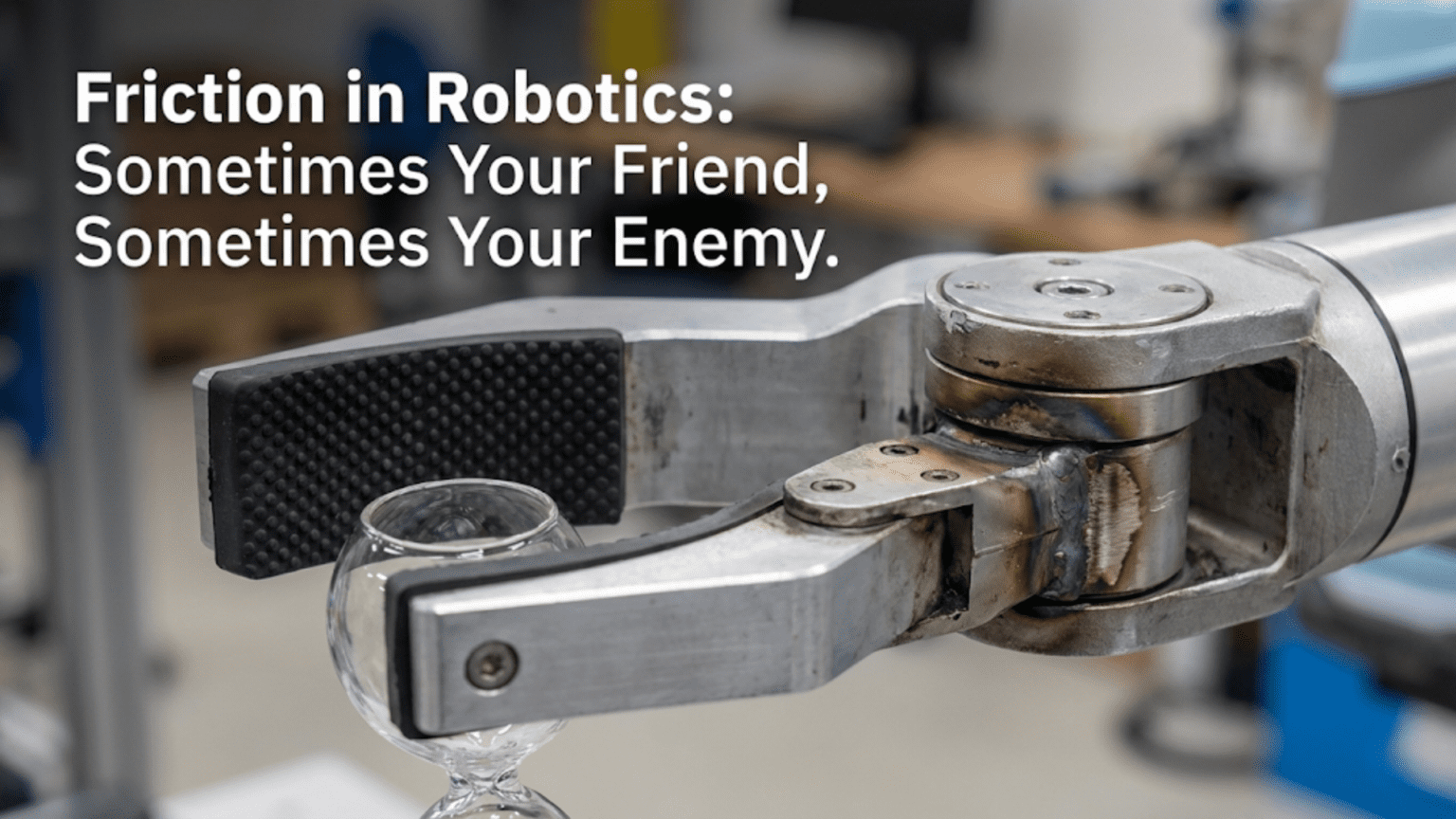

Friction in robotics is the resistance force that occurs when surfaces slide or attempt to slide against each other, acting as both an essential enabler of traction that allows wheels and legs to grip surfaces and push robots forward, and as an unwanted energy drain that causes inefficiency in gears, bearings, and joints. Successful robot design requires understanding when to maximize friction for grip and when to minimize it for efficiency.

You’ve carefully designed your robot, selected powerful motors with perfect gear ratios, programmed smooth control algorithms, and confidently placed it on the floor for testing. You command it to drive forward, but instead of moving, the wheels just spin uselessly, polishing the floor to a shine. Or perhaps your robot moves, but the battery drains far faster than calculations predicted, and the motors feel uncomfortably warm after just minutes of operation. In both scenarios, you’re encountering friction—the invisible force that can make or break your robot’s performance.

Friction is perhaps the most paradoxical force in robotics. Without it, your wheeled robot couldn’t move forward—the wheels would spin endlessly without pushing against the ground. Your robot arm couldn’t grip objects—they’d slip through the gripper like trying to hold an ice cube with oiled fingers. Yet friction also steals energy from every moving part, heating up gearboxes, wearing down components, and draining batteries faster than ideal efficiency would predict. Understanding this dual nature transforms you from someone confused by unpredictable robot behavior into someone who deliberately engineers friction into and out of designs exactly where needed.

This article explores friction’s complex role in robotics, teaching you when to embrace it, when to fight it, and how to manipulate it for optimal performance. You’ll learn the physics underlying different friction types, practical techniques for increasing traction when you need it, methods for reducing unwanted resistance, and how to diagnose friction-related problems in your robots. Whether you’re building your first line-following robot or designing sophisticated mobile manipulators, mastering friction separates adequate designs from excellent ones.

The Physics of Friction: Understanding the Fundamentals

Before diving into practical applications, understanding friction’s physical origins helps you predict its behavior and engineer appropriate solutions. Friction isn’t a single simple phenomenon but rather several related effects with different characteristics and causes.

At the microscopic level, even apparently smooth surfaces contain countless tiny peaks and valleys. When two surfaces contact each other, these microscopic irregularities interlock, creating resistance to sliding motion. Additionally, molecular forces between surfaces create adhesion—atoms in the surfaces weakly bond to each other, requiring force to break these bonds and allow motion.

The combination of mechanical interlocking and molecular adhesion creates the friction force we observe macroscopically. The rougher the surfaces at microscopic scales, generally the higher the friction. The stronger the molecular interactions between surface materials, the greater the adhesive component of friction.

Static Versus Kinetic Friction

Friction manifests in two distinct forms: static friction (when surfaces aren’t moving relative to each other) and kinetic friction (when surfaces are sliding).

Static friction is the force that resists the initial motion between surfaces at rest. When you try to push a heavy robot across the floor, you must overcome static friction to get it moving. Static friction can vary from zero up to a maximum value determined by the surfaces and normal force pressing them together. As you push harder on your stationary robot, static friction increases to match your push—until you reach the maximum static friction, at which point the robot suddenly breaks free and begins sliding.

This maximum static friction follows a simple relationship:

F_static_max = μ_s × N

Where:

- F_static_max is the maximum static friction force

- μ_s is the coefficient of static friction (a property of the surface materials)

- N is the normal force (how hard the surfaces press together)

For a 2 kg robot sitting on a floor, the normal force equals its weight: N = 2 kg × 9.81 m/s² ≈ 19.6 N. If the rubber-on-concrete coefficient is μ_s = 0.9, the maximum static friction is:

F_static_max = 0.9 × 19.6 N = 17.64 N

You must push with more than 17.64 N to overcome static friction and start the robot sliding.

Once surfaces begin sliding, kinetic friction takes over. Kinetic friction remains relatively constant regardless of sliding speed (within normal ranges) and is typically lower than maximum static friction. The kinetic friction equation is similar:

F_kinetic = μ_k × N

The coefficient of kinetic friction (μ_k) is usually 20-50% lower than the static coefficient for the same materials. Using the previous example with μ_k = 0.7:

F_kinetic = 0.7 × 19.6 N = 13.72 N

Once your robot starts moving, it takes only 13.72 N to keep it sliding at constant speed—less than the 17.64 N needed to start motion. This difference between static and kinetic friction explains why objects suddenly lurch when they break free from rest—the required force drops once motion begins.

Rolling Friction: A Special Case

When wheels or balls roll rather than slide, they experience rolling friction (sometimes called rolling resistance), which follows different principles. Rolling friction is typically much lower than sliding friction—this is exactly why wheels are so effective for transportation.

Rolling friction occurs because:

- The wheel slightly deforms where it contacts the surface, creating a small depression

- The surface slightly deforms under the wheel’s weight

- These deformations must continuously form ahead of the wheel and recover behind it, consuming energy

Rolling friction depends on wheel material stiffness, surface hardness, wheel radius, and load. Harder wheels on hard surfaces have lower rolling friction. Larger diameter wheels have lower rolling friction than small wheels carrying the same load.

The rolling friction force is:

F_rolling = C_rr × N

Where C_rr is the coefficient of rolling resistance. Typical values:

- Hard rubber wheel on smooth concrete: C_rr ≈ 0.01-0.02

- Pneumatic tire on asphalt: C_rr ≈ 0.02-0.04

- Metal wheel on metal rail: C_rr ≈ 0.001-0.002

- Soft rubber on carpet: C_rr ≈ 0.05-0.10

Compare rolling friction to sliding friction for rubber on concrete:

- Sliding: μ_k ≈ 0.7 (70% of normal force)

- Rolling: C_rr ≈ 0.02 (2% of normal force)

Rolling friction is roughly 35 times lower than sliding friction! This dramatic difference explains why wheeled vehicles dominate transportation—they’re far more efficient than dragging loads across surfaces.

Viscous Friction: Drag in Fluids and Lubricants

When objects move through fluids (including air) or when lubricated surfaces slide against each other, viscous friction dominates. Unlike dry friction, viscous friction increases with velocity—moving faster creates more resistance.

For robots, viscous friction appears in:

- Air resistance on fast-moving robots

- Hydraulic and pneumatic cylinders

- Lubricated bearings and gears

- Motors (internal air resistance and bearing lubrication)

The viscous friction force follows:

F_viscous = b × v

Where b is a damping coefficient (determined by fluid properties and geometry) and v is velocity. Double the speed, and you double the viscous friction force.

For most hobby robots traveling at low speeds (under 5 m/s), air resistance is negligible. But for high-speed competition robots, drones, or underwater vehicles, viscous drag becomes a dominant force requiring careful design consideration.

When Friction Is Your Friend: Traction and Grip

In many robotics applications, you actively want maximum friction. Without adequate friction between wheels and ground, or between grippers and objects, your robot can’t perform its intended functions. Understanding how to maximize friction where you need it is essential for capable robot designs.

Wheel Traction: Moving Your Robot Forward

When your robot’s drive wheels rotate, friction between the wheel surface and ground creates the forward force that propels your robot. This traction force cannot exceed the maximum static friction between wheel and surface:

F_traction_max = μ_s × (weight on drive wheels)

If you command your motors to produce more torque than this maximum traction can support, the wheels spin without gripping—you’re experiencing wheel slip. This wastes energy and prevents forward motion.

For a two-wheel-drive robot weighing 3 kg with 60% weight on the driven rear wheels:

Weight on drive wheels = 3 kg × 0.6 = 1.8 kg Normal force on drive wheels = 1.8 kg × 9.81 m/s² = 17.66 N

With rubber wheels on wood floor (μ_s ≈ 0.5): F_traction_max = 0.5 × 17.66 N = 8.83 N

If your robot has 8 cm diameter wheels, they have a 4 cm radius (0.04 m). If motor torque produces 1 N⋅m at the wheels, the force trying to push the robot forward is:

F_motor = torque ÷ radius = 1 N⋅m ÷ 0.04 m = 25 N

Your motors are trying to push with 25 N, but maximum traction is only 8.83 N—the wheels will definitely slip. Solutions include:

- Reduce motor torque (lower power or higher gear ratio trading torque for speed)

- Increase traction (better tires, more weight on drive wheels, different surface)

- Increase driven wheel count (four-wheel drive shares force across more wheels)

Calculating Required Traction

For any robot task, you can calculate minimum required traction. The robot must overcome:

- Rolling friction: F_rolling = C_rr × total_weight

- Acceleration: F_acceleration = mass × acceleration

- Slope climbing: F_slope = weight × sin(slope_angle)

- Payload pushing/pulling: F_payload

Total required traction = F_rolling + F_acceleration + F_slope + F_payload

For a 2 kg robot climbing a 15-degree slope with 0.5 m/s² acceleration and C_rr = 0.02:

F_rolling = 0.02 × (2 kg × 9.81 m/s²) = 0.392 N F_acceleration = 2 kg × 0.5 m/s² = 1.0 N F_slope = (2 kg × 9.81 m/s²) × sin(15°) = 19.62 N × 0.259 = 5.08 N F_total = 0.392 + 1.0 + 5.08 = 6.47 N

Your traction must exceed 6.47 N. If you have rubber wheels on concrete (μ_s = 0.9) with all weight on drive wheels:

Available traction = 0.9 × 19.62 N = 17.66 N

You have 17.66 N available versus 6.47 N required—a safety factor of 2.7×, which is good design practice.

Strategies for Maximizing Traction

When calculations show insufficient traction for your requirements, several approaches can help:

Higher-friction materials: Replace smooth plastic wheels with rubber or silicone. Different rubber compounds offer different coefficients:

- Hard plastic: μ_s ≈ 0.2-0.3

- Standard rubber: μ_s ≈ 0.5-0.8

- Soft silicone rubber: μ_s ≈ 0.8-1.2

- Specialized traction compounds: μ_s ≈ 1.0-1.5

Some competition robots use ultra-soft tires with friction coefficients exceeding 1.0, meaning the traction force can actually exceed the robot’s weight!

Increased normal force: Adding weight to drive wheels increases normal force, proportionally increasing traction. This can be accomplished by:

- Shifting center of mass toward drive wheels

- Adding ballast specifically over drive wheels

- Design geometry that naturally loads drive wheels more heavily

Surface texture: Tread patterns and surface roughness increase mechanical interlocking. Deep treads work well on soft surfaces (dirt, carpet) where the tread can dig in. On hard smooth surfaces, softer rubber with larger contact patches often works better than deep treads.

More drive wheels: Four-wheel drive distributes required traction across more contact points. If two driven wheels slip at 10 N each, adding two more drive wheels doubles available traction to 40 N (assuming weight distributes evenly).

Active traction control: Sophisticated robots can sense wheel slip (using encoders to detect speed differences between wheels and ground) and reduce motor power to prevent slipping. This maximizes traction without exceeding available grip—similar to anti-lock braking systems in cars.

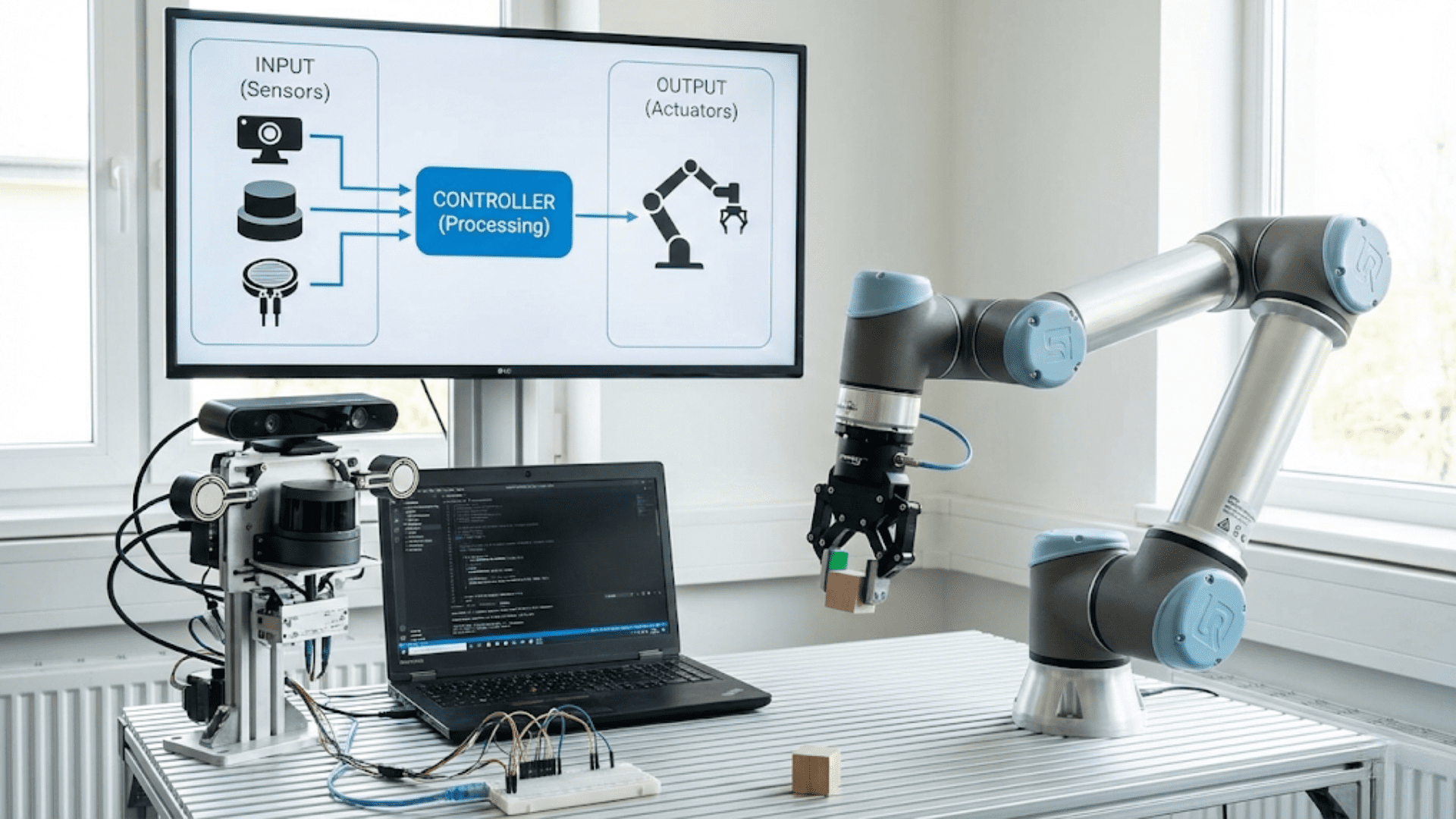

Gripper Friction: Holding Objects Securely

Robot grippers rely on friction to prevent held objects from slipping. The maximum weight a gripper can hold depends on:

- Normal force (how hard the gripper squeezes)

- Friction coefficient between gripper pads and object

- Geometry (parallel-jaw versus encompassing grippers)

For a simple parallel-jaw gripper with two opposing contact points:

Maximum holding force = 2 × (gripper_force × μ_gripper-object)

If your gripper squeezes with 5 N force and has rubber pads (μ = 0.6) gripping a plastic object:

Holding force = 2 × (5 N × 0.6) = 6 N

This can support approximately 0.61 kg (6 N ÷ 9.81 m/s²) before the object slips from the gripper.

To hold heavier objects:

- Increase gripper force (stronger actuators, higher gear ratios)

- Use higher-friction gripper pads (soft rubber, silicone, textured surfaces)

- Add more contact points (three-jaw grippers, encompassing grippers)

- Design gripper geometry to support object mechanically, not just through friction

Many professional robot grippers use compliant materials that conform to object shapes, maximizing contact area and friction. Some use vacuum suction or electromagnetic gripping to avoid relying solely on friction.

When Friction Is Your Enemy: Minimizing Resistance

While friction provides essential traction, it also creates unwanted resistance in bearings, gears, joints, and sliding mechanisms. Reducing this parasitic friction improves efficiency, extends battery life, and reduces wear.

Friction Losses in Mechanical Systems

Every moving part in your robot experiences friction that consumes energy and generates heat. The cumulative effect can be substantial—a robot with many high-friction joints might waste 30-50% of motor power just overcoming internal friction.

Consider a robot arm with four joints, each using plain bushings with friction coefficient μ = 0.15. Each joint carries different portions of the arm’s weight:

- Shoulder joint: supporting 2 kg at 15 cm radius → friction torque ≈ 0.44 N⋅m

- Elbow joint: supporting 1 kg at 10 cm radius → friction torque ≈ 0.15 N⋅m

- Wrist joint: supporting 0.3 kg at 5 cm radius → friction torque ≈ 0.02 N⋅m

- Gripper rotation: supporting 0.1 kg at 3 cm radius → friction torque ≈ 0.004 N⋅m

Total friction torque ≈ 0.61 N⋅m

If your arm moves at an average angular velocity of 0.5 radians/second:

Power loss to friction = total_friction_torque × angular_velocity Power loss = 0.61 N⋅m × 0.5 rad/s = 0.305 watts

This might seem small, but if your motors provide 2 watts of useful work, friction is consuming 15% of your power. Over a 30-minute operation, that’s:

Energy wasted = 0.305 W × 1800 seconds = 549 joules

With a 7.4V, 2000 mAh battery (≈53,280 joules capacity), this friction alone would drain about 1% of your battery. When you add friction from all the robot’s systems, the cumulative effect becomes significant.

Gearbox Friction: The Efficiency Challenge

Gearboxes inherently involve friction between meshing teeth and in the bearings supporting gear shafts. As discussed in the gearbox article, different gear types have different efficiencies:

- Spur gears: 95-98% efficient per stage

- Planetary gears: 90-95% per stage

- Worm gears: 40-90% depending on design

These percentages represent how much power makes it through to the output versus being lost to friction. A two-stage spur gearbox at 96% per stage has overall efficiency:

Overall efficiency = 0.96 × 0.96 = 0.922 or 92.2%

This means 7.8% of your motor’s power becomes heat in the gearbox. For a 10-watt motor, you lose 0.78 watts (7.8% of 10W) continuously during operation. Over an hour, that’s 2,808 joules wasted as heat.

Minimizing gearbox friction requires:

Proper lubrication: Grease or oil fills microscopic gaps between gear teeth, reducing metal-on-metal contact. However, too much lubricant creates viscous drag, especially at high speeds. Use the minimum amount needed to coat surfaces.

Gear quality: Precisely manufactured gears with accurate tooth profiles mesh smoothly with minimal sliding friction. Cheap gears with rough teeth or incorrect geometry waste more energy.

Appropriate gear types: For high-efficiency applications, prefer spur or planetary gears over worm gears. Use worm gears only when their self-locking behavior or high reduction ratio justifies the efficiency sacrifice.

Proper alignment: Misaligned gears experience binding and excessive friction. Ensure gear shafts are parallel (for spur gears) or correctly angled (for bevel gears), and that gear mesh depth is appropriate—not too tight, not too loose.

Bearing Selection: Rolling Versus Sliding

Bearings support rotating shafts and determine how much friction the rotation encounters. The choice between bearing types dramatically affects friction:

Plain bushings (sleeve bearings): The shaft rotates inside a cylindrical sleeve, with sliding friction between shaft and bushing. These are cheap and compact but have relatively high friction (μ ≈ 0.1-0.2 with lubrication). They work adequately for low-speed, low-load applications but waste energy at higher speeds.

Ball bearings: Steel balls roll between inner and outer races, replacing sliding friction with rolling friction. This reduces friction by 10-20× compared to plain bushings. Ball bearings are more expensive and slightly larger but dramatically improve efficiency for high-speed or high-load applications.

Needle bearings: Similar to ball bearings but using cylindrical rollers instead of balls. They handle higher radial loads in smaller spaces but typically cost more.

For a shaft rotating at 1000 RPM with 50 N radial load and 1 cm radius:

Plain bushing (μ = 0.15): Friction torque = μ × load × radius = 0.15 × 50 N × 0.01 m = 0.075 N⋅m Power loss = torque × angular_velocity = 0.075 × (1000 RPM × 2π/60) = 7.85 watts

Ball bearing (equivalent friction μ ≈ 0.002): Friction torque = 0.002 × 50 N × 0.01 m = 0.001 N⋅m Power loss = 0.001 × 104.7 rad/s = 0.105 watts

The ball bearing wastes only 0.105 watts versus the bushing’s 7.85 watts—a 75× improvement! For high-speed applications, ball bearings are essential for acceptable efficiency.

Lubrication: The Art of Controlled Friction

Lubricants reduce friction by creating a thin film between moving surfaces, preventing direct contact. Proper lubrication can reduce friction by 50-90% depending on the application.

Different lubricants suit different applications:

Light machine oil: Low viscosity allows it to penetrate tight spaces. Good for high-speed gears and bearings. Provides minimal friction but may need frequent reapplication as it evaporates or gets flung out.

Grease (lithium or synthetic): Higher viscosity keeps it in place longer. Good for moderate-speed gears and bearings. Provides sustained lubrication but can create viscous drag at very high speeds.

Dry lubricants (PTFE, graphite): Leave a slippery coating without liquid residue. Good for dusty environments where liquid lubricants would attract contamination. Provide less friction reduction than oils but don’t collect dirt.

Specialty lubricants: Some applications need specific lubricants—for example, silicone grease for plastic gears (petroleum-based oils can degrade some plastics), or high-temperature grease for motors that get hot.

Apply lubricants sparingly. A thin film coating surfaces is ideal—excess lubricant creates churning losses without improving lubrication. For gears, apply a small amount to teeth and run the mechanism to distribute it evenly. For bearings, pack with grease according to manufacturer specifications (typically 30-50% full, not completely packed).

Surface Material Interactions: The Friction Coefficient Matrix

Different material pairings produce vastly different friction coefficients. Understanding these relationships helps you select appropriate materials for wheels, gripper pads, bearing surfaces, and sliding mechanisms.

Common Material Pair Friction Coefficients

The following table summarizes typical static friction coefficients for material pairs commonly encountered in robotics:

| Material 1 | Material 2 | μ_static (dry) | μ_static (lubricated) | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber | Concrete | 0.9-1.0 | N/A | Drive wheels, outdoor robots |

| Rubber | Wood | 0.5-0.7 | N/A | Indoor robot wheels |

| Rubber | Plastic | 0.4-0.6 | N/A | Gripper pads on plastic objects |

| Rubber | Metal | 0.6-0.8 | N/A | Gripper pads on metal parts |

| Plastic (ABS) | Plastic (ABS) | 0.3-0.4 | 0.1-0.2 | 3D printed gears, bushings |

| Plastic (Nylon) | Plastic (Nylon) | 0.15-0.25 | 0.08-0.15 | Low-friction bushings |

| Steel | Steel | 0.7-0.8 | 0.1-0.15 | Metal gears, shafts |

| Steel | Bronze | 0.4-0.5 | 0.15-0.2 | Bushings, low-friction surfaces |

| Aluminum | Aluminum | 1.0-1.4 | 0.3-0.4 | Structural joints (high, often problematic) |

| Aluminum | Steel | 0.6-0.7 | 0.2-0.3 | Mixed material mechanisms |

| PTFE (Teflon) | Steel | 0.04-0.1 | 0.04-0.08 | Ultra-low-friction bearings |

| Wood | Wood | 0.4-0.6 | 0.2-0.3 | Chassis materials, joints |

| Metal | Concrete | 0.4-0.6 | N/A | Wheels on rough surfaces |

These values are approximate and vary with surface finish, contamination, temperature, and other factors. Always test your specific materials under actual operating conditions when performance is critical.

Selecting Materials for Specific Needs

For maximum traction (drive wheels, gripper pads):

- Choose high-μ pairings: rubber on concrete, silicone on most surfaces

- Softer materials generally provide higher friction

- Surface texture can enhance mechanical interlocking

For minimum friction (bearings, sliding guides):

- Choose low-μ pairings: PTFE on steel, nylon on nylon

- Harder, smoother materials generally provide lower friction

- Always use appropriate lubrication

For moderate friction with self-lubrication (gears, bushings):

- Bronze on steel provides good balance

- Certain plastics (PEEK, Delrin) work well with metals

- Some material pairs naturally produce wear particles that lubricate the interface

Avoid problematic pairings:

- Aluminum on aluminum has very high friction and tends to gall (cold weld)

- Similar soft metals often stick to each other

- Some plastics degrade when exposed to petroleum-based lubricants

Temperature Effects: How Heat Changes Friction

Friction generates heat, and heat affects friction behavior—creating feedback loops that can lead to thermal runaway in poorly designed systems. Understanding these thermal effects prevents failures and improves reliability.

Heat Generation from Friction

Whenever friction forces act while surfaces move relative to each other, mechanical energy converts to heat. The power dissipated equals:

Power = friction_force × velocity

For sliding friction with 10 N force at 0.5 m/s: Power = 10 N × 0.5 m/s = 5 watts

Five watts might not sound like much, but concentrated in a small bearing or gear mesh, it can raise temperatures significantly. A small gearbox might contain only 50 grams of material. Five watts heating 50 grams raises temperature at:

Temperature rise rate = power ÷ (mass × specific_heat)

For aluminum (specific heat ≈ 900 J/kg/°C): Rate = 5 W ÷ (0.050 kg × 900 J/kg/°C) = 0.11°C per second

Without cooling, this gearbox would heat at 6.6°C per minute—reaching dangerously high temperatures within 10-15 minutes of continuous operation.

Temperature-Dependent Friction Changes

As temperature rises, friction behavior changes in complex ways:

Lubricants thin: Oils and greases become less viscous at higher temperatures, flowing more easily. This can reduce lubrication effectiveness, potentially increasing friction despite the lower viscosity.

Materials expand: Thermal expansion can alter clearances in bearings and gear meshes. Tighter clearances increase friction; excessive clearances reduce efficiency.

Material properties change: Some plastics soften at elevated temperatures, increasing friction and wear. Rubber can become sticky or, at very high temperatures, begin to degrade.

Thermal runaway risk: If heat generation exceeds heat dissipation, temperature rises continuously. Higher temperature increases friction (in some cases), generating more heat, raising temperature further in a runaway cycle leading to failure.

Thermal Management Strategies

Prevent overheating through:

Adequate cooling: Ensure airflow around motors and gearboxes. Add ventilation holes or small fans for high-power robots. Metal chassis can act as heat sinks, conducting heat away from hot components.

Duty cycle management: Intermittent operation allows cooling between active periods. A motor that would overheat in 10 minutes of continuous use might run indefinitely at 50% duty cycle (on for 30 seconds, off for 30 seconds).

Temperature monitoring: Add thermistors or other temperature sensors to critical components. Implement software limits that reduce power when temperatures exceed safe thresholds.

Improved lubrication: High-quality synthetic lubricants maintain better performance across wider temperature ranges than conventional oils and greases.

Material selection: Choose materials with good thermal stability. Metal gears tolerate higher temperatures than plastic. High-temperature plastics (PEEK, Delrin) outperform ABS or PLA at elevated temperatures.

Practical Friction Management Techniques

Successful robot design requires actively managing friction throughout the system. These practical techniques help you increase friction where beneficial and reduce it where harmful.

Technique 1: Segregate Functions

Design so that high-traction and low-friction requirements don’t conflict. For example:

- Use soft rubber on drive wheels for traction, but hard plastic or metal for idler wheels that need to spin freely

- Employ high-friction gripper pads for object holding, but low-friction slides for the gripper mechanism itself

- Select rough-surfaced materials for walking robot feet (traction), smooth materials for leg joints (free movement)

Technique 2: Conditional Friction

Some mechanisms benefit from friction that changes based on conditions:

Ratchet mechanisms: Allow free motion in one direction while locking in the other. Useful for climbing mechanisms or one-way drives.

Clutches: Engage friction to transmit force or disengage to allow free motion. Protects motors from overload and allows multiple actuators to share power sources.

Brakes: Apply friction deliberately to stop motion or hold position without continuous motor power. Electromagnetic or spring-loaded brakes add functionality without constant energy drain.

Technique 3: Surface Treatment

Modify surface properties to adjust friction:

Increase friction:

- Roughen surfaces (sandpaper, knurling, texturing)

- Add high-friction coatings (rubber spray, grip tape, silicone)

- Create mechanical interlocks (treads, spikes, textures)

Decrease friction:

- Polish surfaces to reduce roughness

- Apply low-friction coatings (PTFE spray, dry lubricants)

- Use harder materials that resist microscopic deformation

Technique 4: Load Management

Friction scales with normal force, so managing how loads distribute across surfaces affects friction:

For high traction:

- Design to maximize normal force on drive wheels (weight bias, downforce)

- Use suspension geometry that loads driven wheels during acceleration

- Add weight specifically over traction-critical points

For low friction:

- Minimize normal forces on bearings and sliding surfaces

- Use larger diameter shafts to reduce bearing loads for the same strength

- Support long spans with multiple bearings to distribute loads

Technique 5: Testing and Measurement

Empirically measure friction in your robot to verify calculations and identify problems:

Traction testing: Place your robot on different surfaces and measure maximum slope angle before wheels slip. This reveals actual traction coefficients:

μ_actual = tan(slip_angle)

If wheels slip at 40 degrees: μ_actual = tan(40°) ≈ 0.84

Coast-down testing: Accelerate your robot to a known speed, then coast without power while measuring deceleration. This reveals total friction:

Total friction force = mass × deceleration

If your 2 kg robot decelerates at 0.3 m/s²: Friction force = 2 kg × 0.3 m/s² = 0.6 N

Power consumption analysis: Measure battery current during various operations. Higher current than predicted suggests excessive friction somewhere in the drivetrain.

Temperature monitoring: Feel motors, gearboxes, and bearings after operation. Unusually hot components indicate excessive friction needing investigation.

Common Friction Problems and Solutions

Recognizing friction-related problems and knowing how to solve them helps you troubleshoot robots effectively.

Problem 1: Wheels Slipping During Acceleration

Symptoms: Wheels spin without gripping surface; robot accelerates poorly or not at all; squealing or chirping sounds from wheels.

Root Causes:

- Insufficient friction between wheels and surface

- Too much motor torque for available traction

- Poor weight distribution (too little weight on drive wheels)

- Worn or contaminated wheel surfaces

Solutions:

- Increase wheel friction: Replace wheels with softer rubber or add rubber coating to existing wheels

- Reduce motor torque: Lower maximum PWM in software or increase gear ratio (trading speed for torque)

- Improve weight distribution: Move battery or other heavy components toward drive wheels

- Clean surfaces: Remove oil, dust, or other contamination from wheels and floor

- Add traction control: Implement software that detects wheel slip (encoder speed exceeding expected) and reduces power

Problem 2: Robot Moves Sluggishly Despite Powerful Motors

Symptoms: Robot slower than expected; battery drains quickly; motors warm or hot after brief operation; difficulty climbing minor obstacles.

Root Causes:

- Excessive friction in drivetrain (bearings, gears, axles)

- Misaligned wheels or axles causing binding

- Over-tightened fasteners creating friction

- Inadequate or dried-out lubrication

Solutions:

- Check alignment: Ensure all wheels rotate freely when robot is lifted; verify axles are parallel

- Lubricate moving parts: Apply appropriate lubricant to gears, bearings, and axles

- Loosen over-tight fasteners: Tighten just enough to prevent loosening, not beyond

- Upgrade bearings: Replace plain bushings with ball bearings where friction is critical

- Verify clearances: Ensure adequate gaps in sliding mechanisms; parts shouldn’t bind

Problem 3: Gripper Drops Objects

Symptoms: Gripper successfully closes on object but cannot lift it; object slips from gripper during transport; needs excessive grip force.

Root Causes:

- Insufficient friction between gripper pads and object

- Gripper force too low for object weight

- Object surface too smooth or contaminated

- Poor gripper geometry (contact points not aligned with load)

Solutions:

- Add friction material: Apply rubber, silicone, or foam to gripper contact surfaces

- Increase grip force: Use stronger actuator or higher gear ratio on gripper motor

- Clean surfaces: Remove oil, powder coatings, or contaminants from object and gripper

- Improve geometry: Adjust gripper so contact points align with vertical load path

- Add more contact points: Use three-jaw or encompassing gripper instead of two-jaw design

Problem 4: Gears Stripping or Wearing Rapidly

Symptoms: Gear teeth show wear patterns, polish, or damage; plastic gears develop flat spots; metal gears show pitting; gears eventually strip completely under load.

Root Causes:

- Excessive friction from poor lubrication

- Misalignment causing uneven tooth contact

- Overloading gears beyond their capacity

- Incompatible materials (hard against soft)

Solutions:

- Proper lubrication: Apply appropriate grease or oil to gear teeth

- Fix alignment: Ensure gear shafts are properly positioned and parallel

- Reduce loads: Use larger/stronger gears or higher gear ratios to reduce torque per gear

- Material upgrade: Replace plastic gears with metal for high-load applications

- Check mesh depth: Adjust gear spacing for proper engagement (not too tight, not too loose)

Problem 5: High-Speed Vibration and Noise

Symptoms: Vibration or resonance at certain speeds; loud operation; reduced efficiency; gradual loosening of fasteners.

Root Causes:

- Stick-slip friction (alternating static and kinetic friction)

- Imbalanced rotating components

- Resonance frequencies matched to operating speeds

- Inadequate lubrication causing chattering

Solutions:

- Improve lubrication: Reduce stick-slip tendency with proper lubricants

- Balance components: Ensure wheels and rotating parts are balanced

- Change operating speed: Avoid resonance frequencies where vibration peaks

- Add damping: Use rubber isolation mounts or damping materials

- Increase stiffness: Stiffen structure to raise resonance frequencies above operating range

Advanced Friction Concepts

For sophisticated robots or special applications, several advanced friction-related concepts become relevant.

Stick-Slip Phenomenon

At very low speeds, some systems experience stick-slip oscillation—alternating between static friction (stuck) and kinetic friction (slipping). The system sticks until force builds enough to overcome static friction, then suddenly slips until velocity drops enough that static friction re-engages, then sticks again. This creates jerky motion and vibration.

Stick-slip commonly occurs in:

- Precise positioning systems at low speeds

- High-friction sliding mechanisms

- Under-lubricated surfaces

Solutions include:

- Better lubrication to reduce friction difference between static and kinetic

- Increased velocity to operate in kinetic regime continuously

- Stiffer mechanical coupling to reduce compliance that enables oscillation

- Dithering (adding small high-frequency vibrations to keep system in kinetic regime)

Coulomb Versus Viscous Friction Models

Simple friction models assume constant friction (Coulomb friction), but real systems often combine Coulomb and viscous friction:

F_total = F_coulomb + b × v

Where the constant Coulomb term represents dry friction and the velocity-dependent term represents viscous effects from lubricants or air resistance.

For accurate control of precision robots, you may need to characterize both components and compensate for them in your control algorithms. This is especially important for robot arms requiring smooth motion across wide speed ranges.

Friction in Control Systems

Friction affects control system performance in several ways:

Steady-state error: In position control, friction creates a dead zone where small errors don’t generate enough force to overcome static friction. The system settles close to the target but not exactly on it.

Limit cycles: Friction can cause oscillation in control systems. The controller tries to correct position error, overcomes friction and moves too far, tries to correct back, and oscillates around the setpoint.

Nonlinear behavior: Friction’s dependence on velocity direction (always opposing motion) creates nonlinearity that simple linear control algorithms may handle poorly.

Advanced control techniques for friction compensation include:

- Feedforward compensation (adding extra control effort to overcome predicted friction)

- Dead zone compensation (using larger control signals near zero velocity)

- Adaptive control (continuously estimating and compensating for changing friction)

Friction Testing and Measurement

Accurately measuring friction coefficients and forces helps you design robots based on data rather than assumptions.

Measuring Friction Coefficients

To measure μ between two materials:

Incline method:

- Create an inclined plane from one material

- Place a block of the other material on it

- Gradually increase incline angle until block just begins sliding

- Measure the angle at sliding onset

- Calculate: μ = tan(angle)

Pull test method:

- Place a known weight of one material on a horizontal surface of the other material

- Attach a force gauge and pull horizontally

- Record force needed to initiate motion (static friction)

- Record force needed to maintain constant slow motion (kinetic friction)

- Calculate: μ_static = F_static / weight, μ_kinetic = F_kinetic / weight

Measuring Rolling Resistance

For wheels on different surfaces:

Coast-down test:

- Accelerate robot to known speed

- Cut power and measure distance until stopped

- Calculate deceleration: a = v² / (2 × distance)

- Calculate rolling resistance: F_rr = mass × deceleration

- Calculate C_rr = F_rr / weight

Constant speed test:

- Measure power/current needed to maintain constant speed on level surface

- Power goes into rolling resistance and air resistance (usually negligible at low speeds)

- Calculate rolling friction force from power and speed

- Calculate C_rr from force and weight

Measuring Bearing and Gear Friction

For internal mechanism friction:

No-load speed test:

- Run motor with no load, measure speed

- Run motor with mechanism attached, measure new speed

- Speed reduction indicates friction loading

- Estimate friction torque from motor performance curve

Current measurement:

- Measure current at no load

- Measure current with mechanism engaged

- Current increase indicates friction power

- Calculate friction torque from power and speed

Friction in Specific Robot Types

Different robot architectures face unique friction challenges requiring tailored solutions.

Mobile Wheeled Robots

Primary friction concerns:

- Adequate drive wheel traction

- Minimized rolling resistance for efficiency

- Low-friction steering mechanisms (for Ackermann or differential steering)

Typical solutions:

- Soft rubber drive wheels for traction

- Hard plastic or metal idler wheels for efficiency

- Ball bearings on all rotating axles

- Proper lubrication of steering pivots

Legged Walking Robots

Primary friction concerns:

- High friction between feet and ground (prevent slipping)

- Low friction in leg joints (allow free movement)

- Managing friction during stance and swing phases

Typical solutions:

- Rubber or textured feet for ground traction

- Ball bearings or low-friction bushings in joints

- Compliant elements in legs to maintain ground contact

- Sufficient servo torque to overcome joint friction

Robot Arms and Manipulators

Primary friction concerns:

- Low joint friction for smooth motion

- High gripper friction for secure grasping

- Precise friction compensation for accurate positioning

Typical solutions:

- High-quality bearings in all joints

- Friction compensation in control software

- Soft, compliant gripper pads

- Regular lubrication maintenance

Underwater Robots

Primary friction concerns:

- Viscous drag dominates (not dry friction)

- Sealed bearing friction (waterproof bearings have higher friction)

- Biofouling increasing friction over time

Typical solutions:

- Streamlined hydrodynamic shapes

- Specialized waterproof bearings (accept higher friction)

- Powerful thrusters to overcome drag

- Anti-fouling coatings on external surfaces

Comparison Table: Friction Management Strategies

| Strategy | Friction Change | Implementation Cost | Maintenance | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material Selection | ±50-300% | Low to Medium | None | All applications, permanent solution | Limited to available materials |

| Surface Treatment | ±30-150% | Low | Periodic reapplication | Targeted improvements | May wear off over time |

| Lubrication | -30-80% | Very Low | Regular reapplication | Reducing friction, extending life | Attracts contamination, temperature limits |

| Bearing Upgrade | -80-95% | Medium | Minimal | High-speed, high-load applications | Cost, space requirements |

| Geometry Optimization | ±20-60% | Medium to High | None | Custom designs | Requires design effort, may affect other parameters |

| Load Management | ±20-100% | Low to Medium | None | Adjusting specific contact forces | May conflict with other requirements |

| Active Control | Variable | High | Software tuning | Dynamic conditions, precision | Complexity, requires sensors |

Conclusion: Mastering the Friction Paradox

Friction represents one of robotics’ most interesting paradoxes—you simultaneously need it and need to eliminate it, often in the same robot and sometimes even in the same mechanism. Success comes not from treating friction as simply good or bad but from understanding its nuanced role in each part of your system and engineering appropriately.

The skills you develop around friction management—calculating required traction, measuring actual friction coefficients, selecting appropriate materials, applying lubrication correctly, diagnosing friction-related problems—transfer across all robotics domains. Whether you’re building a simple line-follower or a sophisticated mobile manipulator, friction considerations influence design decisions at every level.

Start by identifying where friction matters most in your specific robot. For a mobile robot, wheel traction probably deserves the most attention. For a robot arm, joint friction and gripper friction are likely critical. For a high-speed competition robot, drivetrain efficiency might dominate. Prioritize your efforts where they’ll have the most impact rather than trying to optimize everything simultaneously.

Measure and test rather than assuming. That rubber compound you think provides excellent traction might actually have a lower coefficient than you expected on your particular surface. That gearbox you assumed was efficient might waste substantial power due to misalignment or inadequate lubrication. Simple tests reveal actual performance and guide improvements.

Accept that friction management involves trade-offs. Adding softer rubber to drive wheels improves traction but increases rolling resistance and reduces efficiency. Using ball bearings everywhere improves efficiency but costs more and takes more space than simple bushings. Adding grease reduces friction but attracts dust and dirt. Making informed trade-offs based on your robot’s specific requirements separates good designs from poor ones.

Document what works and what doesn’t. When you find a wheel material that provides excellent traction on your test surface, record it for future projects. When you discover a lubricant that performs well in your climate, note it. When you solve a friction-related problem, document the solution. This builds personal knowledge that accelerates each successive project.

Remember that friction isn’t static—it changes with temperature, wear, contamination, and other factors. Designs that work perfectly when new might develop problems after hours of operation as lubricants distribute, surfaces wear, or dirt accumulates. Build in maintenance procedures and monitor performance over time rather than assuming initial performance persists indefinitely.

Most importantly, develop intuition through hands-on experience. Reading about friction coefficients is valuable, but nothing replaces actually feeling the difference between a high-friction and low-friction bearing, or observing how different wheel materials behave on various surfaces. Build small test mechanisms to experiment with friction effects. Try different lubricants and materials. Learn through direct experience what works and what doesn’t.

Friction will remain both friend and enemy throughout your robotics journey. Master it not by eliminating it completely—impossible and undesirable—but by understanding it thoroughly and manipulating it deliberately. Design systems where friction helps you (traction, gripping) and minimal where it hurts you (bearings, gears). This deliberate, informed approach to friction management transforms adequate robots into excellent ones, turning the friction paradox from an obstacle into a tool you wield with confidence and precision.