provides essential diagnostic information about circuit operation that voltage and resistance measurements cannot reveal, including whether circuits draw expected current from power supplies, verifying that current-limiting resistors actually limit current to safe values, identifying short circuits that draw excessive current, and confirming that components receive adequate current to operate while not exceeding their maximum ratings. Understanding how to measure current safely and correctly transforms this potentially intimidating measurement into a routine diagnostic tool supporting circuit verification and troubleshooting.

For beginners approaching current measurement for the first time, the requirement to break circuits and insert the meter in series creates uncertainty and anxiety that does not accompany voltage measurement where probes simply touch existing circuit points without requiring circuit modification. The invasive nature of current measurement means you must disconnect a component lead from a breadboard or cut a wire to create an insertion point, connect meter probes to the two sides of this break to complete the circuit through the meter’s current sensing circuit, then reconnect the circuit after measurement completes. This process feels destructive and risky compared to the non-invasive voltage measurement, motivating careful planning of where to insert the meter to minimize circuit disruption while still obtaining needed measurements.

The hazard of damaging multimeters through improper current measurement arises because meters set to current mode present very low resistance—often less than one ohm—allowing them to carry substantial current without significantly affecting circuit operation but also making them vulnerable to damage if accidentally connected across voltage sources creating short circuits that drive currents far exceeding meter ratings. A multimeter set to measure current and accidentally connected across a twelve-volt battery would attempt to pass twelve volts through one ohm or less of resistance, producing twelve amperes or more that would instantly blow the protective fuse in most multimeters and potentially damage the meter if current exceeds even the fuse rating. This danger makes verifying meter settings and understanding circuit conditions before connecting probes absolutely critical for current measurement in ways that are less critical for voltage measurement.

The practical value of current measurement extends throughout electronics work from initial design verification confirming calculations match reality, through assembly checking that components draw expected currents, to troubleshooting identifying short circuits, open circuits, or component failures that manifest as abnormal current consumption. A circuit that should draw fifty milliamps but actually draws five hundred milliamps clearly has problems requiring investigation, while a circuit drawing essentially zero current despite being powered indicates an open circuit preventing current flow. These diagnostic insights come only from current measurement, making the skill essential despite its additional complexity compared to voltage measurement.

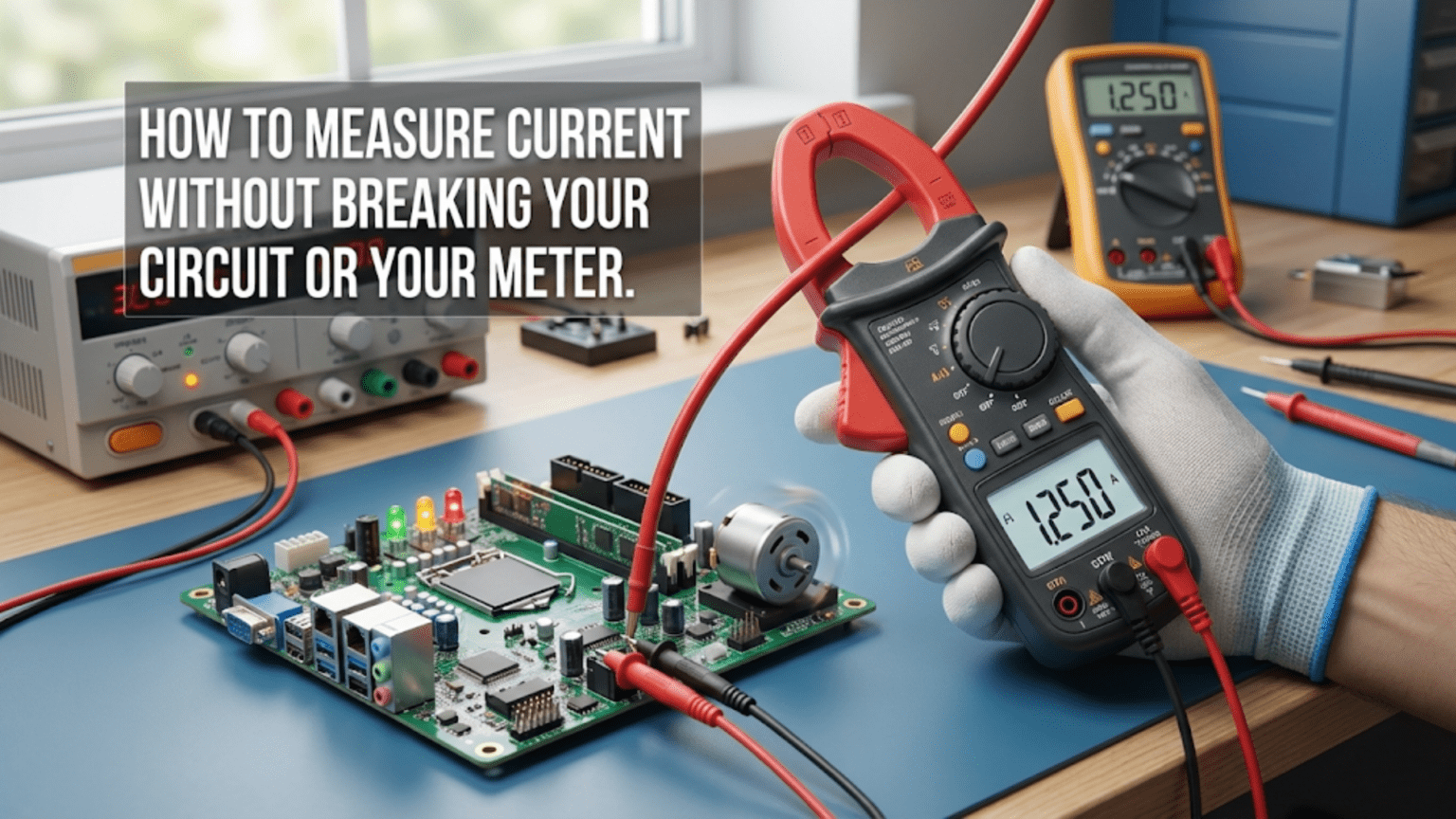

This comprehensive guide will build your current measurement skills from fundamental concepts through safe practical procedures, examining why current measurement requires series insertion rather than parallel connection, how to select appropriate meter ranges and input jacks for expected current levels, detailed step-by-step procedures for safely measuring current in DC circuits, understanding meter fuse protection and what to do when fuses blow, common mistakes that damage meters or circuits and how to avoid them, interpreting current measurements to diagnose circuit behavior, and advanced current measurement techniques including AC current and clamp meter alternatives. By the end, you will understand current measurement thoroughly enough to confidently measure current when needed while avoiding the common mistakes that damage equipment or produce incorrect readings.

Why Current Measurement Requires Series Connection

Understanding the fundamental difference between voltage and current measurement—parallel versus series connection—clarifies why current measurement procedures differ from voltage measurement and why correct insertion is critical.

The Nature of Current Flow

Current represents the rate of charge flow through a circuit, measured at a specific point in the current path rather than between two points as voltage is measured. To measure how much current flows through a component or circuit section, the measurement instrument must be placed in that current path so the current being measured actually flows through the instrument’s current sensing circuit. This requirement for current to flow through the meter means the meter must be inserted in series with the circuit, becoming part of the current path rather than merely observing from the sidelines as voltage measurement does.

The water flow analogy helps visualize this series requirement. Measuring water flow rate through a pipe requires inserting a flow meter into the pipe so all water passes through the meter as it flows, enabling the meter to count or sense the flow. Similarly, measuring electrical current requires inserting the ammeter into the circuit so all electrons flowing through that circuit point also flow through the meter enabling current sensing. Just as you cannot measure water flow by holding a flow meter near a pipe without actually routing water through it, you cannot measure electrical current by merely touching probes to a circuit without routing current through the meter.

This series connection requirement explains why current measurement is more invasive than voltage measurement. Voltage measurements connect in parallel, touching existing circuit points without modifying circuit topology or interrupting normal operation. Current measurements require breaking the circuit at the measurement point and inserting the meter to complete the circuit through the meter’s current path, fundamentally altering circuit connectivity during measurement. After measurement, the circuit must be reconnected to its original configuration restoring normal operation.

Why Low Meter Resistance Matters

For current measurements to avoid significantly affecting the current being measured, the meter must present very low resistance in the current path—ideally zero resistance though practical meters have small but non-zero resistance typically less than one ohm. This low resistance ensures that inserting the meter in series adds minimal voltage drop and thus minimal effect on circuit current compared to the circuit without the meter present. A meter with zero point one ohm resistance inserted in a circuit section with ten ohms total resistance adds only one percent additional resistance, changing current by approximately one percent which is negligible for most purposes.

However, this low resistance that makes meters transparent to normal circuit operation becomes a hazard when meters are accidentally connected incorrectly. If a meter set to current mode is connected across a voltage source rather than in series with a current path, the low meter resistance creates a short circuit allowing the voltage source to drive enormous current through the meter. A twelve-volt battery connected across one ohm of meter resistance produces twelve amperes of current that will instantly blow protective fuses and potentially damage the meter if current exceeds fuse ratings. This is exactly what happens when someone leaves the meter set to current mode after completing a current measurement, then attempts to measure voltage—the voltage connection across the meter’s low-resistance current path creates a short circuit.

This fundamental hazard explains why current measurement requires heightened awareness and careful verification of meter settings before connecting to circuits. While voltage measurement mode presents high impedance that draws negligible current and tolerates connection across any reasonable circuit voltage without damage, current measurement mode presents low impedance that creates short circuits when connected across voltage sources. The consequences of mixing up these modes are asymmetric—measuring current with the meter set to voltage mode simply yields no reading because the high impedance blocks current flow, but measuring voltage with the meter set to current mode blows fuses or damages meters.

Planning Series Insertion Points

Before measuring current, identify where in the circuit you want to measure current flow and plan where to break the circuit for meter insertion. For simple series circuits, any break in the series path allows measuring total circuit current. For circuits with parallel branches, breaking different locations measures different branch currents or total current depending on whether you break before or after parallel branches divide current. Understanding circuit topology and current flow paths ensures you measure at locations that provide the diagnostic information you need.

Common current measurement points include the power supply output measuring total circuit current consumption, individual component current measuring how much current flows through specific components, and branch currents in parallel circuits measuring how current divides among branches. In breadboard circuits, disconnecting a component lead or jumper wire creates a convenient insertion point where meter probes easily connect to the component lead and the breadboard hole from which it was removed. In soldered circuits, test points or jumpers designed for current measurement simplify insertion, while circuits without such provisions might require cutting traces or wires to create insertion points.

Setting Up Your Multimeter for Current Measurement

Proper meter configuration protects the meter from damage while enabling accurate current measurement.

Selecting Current Function and Range

Set the multimeter selector dial to the appropriate current function—DC current for measuring DC circuits or AC current for measuring AC power consumption. DC current mode measures steady current flow in battery-powered circuits and DC power supplies, while AC current mode measures alternating current in AC-powered devices. The selector typically indicates DC current with an A and straight or dashed lines, while AC current appears as an A with a sine wave symbol. Some meters label functions as “DCA” and “ACA” making the distinction obvious.

Critically important is selecting a current range appropriate for the expected current magnitude. Unlike voltage measurement where selecting too low a range merely causes overload indications without damage, selecting a current range too low for the measured current can blow protective fuses requiring fuse replacement before the meter functions again. If you expect to measure fifty milliamps, select a range rated for at least fifty milliamps and preferably higher for safety margin—perhaps two hundred milliamps if available. If you expect five amperes, you must use the high-current range typically rated for ten or twenty amperes.

Auto-ranging multimeters cannot auto-range current measurement across the full range from milliamps to multiple amperes because the different current ranges require different input jack connections as we will discuss next. Instead, auto-ranging typically applies within a selected current range—the milliamp range might auto-range from microamps through two hundred milliamps, while the high-current range might auto-range from hundreds of milliamps through ten amperes. You still must manually select between milliamp and high-current ranges through jack connections, but the meter automatically optimizes within the selected range.

Moving Test Probes to Current Input Jacks

This step is absolutely critical and is where most current measurement mistakes occur. The red test probe must move from the voltage measurement jack to the appropriate current measurement jack based on expected current magnitude. Most multimeters provide two current jacks—a milliamp jack typically rated for two hundred or four hundred milliamps protected by a small fuse, and a high-current jack typically rated for ten or twenty amperes that may be unfused or protected by a very high-rated fuse.

For measuring currents below two hundred milliamps, move the red probe to the milliamp jack often labeled “mA” or “200mA” depending on its rating. This jack connects to current sensing circuitry protected by a fuse that blows if current exceeds the rated value, protecting the meter from damage at the cost of requiring fuse replacement if you accidentally exceed the rating. For measuring currents above two hundred milliamps or when you are uncertain about current magnitude and want maximum protection, move the red probe to the high-current jack labeled “A” or “10A” depending on rating.

The black probe remains in the COM or common jack for current measurement just as for voltage measurement. Only the red probe moves between voltage, milliamp current, and high-current jacks depending on the measurement being performed. This asymmetry where only the red probe moves simplifies the procedure somewhat, but creates a critical point of failure if you forget to move the red probe from current jacks back to the voltage jack when switching from current to voltage measurement.

Developing a habit of always verifying red probe jack position before connecting to circuits prevents the common mistake of measuring voltage with the probe still in the current jack from a previous measurement. Some practitioners make it standard practice to move the red probe back to the voltage jack immediately after completing each current measurement, ensuring the meter defaults to the safer voltage measurement configuration rather than remaining in the hazardous current measurement configuration. This practice prevents damage from accidentally connecting to circuits while the meter is still configured for current measurement.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Measuring DC Current

Following systematic procedures ensures safe accurate current measurements while minimizing risks to the meter and the circuit being measured.

Step 1: Estimate Expected Current

Before measuring current, estimate the approximate current magnitude you expect to measure based on circuit voltage and total resistance, or based on component specifications if you are measuring current through a specific component. For example, in a nine-volt circuit with a total resistance of one kilohm, expected current equals nine volts divided by one kilohm equals nine milliamps. For an LED circuit with twelve volts, a two-volt LED drop, and a five-hundred-ohm current-limiting resistor, expected current equals ten volts divided by five hundred ohms equals twenty milliamps.

This estimation serves multiple critical purposes. First, it tells you whether to use the milliamp range or the high-current range, preventing damage from attempting to measure high currents through the low-current input that would blow fuses. Second, it provides a sanity check for your measurement—if you estimate twenty milliamps but measure two hundred milliamps, something is wrong either with your estimate, your measurement, or your circuit. Third, it verifies that current measurement is actually safe and appropriate—if you calculate expected current of ten amperes but your meter only handles two hundred milliamps maximum, you cannot safely measure this current with that meter.

If you cannot estimate expected current because circuit complexity prevents easy calculation, default to the high-current range and meter input for initial measurement, accepting reduced resolution in exchange for safety. Once you determine approximate current magnitude from this initial measurement, you can switch to the milliamp range if current is low enough to benefit from improved resolution, or remain on the high-current range if current approaches or exceeds the milliamp range rating.

Step 2: Configure the Multimeter

Set the selector dial to DC current mode indicated by the A symbol with straight or dashed lines or the “DCA” label. Based on your current estimate from Step 1, select the appropriate current range if using a manual ranging meter. If expected current is below two hundred milliamps, select a milliamp range. If expected current exceeds two hundred milliamps or is uncertain, select the high-current range.

Move the red test probe to the appropriate current input jack matching your range selection—the milliamp jack for currents below two hundred milliamps, or the high-current jack for larger currents. Verify that the black probe remains in the COM jack. Take a moment to consciously verify that the selector dial shows current mode, not voltage mode, and that the red probe is in a current jack, not the voltage jack. This verification prevents measuring current with the meter still set to voltage mode which would yield no reading, and prevents the much more serious error of measuring voltage with the meter set to current mode which would create a short circuit.

Step 3: Power Off Circuit and Create Insertion Point

Before physically inserting the meter, power off the circuit by disconnecting the battery, turning off the power supply, or otherwise ensuring no current will flow when you break the circuit. This power-off requirement prevents current from flowing through circuit wiring during the circuit breaking process and prevents unexpected behavior as the circuit is interrupted. Some circuits might be damaged or behave unpredictably if power is removed, but this is generally preferable to the risks of modifying circuits while powered.

Break the circuit at the planned measurement point by disconnecting a component lead from the breadboard, removing a jumper wire, or in soldered circuits perhaps removing a component entirely or cutting a trace depending on how the measurement point was designed. The break creates two connection points—the component lead or wire end on one side, and the breadboard hole or circuit connection point on the other side. These two points will connect to the meter probes, with current flowing from one probe through the meter’s current sensing circuit to the other probe, completing the circuit through the meter.

Step 4: Connect Meter in Series

Connect the black meter probe to one side of the circuit break—typically the side closer to ground or the negative power supply terminal, though for DC current measurement the direction does not affect current magnitude and only affects whether the display shows positive or negative values. Connect the red probe to the other side of the break, completing the circuit through the meter. Current will flow from one side of the break, through the meter’s current sensing circuit, to the other side.

For example, if measuring LED current by removing the LED from the breadboard, the LED anode lead might have previously connected to a breadboard row connected to the positive power rail through a current-limiting resistor. After removing the LED, connect the black probe to the cathode and the red probe to that breadboard row where the anode was connected. Current flows from the power rail through the resistor, through the red probe, through the meter, through the black probe, through the LED, back to ground.

Verify that both probes make solid contact with their connection points, with the circuit now completed through the meter rather than through the original component or wire that was removed. The circuit should be complete through the meter with no open circuits remaining—if the circuit is still open, no current will flow and the meter will read zero regardless of whether the circuit would normally conduct current.

Step 5: Power On and Read Current

Apply power to the circuit by reconnecting the battery, turning on the power supply, or otherwise restoring power. Current flows through the circuit including through the meter, with the meter displaying the measured current value. Read the display noting whether the value is positive or negative, the magnitude, and the units which might be microamps, milliamps, or amperes depending on the range and measured value.

Compare the measured current to your estimate from Step 1. If values are reasonably close—within perhaps twenty or thirty percent accounting for component tolerances and estimation errors—the measurement likely reflects actual circuit operation. If measured current differs dramatically from estimates—perhaps ten times higher or lower—either the estimate was wrong, the circuit is not operating as expected, or the measurement is incorrect due to poor connections or meter setting errors. Investigate significant discrepancies to identify whether problems lie in estimation, circuit operation, or measurement procedure.

Watch for blown fuse indications on some meters if measured current exceeds the fuse rating. Symptoms of blown fuses include the meter showing zero current despite power being applied and circuit appearing to be complete, or the meter displaying an error code or message indicating protection activation. If a fuse blows, the meter cannot measure current until the fuse is replaced, though other meter functions like voltage and resistance measurement typically continue working using separate circuits.

Step 6: Power Off and Reconnect Circuit

After reading the current measurement, power off the circuit before removing the meter. Disconnecting the meter while power is applied opens the circuit potentially creating voltage spikes from inductive loads or leaving the circuit in an unexpected state. Powering off before disconnecting ensures clean meter removal without disturbing circuit operation.

Remove the meter probes from the circuit break points and reconnect the circuit to its original configuration by reinserting the component lead that was removed, replacing the jumper wire, or otherwise restoring the connection that was broken to insert the meter. Verify that the circuit is correctly reconnected before applying power for normal operation. Move the red probe back to the voltage jack if you are finished measuring current, preventing accidental voltage measurement while the probe remains in a current jack.

Understanding and Replacing Blown Fuses

Multimeter fuses protect the meter from overcurrent damage but require replacement when they blow from excessive current, making fuse replacement an essential multimeter maintenance skill.

Why Fuses Blow and What Happens

The milliamp current input on most multimeters includes a fuse rated for two hundred or four hundred milliamps that blows when current exceeds this rating, opening the current measurement circuit and preventing current flow that would damage the meter’s current sensing resistor. Fuses blow either from attempting to measure current exceeding the range rating, or from accidentally creating short circuits by measuring voltage while the meter is set to current mode. The fuse sacrifices itself to protect the more expensive and difficult to replace current sensing circuit.

When a fuse blows, current measurement through that input stops functioning with the meter displaying zero current or an error indication even when current should be flowing. Other meter functions including voltage and resistance measurement continue working normally because they use separate circuits not protected by the milliamp fuse. This selective failure where current measurement fails but other functions work indicates blown fuse as the likely cause.

The high-current input may be unfused on some meters, or may have a fuse rated for ten or twenty amperes on others. Unfused high-current inputs can be damaged if current far exceeds the meter rating, while fused inputs provide protection at the cost of requiring fuse replacement if the high-current fuse blows. Some meters use ceramic fuses for high current inputs that can withstand the energy of interrupting large fault currents, while the milliamp input uses smaller glass fuses adequate for lower energy interruption.

Accessing and Replacing Fuses

Multimeter fuse access typically requires removing the battery cover on the back of the meter or opening the entire meter case by removing several screws. The fuse appears as a small glass or ceramic cylinder with metal caps on each end, held in spring clips or fuse holders. Some meters provide accessible fuse holders allowing fuse replacement without opening the case fully, while others require complete case opening to reach internal fuses.

To replace a blown fuse, verify replacement fuse specifications match the original fuse ratings which are marked on the fuse body and specified in the meter manual or printed on labels inside the meter case. Fuse ratings include current rating in amperes, voltage rating in volts indicating maximum voltage the fuse can safely interrupt, and often a speed rating like fast-blow or slow-blow indicating how quickly the fuse responds to overcurrent. Replacement fuses must match all these specifications to provide proper protection without nuisance blowing or inadequate protection.

Remove the blown fuse by pulling it from spring clips or unscrewing fuse holder caps, then insert the replacement fuse ensuring good contact with holder clips or caps. Close the meter case and verify that current measurement functions again by measuring a small known current. If current measurement still fails after fuse replacement, either the replacement fuse is incorrect or defective, or damage occurred to meter circuits beyond what the fuse protected, requiring professional repair or meter replacement.

Common Current Measurement Mistakes

Understanding typical errors prevents damage to meters and circuits while ensuring measurement accuracy.

Measuring Voltage While Set to Current Mode

This represents the most common and destructive current measurement mistake, occurring when someone completes a current measurement then attempts to measure voltage without moving the probe back to the voltage jack or changing the selector dial from current to voltage mode. The low resistance of the current measurement circuit creates a short circuit across the voltage being measured, potentially blowing the fuse or damaging the meter if current exceeds protection limits.

Prevention requires developing habits of always verifying meter settings before connecting to circuits, and preferably moving the red probe back to the voltage jack immediately after completing each current measurement. Making voltage measurement the default meter state means that forgetting to change settings results in attempting current measurement while set to voltage mode which yields no reading but causes no damage, rather than attempting voltage measurement while set to current mode which blows fuses.

Exceeding Current Range Ratings

Attempting to measure current exceeding the meter’s current rating damages unprotected inputs or blows fuses on protected inputs. This commonly occurs when measuring current without estimating expected values first, selecting the milliamp range for convenience without verifying that circuit current stays below milliamp range limits. A circuit drawing five hundred milliamps measured on a two hundred milliamp range blows the fuse instantly.

Prevention requires always estimating expected current before measurement and selecting ranges with adequate margin above expected values. When uncertain about current magnitude, default to the high-current range even though resolution is poorer, accepting reduced precision in exchange for protection. After determining approximate current from the high-current measurement, switch to the milliamp range only if current is definitely below the milliamp range rating with comfortable margin.

Incorrect Series Connection

Connecting the meter across a component rather than in series with current flow attempts to measure current as if it were voltage, yielding incorrect results or no reading. Current measurement requires breaking the circuit and inserting the meter in the break, not merely touching existing circuit points. The low meter resistance in current mode means connecting across components creates short circuits around those components potentially damaging them or the circuit.

Proper current measurement requires identifying where current flows and inserting the meter into that current path. In series circuits, breaking anywhere in the series path allows measuring total current. In parallel circuits, breaking specific branches measures individual branch currents, while breaking the common path before parallel branches divide measures total current.

Conclusion: Mastering Safe Current Measurement

Current measurement provides essential diagnostic information about circuit operation that voltage and resistance measurements cannot reveal, but requires careful attention to procedures and settings to avoid damage to meters and circuits. Understanding why current measurement requires series insertion rather than parallel connection clarifies the fundamental difference between current measurement and voltage measurement, explaining why current measurement is more invasive and potentially hazardous. The requirement to insert the meter in the current path means breaking circuits, creating insertion points, and reconnecting after measurement completes.

Proper meter configuration including selecting appropriate current functions and ranges, moving the red probe to correct current input jacks, and verifying settings before connecting to circuits prevents the common mistakes that blow fuses or damage meters. Estimating expected current before measurement ensures range selection provides adequate capacity without attempting to force excessive current through inadequate inputs. Moving the red probe back to the voltage jack after completing current measurements prevents the dangerous error of attempting voltage measurement while still configured for current mode.

Understanding fuse protection and knowing how to replace blown fuses transforms fuse replacement from a frustrating mystery into routine maintenance that quickly restores meter functionality when overcurrent protection activates. Keeping spare fuses on hand enables immediate replacement rather than waiting for parts delivery when fuses blow during measurement activities.

The careful procedures required for current measurement become routine with practice, transitioning from uncertain unfamiliar activity requiring conscious attention to each step into automatic procedure performed confidently. The diagnostic value of current measurement justifies the additional complexity compared to voltage measurement, providing insights into circuit operation that enable verification during assembly and troubleshooting during fault diagnosis. Time invested mastering current measurement pays dividends throughout your electronics journey as current measurements complement voltage and resistance measurements providing complete diagnostic capability.