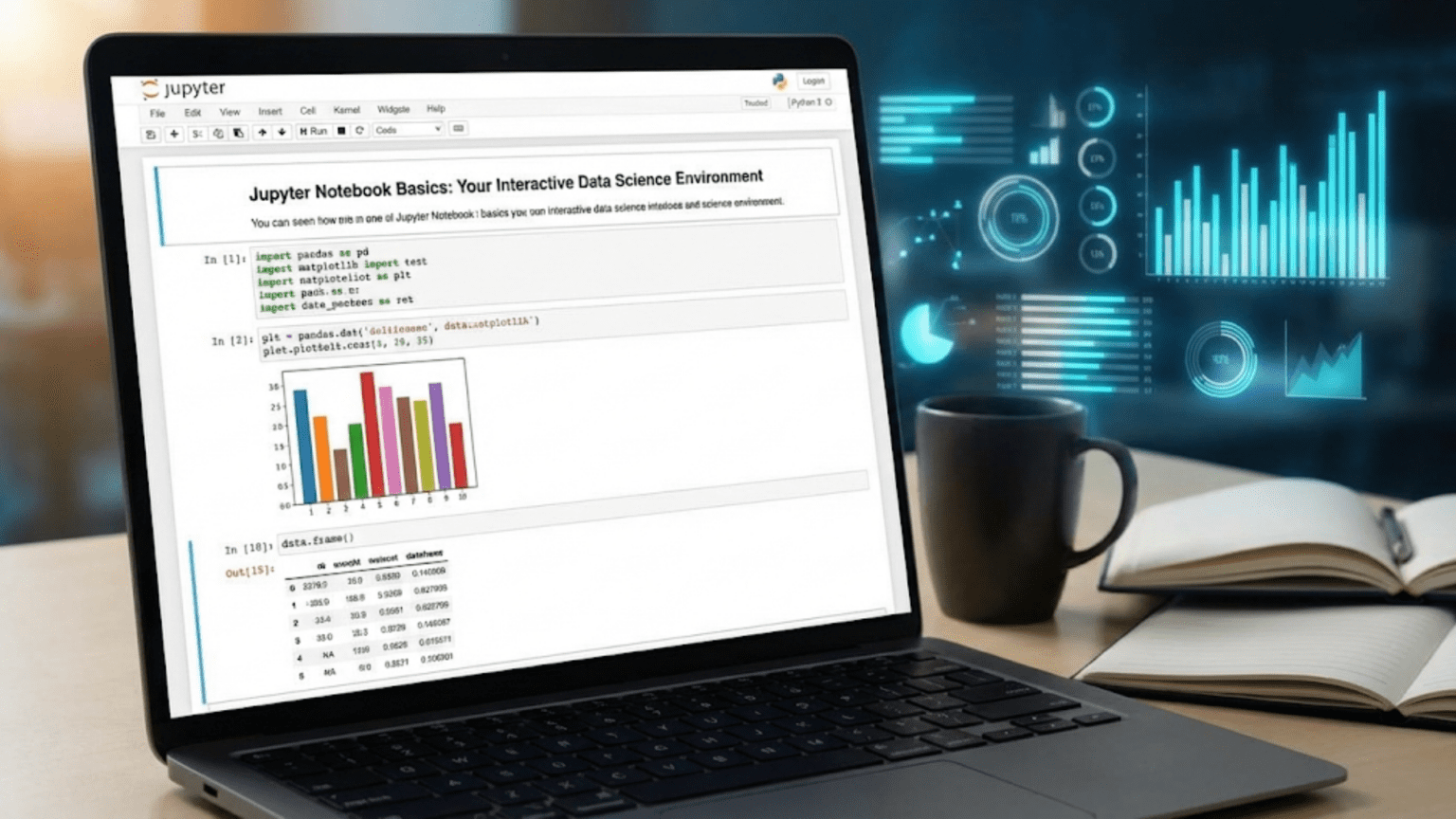

Jupyter Notebook is a free, open-source web application that lets you create and share documents combining live Python code, visualizations, equations, and narrative text — all in a single interactive environment running in your browser. It is the most widely used tool for exploratory data analysis, machine learning experimentation, and data science education worldwide.

Introduction: Why Jupyter Notebook Changed Data Science

Before Jupyter Notebook, data scientists typically wrote Python scripts in text editors, ran them from the command line, and viewed outputs in a terminal window. This workflow worked, but it had a fundamental limitation: you could not easily see intermediate results, explore data interactively, or combine code with explanations in a human-readable document.

Jupyter Notebook solved all of this. It introduced a radically different paradigm — the computational notebook — where code, output, visualizations, and prose documentation live together in a single interactive document that runs in your web browser. You write a few lines of code, press Shift+Enter, and see the result immediately below. You adjust the code, run it again, and observe the change. You add a paragraph of text explaining your findings. You embed a chart that updates every time the data changes.

This interactive, iterative workflow transformed how data science is done. Today, Jupyter Notebook is used by millions of data scientists, researchers, educators, and analysts worldwide. It is the standard environment for sharing data science work, the default interface for many online platforms (including Google Colab and Kaggle), and the foundation on which data science education is built.

If you are beginning your data science journey, mastering Jupyter Notebook is not optional — it is essential. This article will take you from installation through every fundamental concept you need to work productively in Jupyter, with practical guidance rooted in real data science workflows.

1. What Is Jupyter Notebook?

1.1 The Origin and Name

Jupyter Notebook was created by Fernando Pérez and Brian Granger, growing out of the IPython project. The name “Jupyter” is a combination of the three core programming languages it originally supported: Julia, Python, and R. Today, Jupyter supports over 40 programming languages through a kernel system, though Python remains by far the most common.

The project is maintained by Project Jupyter, a non-profit open-source organization. Jupyter Notebook is entirely free to use and is available on every major operating system.

1.2 How It Works Technically

Understanding how Jupyter works under the hood helps you avoid confusion and troubleshoot problems:

The Notebook File (.ipynb): A Jupyter notebook is saved as a .ipynb file (IPython Notebook). This file is actually a JSON document that stores all your cells — both their content (code or text) and their outputs (results, error messages, images). When you share a .ipynb file, you share not just code but the entire interactive document including its outputs.

The Kernel: Behind every running notebook is a kernel — a separate process that executes your code. When you run a Python cell, the notebook sends that code to the Python kernel, which executes it and sends the result back to the browser for display. The kernel maintains state between cell executions, which means variables defined in one cell are available in subsequent cells.

The Server: Jupyter runs a local web server on your computer (typically at http://localhost:8888). Your browser connects to this server to display the notebook interface. This is why Jupyter opens in a browser even though everything runs locally on your machine.

Your Browser ←→ Jupyter Server (localhost:8888) ←→ Python Kernel

[displays] [manages files] [executes code]1.3 Jupyter Notebook vs JupyterLab

You may hear both “Jupyter Notebook” and “JupyterLab” mentioned. Here is the key distinction:

Jupyter Notebook (Classic): The original interface — simpler, focused on a single notebook at a time, with a clean and minimal UI. Great for beginners and for straightforward analysis work.

JupyterLab: A more powerful, IDE-like interface that can display multiple notebooks, terminal windows, file browsers, and text editors simultaneously in a tabbed layout. JupyterLab is the next-generation interface and is now the default in many installations.

Both use the same .ipynb file format and the same kernel system. This article focuses on the classic Jupyter Notebook interface because it is more beginner-friendly, but almost everything you learn here applies equally to JupyterLab.

2. Installing Jupyter Notebook

2.1 The Recommended Approach: Anaconda

The easiest way to install Jupyter Notebook is through Anaconda, a Python distribution that bundles Jupyter, Python, and hundreds of data science libraries in a single installer. If you followed the earlier article on setting up your data science environment, you likely already have Jupyter installed.

To verify:

# Open your terminal (Mac/Linux) or Anaconda Prompt (Windows)

jupyter notebook --version

# If installed, you'll see something like:

# 7.1.0If Jupyter is not installed, install it via Anaconda:

# Using conda (recommended if you have Anaconda)

conda install jupyter

# Or using pip (if you have Python installed without Anaconda)

pip install notebook2.2 Installing in a Virtual Environment

Best practice is to install Jupyter in a dedicated virtual environment for your project:

# Create a new conda environment with Python and Jupyter

conda create -n datascience python=3.11 jupyter pandas numpy matplotlib seaborn scikit-learn

# Activate the environment

conda activate datascience

# Launch Jupyter from within the environment

jupyter notebookUsing environments ensures your project dependencies do not conflict with each other and makes your work reproducible.

2.3 Launching Jupyter Notebook

Once installed, launching Jupyter is simple:

# Navigate to your project directory first (important!)

cd /path/to/your/project

# Launch Jupyter Notebook

jupyter notebookThis opens your default web browser and displays the Jupyter Dashboard — a file browser showing the contents of the directory you launched from. From here you can open existing notebooks or create new ones.

Important: Always navigate to your project directory before launching Jupyter. The directory you launch from becomes the root of Jupyter’s file browser. You can only access files within that directory tree from the Jupyter interface.

3. The Jupyter Interface: A Complete Tour

3.1 The Dashboard

When Jupyter first opens, you see the Dashboard — a file browser with three tabs:

- Files: Browse and open files and folders. Create new notebooks here.

- Running: See which notebooks and terminals are currently running (and shut them down if needed).

- Clusters: For parallel computing (advanced; ignore for now).

To create a new notebook, click the “New” button in the top right corner and select “Python 3” (or your installed kernel). This opens a new, empty notebook.

3.2 The Notebook Interface

A Jupyter notebook consists of several key UI elements:

Menu Bar: At the top — File, Edit, View, Insert, Cell, Kernel, Widgets, Help. Most operations you need are accessible here.

Toolbar: Below the menu bar — buttons for common actions like saving, adding cells, running cells, and stopping the kernel.

Kernel Indicator: In the top right corner, shows the current kernel (e.g., “Python 3”) and a circle that is filled (●) when the kernel is busy executing code and empty (○) when idle.

Cell Area: The main body of the notebook — where you write code and text.

Status Bar: At the bottom — shows the current cell mode and other status information.

3.3 Understanding Cells

The fundamental unit of a Jupyter notebook is the cell. Every piece of content — code, text, equations — lives in a cell. There are three cell types:

Code Cells: Contain Python code (or whatever language your kernel runs). When executed, output appears directly below the cell. Code cells have In [n]: labels on the left where n is the execution order number.

Markdown Cells: Contain formatted text written in Markdown syntax. When executed (rendered), they display as formatted prose with headings, bold text, lists, links, images, and more.

Raw Cells: Contain unformatted text that is passed directly to the output without any execution or rendering. Rarely used by beginners.

4. Working with Code Cells

4.1 Running Your First Code Cell

Click inside a cell (it gets a blue or green border) and type some Python code:

# Your first Jupyter code cell

print("Hello, Jupyter!")

2 + 2Run the cell by pressing Shift+Enter. Three things happen:

- The code executes in the kernel

- The output appears immediately below the cell

- The cursor moves to the next cell (or creates a new one if you were in the last cell)

The output shows:

Hello, Jupyter!

4Notice that print() statements display their output, and the last expression in a cell is automatically displayed without needing print(). This is a key feature of Jupyter — the last evaluated expression becomes the cell’s output.

4.2 Cell Execution Numbers

The In [n]: label on the left of each code cell shows the execution order:

In [1]: # First cell you ran

In [2]: # Second cell you ran

In [*]: # Currently running (asterisk means in progress)These numbers are crucial for understanding the execution state of your notebook. The kernel maintains all variables in memory from all previously executed cells, regardless of their visual position in the notebook. If you run cell 5 before cell 3, cell 3’s code may depend on variables defined in cell 5.

4.3 The Kernel State: Why Order Matters

This is the most important conceptual point about Jupyter for beginners: the kernel remembers all variables from all previously run cells, but it does not care about their position in the notebook — only about the order in which they were executed.

# Cell 1 (run first)

x = 10

# Cell 2 (run second)

y = x + 5

print(y) # 15 ✓

# Now if you delete Cell 1 and run Cell 2 again...

# NameError: name 'x' is not defined

# Because x only existed from Cell 1's executionThis creates a common beginner trap: a notebook that appears to work (because you ran everything in order) but fails when someone else tries to run it top-to-bottom, because you had deleted or modified earlier cells after running them.

Best practice: Periodically restart your kernel and run all cells from top to bottom (Kernel → Restart & Run All) to verify your notebook works as a coherent document.

4.4 Displaying Rich Output

Jupyter notebooks render rich output types automatically:

# DataFrames display as formatted HTML tables

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1,2,3], 'B': [4,5,6]})

df # Just type the variable name — Jupyter renders it as a table# Matplotlib charts display inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 100)

plt.plot(x, np.sin(x), label='sin(x)')

plt.plot(x, np.cos(x), label='cos(x)')

plt.legend()

plt.title('Trigonometric Functions')

plt.show()

# The chart appears directly below the cell# Configure matplotlib for inline display (add to first cell)

%matplotlib inline

# Now all plots appear in the notebook automatically5. Markdown Cells: Adding Text and Documentation

5.1 Changing a Cell to Markdown

To change a code cell to a Markdown cell:

- Press M while the cell is selected (in Command Mode — see Section 6)

- Or use the dropdown in the toolbar (change “Code” to “Markdown”)

- Or go to Cell → Cell Type → Markdown

5.2 Markdown Syntax Essentials

Markdown is a lightweight text formatting language that converts plain text into HTML. Here are the most important Markdown elements for data science notebooks:

Headings:

# Heading 1 (largest)

## Heading 2

### Heading 3

#### Heading 4Text Formatting:

**Bold text**

*Italic text*

`inline code`

~~Strikethrough~~Lists:

Unordered list:

- Item one

- Item two

- Nested item

Ordered list:

1. First step

2. Second step

3. Third stepLinks and Images:

[Link text](https://example.com)

Code Blocks:

```python

def hello():

print("Hello, World!")

```Mathematical Equations (LaTeX):

Inline math: $y = mx + b$

Display math (centered):

$$\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i$$Tables:

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 |

|----------|----------|----------|

| Value A | Value B | Value C |

| Value D | Value E | Value F |5.3 Structuring a Professional Notebook with Markdown

A well-structured data science notebook uses Markdown to create a logical narrative flow. Here is a recommended structure:

# Project Title

## 1. Introduction

Brief description of the problem, goals, and dataset.

## 2. Setup and Imports

```python

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

## 3. Data Loading and Exploration

### 3.1 Load Data

### 3.2 Initial Inspection

## 4. Data Cleaning

## 5. Exploratory Data Analysis

## 6. Modeling

## 7. Results and ConclusionsThis narrative structure transforms a collection of code snippets into a readable, publishable document — exactly what prospective employers and collaborators expect to see in a data science portfolio.

6. Keyboard Shortcuts: The Key to Productivity

Jupyter has two modes with different keyboard behaviors, and understanding them is fundamental to working efficiently.

6.1 Command Mode vs Edit Mode

Edit Mode (green cell border): You are typing inside a cell. Normal typing behavior applies.

Command Mode (blue cell border): You are navigating between cells. Keyboard shortcuts for notebook-level operations are active.

Switch between modes:

- Enter: Command Mode → Edit Mode (start editing the selected cell)

- Escape: Edit Mode → Command Mode (stop editing, keep cell selected)

6.2 Essential Keyboard Shortcuts

Running Cells:

| Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

Shift + Enter | Run cell, move to next cell (most common) |

Ctrl + Enter | Run cell, stay on current cell |

Alt + Enter | Run cell, insert new cell below |

Navigation (Command Mode):

| Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

↑ / ↓ or K / J | Move to previous / next cell |

A | Insert cell Above current cell |

B | Insert cell Below current cell |

D, D (press D twice) | Delete selected cell |

Z | Undo cell deletion |

M | Change cell to Markdown |

Y | Change cell to Code |

L | Toggle line numbers |

O | Toggle output display |

H | Show keyboard shortcut help |

Selection and Editing (Command Mode):

| Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

Shift + ↑ / Shift + ↓ | Select multiple cells |

Shift + M | Merge selected cells |

X | Cut selected cell(s) |

C | Copy selected cell(s) |

V | Paste cell(s) below |

Shift + V | Paste cell(s) above |

Kernel Operations (Command Mode):

| Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

I, I (press I twice) | Interrupt kernel (stop running code) |

0, 0 (press 0 twice) | Restart kernel |

In Edit Mode:

| Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

Tab | Code completion / indent |

Shift + Tab | Show function signature / docstring |

Ctrl + / | Toggle comment |

Ctrl + Z | Undo |

Ctrl + Shift + - | Split cell at cursor |

Tip: Press H in Command Mode to open the full shortcut reference. Investing 30 minutes to learn the core shortcuts will pay back many hours over your career.

7. Working with the Kernel

7.1 Restarting the Kernel

The kernel can be in various states, and knowing how to manage it is important:

Interrupt the Kernel (stop running code): Use I, I in Command Mode or click the ■ button in the toolbar. Use this when code is taking too long or caught in an infinite loop.

Restart the Kernel: Kernel → Restart. This clears all variables from memory but does not clear cell outputs. Cell execution numbers reset.

Restart and Clear Output: Kernel → Restart & Clear Output. Clears all outputs and resets the kernel — gives you a completely fresh state.

Restart and Run All: Kernel → Restart & Run All. The most important operation for verifying your notebook works correctly from top to bottom. Always do this before sharing a notebook.

7.2 Checking What’s in Memory

To see all variables currently in the kernel’s memory:

# List all variables in the current namespace

%who

# List variables with their types and sizes

%whosVariable Type Data/Info

--------------------------------

df DataFrame 5 rows x 3 cols

x int 10

y float 15.57.3 The Danger of Hidden State

One of the most common Jupyter pitfalls is hidden kernel state — variables that exist in memory from cells you ran earlier but that are no longer visible in the current notebook state (because you deleted or modified those cells).

Example scenario that causes problems:

- You define

data = load_large_dataset()in Cell 3 - You run many subsequent cells that use

data - You delete Cell 3 (thinking you no longer need that code)

- Everything still works because

datais still in memory - You restart the kernel, try to run the notebook again

- Cell 4 crashes:

NameError: name 'data' is not defined

The solution is simple: Restart & Run All periodically, especially before sharing your notebook.

8. Saving, Exporting, and Sharing Notebooks

8.1 Saving Your Work

Jupyter auto-saves your notebook periodically (usually every 2 minutes), but you should also save manually with Ctrl+S (or Cmd+S on Mac). You can see the last save time displayed next to the notebook title at the top.

Checkpoints: Jupyter automatically creates checkpoints (snapshots) of your notebook. You can revert to the last checkpoint via File → Revert to Checkpoint. This is useful if you accidentally delete important cells.

8.2 Exporting Notebooks

Jupyter can export notebooks to many formats via File → Download as:

- .ipynb: The notebook file itself (for sharing with other Jupyter users)

- .html: An HTML version — the output renders in any browser without Jupyter installed

- .pdf: A PDF document (requires LaTeX to be installed)

- .py: A Python script — strips all Markdown and outputs, keeps only code

- .md: Markdown format

For sharing with non-technical stakeholders who cannot run Jupyter themselves, HTML export is the most practical option — it preserves all outputs including charts and is viewable in any browser.

8.3 Sharing via GitHub and nbviewer

Jupyter notebooks stored on GitHub are automatically rendered as static HTML when viewed in a browser — you can see all the outputs without running any code. This makes GitHub an ideal platform for sharing data science notebooks.

For a richer rendering experience, use nbviewer (nbviewer.org): paste a GitHub URL to a .ipynb file and nbviewer renders it as a clean, full-featured HTML page. Many data science teams and researchers share their work this way.

9. Essential Jupyter Features for Data Science

9.1 Tab Completion

Jupyter provides intelligent code completion. Inside a code cell, type the beginning of a variable name, function name, or method and press Tab:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1,2,3]})

df. # Press Tab after the dot to see all DataFrame methods

df.gr # Press Tab to complete to df.groupby, df.drop, etc.Tab completion works for:

- Variable names in scope

- Module names and their attributes

- Function parameters

- File paths (when writing strings)

9.2 Function Documentation with Shift+Tab

While your cursor is inside a function call, press Shift+Tab to show the function’s signature and docstring:

pd.read_csv( # Press Shift+Tab here to see all parametersPress Shift+Tab multiple times to expand the documentation to full size. This is an invaluable feature — you can explore any function’s parameters without leaving the notebook.

9.3 Displaying Help

# Show full documentation for any function or object

help(pd.DataFrame.groupby)

# Alternative syntax (displays in a pane below)

pd.DataFrame.groupby?

# Show source code

pd.DataFrame.groupby??9.4 Running Shell Commands

You can run shell commands directly in a code cell by prefixing them with !:

# Install a package

!pip install seaborn

# List files in the current directory

!ls -la

# Check which Python is being used

!which python

# Create a directory

!mkdir data

# Download a file

!wget https://example.com/dataset.csv -O data/dataset.csvThis is extremely useful for environment setup steps that you want documented alongside your code.

9.5 Timing Code Execution

Jupyter provides convenient timing utilities:

# Time a single line of code

%timeit [x**2 for x in range(1000)]

# 126 µs ± 2.37 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10,000 loops each)

# Time an entire cell

%%timeit

import numpy as np

arr = np.arange(1000)

result = arr ** 2

# Time and display wall clock time

import time

start = time.time()

# ... your code ...

print(f"Elapsed: {time.time() - start:.3f}s")10. A Complete Data Science Workflow in Jupyter

Let us walk through a realistic, structured data science notebook from start to finish:

# Cell 1: Setup (Markdown)Sales Data Analysis

Objective

Analyze Q1 2026 sales data to identify top-performing products and regions. Author: Data Science Team | Date: 2026-01-01

# Cell 2: Imports and Configuration

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

%matplotlib inline

plt.style.use('seaborn-v0_8-whitegrid')

pd.set_option('display.max_columns', 20)

pd.set_option('display.float_format', '{:.2f}'.format)

print("Libraries loaded successfully ✓")

print(f"Pandas version: {pd.__version__}")

print(f"NumPy version: {np.__version__}")# Cell 3: Data Generation (simulating loading from CSV)

np.random.seed(42)

n = 300

sales = pd.DataFrame({

'date': pd.date_range('2024-01-01', periods=n, freq='D')[:n],

'product': np.random.choice(['Laptop', 'Mouse', 'Monitor', 'Keyboard', 'Webcam'], n),

'region': np.random.choice(['North', 'South', 'East', 'West'], n),

'units': np.random.randint(1, 20, n),

'unit_price':np.random.choice([999.99, 29.99, 349.99, 79.99, 89.99], n)

})

sales['revenue'] = sales['units'] * sales['unit_price']

print(f"Dataset shape: {sales.shape}")

sales.head()# Cell 4: Data Inspection (Markdown)Data Overview

We have {n} daily sales records covering Q1 2026 across 5 products and 4 regions.

# Cell 5: Exploratory Statistics

print("=== Basic Statistics ===")

print(sales.describe().round(2))

print(f"\nDate range: {sales['date'].min().date()} → {sales['date'].max().date()}")

print(f"Total revenue: ${sales['revenue'].sum():,.2f}")

print(f"Unique products: {sales['product'].nunique()}")# Cell 6: Revenue by Product

product_revenue = sales.groupby('product')['revenue'].sum().sort_values(ascending=False)

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5))

# Bar chart

product_revenue.plot(kind='bar', ax=ax1, color='steelblue', edgecolor='white')

ax1.set_title('Total Revenue by Product', fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

ax1.set_xlabel('Product')

ax1.set_ylabel('Revenue ($)')

ax1.set_xticklabels(ax1.get_xticklabels(), rotation=45, ha='right')

ax1.yaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: f'${x:,.0f}'))

# Pie chart

ax2.pie(product_revenue, labels=product_revenue.index, autopct='%1.1f%%',

colors=sns.color_palette('Set2'))

ax2.set_title('Revenue Share by Product', fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('product_revenue.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

print("\nTop product:", product_revenue.index[0])

print(f"Revenue: ${product_revenue.iloc[0]:,.2f}")# Cell 7: Regional Analysis

region_summary = sales.groupby('region').agg(

total_revenue=('revenue', 'sum'),

avg_order=('revenue', 'mean'),

transactions=('revenue', 'count')

).round(2)

region_summary['revenue_share_%'] = (

region_summary['total_revenue'] / region_summary['total_revenue'].sum() * 100

).round(1)

print("=== Regional Performance ===")

print(region_summary.sort_values('total_revenue', ascending=False))# Cell 8: Conclusions (Markdown)Key Findings

- Top Product: Laptops generate the highest revenue despite lower unit volume, driven by their high unit price of $999.99.

- Regional Distribution: Revenue is relatively evenly distributed across regions, suggesting consistent market penetration.

- Recommendation: Focus inventory and marketing efforts on Laptops and Monitors, which represent the highest revenue-per-unit products.

This structured notebook workflow — setup, imports, data loading, exploration, visualization, and conclusions — is the professional standard for data science notebooks.

---

## 11. Common Jupyter Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

### 11.1 Running Cells Out of Order

**The Mistake:** Running cell 5 before cell 3, creating dependencies that do not exist in the written order.

**The Fix:** Always use `Kernel → Restart & Run All` before finalizing and sharing your notebook.

### 11.2 Not Restarting After Large Changes

**The Mistake:** Making significant changes to data loading or preprocessing but not restarting the kernel, so stale data persists in memory.

**The Fix:** Restart the kernel whenever you make changes to data structures, especially early in the notebook.

### 11.3 Too Many Things in One Cell

**The Mistake:** Writing 50 lines of code in a single cell, making it impossible to see intermediate results or debug step by step.

**The Fix:** Keep cells focused on one logical operation. If a cell does more than one thing, split it. Small cells are easier to debug and understand.

### 11.4 No Markdown Documentation

**The Mistake:** A notebook that is all code cells with no explanatory text — essentially an un-commented Python script with different formatting.

**The Fix:** Add Markdown cells before every major section explaining what you are doing and why. A notebook without narrative is difficult to understand even for the person who wrote it, a month later.

### 11.5 Not Saving Before Closing

**The Mistake:** Closing the browser tab without saving, losing recent work.

**The Fix:** Always press **Ctrl+S** before closing. Or, check the auto-save interval in Settings.

### 11.6 Forgetting to Shut Down the Kernel

**The Mistake:** Leaving many notebooks running, each with an active kernel consuming memory.

**The Fix:** When you finish working on a notebook, go to `File → Close and Halt` rather than just closing the browser tab. Or use the Dashboard's "Running" tab to shut down kernels.

---

## 12. Jupyter Notebook Best Practices for Data Science

### 12.1 The Notebook Structure Template

Every data science notebook should follow a consistent structure:

```markdown

# [Project Name]: [Analysis Title]

**Author:** [Your Name]

**Date:** [Date]

**Description:** One-paragraph summary of what this notebook does.

## Table of Contents

1. Setup and Imports

2. Data Loading

3. Data Exploration

4. Data Cleaning

5. Analysis / Modeling

6. Visualization

7. Conclusions

```

### 12.2 Restart & Run All Before Sharing

This cannot be emphasized enough: before sending a notebook to anyone or uploading it to GitHub, always run `Kernel → Restart & Run All`. If the notebook completes without errors, it is self-contained and reproducible. If it crashes, you have a hidden dependency to fix.

### 12.3 Clear Outputs Before Committing to Git

Jupyter notebook outputs (especially charts and large DataFrame previews) can make `.ipynb` files enormous and create messy git diffs. A popular solution is to clear all outputs before committing:

```bash

# Install nbstripout to automatically strip outputs from git commits

pip install nbstripout

nbstripout --install # Configure for the current repository

```

Alternatively, clear outputs manually via `Cell → All Output → Clear` before committing.

### 12.4 Use Meaningful Cell Outputs

Rather than printing a raw DataFrame, add context:

```python

# Less informative

df.head()

# More informative

print(f"Dataset: {df.shape[0]:,} rows × {df.shape[1]} columns")

print(f"Memory usage: {df.memory_usage(deep=True).sum() / 1024**2:.1f} MB")

df.head()

```

### 12.5 Add Progress Indicators for Long Operations

For cells that take more than a few seconds, add progress feedback:

```python

from tqdm.notebook import tqdm

import time

results = []

for item in tqdm(large_list, desc="Processing"):

# ... do work ...

results.append(process(item))

```

---

## Conclusion: Jupyter Notebook Is Your Data Science Home Base

Jupyter Notebook is not just a tool — it is the environment where most data science work actually happens. The combination of interactive code execution, rich output rendering, inline visualizations, and narrative Markdown documentation creates a workflow that is simultaneously more exploratory, more transparent, and more communicable than traditional scripting.

In this article, you learned how Jupyter works technically (the browser-server-kernel architecture), how to install and launch it, the difference between code cells and Markdown cells, keyboard shortcuts that will dramatically accelerate your workflow, how to manage the kernel state to avoid the most common Jupyter pitfalls, and how to structure a professional notebook that tells a coherent data story.

The most important habits to develop are: keep cells small and focused, document with Markdown as you go, restart and run all before sharing, and understand that the kernel's execution order — not the visual order of cells in the notebook — determines what is in memory at any moment.

As you progress through your data science journey, Jupyter will be your constant companion. Every analysis, every experiment, every report will likely start as a Jupyter notebook. The investment you make in mastering it now will pay dividends through every project you undertake.

In the next article, you will discover 10 essential Jupyter Notebook tips that will take your productivity even further.

---

## Key Takeaways

- Jupyter Notebook is a browser-based interactive environment that combines live code, visualizations, equations, and prose in a single `.ipynb` document.

- It works through a three-part system: your browser displays the interface, a local server manages files, and a kernel executes your code.

- Cells are the fundamental unit of a notebook — code cells execute Python, Markdown cells render formatted text, and Raw cells pass through unprocessed.

- The kernel maintains all variables in memory across all executed cells; the execution order (shown by `In [n]` numbers) matters more than the visual cell order.

- Always use `Kernel → Restart & Run All` before sharing a notebook to verify it runs correctly from top to bottom.

- Essential shortcuts: `Shift+Enter` (run and advance), `A`/`B` (insert cell above/below), `M`/`Y` (switch to Markdown/Code), `D,D` (delete cell), `Escape`/`Enter` (switch modes).

- Markdown cells create narrative documentation — use them to structure your notebook with headings, explanations, and conclusions.

- Rich outputs including formatted DataFrames and inline charts appear automatically below code cells.

- Tab completion and `Shift+Tab` for documentation make exploration fast without leaving the notebook.

- Best practices: small focused cells, Markdown documentation, Restart & Run All before sharing, and meaningful outputs with context.