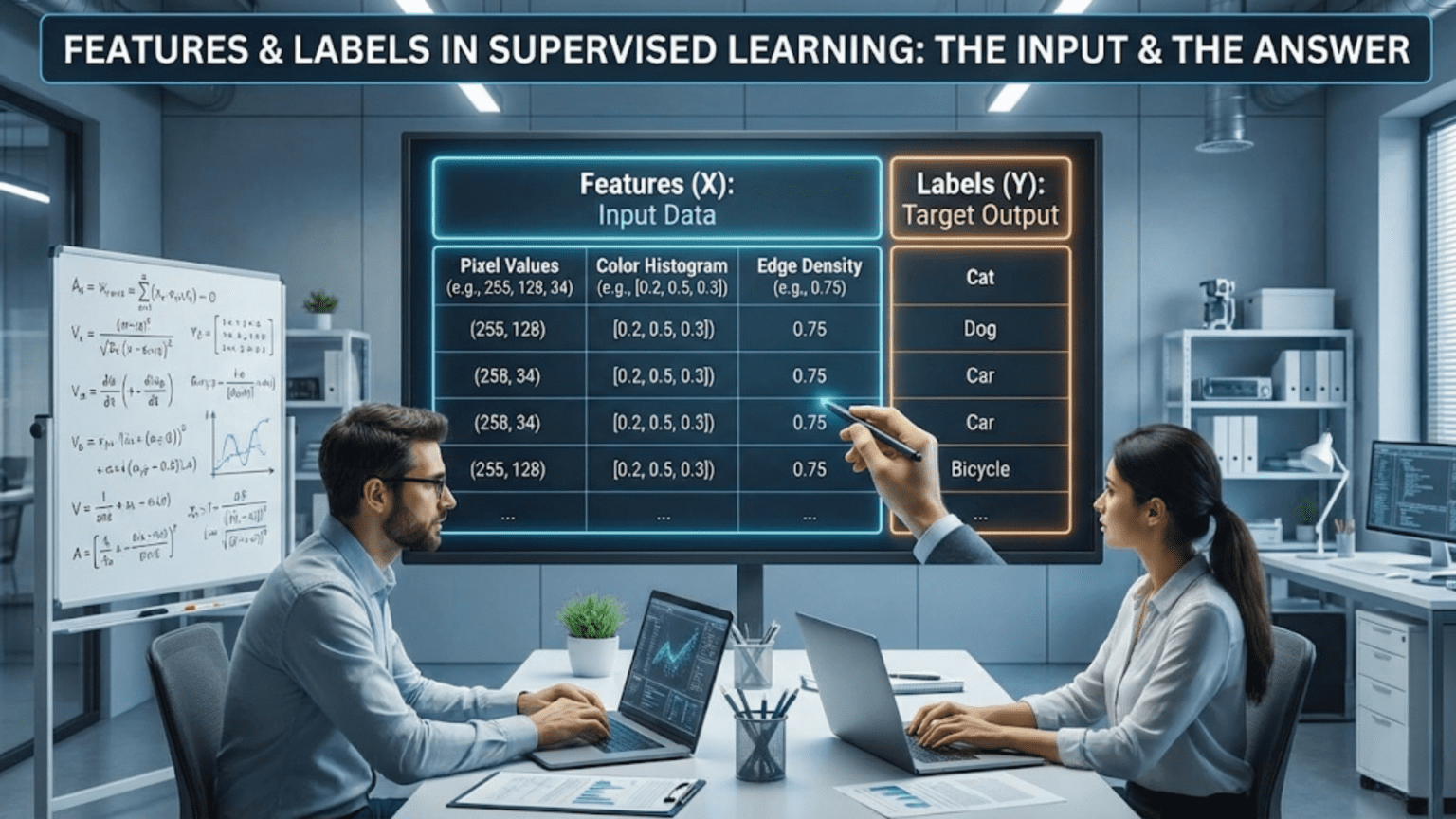

In supervised learning, features are the input variables or characteristics used to make predictions, while labels are the output values or target variables we want to predict. Features represent what the model learns from (like square footage and location for house prices), while labels represent what the model learns to predict (like the actual house price). Together, they form the labeled training examples that enable supervised learning algorithms to discover patterns and make accurate predictions.

Introduction: The Foundation of Supervised Learning

Imagine teaching someone to identify different types of fruits. You would show them examples—pointing out characteristics like color, shape, size, and texture—and tell them the name of each fruit. The characteristics you highlight are features: observable properties that help distinguish one fruit from another. The fruit names are labels: the answers you’re teaching them to identify.

Supervised learning works exactly the same way. Features and labels are the fundamental building blocks that enable computers to learn from examples. Features provide the information the model uses to make predictions, while labels provide the correct answers during training. Understanding these concepts deeply is crucial because the quality of your features and labels largely determines your model’s success—often more than the choice of algorithm itself.

This comprehensive guide explores features and labels in depth. You’ll learn what they are, how to identify them, how to engineer better features, common challenges and solutions, and best practices used by practitioners. Whether you’re building your first machine learning model or looking to deepen your understanding, mastering features and labels is essential for supervised learning success.

What Are Features? The Input Side of Learning

Features, also called input variables, predictors, independent variables, or attributes, are the measurable properties or characteristics that describe your data. They’re the information available to your model for making predictions.

The Anatomy of Features

Think of features as the questions you can ask about each example in your dataset. For a house price prediction model, you might ask:

- How many square feet is the house?

- How many bedrooms does it have?

- What neighborhood is it in?

- How old is the house?

- What’s the school district rating?

Each of these questions represents a feature. The answers to these questions for a specific house constitute that house’s feature values.

Features can be represented mathematically as a vector. If you have five features, each house is represented as a point in five-dimensional space. The model learns patterns in this multi-dimensional feature space that correlate with the target variable.

Types of Features

Features come in different types, each requiring different handling:

Numerical Features

Numerical features represent quantitative measurements with meaningful mathematical relationships.

Continuous Features: Can take any value within a range

- House square footage: 1,234.5 sq ft

- Temperature: 72.3°F

- Account balance: $15,432.18

- Time duration: 3.7 hours

Discrete Features: Take specific, countable values

- Number of bedrooms: 3

- Customer age: 45 years

- Product rating: 4 stars

- Number of purchases: 12

Numerical features have natural ordering and mathematical operations make sense—you can calculate averages, find differences, and compare magnitudes.

Categorical Features

Categorical features represent discrete categories or groups without inherent numerical meaning.

Nominal Categories: No inherent order

- Product category: Electronics, Clothing, Books, Food

- Color: Red, Blue, Green, Yellow

- City: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago

- Payment method: Credit Card, Debit Card, PayPal

Ordinal Categories: Have meaningful order

- Education level: High School < Bachelor’s < Master’s < PhD

- T-shirt size: Small < Medium < Large < XL

- Customer satisfaction: Very Unsatisfied < Unsatisfied < Neutral < Satisfied < Very Satisfied

- Priority: Low < Medium < High < Critical

While ordinal features have order, the distances between levels may not be equal or meaningful numerically.

Binary Features

Binary features have exactly two possible values, often representing yes/no or true/false conditions:

- Has garage: Yes/No

- Email verified: True/False

- Premium member: 1/0

- Clicked ad: Yes/No

Binary features are a special case of categorical features but are often handled differently due to their simplicity.

Text Features

Text features contain unstructured text data:

- Product descriptions

- Customer reviews

- Email content

- Social media posts

- Support ticket messages

Text requires special processing to convert into numerical representations that algorithms can use.

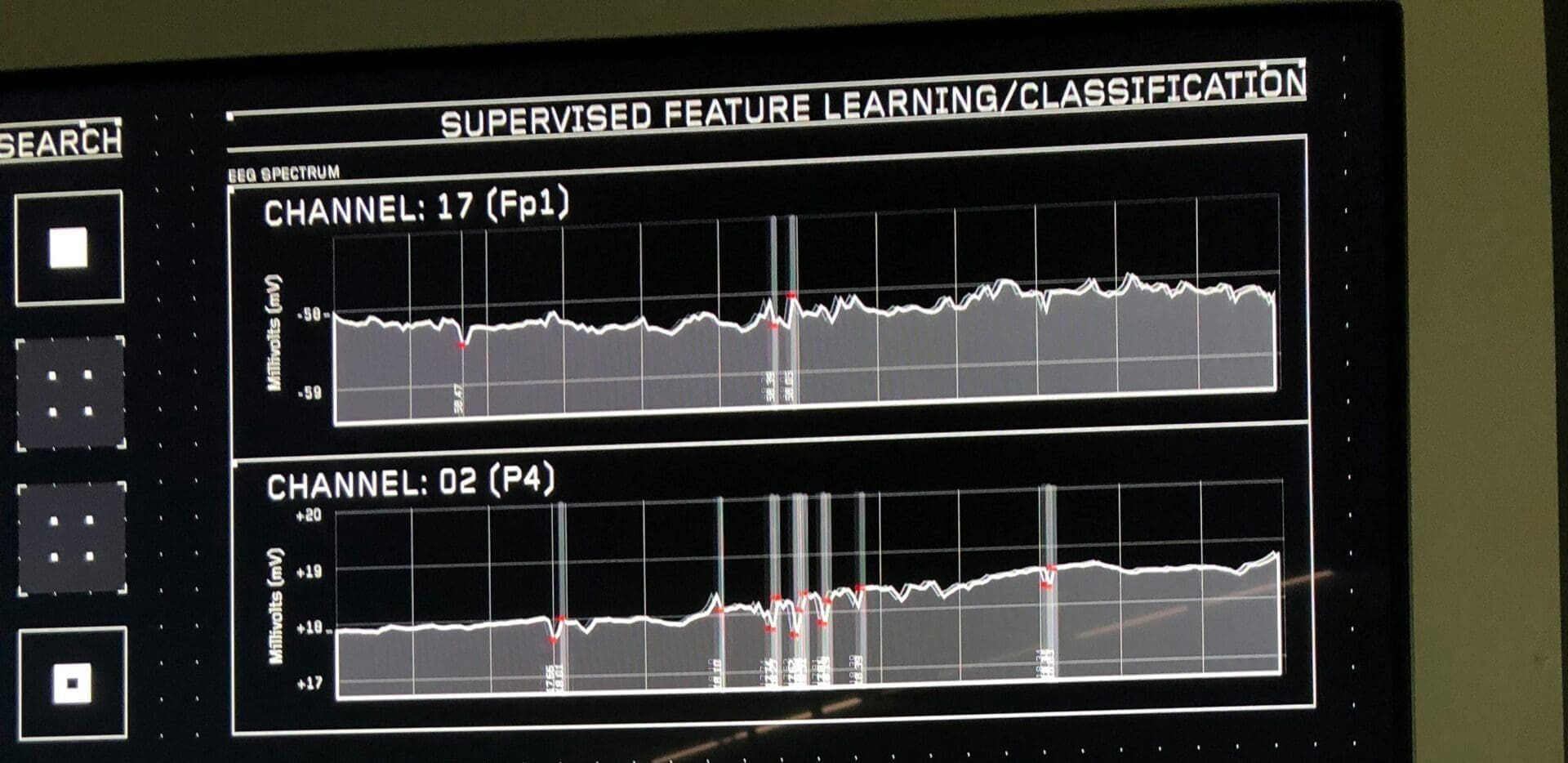

Temporal Features

Temporal features involve time:

- Purchase timestamp: 2024-06-15 14:30:00

- Account creation date: 2022-03-10

- Last login time: 2024-06-14 09:15:22

- Event duration: 45 minutes

Time features often need special handling to extract useful patterns like day of week, seasonality, or time elapsed.

Image Features

For computer vision tasks, images themselves are features:

- Raw pixels values

- Image metadata (size, format, color depth)

- Extracted features (edges, textures, shapes)

Images require specialized processing through convolutional neural networks or feature extraction techniques.

Feature Representation

Different feature types require different representations for machine learning:

Direct Numerical Encoding: Continuous and discrete numerical features can be used directly (though often benefit from scaling).

One-Hot Encoding: Converts categorical variables into binary columns, one for each category.

Example: Color feature with values {Red, Blue, Green}

Original: One-Hot Encoded:

Red → Red=1, Blue=0, Green=0

Blue → Red=0, Blue=1, Green=0

Green → Red=0, Blue=0, Green=1Label Encoding: Assigns integers to categories.

Example: Size {Small, Medium, Large} → {0, 1, 2}

This works for ordinal features but can mislead algorithms into assuming mathematical relationships for nominal features.

Target Encoding: Replaces categories with statistics of the target variable for that category.

Example: Average house price by neighborhood

Embedding: Dense vector representations of categories, learned during training. Common for high-cardinality categorical features or text.

Feature Quality: What Makes a Good Feature?

Not all features are equally valuable. Good features share certain characteristics:

Relevance: Features should be related to the target variable. Irrelevant features add noise without signal.

Example: For predicting house prices, square footage is highly relevant; the seller’s favorite color is not.

Predictive Power: Features should help distinguish between different outcomes.

Example: For spam detection, the presence of words like “viagra” or “winner” is highly predictive; common words like “the” are not.

Availability: Features must be available both during training and when making predictions in production.

Example: You can’t use “whether the customer churned” to predict churn—that’s what you’re trying to predict. You need features available before the churn event.

Measurability: Features should be objectively and consistently measurable.

Example: “House condition” rated by inspectors is more consistent than subjective opinions that might vary wildly.

Minimal Missing Data: Features with many missing values are less useful and complicate training.

Independence: While some correlation is natural, features shouldn’t be purely redundant. Highly correlated features provide duplicate information.

Example: Including both “square footage in feet” and “square footage in meters” adds redundancy.

Stability: Features shouldn’t change their meaning or distribution drastically over time.

Example: A feature based on a specific promotion is less stable than fundamental customer behavior patterns.

What Are Labels? The Output Side of Learning

Labels, also called target variables, response variables, dependent variables, or outputs, represent what you want to predict. Labels are the “correct answers” provided during training that enable the model to learn.

Understanding Labels

If features answer “what information do we have?”, labels answer “what do we want to know?”. Labels define the learning objective.

For supervised learning, you need labeled training data—examples where both the features and the corresponding label are known. The model learns the relationship between features and labels, then applies this learned relationship to predict labels for new examples where only features are known.

Types of Prediction Tasks Based on Labels

The nature of your labels determines what type of supervised learning problem you have:

Classification Labels

Classification labels represent discrete categories or classes. The model learns to assign examples to one of these predefined categories.

Binary Classification: Two possible labels

- Spam detection: {Spam, Not Spam}

- Loan approval: {Approve, Deny}

- Disease diagnosis: {Positive, Negative}

- Fraud detection: {Fraudulent, Legitimate}

- Customer churn: {Will Churn, Won’t Churn}

Multi-Class Classification: More than two mutually exclusive labels

- Handwritten digit recognition: {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}

- Sentiment analysis: {Positive, Neutral, Negative}

- Product categorization: {Electronics, Clothing, Books, Food, Toys}

- Animal identification: {Dog, Cat, Bird, Fish, Horse}

Multi-Label Classification: Multiple labels can apply simultaneously

- Movie genres: {Action, Comedy, Drama, Romance} (a movie can be multiple)

- Document tagging: {Politics, Economy, International, Sports}

- Medical symptoms: {Fever, Cough, Headache, Fatigue}

Regression Labels

Regression labels represent continuous numerical values. The model learns to predict a number on a continuous scale.

Price Prediction:

- House prices: $325,000

- Stock prices: $142.58

- Product pricing: $29.99

Measurement Prediction:

- Temperature forecast: 72.5°F

- Sales volume: 1,247 units

- Customer lifetime value: $2,345.67

Time Prediction:

- Delivery time: 2.3 hours

- Patient recovery time: 14.5 days

- Machine failure time: 87.2 hours

Count Prediction:

- Website visitors: 15,432

- Product demand: 892 units

- Support tickets: 47

While counts are discrete, regression is often used when the range is large and treating it as continuous is reasonable.

Label Quality and Consistency

Label quality critically impacts model performance:

Accuracy: Labels must be correct. Mislabeled examples teach the model incorrect patterns.

Example: A spam filter trained on data where legitimate emails were mistakenly labeled as spam will learn to block good emails.

Consistency: The same features should map to the same label. Inconsistent labeling confuses the model.

Example: If identical houses in the same neighborhood have wildly different price labels due to data errors, the model cannot learn reliable patterns.

Completeness: All training examples need labels. Missing labels reduce the amount of data available for learning.

Objectivity: Labels should be based on objective criteria rather than subjective opinions when possible.

Example: “Customer satisfaction score” from a standardized survey is more objective than “employee’s impression of customer happiness.”

Temporal Validity: Labels should represent the state at the time features were observed.

Example: When predicting customer churn, the churn label should indicate whether they churned in the month following the feature observation, not their current status.

Class Balance: For classification, extremely imbalanced labels (99% one class, 1% another) create training challenges.

The Labeling Process

Obtaining quality labels often requires significant effort:

Natural Labels: Some labels exist naturally in your data

- Purchase amount in transaction data

- Click/no-click in ad logs

- Email marked as spam by users

Manual Labeling: Humans review data and assign labels

- Medical images labeled by radiologists

- Customer service tickets categorized by agents

- Content moderated by human reviewers

Crowdsourcing: Distribute labeling across many people

- Image labeling through platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk

- Content classification by crowd workers

- Sentiment labeling of text

Expert Annotation: Specialists with domain expertise provide labels

- Legal documents classified by lawyers

- Rare disease diagnosis by specialists

- Financial fraud labeled by fraud analysts

Semi-Automated Labeling: Combine automated systems with human review

- Models suggest labels, humans verify

- Flag uncertain cases for human review

- Active learning: query humans on most informative examples

Weak Supervision: Use heuristics, rules, or knowledge bases to generate noisy labels

- Label based on keywords in text

- Use external knowledge bases

- Apply business rules

- Aggregate multiple weak signals

The Relationship Between Features and Labels

Features and labels don’t exist in isolation—understanding their relationship is crucial.

Correlation and Causation

Strong features have high correlation with labels—they provide information about the target. However, remember that correlation doesn’t imply causation.

Useful Correlation: Ice cream sales correlate with drowning deaths (both increase in summer). For predicting drownings, ice cream sales might be predictive even though ice cream doesn’t cause drowning. Temperature is the common cause.

Spurious Correlation: Number of Nicolas Cage movies correlates with swimming pool drownings. This is coincidental and won’t persist.

For practical prediction, correlation can be useful even without causation. But understanding causal relationships helps with:

- Feature engineering: Identifying truly relevant features

- Intervention: Knowing what to change to influence outcomes

- Robustness: Causal features are more stable than coincidental ones

Feature-Label Dependencies

The strength of the relationship between features and labels varies:

Strong Dependencies: Features highly predictive of labels

- Purchase history strongly predicts future purchases

- Credit score strongly predicts loan default

- Symptom combination strongly predicts disease

Weak Dependencies: Features with some predictive power but not definitive

- Weather has some effect on retail sales but isn’t determinative

- Age has some correlation with product preferences but high variance

Conditional Dependencies: Features predictive only in certain contexts

- Income might predict housing choice differently in different cities

- Product features predict satisfaction differently across customer segments

Non-linear Dependencies: Relationships that aren’t simple straight lines

- Learning performance might increase with study time up to a point, then plateau

- Risk might increase exponentially with certain factors

Feature Interactions

Often, combinations of features are more predictive than individual features:

Example: Credit Risk

- Income alone: moderate predictor

- Debt alone: moderate predictor

- Debt-to-income ratio: strong predictor (interaction)

Example: Medical Diagnosis

- Fever alone: many possible causes

- Cough alone: many possible causes

- Fever + cough + fatigue together: more specific diagnosis

Some models (like decision trees) naturally capture interactions. Linear models require explicitly creating interaction features.

Feature Engineering: Creating Better Features

Feature engineering—the art and science of creating informative features—often determines model success more than algorithm choice.

Why Feature Engineering Matters

Raw data rarely comes in the ideal format for machine learning. Feature engineering transforms raw data into representations that make patterns more apparent to algorithms.

Example: Predicting app engagement

Raw features:

- Login timestamps: “2024-06-15 08:30:00”, “2024-06-14 19:45:00”, etc.

Engineered features:

- Days since last login

- Login frequency (logins per week)

- Favorite login time (morning/evening user)

- Weekend vs. weekday usage ratio

- Streak of consecutive days with logins

These engineered features make patterns more obvious to the model.

Domain Knowledge in Feature Engineering

Effective feature engineering requires domain understanding:

Medical Example: Raw lab values might be less informative than:

- Ratios between certain markers

- Rate of change over time

- Deviation from age/gender norms

- Combinations indicating specific conditions

E-commerce Example: Raw clickstream data transformed into:

- Browse-to-purchase conversion rate

- Average time on product pages

- Cart abandonment patterns

- Price sensitivity (discount needed before purchase)

- Favorite shopping times

Domain experts know which relationships matter and which combinations are meaningful.

Common Feature Engineering Techniques

Mathematical Transformations

Transform numerical features to better capture relationships:

Log Transformation: For skewed distributions or multiplicative relationships

- Income, prices, population often benefit from log transformation

- Converts multiplicative relationships to additive ones

Polynomial Features: Capture non-linear relationships

- Add squared or cubed terms: x, x², x³

- Model curves rather than just straight lines

Normalization/Standardization: Scale features to comparable ranges

- Standardization: mean=0, std=1

- Min-max normalization: scale to [0,1]

- Helps algorithms that are sensitive to feature scales

Binning/Discretization: Convert continuous to categorical

- Age → age groups: {18-25, 26-35, 36-50, 51+}

- Useful for capturing non-linear patterns

- Can reduce overfitting by reducing precision

Temporal Features

Extract patterns from timestamps:

Components:

- Hour of day, day of week, month, quarter, year

- Is weekend? Is holiday?

- Season (spring, summer, fall, winter)

Derived Time Features:

- Time since event (days since last purchase)

- Time until event (days until subscription renewal)

- Duration (session length, time between events)

- Velocity (rate of change over time)

Cyclical Encoding: Represent time cyclically

- Hour 23 and hour 0 are close, but numerically far apart

- Use sine/cosine transformations: hour → (sin(2π×hour/24), cos(2π×hour/24))

- Preserves cyclical nature

Text Feature Engineering

Transform text into numerical features:

Bag of Words: Count word frequencies

- Document represented as word count vector

- Simple but loses word order

TF-IDF: Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency

- Weights words by how distinctive they are

- Common words get lower weight, rare words higher

N-grams: Capture word sequences

- Unigrams: individual words

- Bigrams: two-word sequences (“machine learning”)

- Trigrams: three-word sequences

Text Statistics:

- Document length (words, characters)

- Average word length

- Readability scores

- Punctuation patterns

- Capitalization patterns

Embeddings: Dense vector representations

- Word2Vec, GloVe for word embeddings

- Doc2Vec for document embeddings

- Captures semantic relationships

Aggregation Features

Create summary statistics over groups or time windows:

Per-Group Statistics:

- Average purchase by customer

- Maximum temperature by location

- Median income by neighborhood

- Count of transactions per merchant

Time Window Aggregations:

- Sales in last 7 days, 30 days, 90 days

- Moving averages

- Trends (increasing, decreasing, stable)

- Volatility (standard deviation over window)

Ranking Features:

- Percentile ranking within group

- Relative performance vs. peers

- Position in sorted order

Interaction Features

Combine multiple features:

Arithmetic Combinations:

- Ratios: debt/income, price/square_foot

- Differences: current_price – average_price

- Products: length × width = area

Categorical Combinations:

- Combine categories: city + product_category

- Creates finer-grained segments

- Example: “Electronics in New York” vs “Electronics in Rural Areas”

Feature Crosses: Multiply features (especially in linear models)

- Age × income

- Category × price_tier

Encoding Categorical Features

Transform categories into numerical representations:

One-Hot Encoding: Best for nominal categories with moderate cardinality

Color: Red → [1, 0, 0]

Color: Green → [0, 1, 0]

Color: Blue → [0, 0, 1]Label Encoding: For ordinal features or tree-based models

Size: Small → 0

Size: Medium → 1

Size: Large → 2Target Encoding: Use target statistics

City: New York → 325,000 (average house price)

City: Small Town → 180,000 (average house price)Risk: Can leak information and overfit. Use with cross-validation.

Frequency Encoding: Replace with category frequency

Rare categories → low frequency

Common categories → high frequencyBinary Encoding: Represent as binary digits

- More compact than one-hot for high cardinality

- Category_ID 6 → [0, 1, 1, 0] in binary

Hash Encoding: Hash categories to fixed-size vector

- Handles high cardinality and unknown categories

- Multiple categories might hash to same value (collision)

Feature Selection: Choosing the Best Features

Not all features improve models. Too many features can cause:

- Overfitting: Model learns noise instead of signal

- Computational cost: Slower training and inference

- Interpretability loss: Harder to understand model decisions

- Data requirements: More features need more data to avoid overfitting

Feature selection identifies the most valuable features:

Filter Methods

Evaluate features independently before modeling:

Correlation: Features highly correlated with target

# Example: Pearson correlation with target

correlations = df.corr()['target'].sort_values(ascending=False)

selected_features = correlations[correlations.abs() > 0.3].indexStatistical Tests:

- Chi-square test for categorical features

- ANOVA for numerical features

- Mutual information

Variance Threshold: Remove low-variance features

- Features with nearly constant values provide little information

Pros: Fast, simple, model-agnostic Cons: Ignores feature interactions, may miss features useful in combination

Wrapper Methods

Use model performance to evaluate feature subsets:

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE):

- Train model on all features

- Remove least important feature

- Repeat until desired number of features remains

Forward Selection:

- Start with no features

- Add feature that improves model most

- Repeat until performance plateaus

Backward Elimination:

- Start with all features

- Remove feature that hurts model least

- Repeat until performance degrades

Pros: Considers feature interactions, optimized for your model Cons: Computationally expensive, risk of overfitting to validation set

Embedded Methods

Feature selection built into model training:

L1 Regularization (Lasso):

- Penalizes model complexity

- Drives some feature coefficients to exactly zero

- Selected features have non-zero coefficients

Tree-Based Feature Importance:

- Random forests, gradient boosting provide feature importance scores

- Important features used more frequently and earlier in trees

Pros: Efficient (selection during training), considers interactions Cons: Model-specific, may miss features useful for other models

Dimensionality Reduction

Transform features to lower-dimensional space:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA):

- Creates new features (principal components) as linear combinations of originals

- Components capture maximum variance

- Reduces dimensions while preserving information

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA):

- Finds directions that best separate classes

- Supervised dimensionality reduction

Autoencoders:

- Neural networks that learn compressed representations

- Can capture non-linear relationships

Pros: Reduces dimensions effectively, can reveal hidden structure Cons: New features are less interpretable, transformation is fixed

Practical Example: House Price Prediction

Let’s walk through a complete example to solidify understanding.

Problem Definition

Goal: Predict house sale prices

Labels: Sale price (continuous numerical value)

- Range: $100,000 to $2,000,000

- Target for regression task

Raw Features Available

Property Characteristics:

- Square footage: 1,500 sq ft

- Number of bedrooms: 3

- Number of bathrooms: 2.5

- Lot size: 8,000 sq ft

- Year built: 1985

- Garage spaces: 2

- Has pool: No

- Has basement: Yes

- Number of floors: 2

Location Information:

- Address: “123 Main St, Springfield, IL 62701”

- Latitude: 39.7817

- Longitude: -89.6501

- School district: “Springfield District 186”

Transaction Details:

- List date: 2024-03-15

- Sale date: 2024-05-20

- Days on market: 66

Neighborhood Data (from external sources):

- Median income: $52,000

- Crime rate: 3.2 per 1,000

- Average commute time: 24 minutes

Feature Engineering

Transform raw features into more informative representations:

Direct Numerical Features

Use as-is (with possible scaling):

- Square footage

- Lot size

- Number of bedrooms

- Number of bathrooms

- Garage spaces

- Latitude, longitude

Derived Numerical Features

Age Features:

- House age: Current year – year built = 39 years

- Age category: {New, Modern, Established, Historic}

Size Ratios:

- Price per square foot (will be calculated post-sale)

- Interior to lot ratio: sq_footage / lot_size

- Bedrooms per square foot: bedrooms / sq_footage

Location-Based Features:

- Distance to city center: Calculated from lat/long

- Distance to nearest school, park, shopping

- Neighborhood quality score: Composite of income, crime, schools

Time Features:

- Month listed: March (spring market)

- Is peak season: Yes (spring/summer)

- Days on market: 66 (indicates demand)

Categorical Feature Encoding

Binary Features (already binary):

- Has pool: 0 (No)

- Has basement: 1 (Yes)

One-Hot Encoding:

- School district → One column per district

- Neighborhood → One column per neighborhood

Ordinal Encoding:

- Condition rating: {Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent} → {1, 2, 3, 4}

Target Encoding:

- Neighborhood → Average sale price in that neighborhood

- School district → Average sale price for that district

Text Processing

Address Parsing:

- Extract street name, city, state, zip

- Create binary features: Is on Main St? Is in historic district?

School District:

- Extract district name

- Encode as category

- Add school rating from external data

Interaction Features

Combined Features:

- Bedrooms × bathrooms

- Size × location quality

- Age × condition

Geographic Clusters:

- K-means clustering on lat/long creates “neighborhood clusters”

- Properties in same cluster likely have similar values

Feature Selection Results

After engineering 50+ features, we select most important:

Top 15 Features by Importance:

- Square footage

- Neighborhood average price (target encoded)

- School district rating

- Number of bathrooms

- Lot size

- Distance to city center

- House age

- Garage spaces

- Has basement

- Neighborhood income

- Crime rate

- Number of bedrooms

- Month listed

- Days on market

- Has pool

Removed Features:

- Redundant: Both “year built” and “age” (kept age)

- Low variance: All houses in sample have 1-3 floors

- Weak correlation: Specific street names

- Leakage risks: Sale date (future information)

Model Training

With engineered features and selected label:

Training Data:

- 5,000 historical sales

- Features: 15 selected features per house

- Labels: Actual sale prices

Validation Strategy:

- Split by time: Train on 2022-2023, validate on early 2024, test on recent 2024

- Ensures temporal validity

Model Performance:

- Baseline (median price): $280,000 MAE (Mean Absolute Error)

- Linear regression: $45,000 MAE

- Random forest: $32,000 MAE

- Gradient boosting: $28,000 MAE

The gradient boosting model predicts prices within $28,000 on average—much better than simply using median price.

Feature Importance Insights

Analyzing which features the model finds most important:

Most Important:

- Square footage (30% of importance)

- Location-based features (25%)

- Quality indicators (20%)

Least Important:

- Days on market (2%)

- Has pool (1.5%)

Insights:

- Size matters most, as expected

- Location is critical—even similar houses vary by neighborhood

- Condition and features matter, but less than size and location

- Market timing has minimal impact on final price

These insights guide:

- What data to collect for new predictions

- What factors sellers should emphasize

- Where model might be less reliable (unique properties)

Common Challenges and Solutions

Building effective features and labels involves navigating several challenges:

Challenge 1: Data Leakage

Problem: Features contain information not available at prediction time

Example: Using “customer churned” to predict churn, or “claim amount” to predict claim fraud

Solution:

- Carefully audit features for temporal validity

- Ask: “Would this information be available when making real predictions?”

- Use time-based splits for validation

- Document feature creation timing

Challenge 2: High Cardinality Categorical Features

Problem: Categories with thousands of unique values (e.g., user IDs, product IDs)

Example: Product ID with 50,000 different products

Solution:

- Target encoding with regularization

- Embeddings (learn dense representations)

- Feature hashing

- Group rare categories into “Other”

- Use frequency encoding

Challenge 3: Missing Data

Problem: Features or labels have missing values

Example: 30% of customers don’t provide age information

Solution for Features:

- Imputation (mean, median, mode)

- Model-based imputation (predict missing values)

- Create “missing” indicator feature

- Use algorithms that handle missing data (XGBoost)

Solution for Labels:

- Often must remove examples (can’t train without labels)

- Semi-supervised learning (use unlabeled data differently)

- Active learning (strategically label most useful examples)

Challenge 4: Imbalanced Labels

Problem: One class much more common than others

Example: Fraud detection where 99% of transactions are legitimate

Solutions:

- Resampling: Oversample minority class, undersample majority

- Class weights: Penalize errors on minority class more

- Synthetic data: SMOTE generates synthetic minority examples

- Different metrics: F1, precision-recall rather than accuracy

- Anomaly detection approaches

Challenge 5: Label Noise

Problem: Incorrect or inconsistent labels

Example: Human labelers disagree, or data entry errors

Solutions:

- Multiple labelers with agreement voting

- Quality control processes

- Confidence scores from labelers

- Noise-robust algorithms

- Clean data iteratively (use model to find suspicious labels)

Challenge 6: Concept Drift

Problem: Relationship between features and labels changes over time

Example: Customer preferences shift, economic conditions change

Solutions:

- Regularly retrain models

- Monitor feature distributions

- Use time-based features to capture trends

- Adaptive learning algorithms

- A/B test new models before full deployment

Challenge 7: Curse of Dimensionality

Problem: Too many features relative to number of examples

Example: 1,000 features but only 500 training examples

Solutions:

- Feature selection: Keep only most important

- Dimensionality reduction: PCA, autoencoders

- Regularization: Penalize model complexity

- Collect more data

- Use domain knowledge to reduce features

Challenge 8: Feature Engineering for Complex Data

Problem: Raw data is images, audio, video, or other complex formats

Solutions for Images:

- Use pre-trained models (transfer learning)

- Convolutional neural networks

- Hand-crafted features (edges, textures, shapes)

Solutions for Text:

- Word embeddings (Word2Vec, GloVe)

- TF-IDF representations

- Transformer models (BERT)

Solutions for Time Series:

- Temporal features (trends, seasonality)

- Lagged features (previous values)

- Recurrent neural networks

Best Practices for Features and Labels

Successful practitioners follow these guidelines:

For Features

1. Start Simple, Add Complexity Gradually

- Begin with basic features

- Add engineered features if model needs improvement

- Don’t over-engineer before knowing what helps

2. Document Everything

- Record feature definitions clearly

- Note calculation methods and sources

- Explain engineering choices

- Future you will thank present you

3. Validate Feature Quality

- Check distributions (histograms, statistics)

- Look for unexpected values

- Verify consistency across data splits

- Ensure production features match training

4. Consider Production Constraints

- Can features be calculated in real-time?

- What’s the latency of feature computation?

- Are external data sources reliable?

- What happens if data is unavailable?

5. Think About Interpretability

- Can you explain features to stakeholders?

- Are relationships with labels intuitive?

- Can you justify using specific features?

6. Test Feature Importance

- Which features actually matter?

- Remove features that don’t help

- Understand why features are predictive

7. Watch for Leakage

- Extremely careful with temporal features

- Audit for information not available at prediction time

- Test with time-based splits

8. Handle Categorical Features Thoughtfully

- Choose encoding based on cardinality and model type

- Tree-based models: Label encoding often fine

- Linear models: One-hot or target encoding

- High cardinality: Embeddings or hashing

For Labels

1. Ensure Label Quality

- Multiple labelers for validation

- Clear labeling guidelines

- Regular quality audits

- Address disagreements systematically

2. Define Labels Precisely

- What exactly does each label mean?

- How are edge cases handled?

- Document decision boundaries

3. Check Label Distribution

- Are classes balanced?

- Do labels make sense for your data?

- Are there enough examples per class?

4. Validate Temporal Alignment

- Labels reflect appropriate time period

- Match label timing to feature timing

- Consider lead/lag relationships

5. Consider Label Granularity

- Too coarse: Miss important distinctions

- Too fine: Insufficient data per class

- Find appropriate level

6. Plan for Label Evolution

- Can you relabel if definitions change?

- How to handle historical inconsistency?

- Version control for labeling schemes

7. Measure Labeling Agreement

- Inter-rater reliability metrics

- Identify difficult cases

- Improve labeling guidelines based on disagreements

For Feature-Label Relationships

1. Visualize Relationships

- Scatter plots for numerical features vs. labels

- Box plots for categorical features vs. labels

- Correlation matrices

- Helps understand and communicate patterns

2. Test Assumptions

- Don’t assume relationships are linear

- Check for interactions

- Look for non-obvious patterns

3. Domain Expertise Matters

- Collaborate with domain experts

- They know which features should matter

- They can validate model behavior

4. Iterate Based on Results

- Analyze prediction errors

- Engineer features to address weaknesses

- Refine labels if necessary

5. Monitor in Production

- Feature distributions shouldn’t drift dramatically

- Label patterns should remain stable

- Alert on unexpected changes

Comparison: Good vs. Poor Features and Labels

Understanding what makes features and labels effective versus problematic:

| Aspect | Good Features/Labels | Poor Features/Labels |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Directly related to target; logical connection | No clear relationship; arbitrary associations |

| Availability | Available at training and prediction time | Only available after the event; future information |

| Quality | Accurate, consistent, minimal missing | Many errors, inconsistent, mostly missing |

| Predictive Power | Strong correlation with target; clear patterns | Weak signal; mostly noise |

| Stability | Consistent meaning and distribution over time | Meaning changes; unstable distributions |

| Measurability | Objective, reproducible measurements | Subjective, inconsistent measurements |

| Interpretability | Understandable to stakeholders; explainable | Cryptic, hard to explain or justify |

| Independence | Provides unique information | Redundant with other features |

| Cardinality | Appropriate number of unique values | Too many (high cardinality issues) or too few (no variance) |

| Scale | Appropriate range and distribution | Extreme outliers, problematic scales |

Example: Customer Churn Prediction

Good Features:

- Days since last purchase (relevant, available, predictive)

- Customer lifetime value (captures engagement)

- Support ticket count (indicates satisfaction)

- Contract type (affects churn propensity)

Poor Features:

- Customer ID (no predictive power)

- Data entry timestamp (not relevant to churn)

- Whether customer churned (this is the label—leakage!)

- Employee’s personal opinion (subjective, inconsistent)

Good Label:

- Binary: 1 if customer canceled within 30 days after observation, 0 otherwise

- Clear definition, appropriate timeframe, verifiable

Poor Label:

- Vague: “Customer seems unhappy”

- Temporal confusion: Current churn status (not aligned with when features were observed)

- Inconsistent: Different criteria used at different times

Conclusion: The Foundation of Successful Models

Features and labels are the foundation upon which all supervised learning rests. No amount of algorithmic sophistication can compensate for poor features or noisy labels. Conversely, well-engineered features and high-quality labels enable even simple models to perform remarkably well.

Understanding features and labels deeply means:

For Features:

- Recognizing what information is actually available and useful

- Transforming raw data into representations that highlight patterns

- Engineering new features that capture domain knowledge

- Selecting features that balance predictive power with simplicity

- Ensuring features are available and consistent in production

For Labels:

- Defining clearly what you’re trying to predict

- Ensuring label quality through careful collection and validation

- Aligning labels temporally with features

- Handling label noise and imbalance appropriately

- Choosing label granularity that matches your data and goals

For Their Relationship:

- Understanding how features correlate with labels

- Identifying interactions and non-linear patterns

- Avoiding data leakage that inflates performance estimates

- Iterating on features based on model performance

- Validating that learned relationships make domain sense

The journey from raw data to effective features and labels requires:

- Domain expertise to identify what matters

- Technical skills to engineer and encode features

- Statistical understanding to evaluate relationships

- Engineering discipline to ensure production readiness

- Iterative refinement based on results

Remember that feature engineering is often where data scientists add the most value. While AutoML systems can automate algorithm selection and hyperparameter tuning, creating meaningful features from raw data still largely requires human insight and creativity. The best features come from understanding both the data and the problem domain deeply.

As you build supervised learning systems, invest time in features and labels. Clean your data thoroughly. Engineer features thoughtfully. Validate label quality rigorously. These foundational elements determine how well your models can learn and ultimately how much value they deliver.

Start with simple features, evaluate their impact, and add complexity only when it improves results. Document your decisions. Test assumptions. Learn from errors. The craft of feature engineering and label definition improves with practice and experience. Each project teaches lessons about what works and what doesn’t, building your intuition for effective feature design.

Features and labels might seem like simple concepts—just inputs and outputs—but their thoughtful construction separates successful machine learning projects from failed ones. Master these fundamentals, and you’ve laid the groundwork for building powerful, reliable supervised learning systems.