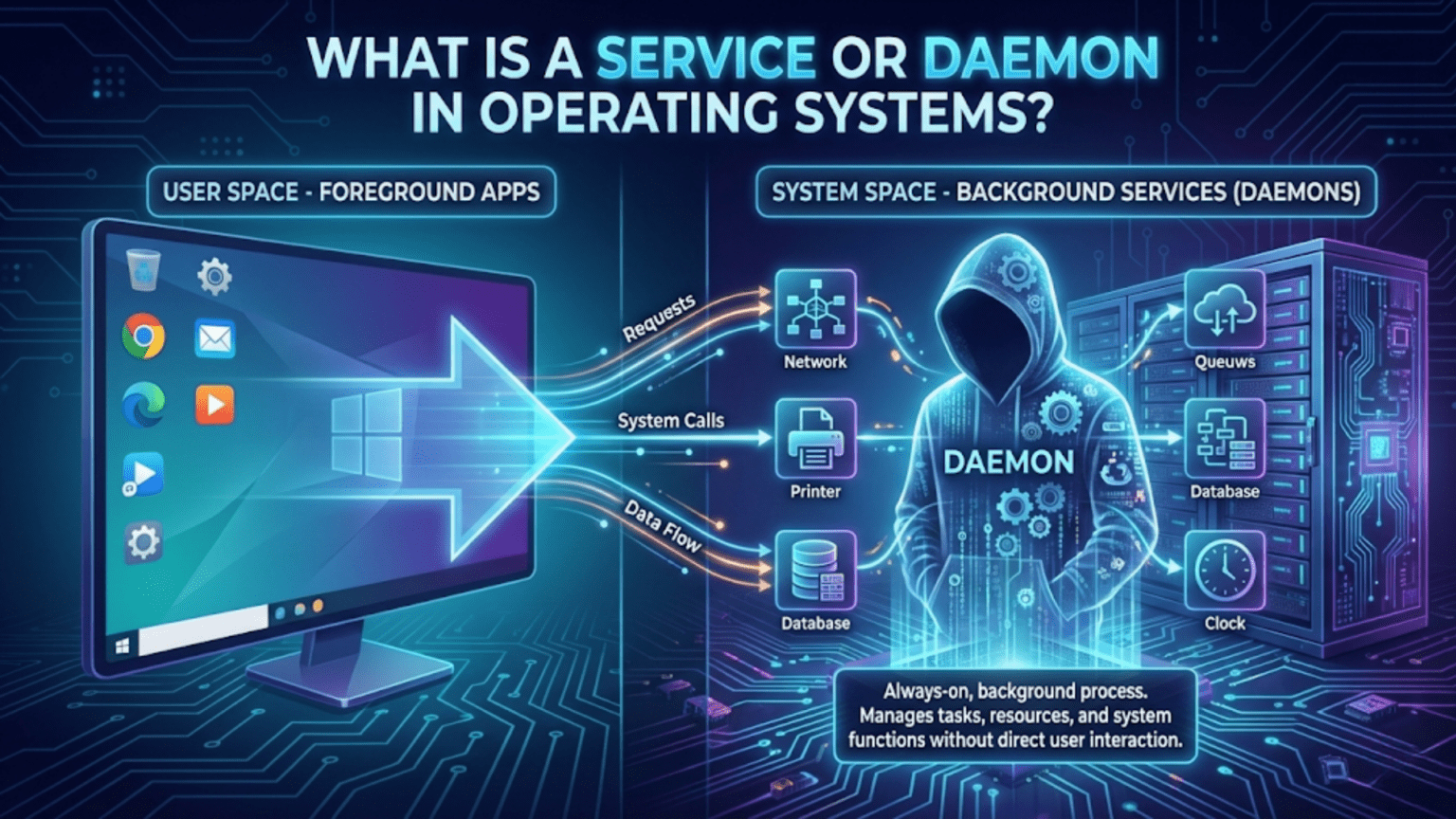

A service (in Windows) or daemon (in Unix-like systems) is a background process that runs continuously without direct user interaction, performing system tasks or providing functionality to other programs. These processes start automatically when the operating system boots, run in the background handling tasks like network communication, printing, system monitoring, and database operations, and continue operating even when no users are logged in, making them essential for core operating system functionality and server operations.

Your computer is constantly working even when you’re not actively using it. Web servers respond to requests, databases process queries, antivirus programs scan for threats, backup systems copy files, print spoolers manage printing jobs, and network services maintain connectivity—all without requiring your attention or intervention. These background workers are called services on Windows and daemons on Unix-like systems (Linux, macOS, BSD), and they represent a fundamental architectural component that enables modern operating systems to provide continuous functionality, respond to events, and maintain operations independently of user sessions. Understanding services and daemons reveals the invisible infrastructure that makes your computer useful beyond just running applications you directly interact with, providing the foundation for everything from network connectivity to system monitoring to server operations.

Services and daemons solve a critical problem in operating system design: how to perform ongoing background tasks reliably without requiring constant user presence or interaction. Before services existed, many background tasks required either dedicated programs running in terminal windows (which closed when you logged out) or elaborate workarounds to keep processes running continuously. Services and daemons formalized the concept of background processes, giving them special status in the operating system with mechanisms for automatic startup, lifecycle management, monitoring, and control. This formalization enables the reliable, persistent background processing that modern computing depends upon, from desktop computers maintaining network connections to servers hosting websites and handling thousands of concurrent client connections. This comprehensive guide explores what services and daemons are, how they differ from regular processes, how different operating systems implement and manage them, common examples and their purposes, how to control and configure them, and best practices for developing and deploying background services.

What Services and Daemons Are

Services (Windows terminology) and daemons (Unix/Linux terminology) are specialized background processes designed to run continuously, typically without direct user interaction, providing ongoing functionality to the operating system or other applications.

The fundamental characteristic distinguishing services from regular applications is their execution model. Regular applications are interactive—they display user interfaces, respond to user input, and typically run only when explicitly launched and terminate when closed. Services and daemons, by contrast, run in the background with no user interface (they might have administrative interfaces, but no windows or dialogs for regular operation), start automatically when the system boots or under specific conditions, run independently of user login sessions (they continue running even when no users are logged in), and persist until explicitly stopped or the system shuts down.

Services and daemons typically perform one of several categories of functions. System services provide core operating system functionality—network connectivity, hardware device management, file system operations, security enforcement, and other fundamental system capabilities. Application services support specific applications by providing backend functionality—database servers, web servers, email servers, and messaging systems all run as services. Monitoring and maintenance services perform ongoing system management tasks—antivirus scanning, system backup, disk cleanup, update checking, and performance monitoring. Integration services enable communication between different software components—print spoolers, clipboard managers, and interprocess communication brokers.

The term “daemon” originates from Greek mythology where daemons were supernatural beings working invisibly to make things happen. MIT programmers adopted this term in the 1960s for background processes that quietly perform tasks without human intervention, and the name stuck throughout Unix history. The term “service” is more straightforward and business-oriented, reflecting Microsoft’s preference for less whimsical terminology. Despite the different names, the concepts are fundamentally similar—background processes providing ongoing functionality.

Services and daemons differ from foreground processes in several technical aspects. They typically have no controlling terminal (on Unix systems) or console window (on Windows), run at system privileges or under specific service accounts rather than user accounts, are managed by specialized system service managers (systemd, launchd, Windows Service Control Manager), and often implement specific programming patterns like daemonization (detaching from the parent process, closing file descriptors, creating a new session) to properly function as background processes.

The lifecycle of a service or daemon includes several distinct states. The stopped state means the service is registered but not currently running. The starting state is transitional while the service initializes. The running state means the service is actively executing and providing its functionality. The stopping state is transitional during shutdown. Some systems add additional states like paused (temporarily suspended but can resume without full restart) or failed (terminated abnormally). System service managers track these states and provide mechanisms to transition between them.

Services and daemons enable the server model of computing where a computer continuously provides services to clients rather than just running applications when users are present. Web servers, database servers, file servers, email servers, and countless other server applications all function as services, running continuously and responding to client requests whenever they arrive.

How Windows Services Work

Windows implements background services through the Windows Service Control Manager (SCM), a system component that manages service lifecycle, startup, configuration, and monitoring.

Windows services are executable programs (typically .exe files) that implement a specific interface required for service operation. Unlike regular applications with a main() function that executes and terminates, service programs implement a ServiceMain() function that the Service Control Manager calls when starting the service. This function typically initializes the service, registers a handler function for control requests (start, stop, pause, continue), and then enters a long-running loop or waits for events, continuing execution until told to stop.

The Service Control Manager maintains a database of installed services in the Windows Registry under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services. Each service has a registry key containing configuration: the executable path (ImagePath), service display name, service type (own process, shared process, kernel driver, etc.), start type (automatic, manual, disabled), dependencies on other services, the account the service runs under, and various other parameters.

Service startup types determine when services start. Automatic services start automatically when Windows boots, before any user logs in. Automatic (Delayed Start) services start shortly after boot completes, reducing boot time contention among services. Manual services don’t start automatically but can be started on demand by users, applications, or dependent services. Disabled services cannot start until re-enabled. Boot and System start types exist for device drivers that must load during early boot stages.

Windows services run under specific accounts that determine their privileges and access rights. The LocalSystem account has extensive system privileges and can access network resources as the computer account. The LocalService account has minimal privileges and accesses network resources as an anonymous user. The NetworkService account has similar limited privileges but accesses network resources as the computer account. Services can also run under custom user accounts, which administrators create specifically for service operations with only necessary privileges (following the principle of least privilege).

Service dependencies ensure services start in correct order when they rely on other services. If Service A depends on Service B, Windows ensures Service B starts before attempting to start Service A. If Service B fails to start, Service A won’t start either. This dependency system handles the complexity of service initialization order automatically, preventing failures from starting services before their dependencies are ready.

Windows provides several tools for managing services. The Services MMC snap-in (services.msc) provides a graphical interface showing all services, their status, startup type, and associated accounts, with the ability to start, stop, pause, and configure services. The sc.exe command-line tool offers comprehensive service control: “sc query” lists services, “sc start servicename” starts a service, “sc stop servicename” stops it, “sc config servicename start= auto” changes startup type, and many other operations. PowerShell provides Get-Service, Start-Service, Stop-Service, and Set-Service cmdlets for service management with full scripting capabilities.

Service recovery actions define what happens when a service fails. Windows can automatically restart the service after a delay, restart the computer, or run a recovery program. These recovery actions can differ for first, second, and subsequent failures, allowing escalating responses to persistent problems. This automatic recovery improves reliability by handling transient failures without manual intervention.

How Unix/Linux Daemons Work

Unix-like systems have evolved through several daemon management systems, from traditional init to modern systemd, each with different capabilities and philosophies.

Traditional Unix daemons follow a specific creation pattern called daemonization. A program daemonizes by forking to create a child process, having the parent exit (so the shell thinks the command completed), creating a new session with setsid() to detach from the controlling terminal, forking again and having the first child exit (ensuring the daemon can’t reacquire a controlling terminal), changing the working directory to root (/) to avoid preventing filesystem unmounts, closing standard file descriptors (stdin, stdout, stderr) and often redirecting them to /dev/null, and optionally writing its process ID to a PID file. This elaborate dance ensures the daemon runs truly in the background, independent of the terminal or session that started it.

The init system (the first process that starts during boot, always with PID 1) historically managed daemons. Traditional System V init used shell scripts in /etc/in.it.d/ to start, stop, and manage daemons. These scripts implemented standard actions: start (launch the daemon), stop (terminate it), restart (stop and start), reload (tell the daemon to reload configuration), and status (report whether it’s running). Init ran these scripts at specific runlevels (system states like single-user mode, multi-user mode, graphical mode) to start appropriate daemons for each system state.

Upstart, developed by Ubuntu, improved on System V init with event-based daemon management. Instead of just runlevels, Upstart could start daemons in response to various system events, better handling dependencies and providing automatic respawning of crashed daemons. Configuration files in /etc/in.it/ described each daemon with its start conditions, stop conditions, and execution commands.

systemd is the modern init system used by most current Linux distributions. systemd introduces unit files (ending in .service for service units) stored in /etc/systemd/sys.tem/ or /lib/systemd/sys.tem/. These INI-style configuration files declare the service’s executable, startup dependencies, restart behavior, resource limits, and numerous other parameters. systemd handles dependency resolution, parallel startup for faster boot times, socket activation (daemons can be started on-demand when clients connect to their sockets), and comprehensive logging integration with journald.

A typical systemd service unit file contains several sections. The [Unit] section includes description, documentation links, and ordering dependencies (After=, Before=, Requires=, Wants=). The [Service] section specifies the service type (simple, forking, oneshot, notify, etc.), the executable command, working directory, user/group to run as, restart behavior, and environment variables. The [Install] section defines installation dependencies, particularly which target (similar to runlevels) should include this service.

systemctl is the primary command for managing systemd services. “systemctl start servicename” starts a service, “systemctl stop servicename” stops it, “systemctl restart servicename” restarts it, “systemctl reload servicename” reloads configuration without restarting, “systemctl enable servicename” configures automatic startup at boot, “systemctl disable servicename” prevents automatic startup, “systemctl status servicename” shows detailed status including recent log entries, and “systemctl list-units –type=service” lists all services.

macOS uses launchd as its service management system. Launch daemons (system-wide services) have configuration plist files in /Library/LaunchDaemons/, while launch agents (per-user services) use /Library/Launch.Agents/ or ~/Library/Launch.Agents/. These XML property list files specify the program to run, when to run it, environment settings, resource limits, and other parameters. The launchctl command manages launchd: “launchctl load” loads a service, “launchctl unload” unloads it, “launchctl start” starts it, and “launchctl list” shows loaded services.

Common Services and Daemons

Understanding what services and daemons are becomes concrete by examining common examples that most systems run.

The SSH daemon (sshd) provides secure remote shell access to Unix-like systems. It listens on port 22 for incoming SSH connections, authenticates users, and creates shell sessions for authenticated connections. This daemon enables remote system administration and secure file transfer, running continuously so administrators can access the system whenever needed.

Web server daemons like Apache (httpd) or nginx serve web content. They listen on ports 80 (HTTP) and 443 (HTTPS), accepting client requests, processing them (possibly executing server-side code), and returning responses. Web servers run as daemons to provide continuous availability—websites must be accessible 24/7 regardless of whether administrators are logged in.

Database server daemons like MySQL (mysqld), PostgreSQL, or Microsoft SQL Server manage database operations. They handle client connections, process queries, manage transactions, ensure data integrity, and perform maintenance operations like backup and optimization. Databases run as services because applications need database access continuously, and starting/stopping them for each query would be prohibitively slow.

The Domain Name System daemon (named or bind) provides DNS resolution, translating domain names to IP addresses. DNS servers must run continuously because name resolution requests arrive unpredictably and must be answered quickly.

Print spooler services (spoolsv.exe on Windows, CUPS on Linux/macOS) manage printing. They queue print jobs, communicate with printers, handle printer status, and process print requests from applications. Running as a service allows print jobs to be queued even when the user logs out, with actual printing happening whenever the printer is ready.

The cron daemon (crond) executes scheduled tasks on Unix-like systems. It reads crontab files specifying commands to run at specific times, executing them as scheduled. The Windows Task Scheduler service serves the same purpose on Windows. These services enable automated maintenance tasks like backups, log rotation, and system updates.

Network time daemons (ntpd, chronyd, or Windows Time Service) synchronize system time with network time servers. Accurate time is critical for security protocols, log correlation, and distributed systems, requiring continuous time synchronization.

The system logging daemon (syslogd, rsyslogd, or Windows Event Log service) receives and stores log messages from the operating system and applications. Logging services run continuously to capture all events as they occur.

Antivirus and security services continuously monitor the system for threats. Windows Defender runs as multiple services, Linux systems might run ClamAV daemon (clamd), and enterprise systems run various security monitoring agents. These services must run continuously to provide real-time protection.

Network connectivity services manage network interfaces and connections. NetworkManager daemon on Linux, networkd on systemd systems, and Network Service on Windows handle network configuration, connection establishment, and ongoing connectivity management.

Container and virtualization daemons like Docker (dockerd) or libvirtd manage containers or virtual machines. These services provide APIs for creating, starting, stopping, and monitoring containers/VMs, running persistently to manage the lifecycle of virtualized workloads.

Service Dependencies and Startup Order

Services often depend on other services, requiring careful management of startup order to ensure the system reaches a functional state reliably.

Direct dependencies occur when one service explicitly requires another to function. A web application service might depend on a database service—there’s no point starting the web application if the database isn’t available. A file sharing service might depend on the network service—you can’t share files over the network without network connectivity. Service managers must start dependencies before dependent services.

Implicit dependencies arise from resource requirements rather than explicit declarations. A service might need the file system fully mounted, network interfaces configured, or system time synchronized, even without explicitly declaring dependencies on services providing these capabilities. Modern service managers attempt to infer these dependencies or provide ways to declare them.

Circular dependencies create problems when Service A depends on Service B, which depends on Service C, which depends on Service A. Such circular chains prevent any service in the loop from starting. Service managers detect circular dependencies and either break them intelligently or fail with errors, requiring configuration fixes.

Startup ordering in systemd uses Before= and After= directives in unit files. If Service A declares “After=network.target”, systemd ensures the network target is reached before starting Service A. This declarative approach lets systemd determine optimal startup order, potentially starting independent services in parallel for faster boot.

Dependency types vary in strictness. Required dependencies (Requires= in systemd, dependency list in Windows service configuration) mean the service cannot function without the dependency—if the dependency fails, the dependent service doesn’t start. Optional dependencies (Wants= in systemd) indicate preference but not requirement—the service starts even if the optional dependency fails. Conflicting dependencies (Conflicts= in systemd) prevent simultaneous operation of conflicting services.

Target states or runlevels group related services. Windows has no equivalent concept, starting services individually based on their configuration. Traditional Unix used runlevels 0-6 (0=halt, 1=single-user, 2-5=multi-user variants, 6=reboot). systemd uses targets like multi-user.target (command-line multi-user system) or graphical.target (graphical desktop system), with services declaring which targets should include them.

Dependency resolution determines startup order. The service manager builds a dependency graph from all service declarations, topologically sorts it to find a valid startup order, identifies cycles or unresolvable dependencies, and then starts services following the computed order. Sophisticated managers like systemd parallelize independent services to reduce boot time.

Failure handling propagates through dependencies. If a required dependency fails to start, the dependent service typically doesn’t start, and services depending on it also don’t start. This cascading failure prevents attempting to run services that can’t possibly function. Recovery actions might restart failed dependencies and retry dependent services.

Controlling and Configuring Services

Managing services involves starting, stopping, configuring automatic startup, changing settings, and monitoring status—operations that vary by operating system and service manager.

Manual service control allows starting and stopping services on demand. On Windows, you can right-click a service in the Services MMC and select Start, Stop, Pause, or Resume. The sc command provides equivalent functionality: “sc start ServiceName” and “sc stop ServiceName”. PowerShell offers Start-Service and Stop-Service cmdlets. On Linux with systemd, “systemctl start servicename” and “systemctl stop servicename” control services. The launchctl command manages macOS services.

Automatic startup configuration determines whether services start at boot. Windows services can be set to Automatic (starts at boot), Automatic (Delayed Start) (starts shortly after boot completes), Manual (only starts when explicitly requested), or Disabled (cannot start). The Services MMC allows changing startup type, as do sc config and Set-Service commands. On systemd, “systemctl enable servicename” creates symbolic links that cause the service to start at boot, while “systemctl disable servicename” removes these links. The actual service enablement creates links in /etc/systemd/sys.tem/multi-user.target.wants/ or similar directories.

Service configuration modifies how services operate. Configuration typically lives in files the service reads at startup—/etc/service.name/ on Unix, configuration files in Program Files on Windows, or parameters in service unit files. After changing configuration, services usually need restarting or reloading. Some services support reload operations that reread configuration without fully restarting, minimizing disruption. The “systemctl reload servicename” or “sc control servicename 128” (paramchange) commands trigger reloads.

Service accounts and permissions control what services can access. Windows services can run under built-in accounts (LocalSystem, LocalService, NetworkService) or custom accounts. Changing service accounts affects what files and resources the service can access. On Unix, services typically run as specific users (www-data for web servers, mysql for MySQL, etc.) with limited permissions. The User= and Group= directives in systemd unit files specify service accounts.

Resource limits can be imposed on services to prevent resource exhaustion. Linux cgroups (control groups) allow limiting CPU, memory, and I/O resources for services. systemd exposes this through directives like MemoryLimit=, CPUQuota=, and IOWeight= in unit files. Windows Job Objects provide similar capabilities, with some resource controls available through sc or PowerShell.

Service monitoring shows current status and resource usage. The “systemctl status servicename” command shows detailed service status including recent log output, process tree, memory usage, and CPU time. Windows Services MMC shows status and Task Manager reveals resource usage by service processes. Third-party monitoring tools provide more comprehensive service monitoring with alerting on failures or resource issues.

Querying service information reveals detailed service configuration and state. On Linux, “systemctl show servicename” outputs all properties of a service. “sc qc ServiceName” and “sc query ServiceName” on Windows show service configuration and current state. This information is useful for troubleshooting, documentation, or automation scripts.

Developing Services and Daemons

Creating custom services or daemons requires following platform-specific patterns and best practices to ensure reliable background operation.

Windows service development typically uses the .NET ServiceBase class or Win32 API functions for lower-level control. A Windows service application registers a service main function with the Service Control Manager, implements handlers for start, stop, pause, and continue control requests, and performs its work in a separate worker thread while the main service thread remains responsive to control requests. Services must respond to control requests within timeouts (typically 30 seconds) or Windows considers them hung.

The service registration and installation process requires creating a service using the CreateService API or the installutil.exe tool for .NET services. This registration creates the service’s entry in the SCM database. Uninstalling uses DeleteService or installutil.exe with the /u flag. Services can be debugged by attaching a debugger to the running service process, though special techniques may be needed since services start at boot without user interaction.

Unix daemon development traditionally required the daemonization procedure described earlier, but systemd simplifies this. Services can run as simple foreground processes (Type=simple in unit files) with systemd handling the background execution. This approach eliminates the error-prone daemonization code. For compatibility with older systems or when running under multiple init systems, daemons might still implement traditional daemonization.

Signal handling is critical for Unix daemons. SIGHUP typically triggers configuration reload, SIGTERM requests graceful shutdown, and SIGKILL forces immediate termination. Well-written daemons install signal handlers for these signals, performing appropriate actions. On Windows, services use control handler functions registered with RegisterServiceCtrlHandler to respond to control requests.

Logging from services and daemons requires special consideration since they don’t have standard output or error streams. Windows services typically use the Event Log API to write to Windows Event Logs. Unix daemons traditionally used syslog() to send messages to the system logger, though modern daemons might write directly to files or use structured logging to systemd journal. Logging should include appropriate severity levels, timestamps, and context information.

Configuration management for services can use configuration files, environment variables, command-line arguments (though less common for services), or registry/database settings. Configuration files should support reloading without service restart where practical. Validation of configuration at startup prevents running with invalid settings that might cause failures later.

Error handling and recovery in services must be robust. Services should catch and log exceptions rather than crashing, implement retry logic for transient failures, and expose health check endpoints or status information that monitoring systems can query. Automatic restart on failure (configured in Windows service recovery or systemd Restart= directive) provides resilience against crashes.

Security considerations include running with minimal necessary privileges (principle of least privilege), validating all input even from trusted sources, protecting sensitive data in configuration files and memory, and implementing proper authentication and authorization for any exposed interfaces. Services running with elevated privileges are attractive attack targets and must be hardened accordingly.

Service Management in Distributed Systems

Modern distributed systems and cloud environments introduce additional complexity in service management across multiple machines.

Container orchestration platforms like Kubernetes manage services across clusters of machines. Kubernetes Deployments define desired service state (how many replicas, what container image, resource requirements), and Kubernetes continuously works to maintain that state, automatically restarting failed containers, distributing load across nodes, and scaling services up or down. While these containerized applications aren’t “services” in the traditional OS sense, they serve the same architectural purpose—long-running background processes providing functionality.

Service discovery mechanisms allow services to find each other dynamically in distributed systems. When a web service needs to connect to a database service, it can’t use a hardcoded hostname because database instances might be added, removed, or moved. Service discovery systems like Consul, etcd, or Kubernetes Service objects maintain registries of available services with their current locations, and services query these registries to find dependencies.

Health checking monitors service availability and functionality. Platforms periodically probe services using HTTP health check endpoints, TCP connection attempts, or custom health check scripts. Unhealthy services can be automatically restarted, removed from load balancer pools, or flagged for administrator attention. Health checks detect not just crashed services but also services that are running but not functioning correctly.

Load balancing distributes traffic among multiple instances of a service. When you have three web server instances providing the same service, a load balancer directs incoming requests to all three, spreading load evenly. If one instance fails health checks, the load balancer stops sending it traffic while the orchestration platform attempts to recover or replace it.

Service mesh architectures like Istio or Linkerd inject proxy sidecars alongside application services, handling cross-service communication, implementing circuit breakers, retry logic, mutual TLS authentication, and distributed tracing. This approach moves networking concerns out of application code into infrastructure, making services simpler and more reliable.

Configuration management in distributed environments often uses centralized configuration services like Consul, etcd, or cloud provider configuration services. Services retrieve configuration from these systems at startup or watch for configuration changes, allowing centralized configuration updates across many service instances without redeploying.

Monitoring and observability for distributed services requires correlating logs, metrics, and traces across multiple instances and services. Tools like Prometheus (metrics), ELK stack (logs), and Jaeger (distributed tracing) provide visibility into distributed service behavior, essential for troubleshooting problems that span multiple services or nodes.

Troubleshooting Service Problems

When services fail to start, crash, or misbehave, systematic troubleshooting procedures identify and resolve issues.

Service won’t start is a common problem. Check the service status output for error messages—”systemctl status servicename” shows recent log output on Linux, Windows Event Viewer contains service startup errors. Common causes include configuration errors (invalid paths, syntax errors), missing dependencies (required services not running or files not found), permission problems (service account lacks access to required resources), or port conflicts (another process already using the service’s network port).

Service crashes or stops unexpectedly. Examine crash dumps on Windows or core dumps on Linux for crash analysis. Review service logs around the crash time—many services log fatal errors before terminating. Check system resources—out of memory, disk space exhaustion, or resource limit hits can cause crashes. Look for recent system changes—updates, configuration modifications, or deployments that might have introduced bugs.

Service responds slowly or becomes unresponsive. This might indicate resource exhaustion (high CPU, memory leaks, disk I/O saturation), dependency problems (waiting for unresponsive backend services or database), or deadlocks within the service. Performance monitoring tools reveal resource bottlenecks. Thread dumps or process traces show what the service is doing internally.

Permissions and access denied errors commonly prevent service operation. Services running under restrictive accounts might lack access to required files, network resources, or system capabilities. On Windows, running services under LocalService or NetworkService provides minimal permissions—upgrading to LocalSystem or custom accounts with appropriate permissions might be necessary. On Linux, services running as unprivileged users need appropriate file permissions, capabilities (like CAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE for binding privileged ports), or SELinux policies.

Dependency problems occur when required services aren’t running or start in wrong order. Review service dependencies and ensure prerequisites are configured correctly. Circular dependencies prevent any service in the cycle from starting and must be resolved by breaking the cycle.

Port conflicts arise when multiple services attempt to bind the same network port. The netstat or ss command shows which process is using which port. Change port configuration for one service or stop the conflicting service.

Service fails after system updates. Updates might change configuration file formats, introduce incompatibilities, or modify default settings. Review update logs and release notes for the updated components. Check configuration files for deprecation warnings or required format changes.

Security Considerations for Services

Services often run with elevated privileges and face network exposure, making security critical.

Principle of least privilege dictates running services with minimum necessary permissions. Don’t run services as root/SYS.TEM unless absolutely required. Create dedicated service accounts with only permissions needed for the service’s functions. On Linux, use capabilities to grant specific privileges without full root access.

Service hardening includes several practices. Disable unnecessary services—every running service is potential attack surface. Configure firewalls to restrict which hosts can connect to service ports. Use SELinux or AppArmor to confine service behavior within security policies. Enable service-specific security features like PHP safe_mode, MySQL privilege restrictions, or Apache security modules.

Authentication and authorization protect service access. Services exposing network interfaces should require authentication, use strong encryption (TLS/SSL), validate all input to prevent injection attacks, and implement rate limiting to prevent denial-of-service attacks.

Regular updates patch security vulnerabilities. Services, particularly those facing the internet, must be kept updated. Subscribe to security mailing lists for critical services, monitor for security advisories, and apply patches promptly.

Service monitoring detects suspicious behavior. Log failed authentication attempts, monitor for unusual access patterns or traffic volumes, and alert on service crashes or restarts that might indicate exploitation attempts.

Secrets management ensures services access credentials securely. Avoid hardcoding passwords in configuration files. Use secret management systems like HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, or Kubernetes Secrets to store and access sensitive credentials with encryption and access controls.

Conclusion

Services and daemons represent the silent workforce of modern operating systems, running continuously in the background to provide essential functionality, respond to events, and maintain operations without requiring user presence or intervention. From the web servers hosting websites to the database engines managing data, from the security services protecting systems to the networking daemons maintaining connectivity, these background processes form the foundation upon which our computing infrastructure operates. Understanding what services and daemons are, how they’re managed across different operating systems, what common services do, and how to control and troubleshoot them provides essential knowledge for anyone working with computers beyond basic casual use.

The evolution from simple background processes requiring manual management to sophisticated service management systems like systemd, launchd, and Windows Service Control Manager reflects the increasing complexity and reliability requirements of modern computing. Today’s service managers handle dependency resolution, automatic restart on failure, resource limitation, security confinement, and integration with monitoring systems—capabilities that would have been unimaginable to early Unix daemon developers. As computing continues evolving toward distributed systems, containers, and cloud-native architectures, the concept of services adapts and extends, with container orchestration platforms like Kubernetes essentially reimplementing service management at cluster scale with concepts directly descended from traditional OS services.

Whether you’re a system administrator managing servers, a developer building applications that depend on background services, a DevOps engineer deploying containerized workloads, or a curious user wanting to understand what’s running on your computer, comprehending services and daemons is fundamental to understanding modern computing. These persistent background processes enable the “always-on” functionality we’ve come to expect—email servers that receive mail 24/7, backup systems that protect our data automatically, monitoring services that alert us to problems before they become critical, and countless other capabilities that make computers reliable, useful tools rather than just interactive calculators. The next time you notice your computer responding to network requests, maintaining synchronized time, or performing scheduled maintenance tasks, you’re witnessing services and daemons at work—the invisible infrastructure that transforms raw computing hardware into a useful, reliable system.

Summary Table: Services and Daemons Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows Services | Linux systemd | Linux SysV Init | macOS launchd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Manager | Service Control Manager (SCM) | systemd | init + rc scripts | launchd |

| Configuration Location | Registry:<br>HKLM\SYSTEM\Current.ControlSet\Services | Unit files:<br>/etc/sys.temd/system/<br>/lib/sys.temd/system/ | Scripts:<br>/etc/in.it.d/ | Property lists:<br>/Library/Launch.Daemons/<br>/Library/Launch.Agents/ |

| Configuration Format | Registry entries | INI-style unit files | Shell scripts | XML plist files |

| Primary Management Tool | services.msc (GUI)<br>s.c.exe (CLI)<br>Power.Shell cmdlets | systemctl | service command<br>/etc/in.it.d/ scripts | launchctl |

| Auto-Start Configuration | Automatic, Automatic (Delayed), Manual, Disabled | systemctl enable/disable | update-rc.d or chk.config | launchctl lo.ad/unload |

| Dependency Management | Dependency list in service config | Requires=, Wants=, After=, Before= | Defined in init scripts | KeepAlive, dependencies in plist |

| Start Command | sc start Service.Name<br>Start-Service | systemctl start servicename | service servicename start<br>/etc/in.it.d/service.name start | launchctl start label |

| Stop Command | sc stop Service.Name<br>Stop-Service | systemctl stop servicename | service servicename stop<br>/etc/in.it.d/service.name stop | launchctl stop label |

| Status Check | sc query Service.Name<br>Get-Service | systemctl status servicename | service servicename status<br>/etc/in.it.d/service.name status | launchctl list |

| Service Accounts | LocalSystem, LocalService, NetworkService, custom accounts | User=, Group= in unit file | Specified in init script | UserName in plist |

| Logging Integration | Windows Event Log | systemd journal (journalctl) | syslog | syslog or file-based |

| Restart on Failure | Recovery actions in service properties | Restart= directive in unit file | Must be scripted manually | KeepAlive in plist |

| Resource Limits | Job Objects (limited exposure) | MemoryLimit=, CPUQuota=, etc. | ulimit in scripts | ResourceLimits in plist |

| Parallel Startup | Limited parallelization | Extensive parallelization based on dependencies | Sequential by runlevel order | Event-driven, some parallelization |

| Socket Activation | Not natively supported | Native socket activation | Not supported | Socket activation via LaunchSockets |

Common Service/Daemon Examples:

| Service/Daemon | Windows Name | Linux Name | macOS Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web Server | IIS (World Wide Web Publishing Service) | httpd/apache2 or nginx | httpd or nginx | Serve web content over HTTP/HTTPS |

| SSH Server | OpenSSH Server (sshd) | sshd | sshd | Secure remote shell access |

| DNS Server | DNS Server | named/bind9 | named | Domain name resolution |

| Database | MSSQL Server | mysqld, postgresql | mysqld, postgresql | Database management |

| Print Spooler | Print Spooler (spoolsv.exe) | cupsd | cupsd | Manage print jobs |

| Task Scheduler | Task Scheduler | crond | launchd | Execute scheduled tasks |

| Network Time | Windows Time | chronyd/ntpd | ntpd/timed | Time synchronization |

| Firewall | Windows Firewall | firewalld/ufw | pf (packet filter) | Network packet filtering |

| System Logging | Windows Event Log | rsyslogd/journald | syslogd | Collect and store system logs |

| Network Manager | Network Service | NetworkManager/systemd-networkd | networkd | Manage network connections |