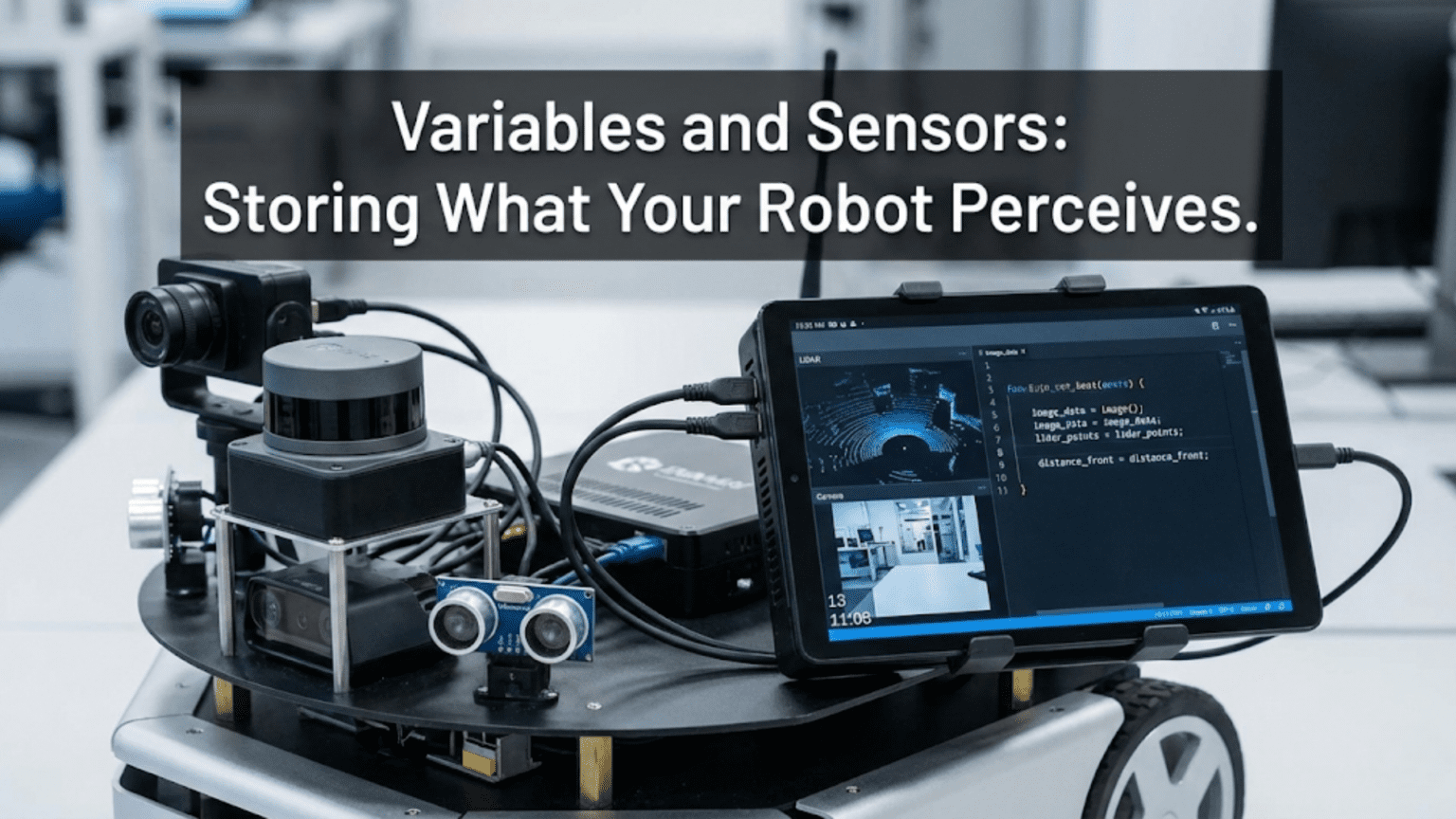

Variables in robotics programming serve as memory containers that store sensor readings and calculated values, allowing your robot to remember what it perceives, compare current conditions to past observations, track changes over time, and make informed decisions based on accumulated information. Understanding variables is essential because sensors produce useless data unless you can store, manipulate, and act upon those readings throughout your program’s execution.

Your robot’s distance sensor detects a wall 15 centimeters ahead, but by the time your code finishes processing that information to make a turning decision, the sensor has already taken fifty more readings and the original value is gone forever. Or perhaps your line-following robot sees the edge of a black line, but your code can’t remember whether the robot was previously on the left or right side of that edge, making it impossible to determine which direction to steer. Maybe your temperature monitoring robot reads 23.5°C, but because you stored it in the wrong type of variable, the decimal precision vanishes and your robot only knows “23 something.”

These frustrating scenarios all stem from the same fundamental issue: improper use of variables to store sensor data. Sensors continuously produce readings—dozens, hundreds, or thousands per second—but each new reading overwrites the last unless you deliberately save values in variables. Variables are your robot’s memory, the containers that hold sensor readings, intermediate calculations, state information, and everything else your program needs to remember. Without proper variable usage, your robot exists in an eternal present moment, unable to remember the past or plan for the future.

This article teaches you how to effectively use variables to store sensor data, choose appropriate data types for different kinds of information, manage memory efficiently, track changes over time, and transform continuous sensor streams into actionable information. Whether you’re building a simple obstacle-avoiding robot or a sophisticated autonomous platform, mastering variables and sensor data storage represents an essential skill that separates robots that blindly react to current readings from robots that intelligently respond based on accumulated understanding.

Understanding Variables: Your Robot’s Memory

Before diving into sensor-specific applications, understanding what variables are and how they work provides the foundation for effective sensor data management.

What Variables Actually Store

Variables are named memory locations that store values. When you create a variable, you’re reserving space in your microcontroller’s RAM (Random Access Memory) to hold information. This information persists as long as your robot has power and your program is running.

Think of variables as labeled boxes where you can put information, retrieve it later, and update it as needed. Unlike permanent storage (like files on a computer), variables in RAM are temporary—they reset when power is lost or the program restarts.

Example:

int distance; // Create variable named "distance"

distance = 25; // Store value 25 in the variable

// Later in code...

int twice = distance * 2; // Retrieve value (25), use it (25*2=50)Why Sensors Need Variables

Sensors produce instantaneous readings that exist only for a moment. If you read a sensor but don’t store the value in a variable, that information vanishes immediately, replaced by the next reading.

Without variables (incorrect):

void loop() {

analogRead(sensorPin); // Read sensor but don't store

// Value is lost! Can't use it for anything

}With variables (correct):

void loop() {

int sensorValue = analogRead(sensorPin); // Read AND store

// Now we can use sensorValue throughout our code

if (sensorValue > 500) {

// Take action based on stored reading

}

}Variable Scope and Lifetime

Where you declare a variable determines where you can use it (scope) and how long it exists (lifetime).

Global variables (declared outside functions):

int globalDistance; // Accessible everywhere

void setup() {

globalDistance = 0; // Can use here

}

void loop() {

globalDistance = measureDistance(); // Can use here

// Value persists between loop iterations

}Local variables (declared inside functions):

void loop() {

int localDistance = measureDistance(); // Only exists in this loop iteration

// At end of loop(), localDistance is destroyed

// Next iteration starts fresh - previous value lost

}For sensor data you need to remember across loop iterations, use global variables or static local variables.

Static local variables (persist between calls but have local scope):

void loop() {

static int count = 0; // Initialized once, persists between iterations

count++; // Increments each loop

Serial.println(count); // 1, 2, 3, 4, ...

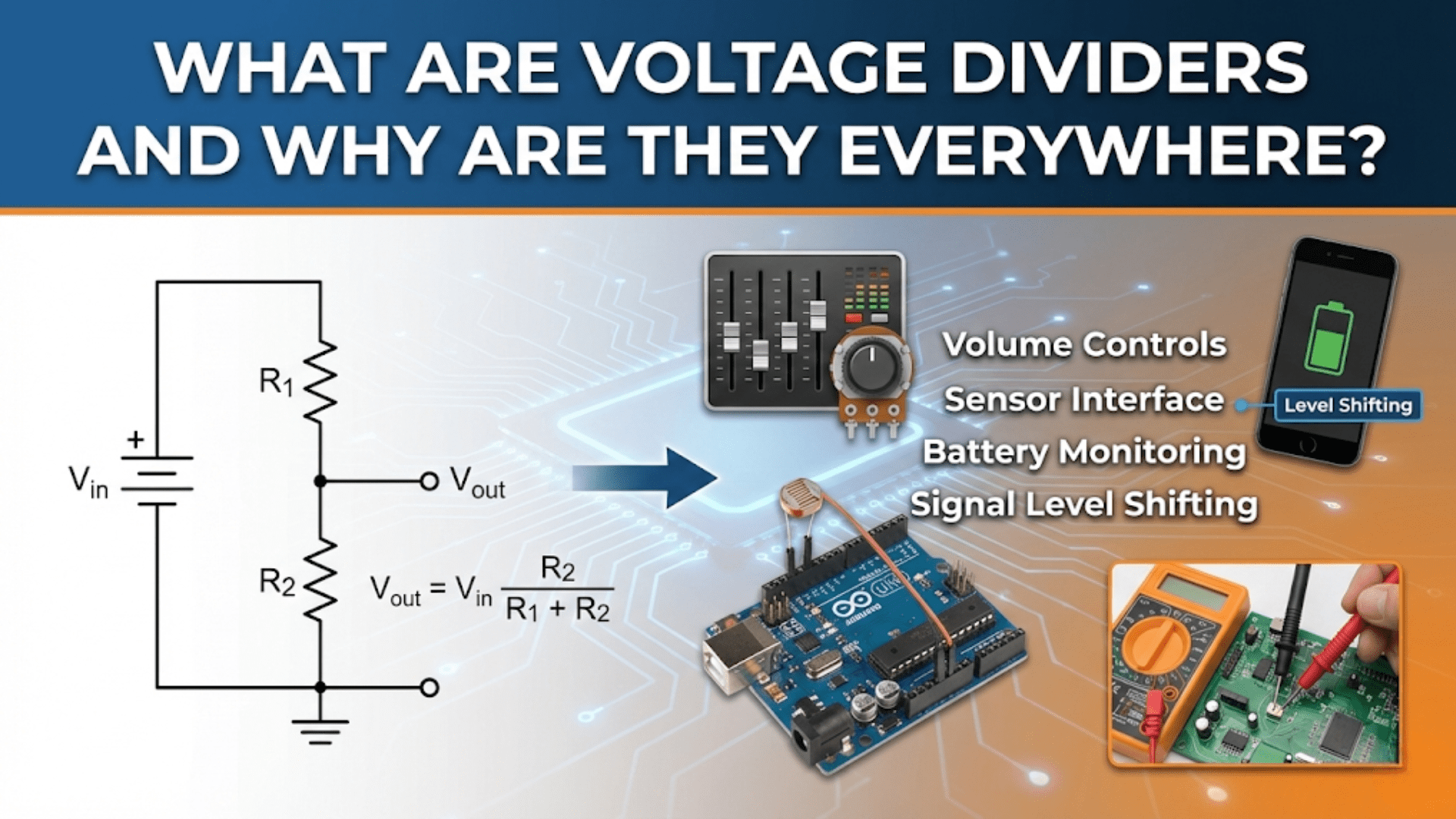

}Data Types: Choosing the Right Container

Different kinds of sensor data require different variable types. Choosing appropriate data types ensures values are stored correctly and memory is used efficiently.

Integer Types: Whole Numbers

int (16-bit signed integer)

- Range: -32,768 to 32,767

- Memory: 2 bytes

- Use for: Counts, ADC readings (0-1023), moderate-sized values

int sensorReading = analogRead(A0); // 0-1023 range

int temperature = -15; // Can store negative values

int motorSpeed = 200; // PWM value 0-255unsigned int (16-bit unsigned)

- Range: 0 to 65,535

- Memory: 2 bytes

- Use for: Values that are never negative, extends positive range

unsigned int largeCount = 50000; // Exceeds normal int range

unsigned int pulseCount = 0; // Never negativelong (32-bit signed integer)

- Range: -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647

- Memory: 4 bytes

- Use for: Large counts, millisecond timestamps, big numbers

long totalDistance = 0; // Accumulates over long periods

long timestamp = millis(); // Milliseconds since startupbyte (8-bit unsigned)

- Range: 0 to 255

- Memory: 1 byte

- Use for: Small values, memory efficiency critical

byte motorPWM = 180; // PWM values only go 0-255

byte sensorArray[10]; // Array of small valuesFloating-Point Types: Decimal Numbers

float (32-bit floating-point)

- Precision: ~6-7 decimal digits

- Memory: 4 bytes

- Use for: Measurements with decimal precision, calculations

float distance_cm = 23.47;

float voltage = 3.87;

float temperature_celsius = 22.5;double (64-bit floating-point on some platforms, 32-bit on Arduino)

- On Arduino: Same as float (4 bytes)

- On other platforms: Higher precision (8 bytes)

double preciseValue = 3.14159265359;

// On Arduino, effectively same as floatBoolean Type: True/False

bool (boolean)

- Values: true or false

- Memory: 1 byte (though only uses 1 bit of information)

- Use for: Flags, states, conditions

bool obstacleDetected = false;

bool batteryLow = true;

bool motorRunning = false;

if (obstacleDetected) {

// Take evasive action

}Character and String Types

char (single character)

- Range: -128 to 127 (or as ASCII character)

- Memory: 1 byte

- Use for: Individual characters, small values

char direction = 'N'; // North, South, East, West

char grade = 'A';String (text string)

- Variable length

- Memory: Depends on length (inefficient on Arduino)

- Use sparingly: Text labels, messages

String robotName = "Explorer-1";

String status = "Running";

// Avoid in performance-critical code - uses dynamic memoryData Type Selection Guide

For sensor readings:

- Digital sensors (HIGH/LOW):

bool - Analog sensors (ADC 0-1023):

int - Converted measurements with decimals:

float - Large accumulating counts:

long

For calculated values:

- Integers only:

intorlong - Need decimal precision:

float - Simple yes/no flags:

bool

For efficiency:

- Small values (0-255):

byte - Larger values:

int - Very large values:

long - Avoid:

String(uses dynamic memory)

Practical Sensor Data Storage Examples

Let’s explore complete examples demonstrating how to properly store and use sensor data in real robotics applications.

Example 1: Distance Sensor with Value Storage

Reading and storing ultrasonic sensor data:

// Ultrasonic sensor pins

const int trigPin = 9;

const int echoPin = 10;

// Variable to store distance reading

float distance_cm;

void setup() {

pinMode(trigPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(echoPin, INPUT);

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

// Measure distance

distance_cm = measureDistance();

// Now we can use the stored value multiple times

Serial.print("Distance: ");

Serial.print(distance_cm);

Serial.println(" cm");

// Use stored value for decision making

if (distance_cm < 20.0) {

Serial.println("OBSTACLE DETECTED!");

} else if (distance_cm < 50.0) {

Serial.println("Caution - object nearby");

} else {

Serial.println("Path clear");

}

delay(100);

}

float measureDistance() {

// Trigger ultrasonic pulse

digitalWrite(trigPin, LOW);

delayMicroseconds(2);

digitalWrite(trigPin, HIGH);

delayMicroseconds(10);

digitalWrite(trigPin, LOW);

// Measure echo time

long duration = pulseIn(echoPin, HIGH);

// Convert to distance (sound travels at 343 m/s)

// distance = (duration / 2) / 29.1 (for cm)

float distance = duration * 0.0343 / 2.0;

return distance;

}Key points:

- Global

distance_cmvariable stores the measurement - Using

floatpreserves decimal precision - Stored value can be used multiple times without re-reading sensor

- Function returns measured value for storage

Example 2: Tracking Sensor History

Storing previous readings to detect changes:

// Light sensor pin

const int lightSensorPin = A0;

// Current and previous readings

int currentLight;

int previousLight = 0;

// Threshold for significant change

const int changeThreshold = 50;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

// Read current light level

currentLight = analogRead(lightSensorPin);

// Calculate change from previous reading

int lightChange = abs(currentLight - previousLight);

// Check if significant change occurred

if (lightChange > changeThreshold) {

Serial.print("Light changed significantly! ");

Serial.print("Was: ");

Serial.print(previousLight);

Serial.print(", Now: ");

Serial.println(currentLight);

if (currentLight > previousLight) {

Serial.println("Getting brighter");

} else {

Serial.println("Getting darker");

}

}

// Store current reading for next iteration

previousLight = currentLight;

delay(200);

}Key points:

- Two variables track current and previous values

- Comparing readings detects changes over time

previousLightupdated at end of loop to remember for next iteration- This pattern essential for edge detection, change monitoring

Example 3: Multiple Sensor Values in Arrays

Storing readings from multiple similar sensors:

// Array of IR sensor pins

const int numSensors = 5;

const int sensorPins[numSensors] = {A0, A1, A2, A3, A4};

// Array to store sensor readings

int sensorValues[numSensors];

// Thresholds

const int lineThreshold = 500;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

// Read all sensors and store in array

for (int i = 0; i < numSensors; i++) {

sensorValues[i] = analogRead(sensorPins[i]);

}

// Display all readings

Serial.print("Sensors: ");

for (int i = 0; i < numSensors; i++) {

Serial.print(sensorValues[i]);

Serial.print(" ");

}

Serial.println();

// Determine line position based on which sensors see line

int linePosition = calculateLinePosition();

Serial.print("Line position: ");

Serial.println(linePosition);

delay(100);

}

int calculateLinePosition() {

// Simple weighted average of sensors seeing line

int sum = 0;

int count = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < numSensors; i++) {

if (sensorValues[i] > lineThreshold) {

sum += i; // Add sensor index

count++;

}

}

if (count > 0) {

return sum / count; // Average position (0-4)

} else {

return -1; // Line not detected

}

}Key points:

- Arrays store multiple related values efficiently

- Loop through array to read all sensors

- Stored values available for complex calculations

- Array indexing provides organized access to each sensor

Example 4: Sensor Fusion with Multiple Data Types

Combining different sensor types with appropriate variable types:

// Sensors

const int distanceSensorPin = A0;

const int lightSensorPin = A1;

const int buttonPin = 2;

// Variables with appropriate types

float distance_cm; // Decimal precision needed

int lightLevel; // Integer sufficient (0-1023)

bool buttonPressed; // True/false state

unsigned long lastReadTime; // Timestamp (large value)

// Timing

const unsigned long readInterval = 100; // Read every 100ms

void setup() {

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT_PULLUP);

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

unsigned long currentTime = millis();

// Only read sensors at specified interval

if (currentTime - lastReadTime >= readInterval) {

// Read and store all sensor values

distance_cm = readDistanceSensor();

lightLevel = analogRead(lightSensorPin);

buttonPressed = (digitalRead(buttonPin) == LOW);

// Update timestamp

lastReadTime = currentTime;

// Display stored values

Serial.print("Distance: ");

Serial.print(distance_cm, 2); // 2 decimal places

Serial.print(" cm, Light: ");

Serial.print(lightLevel);

Serial.print(", Button: ");

Serial.println(buttonPressed ? "PRESSED" : "Released");

// Make decisions based on stored values

makeDecision();

}

}

float readDistanceSensor() {

int rawValue = analogRead(distanceSensorPin);

// Convert ADC to distance (example conversion)

float voltage = rawValue * (5.0 / 1023.0);

float distance = 27.86 * pow(voltage, -1.15); // Example formula

return distance;

}

void makeDecision() {

// Complex decision using all sensor data

if (distance_cm < 15.0 && buttonPressed) {

Serial.println("EMERGENCY STOP - Close obstacle + button");

} else if (distance_cm < 30.0 || lightLevel < 200) {

Serial.println("CAUTION - Low light or obstacle nearby");

} else {

Serial.println("All clear");

}

}Key points:

- Different data types for different sensor types

- All values stored globally for access throughout program

- Timestamp tracking controls read timing

- Stored values enable complex multi-sensor decisions

Common Variable Usage Patterns in Robotics

Certain patterns for using variables with sensors appear repeatedly in robotics code. Mastering these patterns accelerates development.

Pattern 1: Min/Max Tracking

Finding extreme values over time:

int currentReading;

int minValue = 1023; // Initialize to maximum possible

int maxValue = 0; // Initialize to minimum possible

void loop() {

currentReading = analogRead(sensorPin);

// Update min/max if current reading is more extreme

if (currentReading < minValue) {

minValue = currentReading;

}

if (currentReading > maxValue) {

maxValue = currentReading;

}

Serial.print("Current: ");

Serial.print(currentReading);

Serial.print(", Min: ");

Serial.print(minValue);

Serial.print(", Max: ");

Serial.println(maxValue);

delay(100);

}Use cases:

- Sensor calibration (find operating range)

- Peak detection

- Range validation

Pattern 2: Running Average (Smoothing)

Reducing noise by averaging recent readings:

const int numReadings = 10;

int readings[numReadings]; // Array to store readings

int readIndex = 0; // Current position in array

int total = 0; // Running sum

int average = 0; // Calculated average

void loop() {

// Subtract oldest reading from total

total = total - readings[readIndex];

// Read new value

readings[readIndex] = analogRead(sensorPin);

// Add new reading to total

total = total + readings[readIndex];

// Advance to next position

readIndex = readIndex + 1;

if (readIndex >= numReadings) {

readIndex = 0; // Wrap around to beginning

}

// Calculate average

average = total / numReadings;

Serial.print("Raw: ");

Serial.print(readings[readIndex == 0 ? numReadings-1 : readIndex-1]);

Serial.print(", Smoothed: ");

Serial.println(average);

delay(10);

}Use cases:

- Noise reduction

- Smooth control responses

- Stabilizing readings from noisy sensors

Pattern 3: State Change Detection

Detecting transitions (rising/falling edges):

int currentValue;

int lastValue = 0;

bool risingEdgeDetected = false;

bool fallingEdgeDetected = false;

const int threshold = 500;

void loop() {

currentValue = analogRead(sensorPin);

// Detect rising edge (crossed threshold going up)

if (currentValue > threshold && lastValue <= threshold) {

risingEdgeDetected = true;

Serial.println("RISING EDGE - Sensor activated");

}

// Detect falling edge (crossed threshold going down)

if (currentValue <= threshold && lastValue > threshold) {

fallingEdgeDetected = true;

Serial.println("FALLING EDGE - Sensor deactivated");

}

// Store current value for next iteration

lastValue = currentValue;

delay(50);

}Use cases:

- Line detection (crossing line edge)

- Button press/release detection

- Trigger actions on state changes, not continuous states

Pattern 4: Rate of Change (Velocity)

Calculating how quickly values are changing:

float currentPosition;

float previousPosition = 0;

float velocity; // Rate of change

unsigned long currentTime;

unsigned long previousTime = 0;

float deltaTime; // Time elapsed

void loop() {

currentTime = millis();

currentPosition = readSensor(); // Read position sensor

// Calculate time elapsed (convert ms to seconds)

deltaTime = (currentTime - previousTime) / 1000.0;

if (deltaTime > 0) {

// Calculate velocity (change in position / time)

velocity = (currentPosition - previousPosition) / deltaTime;

Serial.print("Position: ");

Serial.print(currentPosition);

Serial.print(", Velocity: ");

Serial.print(velocity);

Serial.println(" units/sec");

}

// Store current values for next iteration

previousPosition = currentPosition;

previousTime = currentTime;

delay(100);

}Use cases:

- Speed calculation

- Acceleration detection

- Predicting future positions

Pattern 5: Threshold Hysteresis

Avoiding rapid toggling near threshold:

int sensorValue;

bool state = false; // Current state

const int upperThreshold = 600;

const int lowerThreshold = 400;

void loop() {

sensorValue = analogRead(sensorPin);

// Only change state if clearly crosses threshold

if (sensorValue > upperThreshold && !state) {

state = true;

Serial.println("State activated");

} else if (sensorValue < lowerThreshold && state) {

state = false;

Serial.println("State deactivated");

}

// State remains stable when value is between thresholds

Serial.print("Value: ");

Serial.print(sensorValue);

Serial.print(", State: ");

Serial.println(state ? "ACTIVE" : "Inactive");

delay(100);

}Use cases:

- Stable state detection near boundaries

- Preventing chattering/oscillation

- Clean on/off transitions

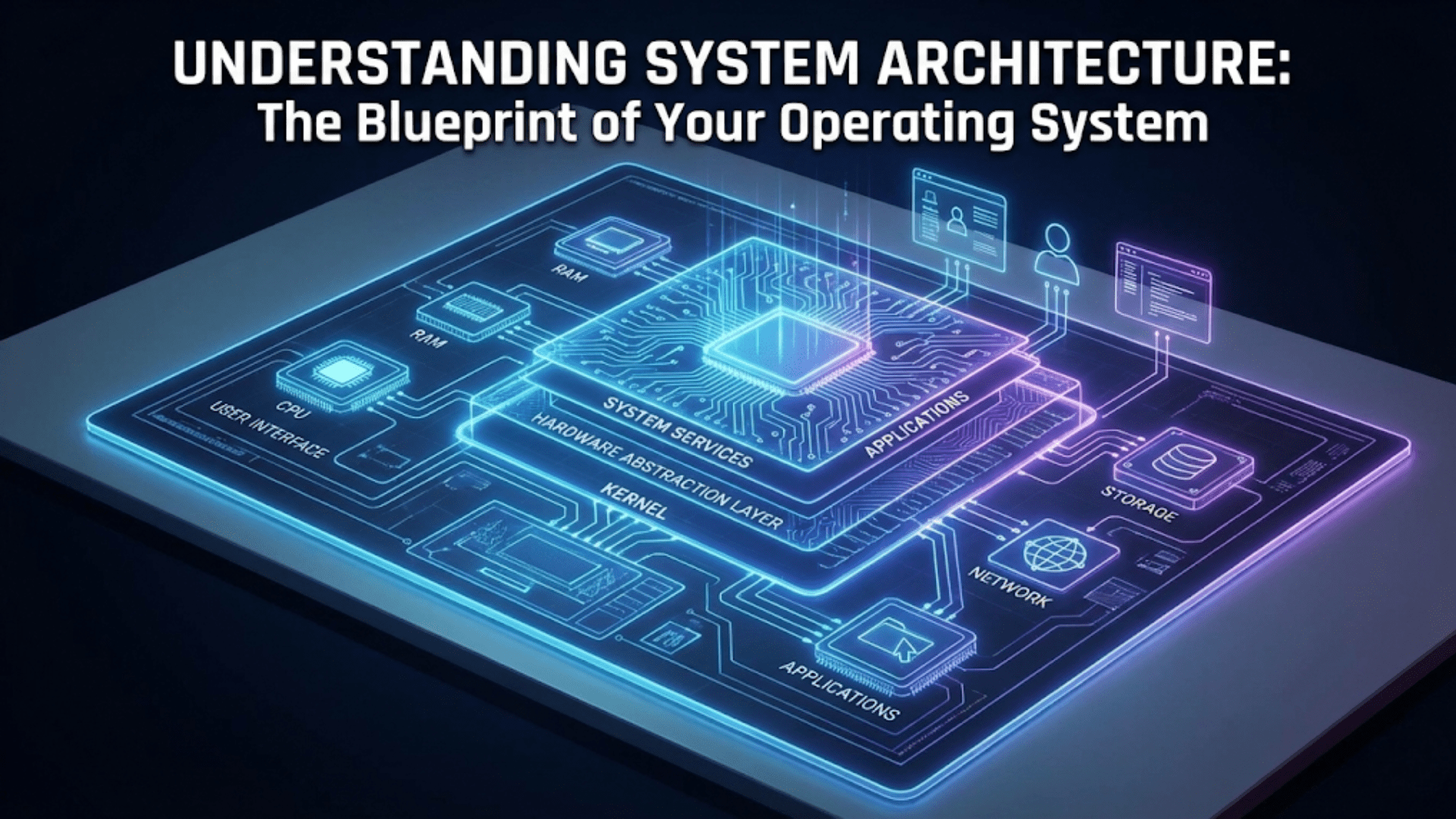

Memory Management: Efficient Variable Usage

Microcontrollers have limited RAM. Understanding memory usage prevents crashes and enables more complex programs.

Arduino Memory Constraints

Arduino Uno:

- Flash (program storage): 32 KB

- SRAM (variables): 2 KB (2048 bytes)

- EEPROM (permanent storage): 1 KB

Your program, all variables, and the stack share just 2 KB of SRAM. Large arrays or many variables can exhaust memory.

Calculating Memory Usage

Each variable consumes memory:

byte value1; // 1 byte

int value2; // 2 bytes

long value3; // 4 bytes

float value4; // 4 bytes

int array[100]; // 200 bytes (100 × 2)

String text = "Hello"; // Variable, ~10+ bytes

// Total: 221+ bytes usedWith only 2048 bytes available, memory fills quickly with large arrays or many variables.

Memory-Efficient Practices

Use smallest appropriate data type:

// Wasteful

long ledState = 0; // 4 bytes for 0/1 value

float counter = 0; // 4 bytes for integer counter

// Efficient

bool ledState = false; // 1 byte

int counter = 0; // 2 bytesUse PROGMEM for constants:

// Wastes SRAM

const char message[] = "This text uses SRAM";

// Saves SRAM (uses Flash instead)

const char message[] PROGMEM = "This text uses Flash";Reuse variables when possible:

// Each calculation uses new variable

int temp1 = analogRead(A0);

int temp2 = temp1 * 2;

int temp3 = temp2 + 100;

// Reuse single variable

int value = analogRead(A0);

value = value * 2;

value = value + 100;Limit array sizes:

// Huge array

int readings[1000]; // 2000 bytes - won't fit!

// Reasonable array

int readings[50]; // 100 bytes - manageableDetecting Memory Problems

Symptoms of memory exhaustion:

- Random crashes or resets

- Variables containing wrong values

- Erratic behavior

- Serial output corruption

Check available memory:

int freeRam() {

extern int __heap_start, *__brkval;

int v;

return (int) &v - (__brkval == 0 ? (int) &__heap_start : (int) __brkval);

}

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

Serial.print("Free RAM: ");

Serial.println(freeRam());

}Aim to keep at least 200-300 bytes free for safety margin.

Advanced Variable Techniques

Beyond basic variable usage, several advanced techniques improve code quality and functionality.

Structures: Grouping Related Variables

Organize related sensor data into structures:

// Define structure type

struct SensorData {

float distance;

int light;

bool obstacle;

unsigned long timestamp;

};

// Create structure variable

SensorData current;

SensorData previous;

void loop() {

// Store complete sensor state

current.distance = measureDistance();

current.light = analogRead(lightSensorPin);

current.obstacle = (current.distance < 20.0);

current.timestamp = millis();

// Access structure members

Serial.print("Distance: ");

Serial.print(current.distance);

Serial.print(" cm at ");

Serial.println(current.timestamp);

// Compare to previous state

if (current.distance < previous.distance) {

Serial.println("Getting closer!");

}

// Save current as previous for next iteration

previous = current;

delay(100);

}Advantages:

- Logical organization

- Easy to copy complete state

- Clear code structure

- Scalable for complex systems

Enumerated Types: Named Constants

Replace magic numbers with meaningful names:

// Define enumeration

enum RobotState {

IDLE,

SEARCHING,

APPROACHING,

GRASPING,

RETURNING,

ERROR

};

// Use enumeration

RobotState currentState = IDLE;

void loop() {

// Read sensors

float distance = measureDistance();

// State machine based on sensor values

switch (currentState) {

case IDLE:

if (distance < 100.0) {

currentState = APPROACHING;

Serial.println("Object detected - approaching");

}

break;

case APPROACHING:

if (distance < 10.0) {

currentState = GRASPING;

Serial.println("Close enough - grasping");

} else if (distance > 150.0) {

currentState = SEARCHING;

Serial.println("Lost object - searching");

}

break;

case GRASPING:

// Grasp object

currentState = RETURNING;

Serial.println("Object grasped - returning");

break;

case RETURNING:

// Return to home

currentState = IDLE;

Serial.println("Returned - idle");

break;

case ERROR:

Serial.println("ERROR STATE");

break;

}

delay(100);

}Advantages:

- Self-documenting code

- Compiler checks for valid values

- Easy to modify states

Volatile Variables: For Interrupt-Modified Variables

When interrupts modify variables used in main code, declare them volatile:

volatile int encoderCount = 0; // Modified by interrupt

void setup() {

attachInterrupt(digitalPinToInterrupt(2), encoderISR, RISING);

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

Serial.print("Encoder count: ");

Serial.println(encoderCount); // Read interrupt-modified variable

delay(1000);

}

void encoderISR() {

encoderCount++; // Increment in interrupt

}The volatile keyword tells the compiler the variable can change unexpectedly, preventing optimization that might cause bugs.

Comparison Table: Data Types for Sensor Values

| Data Type | Size (bytes) | Range | Precision | Best For | Avoid For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bool | 1 | true/false | N/A | Binary sensors, flags, states | Numeric values |

| byte | 1 | 0 to 255 | Integer | Small positive values, PWM | Negative values, large values |

| int | 2 | -32,768 to 32,767 | Integer | ADC readings, counts, most sensors | Very large values, decimals |

| unsigned int | 2 | 0 to 65,535 | Integer | Large positive counts, no negatives | Negative values, decimals |

| long | 4 | -2.1B to 2.1B | Integer | Timestamps, large counts | Memory-constrained, decimals |

| float | 4 | ±3.4×10³⁸ | ~6-7 digits | Distance, temperature, calculations | Exact integer arithmetic |

| String | Variable | Text | N/A | Messages, names | Performance-critical, low-memory |

Common Problems and Solutions

Even experienced programmers encounter variable-related issues when working with sensors.

Problem: Variable Values Not Updating

Symptoms: Variable shows old value; sensor readings not reflected in variable.

Causes:

- Forgot to assign new reading to variable

- Variable declared in wrong scope (local when should be global)

- Reading sensor but not storing result

Solutions:

// Wrong - reading but not storing

analogRead(sensorPin);

Serial.println(sensorValue); // Shows old value

// Correct - store reading in variable

sensorValue = analogRead(sensorPin);

Serial.println(sensorValue); // Shows new valueProblem: Lost Decimal Precision

Symptoms: Calculated values missing decimal places; everything becomes integers.

Causes:

- Using integer variables for floating-point values

- Integer division (dividing two ints produces int)

Solutions:

// Wrong - integer division loses decimals

int a = 5;

int b = 2;

float result = a / b; // result = 2.0 (not 2.5!)

// Correct - convert to float before division

float result = (float)a / (float)b; // result = 2.5

// Or use float variables

float a = 5.0;

float b = 2.0;

float result = a / b; // result = 2.5Problem: Variable Overflow

Symptoms: Large values wrap around to negative or zero; counters reset unexpectedly.

Causes:

- Value exceeds data type’s maximum

- Accumulating values without limit

Solutions:

// Wrong - int overflow

int count = 32000;

count = count + 1000; // Overflows, becomes -32536!

// Correct - use larger data type

long count = 32000;

count = count + 1000; // No overflow, becomes 33000

// Or reset periodically

if (count > 30000) {

count = 0; // Reset before overflow

}Problem: Memory Exhaustion

Symptoms: Random crashes; variables containing wrong values; erratic behavior.

Causes:

- Too many variables

- Large arrays

- String usage

- Memory leaks

Solutions:

// Check free memory

Serial.print("Free RAM: ");

Serial.println(freeRam());

// Reduce array sizes

int bigArray[500]; // Too large for Uno

int smallArray[50]; // More reasonable

// Avoid String, use char arrays

String text = "This uses dynamic memory"; // Bad

char text[] = "This uses static memory"; // GoodConclusion: Variables as the Foundation of Robot Intelligence

Variables transform sensors from simple input devices into the foundation of robot intelligence. Raw sensor readings mean nothing unless you store them, compare them to thresholds, track how they change over time, combine them with other sensor data, and use them to make informed decisions. Variables are the memory that allows your robot to learn from the past, understand the present, and plan for the future.

Every sophisticated robot behavior builds on proper variable usage: line-following compares current sensor positions to previous readings; obstacle avoidance tracks distances over time to detect approaching objects; autonomous navigation maintains maps of visited locations; feedback control compares desired states to actual sensor measurements. None of these capabilities exist without variables storing the right information in the right types at the right scope.

The skills you’ve developed in this article—choosing appropriate data types, managing memory efficiently, implementing common patterns like averaging and edge detection, organizing data with structures—apply universally across robotics programming. Whether you’re working with Arduino, Raspberry Pi, professional embedded systems, or any other platform, variables store sensor data the same way. The specific syntax might vary slightly, but the concepts remain identical.

Start simple with your variable usage: store a single sensor reading, use it to make a decision, print it for debugging. As you gain confidence, add complexity: track multiple sensors, implement averaging for noise reduction, detect state changes, calculate rates of change. Each project teaches new patterns and reinforces fundamentals, building intuition for what variables you need and how to use them effectively.

Remember that variables are not just passive containers—they’re active tools for transforming continuous sensor streams into discrete, actionable information. A raw stream of distance measurements becomes “obstacle detected” when stored values cross thresholds. Fluctuating light readings become “bright” or “dark” states when you apply hysteresis. Noisy position data becomes smooth, stable values when you implement averaging. Variables are where the transformation from sensing to understanding happens.

Most importantly, proper variable usage makes your code readable, maintainable, and debuggable. Well-named variables with appropriate types serve as self-documentation, making clear what information you’re tracking and why. When problems occur (and they will), examining variable values through serial output reveals exactly what your robot perceives and how it’s processing that information. This visibility into your robot’s “thought process” accelerates debugging and deepens understanding.

Your robot’s sensors are its eyes, ears, and touch—but variables are its memory and understanding. Master variables, and you master the essential skill that transforms sensor data into robot intelligence.