Introduction

You’ve spent weeks building an impressive data science project. You cleaned messy data, engineered creative features, trained models, and achieved strong results. But when you share your project on GitHub or discuss it in an interview, something falls flat. The problem isn’t your technical work, it’s how you’re communicating that work to others.

Writing about your data science projects is just as important as building them. Whether you’re creating documentation for a GitHub repository, preparing for job interviews, or publishing a blog post about your work, the ability to clearly communicate your technical decisions and results will set you apart from other candidates. Many data scientists have excellent technical skills but struggle to explain their work in a way that resonates with different audiences.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore how to write about your data science projects effectively. You’ll learn how to structure project documentation, explain technical concepts to non-technical readers, create compelling README files, and tell the story behind your work. By the end, you’ll have a framework for documenting any data science project in a way that showcases your skills and engages your audience.

Why Writing About Your Projects Matters

Before diving into the how, let’s understand why project documentation deserves your attention and effort.

When a hiring manager or recruiter looks at your portfolio, they typically spend just a few minutes on each project. They won’t run your code or dig through your analysis unless something immediately captures their interest. Your writing is what makes that first impression. Good documentation demonstrates that you can communicate complex ideas clearly, a critical skill for any data scientist who needs to present findings to stakeholders.

Moreover, writing about your projects helps you think more deeply about your own work. When you try to explain why you chose a particular algorithm or how you handled missing data, you’re forced to articulate your reasoning. This reflection often reveals gaps in your understanding or opportunities to improve your approach. Many data scientists discover better solutions while writing about their current ones.

Documentation also makes your work accessible to others. If someone wants to build upon your project, contribute to it, or simply learn from your approach, clear writing lowers the barrier to entry. This is particularly important if you’re building a portfolio to showcase during job searches, as you want reviewers to quickly understand the value and sophistication of your work.

Finally, writing about data science is a skill that directly translates to your career. Data scientists regularly write reports, create presentations, and explain their findings to non-technical stakeholders. Practicing these communication skills through project documentation builds the same muscles you’ll use daily in a professional role.

Understanding Your Audience

The first step in writing effectively about your data science projects is identifying who will read your documentation. Different audiences have different needs, backgrounds, and levels of technical expertise. Tailoring your writing to your audience ensures that your message lands effectively.

For technical audiences like other data scientists or machine learning engineers, you can use domain-specific terminology freely. These readers want to understand your methodology, why you made certain technical choices, and how your approach compares to alternatives. They’re comfortable with mathematical notation, algorithm names, and code snippets. When writing for this audience, focus on technical depth, reproducibility, and the reasoning behind your decisions.

Imagine you’re documenting a natural language processing project. For technical readers, you might write something like this: “After experimenting with both TF-IDF and word embeddings, I chose to use pre-trained BERT embeddings fine-tuned on our domain-specific corpus. This approach reduced training time by forty percent compared to training embeddings from scratch while achieving comparable performance on our downstream classification task.”

For non-technical audiences such as hiring managers, recruiters, or business stakeholders, the approach changes dramatically. These readers care more about the problem you solved, the impact of your solution, and the thought process you followed. They want to understand what you accomplished and why it matters, but they don’t need to know the mathematical details of how you accomplished it.

For the same NLP project, you might write for non-technical readers: “Text analysis presented a challenge because computers don’t naturally understand language the way humans do. I solved this by using a modern language understanding system that had already learned from billions of words, then customized it for our specific use case. This let me build an accurate classifier much faster than starting from scratch.”

Some of your readers will fall somewhere in between, with partial technical knowledge or expertise in adjacent fields. These readers might understand general programming concepts but not advanced machine learning, or they might know statistics but not deep learning. For mixed audiences, consider using a layered approach where you provide a clear high-level explanation first, then dive into technical details for those who want them.

The context in which someone reads your documentation also matters. Someone browsing your GitHub portfolio on a mobile device during their commute has different needs than someone sitting at their desk ready to deeply evaluate your technical choices. This means your documentation should work at multiple levels, providing quick wins for skimmers while offering depth for those who want to dig deeper.

The Anatomy of Effective Project Documentation

Let’s break down the essential components of well-documented data science projects. While the specific structure may vary based on your project type and platform, these core elements should appear in most technical documentation.

The project overview serves as your elevator pitch. In three to five sentences, explain what your project does, what problem it solves, and why someone should care. This overview should be understandable to anyone who might encounter your work, regardless of their technical background. Think of it as the abstract of a research paper, it needs to capture the essence of your work without requiring deep domain knowledge.

For example, if you built a housing price prediction model, your overview might read: “This project predicts housing prices in Boston using historical sale data and property characteristics. By analyzing patterns in over fifty thousand transactions, the model helps homebuyers and sellers understand fair market values. The approach achieves a mean absolute error of under fifteen thousand dollars, making it practical for real-world decision support.”

After the overview, provide the motivation and problem statement. Here you explain the real-world problem that inspired your project and why it’s worth solving. This section answers the “why” question that many readers are asking. Even the most technically impressive project loses impact if readers don’t understand why it matters.

When explaining your motivation, connect the problem to real consequences or opportunities. Instead of writing “I wanted to predict customer churn,” try “Customer acquisition costs five times more than customer retention, but most companies don’t realize a customer is at risk until they’ve already left. This project identifies warning signs of churn two months before it happens, giving businesses time to intervene.”

The data section describes what information you worked with, where it came from, and any important characteristics or limitations. Readers need to understand the foundation of your analysis to properly evaluate your results. Be transparent about data quality issues, size limitations, or biases that might affect your conclusions.

Describe your data in concrete terms that paint a picture. Rather than “I used a dataset with demographic and purchase information,” provide specifics: “The dataset contains transaction records for twelve thousand customers over three years, including age, location, purchase frequency, average order value, and customer service interactions. Each row represents one customer’s complete history with the company.”

The methodology section explains your approach to solving the problem. This is where you describe your data processing pipeline, feature engineering choices, models you experimented with, and how you evaluated performance. For technical readers, this section provides the depth they’re looking for. For others, it demonstrates your systematic thinking and problem-solving process.

When describing methodology, explain not just what you did but why you did it. Each decision you made had reasoning behind it, and sharing that reasoning demonstrates thoughtfulness. For instance, instead of “I used random forest,” explain “I chose random forest because it handles non-linear relationships well without requiring manual feature scaling, and it provides feature importance scores that help explain which factors most influence housing prices.”

The results section presents your findings clearly and honestly. Include both quantitative metrics and qualitative insights. Use visualizations to make results accessible, but always provide context for your numbers. A model accuracy of eighty-five percent might be excellent or terrible depending on the baseline and the use case.

Present results in a way that’s meaningful to your audience. If you’re writing for data scientists, include metrics like precision, recall, and F1 scores with appropriate context. For broader audiences, translate these metrics into business impact: “The model correctly identifies ninety percent of customers who will churn, allowing the retention team to focus their efforts on the right people rather than wasting resources on random outreach.”

Finally, include a discussion of limitations and future work. No project is perfect, and acknowledging limitations demonstrates maturity and honesty. This section shows that you understand the boundaries of your work and can think critically about it. It also provides a roadmap for anyone who might want to extend your project.

When discussing limitations, be specific rather than generic. Instead of “more data would improve results,” try “The model struggles with luxury properties above five hundred thousand dollars because they represent only two percent of the training data. Collecting more high-end transactions would likely improve predictions in this segment.”

Crafting an Excellent README File

The README file is the front door to your project. On GitHub and similar platforms, it’s the first thing people see when they visit your repository. A well-crafted README can be the difference between someone engaging with your work or moving on to the next project.

Start with a clear, descriptive title that immediately tells readers what the project is about. Avoid vague names like “Machine Learning Project” or “Data Analysis.” Instead, use titles that convey both the domain and the approach: “Predicting Customer Churn Using Ensemble Methods” or “Analyzing Air Quality Trends Across US Cities.”

After the title, include badges if appropriate. Badges are small visual indicators that show things like build status, test coverage, or the programming language used. While not essential, they add a professional polish and quickly communicate key information about your project’s status and quality.

Your README should begin with a compelling introduction that combines your project overview and motivation. This opening section needs to hook readers immediately. Start with the problem you’re solving, then briefly explain your approach and results. Someone should be able to read just this section and understand whether your project is relevant to their interests.

Here’s an example of an effective introduction:

“Every year, millions of students apply to colleges without understanding their realistic chances of admission. This project uses machine learning to predict college acceptance probability based on GPA, test scores, extracurricular activities, and demographic factors. By training on admissions data from over one hundred thousand applications across fifty universities, the model provides personalized predictions with eighty-two percent accuracy. This tool helps students make informed decisions about where to apply, potentially saving thousands of dollars in application fees.”

Following the introduction, include a table of contents if your README is longer than a few screens. This helps readers navigate directly to the sections most relevant to them. For shorter READMEs, you can skip this and let readers scroll naturally.

The features or highlights section briefly showcases what makes your project interesting or unique. This is your opportunity to emphasize specific accomplishments, innovative approaches, or particularly interesting findings. Think of this as the highlights reel that makes someone want to explore further.

You might include items like:

“This project demonstrates advanced feature engineering by creating interaction terms between demographic variables and temporal patterns, resulting in a fifteen percent improvement over baseline models. The analysis reveals surprising patterns in seasonal application trends that contradict common wisdom about college admissions timing. All code is fully documented and includes unit tests, making it easy to adapt for different datasets or educational contexts.”

The installation and usage section provides practical instructions for anyone who wants to run your code. This is crucial for reproducibility and demonstrates that you understand how others will interact with your work. Include step-by-step instructions that assume minimal prior knowledge. Someone should be able to follow your instructions and run your project without having to make assumptions or fill in gaps.

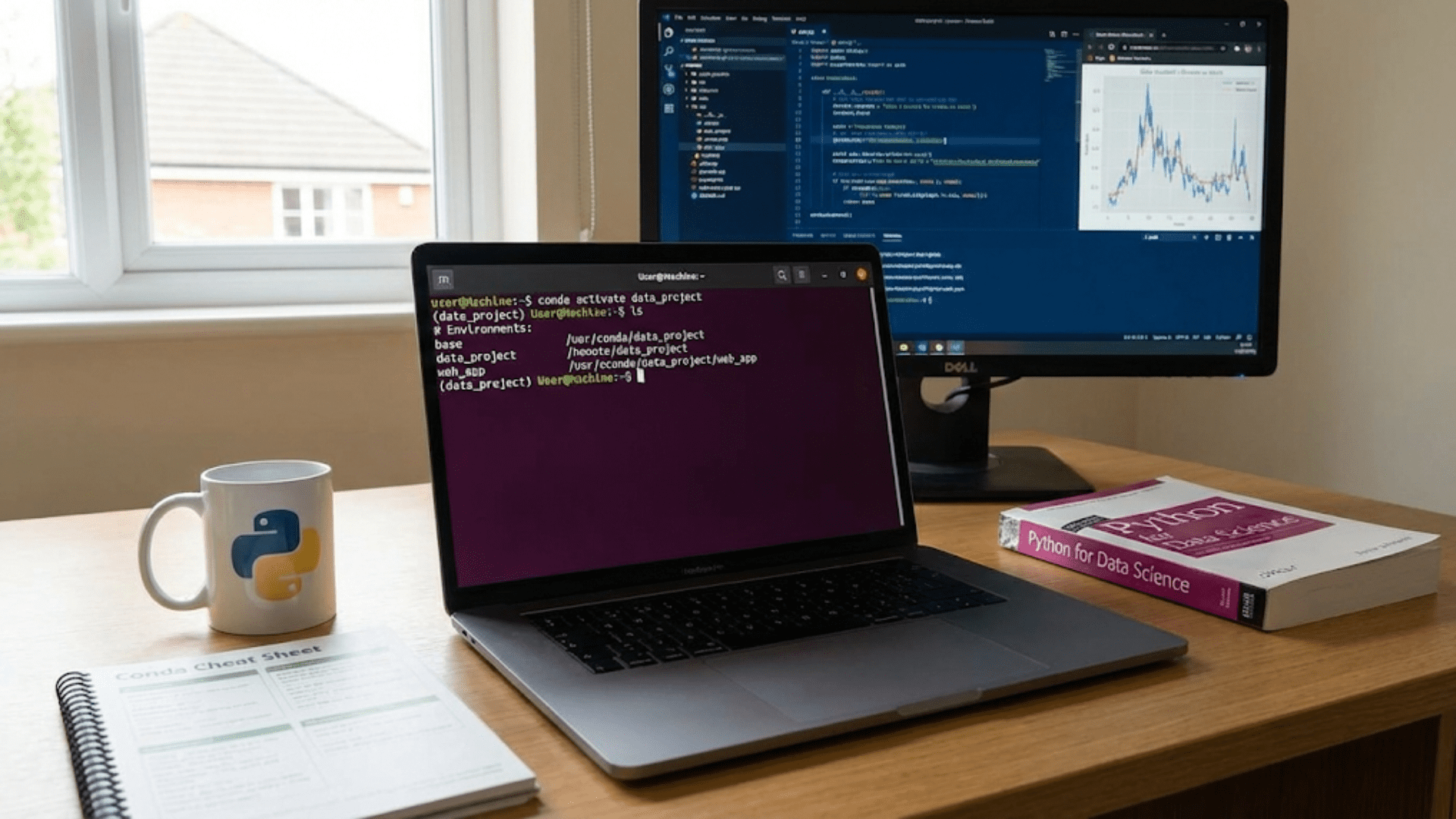

Start with dependencies and requirements. List the Python version you used and all required packages. Many data scientists include a requirements.txt file, but also provide a brief explanation in the README itself. Explain how to set up a virtual environment if your project has specific version requirements.

For example:

“This project requires Python 3.8 or higher and uses several data science libraries. To set up your environment, first create a virtual environment to isolate dependencies. Then install the required packages using pip. The main dependencies include pandas for data manipulation, scikit-learn for machine learning models, and matplotlib for visualization. A complete requirements file is included in the repository.”

After explaining setup, provide clear usage instructions. Show exactly how someone would run your project, including any command-line arguments or configuration options. If your project includes multiple scripts or notebooks, explain what each one does and in what order they should be run.

Consider including a minimal working example that someone can run immediately to see results. This could be a simplified version of your analysis or a demo mode that uses a small sample of data. Getting someone from zero to seeing results in under five minutes dramatically increases engagement with your project.

The project structure section helps readers understand how your files are organized. For larger projects, this roadmap is invaluable for navigation. Provide a brief description of what each major file or directory contains.

You might format this as:

“The repository is organized into several directories, each serving a specific purpose. The data directory contains raw and processed datasets, with separate subdirectories to keep original data separate from cleaned versions. The notebooks directory includes Jupyter notebooks for exploratory data analysis, feature engineering, and model development, each named to indicate the analysis stage. The src directory contains the core Python modules, including data processing functions, model training code, and evaluation utilities. The tests directory includes unit tests for the main functions, ensuring code reliability. Finally, the results directory stores model outputs, performance metrics, and generated visualizations.”

Include a methodology or approach section that explains your technical process at a medium level of detail. This is more in-depth than your overview but more accessible than diving into the code itself. Explain your data cleaning process, feature engineering decisions, model selection rationale, and evaluation methodology.

The key is to explain not just the steps you took but the reasoning behind them. When you describe preprocessing, explain why you handled missing values the way you did. When discussing feature engineering, explain what patterns or relationships you were trying to capture. When presenting model choices, explain why you selected certain algorithms over others.

Your results section should showcase your findings with both text and visualizations. Include key performance metrics, but always provide context for interpreting them. A confusion matrix means little without explaining what the rows and columns represent and why certain types of errors matter more than others in your specific use case.

Make your visualizations self-contained by including clear titles, axis labels, and legends. A plot should be understandable even if someone only sees that image without reading the surrounding text. In the README, explain what each visualization shows and what patterns or insights it reveals.

The contributing section is particularly important if you hope others might extend or improve your work. Explain how someone could contribute, whether you’re accepting pull requests, and any guidelines for contributing. Even if you’re not actively seeking collaborators, including this section signals that you write code with others in mind.

End your README with acknowledgments and licensing information. Credit any datasets you used, papers that inspired your approach, or online resources that helped you solve problems. Include a license that explains how others can use your code. For portfolio projects, the MIT License is popular because it’s permissive while requiring attribution.

Writing for Different Platforms

The platform where you share your project influences how you should write about it. A GitHub README, a blog post, and interview talking points each serve different purposes and require different approaches.

For GitHub and portfolio repositories, your README is paramount. This is where you invest the most effort in comprehensive documentation. GitHub READMEs can be longer and more detailed because readers who visit your repository are actively seeking information about your project. They’ve made a conscious choice to learn more, so they’re willing to engage with more content.

On GitHub, take advantage of markdown formatting to create a well-structured, scannable document. Use headers to break up sections, code blocks to show examples, images to illustrate results, and links to connect to other resources. The visual hierarchy helps readers navigate even longer documents.

For blog posts or articles about your projects, the approach shifts toward storytelling and education. Blog readers want narrative and insights, not just technical documentation. Start with a hook that draws readers in, build tension around the problem you’re solving, and take readers on a journey through your thought process.

Blog posts benefit from a more conversational tone than formal documentation. You can inject personality, share frustrations you encountered, and explain dead ends you explored before finding your solution. These human elements make your writing more engaging and help readers connect with your experience.

When writing a blog post about a project, structure it around the story of discovery rather than the final methodology. Instead of presenting your approach as a fait accompli, take readers through your thinking process. Explain why you initially thought one approach would work, what you learned when it didn’t, and how that led you to your eventual solution.

For interview discussions about your projects, you need a different format entirely. You can’t hand someone a ten-page document during an interview. Instead, prepare a flexible framework that lets you discuss your project at different levels of depth depending on the interviewer’s questions and interests.

Start with a one-minute elevator pitch that covers the problem, approach, and results. This is your default response when someone says “tell me about this project.” From there, have three-minute and ten-minute versions prepared that add progressively more detail. The three-minute version might add context about your methodology and key insights, while the ten-minute version could include discussion of alternatives you considered and lessons learned.

Practice talking about your projects without relying on visuals or code. In many interviews, you won’t have the opportunity to share your screen. You need to paint pictures with words, using analogies and clear explanations to make your technical work accessible.

For social media platforms like LinkedIn or Twitter, brevity is essential. Distill your project down to one or two key insights or accomplishments that fit in a short post. Use these platforms to drive traffic to more detailed documentation elsewhere rather than trying to explain everything in the post itself.

On LinkedIn, you might write: “Just completed a customer segmentation analysis that identified three distinct user groups, each requiring different retention strategies. The data revealed that our high-value customers actually engage less frequently but spend more per transaction. This insight is reshaping how we approach customer communication. Full analysis and methodology on GitHub.”

Explaining Technical Concepts Clearly

One of the biggest challenges in writing about data science is explaining technical concepts to audiences with varying levels of expertise. The key is to build understanding progressively, starting from familiar concepts and gradually introducing complexity.

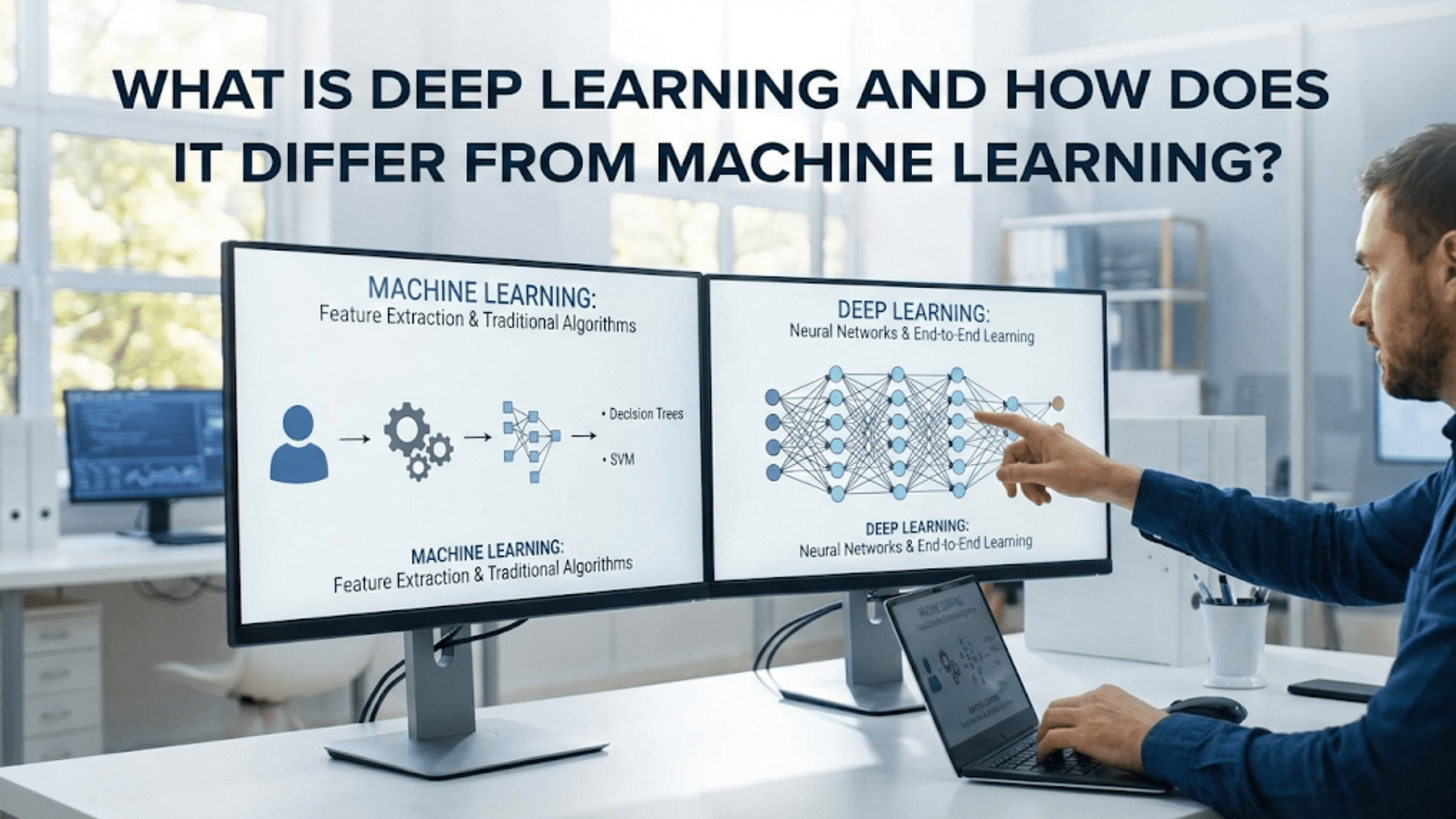

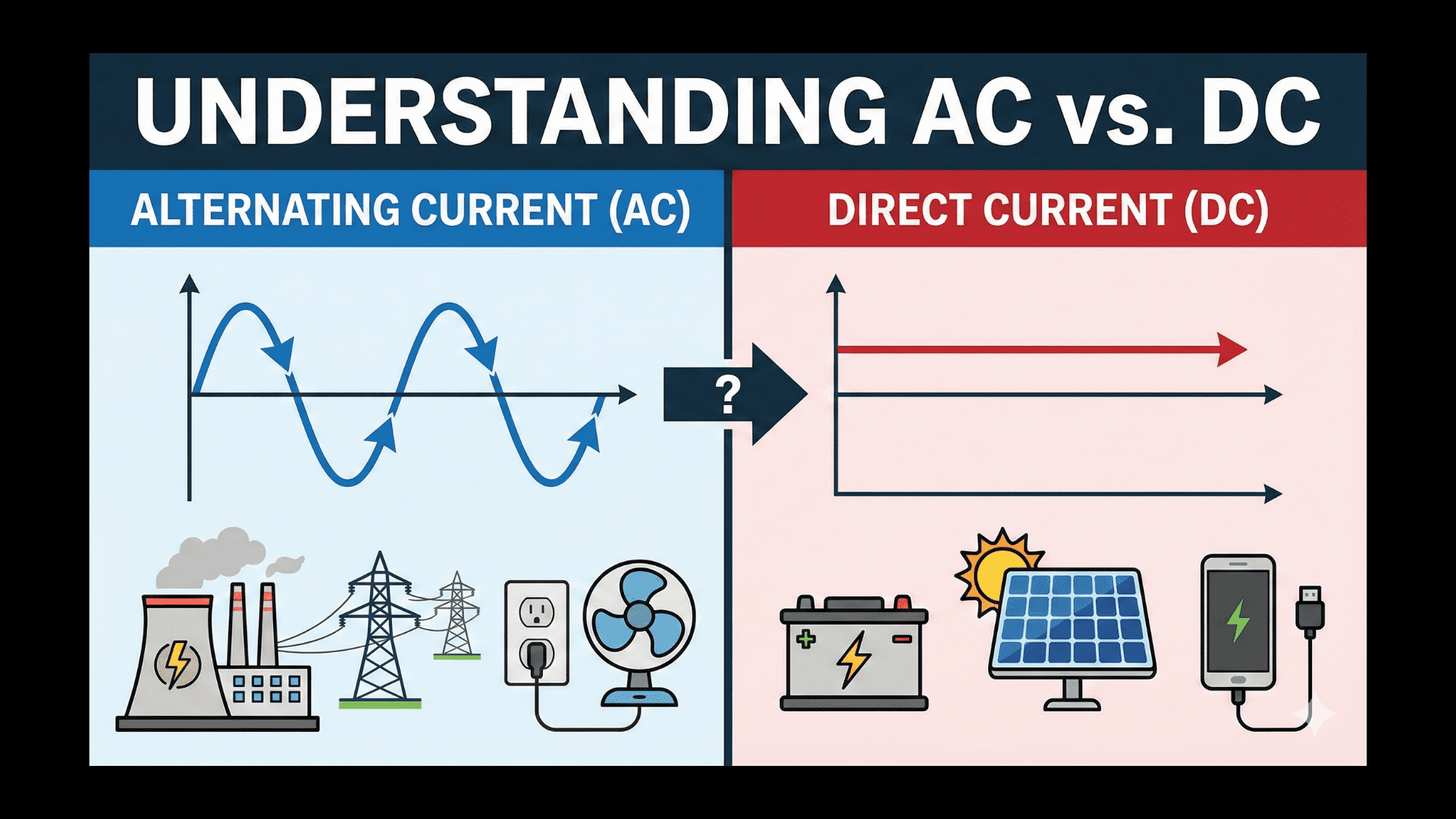

Use analogies to connect new ideas to things your audience already understands. Analogies are particularly powerful for explaining machine learning concepts that might seem abstract. For example, explaining gradient descent as “like finding the lowest point in a foggy valley by always walking downhill, even though you can’t see the entire landscape” gives readers an intuitive grasp before you introduce mathematical details.

When introducing technical terms, define them briefly when they first appear. Don’t assume readers know what “feature engineering” or “cross-validation” means, even in documentation aimed at data scientists. A quick definition costs you little space but dramatically improves accessibility. You might write “feature engineering, the process of creating new variables from existing data to help models identify patterns.”

Break complex processes into steps. If you’re explaining a machine learning pipeline, separate data cleaning from feature engineering, model training, and evaluation. Describe each step independently before showing how they connect. This prevents cognitive overload and helps readers build understanding incrementally.

Use concrete examples to illustrate abstract concepts. When explaining how your model makes predictions, walk through a specific example with actual values. Instead of “the model weighs multiple features to make predictions,” show how it works: “For a house with three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and fifteen hundred square feet in a suburban neighborhood, the model weighs each factor. The neighborhood adds about fifty thousand dollars to the base price, each bedroom adds twenty thousand, and each bathroom adds fifteen thousand, resulting in a predicted price of three hundred thousand dollars.”

Visualize whenever possible. A simple diagram can often explain a concept more clearly than paragraphs of text. Flow charts show process flows, scatter plots reveal relationships, bar charts compare performance metrics, and confusion matrices illustrate classification errors. When you include visualizations, always explain what readers should notice in them.

Avoid jargon when simpler words work just as well. Instead of “leveraging ensemble methodologies,” write “combining multiple models.” Instead of “implemented dimensionality reduction,” write “reduced the number of features.” Clear, straightforward language makes your writing accessible without sacrificing technical accuracy.

When you must use technical terminology, explain why that specific term matters. If you’re discussing regularization, don’t just define it. Explain the problem it solves: “Without regularization, the model memorizes the training data too closely and fails to generalize. Regularization prevents this by penalizing overly complex patterns, helping the model focus on genuine relationships rather than noise.”

Layer your explanations from simple to complex. Start with the high-level concept, then add details for readers who want them. You might first explain that neural networks learn by adjusting connection weights, then add that they use backpropagation to calculate adjustments, then finally note that the chain rule of calculus enables this calculation. Readers can stop at whatever level of detail satisfies their curiosity.

Telling Your Project Story

Every data science project has a narrative arc, even if it doesn’t feel like a story while you’re building it. Learning to surface and communicate that narrative makes your project documentation more engaging and memorable.

Your project story typically begins with recognizing a problem or opportunity. Maybe you noticed something interesting in data you work with regularly, read about a technique you wanted to try, or identified a decision that could be improved with better information. This origin story helps readers understand your motivation and makes the technical work that follows more meaningful.

When sharing your project’s beginning, be specific about what sparked your interest. Instead of “I wanted to practice machine learning,” try “After reading about ensemble methods in a research paper, I wondered whether they could improve the customer churn models my company uses. I decided to test this hypothesis using publicly available telecommunications data.”

The middle of your story is where you encounter and solve problems. This is where most of the technical work happens, but it’s also where many project descriptions become dry and formulaic. Make this section engaging by sharing the challenges you faced and how you overcame them.

Don’t present your methodology as if you knew exactly what to do from the start. In reality, data science is full of false starts, unexpected problems, and iterative refinement. Sharing these moments makes your story more authentic and demonstrates valuable problem-solving skills.

You might write something like: “My first attempt at feature engineering created over fifty variables, which seemed comprehensive. But when I trained the model, it performed worse than a simpler baseline. After analyzing feature importance scores, I realized many variables were redundant or capturing noise rather than signal. I refined my approach to focus on just the twelve most informative features, which improved both performance and interpretability.”

Include the surprises and insights you discovered along the way. Often the most interesting parts of a data science project are the unexpected patterns you uncover or the assumptions you discover were wrong. These moments of discovery keep readers engaged and showcase your analytical thinking.

The conclusion of your story presents your results and their implications. But rather than just stating final metrics, connect your findings back to the original problem. Explain what your results mean for decision-making, what insights they provide, or what questions they raise.

Good conclusions also acknowledge limitations and suggest future directions. This shows intellectual honesty and demonstrates that you understand the boundaries of your work. It also provides natural conversation starters if you’re discussing the project in an interview.

Throughout your narrative, maintain a balance between technical details and accessibility. The story arc provides structure that helps readers follow along even when technical concepts get complex. By embedding technical information within a narrative framework, you make it easier for readers to absorb and remember.

Common Documentation Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced data scientists make common mistakes when writing about their projects. Being aware of these pitfalls helps you avoid them and create more effective documentation.

One frequent mistake is assuming too much knowledge. You might think everyone knows what a random forest is or understands what accuracy means, but many readers don’t. When in doubt, add a brief explanation. It’s better to over-explain slightly than to lose readers who don’t understand your terminology.

Another common error is focusing exclusively on what worked while omitting what didn’t. Your failed experiments and iterative improvements are often more instructive than your final approach. Discussing what you tried and why it didn’t work demonstrates problem-solving skills and makes your eventual solution more impressive.

Many data scientists under-explain their data. They might mention using “housing data” without describing what features the dataset contains, how many observations it includes, or what limitations it has. Readers need this context to evaluate your work properly. Always describe your data in enough detail that someone could roughly understand what they’re looking at without seeing it.

Presenting results without context is another frequent issue. Saying your model achieved eighty-five percent accuracy means little without knowing the baseline, the class balance, or what accuracy metric you’re using. Always provide comparison points and explain why your results are good, bad, or surprising.

Over-complicating explanations is a mistake that stems from trying to sound more sophisticated. Using unnecessarily complex language or focusing on minor technical details that don’t impact the core story makes your writing harder to follow without adding value. Aim for clarity over complexity.

Neglecting visual consistency hurts readability. If you use screenshots or plots, make sure they’re consistently sized and formatted. If you include code snippets, use consistent syntax highlighting and formatting. These small details contribute to a professional, polished appearance.

Forgetting to explain why you made specific choices leaves readers wondering about your thought process. When you chose one algorithm over another, handled missing data a certain way, or selected particular features, there were reasons for those decisions. Sharing your reasoning demonstrates thoughtfulness and helps readers learn from your approach.

Finally, many data scientists write documentation only after completing a project, trying to remember decisions they made weeks or months earlier. This results in incomplete or inaccurate explanations. Document as you go, keeping notes about challenges, decisions, and insights while they’re fresh. This makes final documentation much easier and more accurate.

Practical Examples and Templates

To make these concepts concrete, let’s look at some before-and-after examples of project descriptions, showing how to improve weak documentation.

Here’s a weak project description:

“This project predicts credit card fraud using machine learning. I used a dataset from Kaggle with transaction data. After cleaning the data and creating features, I trained several models including logistic regression, random forest, and XGBoost. XGBoost performed best with ninety-eight percent accuracy. The code is in the notebook.”

This description has several problems. It’s vague about the problem being solved, provides no context for the data or results, doesn’t explain methodology, and gives no insight into the thought process. Let’s improve it:

“Credit card fraud costs the financial industry billions annually, and detecting it requires identifying suspicious transactions in milliseconds among millions of legitimate purchases. This project builds a fraud detection system using machine learning to flag potentially fraudulent transactions while minimizing false alarms that frustrate customers.

The analysis uses a public dataset of European credit card transactions containing just under two hundred thousand transactions, of which only a fraction of a percent are fraudulent. This extreme class imbalance presents a key challenge, as a model that simply labels everything as legitimate would be highly accurate but completely useless.

To address this imbalance, I experimented with several approaches including oversampling the minority class, undersampling the majority class, and using cost-sensitive learning. The most effective approach was SMOTE oversampling combined with ensemble methods that can learn from imbalanced data.

I engineered features focused on transaction timing patterns, amount statistics, and historical customer behavior. For example, I created features capturing whether a transaction amount was unusual compared to a customer’s typical spending, and whether the transaction time was suspicious for that customer.

After testing logistic regression, random forest, and gradient boosting models, XGBoost emerged as the strongest performer. However, I evaluated models using the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve rather than simple accuracy, since correctly identifying the rare fraud cases matters far more than overall accuracy. The final model achieves a precision of ninety-two percent and recall of eighty-seven percent, meaning it catches most fraud while keeping false alarms manageable. In production, this would flag roughly thirteen transactions for every actual fraud case, a reasonable trade-off that allows manual review of suspicious activity.”

This improved version provides context about why fraud detection matters, explains the data and its challenges, describes the methodology and reasoning behind choices, and presents results with appropriate metrics and business interpretation.

Here’s a template structure you can adapt for your own projects:

Project Title: [Specific, Descriptive Name]

Overview: [Two to three sentences explaining what the project does and why it matters]

The Problem: [Describe the real-world problem or question you’re addressing, why it’s important, and what challenges it presents]

The Data: [Explain the dataset size, key features, where it came from, and any important limitations or characteristics]

My Approach: [Describe your methodology, including data processing, feature engineering, model selection, and evaluation strategy. Explain key decisions and trade-offs]

Key Insights: [Share interesting patterns or findings from your analysis, especially anything surprising or counter-intuitive]

Results: [Present quantitative and qualitative results with appropriate context and comparison points]

Limitations and Future Work: [Discuss what your project doesn’t address and how it could be extended or improved]

Technical Details: [Provide implementation specifics, dependencies, and instructions for reproducing your work]

This template provides a solid foundation that you can customize based on your project type, audience, and platform.

Maintaining and Updating Documentation

Writing documentation isn’t a one-time activity. As your project evolves and as you receive feedback, you’ll need to update and refine your documentation to keep it accurate and useful.

When you make significant changes to your project, update the relevant documentation sections immediately. Don’t let documentation drift out of sync with your code. If you change your data processing pipeline, update the methodology section. If you improve model performance, update the results. Keeping documentation current prevents confusion and demonstrates professionalism.

Pay attention to questions people ask about your project. If multiple people ask about the same thing, that’s a signal your documentation isn’t clear in that area. Use questions as feedback to identify gaps or confusing sections, then revise those parts to address the common confusion.

Consider adding a changelog to more substantial projects. This simple addition helps readers understand how your project has evolved over time. You might note when you added new features, fixed bugs, or improved performance. For portfolio projects, a changelog shows that you continue to maintain and improve your work rather than abandoning it after the initial commit.

Version your documentation along with your code. If you use Git, documentation updates should be part of your commits. This creates a history of how your explanations and understanding evolved alongside the technical implementation.

Periodically review your old documentation with fresh eyes. After you’ve learned more or worked on other projects, you might find better ways to explain concepts or identify issues you didn’t notice originally. Set a reminder to review major portfolio projects every few months and make small refinements.

Respond to feedback graciously and use it to improve. If someone points out an error or suggests a better explanation, thank them and consider implementing their suggestion. This not only improves your documentation but also shows you’re receptive to feedback and collaborative.

Conclusion

Writing effectively about your data science projects is a skill that develops with practice and intention. By understanding your audience, structuring your documentation thoughtfully, explaining technical concepts clearly, and telling the story behind your work, you can create project documentation that showcases your abilities and engages readers.

Remember that good documentation serves multiple purposes simultaneously. It helps others understand and build upon your work, demonstrates your communication skills to potential employers, and deepens your own understanding through the act of explaining. The time you invest in writing about your projects pays dividends throughout your data science career.

Start with your next project by documenting as you go rather than trying to remember everything afterward. Use the templates and frameworks from this guide as starting points, then adapt them to your specific needs and style. Pay attention to what works and what doesn’t, and continuously refine your approach.

Most importantly, recognize that communication is just as fundamental to data science as technical skills. The best analysis in the world has no impact if you can’t explain it to others. By developing your ability to write about your work clearly and compellingly, you’re not just creating better documentation, you’re becoming a more effective data scientist.

As you continue building your portfolio and working on projects, remember that every project is an opportunity to practice and improve your technical communication. With each README you write, each blog post you publish, and each project you present, you’ll become more skilled at translating complex technical work into clear, engaging narratives that resonate with your audience. This skill will serve you throughout your entire data science career, from landing your first job to leading teams and influencing strategy years down the line.