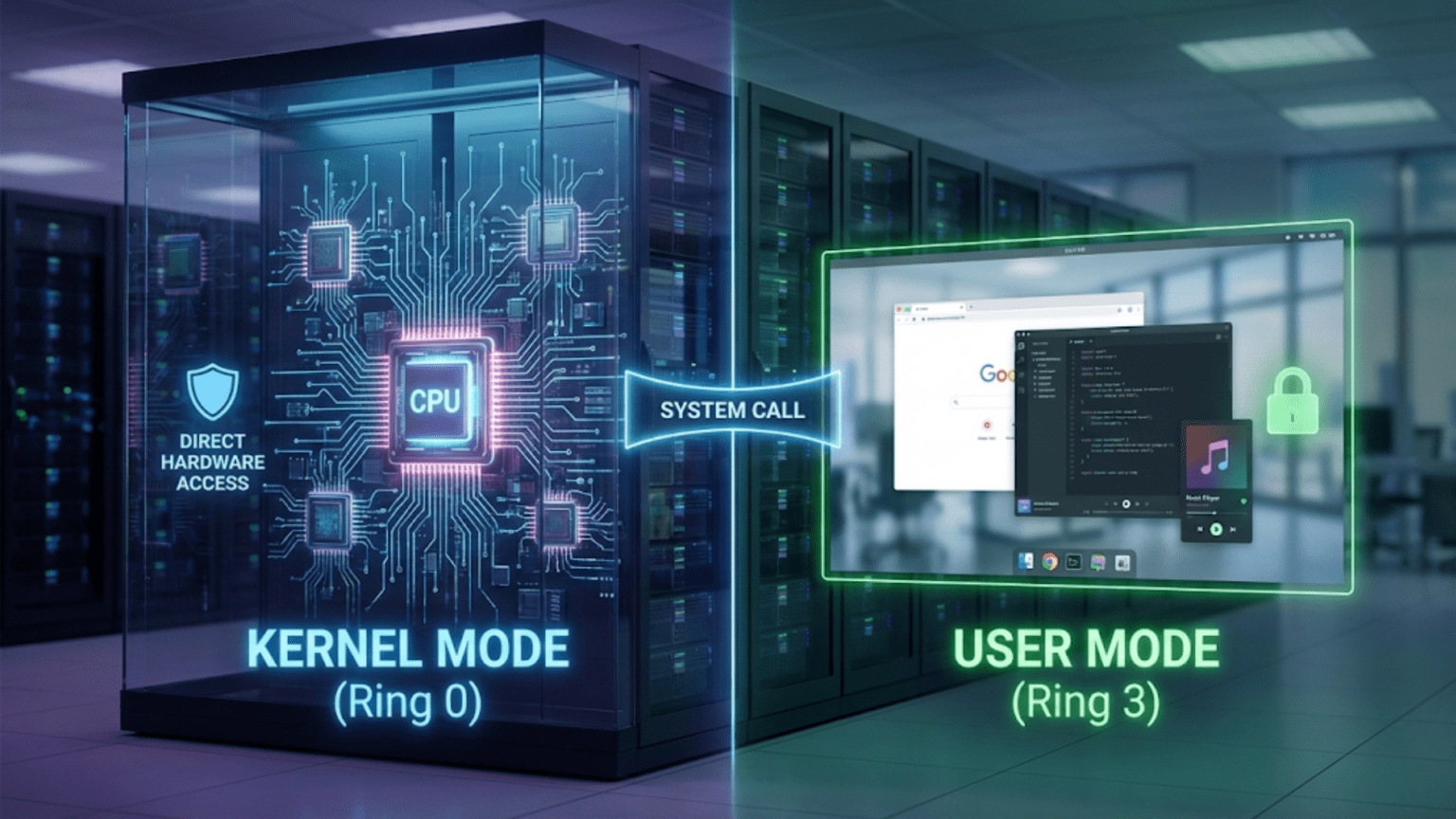

Kernel mode and user mode are two distinct privilege levels at which code executes on a processor, with kernel mode (also called supervisor mode or privileged mode) granting complete access to all hardware, memory, and system resources while user mode restricts access and requires requesting services from the kernel through system calls. This separation prevents user applications from corrupting critical system operations, accessing other processes’ memory, or crashing the entire system when individual programs fail.

When you run an application on your computer, that application doesn’t directly control the hardware—it can’t directly access memory belonging to other programs, can’t execute privileged processor instructions, and can’t communicate with hardware devices without operating system involvement. This restriction exists because your application runs in user mode, a limited execution environment where the operating system strictly controls what code can do. In contrast, the operating system kernel itself runs in kernel mode (also called supervisor mode or privileged mode), where code has unrestricted access to all system resources and hardware. This fundamental division between kernel mode and user mode represents one of the most important architectural features in modern operating systems, providing the foundation for security, stability, and isolation that prevents misbehaving applications from crashing the entire system or accessing data they shouldn’t see.

The concept of execution modes or privilege levels originated in processor architecture, where hardware engineers realized that allowing all code to run with complete system access created intolerable security and stability risks. By implementing multiple privilege levels directly in the CPU and providing mechanisms for the operating system to control which code runs at which level, processors enabled operating systems to enforce strong boundaries between trusted system code and potentially buggy or malicious application code. This hardware-supported privilege separation allows your computer to safely run untrusted applications, isolate processes from each other, protect the operating system from application bugs, and provide controlled interfaces through which applications can request system services. Understanding kernel mode and user mode reveals how your operating system maintains control over the system, how it provides services to applications while protecting itself and other programs, and why certain operations require elevated privileges or administrator access. This comprehensive guide explores what kernel mode and user mode are, how they differ, how processors enforce mode separation, how transitions between modes occur, what code runs in each mode, and why this architectural feature is essential for modern computing security and reliability.

What Kernel Mode and User Mode Are

Kernel mode and user mode represent distinct privilege levels enforced by the processor that determine what operations code is allowed to perform and what resources it can access.

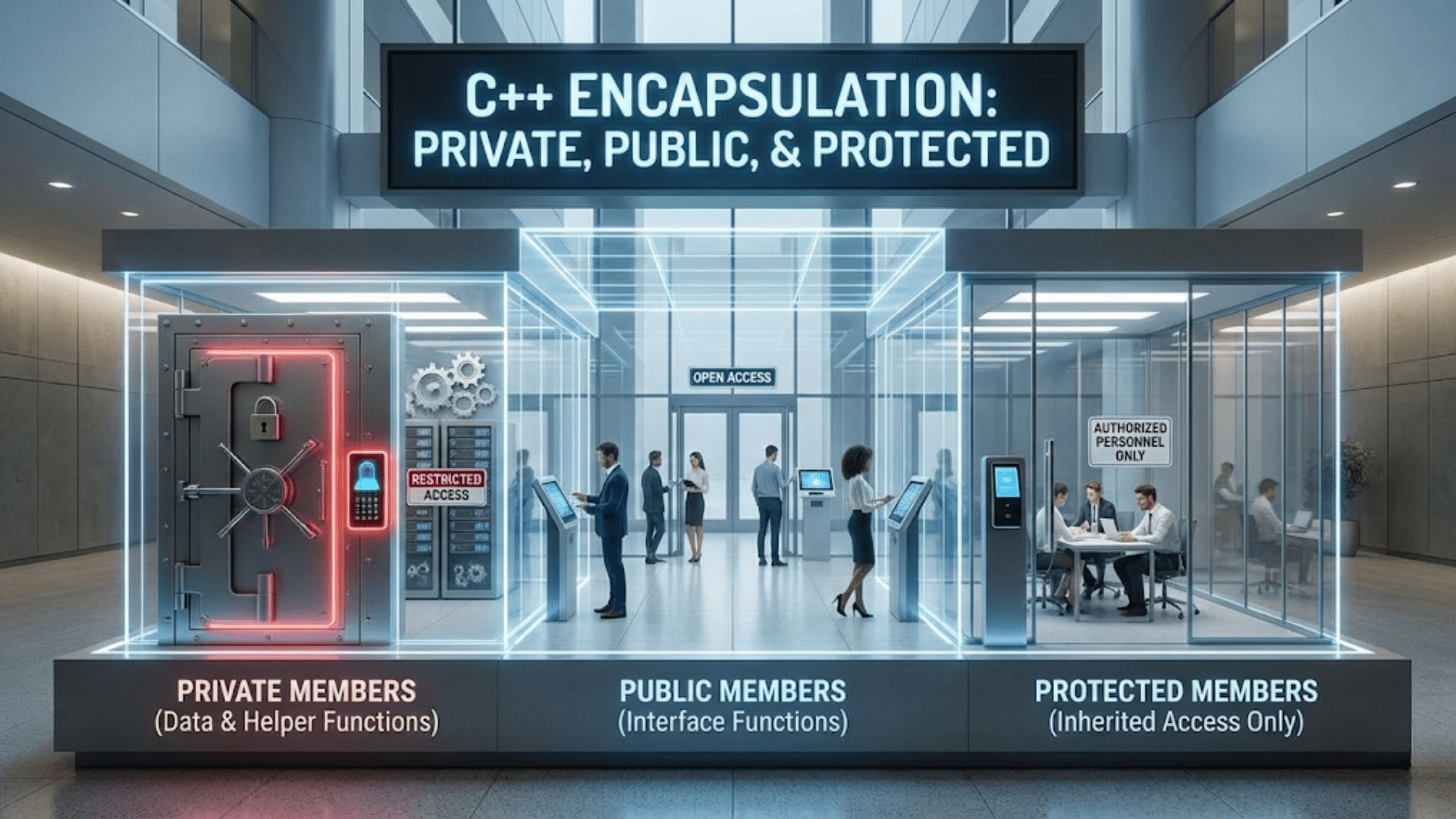

User mode, sometimes called unprivileged mode or restricted mode, is the execution environment where normal applications run. Code executing in user mode faces numerous restrictions designed to prevent it from interfering with system stability or security. User mode code cannot directly access hardware devices, cannot execute privileged processor instructions (like those that modify interrupt handlers or memory management settings), cannot access memory that belongs to the kernel or other processes, cannot disable interrupts or modify system-critical processor state, and cannot directly perform I/O operations to devices. These restrictions protect the system—a bug in user mode code might crash that particular application, but it cannot crash the entire system or corrupt other applications’ data.

Kernel mode, also called supervisor mode, privileged mode, or system mode, is the unrestricted execution environment where the operating system kernel runs. Code executing in kernel mode has complete access to all system resources—it can execute any processor instruction including privileged ones, access any memory address in the system including memory belonging to any process, directly control hardware devices through I/O instructions or memory-mapped I/O, modify system-critical data structures like page tables and interrupt handlers, and enable or disable interrupts. This unrestricted access is necessary for the operating system to perform its management functions, but it also means bugs in kernel mode code can crash the entire system, corrupt any data, or create security vulnerabilities affecting all users.

The processor enforces mode separation through hardware mechanisms. Modern processors include a privilege level indicator in their processor status register—often called the Current Privilege Level (CPL) on x86 processors or similar concepts on other architectures. This indicator tracks whether the processor is currently executing in user mode or kernel mode. The processor checks this privilege level before executing each instruction, and if unprivileged code attempts to execute a privileged instruction or access protected memory, the processor generates an exception (general protection fault on x86, privilege violation on other architectures) that transfers control to the kernel’s exception handler, which typically terminates the offending process.

The transition between modes happens through controlled mechanisms. Applications cannot simply switch themselves to kernel mode—this would defeat the entire purpose of mode separation. Instead, transitions to kernel mode occur through specific, well-defined entry points: system calls (intentional requests from user mode to kernel mode for services), hardware interrupts (external hardware events that require kernel attention), exceptions (CPU-detected error conditions like page faults or illegal instructions), and software interrupts (instruction-generated interrupts similar to system calls). All these mechanisms cause the processor to switch to kernel mode and jump to a kernel-defined handler address, ensuring user code cannot arbitrarily execute in kernel mode.

The concept extends beyond just two modes on some processors. x86 processors support four privilege levels (rings 0-3), with ring 0 being most privileged (used for the kernel) and ring 3 being least privileged (used for applications). Rings 1 and 2 were intended for device drivers and operating system services but are rarely used in modern operating systems, which typically use only ring 0 (kernel) and ring 3 (user). ARM processors use similar concepts with different terminology—Exception Levels (EL0 for user mode through EL3 for secure firmware). The principle remains the same: hardware-enforced privilege levels prevent untrusted code from performing dangerous operations.

Why Mode Separation Is Essential

The separation between kernel mode and user mode isn’t just a theoretical nicety—it provides critical practical benefits that make modern computing possible.

System stability depends on mode separation. In older operating systems without effective mode separation (like MS-DOS or early Windows versions), any application could write to any memory address or execute any instruction. This meant a buggy application could accidentally overwrite operating system code or data structures, causing system crashes or corruption affecting all users. With kernel/user mode separation, bugs in applications are contained—a user mode program that attempts invalid memory access generates an exception that terminates that program, but the kernel and other processes continue running normally. This containment is why modern systems can run for months without restarting despite applications occasionally crashing.

Security enforcement requires mode separation. Many security policies depend on preventing applications from performing certain operations—reading other users’ files, accessing network interfaces without authorization, or modifying system configuration. These restrictions can only be enforced if applications cannot bypass the operating system’s access control mechanisms. Mode separation ensures applications must ask the kernel for services (through system calls), and the kernel checks permissions before performing requested operations. Without mode separation, any application could read any file, intercept network traffic, or modify security settings by directly manipulating hardware.

Process isolation—the ability to prevent processes from accessing each other’s memory—depends on mode separation. The kernel maintains page tables that define which memory each process can access, but these page tables are stored in memory and could be modified by applications if they had kernel mode access. Mode separation ensures only kernel code can modify page tables, enforcing memory isolation. This isolation prevents malicious programs from stealing data from other programs (like password managers or browsers) and prevents buggy programs from corrupting others’ memory.

Device management requires centralized control that mode separation provides. If all applications could directly access hardware devices, chaos would result—multiple programs fighting for disk access, conflicting printer commands, network packets from different applications interfering with each other. Mode separation forces device access through the kernel, which arbitrates access, schedules operations, and ensures orderly sharing of hardware resources.

Reliable resource accounting depends on kernel control. The operating system tracks CPU time, memory usage, and other resources consumed by each process for scheduling decisions, billing in cloud environments, or enforcing quotas. If processes could modify these counters or affect scheduling directly, resource accounting would be meaningless. Mode separation ensures only trusted kernel code manages resources.

Virtualization and sandboxing capabilities build on mode separation. Virtual machines run guest operating systems that think they’re in kernel mode but actually run in a restricted mode, with a hypervisor in true kernel mode mediating access to real hardware. Container systems use kernel features to provide isolated execution environments. These technologies extend the principle of mode separation to create additional layers of privilege and isolation.

How Code Transitions Between Modes

Transitions between user mode and kernel mode must be carefully controlled to maintain security while allowing applications to request system services.

System calls are the primary mechanism for intentional transitions from user mode to kernel mode. When an application needs operating system services—opening a file, creating a process, sending network data, allocating memory—it executes a system call instruction (syscall on modern x86-64, sysenter on older x86, svc on ARM, or software interrupts like int 0x80 on legacy x86). This instruction causes the processor to switch to kernel mode and jump to a kernel-defined system call handler. The application places a system call number (identifying which service is requested) and parameters in specific registers or on the stack. The kernel handler validates parameters, performs the requested operation, places return values in registers, and executes a return-from-system-call instruction that switches back to user mode and resumes application execution. This controlled interface ensures applications can only execute pre-defined kernel functions, not arbitrary kernel code.

Hardware interrupts cause asynchronous transitions to kernel mode when external devices need attention. When a network packet arrives, a disk completes a read operation, a timer reaches its expiration, or a keyboard key is pressed, the device signals an interrupt to the processor. The processor suspends whatever it’s executing (whether user mode or kernel mode code), switches to kernel mode if necessary, and jumps to the interrupt handler registered for that interrupt number. The handler processes the interrupt (reading the data, acknowledging the device, scheduling work), then returns to the interrupted code. Interrupt handlers execute in kernel mode because they need direct hardware access to handle device activity.

Exceptions or traps happen when the processor detects error conditions or special situations requiring kernel intervention. Page faults (accessing memory not currently in RAM), divide-by-zero errors, illegal instruction attempts, or protection violations all generate exceptions. The processor switches to kernel mode and invokes the appropriate exception handler. The kernel might resolve the issue (loading a page from disk for page faults, terminating the process for protection violations) or deliver a signal to the process allowing application-level exception handling. Some exceptions are intentional—debugging breakpoints generate exceptions that debuggers catch and handle.

Context switching between processes involves mode transitions. When the kernel decides to switch from running Process A to Process B (due to time slice expiration, higher-priority process becoming ready, or current process blocking for I/O), this switching happens in kernel mode. A timer interrupt brings the processor into kernel mode where the scheduler saves Process A’s state (registers, program counter), loads Process B’s state, and switches page tables to B’s address space. When the kernel returns to user mode, it returns to Process B instead of Process A, completing the context switch.

Mode transitions have performance costs. Each transition requires saving processor state, switching stacks (user mode and kernel mode typically use separate stacks), potentially flushing processor caches or TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer), executing the kernel code for the system call or interrupt handler, and finally reversing these steps to return to user mode. These costs accumulate—systems making thousands of system calls per second spend considerable time just transitioning between modes. This is why high-performance systems minimize system calls, batch operations when possible, and use techniques like memory-mapped files that reduce kernel transitions for I/O.

Modern processors optimize mode transitions with faster mechanisms. Fast system call instructions (syscall/sysret, sysenter/sysexit) reduce transition overhead compared to older interrupt-based system calls. These specialized instructions perform only the necessary mode switching and register saving/restoring, avoiding unnecessary operations of general interrupt mechanisms.

What Code Runs in Each Mode

Understanding which components run in kernel mode versus user mode clarifies the system architecture and security boundaries.

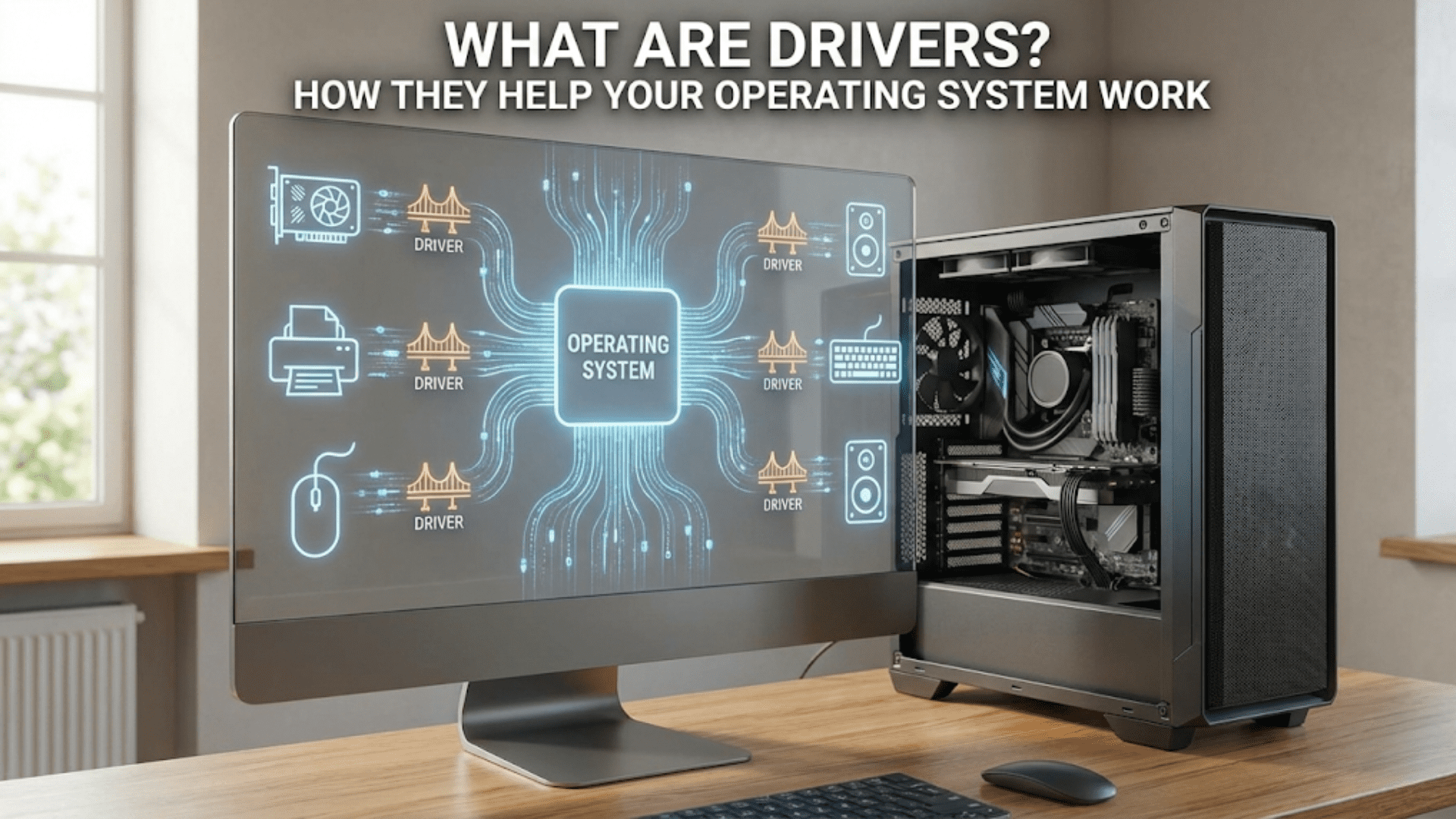

The kernel itself—the core operating system code—runs entirely in kernel mode. This includes the scheduler (deciding which process runs next), memory manager (handling page faults, allocating memory, managing virtual memory), file system code (reading and writing files, managing directories), network stack (processing TCP/IP packets, managing network connections), device drivers (communicating with hardware), and system call handlers (providing services to user mode applications). All this code must run in kernel mode because it needs direct hardware access and must manipulate protected system data structures.

Device drivers traditionally run in kernel mode because they need direct hardware access. A graphics driver must access the graphics card’s memory and registers, a disk driver must send commands to the disk controller, and a network driver must read/write network packets through the network interface card. This kernel mode execution gives drivers great power but also makes them dangerous—buggy drivers cause many system crashes because driver bugs execute with kernel privileges and can corrupt kernel memory or crash the system. Modern operating systems attempt to move more driver functionality to user mode when possible.

System services and daemons run in user mode despite being parts of the operating system. The print spooler, network configuration services, Windows services, or Unix daemons all execute in user mode, making system calls to the kernel when they need privileged operations. This user mode execution limits the damage from bugs in these services—a crash in the print spooler doesn’t crash the kernel.

All applications run in user mode, including your web browser, text editor, media player, games, and other programs. Applications make system calls for any operations requiring kernel services—opening files, creating network connections, allocating memory, creating new processes. The kernel validates all requests and enforces security policies before performing operations on behalf of applications.

Libraries and runtime environments that applications use (like standard C library, .NET Framework, Java Virtual Machine) run in user mode as part of the application process. However, these libraries internally make system calls when applications request operations requiring kernel services. For example, when a Java program writes to a file, the Java runtime library calls the appropriate system call, which transitions to kernel mode where the kernel performs the actual file write.

Shared libraries or DLLs run at the privilege level of the code that loads them. Libraries loaded by user mode applications run in user mode, while libraries loaded by kernel components run in kernel mode. Windows kernel-mode drivers might load kernel-mode DLLs, while user applications load user-mode DLLs.

Some systems implement hybrid approaches. Microkernels minimize kernel mode code, moving device drivers and system services to user mode and keeping only the absolute minimum (basic scheduling, memory management, inter-process communication) in kernel mode. This reduces the amount of code with dangerous privileges, improving reliability and security at the cost of more mode transitions and potential performance overhead. Linux is a monolithic kernel keeping most services in kernel mode for performance, while systems like MINIX, QNX, or Fuchsia use microkernel designs.

User-mode drivers are an increasingly common compromise. Windows supports User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) for certain device types where drivers run in user mode but can still access specific hardware through kernel intermediaries. This provides much of a driver’s functionality in user mode where bugs can’t crash the kernel, with small kernel components handling only the truly privileged operations.

Memory Access and Protection

Kernel mode and user mode have dramatically different memory access rights, enforced by the processor’s memory management unit.

Virtual memory systems assign addresses to different privilege levels. The operating system configures page tables—data structures that map virtual addresses to physical addresses—with permission bits indicating whether each page can be accessed from user mode or requires kernel mode. Typically, the kernel’s code and data structures are mapped in every process’s address space but marked as kernel-mode-only, making them inaccessible to user code. When user mode code attempts to access kernel memory, the processor generates a protection fault, preventing the access.

User space and kernel space divide the virtual address space. On x86-64 Linux, for example, addresses from 0x0000000000000000 to 0x00007FFFFFFFFFFF (lower 128TB) are user space, accessible from user mode, while addresses from 0xFFFF800000000000 to 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF (upper portion) are kernel space, requiring kernel mode. Windows uses similar divisions with specific address ranges for user and kernel. This division allows the kernel to be mapped in every process’s address space (simplifying system calls and interrupts) while preventing user code from accessing it.

The memory management unit (MMU) enforces access permissions. Every memory access goes through the MMU, which checks the processor’s current privilege level against the page’s permission bits. User mode code can only access user-space pages; kernel mode code can access both user-space and kernel-space pages. This hardware enforcement is inescapable—there’s no software workaround that bypasses the MMU’s permission checks.

System calls that pass pointers from user space require careful kernel handling. When a user program calls read(fd, buffer, count) to read from a file, it passes a pointer to buffer where data should be written. The kernel must verify this pointer points to valid user-accessible memory before writing to it. If the kernel blindly writes to the user-provided address, malicious programs could trick the kernel into overwriting kernel memory by passing kernel-space addresses as the buffer pointer. Modern kernels include functions like copy_to_user() and copy_from_user() that safely transfer data between kernel and user space with proper permission checking.

Shared memory regions allow user processes to map the same physical memory for efficient inter-process communication. The kernel sets up page table entries in multiple processes pointing to the same physical pages, allowing processes to read and write shared memory from user mode without kernel involvement for each access. The kernel still controls setting up these shared regions, enforcing permissions about which processes can access which shared memory.

Direct memory access (DMA) from devices complicates the picture. Network cards, disk controllers, and other devices can write directly to physical memory through DMA, bypassing the CPU and MMU. This requires the kernel to carefully manage DMA buffers, ensuring devices can only DMA to appropriate memory regions. IOMMU (I/O Memory Management Unit) on modern systems provides protection, preventing devices from DMAing to arbitrary memory.

Privilege Escalation and Security

Understanding kernel/user mode boundaries is essential for security because compromising kernel mode grants complete system control.

Privilege escalation attacks attempt to execute code in kernel mode from user mode starting point. If attackers can inject code that runs in kernel mode, they gain complete system control—they can read all memory, modify any files, hide their presence, or install rootkits. Most serious security vulnerabilities involve privilege escalation in some form.

Buffer overflow vulnerabilities in kernel code can lead to privilege escalation. If a system call handler has a buffer overflow bug, attackers can craft system calls that overflow buffers, overwriting kernel memory and potentially executing attacker-controlled code in kernel mode. Mitigations like stack canaries, ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization), and DEP (Data Execution Prevention) make exploitation harder but don’t eliminate risks entirely.

Driver vulnerabilities are common privilege escalation vectors. Since drivers run in kernel mode, bugs in drivers provide kernel mode access to attackers. Malicious drivers (if attackers can load them) grant immediate kernel access. This is why modern operating systems require driver signing—only drivers cryptographically signed by trusted parties can load, preventing easy installation of malicious kernel-mode code.

Sudo and administrative privileges relate to but differ from kernel mode. When you use sudo on Unix or run a program “as administrator” on Windows, you’re still running in user mode—you’re just running as a user account with more permissions. The kernel enforces these permissions through access control lists and ownership checks. Administrator privileges grant ability to make system configuration changes and access restricted files, but even administrators’ processes run in user mode and cannot directly execute privileged processor instructions or access arbitrary memory.

Rootkits operate in kernel mode to hide their presence. Once attackers achieve kernel mode access, they can modify kernel code or data structures to hide files, processes, or network connections from monitoring tools. Kernel-mode rootkits are extremely difficult to detect because they can subvert the very tools used to detect them.

Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities demonstrated that even hardware-enforced mode separation isn’t perfect. These CPU vulnerabilities allowed user mode code to read kernel memory through side-channel attacks exploiting speculative execution. Mitigations involved kernel patches (KPTI – Kernel Page Table Isolation), microcode updates, and performance costs. These vulnerabilities showed that the security boundary between modes depends on correct hardware implementation, not just software design.

Virtualization adds complexity with hypervisors running in a privilege level above the kernel. Guest operating system kernels think they’re in kernel mode but actually run in a restricted mode, with the hypervisor in the truly privileged level. Hardware virtualization support (Intel VT-x, AMD-V) provides additional privilege levels specifically for virtualization.

Performance Implications

The kernel/user mode separation affects system performance in various ways.

System call overhead consists of the time spent transitioning between modes plus the time executing in the kernel. Fast paths in the kernel minimize overhead for common operations, but frequent system calls can significantly impact performance. Applications that make thousands of system calls per second spend considerable time in mode transitions.

vDSO (virtual Dynamic Shared Object) on Linux and similar mechanisms on other systems reduce overhead for frequently used system calls. These mechanisms map read-only kernel data into user space, allowing applications to read certain information (like current time) without system calls. Functions like clock_gettime can execute entirely in user mode when using vDSO.

Batching operations reduces system call frequency. Reading or writing data in large chunks through fewer system calls performs better than many small operations. Memory-mapped files allow applications to access file contents through normal memory operations rather than read/write system calls, eliminating system call overhead for each access.

Context switch overhead includes both mode transition costs and the need to save/restore process state and switch memory address spaces. Frequent context switching degrades performance, which is why schedulers try to minimize unnecessary switching while maintaining responsiveness.

CPU cache effects relate to mode transitions. Switching to kernel mode may flush certain caches, and kernel code may evict application data from caches. Frequent transitions increase cache miss rates, slowing execution.

TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) flushes or tagging affect performance. Address space switches during context switching may require TLB flushes, losing the cached virtual-to-physical address translations. Tagged TLBs alleviate this by associating each entry with an address space identifier, avoiding complete flushes.

Microkernels perform more mode transitions because more functionality runs in user mode, potentially impacting performance compared to monolithic kernels. This overhead is why Linux and Windows use monolithic kernel designs despite microkernel security advantages.

Conclusion

The separation between kernel mode and user mode represents a fundamental architectural principle in modern operating systems, providing the foundation for security, stability, and isolation that makes contemporary computing possible. This hardware-enforced privilege separation—where untrusted application code runs in restricted user mode while the operating system kernel runs with complete system access in kernel mode—prevents application bugs from crashing entire systems, enforces security policies that applications cannot bypass, enables process isolation that protects programs from each other, and allows orderly sharing of hardware resources under kernel control.

Understanding kernel mode and user mode clarifies much about how operating systems work: why applications must make system calls for privileged operations, why device drivers require special installation and pose security risks, why administrator privileges don’t grant complete system access, how operating systems protect themselves from buggy or malicious applications, and why certain operations are slow while others are fast. This knowledge helps in debugging (kernel debuggers operate differently than user debuggers), security analysis (privilege escalation attacks target kernel mode access), performance optimization (minimizing system calls improves performance), and system administration (understanding what operations require kernel involvement).

As computing evolves with virtualization adding hypervisors above kernel mode, containers providing lightweight isolation within kernel-controlled boundaries, and new processor architectures introducing additional privilege levels or security domains, the fundamental principle endures: separating trusted system code with complete access from untrusted application code with restricted access creates the security and stability foundation modern computing depends upon. Whether you’re an application developer minimizing system calls for performance, a security researcher analyzing vulnerabilities, a system administrator managing servers, or a curious user wanting to understand your computer’s architecture, comprehending the kernel/user mode boundary illuminates one of the most important concepts in operating system design—the privilege separation that protects your system from chaos while allowing the functionality you depend upon.

Summary Table: Kernel Mode vs. User Mode Comparison

| Aspect | Kernel Mode (Supervisor/Privileged) | User Mode (Unprivileged/Restricted) |

|---|---|---|

| Processor Privilege Level | Ring 0 (x86), EL1/EL2 (ARM), highest privilege | Ring 3 (x86), EL0 (ARM), lowest privilege |

| Memory Access | Can access all memory including user space and kernel space | Can only access user space memory; kernel space access causes fault |

| Instruction Access | Can execute all processor instructions including privileged ones | Cannot execute privileged instructions; attempting causes exception |

| Hardware Access | Direct access to all hardware devices via I/O or memory-mapped I/O | No direct hardware access; must request through kernel |

| Interrupt Control | Can enable/disable interrupts, modify interrupt handlers | Cannot control interrupts |

| Page Table Modification | Can modify page tables, control memory mappings | Cannot modify page tables |

| Process State Access | Can access and modify any process’s state | Can only access own process state |

| Common Code Types | Kernel core, device drivers, interrupt handlers, system call handlers | Applications, user libraries, user-mode services |

| Error Impact | Bugs can crash entire system, corrupt any data | Bugs typically crash only that process |

| Entry Mechanisms | Boot, interrupts, exceptions, return from user mode | System calls, return from interrupt/exception |

| Exit Mechanisms | System call return, interrupt return, context switch to user process | System calls, exceptions (unintentional) |

| Stack Location | Kernel stack (separate per-process or global) | User stack in user memory |

| Performance | Overhead to enter/exit, but direct hardware access | No mode transition overhead for user operations |

| Security Risk | Complete system compromise if exploited | Limited to process scope |

System Call Transition Flow:

| Step | Mode | Action | Example (Linux read syscall) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Setup | User | Application prepares system call number and parameters | syscall_number = SYS_read<br>rdi = fd, rsi = buffer, rdx = count |

| 2. Invoke | User | Execute system call instruction | syscall instruction |

| 3. Switch | Transition | Processor switches to kernel mode, jumps to kernel entry | Hardware switches to ring 0, jumps to kernel |

| 4. Dispatch | Kernel | Kernel identifies syscall, validates parameters | Check syscall number, verify buffer pointer |

| 5. Execute | Kernel | Kernel performs requested operation | Read from file, copy data to buffer |

| 6. Return Setup | Kernel | Place return value in register | rax = bytes_read or error code |

| 7. Return | Transition | Execute return instruction, switch to user mode | sysret instruction |

| 8. Continue | User | Application continues with results | Process returned data |

What Runs in Each Mode:

| Component | Execution Mode | Reason | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Core | Kernel | Needs full hardware access, manages system | Process scheduler, memory manager |

| Device Drivers | Kernel (traditional) | Direct hardware access required | Graphics driver, disk driver, network driver |

| User-Mode Drivers | User | Safety; limited hardware access through kernel | Some USB drivers, printer drivers (UMDF) |

| System Services | User | Isolation; uses syscalls for privileged ops | Print spooler, network services |

| Applications | User | Untrusted; must be restricted | Web browser, text editor, games |

| Shared Libraries | User (mostly) | Run in context of loading process | libc, .NET Framework, Java runtime |

| Interrupt Handlers | Kernel | Handle hardware interrupts, need device access | Timer interrupt, disk I/O completion |

| Exception Handlers | Kernel | Handle CPU exceptions, enforce protection | Page fault handler, divide-by-zero |

| Hypervisor | Higher than Kernel | Manages virtual machines | VMware ESXi, KVM, Hyper-V |

Common Privilege Escalation Vectors:

| Attack Vector | Description | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Kernel Buffer Overflow | Exploit buffer overflow in kernel code to execute arbitrary kernel code | Stack canaries, ASLR, bounds checking, code review |

| Driver Vulnerabilities | Exploit bugs in kernel-mode drivers | Driver signing, WHQL certification, reduced kernel attack surface |

| Malicious Driver Loading | Load malicious driver to gain kernel access | Require signed drivers, Secure Boot, kernel lockdown |

| System Call Exploits | Pass crafted parameters that exploit syscall handler bugs | Input validation, safe memory access functions |

| Use-After-Free | Exploit freed kernel memory still accessible | Memory sanitizers, reference counting, safer languages |

| Race Conditions | Exploit timing windows in kernel code | Proper locking, atomic operations, formal verification |

| Spectre/Meltdown | Side-channel attacks reading kernel memory from user mode | KPTI, microcode updates, compiler mitigations |