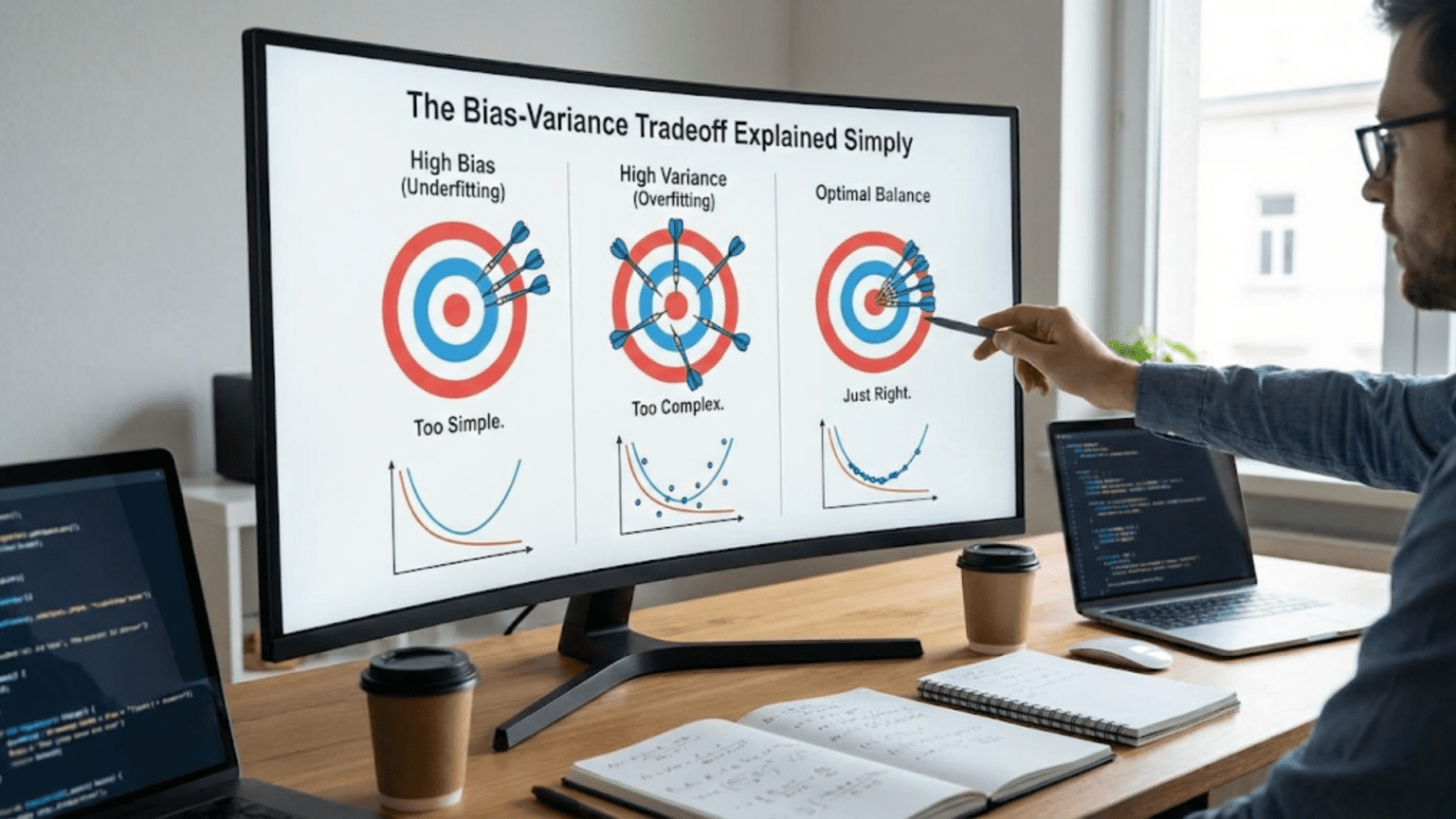

The bias-variance tradeoff is the fundamental tension in machine learning between two sources of error: bias (error from overly simplistic assumptions causing underfitting) and variance (error from excessive sensitivity to training data causing overfitting). High bias models are too simple and miss patterns, while high variance models are too complex and memorize noise. The sweet spot minimizes total error by balancing both—models complex enough to capture patterns but simple enough to generalize to new data.

Introduction: The Fundamental Dilemma

Imagine you’re trying to hit a target with darts. You throw many darts and observe two different patterns of misses. In the first pattern, all your darts cluster tightly together, but they’re consistently off-center—they’re precise but inaccurate. In the second pattern, your darts scatter widely around the target—sometimes close, sometimes far, but averaging near the center. Which is better? Neither is ideal. You want darts that cluster tightly AND center on the target.

Machine learning faces exactly this challenge. The bias-variance tradeoff is the formal description of why getting good predictions is so difficult. It explains why simple models often fail, why complex models also fail, and why finding the right balance is the core challenge of machine learning.

Bias and variance aren’t just abstract statistical concepts—they’re the two fundamental sources of prediction error that you’re constantly fighting when building models. Understanding this tradeoff transforms how you think about model selection, why certain approaches work, and how to diagnose and fix poor performance.

Every decision you make in machine learning—choosing algorithms, selecting features, tuning hyperparameters, regularizing models—is ultimately about navigating the bias-variance tradeoff. Too much bias and your model is too simple, missing important patterns in the data. Too much variance and your model is too complex, learning noise instead of signal.

This comprehensive guide explains the bias-variance tradeoff from the ground up. You’ll learn what bias and variance are, how they contribute to error, why they work against each other, how to diagnose which you’re suffering from, and practical strategies to find the optimal balance. With clear explanations, visual examples, and real-world applications, you’ll develop the intuition to navigate this fundamental machine learning challenge.

Understanding Error: The Components

Before understanding bias and variance, we need to understand prediction error.

Total Error Decomposition

Prediction Error on a new example has three components:

Total Error = Bias² + Variance + Irreducible ErrorIrreducible Error (also called noise):

- Inherent randomness in the problem

- Cannot be reduced no matter how good your model

- From measurement errors, unmeasured factors, true randomness

- Example: Predicting tomorrow’s weather—some uncertainty is fundamental

Reducible Error: Bias² + Variance

- Can be improved through better modeling

- This is what we focus on

The Tradeoff:

- Reducing bias often increases variance

- Reducing variance often increases bias

- Must balance both to minimize total error

What is Bias? The Underfitting Error

Bias is the error from overly simplistic assumptions in the learning algorithm. It represents how far off the model’s average predictions are from the true values.

Conceptual Understanding

High Bias Model:

- Makes strong assumptions about data

- Too simple to capture true patterns

- Systematically wrong in the same direction

- Underfits the data

Analogy: Using a ruler to trace a circle

- The ruler (linear model) is fundamentally too limited

- No matter how carefully you try, you can’t capture the curve

- You’ll consistently miss the true shape

Visual Example

True Relationship: Quadratic curve (y = x²)

High Bias Model: Straight line (y = mx + b)

True curve: /‾‾‾\

| |

/ \

Linear fit: /

/

/

Systematic error: Line can't capture curveEven with infinite training data, the line can’t fit the curve. This is bias.

Mathematical Understanding

Bias: Expected difference between model’s predictions and true values

Where:

- f̂(x) = model’s prediction

- f(x) = true value

- E[…] = expected value (average across many training sets)

High Bias: Model consistently predicts too high or too low

Example:

True value: 100

Model's predictions across different training sets:

Training set 1: 75

Training set 2: 73

Training set 3: 76

Training set 4: 74

Average: 74.5

Bias = 74.5 - 100 = -25.5 (consistently underestimates)Characteristics of High Bias

Performance Pattern:

- Poor training performance

- Poor test performance

- Similar errors on both training and test

- Underfitting

Model Characteristics:

- Too simple

- Too few parameters

- Strong assumptions

- High regularization

Examples:

- Linear regression for non-linear relationship

- Shallow decision tree for complex decision boundaries

- Naive Bayes assuming feature independence when features are highly correlated

- Small neural network for complex image recognition

Causes of High Bias

- Model too simple: Lacks capacity to represent true relationship

- Insufficient features: Missing important information

- Over-regularization: Penalty too strong, forcing model too simple

- Wrong assumptions: Model assumes patterns that don’t exist

Real-World Example: House Price Prediction

Scenario: Predicting house prices

High Bias Approach: Linear model with only one feature (square footage)

Price = 150 × sqft + 50,000Problem: Ignores location, condition, age, etc.

Result:

- Beach house: Predicts $500k, Actually $2M (underestimates)

- Rural house: Predicts $500k, Actually $200k (overestimates)

- Systematic errors because model too simple

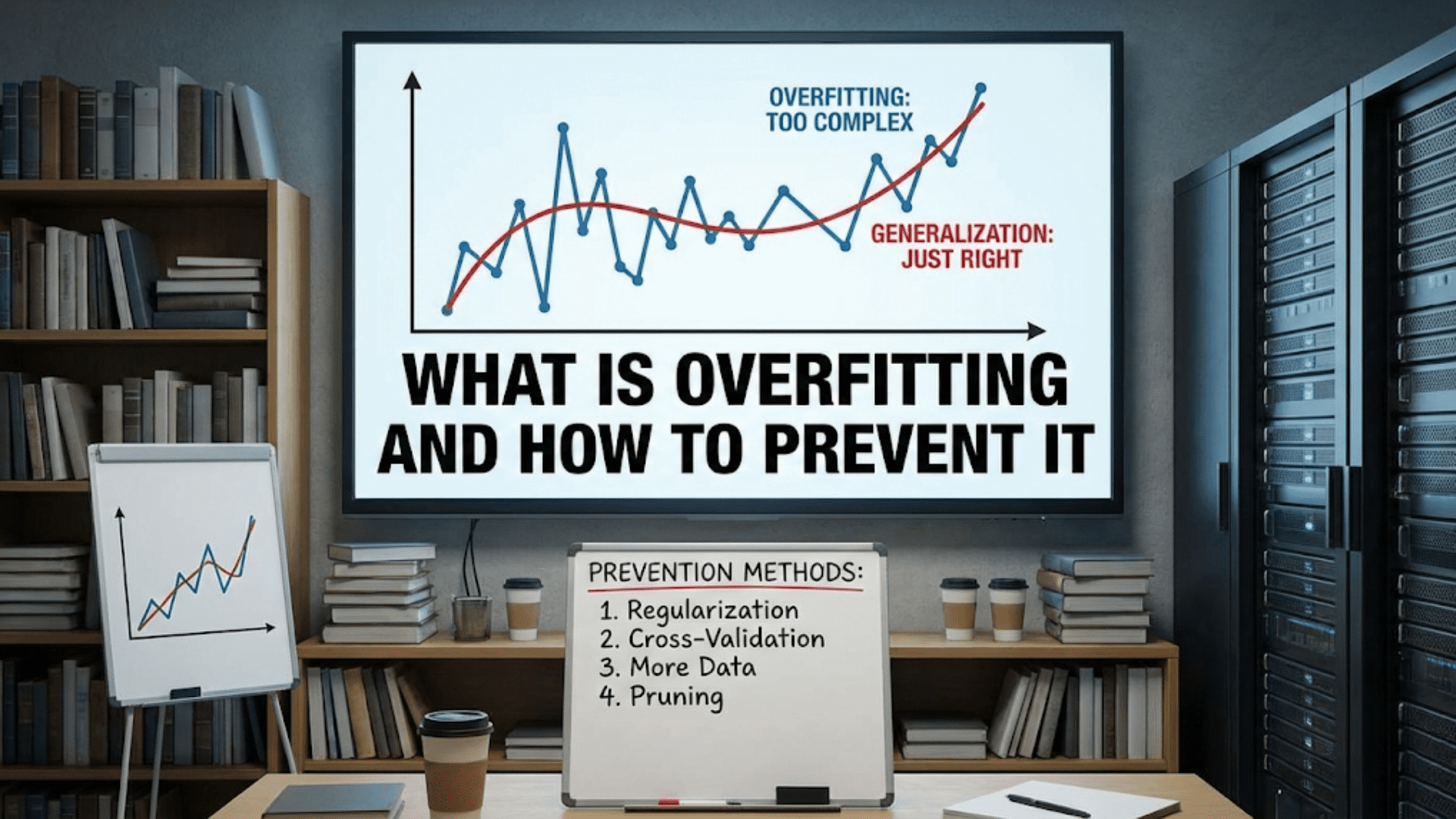

What is Variance? The Overfitting Error

Variance is the error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in training data. It represents how much model predictions vary when trained on different datasets.

Conceptual Understanding

High Variance Model:

- Very flexible, few constraints

- Too complex, fits noise

- Changes dramatically with different training data

- Overfits the data

Analogy: Memorizing exam questions

- Student memorizes specific practice problems

- Changes completely with different practice set

- Doesn’t learn generalizable concepts

- Fails on actual exam with different questions

Visual Example

True Relationship: Smooth curve with noise

High Variance Model: Wiggly curve fitting every point

Training data: • • • • • • •

High variance: \_/\__/\/\_/\/

(fits every point, including noise)

New data: • • • • •

Same model: \_/\__/\/\_/\/

(terrible fit—learned noise not pattern)Mathematical Understanding

Variance: How much predictions vary across different training sets

Variance = E[(f̂(x) – E[f̂(x)])²]

High Variance: Predictions change dramatically with different training data

Example:

True value: 100

Model's predictions for same input across different training sets:

Training set 1: 120

Training set 2: 85

Training set 3: 135

Training set 4: 70

Average: 102.5 (close to true value)

But huge spread! Variance = E[(prediction - 102.5)²]

= (400 + 306.25 + 1056.25 + 1056.25) / 4 = 704.7

Model predictions are all over the placeCharacteristics of High Variance

Performance Pattern:

- Excellent training performance

- Poor test performance

- Large gap between training and test error

- Overfitting

Model Characteristics:

- Too complex

- Too many parameters

- Few assumptions

- Little/no regularization

Examples:

- High-degree polynomial regression

- Deep decision tree with no pruning

- Neural network with millions of parameters trained on thousands of examples

- k-NN with k=1 (nearest neighbor is always training point itself)

Causes of High Variance

- Model too complex: Too many parameters relative to data

- Insufficient training data: Can’t constrain complex model

- No regularization: Nothing prevents overfitting

- Training too long: Continues learning noise after patterns

Real-World Example: House Price Prediction

Scenario: Same house price prediction

High Variance Approach: 20th-degree polynomial with all possible feature interactions, tiny dataset (50 houses)

Problem: Model memorizes training houses exactly

Result:

- Training houses: Perfect predictions (zero error)

- New houses: Terrible predictions

- Small change in training data completely changes model

The Tradeoff: Why You Can’t Have Both Low

The fundamental challenge: reducing one increases the other.

The Seesaw Relationship

Complexity → Simple ..................... Complex

Bias → High ....................... Low

Variance → Low ........................ HighSimple Models:

- High bias (can’t capture patterns)

- Low variance (consistent predictions)

Complex Models:

- Low bias (can capture patterns)

- High variance (unstable predictions)

Why the Tradeoff Exists

Increasing Model Complexity:

Effect on Bias:

- More flexible model can fit true patterns better

- Fewer assumptions

- Bias decreases ↓

Effect on Variance:

- More parameters to tune from data

- More ways to fit noise

- More sensitive to training set specifics

- Variance increases ↑

Example:

Polynomial degree 1 (linear):

- Bias: High (can't fit curves)

- Variance: Low (stable line)

Polynomial degree 20:

- Bias: Low (can fit any curve)

- Variance: High (wiggly, unstable)The Sweet Spot

Optimal Complexity: Minimizes total error (bias² + variance)

Total Error

High │ \

│ \ /

│ \__________/

│ / \

Low │ / \

│____/________________\____

Simple Complex

↑

Sweet SpotLeft of Optimal: High bias dominates (underfitting) Right of Optimal: High variance dominates (overfitting) Optimal Point: Best balance, lowest total error

Practical Manifestation

Training Error:

Simple → Complex: High → Medium → Low → Very Low

(Decreases monotonically)Test Error:

Simple → Complex: High → Medium → Low → High again

(U-shaped curve)

↓

Sweet spotAt Sweet Spot:

- Training error: Moderate (not perfect)

- Test error: Minimized

- Small gap between training and test

- Best generalization

Diagnosing Bias vs. Variance Problems

How do you know which problem you have?

Diagnostic Framework

Check Training Performance:

Training Error High → High Bias Problem

Training Error Low → Potential Variance ProblemCheck Gap Between Training and Test:

Small Gap → Likely High Bias

Large Gap → Likely High VarianceFour Scenarios

Scenario 1: High Bias (Underfitting)

Symptoms:

Training Error: High (e.g., 30%)

Test Error: High (e.g., 32%)

Gap: Small (2%)Diagnosis: High bias, model too simple

Evidence: Can’t even fit training data well

Solution Direction: Increase complexity

Scenario 2: High Variance (Overfitting)

Symptoms:

Training Error: Very Low (e.g., 2%)

Test Error: High (e.g., 25%)

Gap: Large (23%)Diagnosis: High variance, model too complex

Evidence: Excellent on training, poor on test

Solution Direction: Reduce complexity or get more data

Scenario 3: High Bias AND High Variance

Symptoms:

Training Error: Moderate (e.g., 15%)

Test Error: High (e.g., 30%)

Gap: Large (15%)Diagnosis: Both problems

Evidence:

- Moderate training error (bias)

- Large gap (variance)

Solution: Tricky! Need to address both

Scenario 4: Good Balance (Sweet Spot)

Symptoms:

Training Error: Low-Moderate (e.g., 5%)

Test Error: Low-Moderate (e.g., 7%)

Gap: Small (2%)Diagnosis: Well-balanced model

Evidence: Good performance, small gap

Action: Deploy!

Diagnostic Table

| Training Error | Test Error | Gap | Diagnosis | Primary Issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | High | Small | Underfitting | High Bias |

| Low | Low | Small | Good Fit | Balanced |

| Very Low | High | Large | Overfitting | High Variance |

| Moderate | High | Large | Mixed | Both Bias & Variance |

Fixing High Bias: Reducing Underfitting

When diagnosis reveals high bias, increase model capacity.

Strategy 1: Increase Model Complexity

Actions:

For Neural Networks:

- Add more layers

- Add more neurons per layer

- Use more complex architectures

For Decision Trees:

- Allow deeper trees

- Reduce min_samples_split

- Reduce min_samples_leaf

For Polynomial Regression:

- Increase polynomial degree

Example:

# Before (high bias)

model = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=3)

Training: 72%, Test: 70% (both poor)

# After (increase complexity)

model = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=10)

Training: 85%, Test: 83% (both better)Strategy 2: Add More Features

Feature Engineering:

- Create interaction features

- Add polynomial features

- Engineer domain-specific features

- Include more raw features

Example:

# Before (3 features)

Features: [square_feet, bedrooms, bathrooms]

Accuracy: 70%

# After (10 features)

Features: [square_feet, bedrooms, bathrooms,

location, age, condition, garage,

square_feet × location,

age × condition]

Accuracy: 82%Strategy 3: Reduce Regularization

Decrease Regularization Strength:

# Before (strong regularization)

model = Ridge(alpha=100) # High penalty

# After (reduce penalty)

model = Ridge(alpha=0.1) # Lower penaltyReduce Dropout:

# Before (high dropout)

model.add(Dropout(0.8)) # Drops 80% of neurons

# After (reduce dropout)

model.add(Dropout(0.3)) # Drops only 30%Strategy 4: Train Longer

For iterative algorithms:

- Increase number of epochs

- Train until convergence

Example:

# Before (stopped too early)

model.fit(X, y, epochs=10)

# After (train longer)

model.fit(X, y, epochs=100)Strategy 5: Try Different Algorithm

Move to More Flexible Algorithm:

Linear Regression → Polynomial Regression

Logistic Regression → Random Forest

Shallow Neural Net → Deep Neural NetFixing High Variance: Reducing Overfitting

When diagnosis reveals high variance, reduce model sensitivity.

Strategy 1: Get More Training Data

Most Effective Solution:

- Collect more labeled examples

- Data augmentation (images, text)

- Synthetic data generation

Why It Works:

- More data harder to memorize

- Noise averages out

- True patterns become clearer

Example:

1,000 examples: Train=98%, Test=75% (overfit)

10,000 examples: Train=92%, Test=88% (better)

100,000 examples: Train=90%, Test=89% (excellent)Strategy 2: Reduce Model Complexity

Actions:

Neural Networks:

- Fewer layers

- Fewer neurons per layer

- Simpler architectures

Decision Trees:

- Limit max depth

- Increase min_samples_split

- Prune tree

Polynomial Regression:

- Reduce polynomial degree

Example:

# Before (too complex)

model = RandomForestClassifier(max_depth=None, min_samples_split=2)

Train: 98%, Test: 72%

# After (reduce complexity)

model = RandomForestClassifier(max_depth=10, min_samples_split=10)

Train: 88%, Test: 85%Strategy 3: Add Regularization

L1/L2 Regularization:

# Add regularization

model = Ridge(alpha=10) # L2

model = Lasso(alpha=0.1) # L1Dropout (Neural Networks):

model.add(Dense(128))

model.add(Dropout(0.5)) # RegularizationEarly Stopping:

early_stop = EarlyStopping(monitor='val_loss', patience=10)

model.fit(X, y, validation_data=(X_val, y_val), callbacks=[early_stop])Strategy 4: Feature Selection

Remove Irrelevant Features:

- Use feature importance

- Correlation analysis

- Recursive feature elimination

Example:

# Before (100 features, many irrelevant)

Train: 95%, Test: 70%

# After (20 most important features)

Train: 87%, Test: 84%Strategy 5: Ensemble Methods

Combine Multiple Models:

- Bagging (Random Forests) reduces variance

- Averaging predictions

- Each model overfits differently

Example:

# Single tree (high variance)

model = DecisionTreeClassifier()

Train: 100%, Test: 75%

# Random Forest (ensemble, lower variance)

model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100)

Train: 90%, Test: 86%Strategy 6: Cross-Validation

Use During Development:

- More robust performance estimates

- Less likely to overfit to validation set

Practical Example: Navigating the Tradeoff

Let’s walk through a complete example.

Problem Setup

Task: Predict customer churn Data: 5,000 customers, 30 features Baseline: Always predict “no churn” = 80% accuracy (naive)

Attempt 1: Logistic Regression (Too Simple)

Model: Simple logistic regression, 5 features

Results:

Training Accuracy: 81%

Test Accuracy: 80%

Gap: 1%Diagnosis:

- Both scores barely beat baseline

- Small gap

- High Bias: Model too simple

Evidence: Can’t even fit training data well

Attempt 2: Random Forest, No Limits (Too Complex)

Model: Random Forest with default settings (very deep trees)

Results:

Training Accuracy: 99%

Test Accuracy: 76%

Gap: 23%Diagnosis:

- Excellent training

- Poor test

- Large gap

- High Variance: Model overfitting

Evidence: Memorized training data

Attempt 3: Finding Balance

Systematic Approach: Try various complexities

Experiments:

max_depth=3: Train=82%, Test=81%, Gap=1% (still high bias)

max_depth=5: Train=85%, Test=84%, Gap=1% (better)

max_depth=7: Train=89%, Test=87%, Gap=2% (even better)

max_depth=10: Train=92%, Test=88%, Gap=4% (optimal!)

max_depth=15: Train=96%, Test=85%, Gap=11% (variance increasing)

max_depth=20: Train=98%, Test=82%, Gap=16% (high variance)

max_depth=None: Train=99%, Test=76%, Gap=23% (severe overfit)Optimal Choice: max_depth=10

- Training: 92% (good, not perfect)

- Test: 88% (best test performance)

- Gap: 4% (acceptable)

- Best bias-variance balance

Attempt 4: Further Optimization

Add Regularization to depth=10 model:

model = RandomForestClassifier(

max_depth=10,

min_samples_split=10, # Regularization

min_samples_leaf=5, # Regularization

n_estimators=100

)Results:

Training Accuracy: 90%

Test Accuracy: 89%

Gap: 1%

Analysis:

- Slightly lower training (90% vs 92%)

- Higher test (89% vs 88%)

- Smaller gap (1% vs 4%)

- Better generalization!

Learning Curves Analysis

Plot Training and Test Error vs. Model Complexity:

Error

High │ \ /

│ \ /

│ \____Test_______/

│ \ /

│ \____________/

Low │ \__Training_____

│__________________________

Simple Complex

↑

max_depth=10Observations:

- Left: High training AND test error (bias)

- Middle: Minimum test error (sweet spot)

- Right: Low training, high test error (variance)

Final Model

Configuration:

RandomForestClassifier(

max_depth=10,

min_samples_split=10,

min_samples_leaf=5,

n_estimators=100,

random_state=42

)Performance:

Training: 90%

Validation: 89%

Test: 88.5%Interpretation:

- Excellent test performance

- Small train-test gap

- Optimal bias-variance balance

- Ready for deployment

Advanced: Bias-Variance Decomposition

For regression, we can mathematically decompose error.

The Mathematics

For a point x with true value y:

Expected Error = Bias² + Variance + Noise

Where:

Bias² = (E[f̂(x)] - y)²

Variance = E[(f̂(x) - E[f̂(x)])²]

Noise = irreducible errorEmpirical Estimation

Process:

- Train many models on different training sets

- Make predictions on same test point

- Calculate bias and variance empirically

Example:

import numpy as np

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor

# True function: y = x²

def true_function(x):

return x**2

# Generate test point

x_test = 0.5

y_true = true_function(x_test)

# Train 100 models on different samples

predictions = []

for _ in range(100):

# Different random training set each time

X_train = np.random.uniform(-1, 1, 50).reshape(-1, 1)

y_train = true_function(X_train) + np.random.normal(0, 0.1, X_train.shape)

model = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_depth=5)

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

pred = model.predict([[x_test]])[0]

predictions.append(pred)

# Calculate components

mean_prediction = np.mean(predictions)

bias_squared = (mean_prediction - y_true)**2

variance = np.var(predictions)

mse = np.mean((predictions - y_true)**2)

print(f"Bias²: {bias_squared:.4f}")

print(f"Variance: {variance:.4f}")

print(f"MSE: {mse:.4f}")

print(f"Bias² + Variance: {bias_squared + variance:.4f}")Bias-Variance in Different Contexts

Classification

Bias: Systematic errors in class predictions

- High bias: Predicts wrong class consistently

- Example: Always predicts majority class

Variance: Prediction instability

- High variance: Class predictions change with training set

- Example: Decision boundary moves dramatically

Deep Learning

Bias:

- Network too small (few layers/neurons)

- Early stopping too aggressive

Variance:

- Network too large

- Training too long

- Insufficient data

Modern Trend: Deep networks with heavy regularization

- Large capacity (low bias potential)

- Regularization controls variance

- Best of both worlds

Ensemble Methods

Bagging (Random Forests): Reduces variance

- Train many high-variance models

- Average predictions

- Variance decreases, bias unchanged

Boosting: Reduces bias

- Sequentially train weak models

- Each corrects predecessor’s errors

- Bias decreases, some variance increase

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “More Data Always Helps”

Truth: More data helps HIGH VARIANCE, not high bias

Example:

High bias (linear model for curved data):

1,000 examples: 70% accuracy

1,000,000 examples: 71% accuracy (minimal improvement)

Model is fundamentally too simple

High variance (complex model):

1,000 examples: 75% accuracy

1,000,000 examples: 92% accuracy (huge improvement)

More data constrains overfittingMisconception 2: “Complex Models Always Better”

Truth: Only if you have enough data

Example:

100 examples:

Simple model: 80% accuracy

Complex model: 70% accuracy (overfits)

100,000 examples:

Simple model: 81% accuracy (bias-limited)

Complex model: 92% accuracy (has data to learn)Misconception 3: “Zero Training Error is Good”

Truth: Zero training error usually means overfitting (high variance)

Healthy Model: Some training error acceptable

- Indicates model not memorizing

- Generalization capacity preserved

Misconception 4: “Regularization Always Helps”

Truth: Regularization helps high variance, hurts high bias

Too Much Regularization:

Causes: High bias (over-regularized)

Training error: High

Test error: High

Both are badBest Practices for Managing Bias-Variance Tradeoff

During Development

- Start Simple: Begin with simple model, increase complexity gradually

- Plot Learning Curves: Visualize train/test error vs. complexity

- Diagnose First: Identify whether bias or variance is the problem

- Apply Appropriate Fix: Don’t blindly add complexity or data

Model Selection

- Cross-Validation: Get robust estimates across multiple splits

- Multiple Metrics: Don’t rely on single number

- Validation Curve: Plot performance vs. hyperparameter values

- Learning Curve: Plot performance vs. training set size

Deployment

- Monitor Both Metrics: Track training and test/production performance

- Watch for Drift: Performance degradation signals changing patterns

- Retrain Periodically: Update with fresh data to maintain balance

Comparison: Strategies for Bias vs. Variance

| Problem | Symptoms | Solutions | What NOT to Do |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Bias | Training & test errors both high, small gap | Increase complexity, add features, reduce regularization, train longer | Add more data (won’t help much), increase regularization |

| High Variance | Training error low, test error high, large gap | Get more data, reduce complexity, add regularization, feature selection | Increase complexity, reduce regularization |

| Good Balance | Both errors acceptable, small gap | Maintain current approach, monitor | Over-optimize (risk breaking balance) |

| Both Issues | Moderate training error, high test error, large gap | Carefully add complexity AND data, neural nets with regularization | Simple solutions (need nuanced approach) |

Conclusion: The Central Challenge of Machine Learning

The bias-variance tradeoff isn’t just a theoretical concept—it’s the fundamental challenge underlying all of machine learning. Every time you adjust model complexity, select features, tune hyperparameters, or choose algorithms, you’re navigating this tradeoff.

Understanding bias and variance transforms how you approach machine learning:

Bias is error from oversimplification. High bias models make strong assumptions, miss patterns, and underfit. They’re consistently wrong, failing on both training and test data.

Variance is error from overcomplexity. High variance models are too sensitive to training data specifics, learn noise, and overfit. They excel on training data but fail to generalize.

The tradeoff exists because reducing one increases the other. Simple models have high bias but low variance. Complex models have low bias but high variance. The sweet spot balances both, minimizing total error.

Diagnosis is key. Look at training and test performance together:

- Both poor → high bias

- Training great, test poor → high variance

- Both good → optimal balance

Solutions differ by problem:

- High bias → increase complexity, add features, reduce regularization

- High variance → get more data, reduce complexity, add regularization

The goal isn’t eliminating bias and variance—it’s finding the right balance for your specific problem, data, and constraints. Sometimes you’ll accept higher bias for lower variance, or vice versa, depending on what matters for your application.

As you build machine learning systems, make bias-variance analysis a core part of your workflow. Plot learning curves. Diagnose which error dominates. Apply targeted solutions. Monitor the balance in production. This disciplined approach to managing the bias-variance tradeoff is what separates effective machine learning practitioners from those who struggle.

Master this fundamental tradeoff, and you’ve mastered the essence of machine learning—finding models that capture genuine patterns without memorizing noise, delivering robust performance on new data rather than just impressive numbers on training sets.