Gradient descent is an iterative optimization algorithm that finds the minimum of a function by repeatedly taking steps in the direction of steepest descent (negative gradient). In machine learning, it minimizes the loss function by adjusting model parameters: computing the gradient of loss with respect to parameters, then updating parameters in the opposite direction of the gradient. The three main variants are batch gradient descent (using all training data per update), stochastic gradient descent (using one example per update), and mini-batch gradient descent (using small batches), each with different speed-accuracy tradeoffs.

Introduction: Finding the Bottom of the Hill

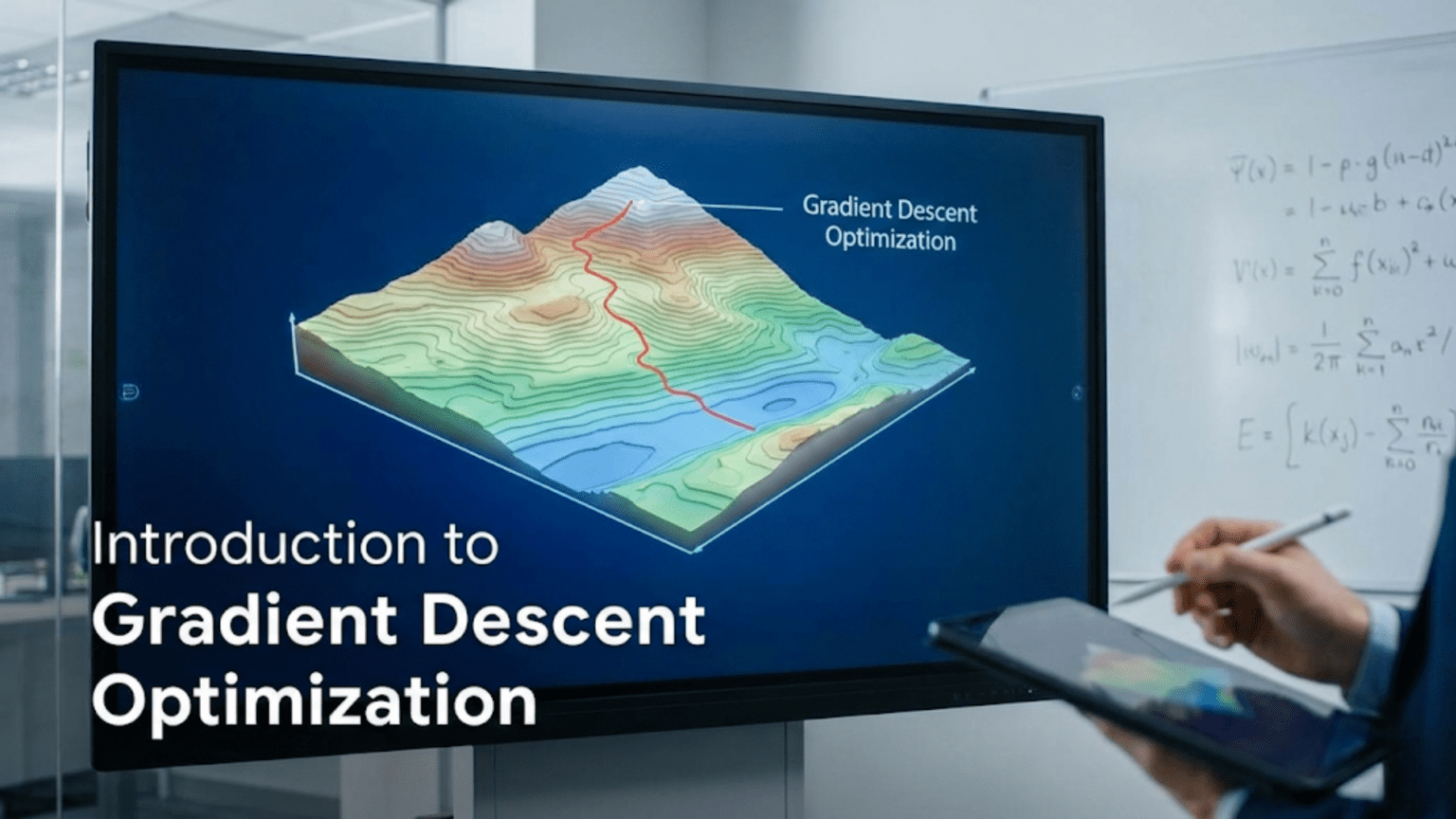

Imagine you’re hiking in dense fog at the top of a mountain. You can’t see where the valley is, but you want to descend to the lowest point. What do you do? You could feel the ground around you to determine which direction slopes downward most steeply, take a step in that direction, then repeat the process. Eventually, you’ll reach a valley—perhaps not the lowest point on the mountain, but at least a local low point.

This is exactly how gradient descent works. It’s a simple yet powerful algorithm for finding the minimum of a function when you can’t see the whole landscape. In machine learning, that function is the loss function, and the minimum represents the best model parameters—the weights and biases that make the most accurate predictions.

Gradient descent is the workhorse of machine learning optimization. Nearly every neural network you’ve heard of—from image classifiers to language models to game-playing agents—was trained using gradient descent or one of its variants. It’s the algorithm that turns backpropagation’s gradient calculations into actual learning, taking those gradients and using them to improve the model step by step.

Understanding gradient descent is essential for anyone working with machine learning. It determines how fast your model trains, whether it will converge to a good solution, and how to diagnose training problems. When you set a learning rate, choose between optimizers, or debug why a model won’t learn, you’re making decisions about how gradient descent operates.

This comprehensive guide introduces gradient descent from the ground up. You’ll learn the core algorithm, mathematical foundations, different variants (batch, stochastic, mini-batch), learning rate selection, advanced optimizers, common challenges and solutions, and practical implementation details.

The Optimization Problem

Before understanding gradient descent, let’s clarify what problem it solves.

The Goal: Minimize Loss

Given:

- Model with parameters θ (weights and biases)

- Loss function L(θ) measuring prediction error

- Training data to learn from

Goal: Find θ that minimizes L(θ)

Mathematical Statement:

θ* = argmin L(θ)

θ

Find parameters θ* that give minimum lossWhy We Need Optimization

Can’t Solve Directly:

- Neural networks: Loss function too complex for analytical solution

- No formula like linear regression’s closed-form solution

- Must use iterative numerical methods

Example:

Linear Regression: Can solve directly

θ = (XᵀX)⁻¹Xᵀy (closed-form solution)

Neural Network: No closed-form solution

Must use iterative optimizationThe Loss Landscape

Visualizing Loss:

- Think of loss as landscape (hills and valleys)

- Height = loss value

- Position = parameter values

- Goal: Find lowest point (valley)

2D Example (one parameter):

Loss

│ ╱‾╲

│ ╱ ╲ ╱‾╲

│ ╱ ╲ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲╱ ╲

│─────────────────────θ

↑ ↑

Local Global

minimum minimumHigh Dimensions:

- Real networks: millions of parameters

- Can’t visualize

- Same principles apply

What is Gradient Descent?

Gradient descent is an iterative algorithm that finds the minimum by repeatedly moving in the direction of steepest descent.

The Core Idea

Step 1: Start at random point (initialize parameters)

Step 2: Calculate gradient (direction of steepest ascent)

∇L(θ) = gradient of loss with respect to parametersStep 3: Move opposite direction (downhill)

θ_new = θ_old - α × ∇L(θ)

Where α = learning rate (step size)Step 4: Repeat until convergence

The Gradient

Definition: Vector of partial derivatives

For parameter vector θ = [θ₁, θ₂, …, θₙ]:

∇L(θ) = [∂L/∂θ₁, ∂L/∂θ₂, ..., ∂L/∂θₙ]Properties:

- Points in direction of steepest increase

- Perpendicular to contour lines of L

- Magnitude indicates steepness

Why Negative Gradient:

- Gradient points uphill (increasing loss)

- Negative gradient points downhill (decreasing loss)

- We want to decrease loss → move in negative gradient direction

Visual Intuition

1D Example:

Loss

│ ╱‾╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ •──→ ╲

│─────────────────θ

↑

Current position

Gradient positive → move left (decrease θ)2D Example (two parameters):

Contour plot of loss:

θ₂│ ╭─╮

│ ╭───╮

│ ╭─────╮

│ ╭───•───╮ • = current position

│ ╭─────────╮

│ ╭───────────╮

└─────────────────θ₁

Gradient points outward (away from minimum)

Negative gradient points inward (toward minimum)

Take step toward centerThe Algorithm: Step-by-Step

Batch Gradient Descent (BGD)

Uses: Entire training dataset for each update

Algorithm:

1. Initialize parameters θ randomly

2. Repeat until convergence:

a. Compute gradient using ALL training data:

∇L(θ) = (1/m) Σᵢ₌₁ᵐ ∇L(θ; xⁱ, yⁱ)

where m = number of training examples

b. Update parameters:

θ = θ - α × ∇L(θ)

c. Check convergence (e.g., gradient small enough)Pseudocode:

# Initialize

theta = random_initialization()

alpha = 0.01 # learning rate

# Repeat until convergence

for iteration in range(max_iterations):

# Compute gradient on entire dataset

gradient = compute_gradient(theta, X_train, y_train)

# Update parameters

theta = theta - alpha * gradient

# Check convergence

if convergence_criterion_met():

breakExample: Linear Regression

Problem: Fit line to data (y = mx + b)

Parameters: θ = [m, b]

Loss: Mean Squared Error

L(θ) = (1/2m) Σᵢ₌₁ᵐ (ŷⁱ - yⁱ)²

= (1/2m) Σᵢ₌₁ᵐ (mxⁱ + b - yⁱ)²

Gradients:

∂L/∂m = (1/m) Σᵢ₌₁ᵐ (mxⁱ + b - yⁱ) × xⁱ

∂L/∂b = (1/m) Σᵢ₌₁ᵐ (mxⁱ + b - yⁱ)Update Rules:

m = m - α × ∂L/∂m

b = b - α × ∂L/∂bNumerical Example:

Data: (x, y) = [(1, 2), (2, 4), (3, 6)]

Initialization: m = 0, b = 0, α = 0.1

Iteration 1:

Predictions: ŷ = [0, 0, 0]

Errors: [−2, −4, −6]

∂L/∂m = (1/3)[(-2)(1) + (-4)(2) + (-6)(3)]

= (1/3)[-2 - 8 - 18] = -28/3 = -9.33

∂L/∂b = (1/3)[-2 - 4 - 6] = -12/3 = -4

Updates:

m = 0 - 0.1 × (-9.33) = 0.933

b = 0 - 0.1 × (-4) = 0.4

New parameters: m=0.933, b=0.4Iteration 2:

Predictions: ŷ = [1.333, 2.266, 3.199]

Errors: [0.667, 1.734, 2.801]

∂L/∂m = (1/3)[(0.667)(1) + (1.734)(2) + (2.801)(3)]

= (1/3)[11.47] = 3.82

∂L/∂b = (1/3)[5.20] = 1.73

Updates:

m = 0.933 - 0.1 × 3.82 = 0.551

b = 0.4 - 0.1 × 1.73 = 0.227

New parameters: m=0.551, b=0.227Continue until convergence…

Final Result: m ≈ 2, b ≈ 0 (true line: y = 2x)

Learning Rate: The Critical Hyperparameter

The learning rate α determines step size. Choosing it correctly is crucial.

Too Small Learning Rate

Problem: Convergence extremely slow

Visual:

Loss

│ ╱‾╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ •→•→•→•→╲

│ ╱ ╲

│─────────────────θ

Tiny steps → thousands of iterationsExample:

α = 0.00001

Takes 100,000 iterations to converge

Training time: hours instead of minutesToo Large Learning Rate

Problem: Overshooting, divergence, oscillation

Visual:

Loss

│ ╱‾╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ • ╲

│ •←──────→•╲

│─────────────────θ

Oscillates, never settlesExample:

α = 10

Jumps over minimum

Loss increases instead of decreases

Training divergesJust Right Learning Rate

Sweet Spot: Converges quickly and smoothly

Visual:

Loss

│ ╱‾╲

│ ╱ ╲

│ ╱ • ╲

│ ╱ • • ╲

│ • ╲

│─────────────────θ

Steady progress toward minimumTypical Values

Neural Networks: 0.001 - 0.1

Common starting point: 0.01

Linear Models: 0.01 - 1.0

Adjust based on:

- Loss behavior

- Gradient magnitudes

- Training stabilityLearning Rate Schedules

Fixed: Same α throughout training

Step Decay: Reduce α periodically

α = α₀ × 0.1^(epoch / drop_every)

Example: α = 0.1 initially, ×0.1 every 10 epochs

Epochs 0-9: α=0.1

Epochs 10-19: α=0.01

Epochs 20-29: α=0.001Exponential Decay:

α = α₀ × e^(-kt)1/t Decay:

α = α₀ / (1 + kt)Adaptive (Adam, RMSprop): Different α per parameter, automatically adjusted

Variants of Gradient Descent

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

Uses: Single random example per update

Algorithm:

1. Initialize θ

2. Repeat until convergence:

For each example (xⁱ, yⁱ) in shuffled training data:

a. Compute gradient on single example:

∇L(θ; xⁱ, yⁱ)

b. Update:

θ = θ - α × ∇L(θ; xⁱ, yⁱ)Advantages:

- Much faster updates: m updates per epoch vs 1 (batch)

- Can escape local minima: Noise helps exploration

- Online learning: Update as data arrives

- Lower memory: Only need one example at a time

Disadvantages:

- Noisy updates: High variance in gradient estimates

- Doesn’t converge exactly: Oscillates around minimum

- Slower overall: Need more iterations to converge

When to Use:

- Very large datasets (millions of examples)

- Online learning scenarios

- When want fast initial progress

Mini-Batch Gradient Descent

Uses: Small batch of examples per update

Algorithm:

1. Initialize θ

2. Repeat until convergence:

For each mini-batch B in shuffled training data:

a. Compute gradient on batch:

∇L(θ) = (1/|B|) Σ_(x,y)∈B ∇L(θ; x, y)

b. Update:

θ = θ - α × ∇L(θ)Batch Sizes: Typically 32, 64, 128, 256

Advantages:

- Balance: Speed of SGD + stability of batch GD

- Vectorization: Efficient matrix operations (GPU-friendly)

- Reduced variance: Smoother than SGD

- Practical: Works well in practice

Disadvantages:

- Hyperparameter: Must choose batch size

- Memory: Requires storing batch

When to Use:

- Default choice for deep learning

- Modern standard for neural networks

Comparison

| Aspect | Batch GD | Stochastic GD | Mini-Batch GD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples per update | All (m) | 1 | B (typically 32-256) |

| Updates per epoch | 1 | m | m/B |

| Convergence | Smooth, stable | Noisy, oscillates | Moderate noise |

| Speed per update | Slow | Very fast | Fast |

| Memory | High (all data) | Very low | Low-moderate |

| GPU utilization | Good | Poor | Excellent |

| Typical use | Small datasets | Rarely (too noisy) | Standard choice |

Advanced Optimizers

Basic gradient descent has limitations. Modern optimizers improve it.

Momentum

Problem: Gradient descent oscillates in ravines

Solution: Add velocity from previous steps

Algorithm:

v = β × v + (1 - β) × ∇L(θ)

θ = θ - α × v

Where:

- v = velocity

- β = momentum coefficient (typically 0.9)Effect:

- Accelerates in consistent directions

- Dampens oscillations

- Faster convergence

Visual:

Without momentum: •→←•→← (oscillates)

With momentum: •→→→→• (smooth)RMSprop (Root Mean Square Propagation)

Problem: Same learning rate for all parameters

Solution: Adaptive learning rate per parameter

Algorithm:

s = β × s + (1 - β) × (∇L(θ))²

θ = θ - α × ∇L(θ) / (√s + ε)

Where:

- s = moving average of squared gradients

- β ≈ 0.9

- ε = small constant (e.g., 10⁻⁸) for numerical stabilityEffect:

- Parameters with large gradients get smaller updates

- Parameters with small gradients get larger updates

- Adaptive per-parameter learning rates

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation)

Combines: Momentum + RMSprop

Algorithm:

m = β₁ × m + (1 - β₁) × ∇L(θ) # First moment (momentum)

v = β₂ × v + (1 - β₂) × (∇L(θ))² # Second moment (RMSprop)

m̂ = m / (1 - β₁ᵗ) # Bias correction

v̂ = v / (1 - β₂ᵗ)

θ = θ - α × m̂ / (√v̂ + ε)

Default: β₁=0.9, β₂=0.999, ε=10⁻⁸Advantages:

- Generally works well “out of the box”

- Adaptive learning rates

- Handles sparse gradients well

- Most popular optimizer for deep learning

When to Use:

- Default choice for most deep learning

- Try first before others

AdaGrad

Idea: Adapt learning rate based on historical gradients

Good for: Sparse data, different feature frequencies

Limitation: Learning rate decays too aggressively

Comparison of Optimizers

| Optimizer | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGD | Simple, well-understood | Slow, needs tuning | Baselines, when have time to tune |

| SGD + Momentum | Faster, dampens oscillations | Still needs tuning | When SGD too slow |

| RMSprop | Adaptive rates, works well | Less common now | RNNs historically |

| Adam | Works well generally, adaptive | Can overfit on small data | Default choice |

| AdaGrad | Good for sparse data | Aggressive decay | NLP with rare words |

Implementation Examples

NumPy: Batch Gradient Descent

import numpy as np

def gradient_descent_batch(X, y, alpha=0.01, iterations=1000):

"""Batch gradient descent for linear regression"""

m, n = X.shape # m examples, n features

theta = np.zeros(n) # Initialize parameters

loss_history = []

for i in range(iterations):

# Predictions

predictions = X @ theta

# Errors

errors = predictions - y

# Gradient (average over all examples)

gradient = (1/m) * (X.T @ errors)

# Update

theta = theta - alpha * gradient

# Track loss

loss = (1/(2*m)) * np.sum(errors**2)

loss_history.append(loss)

# Print progress

if i % 100 == 0:

print(f"Iteration {i}, Loss: {loss:.4f}")

return theta, loss_history

# Example usage

X = np.array([[1, 1], [1, 2], [1, 3]]) # Include bias term

y = np.array([2, 4, 6])

theta, history = gradient_descent_batch(X, y, alpha=0.1, iterations=1000)

print(f"Final parameters: {theta}")NumPy: Mini-Batch Gradient Descent

def gradient_descent_minibatch(X, y, alpha=0.01, epochs=100, batch_size=32):

"""Mini-batch gradient descent"""

m, n = X.shape

theta = np.zeros(n)

for epoch in range(epochs):

# Shuffle data

indices = np.random.permutation(m)

X_shuffled = X[indices]

y_shuffled = y[indices]

# Mini-batches

for i in range(0, m, batch_size):

# Get batch

X_batch = X_shuffled[i:i+batch_size]

y_batch = y_shuffled[i:i+batch_size]

# Gradient on batch

predictions = X_batch @ theta

errors = predictions - y_batch

gradient = (1/len(X_batch)) * (X_batch.T @ errors)

# Update

theta = theta - alpha * gradient

# Epoch loss

all_predictions = X @ theta

loss = (1/(2*m)) * np.sum((all_predictions - y)**2)

if epoch % 10 == 0:

print(f"Epoch {epoch}, Loss: {loss:.4f}")

return theta

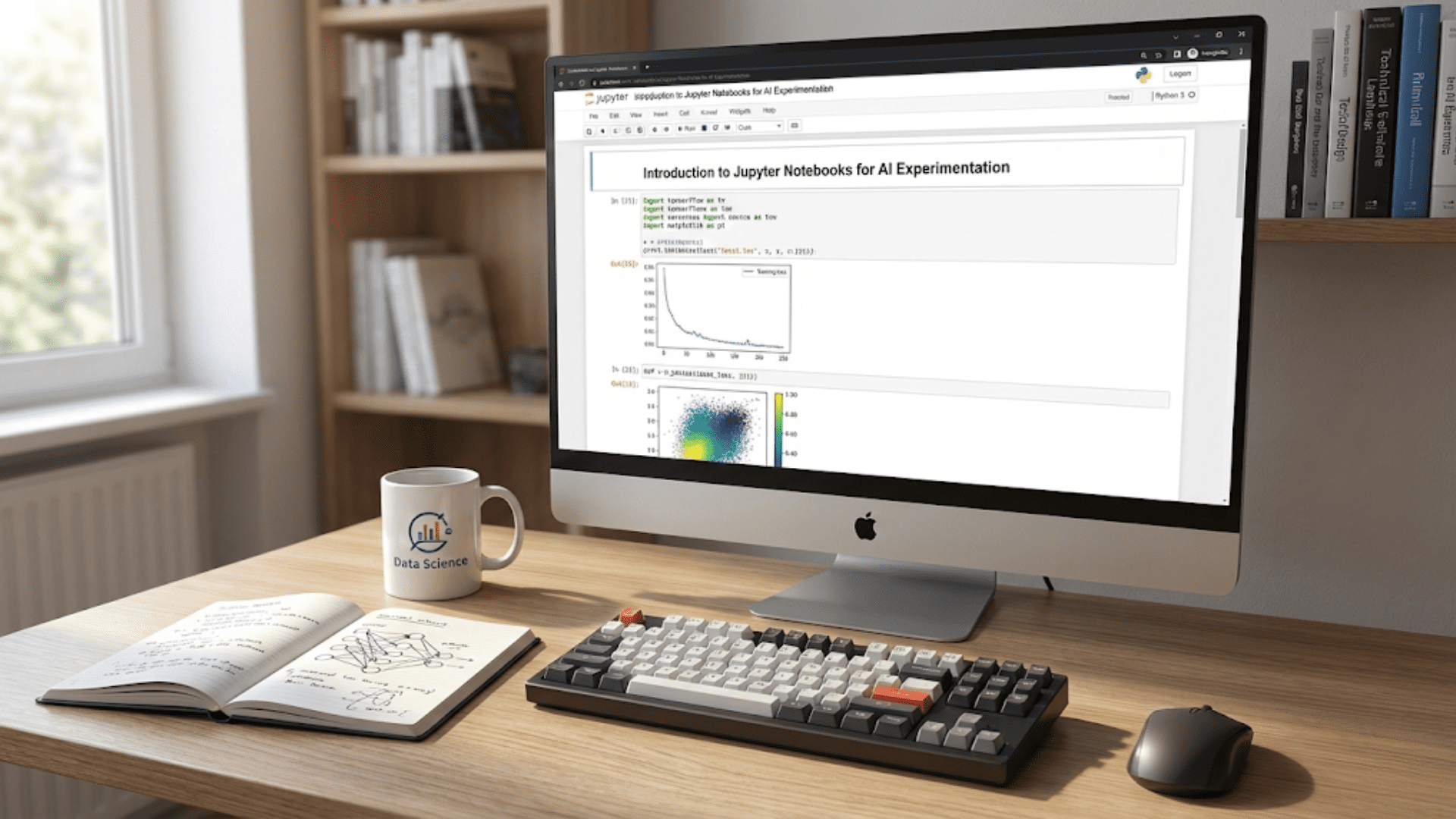

theta = gradient_descent_minibatch(X, y, alpha=0.1, epochs=100, batch_size=2)TensorFlow/Keras: Using Optimizers

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow import keras

# Define model

model = keras.Sequential([

keras.layers.Dense(64, activation='relu', input_shape=(10,)),

keras.layers.Dense(32, activation='relu'),

keras.layers.Dense(1)

])

# Different optimizers

sgd = keras.optimizers.SGD(learning_rate=0.01)

sgd_momentum = keras.optimizers.SGD(learning_rate=0.01, momentum=0.9)

rmsprop = keras.optimizers.RMSprop(learning_rate=0.001)

adam = keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001)

# Compile with optimizer

model.compile(optimizer=adam, loss='mse', metrics=['mae'])

# Train

model.fit(X_train, y_train, epochs=100, batch_size=32,

validation_data=(X_val, y_val))PyTorch: Custom Training Loop

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

# Model

model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(10, 64),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(64, 32),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(32, 1)

)

# Optimizer

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=0.001)

# Training loop

for epoch in range(100):

for X_batch, y_batch in dataloader:

# Forward pass

predictions = model(X_batch)

loss = nn.MSELoss()(predictions, y_batch)

# Backward pass

optimizer.zero_grad() # Clear gradients

loss.backward() # Compute gradients

optimizer.step() # Update parameters

print(f"Epoch {epoch}, Loss: {loss.item():.4f}")Common Challenges and Solutions

Challenge 1: Slow Convergence

Symptoms: Loss decreases very slowly

Solutions:

- Increase learning rate (carefully)

- Use momentum or Adam

- Feature normalization (standardize inputs)

- Better initialization

- Check for bugs (gradient calculation)

Challenge 2: Oscillation/Divergence

Symptoms: Loss jumps around, increases

Solutions:

- Decrease learning rate

- Add gradient clipping

- Check data quality (outliers, errors)

- Use batch normalization

Challenge 3: Getting Stuck in Local Minima

Symptoms: Loss plateaus, not at global minimum

Solutions:

- Use momentum (helps escape)

- Try different initialization

- Add noise (SGD’s stochasticity helps)

- Increase model capacity (make landscape smoother)

Challenge 4: Vanishing/Exploding Gradients

Symptoms: Gradients become too small or too large

Solutions:

- Gradient clipping (cap maximum gradient)

- Proper initialization (Xavier, He)

- Batch normalization

- ReLU activation (vs sigmoid/tanh)

- Residual connections

Monitoring Gradient Descent

What to Track

1. Loss Curves:

plt.plot(train_loss, label='Training')

plt.plot(val_loss, label='Validation')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.legend()Good: Both decreasing smoothly Bad: Training decreases, validation increases (overfitting)

2. Gradient Norms:

grad_norm = np.linalg.norm(gradients)

print(f"Gradient norm: {grad_norm}")Too small: Vanishing gradients Too large: Exploding gradients

3. Parameter Updates:

update_ratio = np.linalg.norm(updates) / np.linalg.norm(parameters)

print(f"Update ratio: {update_ratio}")Ideal: ~0.001 (updates about 0.1% of parameter values)

4. Learning Rate: Track if using schedule or adaptive methods

Practical Tips

1. Start with Adam

optimizer = Adam(learning_rate=0.001)Works well for most problems, good default choice.

2. Normalize Inputs

X = (X - X.mean(axis=0)) / X.std(axis=0)Helps gradient descent converge faster.

3. Use Mini-Batches

batch_size = 32 # or 64, 128, 256Good balance of speed and stability.

4. Monitor Training

Plot losses, check for:

- Steady decrease (good)

- Oscillation (reduce learning rate)

- Plateau (may need different architecture)

5. Learning Rate Finder

# Try range of learning rates

for lr in [1e-5, 1e-4, 1e-3, 1e-2, 1e-1]:

test_optimizer(lr)

# Use one that decreases loss fastest without divergingConclusion: The Engine of Learning

Gradient descent is the optimization algorithm that powers machine learning. By iteratively computing gradients and taking steps in the direction that reduces loss, it enables models to learn from data—adjusting millions or billions of parameters to minimize prediction errors.

Understanding gradient descent means grasping:

The core principle: Follow the negative gradient (direction of steepest descent) to find lower loss, repeating until convergence.

The variants: Batch (stable but slow), stochastic (fast but noisy), mini-batch (practical balance).

The learning rate: The critical hyperparameter determining step size—too small and training is slow, too large and it diverges.

The modern optimizers: Momentum, RMSprop, and Adam that enhance basic gradient descent with adaptive learning rates and velocity.

The challenges: Local minima, saddle points, vanishing/exploding gradients, and how to address them.

Every time you train a machine learning model, gradient descent is working behind the scenes: computing gradients via backpropagation, updating parameters, gradually improving predictions. The loss curves you watch decrease during training show gradient descent in action, finding better and better parameter values.

As you build and train models, remember that choosing the right optimizer, setting appropriate learning rates, and monitoring gradient descent’s progress are critical for success. Adam works well as a default, but understanding the principles enables you to diagnose problems, tune hyperparameters effectively, and ultimately train better models.

Gradient descent might be conceptually simple—calculate gradient, take step, repeat—but this simple algorithm is what makes machine learning work, enabling the remarkable AI systems we see today.