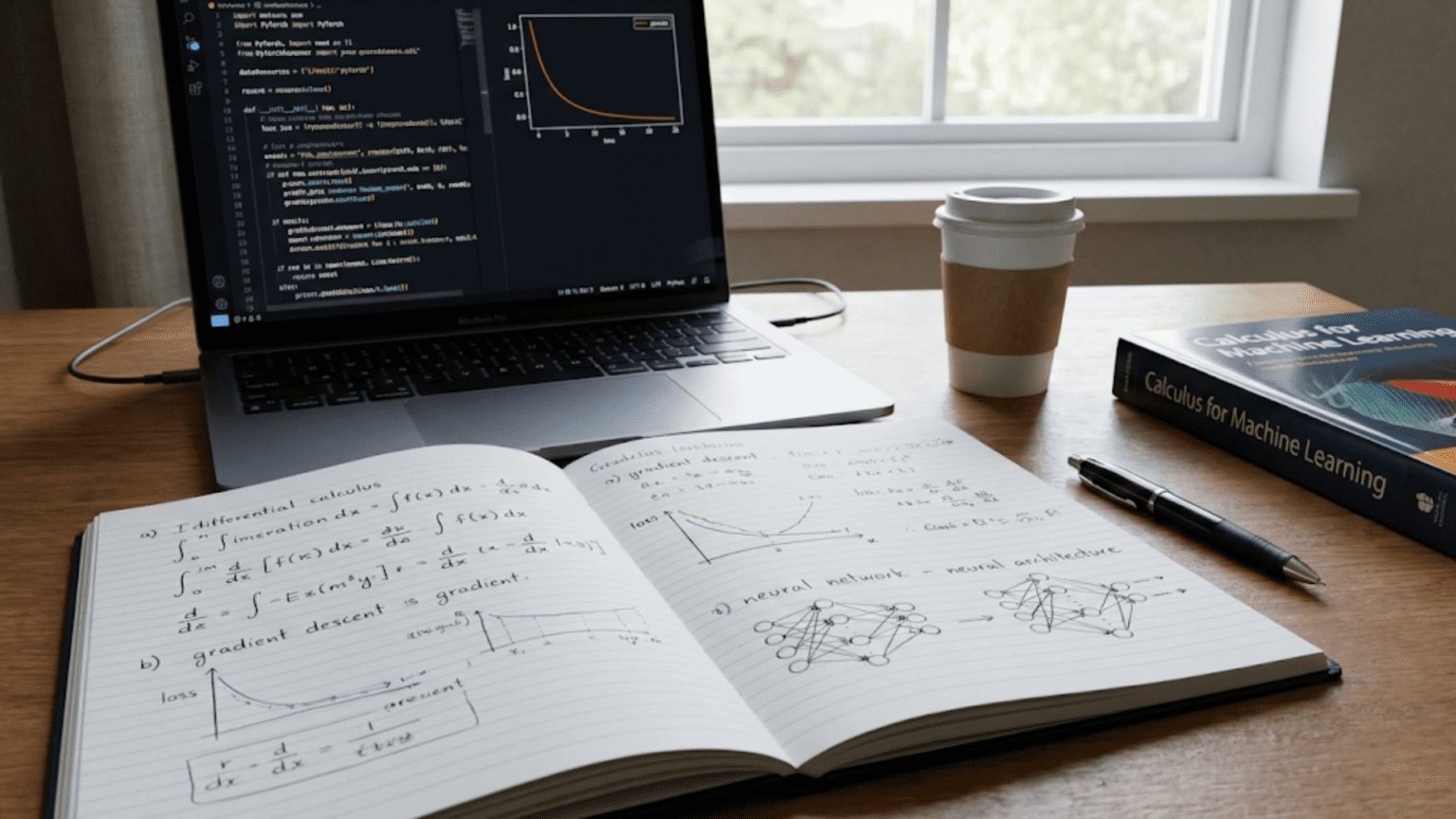

When people say “you need calculus for machine learning,” they often make it sound like you need years of advanced mathematical training. The mention of derivatives, integrals, and differential equations can trigger anxiety in anyone who struggled with math in school or hasn’t thought about calculus in years.

Here’s the reality: you don’t need to master all of calculus to understand and work with machine learning. You need to understand a specific subset of calculus concepts—primarily derivatives and their applications. Even better, you don’t need to compute derivatives by hand (computers do that). What matters is understanding what derivatives tell you and how they’re used in machine learning.

The core idea is simple: calculus helps us understand how things change. In machine learning, we’re constantly asking “if I adjust this parameter slightly, how does my model’s error change?” This is a calculus question, and the answer guides how we train models. Understanding this process transforms machine learning from a mysterious black box into a logical, comprehensible procedure.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll build your understanding of the calculus concepts that matter for AI. We’ll focus on intuition over formalism, on applications over abstract theory, and on the “why” rather than just the “what.” By the end, you’ll understand the mathematical foundation that makes machine learning work.

Why Calculus Matters for Machine Learning

Before diving into specific concepts, let’s establish why calculus is so fundamental to AI.

The Central Problem: Optimization

Machine learning is fundamentally an optimization problem. We have:

- A model with adjustable parameters (weights in a neural network, coefficients in linear regression)

- A loss function measuring how wrong the model’s predictions are

- A goal: Adjust parameters to minimize loss

The question becomes: How do we adjust parameters to improve the model?

This is where calculus enters. Calculus tells us:

- Which direction to adjust parameters (increase or decrease)

- How much each parameter affects the loss

- How quickly we can improve

The Derivative: Rate of Change

The derivative measures how one quantity changes with respect to another. If you have a function y = f(x), the derivative tells you how much y changes when x changes slightly.

Practical meaning in ML:

- “If I increase this weight by 0.01, how much does the loss change?”

- “Which weights have the biggest impact on model performance?”

- “Am I moving in the right direction to reduce error?”

These are all questions about rates of change—derivative questions.

From Derivatives to Learning

The learning process in machine learning:

- Compute predictions using current parameters

- Calculate loss (how wrong predictions are)

- Compute derivatives (how loss changes with each parameter)

- Update parameters in the direction that reduces loss

- Repeat thousands of times

Steps 3 and 4 rely entirely on calculus. Without derivatives, we couldn’t train models effectively.

Understanding Derivatives: The Foundation

Let’s build intuition for what derivatives actually mean, starting from the ground up.

The Slope Connection

Remember slope from algebra? Slope measures steepness: how much y changes when x changes.

slope = rise / run = Δy / Δx

A derivative is essentially a slope, but for curves rather than straight lines. It’s the “instantaneous slope”—the slope at a specific point.

Intuitive Example: Position and Velocity

Imagine you’re driving. Your position changes over time. Velocity is the derivative of position—it tells you how fast position is changing.

- Position: How far you’ve traveled

- Velocity (derivative): How quickly position is changing (miles per hour)

- Acceleration (second derivative): How quickly velocity is changing

If your position is y = f(t) where t is time:

- First derivative: dy/dt = velocity

- Second derivative: d²y/dt² = acceleration

Graphical Interpretation

Look at a curve. The derivative at any point is the slope of the line tangent to the curve at that point.

Example: y = x²

At x = 2:

- The function value: y = 4

- The derivative: dy/dx = 4

- Meaning: If x increases from 2 to 2.01, y increases by approximately 4 × 0.01 = 0.04

The derivative tells you the rate of change at that specific point.

Positive vs Negative Derivatives

- Positive derivative: Function is increasing (going up)

- Negative derivative: Function is decreasing (going down)

- Zero derivative: Function is flat (local minimum or maximum)

In machine learning, we look for parameters where the loss derivative is zero (or close to zero)—these are optimal points where loss is minimized.

Common Derivatives You’ll Encounter

Let’s look at derivatives of functions commonly used in machine learning.

Power Functions

For f(x) = xⁿ:

f'(x) = n × x^(n-1)

Examples:

- f(x) = x² → f'(x) = 2x

- f(x) = x³ → f'(x) = 3x²

- f(x) = x → f'(x) = 1

In ML: Loss functions often involve squared terms (x²), so we frequently encounter derivatives like 2x.

Exponential Function

For f(x) = eˣ:

f'(x) = eˣ

The exponential function is its own derivative!

In ML: Used in softmax function for classification, in certain activation functions.

Natural Logarithm

For f(x) = ln(x):

f'(x) = 1/x

In ML: Log loss functions use logarithms, requiring this derivative.

Constant Multiple Rule

If f(x) = c × g(x) where c is a constant:

f'(x) = c × g'(x)

Example: f(x) = 5x² → f'(x) = 5 × 2x = 10x

Sum Rule

If f(x) = g(x) + h(x):

f'(x) = g'(x) + h'(x)

Example: f(x) = x² + x³ → f'(x) = 2x + 3x²

Derivatives of sums are sums of derivatives—convenient for complex functions!

Product Rule

If f(x) = g(x) × h(x):

f'(x) = g'(x) × h(x) + g(x) × h'(x)

Example: f(x) = x² × x³ = x⁵

- Using product rule: f'(x) = 2x × x³ + x² × 3x² = 2x⁴ + 3x⁴ = 5x⁴

- Using power rule directly: f'(x) = 5x⁴ ✓

Both give the same answer!

The Chain Rule: Composing Functions

The chain rule is arguably the most important calculus concept for machine learning. It tells us how to find derivatives of composite functions—functions inside functions.

Understanding Composition

A composite function is one function applied to another:

f(g(x))

Example: h(x) = (x² + 1)³

This is the composition of:

- Inner function: g(x) = x² + 1

- Outer function: f(u) = u³

- Combined: h(x) = f(g(x)) = (x² + 1)³

The Chain Rule Formula

For h(x) = f(g(x)):

h'(x) = f'(g(x)) × g'(x)

In words: “derivative of outer function (evaluated at inner function) times derivative of inner function”

Chain Rule Example

Find the derivative of h(x) = (x² + 1)³

Step 1: Identify inner and outer functions

- Inner: g(x) = x² + 1, so g'(x) = 2x

- Outer: f(u) = u³, so f'(u) = 3u²

Step 2: Apply chain rule

h'(x) = f'(g(x)) × g'(x)

= 3(x² + 1)² × 2x

= 6x(x² + 1)²

Why Chain Rule Matters for ML

Neural networks are compositions of functions!

Output = f₄(f₃(f₂(f₁(Input))))

Each layer is a function applied to the previous layer’s output. To compute gradients (how output changes with respect to inputs), we need the chain rule.

Backpropagation—the algorithm that trains neural networks—is essentially the chain rule applied repeatedly through the network’s layers.

Intuitive Understanding

Think of a chain of causes:

Input → Layer 1 → Layer 2 → Layer 3 → Output → Loss

To find how Input affects Loss, we multiply:

- How Input affects Layer 1

- How Layer 1 affects Layer 2

- How Layer 2 affects Layer 3

- How Layer 3 affects Output

- How Output affects Loss

Each “how X affects Y” is a derivative. Multiplying them together is the chain rule!

Partial Derivatives: Multiple Variables

Real machine learning models have thousands or millions of parameters. We need to understand how each parameter individually affects the loss.

What Are Partial Derivatives?

For a function of multiple variables f(x, y, z), a partial derivative measures how f changes with respect to one variable while holding others constant.

Notation:

- ∂f/∂x: Partial derivative with respect to x (treat y and z as constants)

- ∂f/∂y: Partial derivative with respect to y (treat x and z as constants)

- ∂f/∂z: Partial derivative with respect to z (treat x and y as constants)

Computing Partial Derivatives

To find ∂f/∂x, treat all other variables as constants and take the derivative with respect to x.

Example: f(x, y) = x²y + 3xy²

∂f/∂x (treat y as constant):

∂f/∂x = 2xy + 3y²

∂f/∂y (treat x as constant):

∂f/∂y = x² + 6xy

In Machine Learning

A neural network might have parameters w₁, w₂, …, wₙ and loss function L(w₁, w₂, …, wₙ).

We need:

- ∂L/∂w₁: How loss changes with w₁

- ∂L/∂w₂: How loss changes with w₂

- … and so on for all parameters

Each partial derivative tells us how to adjust one specific parameter to reduce loss.

Example: Linear Regression

For linear regression y = w₁x + w₂ (where w₁ is slope, w₂ is intercept), with loss function:

L = (y_predicted - y_actual)² = (w₁x + w₂ - y_actual)²

Partial derivatives:

∂L/∂w₁ = 2(w₁x + w₂ - y_actual) × x

∂L/∂w₂ = 2(w₁x + w₂ - y_actual) × 1

These tell us how to adjust w₁ and w₂ to reduce loss!

The Gradient: Vector of Partial Derivatives

When you have a function of multiple variables, the gradient combines all partial derivatives into a single vector.

Gradient Definition

For function f(x, y, z), the gradient is:

∇f = [∂f/∂x, ∂f/∂y, ∂f/∂z]

The gradient is a vector pointing in the direction of steepest increase.

Example

For f(x, y) = x² + xy + y²:

∂f/∂x = 2x + y

∂f/∂y = x + 2y

∇f = [2x + y, x + 2y]

At point (1, 2):

∇f = [2(1) + 2, 1 + 2(2)] = [4, 5]

This vector [4, 5] points in the direction where f increases most rapidly.

Gradient Descent

Since the gradient points uphill (toward increasing values), the negative gradient points downhill (toward decreasing values).

To minimize a function, move in the direction opposite to the gradient:

x_new = x_old - learning_rate × ∇f(x_old)

This is gradient descent—the fundamental optimization algorithm in machine learning!

Gradient in Machine Learning

For a model with parameters w = [w₁, w₂, …, wₙ] and loss function L(w):

∇L = [∂L/∂w₁, ∂L/∂w₂, ..., ∂L/∂wₙ]

Update rule:

w_new = w_old - learning_rate × ∇L

Each parameter is adjusted based on its partial derivative—how much it affects the loss.

Gradient Descent: Putting It All Together

Gradient descent is where calculus concepts come together to enable machine learning.

The Algorithm

1. Initialize parameters randomly

2. Repeat until convergence:

a. Compute predictions using current parameters

b. Calculate loss (error)

c. Compute gradient (partial derivatives of loss)

d. Update parameters: w = w - learning_rate × gradient

Steps 2c and 2d use calculus!

Visual Intuition

Imagine standing on a hillside in fog—you can’t see the overall terrain but can feel which direction slopes downward.

- Your position: Current parameters

- Elevation: Loss value

- Goal: Reach the valley (minimum loss)

- Strategy: Feel the slope (gradient), take a step downhill

- Repeat: Keep stepping downhill until you reach the bottom

The gradient tells you which direction is downhill. The learning rate determines step size.

Learning Rate: How Big a Step?

w_new = w_old - learning_rate × gradient

Learning rate too large:

- Take huge steps

- Might overshoot minimum

- Could bounce around or diverge

Learning rate too small:

- Take tiny steps

- Very slow convergence

- Might get stuck in local minimum

Choosing the right learning rate is crucial (often 0.001, 0.01, or 0.1).

Example: Simple Function

Minimize f(x) = (x – 3)²

Derivative: f'(x) = 2(x – 3)

Starting point: x = 0 Learning rate: 0.1

Iteration 1:

gradient = f'(0) = 2(0 - 3) = -6

x_new = 0 - 0.1 × (-6) = 0.6

Iteration 2:

gradient = f'(0.6) = 2(0.6 - 3) = -4.8

x_new = 0.6 - 0.1 × (-4.8) = 1.08

Continue…

After many iterations, x approaches 3 (the minimum of f(x) = (x-3)²).

Stochastic Gradient Descent

Real datasets have millions of examples. Computing the gradient using all data is slow.

Solution: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

- Use a random subset (mini-batch) of data

- Compute approximate gradient

- Update parameters

- Repeat with different mini-batches

The gradient is noisier but updates are much faster. This enables training on large datasets.

Backpropagation: Chain Rule in Action

Backpropagation is how neural networks compute gradients. It’s the chain rule applied systematically through the network.

The Challenge

A neural network with layers:

Input → Layer1 → Layer2 → Layer3 → Output → Loss

We need:

- ∂Loss/∂(Layer3 weights)

- ∂Loss/∂(Layer2 weights)

- ∂Loss/∂(Layer1 weights)

Each layer’s gradient depends on later layers—we need the chain rule!

Forward Pass

Compute predictions layer by layer:

h1 = f1(Input × W1 + b1)

h2 = f2(h1 × W2 + b2)

h3 = f3(h2 × W3 + b3)

output = f4(h3 × W4 + b4)

loss = L(output, target)

Backward Pass

Compute gradients layer by layer, working backward:

∂loss/∂output (direct calculation)

∂loss/∂h3 = ∂loss/∂output × ∂output/∂h3 (chain rule)

∂loss/∂h2 = ∂loss/∂h3 × ∂h3/∂h2 (chain rule)

∂loss/∂h1 = ∂loss/∂h2 × ∂h2/∂h1 (chain rule)

Then for each layer’s weights:

∂loss/∂W4 = ∂loss/∂output × ∂output/∂W4

∂loss/∂W3 = ∂loss/∂h3 × ∂h3/∂W3

∂loss/∂W2 = ∂loss/∂h2 × ∂h2/∂W2

∂loss/∂W1 = ∂loss/∂h1 × ∂h1/∂W1

Each gradient calculation uses the chain rule!

Why “Back”propagation?

Gradients propagate backward through the network:

- Start at the loss (output end)

- Compute gradients layer by layer moving backward

- Reach the input end with all gradients computed

The name describes the computational flow direction.

Computational Efficiency

Computing gradients backward is efficient because:

- Forward pass already computed all intermediate values

- Each gradient uses previously computed gradients

- One backward pass computes all parameter gradients

Without this efficient algorithm, training deep networks would be impractical.

Activation Functions and Their Derivatives

Neural networks use activation functions to introduce non-linearity. Understanding their derivatives is important.

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit)

Function:

f(x) = max(0, x) = {x if x > 0, 0 if x ≤ 0}

Derivative:

f'(x) = {1 if x > 0, 0 if x ≤ 0}

Why it matters: ReLU is popular because:

- Simple derivative (0 or 1)

- Computationally efficient

- Helps avoid vanishing gradient problem

Sigmoid

Function:

f(x) = 1 / (1 + e^(-x))

Derivative:

f'(x) = f(x) × (1 - f(x))

Why it matters:

- Used in binary classification

- Derivative is simple to compute from function value

- Can cause vanishing gradients (derivative approaches 0 for large |x|)

Tanh (Hyperbolic Tangent)

Function:

f(x) = (e^x - e^(-x)) / (e^x + e^(-x))

Derivative:

f'(x) = 1 - f(x)²

Why it matters:

- Zero-centered (outputs between -1 and 1)

- Derivative computed easily from function value

- Still can have vanishing gradient issues

Softmax

Used for multi-class classification. More complex derivative involving Jacobian matrix.

Why it matters: Converts network outputs to probabilities that sum to 1.

Loss Functions and Their Derivatives

The loss function measures model error. Its derivative guides learning.

Mean Squared Error (MSE)

Function (for one example):

L = (y_predicted - y_actual)²

Derivative:

∂L/∂y_predicted = 2(y_predicted - y_actual)

Use: Regression problems

Binary Cross-Entropy

Function:

L = -[y × log(p) + (1-y) × log(1-p)]

Where y is actual (0 or 1), p is predicted probability.

Derivative:

∂L/∂p = -(y/p) + (1-y)/(1-p)

Use: Binary classification

Categorical Cross-Entropy

For multi-class classification with C classes:

Function:

L = -Σ y_c × log(p_c)

Where y_c is 1 for correct class, 0 for others.

Derivative: Different for each class based on whether it’s the true class.

Use: Multi-class classification

Common Issues and Their Calculus Explanations

Understanding calculus helps diagnose training problems.

Vanishing Gradients

Problem: Gradients become extremely small in early layers of deep networks.

Calculus explanation:

- Chain rule multiplies many derivatives

- If derivatives are less than 1, repeated multiplication makes them tiny

- With sigmoid activation: derivative is at most 0.25

- Through 10 layers: 0.25^10 ≈ 0.000001 (essentially zero!)

Solution: Use ReLU (derivative is 1 for positive values) or other techniques.

Exploding Gradients

Problem: Gradients become extremely large.

Calculus explanation:

- Chain rule multiplies derivatives

- If derivatives are greater than 1, repeated multiplication makes them huge

- Can cause weight updates that overshoot dramatically

Solution: Gradient clipping (limit maximum gradient magnitude) or careful initialization.

Local Minima

Problem: Gradient descent converges to local minimum, not global minimum.

Calculus explanation:

- Gradient is zero at local minima (and maxima and saddle points)

- Gradient descent stops when gradient reaches zero

- No information about whether this is the best possible minimum

Solution: Multiple random initializations, momentum methods, or better optimization algorithms.

Saddle Points

Problem: Point where gradient is zero but it’s neither maximum nor minimum (like a mountain pass).

Calculus explanation:

- First derivative is zero

- Second derivatives show it’s a saddle (increasing in some directions, decreasing in others)

- In high dimensions, saddle points are more common than local minima

Solution: Momentum-based optimizers help escape saddle points.

Practical Calculus Tools

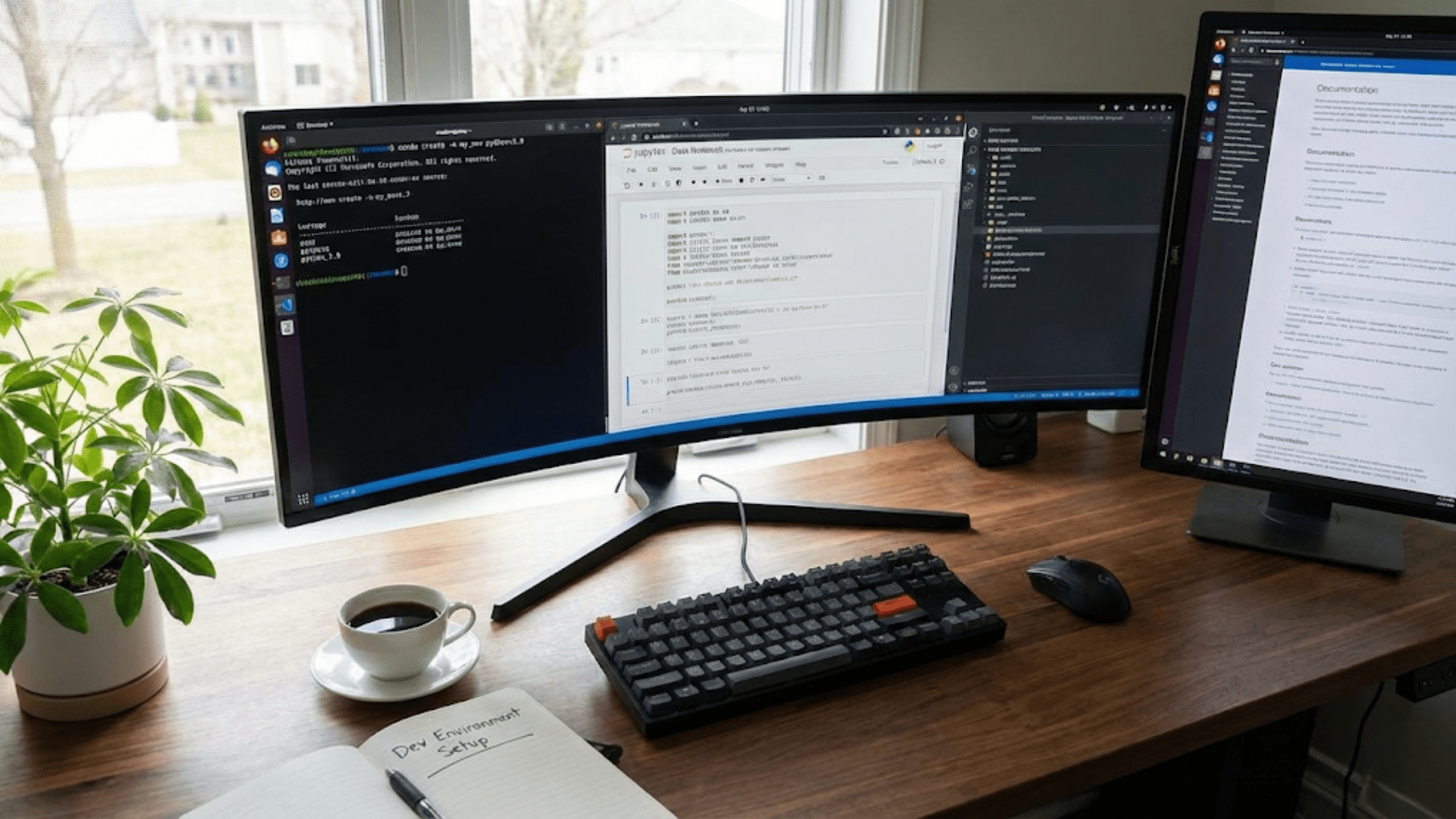

You rarely compute derivatives manually. Libraries handle this through automatic differentiation.

Automatic Differentiation

Modern frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch) automatically compute gradients:

import torch

# Define variables that require gradients

x = torch.tensor(2.0, requires_grad=True)

y = torch.tensor(3.0, requires_grad=True)

# Compute function

z = x**2 + 2*x*y + y**2

# Compute gradients automatically!

z.backward()

print(x.grad) # ∂z/∂x at x=2, y=3

print(y.grad) # ∂z/∂y at x=2, y=3The framework tracks all operations and applies the chain rule automatically.

How Automatic Differentiation Works

- Forward pass: Compute function value, track operations

- Backward pass: Apply chain rule systematically to compute gradients

- Store gradients: Make them accessible for optimization

This is called “reverse-mode automatic differentiation” and is exactly what backpropagation does.

Symbolic vs Numerical vs Automatic Differentiation

Symbolic: Manipulate mathematical expressions (like doing calculus by hand)

- Exact but can be complex

Numerical: Approximate using finite differences

- f'(x) ≈ [f(x + h) – f(x)] / h

- Simple but imprecise and slow

Automatic: Track operations and apply chain rule computationally

- Exact (within floating-point precision)

- Efficient

- Used by all modern deep learning frameworks

What You Actually Need to Know

Let’s be honest about what calculus knowledge is practically necessary:

Essential Understanding

Must know:

- What a derivative represents (rate of change)

- Gradient points toward increasing values

- Negative gradient points toward decreasing values

- Chain rule connects derivatives through compositions

- Partial derivatives measure change in one variable

Should understand conceptually:

- How gradient descent uses derivatives to optimize

- Why backpropagation needs the chain rule

- How loss function derivatives guide learning

- What gradients tell us about model training

Not Essential for Practice

Don’t need to:

- Compute complex derivatives by hand

- Memorize derivative formulas

- Derive backpropagation equations yourself

- Perform calculus proofs

- Understand measure theory or advanced analysis

Libraries handle:

- All derivative computations

- Gradient calculations

- Backpropagation implementation

- Optimization algorithms

When Deep Understanding Helps

Advanced understanding is valuable when:

- Designing new activation functions

- Creating novel architectures

- Debugging unusual training issues

- Doing AI research

- Optimizing performance

But for applying existing techniques and understanding how models work, conceptual understanding suffices.

Connecting Calculus to ML Workflow

Let’s see how calculus fits into the actual machine learning workflow:

Data Preparation

Calculus role: None directly—working with data structures and cleaning.

Model Definition

Calculus role: Minimal—defining architecture and activation functions.

Forward Pass (Prediction)

Calculus role: None directly—just computing function outputs.

Loss Calculation

Calculus role: Evaluating the loss function.

Backward Pass (Computing Gradients)

Calculus role: Critical! This is where derivatives are computed.

- Chain rule through network layers

- Partial derivatives for each parameter

- Automatic differentiation does the work

Parameter Update

Calculus role: Critical! Gradient descent uses gradients.

parameters -= learning_rate × gradients

Repeat Training

Calculus role: Every iteration uses gradient computation and update.

Conclusion: Calculus enables the learning in machine learning!

Building Intuition: The Optimization Perspective

Thinking about calculus through the lens of optimization helps intuition:

The Landscape Metaphor

Imagine the loss function as a landscape:

- Height: Loss value (lower is better)

- Position: Parameter values

- Goal: Find the lowest valley

Derivative/gradient: Tells you the slope at your current position Gradient descent: Strategy of always walking downhill Learning rate: How big your steps are Local minimum: A valley you might get stuck in Global minimum: The deepest valley (best possible parameters)

This metaphor makes calculus concepts concrete and intuitive.

Multiple Parameters

With many parameters, the landscape is high-dimensional (can’t visualize), but the principles remain:

- Gradient is a vector pointing uphill in all dimensions

- Move opposite to gradient to go downhill

- Eventually reach a minimum (hopefully global, often local)

Conclusion: Calculus as a Tool for Learning

Calculus provides the mathematical foundation that makes machine learning possible. Specifically:

Derivatives measure how model parameters affect error, telling us which direction to adjust parameters.

The chain rule enables backpropagation, computing gradients efficiently through deep networks.

Gradients combine partial derivatives, providing a complete picture of how all parameters affect loss.

Gradient descent uses gradients to iteratively improve parameters, enabling model training.

Without calculus, we couldn’t:

- Train neural networks through backpropagation

- Know which direction improves model performance

- Understand why learning works

- Debug training issues

- Optimize hyperparameters effectively

But here’s the good news: you don’t need to be a calculus expert to work effectively with machine learning. You need conceptual understanding of what derivatives mean, how gradients guide optimization, and why the chain rule matters. The actual computation happens automatically in modern frameworks.

Understanding these concepts transforms machine learning from mysterious black magic into a logical process: define a model, measure its error, compute how parameters affect error (calculus!), adjust parameters to reduce error, and repeat. The “magic” of learning is just calculus applied systematically.

Every time a neural network improves during training, calculus is working behind the scenes. Every parameter update is guided by derivatives. Every step toward better predictions follows the gradient. Calculus is the invisible hand that guides machine learning models from random initialization to accurate prediction.

You now understand the mathematical principle that makes artificial intelligence learn. This knowledge doesn’t just help you use ML tools—it helps you understand why they work, when they’ll succeed, and how to improve them. That’s the true power of understanding the calculus foundations of artificial intelligence.