Introduction

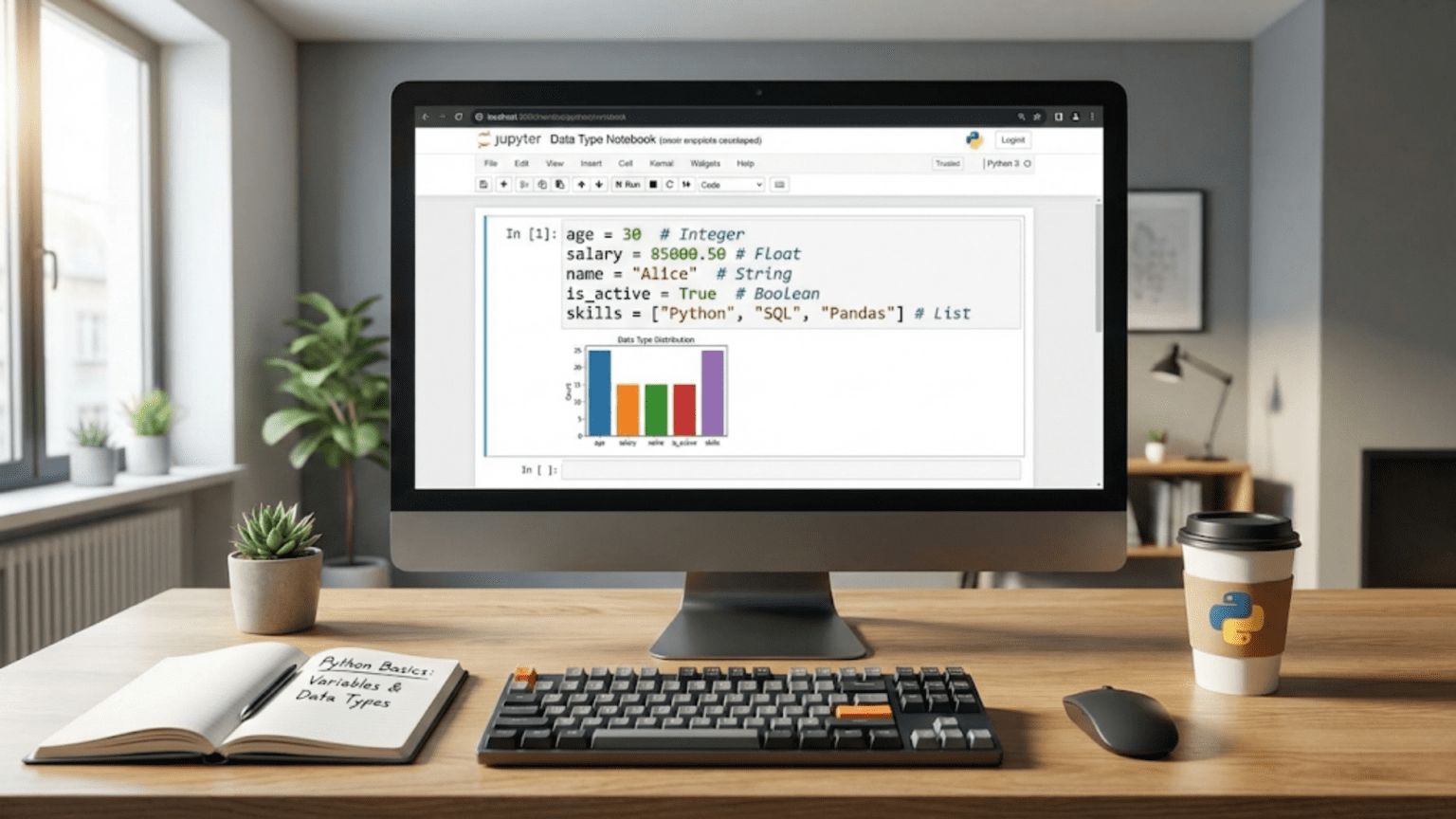

Every data science journey begins with Python fundamentals, and nothing is more fundamental than understanding how Python stores and organizes information through variables and data types. If programming is a language for communicating instructions to computers, then variables are the nouns of that language, representing things we want to work with, and data types are the categories that determine what kinds of operations we can perform on those things. Just as you would not try to subtract names or divide words in English, Python has rules about which operations work with which types of data.

For aspiring data scientists, mastering these basics provides the foundation upon which all your future work will build. When you eventually analyze datasets with pandas, build models with scikit-learn, or create visualizations with matplotlib, you will constantly work with variables holding different types of data. Understanding how Python treats integers differently from floating-point numbers, or how strings behave differently from lists, prevents countless frustrating bugs and helps you write code that does exactly what you intend. These concepts might seem simple initially, but deep understanding of how Python handles data at this fundamental level separates programmers who struggle with mysterious errors from those who write confident, correct code.

The beautiful aspect of learning Python for data science is that you can see results immediately. Unlike some programming concepts that remain abstract until you have substantial experience, variables and data types let you store real information and perform meaningful operations from your very first lines of code. You can store your age and height as numbers, perform calculations on them, store your name as text, and combine these pieces of information in useful ways. This immediate feedback makes learning both rewarding and practical as you quickly move from abstract concepts to working code that accomplishes real tasks.

This comprehensive guide will take you from never having written a line of Python through confident understanding of how Python stores and manages different types of information. You will learn what variables are and how they let you store information for later use, understand Python’s main data types and why each exists, discover how Python determines data types automatically while also letting you control them when needed, master the operations you can perform on different types of data, and develop intuition about when to use each type in your data science work. By the end, you will have solid foundations for the more advanced Python topics that follow, and you will be writing simple but meaningful Python programs with confidence.

Understanding Variables: Containers for Your Data

Before we can explore different types of data, we need to understand the concept of variables, which are simply named containers that hold information you want to work with. Think of a variable as a labeled box where you can store something and retrieve it later by referring to the label. When you need that information again, you just use the variable name and Python retrieves whatever you stored there.

Creating your first variable in Python requires just an equals sign, which in programming we call the assignment operator. Let us create a variable to store someone’s age. You write the variable name on the left, the equals sign in the middle, and the value you want to store on the right, like this:

age = 28What happened here? You created a variable named age and stored the number 28 in it. Python now remembers this association between the name age and the value 28. Whenever you write age in your code from this point forward, Python substitutes the value 28. You can verify this by asking Python to print the value:

print(age) # This will display: 28The beauty of variables becomes apparent when you want to use the same value multiple times or perform calculations. Instead of writing the number 28 repeatedly throughout your code, you write age, and if you later need to change the age, you only update it in one place. This might not seem important with a single number, but imagine analyzing data with thousands of values or building models with dozens of parameters. Variables make your code both readable and maintainable.

Variable names in Python follow specific rules that you need to internalize. Names can contain letters, numbers, and underscores, but they must start with a letter or underscore, never a number. Python distinguishes between uppercase and lowercase letters, so age, Age, and AGE represent three completely different variables. By convention, data scientists and Python programmers typically use lowercase names with underscores separating words for readability, like user_age or customer_count. This style, called snake_case, makes your code easier for others and your future self to read.

Some words have special meaning in Python and cannot be used as variable names. These reserved keywords like if, for, while, and def serve specific purposes in the language. Python will raise an error if you try to use them as variable names. Additionally, while you can technically use names like list or sum, doing so overrides Python’s built-in functions with those names, which creates confusing bugs later. Stick with descriptive names that clearly indicate what information the variable holds.

Choosing good variable names dramatically affects code readability. Compare these two examples storing the same information:

# Poor variable names

x = 45000

y = 0.15

z = x * y

# Clear, descriptive variable names

salary = 45000

tax_rate = 0.15

tax_amount = salary * tax_rateBoth versions do the same thing mathematically, but the second version immediately tells you what the code represents without requiring mental translation. When you return to your code weeks later or share it with colleagues, descriptive names save everyone time and prevent misunderstandings. This practice becomes even more important in data science where code often analyzes complex datasets or implements sophisticated models.

Variables in Python are remarkably flexible compared to some other programming languages. You can reassign variables to hold different values at any time, and Python does not complain if the new value has a different type than the original. This flexibility makes Python feel intuitive and natural, though you should use it thoughtfully to avoid confusing code:

temperature = 72 # Starting as a number

print(temperature) # Displays: 72

temperature = "warm" # Now reassigned to text

print(temperature) # Displays: warmWhile Python allows this flexibility, reassigning variables to completely different types often signals that you should probably use different variable names to keep your code clear. However, updating variables to new values of the same general type is extremely common and useful, like incrementing a counter or accumulating a sum:

total_cost = 0 # Start with zero

total_cost = total_cost + 10 # Add 10

total_cost = total_cost + 15 # Add 15 more

print(total_cost) # Displays: 25This pattern of taking the current value, modifying it, and storing the result back in the same variable appears constantly in programming. Python even provides shorthand for this common operation. Instead of writing total_cost = total_cost + 10, you can write total_cost += 10, which means exactly the same thing but saves typing.

Numeric Data Types: Working with Numbers

Numbers form the foundation of data science, whether you are calculating statistics, training models, or analyzing measurements. Python provides several numeric data types, each suited for different purposes. Understanding when to use each type helps you write efficient code that behaves exactly as you intend.

Integers represent whole numbers without decimal points, like someone’s age, the number of customers, or the count of items in a category. Python creates integers automatically when you assign whole numbers to variables:

num_students = 250

year = 2024

negative_value = -42Integers can be positive, negative, or zero, and Python handles arbitrarily large integers without overflow errors that plague some other languages. This means you can work with massive numbers without worrying about exceeding limits:

huge_number = 99999999999999999999

bigger_number = huge_number * huge_number

print(bigger_number) # Python handles this just fineFor data science work, integers commonly represent counts, indexes, categorical labels encoded as numbers, or any measurement naturally expressed as whole numbers. When you count the number of rows in a dataset, filter data by year, or specify how many clusters you want in a clustering algorithm, you work with integers.

Floating-point numbers, which Python calls floats, represent numbers with decimal points. These handle measurements that fall between whole numbers, like temperatures, heights, percentages, or probabilities:

temperature = 72.5

height_meters = 1.73

probability = 0.85

pi_approximation = 3.14159Python automatically creates floats when you include a decimal point in a number, even if the decimal part is zero. Writing 5.0 instead of 5 explicitly creates a float rather than an integer. While this distinction might seem pedantic, it occasionally matters in calculations or when functions expect specific numeric types.

Floating-point numbers have important limitations you need to understand. Computers represent floats using finite binary representation, which means some decimal numbers cannot be represented exactly. This leads to tiny rounding errors that occasionally surprise beginners:

result = 0.1 + 0.2

print(result) # Displays: 0.30000000000000004 instead of exactly 0.3This behavior is not a Python bug but a fundamental characteristic of how computers store decimal numbers. For most data science work, these tiny errors do not matter because they are far smaller than measurement precision or modeling uncertainty. However, you should never use exact equality comparisons with floats. Instead of checking if two floats are equal, check if they are very close:

# Don't do this

if result == 0.3:

print("Equal")

# Do this instead

if abs(result - 0.3) < 0.0001: # Check if difference is tiny

print("Equal for practical purposes")Arithmetic operations with numbers work intuitively in Python, using standard mathematical operators. Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division work as you would expect:

a = 10

b = 3

sum_value = a + b # Addition: 13

difference = a - b # Subtraction: 7

product = a * b # Multiplication: 30

quotient = a / b # Division: 3.3333...Notice that division always produces a float in Python 3, even when dividing evenly divisible integers like 10 / 2. If you specifically want integer division that discards any remainder, use the double-slash operator:

integer_quotient = 10 // 3 # Result: 3 (discards the remainder)

remainder = 10 % 3 # Modulo operator gives remainder: 1Exponentiation uses two asterisks:

squared = 5 ** 2 # 5 to the power of 2: 25

cubed = 2 ** 3 # 2 to the power of 3: 8

square_root = 9 ** 0.5 # Taking the 0.5 power gives square root: 3.0Python follows standard mathematical order of operations, evaluating expressions from left to right while respecting precedence rules where multiplication and division happen before addition and subtraction. Parentheses override these rules when you need different order:

result1 = 2 + 3 * 4 # Multiplication first: 2 + 12 = 14

result2 = (2 + 3) * 4 # Parentheses first: 5 * 4 = 20Type conversion between integers and floats happens automatically in most situations through a process called type coercion. When you mix integers and floats in calculations, Python converts integers to floats to perform the operation:

mixed = 5 + 2.5 # Integer 5 becomes float 5.0, result is 7.5You can also explicitly convert between types when needed using int() and float() functions:

float_version = float(42) # Converts integer 42 to float 42.0

int_version = int(3.7) # Converts float to integer, truncating: 3Notice that converting float to integer truncates toward zero, discarding everything after the decimal point rather than rounding. If you want rounding instead, use the round() function:

rounded = round(3.7) # Rounds to nearest integer: 4

rounded_down = round(3.4) # Rounds to nearest integer: 3Boolean Data Type: Working with True and False

Boolean values represent truth and falsehood, the fundamental concept underlying all logic and decision-making in programming. Python has exactly two boolean values: True and False, both capitalized. While this might seem overly simple, booleans power every conditional statement, every filter applied to data, every if-statement that makes decisions, and every loop that continues while some condition holds true.

Creating boolean variables works just like creating numeric variables:

is_raining = True

has_umbrella = False

is_data_clean = TrueBooleans most commonly arise from comparison operations that ask questions about relationships between values. Python provides comparison operators that evaluate to True or False:

age = 25

is_adult = age >= 18 # True, since 25 is greater than or equal to 18

is_teenager = age < 20 # False, since 25 is not less than 20

is_exactly_25 = age == 25 # True, since age equals 25

is_not_30 = age != 30 # True, since age is not equal to 30Notice the double equals sign for equality comparison. This is crucial because a single equals sign means assignment while double equals asks if two values are equal. Confusing these causes common beginner errors:

# Assignment - stores 5 in x

x = 5

# Comparison - checks if x equals 5, returns True

is_five = x == 5You can combine multiple boolean expressions using logical operators: and, or, and not. These let you express complex conditions:

temperature = 75

is_sunny = True

# Both conditions must be true

perfect_weather = temperature > 70 and is_sunny # True

# At least one condition must be true

acceptable_weather = temperature > 80 or is_sunny # True

# Reverses the boolean value

is_cloudy = not is_sunny # FalseUnderstanding how Python evaluates these compound expressions helps you write correct logic. The and operator returns True only when both conditions are true. The or operator returns True when at least one condition is true. The not operator flips True to False and False to True.

Python considers certain values “truthy” or “falsy” even when they are not explicitly True or False. This concept, called truthiness, means you can use many types of values in boolean contexts:

# Empty collections are falsy

empty_list = []

if not empty_list: # This executes because empty list is falsy

print("The list is empty")

# Non-zero numbers are truthy

count = 5

if count: # This executes because 5 is truthy

print("Count is non-zero")

# Empty strings are falsy

name = ""

if not name: # This executes because empty string is falsy

print("Name is empty")Generally, empty or zero values evaluate as falsy while non-empty or non-zero values evaluate as truthy. The specific falsy values in Python include False, None, zero of any numeric type, empty sequences like empty strings or lists, and empty dictionaries or sets. Everything else evaluates as truthy.

This truthiness concept proves particularly useful in data science when checking if datasets contain records, if calculations produced non-zero results, or if strings contain text. Rather than explicitly comparing to zero or checking lengths, you can often test values directly in conditional statements.

String Data Type: Working with Text

Strings represent text data in Python, storing sequences of characters like names, addresses, product descriptions, or any textual information. While data science heavily emphasizes numbers, textual data appears constantly in real datasets, from customer reviews to categorical variables to column headers. Understanding strings thoroughly proves essential for data cleaning, feature engineering, and text analysis.

Creating strings requires enclosing text in quotes. Python accepts either single or double quotes, treating them identically:

name = "Alice"

city = 'Boston'

message = "It's a beautiful day" # Double quotes let you include apostrophes

alternative = 'She said "hello"' # Single quotes let you include double quotesFor longer text spanning multiple lines, use triple quotes:

paragraph = """This is a longer piece of text

that spans multiple lines. Triple quotes

preserve all the line breaks."""Strings in Python are sequences of characters, which means many operations treat them as ordered collections you can examine character by character. You can find the length of a string using the len() function:

message = "Hello, World!"

length = len(message) # Result: 13 (includes punctuation and space)Individual characters can be accessed by position using square brackets, with positions starting at zero. This zero-based indexing feels unnatural initially but becomes second nature with practice:

greeting = "Hello"

first_letter = greeting[0] # 'H' - first character at position 0

second_letter = greeting[1] # 'e' - second character at position 1

last_letter = greeting[4] # 'o' - fifth character at position 4Negative indexes count from the end of the string, with -1 referring to the last character:

greeting = "Hello"

last = greeting[-1] # 'o' - last character

second_last = greeting[-2] # 'l' - second to last characterCombining strings, called concatenation, uses the plus operator:

first_name = "Jane"

last_name = "Smith"

full_name = first_name + " " + last_name # "Jane Smith"String repetition uses the multiplication operator:

emphasis = "Ha" * 3 # "HaHaHa"

separator = "=" * 20 # "===================="String formatting provides cleaner ways to insert variables into strings than concatenation. Modern Python favors f-strings, which prefix strings with f and embed expressions in curly braces:

name = "Alice"

age = 30

message = f"My name is {name} and I am {age} years old."

# Result: "My name is Alice and I am 30 years old."F-strings can include any Python expression, not just variables:

price = 42.5

message = f"The price with tax is ${price * 1.08:.2f}"

# The :.2f formats the number to 2 decimal places

# Result: "The price with tax is $45.90"Strings provide numerous methods for common text operations. Methods are functions that belong to specific types of objects, called using dot notation:

text = "Hello, World!"

uppercase = text.upper() # "HELLO, WORLD!"

lowercase = text.lower() # "hello, world!"

title_case = text.title() # "Hello, World!"

starts = text.startswith("Hello") # True

ends = text.endswith("!") # True

contains = "World" in text # True

cleaned = " spaces ".strip() # Removes leading/trailing whitespace: "spaces"

replaced = text.replace("World", "Python") # "Hello, Python!"

parts = text.split(", ") # Splits on ", " into list: ["Hello", "World!"]These string methods prove invaluable for data cleaning tasks like standardizing text, removing unwanted characters, or parsing structured text. Many pandas operations for working with text columns build directly on these string methods.

Strings in Python are immutable, meaning once created, they cannot be changed. Methods like upper() or replace() create new strings rather than modifying the original:

original = "Hello"

modified = original.upper()

print(original) # Still "Hello" - unchanged

print(modified) # "HELLO" - new stringThis immutability prevents certain bugs but means you must assign results of string operations to variables when you want to keep them.

Understanding Type Checking and Conversion

Python determines variable types automatically based on the values you assign, a feature called dynamic typing. This flexibility makes Python feel intuitive but occasionally produces surprises when types do not match your expectations. Learning to check types and convert between them gives you full control over how Python treats your data.

The type() function reveals what type Python assigned to a value:

integer_var = 42

float_var = 3.14

string_var = "Hello"

bool_var = True

print(type(integer_var)) # <class 'int'>

print(type(float_var)) # <class 'float'>

print(type(string_var)) # <class 'str'>

print(type(bool_var)) # <class 'bool'>This function proves invaluable when debugging unexpected behavior or when you receive data from external sources and need to verify its type before processing.

Type conversion functions let you explicitly change values from one type to another when needed. We have already seen int() and float() for converting numbers. Similarly, str() converts values to strings:

# Converting to strings

age_str = str(25) # "25" as text, not a number

pi_str = str(3.14) # "3.14" as text

bool_str = str(True) # "True" as text

# Converting to numbers

int_from_str = int("42") # 42 as integer

float_from_str = float("3.14") # 3.14 as float

# Converting to boolean

bool_from_int = bool(1) # True (any non-zero number is True)

bool_from_str = bool("text") # True (any non-empty string is True)

bool_from_zero = bool(0) # FalseBe careful when converting strings to numbers. Python raises an error if the string does not represent a valid number:

# This works fine

valid = int("123")

# This causes an error

invalid = int("hello") # ValueError: invalid literal for int()When working with user input or data from files, you should often validate that strings contain expected formats before attempting conversion, or handle potential errors gracefully using techniques you will learn later.

Type conversion happens automatically in some contexts through type coercion. We saw this with mixed numeric operations where integers automatically become floats. However, Python will not automatically convert between incompatible types like strings and numbers:

# This works - automatic conversion

result = 5 + 2.0 # 5 becomes 5.0, result is 7.0

# This fails - cannot add string and number

invalid = "5" + 2 # TypeError: can only concatenate str to strUnderstanding when automatic conversion happens versus when you must convert explicitly prevents many common errors. As a general rule, Python converts between compatible types like int and float automatically but refuses to guess how to combine very different types like strings and numbers.

The None value deserves mention as a special type representing the absence of a value. Unlike zero or empty strings, None explicitly means “no value here”:

result = None # Represents absence of value

if result is None:

print("No result yet")You will encounter None frequently in data science when dealing with missing data, optional function arguments, or initializing variables before you have actual values to store. Checking for None uses the is operator rather than equality comparison:

value = None

if value is None: # Correct way to check

print("Value is None")Practical Examples for Data Science

Now that you understand Python’s basic data types, let us see how they apply to realistic data science scenarios. These examples illustrate why understanding types matters for your future work.

Imagine you are analyzing survey data where respondents provided their age, income, and whether they own a home. You might store this information using appropriate types:

respondent_age = 34 # Integer for whole number age

annual_income = 75000.0 # Float for precise monetary amount

owns_home = True # Boolean for yes/no question

respondent_name = "Sarah Martinez" # String for text name

survey_date = "2024-01-15" # String for date (for now)

# Calculate some basic statistics

income_per_year_of_age = annual_income / respondent_age

income_formatted = f"${annual_income:,.2f}" # Formats as $75,000.00

homeowner_status = "homeowner" if owns_home else "renter"

print(f"{respondent_name} is {respondent_age} years old")

print(f"Annual income: {income_formatted}")

print(f"Status: {homeowner_status}")Converting between types often appears in data cleaning. Suppose you read numerical data from a file where everything arrives as strings:

# Data from file arrives as strings

age_string = "28"

height_string = "1.75"

is_member_string = "True"

# Convert to appropriate types for analysis

age = int(age_string)

height = float(height_string)

is_member = is_member_string == "True" # Convert string to boolean

# Now you can perform calculations

age_in_months = age * 12

height_in_inches = height * 39.37

print(f"Age: {age} years ({age_in_months} months)")

print(f"Height: {height} meters ({height_in_inches:.1f} inches)")

print(f"Membership status: {is_member}")Boolean logic helps filter data based on multiple conditions:

# Analyzing if a customer qualifies for a discount

purchase_amount = 150

is_member = True

is_first_purchase = False

# Discount applies if purchase exceeds 100 AND customer is member

# OR if this is their first purchase

qualifies_for_discount = (purchase_amount > 100 and is_member) or is_first_purchase

discount_rate = 0.15 if qualifies_for_discount else 0

final_price = purchase_amount * (1 - discount_rate)

print(f"Original price: ${purchase_amount}")

print(f"Qualifies for discount: {qualifies_for_discount}")

print(f"Final price: ${final_price:.2f}")String manipulation frequently appears when cleaning text data:

# Raw customer feedback from survey

raw_feedback = " VERY SATISFIED with the product! "

# Clean and standardize the feedback

cleaned = raw_feedback.strip() # Remove extra spaces

standardized = cleaned.lower() # Convert to lowercase

sentiment = "positive" if "satisfied" in standardized else "negative"

print(f"Raw: '{raw_feedback}'")

print(f"Cleaned: '{cleaned}'")

print(f"Standardized: '{standardized}'")

print(f"Detected sentiment: {sentiment}")These examples demonstrate how variables and data types form the foundation for all data science work. Whether loading datasets, performing calculations, filtering records, or transforming text, you constantly work with these fundamental building blocks.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Understanding common pitfalls helps you avoid frustration as you write your first Python programs. These mistakes appear in nearly every beginner’s code, so recognizing and preventing them accelerates your learning.

Using single equals instead of double equals for comparison remains the most common error:

# Wrong - assigns 5 to x instead of comparing

if x = 5: # This causes a syntax error

print("x is 5")

# Correct - compares x to 5

if x == 5:

print("x is 5")Python actually prevents this error in if statements by raising a syntax error, but in other contexts the distinction matters tremendously.

Forgetting that strings require quotes leads to errors where Python thinks you are referring to variables:

# Wrong - Python looks for variable named Hello

message = Hello # NameError: name 'Hello' is not defined

# Correct - quotes indicate text

message = "Hello"Type mismatches when combining values cause errors:

# Wrong - cannot directly add string and number

result = "Age: " + 25 # TypeError

# Correct - convert number to string first

result = "Age: " + str(25)

# Or use f-strings which handle conversion automatically

result = f"Age: {25}"Confusing zero-based indexing when accessing string characters causes off-by-one errors:

word = "Python"

# Remember: first character is at position 0, not 1

first = word[0] # 'P'

last = word[5] # 'n' - the sixth character

# word[6] would cause an error - no seventh character existsForgetting that string methods return new strings rather than modifying originals:

message = "hello"

message.upper() # This returns "HELLO" but doesn't save it

# Wrong - message is still "hello"

print(message)

# Correct - save the result

message = message.upper()

print(message) # Now prints "HELLO"These mistakes become less frequent with practice as you internalize Python’s rules and develop intuition about how code behaves.

Conclusion

Variables and data types form the absolute foundation of Python programming for data science. Every analysis you conduct, every model you build, and every visualization you create begins with storing information in variables of appropriate types and performing operations that respect how Python treats different kinds of data. The concepts covered in this guide, while basic, appear in every line of data science code you will ever write.

Understanding that integers represent whole numbers suitable for counts and indexes, floats handle decimal values for measurements and calculations, booleans capture true or false conditions that power filtering and logic, and strings store and manipulate text gives you the vocabulary to think clearly about your data. Knowing how to create variables with meaningful names, check and convert types when needed, and perform appropriate operations on different types prevents countless errors and makes your code both correct and readable.

The investment you make in truly understanding these fundamentals pays dividends throughout your entire data science journey. When you later work with pandas DataFrames, you will recognize that each column has a data type determining what operations are valid. When you build machine learning models, you will need to ensure numerical features are actually stored as numbers rather than strings. When you clean messy datasets, you will use string methods and type conversions constantly. These basics never stop being relevant, they simply become so automatic that you stop thinking consciously about them.

As you progress to the next articles in this series, you will build on these foundations with more complex data structures, control flow, and eventually the specialized libraries that make Python powerful for data science. But those topics all assume you understand variables and basic types thoroughly. Practice writing small programs that use different types, experiment with operations and conversions, and make mistakes in safe environments where you can learn from them. With solid mastery of these fundamentals, the more advanced concepts will feel like natural extensions rather than overwhelming complexity.