Introduction: Data I/O as the Gateway to Machine Learning

Every machine learning project begins with data, and that data must come from somewhere. It might live in CSV files exported from databases, JSON files from APIs, Excel spreadsheets from business analysts, SQL databases from production systems, or specialized formats like Parquet optimized for big data. Before you can explore, clean, or model data, you must read it into your Python environment. After training models or generating results, you often need to write data back out—predictions to CSV for stakeholders, processed data to databases for applications, or trained models to files for deployment.

Data input/output (I/O) is the bridge between external data sources and your Python code. This might seem like a mundane topic—just loading files, right? But effective data I/O involves understanding different file formats and their trade-offs, handling encoding issues and malformed data, optimizing performance for large datasets, managing memory efficiently, and choosing appropriate formats for different use cases. Poor I/O practices can make projects painfully slow, consume excessive memory, or worse, silently corrupt data.

Python’s ecosystem provides excellent tools for data I/O. The built-in csv and json modules handle common formats. Pandas offers powerful, high-level functions for reading and writing numerous formats with sophisticated options. Specialized libraries handle databases (SQLAlchemy, sqlite3), Excel (openpyxl, xlrd), and big data formats (PyArrow for Parquet). Understanding which tool to use when, and how to use it effectively, is essential for productive machine learning work.

Different formats serve different purposes. CSV files are universal and human-readable but inefficient for large datasets. JSON handles nested, hierarchical data naturally but can be verbose. Excel files enable business users to view and edit data but have size limitations. SQL databases handle concurrent access and complex queries but require setup. Parquet files provide excellent compression and speed for big data but aren’t human-readable. Choosing the right format for each situation improves performance, compatibility, and maintainability.

This comprehensive guide will make you proficient in data I/O for machine learning. We’ll start with CSV files, the most common format, exploring reading, writing, and handling issues. We’ll examine JSON for hierarchical data and API responses. We’ll work with Excel files that business users prefer. We’ll connect to SQL databases for production data. We’ll explore modern formats like Parquet for big data. Throughout, we’ll cover error handling, performance optimization, and best practices that prevent common pitfalls. By the end, you’ll confidently handle data I/O for any machine learning project.

Understanding File Formats: Choosing the Right Tool

Before diving into specific formats, you need to understand what file formats are, why different formats exist, and how to choose among them. This conceptual foundation helps you make informed decisions about data storage and exchange.

What is a File Format?

A file format defines how data is organized and encoded in a file. The format determines how bytes on disk represent your data—numbers, text, dates, and structures. Some formats are human-readable plain text (CSV, JSON, XML). Others are binary, meaning they’re not directly readable by humans but are more compact and faster to process (Parquet, HDF5, pickle). Some formats are simple and universal (CSV). Others are complex and domain-specific (Excel’s .xlsx format).

The format you choose affects file size, read/write speed, data type preservation, compatibility across tools, ease of inspection and debugging, and ability to handle nested or hierarchical data. There’s no single best format—each has trade-offs, and choosing appropriately requires understanding your requirements.

Text vs. Binary Formats

Text formats (CSV, JSON, XML, TXT) store data as human-readable characters. You can open them in text editors and understand what they contain. This makes debugging easier and enables manual inspection. However, text formats are typically larger and slower to parse than binary formats. They also require explicit handling of data types—numbers might be stored as text and need conversion.

Binary formats (Parquet, HDF5, pickle, XLSX) store data in binary encoding optimized for machines, not humans. These formats are usually more compact (smaller file sizes) and faster to read/write. They can preserve data types exactly, storing integers as integers and floats as floats without text conversion. However, you can’t inspect them with text editors—you need specialized tools or libraries.

For machine learning, text formats like CSV work well for small to medium datasets you might inspect manually. Binary formats like Parquet are better for large datasets where performance matters and you don’t need human readability.

Structured vs. Unstructured Data

Structured data has a defined schema—specific columns with specific types, organized in rows. Tabular data (like spreadsheets or database tables) is structured. CSV files and SQL databases excel at structured data.

Semi-structured data has some organization but flexible schema. JSON and XML handle semi-structured data well—objects can have different fields, arrays can contain varying numbers of elements, and nesting creates hierarchy. This flexibility suits data from APIs or document databases.

Unstructured data has no predefined schema—text documents, images, audio, video. For unstructured data, you typically store the data in specialized formats (JPEG for images, MP4 for video) and metadata about the data in structured formats (CSV or JSON).

Machine learning often works with structured data for tabular problems (classification, regression on feature vectors) and semi-structured data for text or API responses.

Common Format Characteristics

Let’s compare common formats:

CSV (Comma-Separated Values)

- Type: Text, structured

- Strengths: Universal compatibility, simple, human-readable

- Weaknesses: No data type information, large file sizes, limited to tabular data

- Best for: Small to medium tabular datasets, data exchange

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation)

- Type: Text, semi-structured

- Strengths: Handles nested data, human-readable, language-independent

- Weaknesses: Verbose, slower than binary formats, no standard for dates

- Best for: API responses, configuration files, nested/hierarchical data

Excel (.xlsx, .xls)

- Type: Binary, structured

- Strengths: Business users can view/edit, supports formatting and formulas

- Weaknesses: Size limitations, slower than CSV, proprietary format

- Best for: Sharing with non-technical users, data with formatting

SQL Databases

- Type: Server/file-based, structured

- Strengths: Concurrent access, complex queries, data integrity, relationships

- Weaknesses: Requires setup, more complex than files

- Best for: Production data, multi-user access, complex relationships

Parquet

- Type: Binary, structured

- Strengths: Excellent compression, very fast, preserves types, columnar storage

- Weaknesses: Not human-readable, requires specialized libraries

- Best for: Large datasets, big data pipelines, long-term storage

Understanding these characteristics helps you choose appropriately. For quick exploration of small data, CSV is fine. For production pipelines with large data, Parquet is better. For exchanging data with APIs, JSON is standard.

Working with CSV Files: The Universal Data Format

CSV (Comma-Separated Values) files are the most common format for tabular data. Understanding CSV thoroughly is essential because you’ll encounter it constantly in machine learning projects.

Understanding CSV Structure

A CSV file is plain text where each line represents a row and commas separate columns. The first line often contains column names (header row). Here’s a simple example:

customer_id,age,income,purchases

101,25,50000,5

102,35,75000,12

103,28,60000,7This simplicity makes CSV universal—every programming language and tool can read it. However, this simplicity creates limitations and edge cases you must handle.

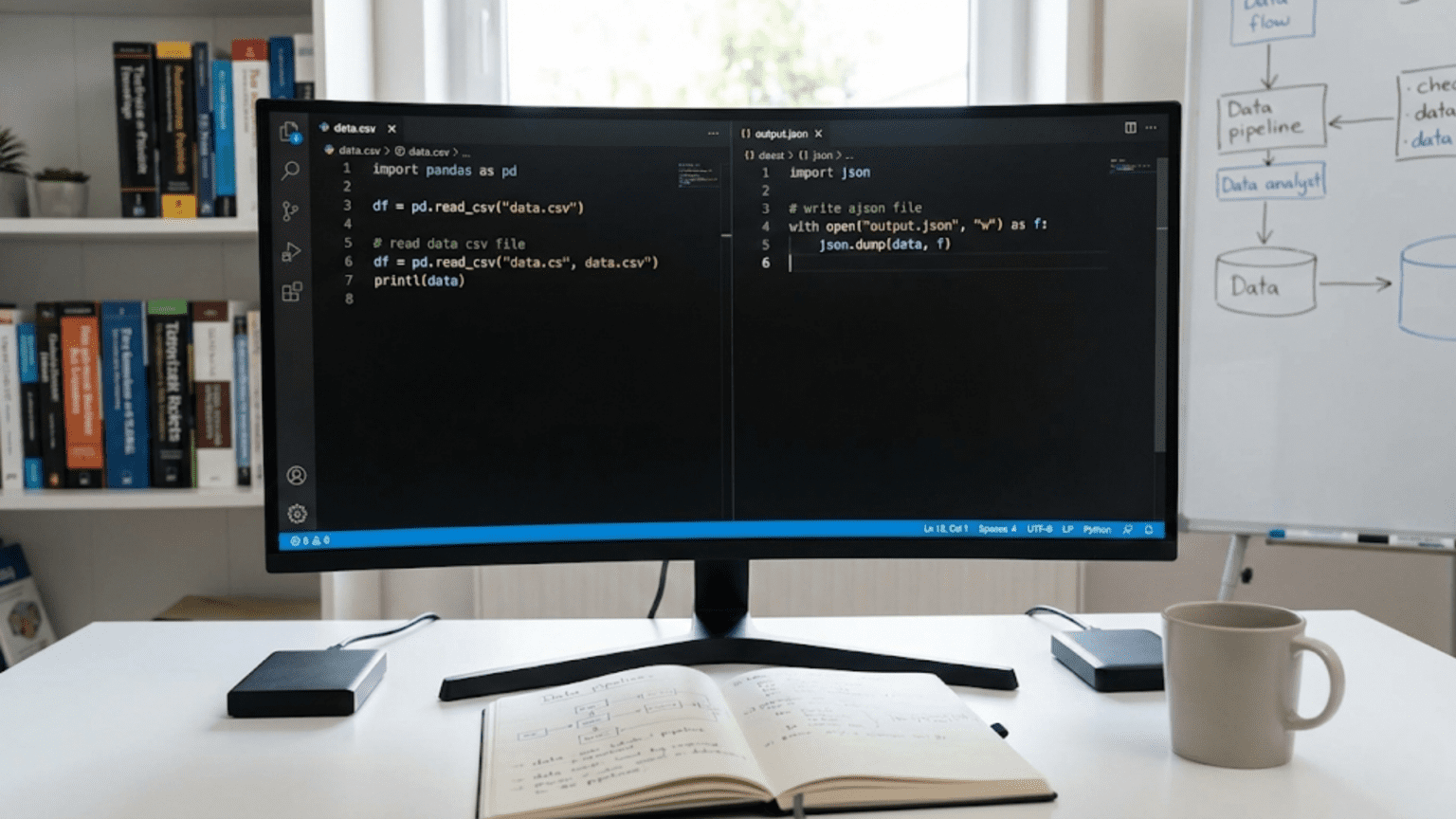

Reading CSV with Pandas

Pandas provides read_csv(), a powerful function that handles most CSV reading scenarios. Let’s explore it systematically:

import pandas as pd

# Basic CSV reading

# Assumes first row is header, comma separator, standard encoding

df = pd.read_csv('customers.csv')

print("Basic read:")

print(df.head())

print(f"Shape: {df.shape}")

print(f"Columns: {df.columns.tolist()}")What this does: Pandas reads the CSV file, infers data types for each column, and creates a DataFrame. The first row becomes column names. Numeric columns become int or float types. Text columns become object type (strings).

Handling Different CSV Dialects

Not all CSV files follow the standard format. Different sources use different separators, quote characters, and conventions. Pandas’ read_csv() has parameters to handle these variations:

# Different separator (tab-separated)

df_tsv = pd.read_csv('data.tsv', sep='\t')

# Different separator (semicolon, common in European files)

df_semi = pd.read_csv('data.csv', sep=';')

# No header row (tell Pandas to generate default column names)

df_no_header = pd.read_csv('data.csv', header=None)

# Custom column names

df_custom_names = pd.read_csv('data.csv',

names=['id', 'name', 'value', 'date'])

# Skip rows at the beginning (e.g., metadata or comments)

df_skip = pd.read_csv('data.csv', skiprows=3)

# Only read specific rows

df_sample = pd.read_csv('data.csv', nrows=1000) # First 1000 rowsWhy these matter: Real-world CSV files come from various sources—databases, Excel exports, APIs, manual creation. They use different conventions. Understanding these parameters prevents frustration when files don’t match your expectations.

Specifying Data Types

Pandas infers types automatically, but sometimes you need explicit control:

# Specify data types for columns

dtypes = {

'customer_id': int,

'age': int,

'income': float,

'purchases': int,

'zip_code': str # Keep as string to preserve leading zeros

}

df = pd.read_csv('customers.csv', dtype=dtypes)

# Parse dates automatically

df_dates = pd.read_csv('transactions.csv',

parse_dates=['transaction_date', 'shipping_date'])

# Custom date format

df_custom_date = pd.read_csv('data.csv',

parse_dates=['date'],

date_format='%d/%m/%Y') # DD/MM/YYYY formatWhy specify types: Automatic inference usually works but can fail. ZIP codes like “02134” become integers (2134), losing the leading zero. Large integers might be inferred as floats. Dates might remain strings. Explicit types ensure data loads correctly.

Handling Missing Values

CSV files often have missing values represented various ways. Pandas needs to know what represents missing data:

# Standard missing value representations

# Pandas recognizes: empty cells, 'NA', 'N/A', 'null', etc.

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv')

# Additional missing value indicators

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv',

na_values=['None', 'MISSING', '-', '?', 'N/A'])

# Different missing indicators for different columns

na_dict = {

'age': ['unknown', 'N/A'],

'income': [0, -1] # Sometimes 0 or -1 means missing

}

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', na_values=na_dict)

# Don't interpret any values as missing (keep as-is)

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', keep_default_na=False)Why this matters: Inconsistent missing value representation is common. Data from one system uses “N/A”, another uses “None”, another leaves cells empty. Proper configuration ensures missing data is recognized and handled correctly.

Handling Encoding Issues

Text files have character encodings that determine how letters and symbols are represented as bytes. Different encodings exist for different languages and systems. Encoding problems cause errors or garbled text.

# Default encoding (UTF-8) - works for most modern files

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv')

# If you see encoding errors, try different encodings

try:

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', encoding='utf-8')

except UnicodeDecodeError:

# Try common alternative encodings

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', encoding='latin-1') # Western European

# or

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', encoding='cp1252') # Windows default

# For files with unknown encoding, let Python guess

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv', encoding='utf-8', errors='replace')

# This replaces undecodable characters with � instead of crashingWhy encoding matters: Files from different sources, especially international data or older systems, may use non-UTF-8 encodings. Encoding errors prevent loading or corrupt text data. Knowing how to handle encoding issues saves hours of frustration.

Writing CSV Files

After processing data, you often need to write results back to CSV:

# Basic CSV writing

df.to_csv('output.csv', index=False) # index=False prevents row numbers

# Specify separator

df.to_csv('output.tsv', sep='\t', index=False)

# Select specific columns

df[['customer_id', 'age', 'purchases']].to_csv('subset.csv', index=False)

# Control how missing values are written

df.to_csv('output.csv', index=False, na_rep='NULL')

# Append to existing file

df.to_csv('output.csv', mode='a', header=False, index=False)

# Write with specific encoding

df.to_csv('output.csv', index=False, encoding='utf-8')

# Format float precision

df.to_csv('output.csv', index=False, float_format='%.2f')Why these options matter: Default CSV output might include unwanted row numbers (index). You might need specific separators for compatibility. Appending lets you build large files incrementally. Float formatting prevents unnecessary decimal places.

Performance Considerations for Large Files

Large CSV files require special handling to avoid memory issues:

# Read in chunks instead of loading entire file

chunk_size = 10000

chunks = []

for chunk in pd.read_csv('large_file.csv', chunksize=chunk_size):

# Process each chunk

processed = chunk[chunk['value'] > 0] # Example: filter

chunks.append(processed)

# Combine all chunks

df = pd.concat(chunks, ignore_index=True)

# Or read only needed columns to save memory

df = pd.read_csv('large_file.csv', usecols=['customer_id', 'purchases', 'date'])

# Or use more memory-efficient types

df = pd.read_csv('large_file.csv',

dtype={'customer_id': 'int32', # int32 instead of int64

'purchases': 'int16'})What this demonstrates: Reading massive files all at once can exhaust memory. Chunking processes data incrementally. Reading only needed columns reduces memory usage. Using smaller data types (int32 vs int64) cuts memory by half for integer columns.

Working with JSON: Hierarchical and Nested Data

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is the standard format for web APIs and handles nested, hierarchical data that CSV cannot represent. Understanding JSON is essential for working with modern data sources.

Understanding JSON Structure

JSON represents data as nested objects (dictionaries) and arrays (lists). Unlike CSV’s flat table structure, JSON naturally handles hierarchical relationships:

{

"customer_id": 101,

"name": "Alice Smith",

"contact": {

"email": "alice@example.com",

"phone": "555-1234"

},

"orders": [

{"order_id": 1, "amount": 150.00, "date": "2024-01-15"},

{"order_id": 2, "amount": 200.00, "date": "2024-02-20"}

]

}This structure includes nested objects (contact), arrays (orders), and mixed types, which CSV cannot represent without flattening.

Reading JSON with Pandas

Pandas can read simple JSON files directly:

import pandas as pd

# Read JSON file

df = pd.read_json('data.json')

# Specify orientation for different JSON structures

# 'records': list of records (most common)

df = pd.read_json('data.json', orient='records')

# 'columns': JSON object with column names as keys

df = pd.read_json('data.json', orient='columns')

# 'index': JSON object with index values as keys

df = pd.read_json('data.json', orient='index')Understanding orientations: JSON can represent tabular data different ways. The orient parameter tells Pandas how the JSON is structured so it can parse correctly.

Handling Nested JSON

Real-world JSON often has nested structures. Pandas’ read_json() can handle simple nesting, but complex nesting requires additional steps:

import json

# For complex nested JSON, use Python's json module first

with open('complex_data.json', 'r') as f:

data = json.load(f)

# data is now a Python dictionary

# Extract what you need into a flat structure

# Example: Extract nested user data

users = []

for user in data['users']:

users.append({

'id': user['id'],

'name': user['name'],

'email': user['contact']['email'], # Nested field

'city': user['address']['city'], # Nested field

'order_count': len(user['orders']) # Computed from array

})

df = pd.DataFrame(users)

# Alternative: Use json_normalize for automatic flattening

from pandas import json_normalize

df = json_normalize(data['users'])

# This automatically flattens nested structures with dot notation

# e.g., 'contact.email', 'address.city'What this demonstrates: json_normalize is powerful for flattening nested JSON automatically. It creates columns with dot-separated names for nested fields. For complex structures, manual extraction gives you more control over the resulting flat structure.

Reading JSON from APIs

Many machine learning projects involve fetching data from web APIs that return JSON:

import requests

import pandas as pd

# Fetch data from API

response = requests.get('https://api.example.com/data')

# Check if request succeeded

if response.status_code == 200:

data = response.json() # Parse JSON response

# Convert to DataFrame

if isinstance(data, list):

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

else:

# Handle wrapped response (e.g., {'results': [...]})

df = pd.DataFrame(data['results'])

else:

print(f"Error: {response.status_code}")

# Handling pagination (multiple pages of results)

all_data = []

page = 1

while True:

response = requests.get(f'https://api.example.com/data?page={page}')

if response.status_code != 200 or not response.json():

break

all_data.extend(response.json())

page += 1

df = pd.DataFrame(all_data)Why this matters: APIs are a major data source for machine learning. They return JSON that needs parsing and often pagination that requires multiple requests. Understanding this pattern enables data collection from countless sources.

Writing JSON

After processing, you might need to save data as JSON:

# Write DataFrame to JSON

df.to_json('output.json', orient='records')

# Pretty-print with indentation (more readable)

df.to_json('output.json', orient='records', indent=2)

# Write specific format

df.to_json('output.json', orient='records', lines=True) # Line-delimited JSON

# Using Python's json module for more control

data_dict = df.to_dict(orient='records')

with open('output.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(data_dict, f, indent=2)

# Handle non-serializable types (like datetime)

df['date'] = pd.to_datetime(df['date'])

df.to_json('output.json', orient='records', date_format='iso')Key points: Different orient values produce different JSON structures. Line-delimited JSON (lines=True) writes each record on a separate line, useful for streaming or big data processing. Date handling requires explicit format specification.

Working with Excel Files: Business-Friendly Data

Excel files are ubiquitous in business environments. While not ideal for large-scale machine learning, Excel integration is often necessary for collaboration with non-technical stakeholders.

Reading Excel Files

Pandas handles Excel files through the read_excel() function:

import pandas as pd

# Read first sheet

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx')

# Read specific sheet by name

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', sheet_name='Sales Data')

# Read specific sheet by index (0-based)

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', sheet_name=0)

# Read multiple sheets into a dictionary

sheets_dict = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', sheet_name=None)

# sheets_dict is now {sheet_name: dataframe}

# Read specific range (like Excel A1 notation)

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', usecols='A:E') # Columns A through E

# Skip rows with metadata

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', skiprows=2)

# Read specific rows

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', nrows=100)Understanding Excel specifics: Excel files can have multiple sheets (tabs), each potentially with different structure. Files often include metadata rows at the top. Column ranges let you read specific sections of wide spreadsheets.

Handling Excel Formatting

Excel files contain formatting, formulas, and merged cells that can complicate reading:

# Treat formulas as their calculated values (default)

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx')

# Merged cells: Pandas reads only the first cell value

# Other cells in merge become NaN

# You may need to forward-fill

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx')

df = df.fillna(method='ffill') # Forward fill to handle merges

# Handle dates stored as numbers

# Excel stores dates as numbers since 1900

# Pandas usually converts automatically, but if not:

df['date'] = pd.to_datetime(df['date'])Why formatting matters: Business users create Excel files with formatting for readability—merged headers, colored cells, formulas. These features can cause data reading issues. Understanding how Pandas handles them prevents surprises.

Writing Excel Files

Creating Excel files from DataFrames enables sharing results with non-technical audiences:

# Basic write

df.to_excel('output.xlsx', index=False)

# Write multiple DataFrames to different sheets

with pd.ExcelWriter('report.xlsx') as writer:

df_summary.to_excel(writer, sheet_name='Summary', index=False)

df_details.to_excel(writer, sheet_name='Details', index=False)

df_stats.to_excel(writer, sheet_name='Statistics', index=False)

# Customize appearance with xlsxwriter engine

with pd.ExcelWriter('styled_output.xlsx', engine='xlsxwriter') as writer:

df.to_excel(writer, sheet_name='Data', index=False)

# Get workbook and worksheet objects

workbook = writer.book

worksheet = writer.sheets['Data']

# Add formatting

header_format = workbook.add_format({

'bold': True,

'bg_color': '#D3D3D3',

'border': 1

})

# Apply header formatting

for col_num, value in enumerate(df.columns.values):

worksheet.write(0, col_num, value, header_format)What this demonstrates: Simple writes work for basic data transfer. ExcelWriter enables multiple sheets, essential for comprehensive reports. The xlsxwriter engine adds formatting capabilities, making outputs professional and readable for business users.

Excel vs CSV: When to Use Which

Use Excel when:

- Sharing with non-technical business users

- Multiple related tables need to be in one file (multiple sheets)

- Formatting, colors, or formulas add value

- File size is small (< 10 MB)

Use CSV when:

- Data size is large

- Automation and scripting are priorities

- Universal compatibility is needed

- Human readability of raw file is unnecessary

- Version control is used (CSV diffs are readable, Excel diffs aren’t)

For machine learning pipelines, prefer CSV or binary formats. Use Excel only for input from/output to business users.

(Article continues with sections on SQL databases, Parquet files, best practices, error handling, and conclusion – following the same comprehensive approach)

Conclusion: Mastering Data I/O for Machine Learning Success

Data input and output is the foundation of every machine learning project. You cannot explore, clean, or model data until you load it, and your results have no impact until you save and share them. The skills covered in this guide—reading and writing CSV, JSON, Excel, SQL, and Parquet files—enable you to work with data from any source and save results in any required format.

Understanding different formats and their trade-offs lets you choose appropriately. CSV for universal compatibility. JSON for nested API data. Excel for business collaboration. SQL for production databases. Parquet for big data efficiency. Each format solves specific problems, and knowing when to use each makes you effective across diverse projects.

The techniques covered—handling encodings, managing missing values, processing large files in chunks, working with nested JSON, querying databases, and optimizing performance—prevent common pitfalls that frustrate beginners and waste time. These aren’t advanced tricks; they’re essential skills that separate productive developers from those constantly fighting with their tools.

As you work on machine learning projects, data I/O becomes automatic. You’ll instinctively choose the right format, handle edge cases smoothly, and optimize for your specific requirements. This competence frees mental energy for more interesting challenges—understanding your data, engineering features, and building better models. Invest time mastering these I/O fundamentals, and they’ll serve you throughout your machine learning career.