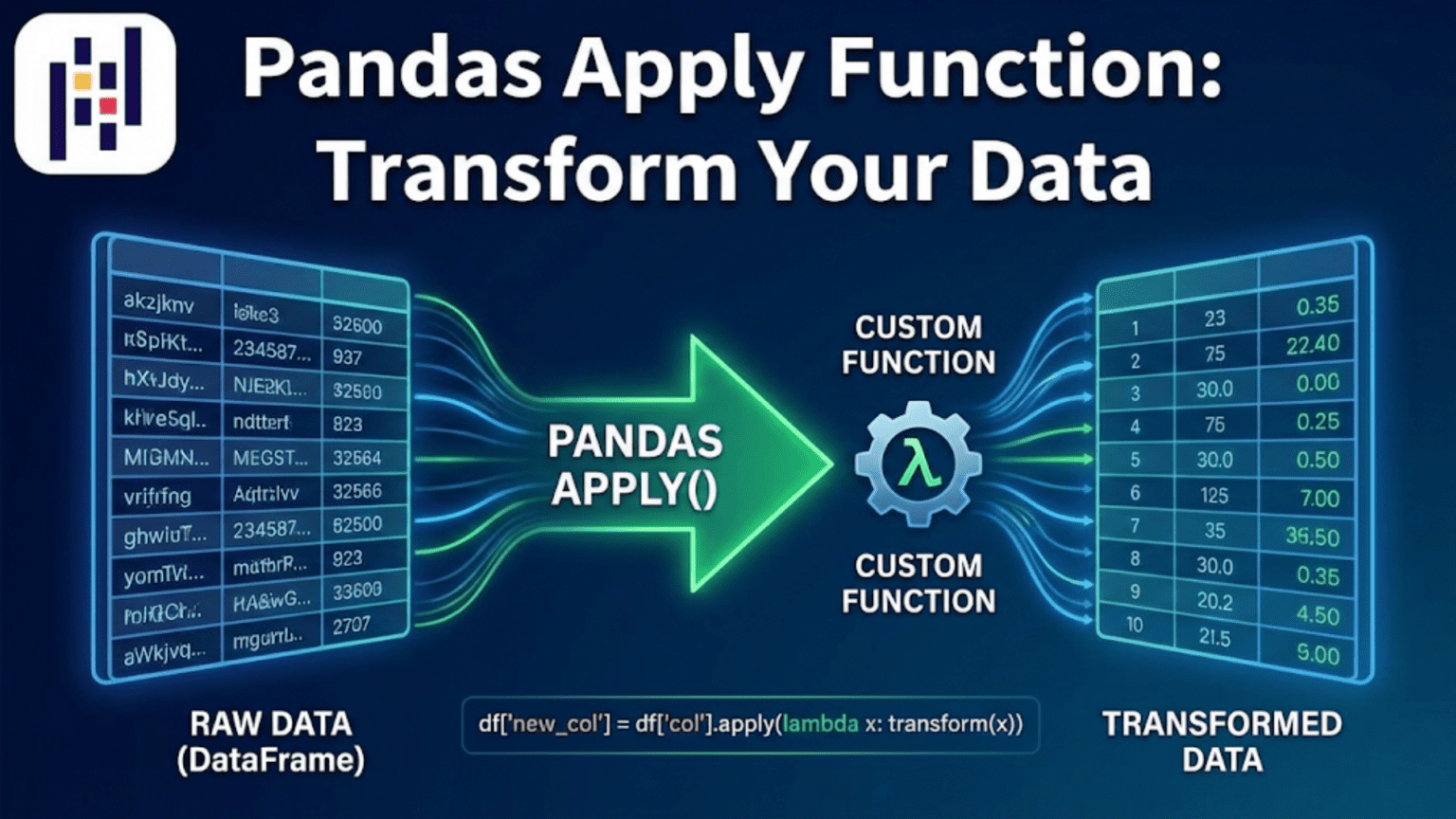

The Pandas apply() function lets you run any custom Python function across a DataFrame’s rows, columns, or a Series element by element. It bridges the gap between Pandas’ built-in vectorized operations and the full flexibility of arbitrary Python logic — making it the go-to tool when no built-in Pandas method exists for the transformation you need.

Introduction: When Built-In Operations Are Not Enough

Pandas ships with an impressive library of built-in operations — arithmetic, string methods via .str, datetime methods via .dt, statistical aggregations, and dozens of others. For the most common data transformations, these built-in operations are fast, concise, and expressive. But real-world data science constantly presents situations where no built-in method exists for what you need to do.

What if you need to classify customers into spending tiers based on a sliding scale formula? What if you need to parse a column of messy addresses into structured components? What if you need to apply a domain-specific scoring function that uses values from multiple columns simultaneously? Or what if you are working with a machine learning preprocessing step that needs to be applied row by row through your DataFrame?

This is exactly where apply() comes in. The apply() function is Pandas’ mechanism for applying any arbitrary Python function — built-in, lambda, or custom-defined — to a Series, to columns of a DataFrame, or to rows of a DataFrame. It is one of the most flexible tools in the entire Pandas ecosystem, and understanding it deeply will make you a significantly more capable data scientist.

In this article, you will learn how apply() works conceptually, how to use it on Series and DataFrames, how to write effective lambda functions and custom functions for it, how to handle common real-world transformation tasks, and when to use apply() versus faster alternatives. Along the way, you will build intuition for choosing the right transformation tool for each situation.

1. The Core Concept: What apply() Does

At its heart, apply() is an iteration mechanism — but one that is integrated with Pandas’ data structures and that supports a wide range of output types. Here is the mental model:

For a Series: apply() calls your function once for each element in the Series, passing the element’s value as the argument. The results are collected and returned as a new Series.

For a DataFrame with axis=0 (default): apply() calls your function once for each column, passing the entire column as a Series. The results are collected per column.

For a DataFrame with axis=1: apply() calls your function once for each row, passing the entire row as a Series. The results are collected per row.

This distinction — especially the difference between axis=0 and axis=1 on a DataFrame — is the most important concept to internalize when learning apply().

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

df = pd.DataFrame({

'A': [1, 2, 3, 4],

'B': [10, 20, 30, 40],

'C': [100, 200, 300, 400]

})

# axis=0 (default): function receives each COLUMN as a Series

col_sum = df.apply(lambda col: col.sum(), axis=0)

print(col_sum)

# A 10

# B 100

# C 1000

# dtype: int64

# axis=1: function receives each ROW as a Series

row_sum = df.apply(lambda row: row.sum(), axis=1)

print(row_sum)

# 0 111

# 1 222

# 2 333

# 3 444

# dtype: int64When axis=0, your function sees one column at a time — the column name is accessible via col.name. When axis=1, your function sees one row at a time — you can access individual column values via row['A'], row['B'], etc.

2. Applying Functions to a Series

Applying a function to a Pandas Series is the simplest use of apply(). It works element by element, transforming each value independently.

2.1 Using Lambda Functions

Lambda functions (anonymous one-liner functions) are the most common companion to apply() on a Series:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

prices = pd.Series([9.99, 24.99, 49.99, 99.99, 199.99])

# Apply a 15% discount to each price

discounted = prices.apply(lambda x: round(x * 0.85, 2))

print(discounted)

# 0 8.49

# 1 21.24

# 2 42.49

# 3 84.99

# 4 169.99

# dtype: float64

# Classify prices into tiers

def price_tier(price):

if price < 20:

return 'Budget'

elif price < 80:

return 'Mid-Range'

else:

return 'Premium'

tiers = prices.apply(price_tier)

print(tiers)

# 0 Budget

# 1 Mid-Range

# 2 Mid-Range

# 3 Premium

# 4 Premium

# dtype: object2.2 Applying Named Functions

You can pass any named function — not just lambdas — to apply(). Named functions are preferable when the logic is complex enough to deserve a name and docstring:

import re

def clean_phone_number(phone):

"""Remove all non-digit characters and format as XXX-XXX-XXXX."""

if pd.isna(phone):

return None

digits = re.sub(r'\D', '', str(phone))

if len(digits) == 10:

return f"{digits[:3]}-{digits[3:6]}-{digits[6:]}"

elif len(digits) == 11 and digits[0] == '1':

return f"{digits[1:4]}-{digits[4:7]}-{digits[7:]}"

else:

return 'Invalid'

phones = pd.Series([

'(555) 123-4567',

'555.987.6543',

'1-800-555-0199',

None,

'12345'

])

cleaned = phones.apply(clean_phone_number)

print(cleaned)

# 0 555-123-4567

# 1 555-987-6543

# 2 800-555-0199

# 3 None

# 4 Invalid

# dtype: object2.3 Passing Extra Arguments with args and kwargs

When your function needs additional parameters beyond the element value, use the args (tuple) or kwargs (dict) parameters in apply():

def apply_tax(price, tax_rate, currency_symbol='$'):

"""Apply a tax rate to a price and format as currency string."""

total = price * (1 + tax_rate)

return f"{currency_symbol}{total:.2f}"

prices = pd.Series([10.00, 25.00, 50.00, 100.00])

# Pass tax_rate via args (positional)

with_tax = prices.apply(apply_tax, args=(0.08,))

print(with_tax)

# 0 $10.80

# 1 $27.00

# 2 $54.00

# 3 $108.00

# Pass additional kwargs

european = prices.apply(apply_tax, args=(0.20,), currency_symbol='€')

print(european)

# 0 €12.00

# 1 €30.00

# 2 €60.00

# 3 €120.003. Applying Functions to DataFrame Columns (axis=0)

When you call apply() on a DataFrame without specifying axis, it defaults to axis=0, passing each column as a Series to your function. This is useful for computing column-level statistics or transformations.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

scores = pd.DataFrame({

'Math': [85, 92, 78, 95, 88],

'Science': [90, 85, 92, 88, 76],

'English': [78, 95, 82, 90, 85]

})

# Apply a custom normalization function to each column

def min_max_normalize(series):

"""Normalize a column to the range [0, 1]."""

return (series - series.min()) / (series.max() - series.min())

normalized = scores.apply(min_max_normalize, axis=0)

print(normalized.round(3))

# Math Science English

# 0 0.412 0.875 0.000

# 1 0.824 0.562 1.000

# 2 0.000 1.000 0.235

# 3 1.000 0.750 0.706

# 4 0.588 0.000 0.412

# Compute a custom summary per column

def column_summary(series):

return pd.Series({

'mean': series.mean(),

'median': series.median(),

'range': series.max() - series.min(),

'cv_%': (series.std() / series.mean() * 100).round(1)

})

summary = scores.apply(column_summary, axis=0)

print(summary)

# Math Science English

# mean 87.6 86.2 86.0

# median 88.0 88.0 85.0

# range 17.0 16.0 17.0

# cv_% 6.3 5.9 5.9When your function returns a Series (as column_summary does), the result is a DataFrame where the returned Series values become the rows. This is a very clean pattern for building custom summary tables.

4. Applying Functions Across Rows (axis=1)

Row-wise application with axis=1 is the most powerful and most commonly needed use of apply() in data science. It lets you write logic that depends on values from multiple columns simultaneously.

4.1 Basic Row-Wise Transformation

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

employees = pd.DataFrame({

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'Diana', 'Edward'],

'base_salary': [75000, 60000, 90000, 55000, 80000],

'years_exp': [4, 2, 8, 1, 6],

'performance': ['Excellent', 'Good', 'Outstanding', 'Good', 'Excellent']

})

# Calculate total compensation based on multiple columns

def calculate_bonus(row):

"""Calculate bonus based on years of experience and performance rating."""

base = row['base_salary']

exp = row['years_exp']

# Base bonus rate by performance

bonus_rates = {

'Outstanding': 0.20,

'Excellent': 0.15,

'Good': 0.08,

'Needs Work': 0.00

}

rate = bonus_rates.get(row['performance'], 0.0)

# Experience multiplier: +1% per year of experience, capped at 10%

exp_boost = min(exp * 0.01, 0.10)

bonus = base * (rate + exp_boost)

return round(bonus, 2)

employees['bonus'] = employees.apply(calculate_bonus, axis=1)

employees['total_comp'] = employees['base_salary'] + employees['bonus']

print(employees[['name', 'base_salary', 'performance', 'years_exp', 'bonus', 'total_comp']])

# name base_salary performance years_exp bonus total_comp

# 0 Alice 75000 Excellent 4 14250.0 89250.0

# 1 Bob 60000 Good 2 6000.0 66000.0

# 2 Charlie 90000 Outstanding 8 25200.0 115200.0

# 3 Diana 55000 Good 1 4950.0 59950.0

# 4 Edward 80000 Excellent 6 16800.0 96800.04.2 Accessing Row Values by Column Name

Inside a row-wise apply() function, the row argument is a Pandas Series with the column names as its index. You access individual values using familiar bracket notation:

def classify_employee(row):

"""Assign a tier label based on multiple criteria."""

salary = row['base_salary']

exp = row['years_exp']

perf = row['performance']

if perf == 'Outstanding' and exp >= 5:

return 'Senior Leader'

elif perf in ('Outstanding', 'Excellent') and salary >= 75000:

return 'High Performer'

elif exp <= 2:

return 'Junior'

else:

return 'Mid-Level'

employees['tier'] = employees.apply(classify_employee, axis=1)

print(employees[['name', 'tier']])

# name tier

# 0 Alice High Performer

# 1 Bob Junior

# 2 Charlie Senior Leader

# 3 Diana Junior

# 4 Edward High Performer4.3 Row-Wise Application Returning Multiple Values

A function applied row-wise can return a Series with multiple named values, which Pandas automatically expands into new columns:

import pandas as pd

orders = pd.DataFrame({

'order_id': [1001, 1002, 1003, 1004],

'subtotal': [120.00, 350.00, 85.00, 500.00],

'region': ['US', 'EU', 'US', 'UK'],

'is_member': [True, False, False, True]

})

def compute_pricing(row):

"""Compute tax, discount, and final price based on multiple factors."""

subtotal = row['subtotal']

region = row['region']

is_member = row['is_member']

# Regional tax rates

tax_rates = {'US': 0.08, 'EU': 0.20, 'UK': 0.20}

tax_rate = tax_rates.get(region, 0.10)

# Member discount

discount_rate = 0.10 if is_member else 0.0

discount_amt = round(subtotal * discount_rate, 2)

# Tax on discounted price

discounted_subtotal = subtotal - discount_amt

tax_amount = round(discounted_subtotal * tax_rate, 2)

final_price = round(discounted_subtotal + tax_amount, 2)

return pd.Series({

'discount': discount_amt,

'tax': tax_amount,

'final_price': final_price

})

# expand=True is implicit when function returns a Series

pricing_cols = orders.apply(compute_pricing, axis=1)

orders_full = pd.concat([orders, pricing_cols], axis=1)

print(orders_full)

# order_id subtotal region is_member discount tax final_price

# 0 1001 120.00 US True 12.00 8.64 116.64

# 1 1002 350.00 EU False 0.00 70.00 420.00

# 2 1003 85.00 US False 0.00 6.80 91.80

# 3 1004 500.00 UK True 50.00 90.00 540.005. applymap() / map() for Element-Wise Operations

Pandas provides two other element-wise application methods that complement apply():

5.1 Series.map() for Element-Wise Mapping

Series.map() is the preferred way to apply element-wise transformations or lookups to a Series. It is similar to Series.apply() but is more explicitly designed for element-level operations and also accepts dictionaries for value mapping:

import pandas as pd

grades = pd.Series(['A', 'B', 'C', 'A', 'D', 'B', 'F'])

# Map using a dictionary (lookup table)

grade_points = {'A': 4.0, 'B': 3.0, 'C': 2.0, 'D': 1.0, 'F': 0.0}

gpa = grades.map(grade_points)

print(gpa)

# 0 4.0

# 1 3.0

# 2 2.0

# 3 4.0

# 4 1.0

# 5 3.0

# 6 0.0

# dtype: float64

# Map using a function

upper_grades = grades.map(lambda g: g.lower())

print(upper_grades)

# Map using another Series (acts as a lookup)

grade_descriptions = pd.Series({

'A': 'Excellent', 'B': 'Good', 'C': 'Average', 'D': 'Below Average', 'F': 'Failing'

})

descriptions = grades.map(grade_descriptions)

print(descriptions)map() vs apply() on Series: For element-wise operations, map() is generally faster and more semantically clear. Use map() when you are transforming individual values; use apply() when your function needs to operate on the Series as a whole (e.g., computing statistics).

5.2 DataFrame.map() for Element-Wise DataFrame Operations

In Pandas 2.1+, DataFrame.map() (formerly called applymap() in older versions) applies a function to every individual element in the entire DataFrame:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

df = pd.DataFrame({

'Q1': [1250.50, 2300.75, 850.25],

'Q2': [1800.00, 1950.50, 1200.00],

'Q3': [2100.75, 2450.00, 1100.50]

})

# Format every number as currency string

# Use map() in Pandas 2.1+, applymap() in older versions

try:

formatted = df.map(lambda x: f"${x:,.2f}")

except AttributeError:

formatted = df.applymap(lambda x: f"${x:,.2f}") # For older Pandas

print(formatted)

# Q1 Q2 Q3

# 0 $1,250.50 $1,800.00 $2,100.75

# 1 $2,300.75 $1,950.50 $2,450.00

# 2 $850.25 $1,200.00 $1,100.506. Practical Comparison Table: apply(), map(), and Vectorized Operations

Choosing the right transformation tool is as important as knowing how to use each one. Here is a comprehensive comparison to guide your decisions:

| Tool | Operates On | Axis | Returns | Speed | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vectorized ops (+, *, etc.) | Element | N/A | Same shape | Fastest | Arithmetic, math operations |

.str methods | Element (strings) | N/A | Series | Very fast | String cleaning and parsing |

.dt methods | Element (dates) | N/A | Series | Very fast | Datetime extraction |

Series.map() | Element | N/A | Series | Fast | Value lookup / substitution |

DataFrame.map() | Element | Both | DataFrame | Fast | Format every cell |

Series.apply() | Element or whole | N/A | Flexible | Moderate | Custom element logic |

DataFrame.apply(axis=0) | Column (Series) | Columns | Series/DF | Moderate | Custom column stats |

DataFrame.apply(axis=1) | Row (Series) | Rows | Series/DF | Slowest | Multi-column row logic |

The key insight from this table: apply() with axis=1 (row-wise) is the slowest option. It should be your last resort, used only when no vectorized alternative exists. For simple operations, always prefer vectorized approaches.

7. Real-World Data Transformation Examples

7.1 Parsing and Cleaning Addresses

import pandas as pd

import re

addresses = pd.DataFrame({

'raw_address': [

'123 Main St, Springfield, IL 62701',

'456 Oak Avenue Apt 2B, Chicago, IL 60601',

'789 Pine Road, Suite 100, Boston, MA 02134',

'New York, NY 10001', # No street address

'321 Elm Blvd, Denver, CO' # No zip code

]

})

def parse_address(addr):

"""Extract components from a raw address string."""

if pd.isna(addr):

return pd.Series({'street': None, 'city': None, 'state': None, 'zip': None})

parts = [p.strip() for p in addr.split(',')]

# Zip code: 5-digit number at end of last part

zip_match = re.search(r'\b(\d{5})\b', parts[-1])

zip_code = zip_match.group(1) if zip_match else None

# State: 2-letter code before zip

state_match = re.search(r'\b([A-Z]{2})\b', parts[-1])

state = state_match.group(1) if state_match else None

# City: second-to-last comma-separated part

city = parts[-2].strip() if len(parts) >= 2 else None

# Street: everything before city

street = ', '.join(parts[:-2]).strip() if len(parts) >= 3 else None

return pd.Series({

'street': street,

'city': city,

'state': state,

'zip_code': zip_code

})

parsed = addresses['raw_address'].apply(parse_address)

result = pd.concat([addresses, parsed], axis=1)

print(result[['street', 'city', 'state', 'zip_code']])

# street city state zip_code

# 0 123 Main St Springfield IL 62701

# 1 456 Oak Avenue Apt 2B Chicago IL 60601

# 2 789 Pine Road, Suite 100 Boston MA 02134

# 3 None New York NY 10001

# 4 321 Elm Blvd Denver CO None7.2 Computing Risk Scores from Multiple Factors

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Loan application data

applications = pd.DataFrame({

'applicant_id': range(1001, 1011),

'credit_score': [750, 580, 680, 720, 640, 800, 560, 700, 620, 780],

'debt_to_income': [0.25, 0.48, 0.35, 0.28, 0.42, 0.18, 0.55, 0.31, 0.45, 0.22],

'loan_amount': [150000, 280000, 200000, 180000, 120000, 400000, 95000, 220000, 160000, 350000],

'employment_yrs': [5, 1, 3, 8, 2, 12, 0, 4, 1, 9],

'has_collateral': [True, False, True, True, False, True, False, True, False, True]

})

def compute_risk_score(row):

"""

Compute a composite risk score (0-100, higher = more risky).

Combines credit score, DTI, loan amount, employment, and collateral.

"""

score = 0

# Credit score risk (0-40 points)

credit = row['credit_score']

if credit >= 750: score += 0

elif credit >= 700: score += 10

elif credit >= 650: score += 20

elif credit >= 600: score += 30

else: score += 40

# Debt-to-income ratio risk (0-25 points)

dti = row['debt_to_income']

if dti < 0.28: score += 0

elif dti < 0.36: score += 8

elif dti < 0.43: score += 16

else: score += 25

# Employment years risk (0-20 points)

emp = row['employment_yrs']

if emp >= 5: score += 0

elif emp >= 3: score += 7

elif emp >= 1: score += 13

else: score += 20

# Collateral reduces risk (0 or -10 points)

if row['has_collateral']:

score -= 10

# High loan amount adds risk (0 or 15 points)

if row['loan_amount'] > 300000:

score += 15

return max(0, min(score, 100)) # Clamp between 0 and 100

def risk_category(score):

if score <= 20: return 'Low Risk'

elif score <= 40: return 'Moderate Risk'

elif score <= 60: return 'High Risk'

else: return 'Very High Risk'

applications['risk_score'] = applications.apply(compute_risk_score, axis=1)

applications['risk_category'] = applications['risk_score'].apply(risk_category)

applications['approved'] = applications['risk_score'] <= 40

print(applications[['applicant_id', 'credit_score', 'debt_to_income',

'risk_score', 'risk_category', 'approved']])7.3 Text Feature Extraction

import pandas as pd

import re

product_reviews = pd.DataFrame({

'review_id': range(1, 6),

'review_text': [

"Absolutely love this product! Works perfectly. 5 stars!",

"Terrible quality. Broke after 2 days. Very disappointed.",

"Decent product for the price. Could be better but ok.",

"AMAZING!!! Best purchase I've made this year. Highly recommend!!!",

"Not great not terrible. Average product, average price."

]

})

def extract_text_features(text):

"""Extract numerical features from a review text string."""

if pd.isna(text):

return pd.Series({

'word_count': 0, 'char_count': 0, 'exclamation_count': 0,

'has_stars': False, 'caps_ratio': 0.0, 'avg_word_length': 0.0

})

words = text.split()

return pd.Series({

'word_count': len(words),

'char_count': len(text),

'exclamation_count': text.count('!'),

'has_stars': bool(re.search(r'\d+\s*stars?', text, re.IGNORECASE)),

'caps_ratio': round(sum(1 for c in text if c.isupper()) / len(text), 3),

'avg_word_length': round(sum(len(w) for w in words) / len(words), 2)

})

text_features = product_reviews['review_text'].apply(extract_text_features)

result = pd.concat([product_reviews[['review_id']], text_features], axis=1)

print(result)

# review_id word_count char_count exclamation_count has_stars caps_ratio avg_word_length

# 0 1 9 55 2 True 0.036 5.33

# 1 2 8 55 0 False 0.036 5.63

# 2 3 10 52 0 False 0.019 4.30

# 3 4 9 64 4 False 0.156 5.22

# 4 5 10 53 0 False 0.019 4.107.4 Group-Aware Scoring with apply() on GroupBy

One of the most powerful patterns is applying a custom function to each group in a groupby() operation:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

sales = pd.DataFrame({

'salesperson': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Alice', 'Charlie', 'Bob', 'Alice', 'Charlie', 'Bob'],

'month': ['Jan', 'Jan', 'Feb', 'Jan', 'Feb', 'Mar', 'Feb', 'Mar'],

'revenue': [12000, 8500, 15000, 11000, 9200, 13500, 14000, 7800]

})

def sales_summary(group):

"""Compute a comprehensive summary for a salesperson's group."""

return pd.Series({

'total_revenue': group['revenue'].sum(),

'avg_monthly': group['revenue'].mean().round(2),

'best_month': group.loc[group['revenue'].idxmax(), 'month'],

'months_active': group['month'].nunique(),

'consistency_cv': round(group['revenue'].std() / group['revenue'].mean() * 100, 1)

})

summary = sales.groupby('salesperson').apply(sales_summary, include_groups=False)

print(summary)

# total_revenue avg_monthly best_month months_active consistency_cv

# salesperson

# Alice 40500 13500.00 Feb 3 10.7

# Bob 25500 8500.00 Jan 3 8.4

# Charlie 25000 12500.00 Feb 2 14.1Using apply() on a GroupBy object passes each group’s sub-DataFrame to your function, giving you full flexibility to compute any metric that requires the entire group’s data.

8. Performance: When to Avoid apply() and What to Use Instead

The most important practical lesson about apply() is knowing when not to use it. Row-wise apply() (with axis=1) is implemented as a Python-level loop and does not benefit from Pandas’ or NumPy’s vectorized C-level optimizations. For large DataFrames, this can be dramatically slower than equivalent vectorized operations.

8.1 The Performance Gap

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import time

# Large DataFrame

n = 100_000

df = pd.DataFrame({

'price': np.random.uniform(10, 1000, n),

'quantity': np.random.randint(1, 50, n),

'tax_rate': np.random.choice([0.05, 0.08, 0.10, 0.20], n)

})

# Method 1: apply() row-wise (SLOW)

start = time.time()

df['revenue_apply'] = df.apply(

lambda row: row['price'] * row['quantity'] * (1 + row['tax_rate']),

axis=1

)

apply_time = time.time() - start

print(f"apply() time: {apply_time:.3f}s")

# Method 2: vectorized operations (FAST)

start = time.time()

df['revenue_vec'] = df['price'] * df['quantity'] * (1 + df['tax_rate'])

vec_time = time.time() - start

print(f"Vectorized time: {vec_time:.4f}s")

print(f"Speedup: {apply_time/vec_time:.0f}x faster with vectorization")

# Verify results are identical

print(f"Results match: {df['revenue_apply'].round(6).equals(df['revenue_vec'].round(6))}")On a typical machine with 100,000 rows, the vectorized approach runs roughly 50–200 times faster than the equivalent apply() call.

8.2 Refactoring apply() to Vectorized Operations

Many operations that beginners write with apply(axis=1) can be refactored to much faster vectorized forms:

# ── BEFORE: apply() approach (slow) ──────────────────────────────────────────

def categorize_slow(row):

if row['age'] < 18:

return 'Minor'

elif row['age'] < 65:

return 'Adult'

else:

return 'Senior'

df['age_category_slow'] = df.apply(categorize_slow, axis=1)

# ── AFTER: np.select() approach (fast) ───────────────────────────────────────

conditions = [

df['age'] < 18,

(df['age'] >= 18) & (df['age'] < 65),

df['age'] >= 65

]

choices = ['Minor', 'Adult', 'Senior']

df['age_category_fast'] = np.select(conditions, choices)

# ── ALTERNATIVE: pd.cut() for binning ────────────────────────────────────────

df['age_category_cut'] = pd.cut(

df['age'],

bins=[0, 17, 64, 150],

labels=['Minor', 'Adult', 'Senior']

)8.3 When apply() Is Actually Appropriate

Despite its relative slowness, apply() is the right tool when:

- Logic is too complex for vectorization: Multi-step branching logic using many columns, external lookups, or stateful computations that cannot be expressed as array operations.

- Working with strings that need regex or multi-step parsing: While

.strmethods cover many cases, complex multi-step parsing often requiresapply(). - Prototyping: When correctness matters more than speed during development; you can always optimize later.

- GroupBy custom aggregations: When

agg()built-in functions are not sufficient. - Small DataFrames: For DataFrames with a few hundred rows, the performance difference is negligible.

9. Best Practices for Writing Effective apply() Functions

9.1 Always Handle Missing Values Explicitly

Your apply() function will receive NaN values if the column contains them. Not handling these will cause errors or produce unexpected results:

def safe_divide(row):

"""Compute revenue/cost ratio, handling zeros and NaN safely."""

revenue = row['revenue']

cost = row['cost']

# Guard against NaN and division by zero

if pd.isna(revenue) or pd.isna(cost) or cost == 0:

return None

return round(revenue / cost, 4)

df['profit_ratio'] = df.apply(safe_divide, axis=1)9.2 Use result_type for Better Output Control

The result_type parameter controls how the results of a row-wise apply() are assembled:

# result_type='expand': expand returned lists/tuples into columns

def get_stats(row):

return [row['revenue'] * 1.1, row['revenue'] * 0.9] # returns a list

# Without result_type='expand', each list becomes a single cell

df_expand = df.apply(get_stats, axis=1, result_type='expand')

# Column 0 = revenue * 1.1, Column 1 = revenue * 0.9

# result_type='reduce': opposite of expand — reduces Series to scalar if possible

# result_type='broadcast': broadcasts scalar results to original shape9.3 Write and Test Functions Independently First

Always test your apply() function on a single row before applying it to the entire DataFrame:

# Test function on a single row before applying to all rows

test_row = employees.iloc[0]

print("Testing on single row:")

print(calculate_bonus(test_row)) # Verify the output is correct

# Then apply to all rows

employees['bonus'] = employees.apply(calculate_bonus, axis=1)9.4 Add Descriptive Docstrings to Custom Functions

Since apply() functions often encapsulate domain logic, clear documentation is especially important:

def score_applicant(row):

"""

Score a loan applicant from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).

Parameters

----------

row : pd.Series

A row containing 'credit_score', 'debt_to_income',

'employment_yrs', and 'has_collateral' columns.

Returns

-------

int

Composite score clamped to [0, 100].

"""

# ... implementation ...9.5 Profile Before Optimizing

Do not prematurely optimize. Write clear, correct apply() code first, then profile it to decide whether optimization is necessary:

import cProfile

# Profile the apply operation to identify bottlenecks

cProfile.run("df.apply(my_function, axis=1)")

# Only optimize if the profiler shows apply() is a significant bottleneck10. Complete Project: Customer Segmentation Pipeline

Let us build a complete customer segmentation pipeline that demonstrates the full power of apply() in a realistic data science context:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import re

np.random.seed(42)

n = 500

# ── Generate realistic customer data ─────────────────────────────────────────

customers = pd.DataFrame({

'customer_id': range(10001, 10001 + n),

'signup_date': pd.date_range('2020-01-01', periods=n, freq='3D').strftime('%Y-%m-%d'),

'last_purchase': pd.date_range('2023-01-01', periods=n, freq='1D').strftime('%Y-%m-%d'),

'total_orders': np.random.poisson(8, n),

'total_spend': np.random.exponential(500, n).round(2),

'avg_rating_given': np.random.uniform(1, 5, n).round(1),

'email': [f'user{i}@example.com' for i in range(n)],

'phone': [f'({np.random.randint(200,999)}) {np.random.randint(200,999)}-{np.random.randint(1000,9999)}'

for _ in range(n)],

'country': np.random.choice(['US', 'UK', 'CA', 'AU', 'DE'], n,

p=[0.55, 0.15, 0.15, 0.08, 0.07]),

'has_subscription': np.random.choice([True, False], n, p=[0.35, 0.65])

})

# Introduce some missing values

customers.loc[np.random.choice(n, 30, replace=False), 'avg_rating_given'] = np.nan

customers.loc[np.random.choice(n, 20, replace=False), 'phone'] = None

print(f"Dataset: {len(customers)} customers")

print(f"Missing ratings: {customers['avg_rating_given'].isna().sum()}")

print(f"Missing phones: {customers['phone'].isna().sum()}")

# ── Step 1: Data cleaning with apply() ───────────────────────────────────────

def clean_phone(phone):

"""Standardize phone number format."""

if pd.isna(phone):

return None

digits = re.sub(r'\D', '', str(phone))

if len(digits) == 10:

return f"{digits[:3]}-{digits[3:6]}-{digits[6:]}"

return None

customers['phone_clean'] = customers['phone'].apply(clean_phone)

# ── Step 2: Feature engineering with apply() ─────────────────────────────────

customers['signup_date'] = pd.to_datetime(customers['signup_date'])

customers['last_purchase'] = pd.to_datetime(customers['last_purchase'])

reference_date = pd.Timestamp('2024-01-01')

def compute_engagement_features(row):

"""Compute RFM-inspired engagement features per customer."""

days_since_purchase = (reference_date - row['last_purchase']).days

tenure_days = (reference_date - row['signup_date']).days

avg_order_value = row['total_spend'] / max(row['total_orders'], 1)

purchase_frequency = row['total_orders'] / max(tenure_days / 30, 1) # orders/month

# Recency score (1-5, higher = more recent)

if days_since_purchase <= 30: recency_score = 5

elif days_since_purchase <= 90: recency_score = 4

elif days_since_purchase <= 180: recency_score = 3

elif days_since_purchase <= 365: recency_score = 2

else: recency_score = 1

return pd.Series({

'days_since_purchase': days_since_purchase,

'tenure_days': tenure_days,

'avg_order_value': round(avg_order_value, 2),

'purchase_frequency': round(purchase_frequency, 3),

'recency_score': recency_score

})

print("\nComputing engagement features...")

engagement = customers.apply(compute_engagement_features, axis=1)

customers = pd.concat([customers, engagement], axis=1)

# ── Step 3: Customer segmentation with apply() ────────────────────────────────

def assign_segment(row):

"""

Assign RFM-based customer segment.

Champions: high recency, high frequency, high value.

At Risk: formerly good customers who haven't purchased recently.

New Customers: recently joined, few purchases.

"""

recency = row['recency_score']

frequency = row['purchase_frequency']

value = row['avg_order_value']

subscribed= row['has_subscription']

if recency >= 4 and frequency >= 1.0 and value >= 300:

return 'Champion'

elif recency >= 4 and subscribed:

return 'Loyal'

elif recency <= 2 and frequency >= 0.5:

return 'At Risk'

elif row['tenure_days'] <= 90:

return 'New Customer'

elif recency >= 3 and value >= 200:

return 'Promising'

else:

return 'Needs Attention'

customers['segment'] = customers.apply(assign_segment, axis=1)

# ── Step 4: Segment analysis ──────────────────────────────────────────────────

print("\n=== Customer Segment Distribution ===")

segment_stats = customers.groupby('segment').agg(

count = ('customer_id', 'count'),

avg_spend = ('total_spend', 'mean'),

avg_orders = ('total_orders', 'mean'),

avg_recency_days = ('days_since_purchase','mean'),

subscription_pct = ('has_subscription', 'mean')

).round(2)

segment_stats['count_pct'] = (segment_stats['count'] / len(customers) * 100).round(1)

segment_stats = segment_stats.sort_values('avg_spend', ascending=False)

print(segment_stats)

print("\n=== Segment Counts ===")

print(customers['segment'].value_counts())This pipeline demonstrates apply() used for three distinct purposes: data cleaning (phone standardization), feature engineering (RFM metrics), and business logic (segment assignment) — covering the full range of real-world apply() use cases in a single coherent workflow.

Conclusion: apply() Is Your Swiss Army Knife for Custom Transformations

The Pandas apply() function occupies a unique and essential position in the data science toolkit. It is not the fastest tool — vectorized NumPy operations, .str methods, and np.select() are all faster for operations they can express. But apply() is the most flexible tool, capable of running any arbitrary Python logic across your data’s rows, columns, or elements.

In this article, you learned the core mental model: apply() on a Series is element-wise, apply() on a DataFrame with axis=0 is column-wise, and apply() with axis=1 is row-wise. You learned to use lambda functions for concise inline transformations and named functions for complex logic. You explored map() for Series lookups and value substitution, and DataFrame.map() for element-wise DataFrame transformations. You saw practical examples ranging from phone number cleaning to risk scoring to text feature extraction, and you built a complete customer segmentation pipeline.

Most importantly, you learned when not to use apply() — recognizing that vectorized operations are dramatically faster and should always be your first choice. Apply apply() when the logic genuinely requires it: complex multi-column conditional logic, external library calls, or custom aggregations in GroupBy operations.

With apply() in your toolkit alongside the Pandas fundamentals you have built through this series — Series, DataFrames, missing data handling, groupby aggregation, and merging — you now have the complete foundation for professional-grade data manipulation in Python.

Key Takeaways

apply()on a Series calls your function once per element; on a DataFrame withaxis=0once per column; withaxis=1once per row.- Lambda functions are ideal for simple one-liner transformations; named functions are better for complex logic that deserves documentation.

- Pass additional arguments to your function via

args=(value,)(tuple) or keyword arguments directly in theapply()call. - When your function returns a

pd.Series, the result is automatically expanded into multiple columns — a powerful pattern for generating several new features at once. Series.map()is faster thanSeries.apply()for element-wise operations and also accepts dictionaries for value lookup/substitution.DataFrame.map()(formerlyapplymap()) applies a function to every individual cell in a DataFrame.- Row-wise

apply(axis=1)is the slowest Pandas operation — always check if a vectorized alternative exists usingnp.select(),pd.cut(), arithmetic operators, or.strmethods. - Always handle

NaNvalues explicitly inside yourapply()functions to avoid unexpected errors or silent incorrect results. - Test your function on a single row with

df.iloc[0]before applying it to the entire DataFrame. groupby().apply()passes each group’s full sub-DataFrame to your function, enabling powerful custom group-level aggregations beyond whatagg()supports.