Introduction: Why Python Dominates Machine Learning

Python has become the undisputed leader in machine learning and artificial intelligence development. This dominance is not accidental—Python combines several characteristics that make it uniquely suited for AI work. The language emphasizes code readability through its clean, English-like syntax, allowing developers to focus on solving problems rather than wrestling with complex language constructs. Python’s extensive ecosystem includes powerful libraries specifically designed for scientific computing, data analysis, and machine learning, from NumPy and Pandas for data manipulation to TensorFlow and PyTorch for deep learning.

The interpreted nature of Python enables rapid experimentation, a crucial feature when developing and testing machine learning models. You can write a few lines of code, execute them immediately, see the results, and iterate—this interactive workflow accelerates the learning process and makes debugging much easier. Additionally, Python’s dynamic typing means you don’t need to declare variable types explicitly, reducing boilerplate code and making scripts more concise. The language supports multiple programming paradigms including procedural, object-oriented, and functional programming, giving you flexibility in how you structure your code.

For aspiring AI developers, learning Python is not just about understanding syntax—it’s about developing a computational mindset. You need to think about how to break complex problems into smaller, manageable pieces. You need to understand how data flows through your program. You need to recognize patterns and abstract them into reusable functions and classes. This article will build these fundamental skills systematically, starting from the very basics and progressing to concepts you’ll use daily in machine learning projects.

We will cover the essential building blocks of Python programming: variables and data types that store information, operators that manipulate data, control structures that direct program flow, functions that organize reusable code, and object-oriented programming that models real-world entities. Throughout, we’ll connect these concepts to their applications in machine learning, helping you understand not just what each feature does, but why it matters for AI development.

Understanding Variables and Data Types

Variables are fundamental to programming—they are named containers that store data in your computer’s memory. When you create a variable, you’re essentially reserving a space in memory and giving it a name so you can refer to that data later. Unlike many programming languages where you must explicitly declare what type of data a variable will hold, Python uses dynamic typing, which means the interpreter automatically determines the data type based on the value you assign.

Think of variables as labeled boxes in a warehouse. Each box (variable) has a label (name) and contains something (value). You can change what’s inside the box, you can move contents between boxes, and you can create new boxes as needed. The key difference from physical boxes is that in programming, when you “assign” the contents of one variable to another, you’re typically copying the value rather than moving it.

The Core Data Types in Python

Python provides several built-in data types, each designed for different purposes. Understanding when to use each type is crucial for writing efficient, correct code.

Integers represent whole numbers without decimal points. You use integers for counting, indexing into lists, and any situation where fractional values don’t make sense. In machine learning, you commonly use integers for iteration counters, array indices, and categorical labels. For example, if you’re classifying images into ten categories, you might represent each category with an integer from 0 to 9.

Floating-point numbers (floats) represent numbers with decimal points. These are essential for scientific computing because most real-world measurements involve fractional values. Machine learning weights, feature values, and loss values are typically floats. However, be aware that floating-point arithmetic has limitations due to how computers represent decimal numbers—very small rounding errors can accumulate, which matters in some numerical algorithms.

Strings are sequences of characters used for text data. In AI applications, strings appear constantly: file paths, column names in datasets, text data for natural language processing, and model architecture specifications. Strings are immutable in Python, meaning once created, their content cannot be changed—any operation that appears to modify a string actually creates a new string.

Booleans represent truth values: True or False. These are fundamental for logic and control flow. In machine learning, booleans are used for masking data (selecting specific rows or columns), representing binary features, and controlling algorithm behavior. Boolean operations underlie decision trees, logic-based rules, and conditional data processing.

Let me show you how these types work in practice:

# Integer variables - whole numbers

num_samples = 1000 # Number of training examples

num_features = 10 # Number of input features

batch_size = 32 # Samples per training batch

print(f"Training {num_samples} samples with {num_features} features")

print(f"Batch size: {batch_size}")

print(f"Type of num_samples: {type(num_samples)}")

print()

# Float variables - decimal numbers

learning_rate = 0.001 # Step size for gradient descent

dropout_rate = 0.5 # Fraction of neurons to drop

accuracy = 0.9234 # Model accuracy

print(f"Learning rate: {learning_rate}")

print(f"Dropout rate: {dropout_rate}")

print(f"Accuracy: {accuracy:.2%}") # Format as percentage

print(f"Type of learning_rate: {type(learning_rate)}")

print()

# String variables - text data

model_name = "ResNet50"

dataset_path = "/data/imagenet/train"

optimizer = "Adam"

print(f"Model: {model_name}")

print(f"Dataset location: {dataset_path}")

print(f"Optimizer: {optimizer}")

print(f"Type of model_name: {type(model_name)}")

print()

# Boolean variables - True/False

is_training = True

use_gpu = True

model_loaded = False

print(f"Is training mode: {is_training}")

print(f"Using GPU: {use_gpu}")

print(f"Model loaded: {model_loaded}")

print(f"Type of is_training: {type(is_training)}")This example demonstrates several important concepts. First, notice how we don’t need to declare types—Python infers them from the values. Second, the f-string formatting (strings with f"") provides a clean way to embed variables in text. Third, the type() function lets you check what type a variable actually is, which is useful for debugging.

Type Conversion and Coercion

Sometimes you need to convert between types. This is called type casting or type conversion. Understanding when and how to convert types prevents bugs and enables you to work with data from different sources that might represent the same information differently.

# Explicit type conversion

num_string = "42"

num_int = int(num_string) # Convert string to integer

num_float = float(num_string) # Convert string to float

print(f"Original string: '{num_string}' (type: {type(num_string)})")

print(f"Converted to int: {num_int} (type: {type(num_int)})")

print(f"Converted to float: {num_float} (type: {type(num_float)})")

print()

# Converting numbers to strings

epochs = 100

message = "Training for " + str(epochs) + " epochs"

print(message)

print()

# Boolean conversions - important for data filtering

# In Python, 0, 0.0, empty strings, and None are "falsy"

# Everything else is "truthy"

print(f"bool(1): {bool(1)}") # True

print(f"bool(0): {bool(0)}") # False

print(f"bool(''): {bool('')}") # False (empty string)

print(f"bool('text'): {bool('text')}") # True

print(f"bool([]): {bool([])}") # False (empty list)The concept of “truthy” and “falsy” values is particularly important in machine learning when filtering data or applying conditional logic. Any non-zero number is truthy, empty collections are falsy, and this behavior lets you write concise conditional expressions.

Operators: Performing Operations on Data

Operators are symbols that tell Python to perform specific operations on values. They’re the verbs of programming—they do things. Understanding operators is essential because they appear in every calculation, comparison, and logical decision in your code.

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators perform mathematical calculations. These are the foundation of all numerical computing in machine learning.

The addition operator + combines numbers and also concatenates strings. The subtraction operator - finds differences. The multiplication operator * multiplies numbers and can repeat strings. The division operator / always returns a float, even when dividing integers evenly. The floor division operator // divides and rounds down to the nearest integer, useful when you need integer results. The modulo operator % returns the remainder after division, often used to check if numbers are even/odd or to cycle through indices. The exponentiation operator ** raises numbers to powers, crucial for mathematical formulas in machine learning.

Here’s how these operators work in practical machine learning scenarios:

# Basic arithmetic operations

training_samples = 800

validation_samples = 200

total_samples = training_samples + validation_samples

print(f"Total dataset size: {total_samples}")

# Division - always returns float

train_split = training_samples / total_samples

print(f"Training split proportion: {train_split}") # 0.8

# Floor division - returns integer

batches = total_samples // 32

print(f"Number of full batches (size 32): {batches}")

# Modulo - remainder after division

remaining_samples = total_samples % 32

print(f"Samples in incomplete batch: {remaining_samples}")

# Exponentiation - useful for formulas

learning_rate = 0.1

decay_rate = 0.9

epoch = 10

decayed_lr = learning_rate * (decay_rate ** epoch)

print(f"Learning rate after {epoch} epochs: {decayed_lr:.6f}")

print()

# Order of operations follows PEMDAS

# Parentheses, Exponentiation, Multiplication/Division, Addition/Subtraction

result = 2 + 3 * 4 ** 2 # 2 + 3 * 16 = 2 + 48 = 50

result_with_parens = (2 + 3) * 4 ** 2 # 5 * 16 = 80

print(f"Without parentheses: {result}")

print(f"With parentheses: {result_with_parens}")Understanding operator precedence (the order in which operations are performed) is crucial. When in doubt, use parentheses to make your intentions explicit. This improves code readability and prevents subtle bugs.

Comparison Operators

Comparison operators compare values and return boolean results (True or False). These are essential for making decisions in your code.

The equality operator == checks if two values are equal. Be careful not to confuse this with the assignment operator =, which assigns a value to a variable. The inequality operator != checks if values are different. The comparison operators <, >, <=, and >= compare magnitudes and work on both numbers and strings (strings are compared alphabetically).

# Comparison operators

model_accuracy = 0.95

threshold = 0.90

# Equality comparison

print(f"Accuracy equals threshold: {model_accuracy == threshold}")

# Greater than comparison

print(f"Accuracy exceeds threshold: {model_accuracy > threshold}")

# Greater than or equal

print(f"Accuracy meets threshold: {model_accuracy >= threshold}")

# Checking if training is complete

current_epoch = 100

max_epochs = 100

training_complete = current_epoch >= max_epochs

print(f"Training complete: {training_complete}")

print()

# Comparing strings

model_type = "CNN"

print(f"Is CNN model: {model_type == 'CNN'}")

print(f"Not RNN model: {model_type != 'RNN'}")Comparison operators are fundamental to control flow—they determine which code executes based on conditions. In machine learning, you constantly make decisions based on comparisons: Has accuracy improved? Is the loss below a threshold? Have we completed enough epochs?

Logical Operators

Logical operators combine boolean values using the principles of Boolean logic. These let you create complex conditions from simpler ones.

The and operator returns True only if both operands are true. This is useful when multiple conditions must all be satisfied. The or operator returns True if at least one operand is true, appropriate when any of several conditions would be acceptable. The not operator inverts a boolean value, turning True into False and vice versa.

# Logical operators for compound conditions

accuracy = 0.92

loss = 0.15

epochs_completed = 50

max_epochs = 100

# AND operator - both conditions must be True

good_performance = (accuracy > 0.9) and (loss < 0.2)

print(f"Model performing well: {good_performance}")

# OR operator - at least one condition must be True

should_continue = (accuracy < 0.95) or (epochs_completed < max_epochs)

print(f"Should continue training: {should_continue}")

# NOT operator - inverts boolean value

early_stop = not should_continue

print(f"Should stop early: {early_stop}")

print()

# Combining multiple logical operators

validation_accuracy = 0.88

training_accuracy = 0.93

overfitting = (training_accuracy > 0.9) and (validation_accuracy < 0.85)

print(f"Model is overfitting: {overfitting}")

# Using parentheses for clarity

complex_condition = (accuracy > 0.9 and loss < 0.2) or (epochs_completed >= max_epochs)

print(f"Complex condition result: {complex_condition}")Logical operators enable sophisticated decision-making. In machine learning pipelines, you might check if a model has converged (low loss AND stable accuracy), if you should save a checkpoint (best accuracy OR specific epoch), or if you should stop training (converged OR maximum iterations reached).

Control Structures: Directing Program Flow

Control structures determine the order in which your code executes. Instead of running line by line from top to bottom, control structures let you make decisions, repeat operations, and skip sections of code based on conditions. Mastering control structures is essential because machine learning involves iterative processes, conditional logic, and repeated operations on data.

Conditional Statements: Making Decisions

Conditional statements let your program make decisions and execute different code depending on whether conditions are true or false. This is how programs adapt their behavior to different situations.

The if statement executes a block of code only when a condition is true. The elif (else if) clause provides alternative conditions to check if the first condition is false. The else clause provides a default action when none of the previous conditions are true.

Understanding how to structure conditionals correctly is crucial. Python uses indentation to define code blocks—all lines indented at the same level after a colon are part of that block. This enforced indentation makes Python code highly readable but means you must be careful with spacing.

# Simple if statement

accuracy = 0.95

if accuracy > 0.9:

print("Excellent model performance!")

print("This model is ready for deployment.")

print()

# if-elif-else chain for multiple conditions

loss = 0.25

if loss < 0.1:

status = "Excellent - very low loss"

elif loss < 0.3:

status = "Good - acceptable loss"

elif loss < 0.5:

status = "Fair - needs improvement"

else:

status = "Poor - requires significant tuning"

print(f"Loss: {loss}")

print(f"Status: {status}")

print()

# Real ML example: deciding whether to save a checkpoint

current_accuracy = 0.93

best_accuracy = 0.91

epoch = 45

save_frequency = 10

if current_accuracy > best_accuracy:

print(f"New best accuracy: {current_accuracy:.2%}")

print("Saving model checkpoint...")

best_accuracy = current_accuracy

elif epoch % save_frequency == 0:

print(f"Regular checkpoint at epoch {epoch}")

print("Saving model checkpoint...")

else:

print("No checkpoint saved this epoch")

print(f"Current best accuracy: {best_accuracy:.2%}")In this example, notice how the conditions are checked in order from most specific to most general. The program first checks if we have a new best accuracy (the most important reason to save). If not, it checks if we’re at a regular save interval. Only if neither condition is true do we skip saving. This pattern of checking specific conditions before general ones is a common programming practice.

Loops: Repeating Operations

Loops execute the same block of code multiple times. This is essential in machine learning where you repeat operations on datasets, train models for multiple epochs, and process batches of data. Python provides two main types of loops, each suited to different situations.

For Loops: Iterating Over Sequences

For loops iterate over sequences—they execute code once for each item in a collection. This is the most common loop in Python because it’s clean, readable, and works with any iterable object (lists, strings, ranges, etc.).

The syntax for item in sequence: assigns each element of the sequence to the variable item in turn, then executes the indented code block. The range() function generates sequences of numbers and is commonly used when you need to repeat something a specific number of times or iterate over indices.

# Basic for loop - training for multiple epochs

num_epochs = 5

print("Training loop:")

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

print(f"Epoch {epoch + 1}/{num_epochs}")

# In real code, training would happen here

print("Training complete!\n")

# Iterating over a list of learning rates

learning_rates = [0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001]

print("Testing different learning rates:")

for lr in learning_rates:

print(f"Training with learning rate: {lr}")

# In real code, would train model and evaluate

print()

# Using enumerate to get both index and value

print("Epoch summary:")

losses = [0.5, 0.3, 0.2, 0.15, 0.12]

for epoch, loss in enumerate(losses):

print(f"Epoch {epoch + 1}: Loss = {loss:.3f}")

if loss < 0.2:

print(" → Good convergence!")

print()

# Nested loops - processing batches within epochs

num_epochs = 3

batches_per_epoch = 4

print("Training with batches:")

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

print(f"\nEpoch {epoch + 1}:")

for batch in range(batches_per_epoch):

print(f" Processing batch {batch + 1}/{batches_per_epoch}")The enumerate() function is particularly useful because it gives you both the index and the value, which you often need when processing sequences. Nested loops let you handle hierarchical structures like epochs containing batches, each containing samples.

While Loops: Repeating Until a Condition Changes

While loops continue executing as long as a condition remains true. They’re useful when you don’t know in advance how many iterations you’ll need—for example, training until convergence rather than for a fixed number of epochs.

# While loop - training until convergence

loss = 1.0

convergence_threshold = 0.1

epoch = 0

max_epochs = 100

print("Training until convergence:")

while loss > convergence_threshold and epoch < max_epochs:

epoch += 1

# Simulate loss decreasing (in real code, this would be actual training)

loss = loss * 0.8

print(f"Epoch {epoch}: Loss = {loss:.4f}")

if loss <= convergence_threshold:

print(f"Converged after {epoch} epochs!")

elif epoch >= max_epochs:

print("Reached maximum epochs without convergence")

print()

# While loop for early stopping based on validation performance

best_val_loss = 1.0

current_val_loss = 1.0

patience = 3

no_improvement_count = 0

epoch = 0

print("Training with early stopping:")

while no_improvement_count < patience and epoch < 20:

epoch += 1

# Simulate validation loss (would be actual evaluation in real code)

current_val_loss = current_val_loss * 0.9 + (epoch * 0.01)

print(f"Epoch {epoch}: Val Loss = {current_val_loss:.4f}")

if current_val_loss < best_val_loss:

best_val_loss = current_val_loss

no_improvement_count = 0

print(" → Improvement! Resetting patience counter.")

else:

no_improvement_count += 1

print(f" → No improvement. Patience: {no_improvement_count}/{patience}")

if no_improvement_count >= patience:

print(f"\nEarly stopping triggered after {epoch} epochs")While loops require careful attention to ensure they eventually terminate. Always include a condition that will eventually become false, or add a maximum iteration counter as a safety measure. The early stopping example demonstrates a common machine learning pattern: continue training while making progress, but stop if performance plateaus.

Loop Control: Break and Continue

Sometimes you need to alter the normal flow of a loop. Python provides two keywords for this: break exits the loop entirely, while continue skips to the next iteration.

# Using break to exit loop early

print("Finding first model above threshold:")

accuracies = [0.75, 0.82, 0.89, 0.94, 0.96, 0.97]

threshold = 0.90

for epoch, acc in enumerate(accuracies, start=1):

print(f"Epoch {epoch}: Accuracy = {acc:.2%}")

if acc >= threshold:

print(f"Reached target accuracy! Stopping at epoch {epoch}.")

break

print()

# Using continue to skip iterations

print("Processing only valid samples:")

samples = [1.5, -2.3, 0.8, None, 3.2, "invalid", 2.1]

for i, sample in enumerate(samples):

# Skip None values and non-numeric values

if sample is None or not isinstance(sample, (int, float)):

print(f"Sample {i}: Skipping invalid data")

continue

# Skip negative values

if sample < 0:

print(f"Sample {i}: Skipping negative value")

continue

# Process valid sample

print(f"Sample {i}: Processing {sample}")The break statement is useful when searching for something—once found, there’s no need to continue. The continue statement helps filter data, skipping invalid entries while processing valid ones. In machine learning, you might use continue to skip corrupt data samples or break to stop training when a convergence criterion is met.

Functions: Organizing Reusable Code

Functions are the primary way to organize code into reusable, logical units. A function is a named block of code that performs a specific task. Instead of writing the same code multiple times, you write it once in a function and call that function whenever you need it. This makes code more maintainable, testable, and understandable.

Defining and Calling Functions

A function definition starts with the def keyword, followed by the function name, parentheses containing any parameters, and a colon. The indented block after the colon is the function body—the code that executes when you call the function. The return statement specifies what value the function produces.

Function names should be descriptive and follow Python’s naming convention: lowercase words separated by underscores (snake_case). Good function names make code self-documenting.

# Simple function without parameters

def greet():

"""Print a greeting message."""

print("Hello from a function!")

print("This code executes every time the function is called.")

# Call the function

greet()

print()

# Function with parameters

def calculate_accuracy(correct_predictions, total_predictions):

"""

Calculate classification accuracy.

Parameters:

correct_predictions (int): Number of correct predictions

total_predictions (int): Total number of predictions

Returns:

float: Accuracy as a value between 0 and 1

"""

if total_predictions == 0:

return 0.0

accuracy = correct_predictions / total_predictions

return accuracy

# Call the function with different arguments

acc1 = calculate_accuracy(85, 100)

acc2 = calculate_accuracy(342, 400)

print(f"Model 1 accuracy: {acc1:.2%}")

print(f"Model 2 accuracy: {acc2:.2%}")

print()

# Function with multiple return values

def train_model(epochs, learning_rate):

"""

Simulate training a model.

Returns:

tuple: (final_accuracy, final_loss)

"""

# Simulated training (real code would actually train)

accuracy = 0.7 + (epochs * 0.02)

loss = 1.0 - (epochs * 0.08)

return accuracy, loss

# Unpack multiple return values

final_acc, final_loss = train_model(epochs=10, learning_rate=0.01)

print(f"Training complete:")

print(f" Final accuracy: {final_acc:.2%}")

print(f" Final loss: {final_loss:.3f}")Notice the docstring (the triple-quoted string immediately after the function definition). Docstrings document what the function does, what parameters it takes, and what it returns. Good documentation is essential, especially in collaborative projects or when you’ll revisit code later.

Default Parameters and Keyword Arguments

Functions can have default parameter values, which are used when the caller doesn’t provide a value. This makes functions more flexible and easier to use for common cases while still allowing customization when needed.

# Function with default parameters

def train_neural_network(layers=3, neurons_per_layer=64, activation='relu',

learning_rate=0.001, epochs=10):

"""

Train a neural network with configurable architecture.

Parameters:

layers (int): Number of hidden layers (default: 3)

neurons_per_layer (int): Neurons in each hidden layer (default: 64)

activation (str): Activation function (default: 'relu')

learning_rate (float): Learning rate (default: 0.001)

epochs (int): Training epochs (default: 10)

"""

print(f"Training neural network:")

print(f" Layers: {layers}")

print(f" Neurons per layer: {neurons_per_layer}")

print(f" Activation: {activation}")

print(f" Learning rate: {learning_rate}")

print(f" Epochs: {epochs}")

print()

# Call with default parameters

print("Using defaults:")

train_neural_network()

# Call with some custom parameters

print("Custom architecture:")

train_neural_network(layers=5, neurons_per_layer=128)

# Call with keyword arguments (order doesn't matter)

print("Custom parameters using keywords:")

train_neural_network(epochs=20, learning_rate=0.01, activation='tanh')Default parameters should be used for values that have sensible defaults but might need customization. Keyword arguments make function calls self-documenting—someone reading train_neural_network(epochs=20) immediately understands what 20 represents, unlike train_neural_network(20).

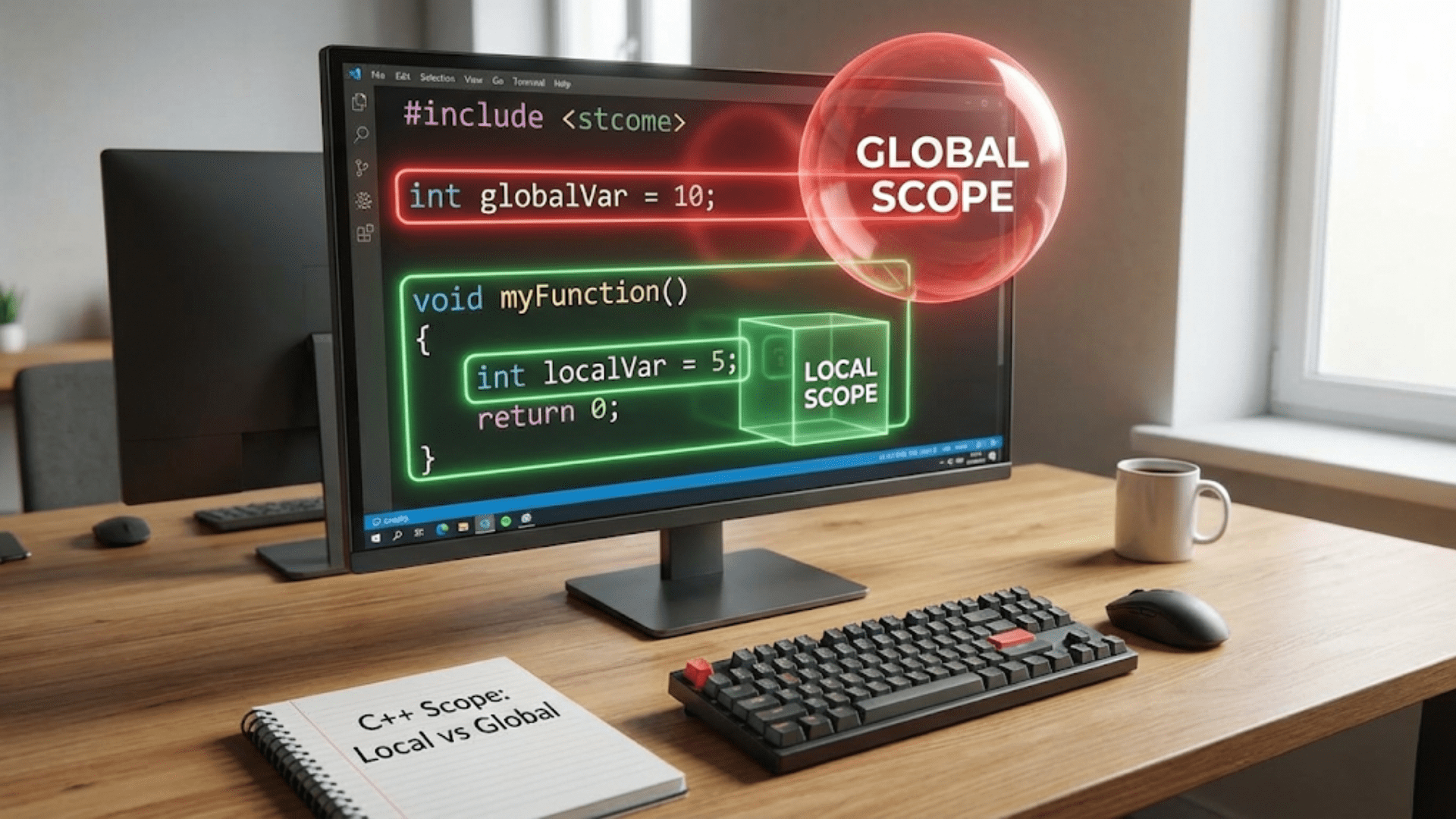

Variable Scope: Understanding Where Variables Exist

Scope determines where in your code a variable can be accessed. Variables defined inside a function have local scope—they only exist within that function. Variables defined outside functions have global scope—they can be accessed anywhere.

Understanding scope prevents bugs and makes code more predictable. As a general rule, avoid modifying global variables inside functions. Instead, pass values as parameters and return results.

# Global variable

model_name = "ResNet50"

def display_model_info():

"""Function accessing global variable."""

print(f"Global model: {model_name}")

def train_model_local():

"""Function with local variable."""

local_loss = 0.5 # This only exists inside the function

print(f"Training with local loss: {local_loss}")

# Cannot access local_loss outside this function

def update_learning_rate(current_lr, decay_factor):

"""Function that doesn't modify global state."""

new_lr = current_lr * decay_factor

return new_lr

# Call functions

display_model_info()

train_model_local()

# Using function that returns values instead of modifying globals

learning_rate = 0.1

print(f"Initial learning rate: {learning_rate}")

for epoch in range(3):

learning_rate = update_learning_rate(learning_rate, decay_factor=0.9)

print(f"Epoch {epoch + 1} learning rate: {learning_rate:.6f}")This example demonstrates good practices: the global variable model_name is only read, not modified. The train_model_local() function uses local variables. The update_learning_rate() function takes inputs and returns outputs rather than modifying global state, making it predictable and testable.

Data Structures: Organizing Collections of Data

Data structures organize multiple values into single, manageable units. Machine learning involves working with large collections of data, making these structures essential. Python provides several built-in data structures, each optimized for different use cases.

Lists: Ordered Collections

Lists are ordered, mutable sequences that can contain any type of object. They’re Python’s most versatile data structure and probably the one you’ll use most frequently in machine learning code.

Lists maintain the order in which elements are added. They can grow or shrink dynamically. You can access elements by index, slice ranges of elements, and modify elements in place. These characteristics make lists perfect for storing sequences like time series data, collections of features, or batches of samples.

# Creating lists

accuracies = [0.82, 0.87, 0.91, 0.94, 0.95]

model_names = ["LogisticRegression", "RandomForest", "NeuralNetwork"]

mixed_list = [100, "epochs", 0.001, True] # Can contain different types

print("Accuracies:", accuracies)

print("Model names:", model_names)

print()

# Accessing elements (indexing starts at 0)

print(f"First accuracy: {accuracies[0]}")

print(f"Last accuracy: {accuracies[-1]}") # Negative indices count from end

print(f"Second to fourth: {accuracies[1:4]}") # Slicing [start:stop]

print()

# Modifying lists

accuracies.append(0.96) # Add to end

print(f"After append: {accuracies}")

accuracies.insert(0, 0.75) # Insert at specific position

print(f"After insert: {accuracies}")

accuracies.remove(0.75) # Remove specific value

print(f"After remove: {accuracies}")

print()

# List operations useful in ML

training_losses = [0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.3, 0.25]

# Find minimum and maximum

best_loss = min(training_losses)

worst_loss = max(training_losses)

print(f"Best loss: {best_loss}, Worst loss: {worst_loss}")

# Find average

average_loss = sum(training_losses) / len(training_losses)

print(f"Average loss: {average_loss:.3f}")

# Check if value exists

if 0.3 in training_losses:

print("Loss of 0.3 found in training history")

print()

# List comprehension - create lists concisely

squared_accuracies = [acc ** 2 for acc in accuracies]

print(f"Original: {accuracies}")

print(f"Squared: {squared_accuracies}")

# Filter with comprehension

high_accuracies = [acc for acc in accuracies if acc > 0.9]

print(f"High accuracies (>0.9): {high_accuracies}")List comprehensions provide a concise way to create lists based on existing lists. The syntax [expression for item in sequence if condition] creates a new list by applying the expression to each item that meets the condition. This is more readable and often faster than using loops to build lists.

Tuples: Immutable Sequences

Tuples are like lists but immutable—once created, they cannot be changed. This immutability provides safety (you can’t accidentally modify values) and enables tuples to be used as dictionary keys.

Tuples are commonly used for fixed collections where the position has meaning, such as coordinates (x, y) or RGB colors (r, g, b). In machine learning, you might use tuples for data shapes, model configurations, or returning multiple values from functions.

# Creating tuples

model_architecture = (784, 128, 64, 10) # Layer sizes: input, hidden1, hidden2, output

image_shape = (224, 224, 3) # Height, width, channels

learning_params = (0.001, 0.9, 100) # Learning rate, momentum, epochs

print(f"Architecture: {model_architecture}")

print(f"Image shape: {image_shape}")

print()

# Accessing tuple elements

input_size = model_architecture[0]

output_size = model_architecture[-1]

print(f"Input size: {input_size}")

print(f"Output size: {output_size}")

print()

# Tuple unpacking

lr, momentum, epochs = learning_params

print(f"Learning rate: {lr}")

print(f"Momentum: {momentum}")

print(f"Epochs: {epochs}")

print()

# Function returning tuple

def get_model_metrics():

accuracy = 0.94

precision = 0.92

recall = 0.96

return accuracy, precision, recall # Returns a tuple

# Unpack returned values

acc, prec, rec = get_model_metrics()

print(f"Metrics - Accuracy: {acc}, Precision: {prec}, Recall: {rec}")The key difference between lists and tuples is mutability. Use lists when you need to modify the collection. Use tuples for fixed collections or when you want to ensure data can’t be changed.

Dictionaries: Key-Value Mappings

Dictionaries store data as key-value pairs. Instead of accessing elements by numeric index like lists, you access values by their associated key. This is incredibly useful for structured data where each value has a meaningful label.

In machine learning, dictionaries are perfect for configuration settings, model parameters, storing results with descriptive names, and organizing data with different types of information about the same entity.

# Creating dictionaries

model_config = {

"name": "ResNet50",

"layers": 50,

"input_shape": (224, 224, 3),

"num_classes": 1000,

"pretrained": True

}

training_results = {

"accuracy": 0.94,

"loss": 0.23,

"epochs": 100,

"best_epoch": 87

}

print("Model configuration:")

for key, value in model_config.items():

print(f" {key}: {value}")

print()

# Accessing values

print(f"Model name: {model_config['name']}")

print(f"Number of layers: {model_config['layers']}")

print(f"Final accuracy: {training_results['accuracy']:.2%}")

print()

# Adding and modifying entries

model_config["optimizer"] = "Adam"

model_config["learning_rate"] = 0.001

model_config["layers"] = 101 # Modify existing value

print("Updated configuration:")

print(model_config)

print()

# Safe access with get() method

batch_size = model_config.get("batch_size", 32) # Returns 32 if key doesn't exist

print(f"Batch size: {batch_size}")

# Check if key exists

if "pretrained" in model_config:

print(f"Using pretrained weights: {model_config['pretrained']}")

print()

# Dictionary comprehension

accuracies = [0.82, 0.87, 0.91, 0.94, 0.95]

epoch_accuracies = {f"epoch_{i+1}": acc for i, acc in enumerate(accuracies)}

print("Epoch accuracies:", epoch_accuracies)Dictionaries provide O(1) average-case lookup time, meaning accessing a value by key is very fast regardless of dictionary size. This makes them excellent for storing configuration parameters or results that you’ll need to access frequently.

Sets: Unique Unordered Collections

Sets store unique elements with no duplicates. They’re unordered, meaning elements don’t have a specific position. Sets are useful for membership testing, removing duplicates, and mathematical set operations.

# Creating sets

unique_labels = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}

training_classes = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

test_classes = {3, 4, 5, 6}

print(f"Unique labels: {unique_labels}")

print(f"Training classes: {training_classes}")

print(f"Test classes: {test_classes}")

print()

# Remove duplicates from list

samples = [1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5]

unique_samples = set(samples)

print(f"Original samples: {samples}")

print(f"Unique samples: {unique_samples}")

print()

# Set operations

common_classes = training_classes & test_classes # Intersection

all_classes = training_classes | test_classes # Union

train_only = training_classes - test_classes # Difference

print(f"Classes in both: {common_classes}")

print(f"All classes: {all_classes}")

print(f"Only in training: {train_only}")

print()

# Membership testing (very fast)

if 5 in test_classes:

print("Class 5 found in test set")

# Practical example: tracking seen samples

processed_ids = set()

all_sample_ids = [101, 102, 103, 101, 104, 102, 105]

print("\nProcessing samples:")

for sample_id in all_sample_ids:

if sample_id in processed_ids:

print(f"Sample {sample_id}: Already processed, skipping")

else:

print(f"Sample {sample_id}: Processing")

processed_ids.add(sample_id)

print(f"\nTotal unique samples processed: {len(processed_ids)}")Sets are particularly valuable when you need to ensure uniqueness or perform set-theoretic operations. In machine learning, you might use sets to track which samples have been processed, find overlapping classes between datasets, or remove duplicate feature names.

Conclusion: Building Your Python Foundation for AI

You have now learned the fundamental building blocks of Python programming. These concepts—variables and data types, operators, control structures, functions, and data structures—form the foundation for all Python code, including sophisticated machine learning applications.

Understanding these basics deeply is more important than rushing to advanced topics. Variables and data types let you represent information in your programs. Operators let you manipulate that information. Control structures let you make decisions and repeat operations. Functions let you organize code into reusable, logical units. Data structures let you manage collections of related data efficiently.

As you continue your journey into machine learning, these concepts will appear constantly. You’ll use lists to store feature vectors, dictionaries to configure models, functions to process data, and loops to iterate through training batches. You’ll use conditionals to implement early stopping, comparison operators to check convergence criteria, and data structures to organize complex information.

The key to mastery is practice. Start writing small programs that use these concepts. Solve simple problems before tackling complex ones. When you encounter unfamiliar code, break it down into these fundamental components. Ask yourself: What variables are being used? What operations are being performed? What control structures direct the flow? What data structures organize the information?

Remember that programming is a skill that improves with deliberate practice. Don’t worry if concepts don’t click immediately—learning to program is like learning a language. Initially, you translate from English to Python in your head. With practice, you begin thinking directly in code, recognizing patterns and solutions naturally.

In the next articles in this series, we’ll build on this foundation, exploring Python libraries essential for machine learning, working with real datasets, and implementing actual machine learning algorithms. But everything you learn will rest on the fundamental concepts covered here. Take the time to understand them thoroughly, experiment with the examples, write your own variations, and you’ll build a solid foundation for your AI development career.