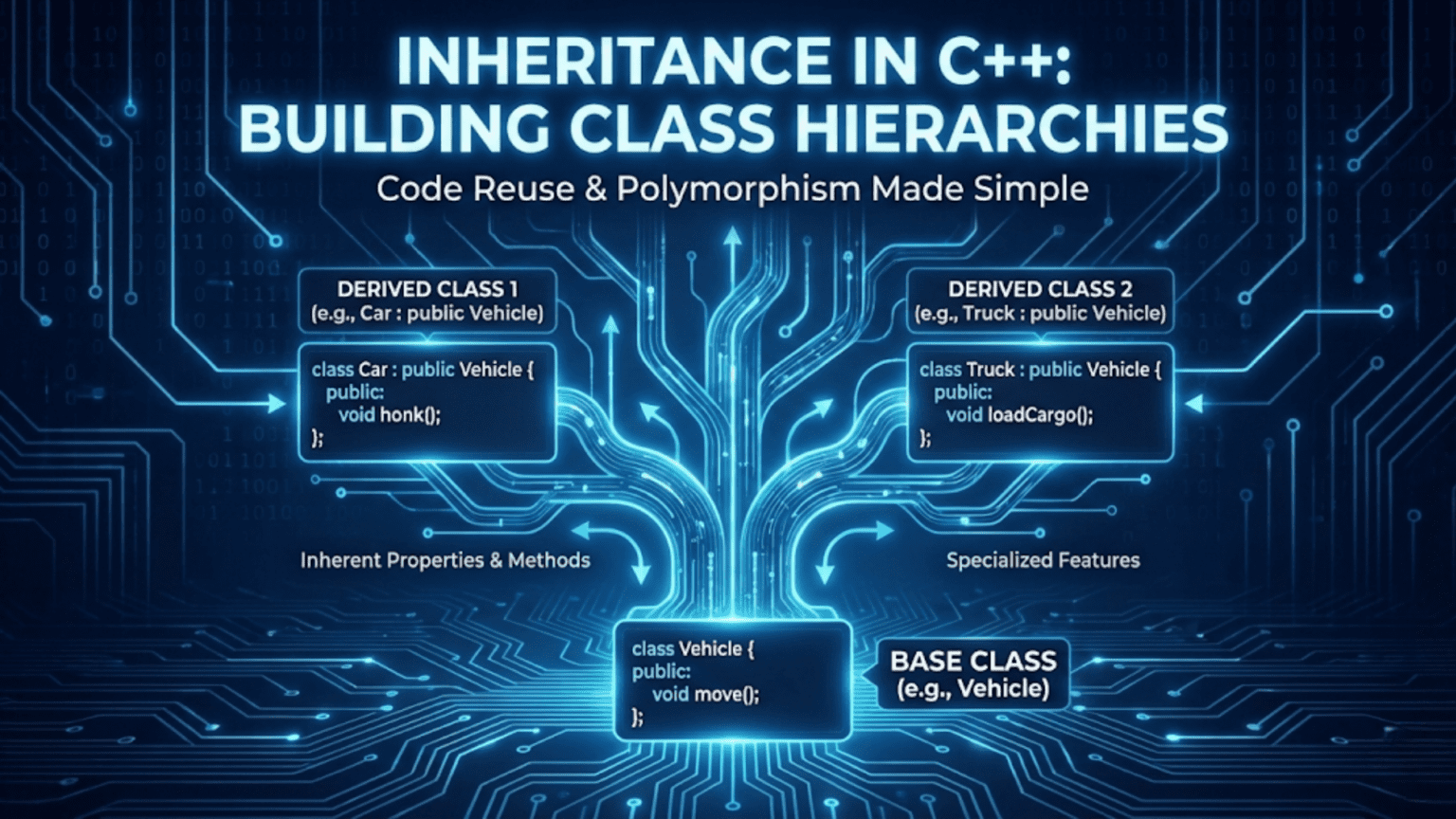

Inheritance in C++ is an object-oriented programming mechanism that allows a new class (derived class) to acquire properties and behaviors from an existing class (base class), enabling code reuse, establishing hierarchical relationships, and creating extensible software architectures. This fundamental concept promotes the “is-a” relationship between classes and reduces code duplication through shared functionality.

Introduction: The Foundation of Object-Oriented Design

Inheritance stands as one of the most powerful features in C++ and object-oriented programming as a whole. It enables you to build upon existing code, creating new classes that extend and specialize the functionality of existing ones without rewriting everything from scratch. This isn’t just about convenience—it’s about creating logical, maintainable software architectures that mirror real-world relationships.

Consider the natural world: a dog is an animal, a car is a vehicle, a savings account is a bank account. These “is-a” relationships form the conceptual foundation of inheritance. In C++, you can model these relationships directly in code, creating base classes that define common characteristics and derived classes that add specific features.

When you master inheritance, you unlock the ability to create sophisticated software systems where changes in common functionality automatically propagate to all related classes, where new features can be added without disrupting existing code, and where your codebase becomes a well-organized hierarchy of related concepts rather than a collection of disconnected pieces.

This comprehensive guide will take you from the basics of single inheritance through advanced topics like multiple inheritance, virtual functions, and abstract classes. You’ll learn not just the syntax, but the design principles that make inheritance a cornerstone of professional C++ development.

What is Inheritance? Understanding the Core Concept

Inheritance is the mechanism by which one class (the derived class or child class) inherits properties and methods from another class (the base class or parent class). The derived class automatically receives all the members of the base class and can add its own unique members or modify inherited behavior.

Think of inheritance like a family tree or an organizational chart. Just as a manager inherits general employee attributes but has additional responsibilities, a derived class inherits base class features while adding specialized capabilities.

The Benefits of Inheritance

Code Reusability: Write common functionality once in a base class, then reuse it in multiple derived classes. If you have ten types of vehicles, you don’t write the “start engine” code ten times—you write it once in the Vehicle base class.

Logical Organization: Inheritance creates intuitive hierarchies that mirror real-world relationships. Your code structure becomes self-documenting, making it easier for others (and future you) to understand.

Extensibility: Add new functionality by creating new derived classes without modifying existing code. This adheres to the Open/Closed Principle: software should be open for extension but closed for modification.

Polymorphism: Inheritance enables polymorphism, allowing you to write code that works with base class pointers but executes derived class behavior—a powerful technique we’ll explore in depth.

Maintenance: Fix a bug or improve a method in the base class, and all derived classes automatically benefit from the improvement.

Basic Inheritance Syntax: Creating Your First Hierarchy

The fundamental syntax for inheritance in C++ uses a colon followed by an access specifier and the base class name:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// Base class - defines common properties

class Animal {

protected:

string name;

int age;

public:

Animal(string n, int a) : name(n), age(a) {

cout << "Animal constructor called" << endl;

}

void eat() {

cout << name << " is eating." << endl;

}

void sleep() {

cout << name << " is sleeping." << endl;

}

void displayInfo() {

cout << "Name: " << name << endl;

cout << "Age: " << age << " years" << endl;

}

};

// Derived class - inherits from Animal and adds specific features

class Dog : public Animal {

private:

string breed;

public:

Dog(string n, int a, string b) : Animal(n, a), breed(b) {

cout << "Dog constructor called" << endl;

}

void bark() {

cout << name << " says: Woof! Woof!" << endl;

}

void displayBreed() {

cout << "Breed: " << breed << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Dog myDog("Buddy", 3, "Golden Retriever");

// Can use inherited methods

myDog.eat();

myDog.sleep();

myDog.displayInfo();

// Can use Dog-specific methods

myDog.bark();

myDog.displayBreed();

return 0;

}Output:

Animal constructor called

Dog constructor called

Buddy is eating.

Buddy is sleeping.

Name: Buddy

Age: 3 years

Woof! Woof!

Breed: Golden RetrieverNotice how the Dog class automatically has access to eat(), sleep(), and displayInfo() methods without defining them. The Dog object is both a Dog and an Animal—it inherits all Animal capabilities while adding its own.

Types of Inheritance Access Specifiers

When you inherit from a base class, you specify the access level using public, protected, or private inheritance. This determines how the inherited members are accessible in the derived class.

Public Inheritance (Most Common)

Public inheritance maintains the access levels of base class members in the derived class. This is the most common and intuitive form of inheritance, representing a true “is-a” relationship.

class Vehicle {

protected:

string brand;

int year;

public:

Vehicle(string b, int y) : brand(b), year(y) {}

void displayBrand() {

cout << "Brand: " << brand << endl;

}

};

// Public inheritance - Car IS-A Vehicle

class Car : public Vehicle {

private:

int numDoors;

public:

Car(string b, int y, int doors) : Vehicle(b, y), numDoors(doors) {}

void displayCarInfo() {

displayBrand(); // public method remains public

cout << "Year: " << year << endl; // protected member accessible

cout << "Doors: " << numDoors << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Car myCar("Toyota", 2024, 4);

myCar.displayBrand(); // Can call public inherited method

myCar.displayCarInfo();

}Protected Inheritance

Protected inheritance makes all public and protected members of the base class protected in the derived class. This is less common but useful when you want to hide the base class interface from external code while allowing further derived classes to access it.

class Engine {

public:

void start() {

cout << "Engine starting..." << endl;

}

void stop() {

cout << "Engine stopping..." << endl;

}

};

// Protected inheritance

class Car : protected Engine {

public:

void drive() {

start(); // Can use Engine methods internally

cout << "Car is driving" << endl;

}

void park() {

cout << "Car is parking" << endl;

stop(); // Can use Engine methods internally

}

};

int main() {

Car myCar;

myCar.drive();

myCar.park();

// myCar.start(); // Error! start() is protected in Car

}Private Inheritance

Private inheritance makes all base class members private in the derived class, effectively hiding them from both external code and further derived classes. This represents a “implemented-in-terms-of” relationship rather than “is-a.”

class Timer {

public:

void start() {

cout << "Timer started" << endl;

}

void stop() {

cout << "Timer stopped" << endl;

}

};

// Private inheritance - implementation detail, not IS-A

class Benchmark : private Timer {

public:

void runBenchmark() {

start(); // Use Timer internally

cout << "Running performance test..." << endl;

stop();

}

};

int main() {

Benchmark test;

test.runBenchmark();

// test.start(); // Error! Timer methods are private in Benchmark

}Inheritance Access Control Table

| Base Class Member | Public Inheritance | Protected Inheritance | Private Inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|

| public | public | protected | private |

| protected | protected | protected | private |

| private | not accessible | not accessible | not accessible |

Constructors and Destructors in Inheritance

Understanding how constructors and destructors work in inheritance hierarchies is crucial for proper resource management and object initialization.

Constructor Calling Order

When you create a derived class object, constructors are called in a specific order: base class constructor first, then derived class constructor. This makes sense—you need to build the foundation before adding specialized features.

class Base {

public:

Base() {

cout << "1. Base constructor called" << endl;

}

Base(int x) {

cout << "1. Base constructor with parameter: " << x << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

Derived() {

cout << "2. Derived constructor called" << endl;

}

Derived(int x) : Base(x) { // Explicitly call base constructor

cout << "2. Derived constructor called" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "Creating object without parameters:" << endl;

Derived obj1;

cout << "\nCreating object with parameters:" << endl;

Derived obj2(42);

}Output:

Creating object without parameters:

1. Base constructor called

2. Derived constructor called

Creating object with parameters:

1. Base constructor with parameter: 42

2. Derived constructor calledDestructor Calling Order

Destructors are called in reverse order: derived class destructor first, then base class destructor. This ensures proper cleanup—specialized resources are released before general ones.

class Base {

public:

Base() {

cout << "Base constructor" << endl;

}

~Base() {

cout << "Base destructor" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

Derived() {

cout << "Derived constructor" << endl;

}

~Derived() {

cout << "Derived destructor" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "Creating object:" << endl;

Derived obj;

cout << "\nObject going out of scope:" << endl;

// Destructors called automatically

}Output:

Creating object:

Base constructor

Derived constructor

Object going out of scope:

Derived destructor

Base destructorPassing Parameters to Base Class Constructors

You must explicitly pass parameters to base class constructors using the member initializer list:

class Person {

protected:

string name;

int age;

public:

Person(string n, int a) : name(n), age(a) {

cout << "Person created: " << name << endl;

}

};

class Student : public Person {

private:

string studentId;

double gpa;

public:

// Must call Person constructor with required parameters

Student(string n, int a, string id, double g)

: Person(n, a), studentId(id), gpa(g) {

cout << "Student enrolled: " << studentId << endl;

}

void displayInfo() {

cout << "Name: " << name << endl;

cout << "Age: " << age << endl;

cout << "ID: " << studentId << endl;

cout << "GPA: " << gpa << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Student student("Alice Johnson", 20, "S12345", 3.8);

student.displayInfo();

}Method Overriding: Customizing Inherited Behavior

Derived classes can override base class methods to provide specialized implementations. This is fundamental to polymorphism and allows derived classes to customize inherited behavior.

class Shape {

protected:

string color;

public:

Shape(string c) : color(c) {}

// Virtual function can be overridden

virtual void draw() {

cout << "Drawing a generic shape in " << color << endl;

}

virtual double getArea() {

return 0.0;

}

void displayColor() {

cout << "Color: " << color << endl;

}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(string c, double r) : Shape(c), radius(r) {}

// Override the draw method

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a circle with radius " << radius

<< " in " << color << endl;

}

// Override the getArea method

double getArea() override {

return 3.14159 * radius * radius;

}

};

class Rectangle : public Shape {

private:

double width;

double height;

public:

Rectangle(string c, double w, double h)

: Shape(c), width(w), height(h) {}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a rectangle " << width << "x" << height

<< " in " << color << endl;

}

double getArea() override {

return width * height;

}

};

int main() {

Circle circle("red", 5.0);

Rectangle rect("blue", 4.0, 6.0);

circle.draw();

cout << "Circle area: " << circle.getArea() << endl;

rect.draw();

cout << "Rectangle area: " << rect.getArea() << endl;

}Output:

Drawing a circle with radius 5 in red

Circle area: 78.5397

Drawing a rectangle 4x6 in blue

Rectangle area: 24The override keyword (C++11) is optional but highly recommended—it tells the compiler you intend to override a base class method, catching errors if the method signature doesn’t match.

Multi-Level Inheritance: Building Deeper Hierarchies

Multi-level inheritance creates chains of inheritance where a class inherits from a derived class, creating a grandfather-father-son relationship.

class LivingBeing {

protected:

bool isAlive;

public:

LivingBeing() : isAlive(true) {

cout << "LivingBeing constructor" << endl;

}

void breathe() {

cout << "Breathing..." << endl;

}

};

class Animal : public LivingBeing {

protected:

int legs;

public:

Animal(int l) : legs(l) {

cout << "Animal constructor" << endl;

}

void move() {

cout << "Moving with " << legs << " legs" << endl;

}

};

class Dog : public Animal {

private:

string breed;

public:

Dog(string b) : Animal(4), breed(b) {

cout << "Dog constructor" << endl;

}

void bark() {

cout << breed << " is barking!" << endl;

}

void displayAll() {

breathe(); // From LivingBeing

move(); // From Animal

bark(); // From Dog

}

};

int main() {

Dog myDog("Labrador");

cout << "\nDog capabilities:" << endl;

myDog.displayAll();

}Output:

LivingBeing constructor

Animal constructor

Dog constructor

Dog capabilities:

Breathing...

Moving with 4 legs

Labrador is barking!Multiple Inheritance: Inheriting from Multiple Base Classes

C++ supports multiple inheritance, where a class can inherit from more than one base class. This is powerful but must be used carefully to avoid complexity and the diamond problem.

class Flyer {

protected:

double maxAltitude;

public:

Flyer(double altitude) : maxAltitude(altitude) {}

void fly() {

cout << "Flying at max altitude: " << maxAltitude << " feet" << endl;

}

};

class Swimmer {

protected:

double maxDepth;

public:

Swimmer(double depth) : maxDepth(depth) {}

void swim() {

cout << "Swimming at max depth: " << maxDepth << " feet" << endl;

}

};

// Multiple inheritance - Duck can both fly and swim

class Duck : public Flyer, public Swimmer {

private:

string name;

public:

Duck(string n, double altitude, double depth)

: Flyer(altitude), Swimmer(depth), name(n) {

cout << "Duck " << name << " created" << endl;

}

void quack() {

cout << name << " says: Quack!" << endl;

}

void showCapabilities() {

cout << "\n" << name << "'s capabilities:" << endl;

fly();

swim();

quack();

}

};

int main() {

Duck mallard("Donald", 5000.0, 10.0);

mallard.showCapabilities();

}Output:

Duck Donald created

Donald's capabilities:

Flying at max altitude: 5000 feet

Swimming at max depth: 10 feet

Donald says: Quack!The Diamond Problem and Virtual Inheritance

The diamond problem occurs when a class inherits from two classes that share a common base class, creating ambiguity. Virtual inheritance solves this:

class Device {

protected:

string deviceId;

public:

Device(string id) : deviceId(id) {

cout << "Device constructor: " << deviceId << endl;

}

void powerOn() {

cout << "Device " << deviceId << " powered on" << endl;

}

};

// Virtual inheritance prevents duplicate Device instances

class Scanner : virtual public Device {

public:

Scanner(string id) : Device(id) {

cout << "Scanner constructor" << endl;

}

void scan() {

cout << "Scanning document..." << endl;

}

};

class Printer : virtual public Device {

public:

Printer(string id) : Device(id) {

cout << "Printer constructor" << endl;

}

void print() {

cout << "Printing document..." << endl;

}

};

class MultiFunctionDevice : public Scanner, public Printer {

public:

MultiFunctionDevice(string id)

: Device(id), Scanner(id), Printer(id) {

cout << "MultiFunctionDevice constructor" << endl;

}

void copyDocument() {

scan();

print();

}

};

int main() {

MultiFunctionDevice mfd("MFD-001");

cout << "\nUsing device:" << endl;

mfd.powerOn(); // No ambiguity - only one Device base

mfd.copyDocument();

}Polymorphism Through Inheritance

Polymorphism allows you to treat derived class objects as base class objects, enabling flexible and extensible code.

class Employee {

protected:

string name;

int id;

double baseSalary;

public:

Employee(string n, int i, double salary)

: name(n), id(i), baseSalary(salary) {}

// Virtual function for polymorphic behavior

virtual double calculatePay() {

return baseSalary;

}

virtual void displayInfo() {

cout << "Employee: " << name << " (ID: " << id << ")" << endl;

cout << "Pay: $" << calculatePay() << endl;

}

virtual ~Employee() {} // Virtual destructor important for polymorphism

};

class Manager : public Employee {

private:

double bonus;

public:

Manager(string n, int i, double salary, double b)

: Employee(n, i, salary), bonus(b) {}

double calculatePay() override {

return baseSalary + bonus;

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "Manager: " << name << " (ID: " << id << ")" << endl;

cout << "Base Salary: $" << baseSalary << endl;

cout << "Bonus: $" << bonus << endl;

cout << "Total Pay: $" << calculatePay() << endl;

}

};

class Developer : public Employee {

private:

int projectsCompleted;

double projectBonus;

public:

Developer(string n, int i, double salary, int projects)

: Employee(n, i, salary), projectsCompleted(projects),

projectBonus(500.0) {}

double calculatePay() override {

return baseSalary + (projectsCompleted * projectBonus);

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "Developer: " << name << " (ID: " << id << ")" << endl;

cout << "Projects Completed: " << projectsCompleted << endl;

cout << "Total Pay: $" << calculatePay() << endl;

}

};

void processPayroll(Employee* employees[], int count) {

double totalPayroll = 0;

cout << "=== Payroll Processing ===" << endl;

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

employees[i]->displayInfo();

totalPayroll += employees[i]->calculatePay();

cout << "---" << endl;

}

cout << "Total Payroll: $" << totalPayroll << endl;

}

int main() {

Employee* employees[3];

employees[0] = new Employee("John Smith", 101, 50000);

employees[1] = new Manager("Sarah Johnson", 102, 70000, 15000);

employees[2] = new Developer("Mike Chen", 103, 65000, 8);

processPayroll(employees, 3);

// Clean up

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

delete employees[i];

}

return 0;

}This demonstrates polymorphism’s power: the processPayroll function works with Employee pointers but correctly calls the appropriate calculatePay() and displayInfo() methods for each actual object type.

Abstract Classes and Pure Virtual Functions

Abstract classes define interfaces that derived classes must implement. They cannot be instantiated and typically contain pure virtual functions.

class Shape {

protected:

string color;

public:

Shape(string c) : color(c) {}

// Pure virtual functions - must be overridden

virtual double getArea() = 0;

virtual double getPerimeter() = 0;

virtual void draw() = 0;

// Regular virtual function - can be overridden

virtual void displayColor() {

cout << "Color: " << color << endl;

}

virtual ~Shape() {}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(string c, double r) : Shape(c), radius(r) {}

double getArea() override {

return 3.14159 * radius * radius;

}

double getPerimeter() override {

return 2 * 3.14159 * radius;

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a " << color << " circle" << endl;

}

};

class Triangle : public Shape {

private:

double side1, side2, side3;

public:

Triangle(string c, double s1, double s2, double s3)

: Shape(c), side1(s1), side2(s2), side3(s3) {}

double getArea() override {

// Heron's formula

double s = (side1 + side2 + side3) / 2;

return sqrt(s * (s - side1) * (s - side2) * (s - side3));

}

double getPerimeter() override {

return side1 + side2 + side3;

}

void draw() override {

cout << "Drawing a " << color << " triangle" << endl;

}

};

void analyzeShape(Shape* shape) {

shape->draw();

shape->displayColor();

cout << "Area: " << shape->getArea() << endl;

cout << "Perimeter: " << shape->getPerimeter() << endl;

cout << endl;

}

int main() {

// Shape shape("red"); // Error! Cannot instantiate abstract class

Shape* shapes[2];

shapes[0] = new Circle("red", 5.0);

shapes[1] = new Triangle("blue", 3.0, 4.0, 5.0);

for (int i = 0; i < 2; i++) {

analyzeShape(shapes[i]);

delete shapes[i];

}

return 0;

}Protected Members: The Inheritance Sweet Spot

Protected members strike a balance between encapsulation and inheritance flexibility. They’re accessible in derived classes but hidden from external code.

class BankAccount {

protected:

double balance;

string accountNumber;

// Protected helper method for derived classes

void logTransaction(string transaction) {

cout << "[" << accountNumber << "] " << transaction << endl;

}

private:

string pin; // Truly private - not even derived classes can access

public:

BankAccount(string accNum, double initialBalance, string p)

: accountNumber(accNum), balance(initialBalance), pin(p) {}

virtual void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount;

logTransaction("Deposited $" + to_string(amount));

}

}

double getBalance() const {

return balance;

}

};

class SavingsAccount : public BankAccount {

private:

double interestRate;

public:

SavingsAccount(string accNum, double initialBalance, string p, double rate)

: BankAccount(accNum, initialBalance, p), interestRate(rate) {}

void applyInterest() {

// Can access protected balance and logTransaction

double interest = balance * interestRate;

balance += interest;

logTransaction("Interest applied: $" + to_string(interest));

}

void deposit(double amount) override {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount; // Can access protected balance

// Apply bonus for large deposits

if (amount >= 1000) {

double bonus = amount * 0.01;

balance += bonus;

logTransaction("Deposit bonus: $" + to_string(bonus));

}

logTransaction("Deposited $" + to_string(amount));

}

}

};

int main() {

SavingsAccount savings("SAV-001", 1000.0, "1234", 0.05);

cout << "Initial balance: $" << savings.getBalance() << endl;

savings.deposit(1500);

savings.applyInterest();

cout << "Final balance: $" << savings.getBalance() << endl;

}Real-World Example: Building a Complete Hierarchy

Let’s create a comprehensive employee management system demonstrating multiple inheritance concepts:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

// Abstract base class

class Person {

protected:

string name;

int age;

string address;

public:

Person(string n, int a, string addr)

: name(n), age(a), address(addr) {}

virtual void displayInfo() = 0; // Pure virtual

string getName() const { return name; }

virtual ~Person() {}

};

// Employee base class

class Employee : public Person {

protected:

int employeeId;

string department;

double baseSalary;

public:

Employee(string n, int a, string addr, int id, string dept, double salary)

: Person(n, a, addr), employeeId(id), department(dept),

baseSalary(salary) {}

virtual double calculateSalary() {

return baseSalary;

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "Name: " << name << endl;

cout << "Employee ID: " << employeeId << endl;

cout << "Department: " << department << endl;

cout << "Salary: $" << calculateSalary() << endl;

}

int getEmployeeId() const { return employeeId; }

};

// Manager class - has leadership responsibilities

class Manager : public Employee {

private:

vector<int> teamMemberIds;

double managementBonus;

public:

Manager(string n, int a, string addr, int id, string dept,

double salary, double bonus)

: Employee(n, a, addr, id, dept, salary),

managementBonus(bonus) {}

void addTeamMember(int memberId) {

teamMemberIds.push_back(memberId);

}

double calculateSalary() override {

return baseSalary + managementBonus + (teamMemberIds.size() * 500);

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "=== MANAGER ===" << endl;

Employee::displayInfo(); // Call base class version

cout << "Team Size: " << teamMemberIds.size() << endl;

cout << "Management Bonus: $" << managementBonus << endl;

}

};

// Developer class - technical employee

class Developer : public Employee {

private:

string programmingLanguage;

int projectsCompleted;

public:

Developer(string n, int a, string addr, int id, string dept,

double salary, string lang)

: Employee(n, a, addr, id, dept, salary),

programmingLanguage(lang), projectsCompleted(0) {}

void completeProject() {

projectsCompleted++;

cout << name << " completed a project in "

<< programmingLanguage << endl;

}

double calculateSalary() override {

return baseSalary + (projectsCompleted * 1000);

}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "=== DEVELOPER ===" << endl;

Employee::displayInfo();

cout << "Programming Language: " << programmingLanguage << endl;

cout << "Projects Completed: " << projectsCompleted << endl;

}

};

// Intern class - temporary employee

class Intern : public Employee {

private:

string university;

int monthsRemaining;

public:

Intern(string n, int a, string addr, int id, string dept,

double salary, string uni, int months)

: Employee(n, a, addr, id, dept, salary),

university(uni), monthsRemaining(months) {}

void displayInfo() override {

cout << "=== INTERN ===" << endl;

Employee::displayInfo();

cout << "University: " << university << endl;

cout << "Months Remaining: " << monthsRemaining << endl;

}

void progressMonth() {

if (monthsRemaining > 0) {

monthsRemaining--;

}

}

};

// Company class to manage employees

class Company {

private:

string companyName;

vector<Employee*> employees;

public:

Company(string name) : companyName(name) {}

void hireEmployee(Employee* emp) {

employees.push_back(emp);

cout << emp->getName() << " hired!" << endl;

}

void displayAllEmployees() {

cout << "\n========== " << companyName << " Employees ==========" << endl;

for (Employee* emp : employees) {

emp->displayInfo();

cout << "---" << endl;

}

}

double calculateTotalPayroll() {

double total = 0;

for (Employee* emp : employees) {

total += emp->calculateSalary();

}

return total;

}

~Company() {

for (Employee* emp : employees) {

delete emp;

}

}

};

int main() {

Company techCorp("TechCorp Solutions");

// Hire different types of employees

Manager* mgr = new Manager("Sarah Williams", 35, "123 Main St",

1001, "Engineering", 90000, 15000);

Developer* dev1 = new Developer("John Smith", 28, "456 Oak Ave",

1002, "Engineering", 75000, "C++");

Developer* dev2 = new Developer("Emily Chen", 26, "789 Pine Rd",

1003, "Engineering", 72000, "Python");

Intern* intern = new Intern("Mike Johnson", 22, "321 Elm St",

1004, "Engineering", 35000, "MIT", 6);

techCorp.hireEmployee(mgr);

techCorp.hireEmployee(dev1);

techCorp.hireEmployee(dev2);

techCorp.hireEmployee(intern);

cout << "\n--- Setting up team ---" << endl;

mgr->addTeamMember(1002);

mgr->addTeamMember(1003);

mgr->addTeamMember(1004);

cout << "\n--- Developers working ---" << endl;

dev1->completeProject();

dev1->completeProject();

dev2->completeProject();

// Display all employees

techCorp.displayAllEmployees();

// Calculate payroll

cout << "\nTotal Company Payroll: $"

<< techCorp.calculateTotalPayroll() << endl;

return 0;

}Common Inheritance Mistakes and Solutions

Mistake 1: Forgetting to Call Base Constructor

// Bad - base class default constructor must exist

class Base {

public:

Base(int x) {

cout << "Base constructor: " << x << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

Derived() { // Error! No Base() constructor

cout << "Derived constructor" << endl;

}

};

// Good - explicitly call base constructor

class FixedDerived : public Base {

public:

FixedDerived() : Base(0) { // Provide required parameter

cout << "Derived constructor" << endl;

}

};Mistake 2: Hiding Base Class Methods Unintentionally

class Base {

public:

void display() {

cout << "Base display" << endl;

}

void display(int x) {

cout << "Base display with int: " << x << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

void display() { // Hides ALL base class display methods

cout << "Derived display" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Derived d;

d.display(); // OK - calls Derived::display()

// d.display(5); // Error! Base::display(int) is hidden

// Solution: use 'using' declaration

class FixedDerived : public Base {

public:

using Base::display; // Make base versions visible

void display() {

cout << "FixedDerived display" << endl;

}

};

FixedDerived fd;

fd.display(); // Calls FixedDerived::display()

fd.display(5); // Calls Base::display(int) - now accessible!

}Mistake 3: Slicing Objects

class Base {

public:

int baseValue;

Base() : baseValue(1) {}

virtual void show() {

cout << "Base: " << baseValue << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

int derivedValue;

Derived() : derivedValue(2) {}

void show() override {

cout << "Derived: " << baseValue << ", " << derivedValue << endl;

}

};

void badFunction(Base obj) { // Takes by value - slicing occurs!

obj.show();

}

void goodFunction(Base& obj) { // Takes by reference - no slicing

obj.show();

}

int main() {

Derived d;

badFunction(d); // Slicing! Copies only Base part

goodFunction(d); // No slicing - polymorphism works

}Best Practices for Inheritance

1. Prefer Composition Over Inheritance When Appropriate

Inheritance represents “is-a” relationships. If the relationship is “has-a,” use composition instead:

// Bad - Car is not an Engine

class Car : public Engine {

// ...

};

// Good - Car has an Engine

class Car {

private:

Engine engine;

// ...

};2. Make Base Class Destructors Virtual

When using polymorphism, always make base class destructors virtual to ensure proper cleanup:

class Base {

public:

virtual ~Base() { // Virtual destructor

cout << "Base destructor" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

private:

int* data;

public:

Derived() {

data = new int[100];

}

~Derived() {

delete[] data;

cout << "Derived destructor" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Base* ptr = new Derived();

delete ptr; // Calls both destructors thanks to virtual

}3. Use the override Keyword

Always use override when overriding virtual functions to catch errors:

class Base {

public:

virtual void process(int x) {

cout << "Base process" << endl;

}

};

class Derived : public Base {

public:

// Typo caught by override keyword

void process(double x) override { // Error! Doesn't match base signature

cout << "Derived process" << endl;

}

};4. Follow the Liskov Substitution Principle

Derived classes should be substitutable for their base classes without breaking functionality:

// Good - Square IS-A Rectangle semantically but violates LSP

class Rectangle {

protected:

double width, height;

public:

virtual void setWidth(double w) { width = w; }

virtual void setHeight(double h) { height = h; }

double getArea() { return width * height; }

};

// Better approach - separate hierarchy or different design

class Shape {

public:

virtual double getArea() = 0;

};

class Rectangle : public Shape {

// Independent width and height

};

class Square : public Shape {

// Single side dimension

};Advanced Inheritance Topics

Final Classes and Methods

The final keyword prevents further inheritance or overriding:

class Base {

public:

virtual void cannotOverride() final {

cout << "This method cannot be overridden" << endl;

}

virtual void canOverride() {

cout << "This method can be overridden" << endl;

}

};

class FinalClass final : public Base {

// This class cannot be inherited from

};

// class WontWork : public FinalClass { // Error!

// };Using Base Class Pointers for Polymorphism

Store different derived class objects in base class pointers for flexible code:

void processShapes(Shape* shapes[], int count) {

for (int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

shapes[i]->draw();

cout << "Area: " << shapes[i]->getArea() << endl;

}

}

int main() {

Shape* shapes[3];

shapes[0] = new Circle("red", 5);

shapes[1] = new Rectangle("blue", 4, 6);

shapes[2] = new Triangle("green", 3, 4, 5);

processShapes(shapes, 3);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

delete shapes[i];

}

}Conclusion: Building Robust Class Hierarchies

Inheritance is one of C++’s most powerful features, enabling you to create sophisticated, maintainable software architectures. Through proper use of base and derived classes, you can build systems where common functionality is shared, specialized behavior is localized, and code reuse is maximized.

The key principles to remember:

- Use public inheritance to model true “is-a” relationships

- Make destructors virtual in base classes when using polymorphism

- Leverage protected members to share functionality with derived classes while maintaining encapsulation

- Override virtual functions to customize behavior in derived classes

- Use abstract classes to define interfaces that derived classes must implement

- Consider composition when inheritance doesn’t represent a true “is-a” relationship

- Follow the Liskov Substitution Principle to ensure derived classes can truly substitute for base classes

Whether you’re building a simple two-level hierarchy or a complex multi-level inheritance structure, the principles remain the same: create logical relationships, maintain encapsulation, and design for extension. With practice, you’ll develop an intuition for when inheritance is the right tool and how to structure your hierarchies for maximum clarity and flexibility.

Mastering inheritance opens the door to advanced C++ techniques like polymorphism, abstract interfaces, and design patterns. It transforms your code from a collection of independent classes into a cohesive, well-organized system that mirrors the logical relationships in your problem domain. This is the essence of object-oriented design, and it’s what makes C++ such a powerful language for building large-scale software systems.