Soldering is the process of joining two metal surfaces—such as a component lead and a circuit board pad—by melting a low-melting-point metal alloy called solder around the joint, which flows into the gap and forms a strong, permanent, electrically conductive bond when it cools and solidifies. The fundamentals of good soldering involve using the right temperature (typically 315–370°C for lead-free solder), heating both surfaces simultaneously before applying solder, allowing solder to flow freely onto the joint rather than forcing it, and achieving a smooth shiny (for leaded) or slightly matte (for lead-free) surface finish that confirms a reliable electrical and mechanical connection.

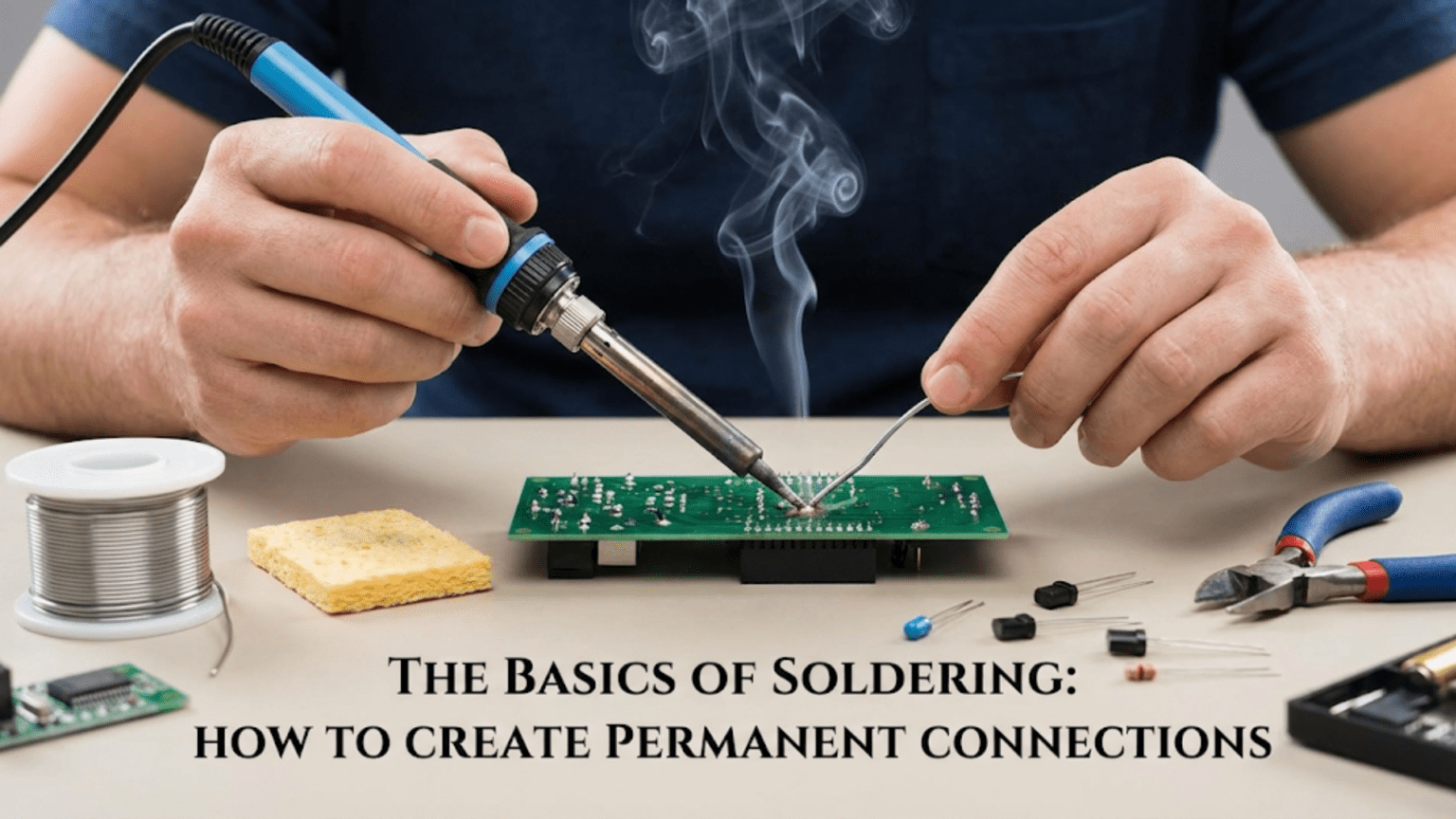

Introduction: The Skill That Connects the Electronics World

Every permanent electronic circuit ever built—from the first transistor radios to the latest smartphones, from hobbyist Arduino projects to sophisticated industrial control systems—relies on soldered connections. Soldering is the fundamental skill that transforms a collection of loose components into a functional, reliable circuit. It is the technique that gives electronics its permanence, turning breadboard experiments into real, lasting devices.

Despite its central importance, soldering intimidates many beginners. The idea of applying heat to delicate electronic components, working with molten metal, and somehow creating small, neat, reliable joints seems daunting when you’re first starting out. Yet soldering is fundamentally a simple physical process, and with the right equipment, understanding of the principles, and a little practice, virtually anyone can master it.

The good news is that soldering is a highly learnable skill. Unlike some crafts where innate talent plays a large role, good soldering technique is almost entirely a matter of understanding the underlying principles and then applying them consistently. Once you understand why solder flows the way it does, why temperature matters so much, and why both surfaces must be properly heated, creating good solder joints becomes intuitive rather than mysterious.

Beyond being a practical necessity, soldering is genuinely satisfying. There is real pleasure in heating a joint, watching solder flow smoothly and form a perfect bright fillet, and knowing you’ve created a connection that will last for decades. Skilled solderers take pride in their work—neat, consistent joints are a mark of craftsmanship in electronics, just as clean welds are in metalwork or tight joinery is in woodworking.

This comprehensive guide covers everything a beginner needs to start soldering confidently. We’ll explore the tools and materials you need, understand the science behind why solder works, learn proper technique step-by-step, work through different types of soldering tasks, understand what good and bad joints look like, and build the habits that separate competent solderers from those who struggle with cold joints, bridges, and lifted pads.

Whether you’re about to pick up a soldering iron for the first time or have been soldering for a while but want to improve your technique, this guide provides the foundation for creating reliable permanent connections throughout your electronics journey.

Understanding Solder: The Joining Metal

What Is Solder?

Solder is a metal alloy with a relatively low melting point that is used to join metal surfaces. In electronics, solder serves two purposes simultaneously: it creates a mechanical bond that holds components in place, and it creates an electrical connection that allows current to flow between the joined surfaces.

The most important property of solder is its ability to wet (spread across and adhere to) metal surfaces when molten. When solder wets properly, it flows into microscopic surface irregularities, creating intimate contact across the entire joint area. This wetting behavior is what distinguishes a good solder joint from a poor one—well-wetted solder forms smooth, flowing curves, while poorly wetted solder beads up or forms rough, lumpy surfaces.

Traditional Leaded Solder

For most of electronics history, the dominant solder formulation was 60/40 tin-lead (60% tin, 40% lead) or 63/37 tin-lead (63% tin, 37% lead, the eutectic composition).

Properties of 60/40 solder:

- Melting range: 183–190°C

- Solidification: Passes through a “pasty” state between fully liquid and solid

- Appearance when good: Bright, shiny, mirror-like surface

- Workability: Excellent—flows easily, wets readily, forgives technique errors

Properties of 63/37 eutectic solder:

- Melting point: Exactly 183°C (eutectic—no pasty state)

- Solidification: Transitions sharply from liquid to solid

- Advantages: Less prone to disturbed joint during cooling

- Preferred for precision work

Leaded solder is still widely used in repair, hobby electronics, and some professional applications where it remains legal. Its excellent working properties make it very beginner-friendly.

Lead-Free Solder

Due to environmental and health concerns, European RoHS (Restriction of Hazardous Substances) regulations and similar laws worldwide have made lead-free solder mandatory for most commercial electronics since 2006.

Common lead-free compositions:

- SAC305 (96.5% Sn, 3% Ag, 0.5% Cu): Industry standard, good reliability

- Sn96.5/Ag3.5: Two-component, slightly lower melting than SAC305

- SN100C (99.3% Sn, 0.7% Cu + small amounts of Ni and Ge): Good for wave soldering

Properties of lead-free solder (SAC305):

- Melting range: 217–220°C

- Working temperature: 350–400°C (higher than leaded)

- Appearance when good: Slightly matte, grainy appearance (normal—not a defect!)

- Workability: Less forgiving than leaded, requires better technique

Key difference for beginners: Lead-free solder is harder to work with. It requires higher temperature, doesn’t flow as easily, and wets less readily. Beginners often struggle with lead-free solder. If using leaded solder is legally and practically possible for your application, it provides a much easier learning experience.

Flux: The Essential Ingredient

Flux is a chemical cleaning agent that is critical to successful soldering. Without flux, clean solder joints are nearly impossible because metal surfaces oxidize instantly when heated, and oxide layers prevent solder from wetting.

What flux does:

- Chemically removes oxides from metal surfaces (component leads, PCB pads)

- Prevents re-oxidation during the soldering process

- Reduces surface tension of molten solder, improving flow and wetting

- Improves heat transfer to the joint

Types of flux:

- Rosin (R): Natural pine resin, mildly active, leaves non-corrosive residue

- Rosin mildly activated (RMA): More effective than plain rosin, widely used

- No-clean flux: Leaves residue that doesn’t need removal, popular in production

- Water-soluble flux: Very active, must be removed with water after soldering

Flux in solder wire: Most electronics solder wire has flux embedded in the core (called “flux-core solder”). The flux melts and activates as the solder melts, making it available where needed. This is the most convenient form for hand soldering.

Additional flux: For challenging joints, rework, or desoldering, applying additional flux with a flux pen or brush dramatically improves results. Many professional solderers add extra flux routinely.

Essential Soldering Equipment

The Soldering Iron

The soldering iron is your primary tool. Quality matters enormously—a poor iron makes good soldering nearly impossible.

Cheap irons (under $15–20):

- Fixed temperature, usually too cool or uncontrolled

- Slow recovery time (temperature drops when touching cold joints)

- Inconsistent temperature

- Short tip life

- Not recommended for beginners—these cause more problems than they solve

Temperature-controlled stations ($30–100 and up):

- Adjustable temperature with feedback control

- Fast thermal recovery

- Consistent temperature

- Wide tip variety available

- Strongly recommended: The best investment a beginning solderer can make

Popular beginner-friendly stations:

- Hakko FX-888D (industry standard entry-level)

- Weller WE1010NA

- Pinecil (USB-C powered, highly portable, excellent value)

- TS100 / TS80P (smart portable irons, popular with hobbyists)

Temperature settings:

- Leaded solder: 315–360°C (600–680°F)

- Lead-free solder: 350–400°C (660–750°F)

- Delicate components: Lower end of range

- Large pads/ground planes: Higher end (more thermal mass to heat)

Soldering Iron Tips

The tip is the business end of the iron and deserves careful attention.

Common tip shapes and their uses:

Conical (pointed) tips:

- Fine point for precision work, SMD components

- Lower heat transfer than chisel tips

- Slower to heat joints

Chisel (flat) tips:

- Flat face provides large contact area

- Excellent heat transfer

- Most versatile—good general-purpose choice

- Best starting tip for beginners

Bevel tips:

- Angled flat face

- Good thermal transfer

- Often preferred by professional solderers

Hoof/spoon tips:

- Curved surface holds a pool of solder

- Excellent for SMD drags soldering and rework

- Not for general through-hole work

Tip care: Good tip care dramatically extends tip life and maintains soldering quality:

- Keep the tip tinned (coated with fresh solder) whenever the iron is hot

- Clean regularly on brass wool tip cleaner (preferred) or damp sponge

- Never file or abrade the plated surface

- Apply fresh solder before storing the iron and before turning it off

- Replace tips that develop pits, holes, or won’t hold tin

Solder Wire

Wire diameter:

- 0.5–0.6mm: Fine pitch SMD work, delicate through-hole

- 0.7–0.8mm: General through-hole soldering, versatile

- 1.0mm+: Large connectors, heavy gauge wire, power connections

For beginners, 0.6mm or 0.8mm diameter flux-core solder is the most versatile choice.

Quantity: A 100g roll of solder wire lasts most hobbyists years of moderate use. Buying more than 250g at the start is unnecessary.

Other Essential Tools

Tip cleaner (brass wool): Brass wire mesh in a holder removes solder and contamination from the tip without cooling it significantly. Far superior to a wet sponge for tip longevity.

Soldering stand / holder: Safely holds the hot iron when not in use. Never set a hot iron down without a proper holder.

PCB holder / third hand: Holds PCBs or workpieces at convenient angles, freeing both hands for iron and solder.

Magnification: Even young people with excellent eyesight benefit from magnification for fine work. Options range from magnifying glasses to stereo microscopes. A 2–5× magnifier is very helpful.

Diagonal flush cutters: For trimming component leads after soldering. Get quality ones—cheap cutters dull quickly.

Desoldering tools:

- Desoldering pump (solder sucker): Spring-loaded vacuum removes molten solder

- Desoldering wick (braid): Copper braid wicks solder away by capillary action

Helping hands / PCB vise: Adjustable clips or vise to hold work steady. Absolutely essential—you cannot solder well while also holding the workpiece.

Safety essentials:

- Safety glasses: Solder spatter can fly; protect your eyes

- Fume extractor or ventilation: Solder flux fumes are irritating and potentially harmful with extended exposure

- Fire-safe surface: Soldering on a fireproof surface or heat mat

The Science Behind Good Solder Joints

Wetting: The Key to Solder Success

Wetting is the ability of liquid solder to spread across and adhere to a solid metal surface, forming a thin, continuous film. Good wetting is the hallmark of a good solder joint; poor wetting results in every type of soldering defect.

Wetting is governed by surface energy relationships and chemical bonding between the solder and base metals. When solder wets properly:

- It spreads across the surface rather than beading up

- It flows into gaps and between surfaces

- It forms smooth, concave meniscus curves when it solidifies

- It creates an intermetallic layer that bonds solder to base metal

What prevents wetting:

- Oxide layers: The primary enemy. Copper oxidizes instantly in air; tin, nickel, and other plated surfaces also oxidize.

- Contamination: Oils, fingerprints, flux residue from previous operations

- Insufficient temperature: Solder must be fully molten to wet properly

- Too little flux: Flux clears the way; without enough flux, oxides block wetting

How flux helps: Flux dissolves and removes oxide layers chemically, leaving clean metal surfaces that solder can wet. This is why freshly tinned or recently manufactured components solder easily while old, oxidized components require more flux and effort.

Heat Transfer and Thermal Mass

The fundamental rule: You must heat both surfaces being joined, not just the solder.

Many beginners make the mistake of melting solder with the iron and then depositing molten solder onto a cold joint. This produces a “cold joint”—solder that didn’t wet the surfaces properly, creating a poor electrical connection and weak mechanical bond.

Why both surfaces must be hot:

- Solder must be above its melting temperature to flow

- Cold surfaces immediately solidify any solder that touches them

- Flux only activates properly at temperature

- Wetting requires thermally assisted chemical reactions

Thermal mass consideration: Different parts of a circuit have different thermal masses—some heat quickly, others slowly:

- Small SMD pad: Heats in under a second

- Standard through-hole pad: Heats in 1–3 seconds

- Large ground plane connection: May take 5–10+ seconds

- Heavy gauge wire: Can require substantial iron dwell time

The iron tip must transfer enough heat to raise all parts of the joint to soldering temperature quickly—before flux burns away, before components overheat, and before surrounding parts are affected.

The Solder Joint Formation Process

When a good solder joint forms, several things happen in sequence:

- Iron contacts surfaces: Heat flows from tip into component lead and PCB pad

- Flux activates: As temperature rises, flux melts and chemically attacks oxide layers

- Surfaces reach temperature: Both lead and pad reach near-soldering temperature

- Solder is applied: Wire touches the junction of iron and joint (not the iron directly)

- Solder melts and flows: Molten solder wets the cleaned surfaces

- Iron is removed: Heat source removed

- Solder solidifies: Cools from outside in, forming solid intermetallic bonds

- Joint complete: Strong mechanical and electrical connection established

Critical: Don’t move during cooling! If the joint is disturbed while solder is in the pasty stage (partially solidified), the grain structure is disrupted, creating a “disturbed joint” with poor appearance and potentially poor reliability.

The Role of Intermetallic Compounds

Solder doesn’t just coat the metal surfaces—it chemically reacts with them to form intermetallic compounds (IMCs) at the interface. For copper pads (most common in PCBs) with tin-based solder, copper-tin IMC layers form.

These IMC layers:

- Are what actually creates the bond between solder and PCB

- Form quickly at soldering temperatures

- Grow thicker with time and temperature exposure

- Very thick IMCs become brittle—avoid overheating joints repeatedly

Practical implication: A good solder joint isn’t just physically stuck—it’s chemically bonded. This is why proper temperature and adequate dwell time matter: you need enough heat for the chemical reaction, but not so much that you damage components or grow excessively thick, brittle IMCs.

Core Soldering Technique: Step by Step

Before You Begin: Preparation

Good soldering starts before the iron is even plugged in.

Prepare your workspace:

- Clear adequate working space

- Ensure good lighting (bright, ideally from multiple angles)

- Have ventilation or fume extraction in place

- Set up PCB holder at comfortable working height

- Arrange components, solder wire, and tools within easy reach

- Put on safety glasses

Prepare components:

- Inspect leads for oxidation (dark, dull surface). Lightly abrade or tin if necessary.

- Bend component leads to fit holes before placing on board

- Place components in the correct orientation (polarity matters for diodes, LEDs, electrolytic capacitors)

- Ensure components sit flush to the board (unless design requires standoff)

Prepare the PCB:

- Clean with isopropyl alcohol if contaminated

- Check pad condition—good pads have shiny, flat surfaces

Heat up the iron:

- Set temperature: 340°C for leaded solder, 370°C for lead-free (adjust based on experience)

- Allow iron to reach full temperature (usually 1–3 minutes)

- Tin the tip: Apply fresh solder to the tip, then wipe on brass wool. Tip should be bright and shiny, covered with a thin solder film.

Step 1: Position and Stabilize

Good positioning prevents many problems:

Position the PCB: Hold or mount the PCB so the joint you’re working on is accessible with a comfortable wrist position. Awkward angles lead to poor results.

Stabilize components: Component leads that are sticking through the board may need temporary bending to hold the component in place. Some solderers use tape, component clips, or gravity (soldering top-side down) to hold parts.

Plan your approach: Look at the joint before touching it with the iron. Know where you’ll place the tip, where you’ll apply solder, and what the correct finished joint should look like.

Step 2: Apply the Iron

The iron contact point: Place the tip so it touches BOTH the component lead AND the PCB pad simultaneously. This is the fundamental technique—heating both surfaces at once.

For a through-hole component:

- Place the iron so the flat of the chisel tip contacts the pad on the board

- The tip simultaneously contacts the vertical component lead

- The tip is typically at a 45° angle to the board

Dwell time: Hold the iron in contact for 1–3 seconds before applying solder. This allows both surfaces to heat to soldering temperature.

Don’t press hard: The iron transfers heat through contact, not pressure. Pressing hard doesn’t help and can damage pads.

Step 3: Apply Solder

Where to apply solder: Feed solder wire to the junction of the iron tip and the joint—NOT directly to the iron tip.

Why not to the tip: Solder applied to the tip picks up flux contamination and temperature gradients that prevent proper joint formation. The solder must flow into the joint by being attracted to the hot surfaces.

How much solder: Solder amount is one of the most common beginner struggles.

Too little solder:

- Insufficient fillet coverage

- Weak mechanical joint

- Potential for open circuit

Too much solder:

- Large blobs that may bridge to adjacent pads

- Hides the joint structure (can’t see if it wetted properly)

- Wastes material and looks unprofessional

The right amount: For a standard through-hole joint, you want solder to fill the hole and form a small concave fillet (cone shape) on both top and bottom of the board, with the component lead just visible at the apex. The fillet should rise from the pad smoothly, reaching the lead and curving concavely back in—like a small volcano shape.

Technique:

- Feed solder slowly, watching how it flows

- Stop when the fillet looks right

- Practice on scrap boards to develop feel for correct quantity

Step 4: Remove Solder and Iron

Order of removal:

- Remove the solder wire first

- Remove the iron immediately after

Why this order: Removing solder first stops adding material. Removing the iron immediately prevents overheating the joint or disturbing it during the critical initial cooling phase.

Tip departure angle: Sweep the iron away cleanly. Don’t drag or twist as you remove it—this can create solder bridges or disturb the cooling joint.

Step 5: Let It Cool—Without Moving

Critical step: Do not move the component or PCB while the solder is cooling.

Solder transitions from liquid through a pasty semi-solid stage before fully solidifying. Any movement during this stage creates a “disturbed joint”—a cold-looking, grainy joint with compromised reliability.

Cooling time: Through-hole joints are typically fully solid within 3–5 seconds. You can gently blow on them to accelerate cooling. Don’t use compressed air (can spread flux residue) or water (thermal shock).

Step 6: Inspect the Joint

Before moving to the next joint, inspect what you just made.

Visual inspection: A good leaded-solder joint:

- Shiny surface: Mirror-like appearance

- Smooth fillet: Concave curves from pad to lead

- Correct volume: Lead visible but well covered

- No bridges: Isolated from adjacent pads

A good lead-free solder joint:

- Slightly matte: Acceptable—does NOT mean cold joint

- Smooth surface: No rough granularity

- Good coverage: Same fillet shape as leaded

- No bridges: Isolated

Signs of a bad joint:

- Dull, grainy texture (leaded only—cold joint)

- Rough, lumpy, or bumpy surface

- Solder beaded up like a ball (insufficient wetting)

- Lead not visible (too much solder)

- No concave fillet (too little solder or poor wetting)

- Bridge to adjacent pad

Step 7: Trim the Lead

After soldering, trim the component lead flush with the solder joint:

- Use flush-cut diagonal cutters

- Position cutters flat against the solder dome

- Cut in one clean motion

- Hold the waste lead piece as you cut (flying fragments are hazardous!)

- Check trimmed joint—trimming shouldn’t disturb the joint

Soldering Through-Hole Components

Standard Resistors and Capacitors

These are the best starting point for beginners—leads are robust, pads are large, and polarity is usually not an issue for resistors.

Process:

- Insert component from top side of board

- Bend leads slightly to hold component in place

- Flip board to access solder side

- Solder each lead (1–2 seconds contact, small amount of solder)

- Trim leads

- Inspect

Key challenges:

- Keeping resistor body flat against board (bend leads properly)

- Using correct amount of solder (practice)

- Not heating too long (may damage resistor or lift pad)

Electrolytic Capacitors

Critical: Electrolytic capacitors are polarized—reverse installation destroys them and can cause violent failure!

Identifying polarity:

- Longer lead = positive (+)

- Shorter lead = negative (−)

- White stripe on body = negative

- Marking on PCB: (+) or (−) symbol, stripe indicates negative

Process: Same as resistors, but double-check orientation before soldering.

Diodes and LEDs

Also polarized: Even more important than capacitors.

Diode identification:

- Stripe on body = cathode (negative terminal)

- Matches stripe/line on PCB silkscreen

- Longer lead typically anode (positive) for LEDs

LEDs: Take extra care not to overheat—modern LEDs are more heat tolerant than old types, but excessive heat still damages them. Work quickly or use heat sink clips on leads.

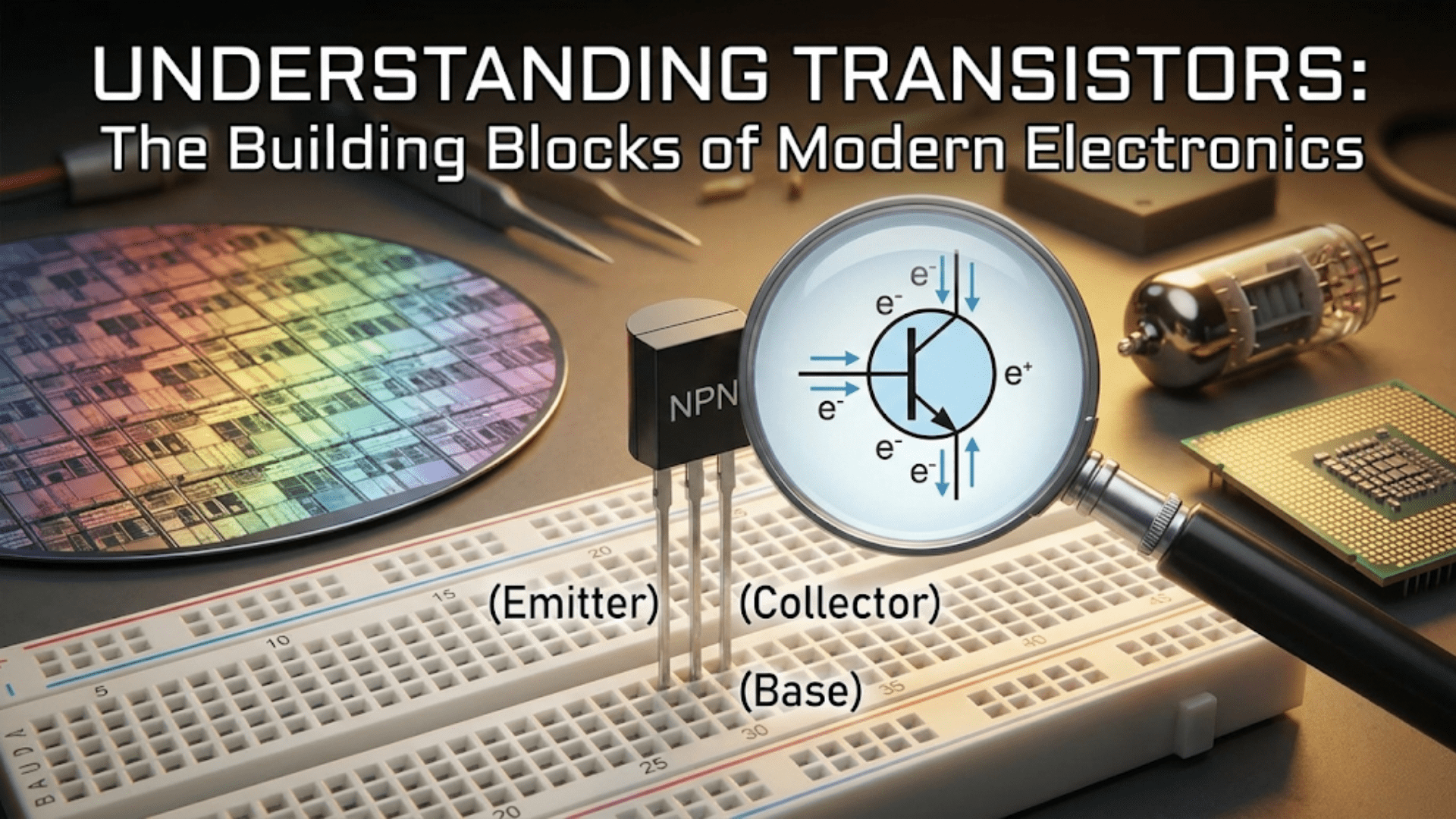

Integrated Circuits (ICs)

Orientation critical: ICs installed backwards are destroyed when power is applied.

Orientation markers:

- Notch or dimple at pin 1 end

- Pin 1 marked with dot or triangle

- Pin numbering goes counter-clockwise from pin 1

DIP ICs (Dual Inline Package):

- Insert carefully—all pins in correct holes, none bent under

- Solder one corner pin, verify alignment, then opposite corner

- Solder remaining pins in diagonal order to prevent thermal warping

IC sockets: Many builders use IC sockets—solder the socket, then insert the IC separately. This protects the IC from heat and allows easy replacement.

Multi-Pin Connectors

Challenge: Multiple pins in a row require avoiding solder bridges between adjacent pins.

Technique:

- Solder one end pin first, check alignment, then solder opposite end pin

- Solder remaining pins with brief contacts

- Inspect for bridges between pins using magnification

- Remove bridges with desoldering wick

Common Soldering Problems and Solutions

Cold (Dry) Joints

Appearance: Dull, grainy, rough surface; solder looks like it’s stuck to surfaces rather than flowed

Cause: Insufficient heat—either joint wasn’t hot enough, or solder was applied to iron tip rather than joint

Consequences: Poor electrical connection, high resistance, intermittent failure

Fix: Apply flux, reheat joint completely until solder flows, remove iron and let cool undisturbed

Solder Bridges

Appearance: Solder connecting two or more pads or leads that should not be connected

Cause: Too much solder, solder wicked between close pads during cooling

Consequences: Short circuit, circuit malfunction, possible component damage when powered

Fix:

- Apply flux to the bridge

- Touch iron to bridge briefly

- Solder may retract onto pads

- If not: Use desoldering wick placed on bridge, apply iron, wick pulls solder away

Insufficient Solder (Insufficient Fill)

Appearance: Thin, incomplete fillet, pad or hole partially exposed

Cause: Too little solder applied

Consequences: Weak mechanical joint, potential open circuit

Fix: Apply flux, reheat, add small amount of additional solder

Excessive Solder (Oversolder)

Appearance: Large solder blob obscuring lead, excessive volume

Cause: Too much solder applied

Consequences: Bridges, hidden poor joints, unprofessional appearance

Fix: Apply wick to remove excess, or use desoldering pump

Lifted Pads

Appearance: The copper pad has peeled from the PCB substrate

Cause: Excessive heat or mechanical stress while pad was hot

Consequences: Broken circuit trace; requires PCB repair or redesign

Prevention:

- Don’t overheat joints

- Don’t apply force to leads while joint is hot

- Use correct temperature

Fix: Apply conductive epoxy or jumper wire to repair trace

Tombstoning (SMD Components)

Appearance: One end of small SMD component lifts off its pad during soldering (component stands on one end)

Cause: Uneven heating—one pad melts before the other, surface tension pulls component upright

Fix: Reflow with heat on the lifted end while pressing down, or resolder correctly with proper technique

Developing Your Soldering Skills

Practice Strategies

Start with scrap material: Purchase cheap prototype PCBs (perf board) and a bag of old through-hole resistors (or buy specific practice kits). Solder components, desolder them, resolder—repetition builds muscle memory.

Vary component types: Progress through different components: resistors first, then polarized capacitors, then ICs, then fine-pitch connectors.

Self-critique: Examine every joint critically under magnification. If it doesn’t look right, reheat or redo it. Developing a high standard early prevents bad habits.

Document your progress: Photograph early work and compare to later. Progress is often faster than it feels when you’re in the midst of learning.

Building Good Habits

Always tin the tip: Every session starts and ends with a tinned tip. Mid-session, tin whenever the tip looks dark or dirty.

Work clean: Regularly clean the PCB with isopropyl alcohol to remove flux residue, which can be hard to see and can cause leakage current in sensitive circuits.

Temperature discipline: Resist the urge to turn up temperature when having trouble. More often the problem is technique or insufficient flux, not temperature.

One joint at a time: Focus completely on each joint. Rushing leads to errors.

Stay organized: Know where every component goes before you start soldering. Mistakes discovered after soldering require desoldering—more work and risk to the board.

Ergonomics and Safety

Posture and positioning: Soldering hunched over a table for extended periods strains neck and back. Raise the work to eye level when possible. Take breaks every 20–30 minutes.

Flux fume management: Flux fumes from soldering (especially at high temperatures or with large joints) contain chemicals that are irritating to respiratory passages and potentially harmful with extended exposure. Work in a ventilated area, use a fume extractor fan, or use solder with no-clean or low-activity flux formulations.

Burn prevention: The iron tip operates at 300–400°C. Occasional light contact burns are common for beginners—they heal quickly but are a reminder to maintain safe habits. Never leave a hot iron unattended; always return it to its holder.

Eye protection: Solder occasionally sputters or pops (especially at too-high temperature or with contaminated flux). Safety glasses should be worn at all times during soldering.

Soldering vs. Other Connection Methods

| Method | Permanence | Electrical Quality | Mechanical Strength | Skill Required | Reworkability | Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soldering | Permanent | Excellent | Good | Moderate | Moderate | Low | PCBs, general electronics |

| Crimp connectors | Permanent | Very good | Excellent | Low | Difficult | Low–Mod | Wire-to-wire, automotive |

| Wire wrapping | Semi-permanent | Excellent | Good | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Prototyping, telecom |

| Breadboard | Temporary | Good | Poor | Very low | Easy | Low | Prototyping only |

| Screw terminals | Semi-permanent | Good | Good | Very low | Easy | Low–Mod | Field wiring, panels |

| IDC connectors | Permanent | Good | Good | Low | Difficult | Low | Ribbon cable, mass termination |

| Conductive adhesive | Permanent | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Very difficult | Moderate | Flex circuits, heat-sensitive |

| Welding/brazing | Permanent | Excellent | Excellent | High | Very difficult | High | Heavy power, structural |

Conclusion: The Craft Behind the Circuit

Soldering is more than a technical process—it’s a craft that rewards understanding, patience, and practice. Every good solder joint represents the meeting of physics, chemistry, and human skill. Understanding why solder flows, why temperature matters, and why both surfaces must be heated transforms soldering from mysterious to logical, from frustrating to satisfying.

The Journey from Beginner to Competent

Week 1–2: Basic through-hole soldering. Focus on correct technique, not speed. Every joint inspected carefully.

Month 1: Comfortable with resistors, capacitors, connectors, simple ICs. Starting to develop consistent joint appearance.

Month 2–3: Tackling more complex through-hole work, first attempts at SMD soldering. Troubleshooting skills developing.

Month 6+: Confident with most through-hole and basic SMD work. Efficient workflow, consistent results. Beginning to develop personal technique refinements.

Core Principles to Internalize

Heat both surfaces: Never apply solder to the iron; always to the joint.

Flux is your friend: More flux almost always helps. Add extra flux for difficult joints, old components, rework.

The right temperature: Hot enough to solder efficiently, not so hot that components or PCBs are damaged.

Inspect everything: Don’t move to the next joint until the current one looks right.

Practice with purpose: Not just repetition, but critical self-evaluation.

Why Quality Matters

A cold joint or a solder bridge doesn’t just look wrong—it can cause real problems. A high-resistance cold joint creates unpredictable voltage drops. A solder bridge shorts two nets, potentially destroying components when power is applied. A joint with insufficient solder may work initially but fail under vibration or thermal cycling.

For products that go into the field—devices used by real people in real environments—the quality of every solder joint matters. Developing high standards from the beginning ensures that the circuits you build today will still be working years from now.

The Reward of Mastery

There’s a particular satisfaction in looking at a completed, well-soldered board: neat rows of shiny, uniform joints, every component properly placed, no bridges, no cold joints, nothing to fix. It’s the visual signature of careful, skilled work. As you develop your soldering skills, that satisfaction comes more frequently and with less effort—the mark of a skill genuinely mastered.

Pick up the iron, tin the tip, heat the joint, apply the solder. The connection is made. Electronics comes to life. That’s the magic of soldering—permanent, reliable, yours.