Introduction: Why Pandas is Essential for Machine Learning

Real-world machine learning projects spend 60-80% of their time on data preparation, not model building. This surprising statistic reveals a fundamental truth: the quality of your machine learning models depends heavily on the quality and preparation of your data. Pandas is the library that makes this critical data preparation phase manageable, efficient, and even enjoyable.

Before Pandas existed, Python programmers manipulated data using nested loops, dictionaries of lists, and custom data structures. This approach was tedious, error-prone, and slow. Pandas changed everything by introducing high-level data structures specifically designed for data analysis, along with intuitive methods for common data manipulation tasks. It bridges the gap between raw data files and the clean, processed datasets that machine learning algorithms require.

Think of Pandas as the Swiss Army knife of data manipulation. Need to load a CSV file with millions of rows? Pandas does it in one line. Need to remove rows with missing values? One method call. Need to compute statistics grouped by categories? Pandas makes it trivial. Need to merge datasets from different sources? Pandas handles it elegantly. These operations that would require dozens or hundreds of lines of pure Python code become simple, readable statements with Pandas.

The library’s name comes from “panel data,” an econometrics term for multi-dimensional datasets. While originally designed for financial data analysis, Pandas has become the standard tool for all data manipulation in Python. Every data scientist, machine learning engineer, and AI researcher uses Pandas daily. Learning Pandas is not optional—it’s fundamental to working with data in Python.

This comprehensive guide will transform you from a Pandas beginner into a confident data manipulator. We’ll start by understanding DataFrames and Series, the core data structures. We’ll explore loading data from various sources and examining it to understand its characteristics. We’ll master data selection and filtering to extract exactly the information we need. We’ll learn data cleaning techniques to handle the messy reality of real-world data. We’ll discover powerful grouping and aggregation operations for analyzing patterns. We’ll explore joining and merging datasets from multiple sources. Throughout, we’ll connect each operation to practical machine learning scenarios, ensuring you understand not just the syntax but the real-world applications.

Understanding DataFrames and Series: Pandas’ Core Structures

Before diving into data manipulation operations, you must understand Pandas’ two fundamental data structures: Series and DataFrames. These structures are the foundation of everything you do in Pandas, and comprehending them deeply makes everything else easier.

Series: One-Dimensional Labeled Arrays

A Series is Pandas’ one-dimensional data structure. Think of it as a column in a spreadsheet or a single variable in a dataset. What makes a Series different from a NumPy array or Python list is that each value has an associated label called an index. This index lets you access values by meaningful names rather than just numeric positions.

Consider recording daily temperatures for a week. With a regular list, you’d access values by position: temperatures[0] for the first day. With a Series, you can use meaningful labels: temperatures['Monday']. This labeling makes your code more readable and less error-prone, especially when working with time series or data with natural labels.

Each Series has a data type (dtype) that applies to all its values. This uniformity enables efficient storage and fast operations. A Series of integers uses much less memory than a Python list containing the same numbers because the Series stores them compactly without Python’s object overhead.

DataFrames: Two-Dimensional Labeled Data

A DataFrame is a two-dimensional table with labeled rows and columns. If you’ve worked with spreadsheets, SQL tables, or R data frames, you’ll find DataFrames familiar. Each column in a DataFrame is a Series, meaning columns can have different data types while sharing the same row index.

DataFrames are perfect for representing real-world datasets. Consider customer data: one column might contain customer IDs (integers), another names (strings), another ages (integers), and another purchase amounts (floats). Each row represents a customer, and columns represent different attributes. This structure naturally matches how we think about tabular data.

The row index and column names make DataFrames powerful. You can select specific rows by their labels, specific columns by name, or combinations of both. This labeled selection is more robust than numeric indexing—if you add or remove columns, your code referencing columns by name continues working, while code using numeric positions breaks.

Let’s see these structures in action and understand their properties:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Creating a Series - representing a single variable

# Example: accuracy scores from different model runs

accuracies = pd.Series([0.85, 0.89, 0.92, 0.88, 0.91],

index=['run_1', 'run_2', 'run_3', 'run_4', 'run_5'],

name='accuracy')

print("Series Example: Model Accuracy Scores")

print("=" * 60)

print(accuracies)

print()

print(f"Data type: {accuracies.dtype}")

print(f"Shape: {accuracies.shape}")

print(f"Number of elements: {len(accuracies)}")

print()

# Accessing Series elements

print("Accessing Series values:")

print(f" By label: accuracies['run_3'] = {accuracies['run_3']}")

print(f" By position: accuracies[2] = {accuracies[2]}")

print(f" Multiple values: {accuracies[['run_1', 'run_5']].tolist()}")

print()

# Series operations

print("Series statistics:")

print(f" Mean: {accuracies.mean():.4f}")

print(f" Median: {accuracies.median():.4f}")

print(f" Std: {accuracies.std():.4f}")

print(f" Max: {accuracies.max():.4f}")

print()

# Creating a DataFrame - representing multiple variables

# Example: customer data for churn prediction

data = {

'customer_id': [101, 102, 103, 104, 105],

'age': [25, 35, 28, 42, 31],

'monthly_spend': [120.50, 85.30, 200.75, 150.00, 95.80],

'months_active': [12, 24, 6, 36, 18],

'will_churn': [0, 0, 1, 0, 1] # Target variable: 0=stay, 1=leave

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print("DataFrame Example: Customer Churn Data")

print("=" * 60)

print(df)

print()

# DataFrame properties

print("DataFrame information:")

print(f" Shape (rows, columns): {df.shape}")

print(f" Number of rows: {len(df)}")

print(f" Number of columns: {len(df.columns)}")

print(f" Column names: {df.columns.tolist()}")

print(f" Index: {df.index.tolist()}")

print()

# Data types of each column

print("Column data types:")

print(df.dtypes)

print()

# Quick statistics summary

print("Statistical summary:")

print(df.describe())What this code demonstrates: This example introduces both Series and DataFrames through practical machine learning scenarios. The Series represents accuracy scores from model runs, showing how labels make data more meaningful than position-based indexing. The DataFrame represents a customer dataset for churn prediction, demonstrating how different data types coexist in columns while sharing the same row index. We examine properties like shape, dtypes, and indices that help us understand our data’s structure. The describe() method provides instant statistical summaries, a crucial first step in data exploration.

Understanding these data structures is fundamental because every Pandas operation works with Series or DataFrames. When you select a column from a DataFrame, you get a Series. When you filter rows, you get a DataFrame. This consistency makes Pandas intuitive once you grasp these core structures.

Loading Data: Bringing Data into Pandas

Machine learning projects start with loading data from external sources. Data rarely comes pre-loaded in Python—it lives in files, databases, or APIs. Pandas excels at reading data from diverse formats, transforming files into DataFrames ready for analysis.

CSV Files: The Most Common Format

CSV (Comma-Separated Values) files are the lingua franca of data exchange. They’re simple text files where each line represents a row and commas separate columns. Despite their simplicity, CSV files can contain millions of rows and represent complex datasets. Pandas’ read_csv() function is remarkably powerful, handling various CSV dialects, encoding issues, and data type inference automatically.

Other Common Formats

Beyond CSV, Pandas reads Excel files (read_excel()), JSON data (read_json()), SQL databases (read_sql()), and many other formats. Each format has specific parameters to handle its peculiarities, but the general pattern remains consistent: call the appropriate read function, get a DataFrame.

Data Loading Best Practices

When loading data, always inspect it immediately. Check the shape to see how many rows and columns loaded. Examine the first few rows with head() to verify columns imported correctly. Check data types with dtypes to ensure numerical columns aren’t interpreted as strings. Look for missing values with isnull().sum(). These quick checks catch common loading issues before they cause problems later.

Let’s explore loading data and initial inspection:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Since we can't load actual files in this demonstration,

# we'll create synthetic data that represents what you'd get from loading files

# Simulating CSV file loading

# In practice: df = pd.read_csv('customer_data.csv')

print("Loading Data Example")

print("=" * 60)

print()

# Create sample data simulating a loaded dataset

# This represents customer information with some real-world messiness

np.random.seed(42)

n_customers = 100

customer_data = {

'customer_id': range(1000, 1000 + n_customers),

'signup_date': pd.date_range('2023-01-01', periods=n_customers, freq='D'),

'age': np.random.randint(18, 70, n_customers),

'income': np.random.randint(30000, 150000, n_customers),

'purchase_count': np.random.randint(1, 50, n_customers),

'total_spent': np.random.uniform(100, 5000, n_customers),

'account_type': np.random.choice(['basic', 'premium', 'enterprise'], n_customers),

'region': np.random.choice(['North', 'South', 'East', 'West'], n_customers)

}

df = pd.DataFrame(customer_data)

# Add some missing values to simulate real-world data

missing_indices = np.random.choice(df.index, size=10, replace=False)

df.loc[missing_indices[:5], 'income'] = np.nan

df.loc[missing_indices[5:], 'purchase_count'] = np.nan

print("Step 1: Initial Data Inspection")

print("-" * 60)

print("\nFirst 5 rows (head):")

print(df.head())

print()

print("Last 3 rows (tail):")

print(df.tail(3))

print()

print("\nStep 2: Understanding Data Structure")

print("-" * 60)

print(f"Dataset shape: {df.shape[0]} rows × {df.shape[1]} columns")

print(f"\nColumn names and types:")

print(df.dtypes)

print()

print("\nStep 3: Memory Usage")

print("-" * 60)

memory_usage = df.memory_usage(deep=True)

print(f"Total memory: {memory_usage.sum() / 1024:.2f} KB")

print("\nMemory per column:")

print(memory_usage)

print()

print("\nStep 4: Missing Values Check")

print("-" * 60)

missing_counts = df.isnull().sum()

missing_pct = (missing_counts / len(df) * 100).round(2)

missing_summary = pd.DataFrame({

'Missing Count': missing_counts,

'Percentage': missing_pct

})

print(missing_summary[missing_summary['Missing Count'] > 0])

print()

print("\nStep 5: Statistical Summary")

print("-" * 60)

print(df.describe())

print()

print("\nStep 6: Unique Values in Categorical Columns")

print("-" * 60)

categorical_cols = ['account_type', 'region']

for col in categorical_cols:

unique_values = df[col].unique()

value_counts = df[col].value_counts()

print(f"\n{col}:")

print(f" Unique values: {unique_values}")

print(f" Distribution:\n{value_counts}")

print()

print("\nStep 7: Data Quality Issues to Address")

print("-" * 60)

print(f"✓ Missing values detected in {missing_counts[missing_counts > 0].count()} columns")

print(f"✓ Date column needs to be verified as datetime type")

print(f"✓ Numerical columns look reasonable (no extreme outliers visible)")

print(f"✓ Categorical columns have expected values")What this code demonstrates: This example walks through a systematic data loading and inspection process. After loading (simulated here, but identical to loading from files), we immediately inspect the first and last rows to verify the data loaded correctly. We check the shape to understand dataset size. We examine data types to ensure columns were interpreted correctly. We assess memory usage, which matters for large datasets. We identify missing values, a critical data quality issue. We generate statistical summaries to understand distributions and detect potential outliers. We examine unique values in categorical columns to verify data integrity.

This inspection process should become automatic. Every time you load data, perform these checks. They take seconds but prevent hours of debugging later when you discover your model trained on incorrectly loaded or dirty data.

Selecting and Filtering Data: Extracting What You Need

Once data is loaded, you need to extract specific subsets for analysis. Pandas provides multiple ways to select data, each suited to different situations. Understanding when to use each method makes you efficient and prevents common errors.

Column Selection: Getting Features

The simplest selection is choosing columns. For machine learning, you often need to separate features from target variables or select specific feature subsets. Pandas offers bracket notation (df['column']) for single columns and double brackets (df[['col1', 'col2']]) for multiple columns.

Single bracket selection returns a Series—a one-dimensional structure. Double bracket selection returns a DataFrame—a two-dimensional structure even if selecting just one column. This distinction matters when chaining operations or passing data to functions expecting specific types.

Row Selection: Filtering Samples

Selecting rows based on conditions is fundamental to data filtering. You might want training samples from a specific time period, customers from a particular region, or transactions above a threshold. Pandas supports boolean indexing: create a boolean Series indicating which rows meet your criteria, then use it to filter the DataFrame.

Combined Selection: Rows and Columns Together

Often you need specific rows AND specific columns. Pandas provides loc[] for label-based selection and iloc[] for position-based selection. Understanding the difference is crucial: loc[] uses column names and row labels, while iloc[] uses integer positions. For most machine learning work, loc[] is preferable because it’s more robust—column names don’t change even if column order does.

Let’s explore these selection techniques:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Create sample dataset

np.random.seed(42)

df = pd.DataFrame({

'customer_id': range(1, 11),

'age': [25, 35, 28, 42, 31, 29, 38, 26, 45, 33],

'income': [45000, 75000, 52000, 88000, 62000, 48000, 71000, 50000, 92000, 65000],

'purchases': [5, 12, 7, 18, 10, 6, 15, 8, 20, 11],

'region': ['North', 'South', 'East', 'North', 'West', 'South', 'East', 'North', 'West', 'South'],

'premium': [False, True, False, True, True, False, True, False, True, True]

})

print("Original Dataset")

print("=" * 60)

print(df)

print()

# ==================================================================

# COLUMN SELECTION

# ==================================================================

print("1. SELECTING COLUMNS")

print("-" * 60)

# Single column - returns Series

age_series = df['age']

print("Single column (Series):")

print(f"Type: {type(age_series)}")

print(f"Shape: {age_series.shape}")

print(age_series.head())

print()

# Multiple columns - returns DataFrame

features = df[['age', 'income', 'purchases']]

print("Multiple columns (DataFrame):")

print(f"Type: {type(features)}")

print(f"Shape: {features.shape}")

print(features.head())

print()

# Selecting all columns except some

all_except_id = df.drop('customer_id', axis=1)

print("All columns except customer_id:")

print(all_except_id.head(3))

print()

# ==================================================================

# ROW FILTERING

# ==================================================================

print("\n2. FILTERING ROWS")

print("-" * 60)

# Simple condition: high income customers

high_income = df[df['income'] > 60000]

print("Customers with income > $60,000:")

print(high_income)

print()

# Multiple conditions: AND operator (&)

young_high_earners = df[(df['age'] < 35) & (df['income'] > 60000)]

print("Young (<35) high earners (>$60k):")

print(young_high_earners)

print()

# Multiple conditions: OR operator (|)

target_customers = df[(df['purchases'] > 15) | (df['premium'] == True)]

print("Customers with many purchases OR premium status:")

print(target_customers)

print()

# Using isin() for multiple values

northern_southern = df[df['region'].isin(['North', 'South'])]

print("Customers from North or South regions:")

print(northern_southern)

print()

# Negation: NOT operator (~)

not_premium = df[~df['premium']]

print("Non-premium customers:")

print(not_premium[['customer_id', 'premium']])

print()

# ==================================================================

# COMBINED SELECTION: ROWS AND COLUMNS

# ==================================================================

print("\n3. SELECTING ROWS AND COLUMNS TOGETHER")

print("-" * 60)

# Using loc[] - label-based

# Syntax: df.loc[row_selection, column_selection]

# Specific rows and columns

subset = df.loc[df['income'] > 70000, ['customer_id', 'age', 'income']]

print("High earners - selected columns only:")

print(subset)

print()

# All rows, specific columns

age_income = df.loc[:, ['age', 'income']]

print("Age and income for all customers (first 3):")

print(age_income.head(3))

print()

# Using iloc[] - position-based

# Syntax: df.iloc[row_positions, column_positions]

# First 5 rows, first 3 columns

subset_positional = df.iloc[:5, :3]

print("First 5 rows, first 3 columns:")

print(subset_positional)

print()

# Specific row and column positions

specific_cells = df.iloc[[0, 2, 4], [1, 3]] # Rows 0,2,4 and columns 1,3

print("Specific rows and columns by position:")

print(specific_cells)

print()

# ==================================================================

# PRACTICAL ML EXAMPLE: FEATURE AND TARGET SEPARATION

# ==================================================================

print("\n4. MACHINE LEARNING: SEPARATING FEATURES AND TARGET")

print("-" * 60)

# Add a target variable

df['will_purchase_again'] = (df['purchases'] > 10).astype(int)

# Select features (X) - all columns except target and ID

feature_columns = ['age', 'income', 'purchases', 'premium']

X = df[feature_columns]

# Select target (y)

y = df['will_purchase_again']

print(f"Features shape: {X.shape}")

print(f"Target shape: {y.shape}")

print("\nFeatures (first 3 samples):")

print(X.head(3))

print("\nTarget (first 10 values):")

print(y.head(10).tolist())

print()

# Filter to training samples (e.g., specific time period or region)

training_mask = df['region'].isin(['North', 'South'])

X_train = X[training_mask]

y_train = y[training_mask]

print(f"Training set size: {len(X_train)} samples")

print(f"Training class distribution: {y_train.value_counts().to_dict()}")What this code demonstrates: This comprehensive example shows the full spectrum of data selection techniques. We select single columns (returning Series) and multiple columns (returning DataFrames). We filter rows using boolean conditions with comparison operators. We combine multiple conditions using logical AND (&), OR (|), and NOT (~) operators. We use isin() for membership testing. We demonstrate loc[] for label-based selection and iloc[] for position-based selection, showing when each is appropriate. Finally, we show a practical machine learning pattern: separating features from targets and creating training subsets based on conditions.

Mastering these selection techniques is crucial because data manipulation consists largely of selecting the right subsets for different operations. Whether preprocessing features, analyzing segments, or preparing training data, you’re constantly selecting and filtering.

Data Cleaning: Handling Messy Real-World Data

Real-world data is messy. Files contain missing values, duplicates, inconsistent formatting, outliers, and errors. Machine learning algorithms require clean, consistent input. Data cleaning transforms messy reality into usable datasets. This unglamorous work consumes most of your time but determines your model’s success.

Missing Values: The Universal Challenge

Missing values appear in almost every real dataset. A customer might not provide their age. A sensor might fail to record a measurement. A survey respondent might skip a question. Missing values cause problems: many algorithms can’t handle them, and they might indicate important patterns (why is this value missing?).

Pandas represents missing values as NaN (Not a Number). You have several strategies for handling them: deletion (remove rows or columns with missing values), imputation (fill missing values with estimates like mean, median, or mode), forward/backward filling (use nearby values for time series), or predictive imputation (predict missing values using other features). The right choice depends on how much data is missing, why it’s missing, and your specific problem.

Duplicates: Redundant Information

Duplicate rows waste memory and can bias analysis. If the same customer appears three times, their preferences get triple-weighted. Finding and removing duplicates is straightforward with Pandas, but you must decide what constitutes a duplicate. Sometimes all columns must match; sometimes only certain identifying columns matter.

Data Type Issues: Getting Types Right

Columns might load with wrong types. Dates might be strings. Numeric values might include commas making them strings. Categories might be integers. Converting to correct types enables appropriate operations and often reduces memory usage. Pandas provides conversion functions (astype(), to_datetime(), to_numeric()) with options for handling errors.

Outliers: Extreme Values

Outliers are values far from the rest of the distribution. They might be errors (sensor malfunction recording impossible values) or real extreme events (billionaire customer with legitimate huge purchases). Detecting outliers involves statistical methods (values beyond 3 standard deviations) or domain knowledge (age can’t be 200). Handling them requires deciding whether to remove, cap, or transform them based on whether they’re errors or real extreme values.

Let’s work through comprehensive data cleaning:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Create deliberately messy dataset

np.random.seed(42)

n = 20

messy_data = {

'customer_id': [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10,

11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 3], # Note: ID 3 duplicated

'age': [25, 35, np.nan, 42, 31, 29, 38, np.nan, 45, 33,

28, 35, 40, np.nan, 27, 36, 200, 32, 29, np.nan], # Missing values and outlier

'income': ['50000', '75000', '60000', 'NA', '62000', '48000',

'71000', '55000', '92000', '65000',

'70000', '58000', '67000', '72000', '54000',

'69000', '61000', '66000', '73000', '60000'], # String format, NA value

'purchases': [5, 12, 7, 18, 10, 6, 15, 8, 20, 11,

9, 13, 14, 16, 7, 12, 11, 10, 14, 7],

'signup_date': ['2023-01-15', '2023-02-20', '2023-03-10', 'invalid',

'2023-04-05', '2023-05-12', '2023-06-18', '2023-07-22',

'2023-08-30', '2023-09-14', '2023-10-08', '2023-11-25',

'2023-12-03', '2024-01-17', '2024-02-09', '2024-03-15',

'2024-04-20', '2024-05-28', '2024-06-11', '2023-03-10']

}

df = pd.DataFrame(messy_data)

print("ORIGINAL MESSY DATASET")

print("=" * 60)

print(df)

print(f"\nShape: {df.shape}")

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 1: IDENTIFY ISSUES

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 1: IDENTIFYING DATA QUALITY ISSUES")

print("-" * 60)

print("\n1.1 Missing Values")

missing_summary = df.isnull().sum()

print(missing_summary[missing_summary > 0])

print("\n1.2 Data Types")

print(df.dtypes)

print("\n1.3 Duplicates")

duplicates = df.duplicated(subset=['customer_id'])

print(f"Number of duplicate customer_ids: {duplicates.sum()}")

if duplicates.sum() > 0:

print("Duplicate rows:")

print(df[duplicates])

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 2: HANDLE DUPLICATES

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 2: REMOVING DUPLICATES")

print("-" * 60)

df_clean = df.drop_duplicates(subset=['customer_id'], keep='first')

print(f"Rows before: {len(df)}")

print(f"Rows after removing duplicates: {len(df_clean)}")

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 3: FIX DATA TYPES

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 3: CORRECTING DATA TYPES")

print("-" * 60)

# Income: convert string to numeric, handle 'NA'

df_clean['income'] = pd.to_numeric(df_clean['income'], errors='coerce')

print(f"Income converted to numeric (NA became NaN)")

# Signup date: convert to datetime

df_clean['signup_date'] = pd.to_datetime(df_clean['signup_date'], errors='coerce')

print(f"Signup_date converted to datetime (invalid dates became NaT)")

print("\nUpdated data types:")

print(df_clean.dtypes)

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 4: HANDLE MISSING VALUES

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 4: HANDLING MISSING VALUES")

print("-" * 60)

print("Missing values after type conversion:")

print(df_clean.isnull().sum())

print()

# Strategy for age: fill with median (robust to outliers)

age_median = df_clean['age'].median()

print(f"Age - filling {df_clean['age'].isnull().sum()} missing values with median: {age_median}")

df_clean['age'] = df_clean['age'].fillna(age_median)

# Strategy for income: fill with mean of similar purchase levels

income_mean = df_clean['income'].mean()

print(f"Income - filling {df_clean['income'].isnull().sum()} missing values with mean: ${income_mean:.2f}")

df_clean['income'] = df_clean['income'].fillna(income_mean)

# Strategy for signup_date: drop rows (only 1-2 rows, not critical feature)

rows_before = len(df_clean)

df_clean = df_clean.dropna(subset=['signup_date'])

print(f"Signup_date - dropped {rows_before - len(df_clean)} rows with invalid dates")

print(f"\nMissing values remaining: {df_clean.isnull().sum().sum()}")

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 5: HANDLE OUTLIERS

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 5: DETECTING AND HANDLING OUTLIERS")

print("-" * 60)

# Statistical outlier detection: values beyond 3 standard deviations

age_mean = df_clean['age'].mean()

age_std = df_clean['age'].std()

age_lower = age_mean - 3 * age_std

age_upper = age_mean + 3 * age_std

print(f"Age outlier bounds: [{age_lower:.1f}, {age_upper:.1f}]")

outliers = df_clean[(df_clean['age'] < age_lower) | (df_clean['age'] > age_upper)]

print(f"Outliers detected: {len(outliers)}")

if len(outliers) > 0:

print(outliers[['customer_id', 'age']])

# Handle outliers: cap at reasonable maximum

print("\nCapping age outliers at 80 (reasonable maximum)")

df_clean['age'] = df_clean['age'].clip(upper=80)

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 6: VERIFY CLEANING

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 6: VERIFICATION AFTER CLEANING")

print("-" * 60)

print("Cleaned dataset (first 10 rows):")

print(df_clean.head(10))

print()

print("Data quality summary:")

print(f" Total rows: {len(df_clean)}")

print(f" Missing values: {df_clean.isnull().sum().sum()}")

print(f" Duplicates: {df_clean.duplicated().sum()}")

print(f" All numeric columns in valid ranges: ✓")

print("\nCleaned dataset statistics:")

print(df_clean.describe())

print()

# ==================================================================

# STEP 7: CREATE CLEAN DATASET FOR ML

# ==================================================================

print("STEP 7: PREPARING FOR MACHINE LEARNING")

print("-" * 60)

# Select relevant features

ml_features = ['age', 'income', 'purchases']

X = df_clean[ml_features]

print(f"Features ready for ML: {ml_features}")

print(f"Shape: {X.shape}")

print("\nFeature statistics:")

print(X.describe())What this code demonstrates: This example walks through a complete data cleaning workflow on a deliberately messy dataset containing common real-world issues. We start by identifying problems: missing values, wrong data types, duplicates, and outliers. We remove duplicates using drop_duplicates(). We convert data types using pd.to_numeric() and pd.to_datetime() with error handling. We handle missing values with different strategies based on the column: median for age (robust to outliers), mean for income (reasonable estimate), and dropping rows for dates (only a few affected). We detect outliers using statistical methods (3 standard deviations) and handle them by capping at reasonable values. Finally, we verify the cleaned dataset and prepare it for machine learning.

This systematic approach to data cleaning prevents problems during model training and ensures your machine learning algorithms receive high-quality input. Each step addresses specific data quality issues that would otherwise cause errors or degrade model performance.

Grouping and Aggregation: Analyzing Patterns

After cleaning data, you need to understand it. Grouping and aggregation operations answer questions like “What’s the average purchase amount per region?” or “How many customers in each age group?” These operations are fundamental to exploratory data analysis and feature engineering.

The GroupBy Operation: Split-Apply-Combine

Pandas’ groupby operation follows a split-apply-combine pattern. First, split the data into groups based on one or more columns. Second, apply a function to each group (mean, sum, count, etc.). Third, combine the results into a new structure. This pattern handles most analysis questions involving categories or groups.

Think of groupby like organizing students by class. You split all students into groups by their class. You apply an operation to each group, like calculating average grade. You combine the results to see average grades by class. This same pattern works for customers by region, transactions by month, or any categorical analysis.

Common Aggregations

Aggregation functions reduce groups to summary statistics. Common aggregations include count (how many in each group), sum (total per group), mean/median (average per group), min/max (extremes per group), and std (variation per group). Pandas lets you apply multiple aggregations simultaneously, giving complete group summaries efficiently.

Multiple Grouping Levels

Real analysis often requires grouping by multiple columns simultaneously. You might want average purchase amounts by both region AND customer tier. Pandas handles multi-level grouping naturally, producing hierarchical results that show patterns at different granularities.

Let’s explore grouping and aggregation:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Create sample sales dataset

np.random.seed(42)

n = 50

sales_data = pd.DataFrame({

'date': pd.date_range('2024-01-01', periods=n, freq='D'),

'product': np.random.choice(['Laptop', 'Phone', 'Tablet'], n),

'region': np.random.choice(['North', 'South', 'East', 'West'], n),

'customer_type': np.random.choice(['New', 'Returning'], n),

'quantity': np.random.randint(1, 10, n),

'unit_price': np.random.choice([500, 800, 300], n),

})

sales_data['revenue'] = sales_data['quantity'] * sales_data['unit_price']

sales_data['month'] = sales_data['date'].dt.to_period('M')

print("SALES DATASET")

print("=" * 60)

print(sales_data.head(10))

print(f"\nTotal records: {len(sales_data)}")

print()

# ==================================================================

# BASIC GROUPING

# ==================================================================

print("1. BASIC GROUPING OPERATIONS")

print("-" * 60)

# Group by single column, single aggregation

print("\nAverage revenue by product:")

revenue_by_product = sales_data.groupby('product')['revenue'].mean()

print(revenue_by_product)

print()

# Group by single column, multiple aggregations

print("Revenue statistics by region:")

region_stats = sales_data.groupby('region')['revenue'].agg(['count', 'sum', 'mean', 'std'])

print(region_stats)

print()

# Group by multiple columns

print("Average revenue by product and region:")

product_region = sales_data.groupby(['product', 'region'])['revenue'].mean()

print(product_region)

print()

# ==================================================================

# ADVANCED AGGREGATIONS

# ==================================================================

print("\n2. ADVANCED AGGREGATION PATTERNS")

print("-" * 60)

# Multiple columns, multiple aggregations

print("Comprehensive sales analysis by product:")

product_analysis = sales_data.groupby('product').agg({

'revenue': ['sum', 'mean', 'count'],

'quantity': ['sum', 'mean'],

'unit_price': 'mean'

})

print(product_analysis)

print()

# Custom aggregation function

def revenue_range(x):

return x.max() - x.min()

print("Revenue range (max - min) by region:")

revenue_range_by_region = sales_data.groupby('region')['revenue'].agg(revenue_range)

print(revenue_range_by_region)

print()

# ==================================================================

# FILTERING GROUPS

# ==================================================================

print("\n3. FILTERING GROUPS")

print("-" * 60)

# Keep only groups with more than 5 sales

print("Regions with more than 5 sales:")

region_counts = sales_data.groupby('region').size()

high_volume_regions = region_counts[region_counts > 5]

print(high_volume_regions)

print()

# Filter original data to high-volume regions

df_high_volume = sales_data[sales_data['region'].isin(high_volume_regions.index)]

print(f"Sales from high-volume regions: {len(df_high_volume)} records")

print()

# ==================================================================

# TIME-BASED GROUPING

# ==================================================================

print("\n4. TIME-BASED ANALYSIS")

print("-" * 60)

print("Monthly revenue trend:")

monthly_revenue = sales_data.groupby('month')['revenue'].sum()

print(monthly_revenue)

print()

print("Sales count by product and month:")

product_monthly = sales_data.groupby(['product', 'month']).size().unstack(fill_value=0)

print(product_monthly)

print()

# ==================================================================

# TRANSFORM AND APPLY

# ==================================================================

print("\n5. TRANSFORM: ADD GROUP STATISTICS TO ORIGINAL DATA")

print("-" * 60)

# Add average revenue by product to each row

sales_data['product_avg_revenue'] = sales_data.groupby('product')['revenue'].transform('mean')

# Add rank within each product group

sales_data['revenue_rank_in_product'] = sales_data.groupby('product')['revenue'].rank(ascending=False)

print("Original data with added group statistics (first 10 rows):")

print(sales_data[['product', 'revenue', 'product_avg_revenue', 'revenue_rank_in_product']].head(10))

print()

# ==================================================================

# PRACTICAL ML EXAMPLE: FEATURE ENGINEERING

# ==================================================================

print("\n6. FEATURE ENGINEERING WITH GROUPBY")

print("-" * 60)

# Create features based on group statistics

feature_engineering = sales_data.copy()

# Revenue relative to product average (above/below average)

feature_engineering['revenue_vs_product_avg'] = (

feature_engineering['revenue'] - feature_engineering['product_avg_revenue']

)

# Customer type distribution by region (for categorical encoding)

region_customer_dist = sales_data.groupby(['region', 'customer_type']).size().unstack(fill_value=0)

region_customer_dist['returning_ratio'] = (

region_customer_dist['Returning'] / (region_customer_dist['New'] + region_customer_dist['Returning'])

)

print("Customer type distribution by region:")

print(region_customer_dist)

print()

# Day of week pattern

sales_data['day_of_week'] = sales_data['date'].dt.dayofweek

dow_revenue = sales_data.groupby('day_of_week')['revenue'].mean()

print("Average revenue by day of week (0=Monday):")

print(dow_revenue)

print()

# ==================================================================

# SUMMARY INSIGHTS

# ==================================================================

print("\n7. KEY INSIGHTS FROM GROUPING")

print("-" * 60)

# Top performing product

top_product = sales_data.groupby('product')['revenue'].sum().idxmax()

top_revenue = sales_data.groupby('product')['revenue'].sum().max()

# Most valuable region

top_region = sales_data.groupby('region')['revenue'].sum().idxmax()

region_revenue = sales_data.groupby('region')['revenue'].sum().max()

# Best customer type

customer_value = sales_data.groupby('customer_type')['revenue'].mean()

print(f"Top product: {top_product} (${top_revenue:,.2f} total revenue)")

print(f"Top region: {top_region} (${region_revenue:,.2f} total revenue)")

print(f"\nCustomer value analysis:")

print(customer_value)What this code demonstrates: This comprehensive example shows the full power of grouping and aggregation. We start with basic groupby operations on single columns with single aggregations. We progress to multiple columns and multiple aggregations simultaneously. We apply custom aggregation functions. We filter groups based on size or characteristics. We perform time-based grouping to analyze trends. We use transform() to add group statistics back to the original DataFrame. We demonstrate practical feature engineering using groupby: creating relative metrics, distribution ratios, and time-based patterns. Finally, we extract business insights by identifying top performers across different dimensions.

Grouping and aggregation are essential skills because they transform raw transactional data into meaningful insights. Whether analyzing customer segments, identifying trends, or engineering features for machine learning, you’ll use groupby operations constantly.

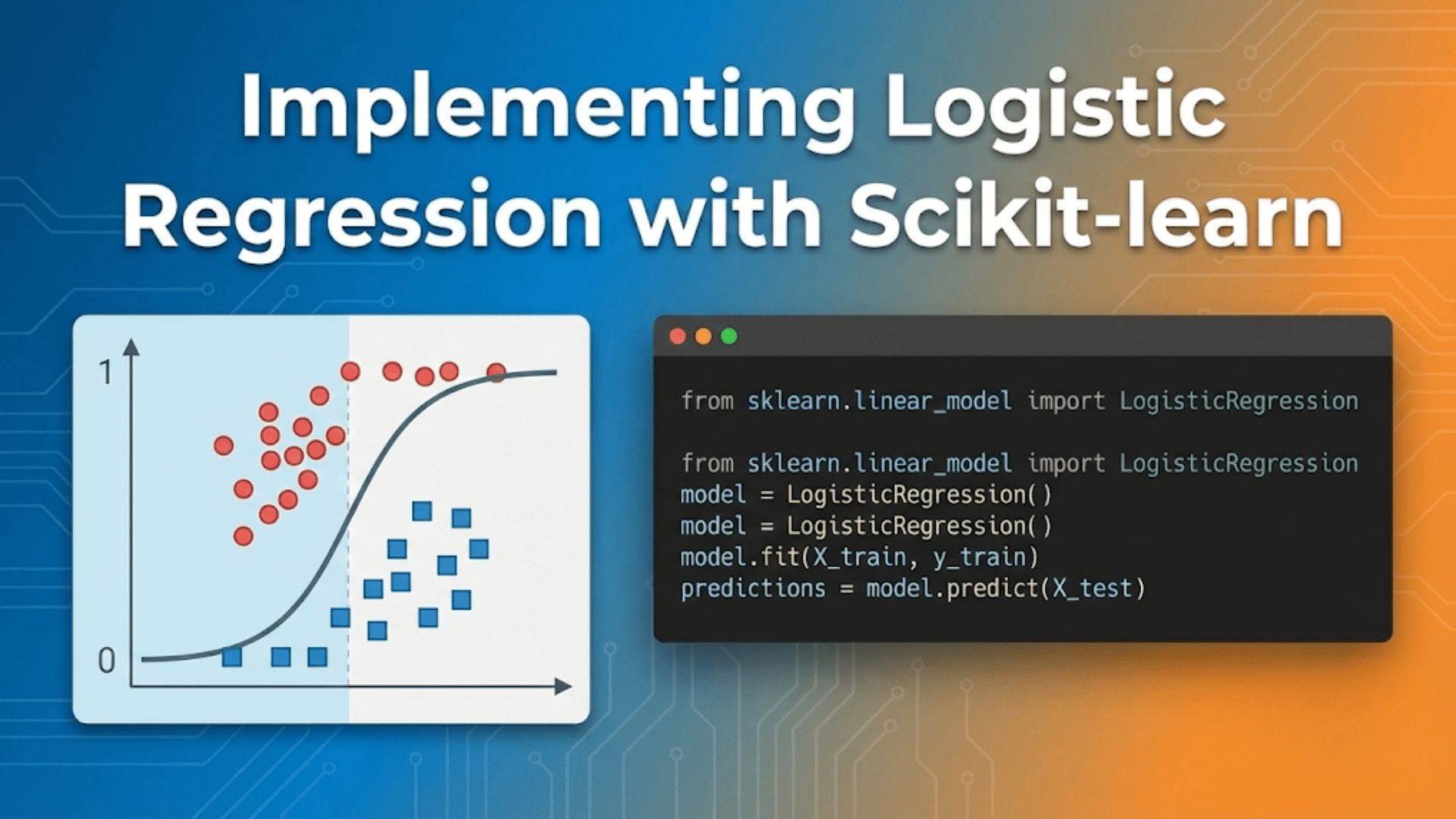

Conclusion: From Raw Data to Machine Learning Ready

Mastering Pandas transforms you from someone who can load data into someone who can systematically prepare it for machine learning. The skills covered in this guide—understanding DataFrames and Series, loading data efficiently, selecting and filtering precisely, cleaning methodically, and analyzing through grouping—form the foundation of data preparation for AI projects.

Every machine learning project follows a similar pattern. You load raw data into DataFrames. You inspect it to understand structure, identify issues, and plan your approach. You clean it by handling missing values, removing duplicates, correcting types, and addressing outliers. You explore it through grouping and aggregation to understand patterns and relationships. You engineer features by creating new columns from existing ones, often using group statistics. You select and filter to create final datasets for model training.

Pandas makes each step efficient through its intuitive API and powerful operations. What would require hundreds of lines of custom code becomes single method calls or simple method chains. This efficiency lets you spend time thinking about your data and model rather than fighting with syntax.

The key to Pandas mastery is practice with real datasets. Load data from your domain and work through the complete preparation process. Encounter actual data quality issues and solve them. Discover patterns through grouping. Create features that improve model performance. Each dataset teaches you something new and reinforces fundamental patterns.

Remember that data preparation isn’t a chore to rush through—it’s where you build deep understanding of your problem. The insights you gain while cleaning, exploring, and engineering features often matter more than the specific model you choose later. A carefully prepared dataset with well-engineered features will outperform a sophisticated model trained on raw, messy data.

As you continue your machine learning journey, Pandas will be your constant companion. Whether loading data, exploring distributions, engineering features, or preparing final training sets, you’ll use Pandas daily. The investment you make in mastering it pays dividends throughout your career in AI and data science.