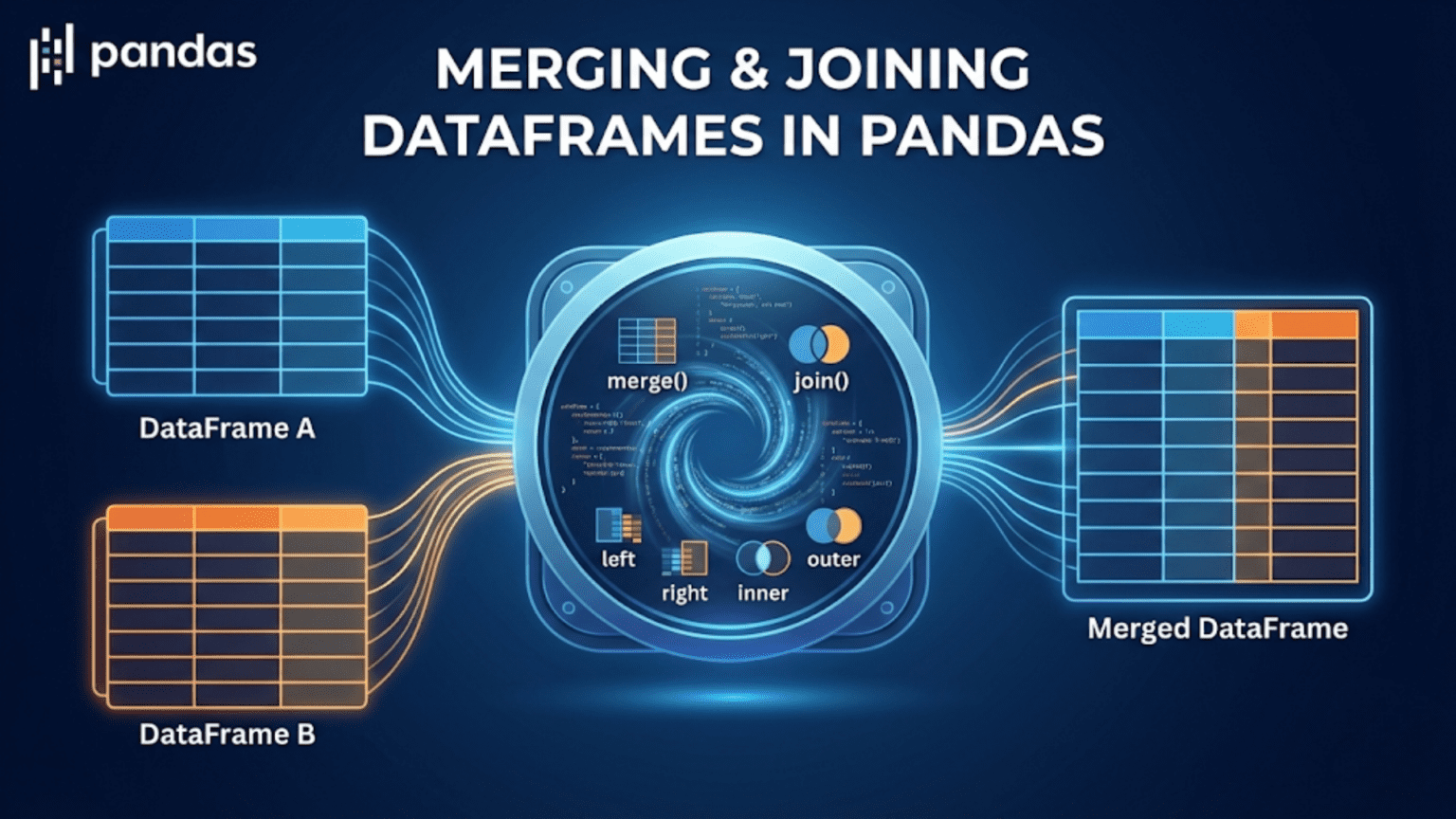

Merging and joining DataFrames in Pandas means combining two or more tables into a single DataFrame based on shared columns or row indices. The primary tools are pd.merge() for SQL-style joins on column values, DataFrame.join() for index-based joins, and pd.concat() for stacking DataFrames vertically or horizontally. Understanding these operations is essential for working with data spread across multiple sources or database tables.

Introduction: Why You Almost Always Work with Multiple Tables

In the real world, data rarely arrives in a single perfectly organized table. Instead, it is spread across multiple sources: customer information lives in one database table, order history in another, product details in a third, and regional data in a fourth. When you need to answer questions that span all of these sources — “What is the average order value per customer segment by region?” — you need to combine them first.

This is exactly what relational databases are designed for. SQL’s JOIN statement is one of the most foundational operations in all of data engineering, and Pandas provides an equally powerful equivalent through pd.merge(), DataFrame.join(), and pd.concat(). If you have worked with SQL before, you will find Pandas merging deeply familiar. If you have not, this article will teach you the concepts from the ground up.

Mastering merging and joining is not just about syntax — it is about understanding the logic of how tables relate to each other, what happens to rows that do not match between tables, and how to diagnose and fix the subtle bugs that merging operations can introduce. This article will equip you with all of that knowledge, from the simplest concatenation to complex multi-key merges and merge validation.

1. The Three Core Tools for Combining DataFrames

Before diving into details, it helps to know which tool to reach for in which situation:

pd.concat() — Stacks DataFrames vertically (adding more rows) or horizontally (adding more columns). No matching logic is involved; it simply places the DataFrames next to each other along an axis.

pd.merge() — Performs SQL-style joins between two DataFrames based on matching values in one or more columns. This is the most powerful and commonly used tool for combining data from different sources.

DataFrame.join() — A convenience wrapper around pd.merge() that is optimized for joining on the row index rather than on column values.

Most data scientists use pd.merge() for the vast majority of combining operations and pd.concat() for stacking. DataFrame.join() is useful for specific index-based scenarios. This article covers all three in depth.

2. Concatenating DataFrames with pd.concat()

2.1 Vertical Concatenation: Stacking Rows

The most common use of pd.concat() is to stack multiple DataFrames with the same column structure on top of each other — for example, combining monthly sales files into a single annual dataset:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

# Three monthly DataFrames with identical structure

jan = pd.DataFrame({

'date': ['2024-01-05', '2024-01-12', '2024-01-20'],

'product': ['Laptop', 'Mouse', 'Monitor'],

'sales': [999.99, 29.99, 349.99]

})

feb = pd.DataFrame({

'date': ['2024-02-03', '2024-02-14', '2024-02-22'],

'product': ['Keyboard', 'Webcam', 'Laptop'],

'sales': [79.99, 89.99, 1099.99]

})

mar = pd.DataFrame({

'date': ['2024-03-08', '2024-03-15', '2024-03-28'],

'product': ['Mouse', 'Monitor', 'Headset'],

'sales': [34.99, 379.99, 149.99]

})

# Concatenate vertically (axis=0 is the default)

q1_sales = pd.concat([jan, feb, mar], axis=0)

print(q1_sales)

# date product sales

# 0 2024-01-05 Laptop 999.99

# 1 2024-01-12 Mouse 29.99

# 2 2024-01-20 Monitor 349.99

# 0 2024-02-03 Keyboard 79.99 ← Index resets to 0!

# 1 2024-02-14 Webcam 89.99

# ...Notice the index — it repeats (0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2, 0, 1, 2) because each DataFrame’s original index is preserved. This can cause problems if you later try to access rows by index. Use ignore_index=True to reset it:

q1_sales = pd.concat([jan, feb, mar], axis=0, ignore_index=True)

print(q1_sales)

# date product sales

# 0 2024-01-05 Laptop 999.99

# 1 2024-01-12 Mouse 29.99

# 2 2024-01-20 Monitor 349.99

# 3 2024-02-03 Keyboard 79.99

# 4 2024-02-14 Webcam 89.99

# 5 2024-02-22 Laptop 1099.99

# 6 2024-03-08 Mouse 34.99

# 7 2024-03-15 Monitor 379.99

# 8 2024-03-28 Headset 149.992.2 Tracking the Source with keys

Sometimes you want to know which original DataFrame each row came from. The keys parameter adds a new outer level to the index:

q1_with_source = pd.concat(

[jan, feb, mar],

keys=['January', 'February', 'March']

)

print(q1_with_source)

# date product sales

# January 0 2024-01-05 Laptop 999.99

# 1 2024-01-12 Mouse 29.99

# 2 2024-01-20 Monitor 349.99

# February 0 2024-02-03 Keyboard 79.99

# ...

# Access a specific month's data

print(q1_with_source.loc['February'])2.3 Concatenation with Mismatched Columns

What happens when the DataFrames you concatenate do not have identical columns? Pandas fills in NaN for missing values:

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'A': [1, 2], 'B': [3, 4]})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'B': [5, 6], 'C': [7, 8]})

result = pd.concat([df1, df2], ignore_index=True)

print(result)

# A B C

# 0 1.0 3 NaN

# 1 2.0 4 NaN

# 2 NaN 5 7.0

# 3 NaN 6 8.0Column B appears in both DataFrames and is populated for all rows. Columns A and C are each missing from one DataFrame, so those positions get NaN. This behavior is equivalent to a SQL FULL OUTER JOIN on the column axis.

To keep only columns that appear in all DataFrames, use join='inner':

result_inner = pd.concat([df1, df2], join='inner', ignore_index=True)

print(result_inner)

# B

# 0 3

# 1 4

# 2 5

# 3 62.4 Horizontal Concatenation: Adding Columns

Concatenating along axis=1 places DataFrames side by side, adding columns:

names = pd.DataFrame({'Name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']})

scores = pd.DataFrame({'Math': [90, 75, 88], 'Science': [85, 92, 79]})

combined = pd.concat([names, scores], axis=1)

print(combined)

# Name Math Science

# 0 Alice 90 85

# 1 Bob 75 92

# 2 Charlie 88 79Horizontal concatenation aligns rows by their index. If the indices do not match, you again get NaN for mismatched positions.

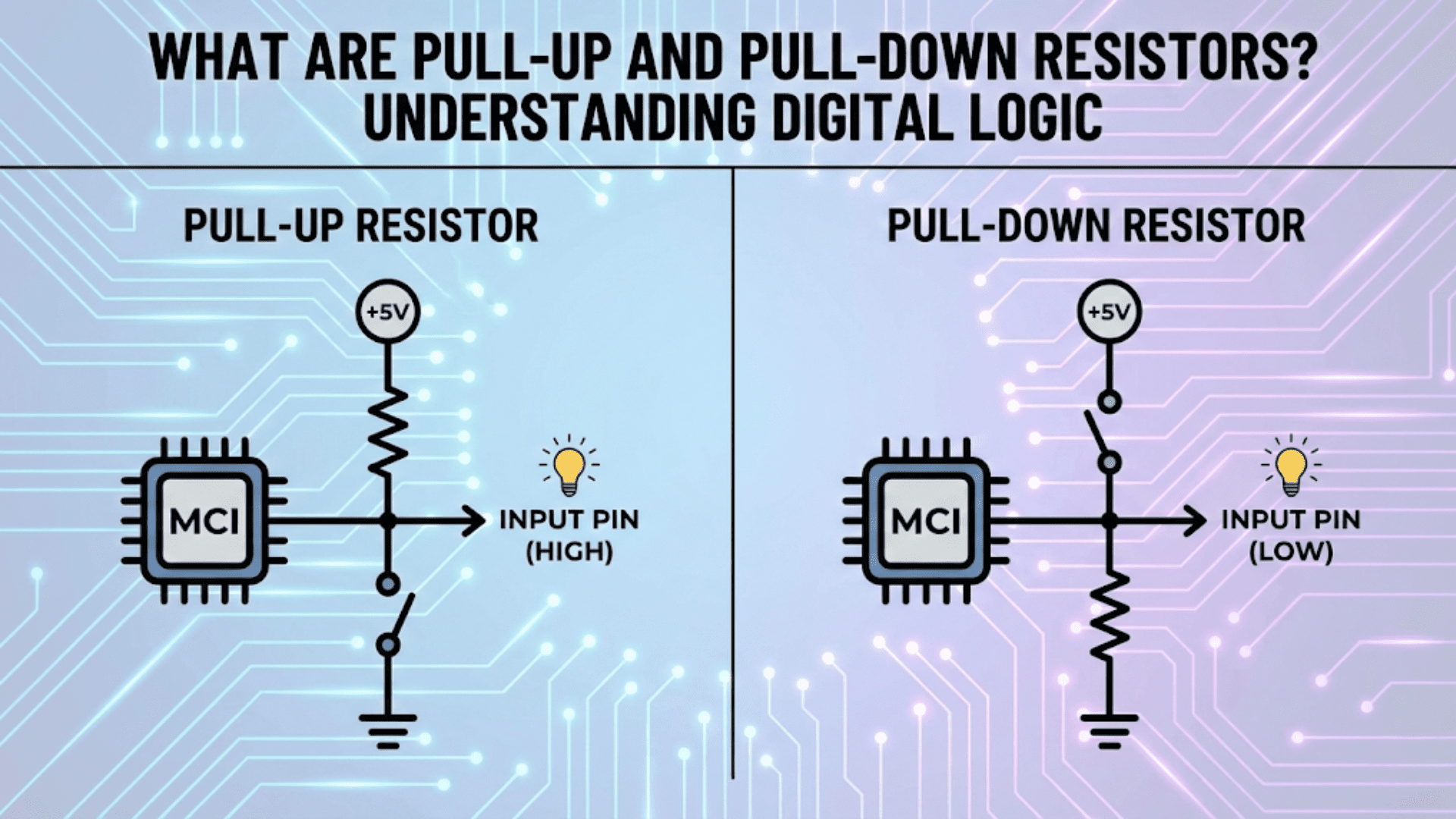

3. Understanding SQL-Style Joins

Before writing any pd.merge() code, you need to understand the four fundamental join types. These concepts come directly from SQL and apply universally to any database or data manipulation tool.

Imagine two tables:

- Left table (A): Contains some rows

- Right table (B): Contains some rows

- Both tables share a common key column

The four join types differ in what happens to rows whose key appears in only one of the tables:

INNER JOIN: Returns only rows where the key exists in both tables. Rows present in only one table are excluded.

LEFT JOIN (LEFT OUTER JOIN): Returns all rows from the left table. Rows from the right table are included only where the key matches; non-matching right rows are excluded, and non-matching left rows get NaN for right-table columns.

RIGHT JOIN (RIGHT OUTER JOIN): The mirror of LEFT JOIN — all rows from the right table are kept, with NaN for left-table columns where there is no match.

FULL OUTER JOIN: Returns all rows from both tables. Rows with no match in the other table get NaN for that table’s columns.

Here is a visual representation with a simple example:

Left table (customers): Right table (orders):

customer_id name customer_id amount

1 Alice 1 150.00

2 Bob 3 200.00

3 Charlie 5 75.00

4 Diana

INNER JOIN (matching rows only):

customer_id name amount

1 Alice 150.00

3 Charlie 200.00

LEFT JOIN (all left rows):

customer_id name amount

1 Alice 150.00

2 Bob NaN ← Bob has no order

3 Charlie 200.00

4 Diana NaN ← Diana has no order

RIGHT JOIN (all right rows):

customer_id name amount

1 Alice 150.00

3 Charlie 200.00

5 NaN 75.00 ← Order 5 has no customer

FULL OUTER JOIN (all rows from both):

customer_id name amount

1 Alice 150.00

2 Bob NaN

3 Charlie 200.00

4 Diana NaN

5 NaN 75.00Understanding these four types deeply — not just their names, but their behavior with non-matching rows — is the foundation of all merge and join operations.

4. Merging DataFrames with pd.merge()

4.1 Basic Merge Syntax

pd.merge(left, right, how='inner', on=None, left_on=None, right_on=None,

left_index=False, right_index=False, suffixes=('_x', '_y'))The most important parameters are:

left,right: The two DataFrames to mergehow: The join type —'inner'(default),'left','right', or'outer'on: The column name(s) to join on (must exist in both DataFrames)left_on/right_on: Used when the key columns have different names in the two DataFramessuffixes: What to append to duplicate column names from each DataFrame

4.2 Inner Join (Default)

import pandas as pd

customers = pd.DataFrame({

'customer_id': [1, 2, 3, 4],

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'Diana'],

'city': ['New York', 'Chicago', 'Los Angeles', 'Houston']

})

orders = pd.DataFrame({

'order_id': [101, 102, 103, 104, 105],

'customer_id': [1, 3, 1, 2, 5],

'amount': [150.00, 200.00, 75.50, 320.00, 90.00]

})

# Inner join: only customers who have placed orders (AND orders with valid customers)

inner_result = pd.merge(customers, orders, on='customer_id', how='inner')

print(inner_result)

# customer_id name city order_id amount

# 0 1 Alice New York 101 150.00

# 1 1 Alice New York 103 75.50

# 2 3 Charlie Los Angeles 102 200.00

# 3 2 Bob Chicago 104 320.00Notice that:

- Customer 4 (Diana) is excluded because she has no orders

- Order 105 is excluded because customer 5 does not exist in the customers table

- Customer 1 (Alice) appears twice because she has two orders — this is correct and expected

4.3 Left Join

# Left join: keep ALL customers, even those without orders

left_result = pd.merge(customers, orders, on='customer_id', how='left')

print(left_result)

# customer_id name city order_id amount

# 0 1 Alice New York 101.0 150.00

# 1 1 Alice New York 103.0 75.50

# 2 2 Bob Chicago 104.0 320.00

# 3 3 Charlie Los Angeles 102.0 200.00

# 4 4 Diana Houston NaN NaN ← No ordersDiana (customer 4) now appears with NaN for order_id and amount. This is the most common join type in practice — you want all records from your primary table and match what you can from the secondary table.

4.4 Right Join

# Right join: keep ALL orders, even those without matching customers

right_result = pd.merge(customers, orders, on='customer_id', how='right')

print(right_result)

# customer_id name city order_id amount

# 0 1.0 Alice New York 101 150.00

# 1 1.0 Alice New York 103 75.50

# 2 3.0 Charlie Los Angeles 102 200.00

# 3 2.0 Bob Chicago 104 320.00

# 4 5.0 NaN NaN 105 90.00 ← No customer recordOrder 105 (customer 5) appears with NaN for name and city because customer 5 does not exist in the customers table. Right joins are less common than left joins — you can always achieve the same result by swapping the DataFrames and using a left join.

4.5 Full Outer Join

# Full outer join: keep ALL rows from both tables

outer_result = pd.merge(customers, orders, on='customer_id', how='outer')

print(outer_result)

# customer_id name city order_id amount

# 0 1.0 Alice New York 101.0 150.00

# 1 1.0 Alice New York 103.0 75.50

# 2 2.0 Bob Chicago 104.0 320.00

# 3 3.0 Charlie Los Angeles 102.0 200.00

# 4 4.0 Diana Houston NaN NaN ← Diana, no orders

# 5 5.0 NaN NaN 105.0 90.00 ← Order 5, no customerThe full outer join combines everything: all customers (including those without orders) and all orders (including those without matching customers).

5. Merging on Columns with Different Names

In real-world datasets, the same conceptual key often has different column names in different tables. For example, one table might call it customer_id and another might call it cust_id. Use left_on and right_on to handle this:

customers = pd.DataFrame({

'customer_id': [1, 2, 3],

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

})

orders = pd.DataFrame({

'order_id': [101, 102, 103],

'cust_id': [1, 3, 2], # Different column name!

'amount': [150.00, 200.00, 320.00]

})

# Use left_on and right_on when key columns have different names

result = pd.merge(

customers, orders,

left_on='customer_id',

right_on='cust_id',

how='inner'

)

print(result)

# customer_id name order_id cust_id amount

# 0 1 Alice 101 1 150.00

# 1 3 Charlie 102 3 200.00

# 2 2 Bob 103 2 320.00Notice that both customer_id and cust_id appear in the result because Pandas keeps both key columns. You can drop the redundant one:

result = result.drop(columns=['cust_id'])

6. Merging on Multiple Keys

Real-world data often requires matching on more than one column simultaneously. For example, you might have sales data split by both product and region, and you want to merge it with a pricing table that also uses both product and region as keys:

# Sales quantities

sales_qty = pd.DataFrame({

'product': ['Laptop', 'Laptop', 'Mouse', 'Mouse'],

'region': ['North', 'South', 'North', 'South'],

'units': [150, 200, 500, 350]

})

# Regional pricing

pricing = pd.DataFrame({

'product': ['Laptop', 'Laptop', 'Mouse', 'Mouse'],

'region': ['North', 'South', 'North', 'South'],

'price': [999.99, 949.99, 29.99, 27.99]

})

# Merge on both product AND region

result = pd.merge(sales_qty, pricing, on=['product', 'region'], how='inner')

result['revenue'] = result['units'] * result['price']

print(result)

# product region units price revenue

# 0 Laptop North 150 999.99 149998.50

# 1 Laptop South 200 949.99 189998.00

# 2 Mouse North 500 29.99 14995.00

# 3 Mouse South 350 27.99 9796.50Multi-key merges ensure that each row matches on all specified columns simultaneously, preventing incorrect row pairings.

7. Handling Duplicate Column Names with suffixes

When both DataFrames contain columns with the same name (other than the key columns), Pandas appends suffixes to distinguish them:

q1_scores = pd.DataFrame({

'student_id': [1, 2, 3],

'score': [85, 92, 78] # Q1 score

})

q2_scores = pd.DataFrame({

'student_id': [1, 2, 3],

'score': [88, 95, 82] # Q2 score

})

# Default suffixes: _x (left) and _y (right)

result_default = pd.merge(q1_scores, q2_scores, on='student_id')

print(result_default)

# student_id score_x score_y

# 0 1 85 88

# 1 2 92 95

# 2 3 78 82

# Custom suffixes: more descriptive

result_named = pd.merge(

q1_scores, q2_scores,

on='student_id',

suffixes=('_q1', '_q2')

)

print(result_named)

# student_id score_q1 score_q2

# 0 1 85 88

# 1 2 92 95

# 2 3 78 82Always use meaningful suffixes when merging DataFrames with overlapping column names. The default _x and _y are cryptic and should be overridden in production code.

8. Index-Based Joins with DataFrame.join()

The DataFrame.join() method is optimized for joining on the row index rather than on regular columns. It is a convenient shorthand that calls pd.merge() under the hood with left_index=True and right_index=True.

8.1 Simple Index Join

# DataFrames with meaningful row indices

employee_info = pd.DataFrame({

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'],

'department': ['Engineering', 'Marketing', 'HR']

}, index=[101, 102, 103])

employee_salary = pd.DataFrame({

'salary': [85000, 72000, 65000],

'years_exp': [4, 7, 8]

}, index=[101, 102, 103])

# Join on the index (default: left join)

result = employee_info.join(employee_salary)

print(result)

# name department salary years_exp

# 101 Alice Engineering 85000 4

# 102 Bob Marketing 72000 7

# 103 Charlie HR 65000 88.2 When to Use join() vs merge()

Use join() when your joining key is already in the index of the right DataFrame. Use merge() for everything else — it is more flexible and explicit. You can always replicate a join() with merge() using left_index=True and/or right_index=True:

# These are equivalent:

employee_info.join(employee_salary)

pd.merge(employee_info, employee_salary,

left_index=True, right_index=True, how='left')8.3 Joining on a Column Against an Index

A common pattern is to join a DataFrame where the key is a regular column against another DataFrame where the key is in the index:

orders = pd.DataFrame({

'order_id': [101, 102, 103],

'product_id': [10, 20, 10],

'quantity': [2, 1, 3]

})

products = pd.DataFrame({

'name': ['Widget', 'Gadget'],

'price': [19.99, 49.99]

}, index=[10, 20]) # product_id is the index

# Join orders (column) against products (index)

result = pd.merge(

orders, products,

left_on='product_id',

right_index=True,

how='left'

)

print(result)

# order_id product_id quantity name price

# 0 101 10 2 Widget 19.99

# 1 102 20 1 Gadget 49.99

# 2 103 10 3 Widget 19.999. Validating Merges

One of the most overlooked but critical features of pd.merge() is the validate parameter. It lets you assert the expected cardinality of the merge — ensuring that the key relationships are what you expect them to be:

# validate='1:1' — asserts one-to-one: each key appears at most once in each table

# validate='1:m' — asserts one-to-many: each key appears once in left, multiple in right

# validate='m:1' — asserts many-to-one: multiple in left, once in right

# validate='m:m' — asserts many-to-many: no restriction (rarely used)

customers = pd.DataFrame({

'customer_id': [1, 2, 3],

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

})

# If customers has duplicate IDs, a 1:m validate will raise an error

try:

result = pd.merge(

customers, orders,

on='customer_id',

how='inner',

validate='1:m' # Assert: one customer → many orders

)

print("Merge validated successfully — customers are unique!")

except pd.errors.MergeError as e:

print(f"Validation failed: {e}")Using validate is an excellent defensive programming practice. Unexpected duplicates in a key column are one of the most common sources of data bugs in production pipelines — validating your merges catches them early.

10. The indicator Parameter: Tracking Row Origins

The indicator=True parameter adds a special column called _merge that tells you where each row in the result came from: 'left_only', 'right_only', or 'both':

customers = pd.DataFrame({'customer_id': [1, 2, 3, 4], 'name': ['Alice','Bob','Charlie','Diana']})

orders = pd.DataFrame({'customer_id': [1, 3, 5], 'amount': [150, 200, 90]})

result = pd.merge(customers, orders, on='customer_id', how='outer', indicator=True)

print(result)

# customer_id name amount _merge

# 0 1.0 Alice 150.0 both

# 1 2.0 Bob NaN left_only ← Bob: customer, no order

# 2 3.0 Charlie 200.0 both

# 3 4.0 Diana NaN left_only ← Diana: customer, no order

# 4 5.0 NaN 90.0 right_only ← Order 5: no customer recordThe _merge indicator is invaluable for:

- Data quality auditing: Identifying records in one table that have no match in the other

- Anti-joins: Finding records present in only one table (a very common pattern)

Anti-Join Pattern

An anti-join finds records in one table that have NO match in another — for example, customers who have never placed an order:

# Anti-join: customers with NO orders

merged = pd.merge(customers, orders, on='customer_id', how='left', indicator=True)

customers_no_orders = merged[merged['_merge'] == 'left_only']['customer_id']

print(customers_no_orders.values)

# [2 4] ← Bob and Diana have never ordered11. Practical Comparison Table: Merge Types and Tools

| Tool / Parameter | Join Type | Key Location | Keeps All Left | Keeps All Right | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

merge(how='inner') | Inner | Column(s) | No | No | Matching records only |

merge(how='left') | Left outer | Column(s) | Yes | No | All primary + matched secondary |

merge(how='right') | Right outer | Column(s) | No | Yes | All secondary + matched primary |

merge(how='outer') | Full outer | Column(s) | Yes | Yes | All records from both tables |

join() | Left (default) | Index | Yes | No | Index-based lookups |

concat(axis=0) | N/A — stacks rows | N/A | N/A | N/A | Combining same-structure tables |

concat(axis=1) | N/A — stacks cols | N/A | N/A | N/A | Adding columns side by side |

merge(indicator=True) | Any | Column(s) | Depends on how | Depends on how | Auditing match quality |

merge(validate=...) | Any | Column(s) | Depends on how | Depends on how | Asserting key uniqueness |

12. Common Merge Problems and How to Debug Them

12.1 Row Explosion: More Rows Than Expected

The most common merge surprise is getting far more rows in the result than in either input DataFrame. This happens when the key column has duplicate values in both tables — creating a many-to-many match:

# Both tables have duplicates in the key column

left = pd.DataFrame({'id': [1, 1, 2], 'val_L': ['a', 'b', 'c']})

right = pd.DataFrame({'id': [1, 1, 2], 'val_R': ['x', 'y', 'z']})

result = pd.merge(left, right, on='id')

print(result)

# id val_L val_R

# 0 1 a x

# 1 1 a y ← a matched BOTH x and y

# 2 1 b x ← b matched BOTH x and y

# 3 1 b y

# 4 2 c zLeft had 3 rows, right had 3 rows, but the result has 5 rows because id=1 appears twice in each table, creating a 2×2=4 combination. Always check df.duplicated(subset=['key_col']).sum() before merging to verify key uniqueness.

# Diagnose potential row explosion before merging

print("Left duplicates:", left.duplicated(subset=['id']).sum())

print("Right duplicates:", right.duplicated(subset=['id']).sum())12.2 Missing Values After a Merge

If you perform a left join and see unexpected NaN values in the right-table columns, it means some key values in the left table have no match in the right table:

# Diagnose: which left keys have no match in right?

unmatched = left[~left['id'].isin(right['id'])]

print("Left keys with no right match:", unmatched['id'].values)12.3 Data Type Mismatches in Key Columns

A subtle but common cause of failed merges is when the key column has different data types in the two DataFrames — for example, integer in one and string in another. Pandas will not automatically convert these:

left = pd.DataFrame({'id': [1, 2, 3], 'val': ['a', 'b', 'c']})

right = pd.DataFrame({'id': ['1', '2', '3'], 'info': ['x', 'y', 'z']}) # strings!

# This inner join produces 0 rows because int != str

result = pd.merge(left, right, on='id')

print(len(result)) # 0 — no matches!

# Fix: align the types first

right['id'] = right['id'].astype(int)

result = pd.merge(left, right, on='id')

print(len(result)) # 3 — correct!Always check df['key_col'].dtype in both DataFrames before merging.

12.4 Whitespace in String Keys

Another subtle bug: string keys that look identical but have trailing or leading spaces will not match:

left = pd.DataFrame({'name': ['Alice', 'Bob '], 'score': [90, 85]}) # 'Bob '

right = pd.DataFrame({'name': ['Alice', 'Bob'], 'grade': ['A', 'B']}) # 'Bob'

result = pd.merge(left, right, on='name')

print(result)

# Only Alice matches! Bob has a trailing space in left.

# Fix: strip whitespace before merging

left['name'] = left['name'].str.strip()

right['name'] = right['name'].str.strip()13. Real-World Example: Building an Analytics Dataset from Multiple Tables

Let us put everything together in a realistic scenario. You are building an e-commerce analytics dataset from four separate tables — the kind of situation you encounter constantly in industry:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(42)

# ── Table 1: Customers ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

customers = pd.DataFrame({

'customer_id': range(1001, 1021),

'name': [f'Customer_{i}' for i in range(1, 21)],

'region': np.random.choice(['North', 'South', 'East', 'West'], 20),

'segment': np.random.choice(['Premium', 'Standard', 'Basic'], 20,

p=[0.2, 0.5, 0.3]),

'join_date': pd.date_range('2022-01-01', periods=20, freq='ME').strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

})

# ── Table 2: Orders ───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

orders = pd.DataFrame({

'order_id': range(5001, 5051),

'customer_id': np.random.choice(range(1001, 1021), 50),

'product_id': np.random.choice([201, 202, 203, 204, 205], 50),

'order_date': pd.date_range('2024-01-01', periods=50, freq='7D').strftime('%Y-%m-%d'),

'quantity': np.random.randint(1, 10, 50)

})

# ── Table 3: Products ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

products = pd.DataFrame({

'product_id': [201, 202, 203, 204, 205],

'product_name': ['Laptop', 'Mouse', 'Monitor', 'Keyboard', 'Webcam'],

'category': ['Electronics', 'Accessories', 'Electronics', 'Accessories', 'Accessories'],

'unit_price': [999.99, 29.99, 349.99, 79.99, 89.99]

})

# ── Table 4: Returns ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

returns = pd.DataFrame({

'order_id': [5001, 5007, 5015, 5023, 5031],

'return_date': ['2024-01-15', '2024-02-20', '2024-04-10', '2024-06-05', '2024-08-01'],

'reason': ['Defective', 'Wrong item', 'Changed mind', 'Defective', 'Wrong size']

})

print("Tables loaded:")

print(f" Customers: {len(customers)} rows")

print(f" Orders: {len(orders)} rows")

print(f" Products: {len(products)} rows")

print(f" Returns: {len(returns)} rows")

# ── Step 1: Join orders with product details ──────────────────────────────────

orders_products = pd.merge(

orders, products,

on='product_id',

how='inner' # Every order must have a valid product

)

orders_products['revenue'] = orders_products['quantity'] * orders_products['unit_price']

print(f"\nAfter orders × products merge: {len(orders_products)} rows")

# ── Step 2: Join with customer information ────────────────────────────────────

full_orders = pd.merge(

orders_products, customers,

on='customer_id',

how='left' # Keep all orders; add customer info where available

)

print(f"After adding customer info: {len(full_orders)} rows")

# ── Step 3: Mark returned orders using indicator ──────────────────────────────

full_orders_with_returns = pd.merge(

full_orders, returns[['order_id', 'reason']],

on='order_id',

how='left',

indicator=True

)

full_orders_with_returns['is_returned'] = (

full_orders_with_returns['_merge'] == 'both'

)

full_orders_with_returns.drop(columns=['_merge'], inplace=True)

print(f"Returns identified: {full_orders_with_returns['is_returned'].sum()} orders")

# ── Step 4: Analysis on the combined dataset ──────────────────────────────────

print("\n=== Revenue by Customer Segment ===")

segment_analysis = full_orders_with_returns.groupby('segment').agg(

total_revenue = ('revenue', 'sum'),

avg_order_value = ('revenue', 'mean'),

total_orders = ('order_id', 'count'),

return_rate_pct = ('is_returned', lambda x: x.mean() * 100)

).round(2)

print(segment_analysis.sort_values('total_revenue', ascending=False))

print("\n=== Revenue by Category and Region ===")

category_region = full_orders_with_returns.pivot_table(

values='revenue',

index='region',

columns='category',

aggfunc='sum',

margins=True,

margins_name='Total'

).round(0)

print(category_region)

print("\n=== Top 5 Customers by Revenue ===")

top_customers = full_orders_with_returns.groupby(['customer_id', 'name', 'segment']).agg(

total_revenue = ('revenue', 'sum'),

order_count = ('order_id', 'count')

).round(2).sort_values('total_revenue', ascending=False).head(5)

print(top_customers)

# ── Step 5: Identify customers with no orders (potential re-engagement targets)

print("\n=== Customers with No Orders (Re-engagement Targets) ===")

all_customers_merge = pd.merge(

customers[['customer_id', 'name', 'segment']],

orders[['customer_id']].drop_duplicates(),

on='customer_id',

how='left',

indicator=True

)

no_orders = all_customers_merge[all_customers_merge['_merge'] == 'left_only']

print(no_orders[['customer_id', 'name', 'segment']])This real-world example demonstrates the complete workflow: starting from four separate normalized tables, building an analysis-ready dataset through a sequence of left and inner joins, using the indicator parameter for return flagging, and then applying groupby aggregations for business insights.

14. Advanced: Concatenating Many Files Efficiently

A very common real-world task is reading many CSV files (one per day, month, or region) and concatenating them into a single DataFrame. The most efficient way is to read them all into a list and concatenate once — not to concatenate inside the loop:

import pandas as pd

import glob

import os

# Pattern: read all CSV files matching a pattern

# (In production, replace the glob pattern with your actual file path)

# EFFICIENT approach: collect all DataFrames first, then concat once

def load_all_csv(pattern):

"""Load all CSV files matching a glob pattern into a single DataFrame."""

files = glob.glob(pattern)

if not files:

raise FileNotFoundError(f"No files found matching: {pattern}")

dfs = []

for filepath in sorted(files):

df = pd.read_csv(filepath)

# Add source file as a column for traceability

df['source_file'] = os.path.basename(filepath)

dfs.append(df)

return pd.concat(dfs, ignore_index=True)

# INEFFICIENT approach (avoid this!):

# result = pd.DataFrame()

# for file in files:

# result = pd.concat([result, pd.read_csv(file)]) # Creates new DataFrame each timeThe inefficient approach creates a new DataFrame on every iteration, which is extremely slow for many files because it copies all previously accumulated data each time. The efficient approach accumulates DataFrames in a list and concatenates just once at the end.

15. Performance Tips for Large Merges

15.1 Merge on Categorical Columns

Just as with groupby(), converting string key columns to category dtype before merging can significantly reduce memory usage and improve performance:

customers['region'] = customers['region'].astype('category')

orders['customer_id'] = orders['customer_id'].astype('int32') # smaller int type15.2 Filter Before Merging

If you only need a subset of rows from one or both tables, filter them before the merge rather than after. This reduces the number of comparisons Pandas needs to make:

# Inefficient: merge everything, then filter

result = pd.merge(large_left, large_right, on='id')

result = result[result['date'] >= '2024-01-01']

# Efficient: filter first, then merge

large_right_filtered = large_right[large_right['date'] >= '2024-01-01']

result = pd.merge(large_left, large_right_filtered, on='id')15.3 Select Only Needed Columns Before Merging

Merging DataFrames with many columns is slower and more memory-intensive than merging a subset. Select only the columns you need before the merge:

# Instead of merging the full customers DataFrame

result = pd.merge(orders, customers, on='customer_id')

# Select only needed columns from customers first

customer_cols = customers[['customer_id', 'name', 'segment']]

result = pd.merge(orders, customer_cols, on='customer_id')Conclusion: Merging Is the Bridge Between Data Sources

The ability to combine data from multiple tables is fundamental to almost every real-world data science project. Raw data almost never arrives in a single table ready for analysis — it lives across normalized database tables, separate CSV exports, API responses, and other sources. Merging and joining is the bridge that brings these sources together into a unified analytical dataset.

In this article, you learned the conceptual foundation: the four SQL join types (inner, left, right, outer) and what happens to non-matching rows in each. You learned pd.concat() for stacking DataFrames vertically and horizontally, pd.merge() for all SQL-style column-based joins, and DataFrame.join() for index-based lookups. You explored advanced features including multi-key merges, custom suffixes, merge validation with validate, and the indicator parameter for auditing match quality and building anti-joins.

Most importantly, you walked through a realistic multi-table e-commerce example that shows how these operations chain together in production data science workflows. The pattern — normalize data into separate tables, build an analysis-ready dataset through a sequence of merges, then aggregate for insights — is one you will use throughout your career.

In the next article, you will learn about the Pandas apply() function, which lets you transform your data using custom Python functions in a flexible and powerful way.

Key Takeaways

pd.concat()stacks DataFrames vertically (same columns, more rows) or horizontally (side by side); useignore_index=Trueto reset the row index after stacking.- The four SQL join types — inner, left, right, and outer — differ in how they handle rows whose key exists in only one of the two tables.

pd.merge()performs SQL-style joins on column values;how='left'is the most common choice, keeping all rows from the primary table.- Use

left_onandright_onwhen the key columns have different names in the two DataFrames. - Use

on=['col1', 'col2'](a list) to merge on multiple key columns simultaneously. - Use

suffixes=('_q1', '_q2')to give meaningful names to overlapping non-key columns instead of the default_xand_y. - The

validateparameter ('1:1','1:m','m:1') asserts the expected key cardinality and catches duplicates before they cause silent row explosions. - The

indicator=Trueparameter adds a_mergecolumn ('both','left_only','right_only') for auditing match quality and building anti-joins. - Row explosion (more result rows than expected) is almost always caused by duplicate key values in one or both tables — always check with

df.duplicated(subset=['key']).sum(). - Data type mismatches and whitespace in string keys are the two most common causes of unexpected zero-match merges — always inspect key columns before merging.

- When loading many files, collect DataFrames in a list and call

pd.concat()once at the end rather than concatenating inside a loop.