Beyond the Generic Job Title

When you search for data scientist positions on job boards, you encounter hundreds of openings with remarkably similar titles but wildly different job descriptions. One company seeks a data scientist to build recommendation systems using deep learning. Another wants someone to create dashboards and analyze A/B tests. A third needs a data scientist to build data pipelines and maintain infrastructure. They all use the same title, yet these jobs require different skills, involve different daily activities, and appeal to people with different interests.

This confusion stems from the fact that “data scientist” has become an umbrella term covering multiple distinct roles that happen to involve working with data. Understanding these different types helps you target your learning toward the specific skills you will actually use, evaluate job opportunities more accurately, and build a career aligned with your strengths and interests rather than chasing a generic title that means different things to different employers.

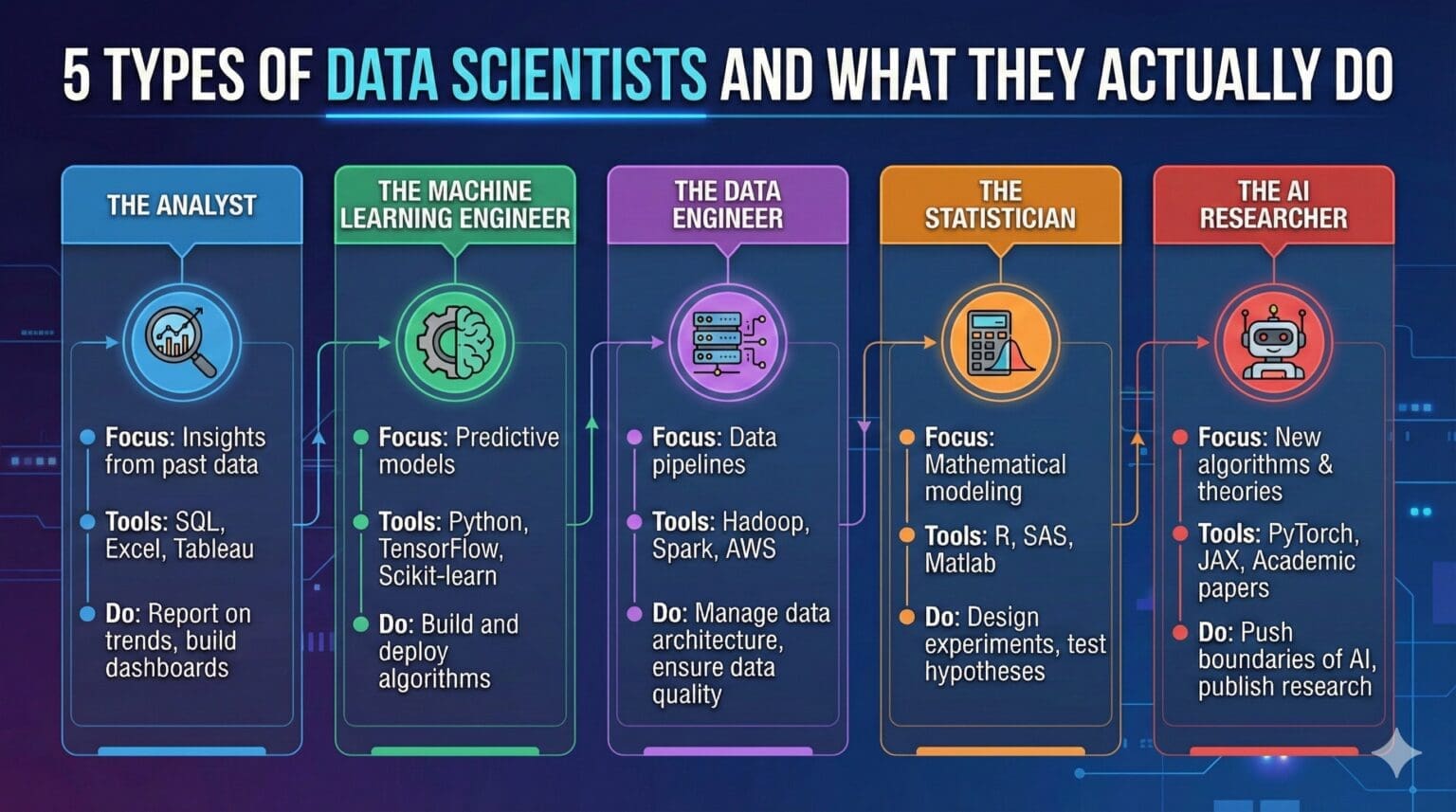

The data science field has matured enough that specializations have emerged, each focusing on different aspects of the work. While individual jobs often blend elements from multiple types, recognizing these archetypes provides clarity about the landscape. Let me walk you through the five main types of data scientists you will encounter, explaining what each actually does, what skills they emphasize, and what kind of person tends to thrive in each role.

The Analytics-Focused Data Scientist: Answering Business Questions

Analytics-focused data scientists spend their time helping organizations understand their business through data-driven insights. They answer questions like why sales dropped last quarter, which customer segments show the strongest growth, what factors influence product adoption, or how different marketing channels compare in effectiveness. Their work emphasizes exploration, interpretation, and communication more than building production systems or developing novel algorithms.

A typical day for an analytics-focused data scientist involves a mix of activities centered around investigation and explanation. They might start by meeting with product managers who want to understand why a new feature is not being used as expected. The data scientist would pull usage data, segment it by user characteristics, compare adoption patterns across different user groups, and create visualizations showing where the feature is succeeding or struggling. They would then present findings back to the product team with recommendations based on the data.

Throughout the day, they field ad-hoc questions from stakeholders across the organization. A marketing manager wants to know which email campaign performed best. A sales leader needs analysis of win rates by region. An executive asks about trends in customer complaints. The analytics-focused data scientist must quickly understand what question is really being asked, determine what data can address it, perform appropriate analysis, and communicate results clearly to non-technical audiences.

They also own recurring analytical work like monthly business reviews, cohort analyses tracking user behavior over time, and deep dives into specific metrics when unusual patterns appear. Much of their analysis uses established statistical methods rather than cutting-edge machine learning. Linear regression, hypothesis testing, segmentation, and trend analysis form their core toolkit. They might build simple predictive models to forecast demand or identify customer churn risk, but complex machine learning is not their primary focus.

The skill set emphasizes practical statistics, data manipulation, visualization, and communication. Analytics-focused data scientists must be fluent in SQL for extracting data from databases and proficient in Python or R for analysis and visualization. They need solid understanding of experimental design to properly evaluate A/B tests. They excel at choosing appropriate statistical methods for different types of questions and explaining technical concepts to business audiences.

Crucially, they develop deep domain knowledge in the business they support. An analytics-focused data scientist working in e-commerce understands customer journey stages, conversion funnel metrics, and retention dynamics. Someone in finance knows accounting principles, regulatory requirements, and risk metrics. This business acumen helps them ask better questions, interpret findings correctly, and provide recommendations that account for business realities beyond what data alone reveals.

People who thrive in analytics-focused roles enjoy variety in their daily work, as different questions arise constantly. They like the immediate impact of providing insights that stakeholders use to make decisions. They appreciate working closely with business partners and developing expertise in specific domains. They value communication and influencing through data more than building complex technical systems. If you enjoy being a business partner who happens to use data rather than primarily a technologist, this path might suit you.

Career progression typically moves from junior analyst roles handling routine reporting and simple analyses, through mid-level positions owning specific analytical domains or product areas, to senior or lead analyst roles defining analytical strategy and mentoring others. Some analytics-focused data scientists transition into product management or business strategy roles where their analytical skills combine with broader business responsibilities.

The Machine Learning Specialist: Building Intelligent Systems

Machine learning specialists focus on developing predictive models and intelligent systems that can learn from data and make automated decisions. They build recommendation engines that suggest products users might like, fraud detection systems that flag suspicious transactions, computer vision models that identify objects in images, or natural language processing systems that understand text. Their work emphasizes algorithm selection, model optimization, and creating systems that perform well on new data they have not seen before.

Daily work for machine learning specialists involves substantial experimentation and iteration. They might spend a morning researching different approaches to a computer vision problem, reading recent papers to understand state-of-the-art techniques. The afternoon could involve implementing a new model architecture, training it on their data, and evaluating whether it outperforms existing approaches. They run many experiments, carefully tracking what works and what does not, gradually improving performance through systematic testing.

They work extensively with labeled training data, understanding that model quality depends heavily on data quality and quantity. They might spend time improving data labeling processes, creating tools to make labeling more efficient, or developing active learning strategies to identify which examples would be most valuable to label. They think carefully about how to split data into training, validation, and test sets to properly evaluate model performance.

Feature engineering consumes significant time as they transform raw data into representations that models can learn from effectively. For a text classification task, this might involve comparing bag-of-words approaches against word embeddings, testing different text preprocessing strategies, or creating custom features based on domain knowledge. They constantly ask what information the model needs to make accurate predictions and how to provide that information most effectively.

Model evaluation goes beyond simple accuracy metrics. They examine confusion matrices to understand error patterns, calculate precision and recall for different classes, analyze performance across different data segments to ensure fairness, and use techniques like cross-validation to estimate real-world performance. They are intimately familiar with the tradeoffs between different evaluation metrics and which metrics matter most for their specific use case.

The technical skill set leans heavily on programming, mathematics, and machine learning theory. Machine learning specialists need strong Python or R skills with deep knowledge of libraries like scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch. They understand the mathematical foundations of algorithms including linear algebra, calculus, probability, and optimization. They stay current with machine learning research, reading papers and experimenting with new techniques. They often have graduate degrees in computer science, statistics, or related quantitative fields.

However, technical skills alone are insufficient. Successful machine learning specialists also understand the business problems they are solving and the constraints within which their models must operate. A model that takes ten seconds to make a prediction might be useless if the application needs results in milliseconds. A model with ninety-five percent accuracy might fail if the five percent of errors concentrate in critical scenarios. Balancing technical sophistication with practical requirements requires business understanding alongside technical expertise.

People drawn to machine learning specialist roles enjoy solving complex technical problems that require deep thinking and experimentation. They like staying at the cutting edge of technology and applying novel techniques to real problems. They appreciate the intellectual challenge of understanding why models behave in certain ways and how to improve them. They are comfortable with ambiguity and the reality that many experiments fail before finding approaches that work. If you love the science in data science and want to focus primarily on building intelligent systems, this specialization suits you.

Career paths often start with junior machine learning engineer or data scientist roles working on well-defined problems with guidance from senior team members. Mid-level positions involve greater autonomy and tackling more challenging problems. Senior machine learning scientists or engineers lead projects, define technical approaches, and contribute to research. Some move into research scientist roles focusing primarily on advancing the state of the art, while others transition toward engineering management.

The Data Engineer: Building the Foundation

Data engineers create and maintain the infrastructure that makes data science possible. While they might not perform as much analysis or build as many models as other data scientist types, they ensure that data flows reliably from source systems to databases where analysts and machine learning specialists can access it. Without data engineers, other data scientists would drown in the complexity of extracting, transforming, and loading data rather than focusing on extracting insights.

Their daily work centers on building and maintaining data pipelines that move information through systems. They might design a pipeline that extracts customer transaction data from a production database every hour, transforms it by cleaning inconsistencies and calculating aggregated metrics, and loads it into a data warehouse where analysts can query it. They ensure these pipelines run reliably, handle errors gracefully, and scale to accommodate growing data volumes.

Data quality obsesses data engineers because downstream analyses and models depend entirely on reliable data. They build validation checks that detect anomalies, create monitoring systems that alert when data pipelines fail or produce unexpected results, and develop processes for investigating and fixing data quality issues. They think systematically about how data errors propagate through pipelines and design systems to catch problems early.

They work extensively with databases, both traditional relational databases and modern big data technologies. They need to understand when to use different types of databases, how to optimize query performance, how to partition data for efficient access, and how to ensure data consistency and reliability. They might set up and maintain data warehouses using tools like Snowflake or BigQuery, implement streaming data platforms using Kafka, or manage large-scale data processing with Spark.

Data modeling represents another core responsibility. They design schemas that organize data logically, create dimension and fact tables for analytical queries, and build data marts tailored to specific business needs. Good data modeling makes subsequent analysis dramatically easier by organizing information intuitively and optimizing it for common query patterns.

The skill set emphasizes software engineering more than other data science specializations. Data engineers need strong programming abilities in languages like Python, Java, or Scala. They must understand distributed systems, as modern data often exceeds what single machines can handle. They work with cloud platforms like AWS, Google Cloud, or Azure, knowing how to leverage cloud services for data storage and processing. They use version control, write tests, and follow software development best practices.

SQL mastery is absolutely essential, as querying and transforming data in databases consumes much of their time. They write complex queries involving multiple joins, window functions, and subqueries. They optimize slow queries and design efficient data structures. They often know SQL more deeply than other data scientist types because it forms such a large part of their daily work.

While data engineers might not build as many machine learning models, they increasingly work closely with machine learning specialists to deploy models to production. They create systems that serve model predictions at scale, build pipelines that retrain models on new data, and implement monitoring to detect when model performance degrades. This collaboration between data engineers and machine learning specialists ensures models transition from research projects to production systems.

People who excel as data engineers enjoy building systems and infrastructure more than performing analyses or building models. They appreciate the engineering challenges of making systems reliable, scalable, and efficient. They like solving technical problems and take pride in creating foundations that others build upon. They are comfortable working behind the scenes enabling others rather than directly answering business questions. If you have software engineering inclinations and want to work with data but do not necessarily want to focus on statistics or machine learning, data engineering might be your path.

Career progression often starts with junior data engineer or ETL developer roles learning to build basic pipelines. Mid-level data engineers own larger portions of data infrastructure and tackle more complex challenges. Senior data engineers and data architects design entire data platforms and set technical direction. Some move into engineering management while others become specialized experts in particular technologies or domains.

The Research Data Scientist: Advancing the Field

Research data scientists focus on developing new methods and pushing the boundaries of what is possible with data rather than applying existing techniques to business problems. They work primarily in academic settings, research labs, or the research divisions of large technology companies. While they still solve problems, their problems often involve creating new algorithms, proving mathematical properties of methods, or publishing findings that advance the field’s collective knowledge.

Their daily work looks quite different from other data scientist types. They might spend mornings reading recent academic papers to understand current research directions and identify gaps in existing knowledge. Afternoons could involve mathematical derivations proving properties of proposed algorithms, implementing new methods to test theoretical ideas, or running extensive experiments comparing their approach against existing techniques. Writing consumes substantial time, as they must document their work clearly for peer review and publication.

Research data scientists tackle questions that do not have obvious answers. Can we develop algorithms that learn effectively with very little labeled data? How can we make models more interpretable without sacrificing accuracy? What theoretical guarantees can we provide about when certain methods will work? Can we create models that generalize better across different domains? These questions require deep thinking, mathematical rigor, and willingness to explore ideas that might not pan out.

Publishing their work in academic conferences and journals represents a key measure of success. They must not only develop novel ideas but communicate them clearly to the research community, responding to peer review feedback and defending their contributions. The publication process can take many months from initial submission to acceptance, requiring patience and persistence. Citations and recognition from other researchers matter more than immediate business impact.

Collaboration takes different forms than in industry settings. Research data scientists often work with other researchers, combining complementary expertise to tackle complex problems. They might collaborate with domain experts in fields like biology or physics to apply machine learning to scientific problems. They supervise graduate students who contribute to research projects while learning from the experience. These collaborations can span institutions and countries, united by shared research interests.

The skill set heavily emphasizes mathematics and theoretical foundations. Research data scientists need deep understanding of statistics, optimization theory, information theory, and the mathematical underpinnings of machine learning algorithms. They must be comfortable with mathematical proofs and rigorous analysis. Programming remains important for implementing and testing ideas, but the emphasis is more on experimental validation of theories than production-quality code. They stay deeply current with academic literature and contribute to it regularly.

Domain expertise varies depending on their research focus. Someone researching computer vision needs to understand image processing and related signal processing theory. A researcher focused on natural language processing must know linguistics and language structure. Those working on applications in specific fields like healthcare or finance develop expertise in those domains. This specialized knowledge helps them identify important problems and develop methods that address real constraints.

People drawn to research data scientist roles love the intellectual challenge of advancing knowledge and solving problems nobody has solved before. They enjoy the freedom to pursue interesting questions even when practical applications are not immediate. They value the academic culture of open inquiry, peer review, and building on others’ work. They are comfortable with uncertainty and the reality that many research directions do not produce publishable results. If you want to push the boundaries of the field and contribute to human knowledge more than solving immediate business problems, research might be your calling.

Career progression in research typically involves earning a PhD in a relevant field, then either pursuing academic careers as professors or joining industrial research labs. Academic paths involve progressing from postdoctoral positions through assistant professor to tenured faculty roles, with expectations of securing research funding and publishing regularly. Industrial research scientists face different pressures but still focus primarily on advancing the state of the art rather than shipping products.

The Full-Stack Data Scientist: Wearing Multiple Hats

Full-stack data scientists handle the entire pipeline from data collection through model deployment themselves rather than specializing in one area. They might design an experiment, collect and clean the data, build and evaluate models, and deploy them to production, owning the complete process. This role appears more commonly in startups and smaller companies that cannot afford separate specialists for each function, but some individuals simply prefer the variety and ownership of handling everything.

Daily work involves rapidly switching between different types of tasks. A morning might involve meeting with stakeholders to define requirements for a new predictive model, afternoon could be spent building the data pipeline to support it, and evening might involve actually training and evaluating models. The next day might focus on deploying the model to production and creating a dashboard for stakeholders to monitor its predictions. This variety keeps work interesting but also demands versatility across many skill areas.

Full-stack data scientists need to be generalists with enough skill in each area to handle common tasks independently. They write SQL to extract data, build ETL pipelines to clean and prepare it, perform exploratory analysis to understand patterns, engineer features, train machine learning models, evaluate performance, deploy to production, and create visualizations or dashboards to communicate results. They might not have the deep expertise of specialists in any single area, but they understand enough about each to avoid major mistakes.

This breadth comes with tradeoffs. Full-stack data scientists can move quickly because they do not need to coordinate with multiple specialists or wait for other teams. They understand the entire context of projects because they own every phase. They can make design decisions that optimize the complete system rather than just their piece. However, they might struggle with the most complex problems in any single area that would benefit from specialist expertise. They must consciously invest in staying current across multiple domains rather than going deep in one.

The skill set combines elements from all other types. Programming ability is essential, as full-stack data scientists write substantial code for every phase from data processing through model deployment. They need working knowledge of databases, data pipelines, statistical methods, machine learning algorithms, and production systems. They benefit from strong problem-solving abilities that help them figure out unfamiliar areas independently, as they cannot rely on specialists when they encounter new challenges. Time management and prioritization matter greatly given the breadth of responsibilities.

Business acumen becomes particularly important because full-stack data scientists often work directly with stakeholders without layers of specialization in between. They must understand business problems well enough to define appropriate technical approaches, manage expectations about what is possible, and deliver solutions that create genuine value rather than impressive-but-useless technical demonstrations. They bridge business and technical worlds constantly.

People who thrive as full-stack data scientists enjoy variety and autonomy. They like owning problems completely rather than handing off pieces to other specialists. They appreciate the challenge of learning enough about many areas to be effective across the board. They value the ability to move quickly and iterate without coordination overhead. They are comfortable being generalists rather than deep experts. If you get bored focusing on just one aspect of data work and want to own entire projects yourself, the full-stack path might suit you.

Career progression is less standardized than for specialized roles. In startups, you might start as the only data person and grow into leading a team as the company scales. In larger companies, full-stack roles might not exist formally, but you could create this career by intentionally building breadth across multiple specializations. Some full-stack data scientists transition into product management or leadership roles where their broad understanding of the entire data pipeline proves valuable. Others specialize over time as they discover which aspects they enjoy most.

Choosing Your Specialization Based on Your Strengths

Understanding these different types of data scientists helps you make informed decisions about which direction to pursue. Rather than trying to master everything, you can focus your learning on skills that match your interests and natural strengths.

If you enjoy answering questions and influencing decisions through analysis, the analytics-focused path leverages those strengths. If complex technical challenges and algorithms excite you, machine learning specialist roles provide depth in those areas. If you have software engineering background and like building reliable systems, data engineering plays to those skills. If you want to advance human knowledge through research, the research scientist path channels that motivation. If you prefer variety and ownership, full-stack roles offer that flexibility.

Your educational background might also influence which path is most accessible. Analytics-focused roles often accept candidates from diverse backgrounds including business, social sciences, or self-taught paths. Machine learning specialist and research positions typically prefer computer science or statistics degrees, often at the graduate level. Data engineering roles value computer science or software engineering backgrounds. Full-stack positions might accept anyone who can demonstrate broad capability regardless of formal credentials.

The industry and company you target matters as well. Large technology companies often have all five types with clear specialization. Consulting firms might emphasize analytics-focused data scientists who work directly with clients. Startups often need full-stack data scientists who can handle everything. Academic institutions and research labs employ research data scientists. Understanding where each type thrives helps you target your job search effectively.

Remember that specializations are not permanent prisons. Many successful data scientists have worked across multiple types during their careers, perhaps starting in analytics to build business understanding, moving into machine learning as they develop those skills, or transitioning to data engineering to focus on infrastructure. The skills you build in one specialization often transfer to others, even if the emphasis differs. Choosing one path now does not prevent you from evolving later.

The Future of Data Science Specializations

As the field continues maturing, we will likely see further specialization and the emergence of new distinct roles. Already we see specializations within machine learning like computer vision experts, natural language processing specialists, or reinforcement learning researchers. Similarly, data engineering is fragmenting into roles like analytics engineers, machine learning engineers, and data platform engineers, each with slightly different focuses.

At the same time, some convergence is happening as tools improve and best practices spread. Automated machine learning tools make sophisticated modeling accessible to analytics-focused data scientists who might not have deep machine learning expertise. Modern data platforms simplify pipeline creation, reducing the need for specialized data engineering for simpler use cases. This dual trend of specialization in complex areas and democratization of basic capabilities will likely continue.

The key is building strong fundamentals that serve you across specializations while developing deeper expertise in areas that match your interests. Understanding statistics, programming, and how to think about data problems provides a foundation for any type of data science work. From that base, you can specialize as opportunities and interests dictate.

Conclusion

The “data scientist” title encompasses at least five distinct types of work: analytics-focused data scientists who answer business questions, machine learning specialists who build intelligent systems, data engineers who create data infrastructure, research data scientists who advance the field, and full-stack data scientists who handle everything themselves. Each type involves different daily work, emphasizes different skills, and appeals to different personalities and interests.

Understanding these distinctions helps you target your learning toward skills you will actually use, evaluate job opportunities more accurately, and build a career aligned with your strengths rather than chasing a generic title. The data science field is broad enough to accommodate many different types of people and working styles, but success requires matching your path to your particular combination of interests and abilities.

Rather than trying to be equally good at everything, identify which type of work energizes you and develop the specific skills that area requires. Build strong fundamentals that serve you across specializations, then develop expertise in areas that match your interests and goals. The most successful data scientists are not necessarily those who know the most overall, but those who develop deep expertise in areas that create value and that they genuinely enjoy.

In the next article, we will explore the essential skills every data scientist needs regardless of specialization, covering the foundational knowledge that supports all types of data science work. This will help you understand what to focus on first as you build your capabilities and what continues to matter throughout your career.

Key Takeaways

Data scientist roles vary significantly despite using the same title, with at least five distinct types each requiring different skills and involving different work. Analytics-focused data scientists answer business questions using data, emphasizing statistical analysis, visualization, and communication with stakeholders. Machine learning specialists build predictive models and intelligent systems, focusing on algorithms, optimization, and creating systems that learn from data.

Data engineers create the infrastructure that makes data science possible, building pipelines, ensuring data quality, and designing databases that store and serve data efficiently. Research data scientists advance the field by developing new methods, publishing academic papers, and solving problems nobody has solved before. Full-stack data scientists handle everything themselves from data collection through deployment, trading specialization for breadth and autonomy.

Choosing your specialization should consider what type of work energizes you, what skills you enjoy developing, your educational background, and what kind of organizations you want to work for. The boundaries between these types are permeable, and many successful data scientists work across multiple specializations during their careers.

Understanding these different types helps you focus your learning on relevant skills, evaluate job opportunities accurately, and build a career path aligned with your interests and strengths rather than pursuing a generic title that means different things to different employers.