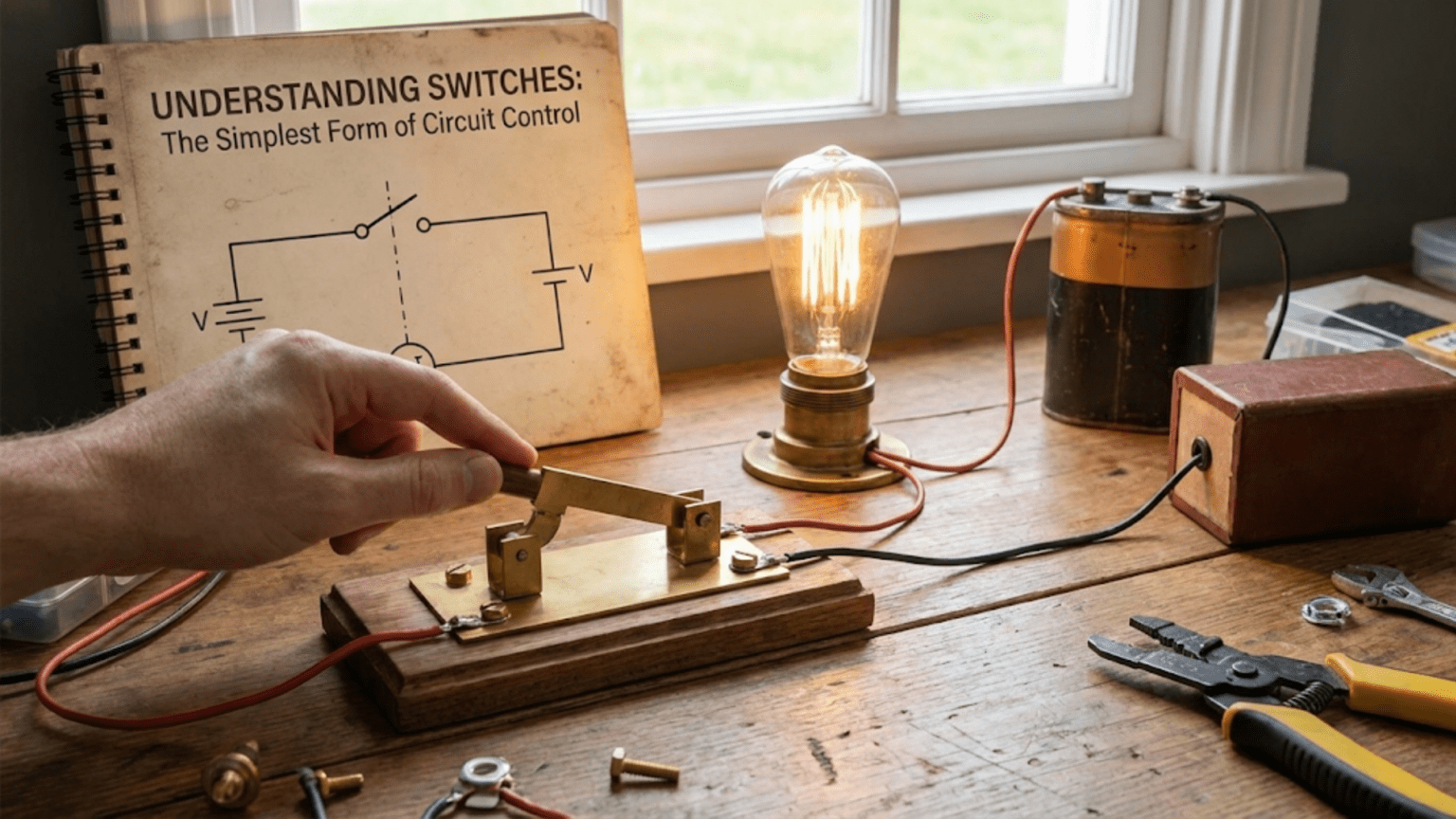

Introduction: The Power of Control

Imagine if every electrical device in your home was permanently on. Lights would burn continuously, draining power and wearing out bulbs. Your refrigerator would run without pause. Your television would blare endlessly. This absurd scenario highlights something we take utterly for granted: the ability to control when electricity flows and when it doesn’t. That control, in its most fundamental form, comes from switches.

A switch is perhaps the simplest component in all of electronics, yet it’s also one of the most essential. In its purest form, a switch is just a controllable break in a circuit. When the switch is closed, current flows freely through it as if it were a piece of wire. When the switch is open, current cannot flow, and the circuit is broken. This binary nature, this on-or-off control, is so fundamental that it forms the basis not just of electrical circuits but of digital computing itself.

But don’t let this simplicity fool you. Understanding switches deeply reveals profound insights about circuits, control systems, and even the nature of digital information. Why do some switches have two positions while others have three or more? What makes a momentary switch different from a latching switch? How do you read switch specifications and choose the right switch for your application? What is contact bounce and why does it matter? And how did this simple mechanical device evolve into the billions of transistor switches inside modern microprocessors?

In this comprehensive guide, we’re going to explore switches from every angle. We’ll start with the fundamental principle of making and breaking electrical connections. We’ll examine the many types of switches and their applications. We’ll discuss electrical ratings and why they matter. We’ll explore switch configurations and how to read their specifications. We’ll address practical considerations like contact bounce and noise. And we’ll see how this simple component connects to broader themes in electronics and computing. By the end, you’ll have a complete understanding of switches and the critical role they play in controlling electricity.

The Fundamental Principle: Making and Breaking Connections

To truly understand switches, we need to start at the most basic level: what it means to make or break an electrical connection and why this matters in circuits.

Circuits Require Complete Paths

As we’ve learned in previous articles, electric current only flows when there’s a complete circuit, a continuous path from the power source’s positive terminal, through components, and back to the negative terminal. Break that path anywhere, and current stops flowing throughout the entire circuit. This is fundamental to how electricity works and it’s why switches are so effective at controlling electrical devices.

Think of a circuit like a circular road where cars drive continuously. If you dig a trench across the road anywhere, cars cannot complete the loop and traffic stops everywhere. The circuit is like that road, and current is like the traffic. The switch is your controlled trench that you can dig and fill at will, stopping and starting traffic on command.

When you turn on a light switch, you’re not controlling the light bulb directly. You’re completing a circuit that allows current to flow from your electrical panel, through the wiring in your walls, through the light bulb’s filament, and back to the panel. The switch is simply connecting or disconnecting two wires, but this simple action controls the entire circuit because circuits require complete paths.

The Physical Mechanism of Switching

At the most basic level, a switch consists of conductive contacts that can be mechanically moved to touch each other or separate from each other. When the contacts touch, electricity can flow through them because metal conducts electricity. When the contacts separate, even by a tiny distance, electricity cannot flow across the air gap because air is an excellent insulator at normal voltages.

This air gap is crucial. The distance doesn’t need to be large; for low-voltage circuits like the 5-volt or 12-volt circuits common in electronics, a gap of even a fraction of a millimeter is enough to prevent current flow. For higher voltage circuits like the 120-volt or 240-volt wiring in your home, larger gaps are needed to prevent arcing across the gap.

The beauty of this mechanical approach is its simplicity and reliability. There are no complex components, no semiconductor physics to understand, no failure modes beyond physical wear. A properly designed switch simply either connects two conductors or separates them. It’s binary, it’s reliable, and it’s been working this way since the earliest days of electrical systems.

What Happens When You Flip a Switch

Let’s follow the physics of what happens in the moment you flip a switch. Imagine a simple circuit with a battery, an LED, a current-limiting resistor, and a switch, all connected in series. Initially, the switch is open. The battery has voltage across its terminals, creating an electric field, but no current flows because the circuit is incomplete. The LED is dark. There’s no voltage drop across the resistor because no current flows through it.

Now you press the switch. The contacts inside begin to move together. As they get very close, even before they actually touch, the electric field between them becomes extremely strong. At some point, if the voltage is high enough, you might see a tiny spark as the air between the contacts temporarily breaks down and becomes conductive. This is why you sometimes see a small flash when flipping switches in dark rooms.

Then the contacts touch. Instantly, the circuit is complete. Current begins to flow, limited by the resistance in the circuit. Electrons that were previously stationary in the wires suddenly start moving, creating current. The LED lights up. The resistor begins to warm slightly as it dissipates power. The battery’s chemical reaction accelerates to supply the current. All of this happens essentially instantaneously from a human perspective, within microseconds of the contacts touching.

When you open the switch, the reverse happens. The contacts begin to separate. Current continues to flow as long as the contacts touch. The instant they separate, current stops. If the circuit contains inductive components like motors or relays, the sudden current change can cause a voltage spike, and you might see a more substantial spark as the arc tries to maintain current flow across the widening gap. Eventually, the gap becomes too large for the voltage to bridge, the arc extinguishes, and current stops completely.

The Critical Role of Contact Quality

The effectiveness of a switch depends entirely on the quality of the electrical contact when closed and the reliability of the insulation when open. When closed, good switches have very low resistance, ideally just a few milliohms, so they don’t significantly affect the circuit or waste power as heat. Poor contacts might have higher resistance due to oxidation, contamination, or poor mechanical contact, causing voltage drops across the switch and potential heating.

When open, good switches provide complete electrical isolation with resistance in the millions or billions of ohms. This ensures that no leakage current flows. Poor switches might have contamination across the contacts or insufficient gap distance, allowing tiny leakage currents that can cause problems in sensitive circuits.

This is why switch manufacturers pay careful attention to contact materials, contact geometry, and actuation mechanisms. The contacts need to close firmly with good pressure to ensure low resistance. They need to separate completely to ensure high isolation. And they need to do this reliably for thousands or millions of operations over the switch’s lifetime.

Types of Switches: A Diverse Family

The simple concept of making and breaking connections has spawned an enormous variety of switch types, each optimized for different applications and user interfaces. Understanding these types helps you select the right switch for your needs.

Momentary vs. Latching Switches

One of the most fundamental distinctions among switches is whether they’re momentary or latching. This difference determines how the switch responds to user input and fundamentally affects how it’s used in circuits.

A momentary switch, also called a momentary-contact switch, only maintains its switched state while you actively hold it in that position. The moment you release it, it springs back to its default state. Think of a doorbell button or a computer keyboard key. You press it and it’s closed, conducting electricity. You release it and it springs back open, stopping current flow. The switching action is temporary, existing only as long as you apply force.

Momentary switches are perfect for applications where you want the action to occur only while you’re actively controlling it. A car horn uses a momentary switch; you want the horn to sound only while you press the button, not to keep blaring after you release it. A computer mouse button is momentary; you want the click to register when you press it, but the mouse to return to normal when you release.

A latching switch, by contrast, maintains its state after you actuate it. Flip a latching switch to the on position and it stays on until you actively flip it back to off. The common wall light switch in your home is a latching switch. You flip it up to turn the light on, and it stays up, keeping the circuit closed, until you flip it down again. The switch remembers its state mechanically.

Latching switches are ideal for controlling devices that should stay in a particular state until you deliberately change them. Lights, power switches on equipment, mode selectors, and other applications where you want persistent state all use latching switches.

Some switches can actually function as either momentary or latching depending on their design and how they’re mechanically configured. Understanding which type you need is essential when selecting switches for your projects.

Single Pole vs. Multiple Pole

Another critical distinction is how many separate circuits the switch can control simultaneously. This is described by the switch’s pole count.

A single-pole switch controls one circuit. It has one pair of contacts that make and break one electrical connection. This is the simplest and most common configuration. When you flip the switch, you’re opening or closing one circuit, nothing more.

A double-pole switch controls two separate circuits simultaneously with one mechanical action. It has two completely isolated pairs of contacts that both operate together. When you flip the switch, both circuits open or close at the same time. This is useful when you need to control both the positive and negative wires of a circuit simultaneously, or when you want one switch action to affect two different circuits in tandem.

You can also find three-pole, four-pole, and even higher pole counts in specialized switches. Each pole controls an independent circuit, but all poles are actuated by the same mechanical action. These are common in industrial applications where complex switching sequences are needed.

The key insight is that poles represent independent circuits. A double-pole switch isn’t just a switch with two positions; it’s a switch that simultaneously controls two separate electrical paths. This distinction is crucial when reading switch specifications and designing circuits.

Throw Configurations: How Many Positions

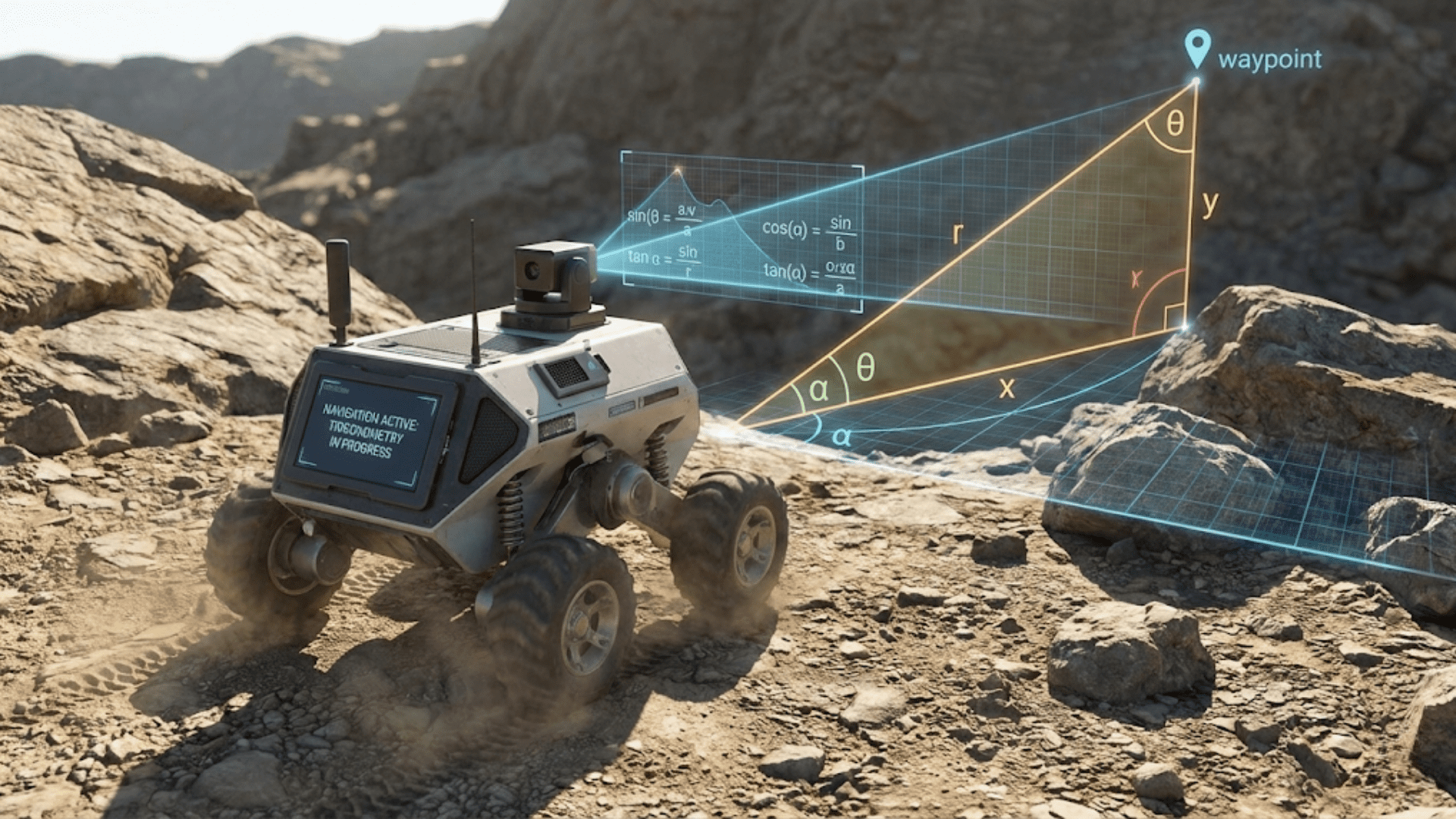

While poles describe how many circuits a switch controls, throws describe how many different connection states each pole can achieve. This determines the switch’s positional functionality.

A single-throw switch has only two states: connected or not connected. It makes or breaks one connection. A light switch is typically single-throw; it either completes the circuit or breaks it. There’s no third option.

A double-throw switch can connect a common terminal to either of two different terminals. Think of it as a selector that can route a connection to one of two places. A common example is a switch that can select between two different power sources, or that can switch a signal between two different circuits.

The double-throw configuration is incredibly useful for routing and selecting functions. You might use a double-throw switch to select between battery power and wall adapter power. You might use it to switch a speaker between two different audio sources. You might use it to reverse the polarity of a DC motor, making it run forwards or backwards.

You can combine poles and throws in various ways. A single-pole, single-throw switch, abbreviated SPST, is the simplest switch: one circuit, one connection to make or break. A single-pole, double-throw switch, abbreviated SPDT, controls one circuit but can route it to either of two destinations. A double-pole, single-throw switch, abbreviated DPST, controls two circuits simultaneously, each with a simple make-or-break action. A double-pole, double-throw switch, abbreviated DPDT, controls two circuits simultaneously, each with routing capability to two destinations.

These combinations allow switches to perform complex routing and control functions with simple mechanical actions. Understanding pole and throw configurations is essential for reading circuit diagrams and selecting appropriate switches for your needs.

Toggle, Rocker, Pushbutton, and Slide Switches

Beyond electrical configuration, switches differ in their physical form factor and actuation mechanism. The mechanical interface between human and switch varies widely based on application requirements.

Toggle switches have a lever that flips between positions, making a satisfying snap as internal spring mechanisms engage. These are the classic wall light switches in older homes, and they’re still common in applications ranging from aircraft control panels to electric guitars. Toggle switches provide clear tactile feedback; you can feel and hear when they change state. They’re available in both momentary and latching configurations, though latching is more common.

Rocker switches have a large panel that rocks back and forth on a central pivot. Press one side and it goes down while the other side comes up, like a seesaw. These are the modern standard for wall light switches in homes. They’re easy to operate even with a full hand or elbow, and they clearly show their state by which side is pressed down. Rocker switches are almost always latching.

Pushbutton switches are activated by pressing a button. The button might be large and easy to press, or small and flush-mounted. Pushbuttons can be momentary (like a doorbell) or latching (where you press once to turn on, press again to turn off). Pushbuttons are extremely common in user interfaces because they’re intuitive and can be arranged in arrays for multiple controls in small spaces.

Slide switches have a slider that moves linearly along a track. Miniature slide switches are very common in electronics because they’re small, reliable, and cheap. They’re usually latching and can have two, three, or more positions. You commonly see them on small electronic devices for power switching or mode selection.

Rotary switches turn through an arc or full circle, selecting between multiple positions. A simple rotary switch might have just two or three positions, while complex ones can have twelve or more positions arranged around a circle. These are ideal for selection functions like choosing between multiple inputs or adjusting settings with many discrete levels. Some rotary switches latch into each position while others rotate continuously like a volume knob.

Each of these form factors has advantages for particular applications. The choice depends on factors like available space, expected frequency of operation, need for tactile feedback, environmental conditions, and user interface requirements.

Special Purpose Switches

Beyond the common types, numerous specialized switches exist for specific applications. Understanding a few of these broadens your appreciation of how versatile the simple concept of switching can be.

Limit switches are designed to be actuated by mechanical contact with moving parts. They’re used extensively in machinery to detect when something has reached a certain position. A 3D printer uses limit switches to detect when the print head has reached the end of its travel. An elevator uses limit switches to know when it has reached a floor. These switches must be robust and reliable since they’re triggered by mechanical contact that might involve significant force.

Tilt switches contain a conductive ball or blob of mercury that rolls to make contact with terminals when the switch is tilted. These provide a simple way to detect orientation changes. Older thermostats used mercury tilt switches, and some simple leveling applications still use ball-type tilt switches. Mercury switches are being phased out due to environmental concerns, but the principle remains useful in various electronic tilt sensors.

Tactile switches are small pushbutton switches designed to provide clear tactile feedback. They’re used extensively in computer keyboards, game controllers, and electronic device buttons. The tactile bump you feel when pressing a key is often provided by a small tactile switch mechanism. These switches are designed for millions of operations and very precise feel.

Membrane switches are part of a flexible printed circuit that closes contacts when you press on a particular area. Many appliance control panels, microwave keypads, and remote controls use membrane switches because they can be made very thin, completely sealed against moisture, and printed with custom graphics. They’re inexpensive to manufacture in large quantities.

DIP switches are tiny arrays of switches in a package designed to fit into standard integrated circuit pin spacing. They’re used for configuration settings on circuit boards, allowing manual selection of options without requiring reprogramming. You often see them on older computer peripherals and electronic devices where occasional manual configuration is needed.

Each of these specialized types demonstrates how the fundamental concept of making and breaking connections can be adapted to specific needs with clever mechanical design.

Electrical Ratings: Choosing the Right Switch

Not all switches are created equal when it comes to how much voltage and current they can safely handle. Understanding switch ratings is crucial for selecting switches that will work reliably and safely in your applications.

Voltage Ratings Explained

Every switch has a maximum voltage rating, the highest voltage difference that can safely exist across the open switch contacts without causing breakdown. This rating reflects several physical realities about how electricity behaves.

When a switch is open, air or some other insulating material separates the contacts. Air is a good insulator at low voltages, but as voltage increases, the electric field strength between the contacts increases. At some voltage, the field becomes strong enough to ionize the air, making it conductive. This causes arcing across the gap, which can damage the switch contacts, weld them together, or create a fire hazard.

The exact voltage at which this occurs depends on the gap distance between contacts and the surrounding environment. A switch with contacts separated by one millimeter might be safe up to a few hundred volts. A switch with contacts separated by several millimeters might handle a thousand volts or more. Manufacturers test switches to determine their maximum safe voltage and rate them conservatively.

Voltage ratings are usually given for both AC and DC operation, and these can differ significantly. AC voltage constantly reverses polarity, which tends to extinguish arcs naturally as the voltage crosses through zero. DC voltage maintains constant polarity, making arcs more persistent. Because of this, switches typically have lower DC voltage ratings than AC voltage ratings. A switch rated for 250 volts AC might only be rated for 30 volts DC.

When selecting a switch, ensure its voltage rating exceeds the maximum voltage that will appear across it in your circuit. For safety-critical applications, use a significant margin. A switch rated for the exact voltage you need is at risk of failure; choosing a switch rated for at least twice your operating voltage provides a good safety margin.

Current Ratings and Why They Matter

In addition to voltage ratings, switches have maximum current ratings indicating how much current can flow through the closed switch without damaging it. This rating reflects the heating effects of current flowing through the contact resistance.

Even though a closed switch ideally has very low resistance, it’s never zero. A typical switch might have a contact resistance of 10 to 50 milliohms when new. When current flows through this resistance, power is dissipated as heat according to the formula P equals I squared times R. At low currents, this heating is negligible. At high currents, it can be significant.

Consider a switch with 20 milliohms contact resistance carrying 10 amps. The power dissipated is 10 squared times 0.02, which equals 2 watts. That might not sound like much, but concentrated in a small contact area, it can cause significant heating. The heat can oxidize the contacts, increasing resistance further, leading to more heating in a runaway cycle. Eventually, the contacts can weld together or burn out.

Current ratings account for this heating effect as well as the mechanical stress on contacts from magnetic forces when high currents flow. Manufacturers rate switches based on how much current the contacts can carry continuously without excessive heating or mechanical damage.

Like voltage ratings, current ratings often differ for AC and DC. AC current creates arcing as it reverses polarity, which can erode contacts faster than DC. But DC current can create stronger sustained arcs when switching. The ratings reflect these different stress mechanisms.

Always check both the continuous current rating (how much current the switch can carry steadily when closed) and the switching current rating (how much current can be flowing when you actually open or close the switch). These can differ significantly. A switch might be able to carry 10 amps continuously but only be rated to switch 5 amps without excessive arcing.

Resistive vs. Inductive Loads

Switch ratings often specify different values for resistive loads versus inductive or motor loads. This distinction is crucial for proper switch selection in motor control and other inductive circuit applications.

A resistive load, like a light bulb or heating element, presents a simple resistance to current flow. When you switch a resistive load, the current stops cleanly when you open the switch. There are no complicating factors beyond the basic voltage and current ratings.

An inductive load, like a motor, transformer, or relay coil, stores energy in a magnetic field. When you suddenly interrupt current through an inductor, the collapsing magnetic field induces a voltage spike that can be many times higher than the supply voltage. This spike can cause severe arcing across the switch contacts, rapidly eroding them and potentially welding them together.

Because of this, switches have significantly lower ratings for inductive loads than for resistive loads. A switch rated for 10 amps resistive might only be rated for 3 amps inductive. The reduced rating accounts for the additional stress from inductive kick during switching.

If you’re controlling motors, solenoids, relays, or other inductive loads, you must use the inductive load rating when selecting your switch. Alternatively, you can add snubber circuits across the inductive load to suppress the voltage spike, allowing you to use the higher resistive load rating. But never exceed the inductive rating without proper spike suppression.

Lifetime and Cycle Ratings

Switches don’t last forever. Every time you operate a switch, the mechanical action and electrical arcing cause small amounts of wear. Manufacturers specify an expected lifetime in terms of operating cycles, the number of times the switch can be operated before failure is likely.

For manual switches operated by humans, lifetimes are typically specified in thousands or tens of thousands of cycles. A toggle switch might be rated for 10,000 cycles. For switches operated frequently, this matters. If you use a switch once per day, 10,000 cycles means it should last about 27 years. If you use it a hundred times per day, it might only last three months.

For electronic switches like reed relays or optical switches that might be actuated by control circuits, lifetimes can be millions or even billions of cycles. These switches need higher reliability because they might operate many times per second in some applications.

The cycle life depends heavily on the voltage and current being switched. Switching low-voltage, low-current signals causes minimal wear and achieves the maximum rated life. Switching high voltages or high currents, especially inductive loads, causes more wear and reduces life. Manufacturers often provide graphs showing how cycle life varies with switched power.

Contact Bounce: A Hidden Challenge

One of the less obvious but important characteristics of mechanical switches is contact bounce, a phenomenon that creates unexpected behavior in digital circuits if not properly addressed.

What Is Contact Bounce

When you close a switch, you might expect the contacts to touch once and stay touching. In reality, the mechanical impact of the contacts coming together causes them to bounce apart slightly, multiple times, before finally settling into stable contact. This happens very quickly, typically over a few milliseconds, but it’s fast enough to cause problems in electronic circuits.

Imagine dropping a tennis ball on the ground. It doesn’t just stick to the ground; it bounces several times with decreasing amplitude before finally coming to rest. Switch contacts behave similarly. They make contact, bounce apart, make contact again, bounce apart again, and so on, perhaps five or ten times, before settling into solid contact.

From an electrical perspective, this means that when you close a switch once, the circuit actually closes and opens multiple times in rapid succession before staying closed. Each bounce creates a brief pulse as the circuit completes and then breaks. For a light bulb circuit, this doesn’t matter; the filament doesn’t respond fast enough to notice. But for a digital circuit processing signals at microsecond speeds, these bounces look like multiple separate switch presses.

The same thing happens when you open a switch, though it’s often less pronounced. The contacts separate, might briefly touch again as they vibrate, separate again, and finally stay separated. Again, this creates multiple pulses instead of one clean transition.

Why Contact Bounce Matters

Contact bounce is invisible and inconsequential in many applications. If you’re using a switch to turn on a motor or a light, the mechanical inertia or thermal mass of the load means it doesn’t respond to millisecond-scale pulses. The bouncing is completely filtered out by the load’s physical characteristics.

But in digital circuits, contact bounce creates serious problems. Imagine you want to use a pushbutton to increment a counter displayed on a screen. You press the button once, expecting the counter to increase by one. But because of contact bounce, the digital circuit sees five or ten switch closures in rapid succession. The counter jumps by five or ten instead of one. This is clearly unacceptable behavior.

Similarly, in applications where you’re using a switch to trigger a precise timing sequence or to latch a state change, contact bounce can cause false triggers, multiple triggers, or timing errors. Any application where the exact number of switch actuations matters is vulnerable to bounce-related problems.

The problem is particularly acute in microcontroller applications. A microcontroller might read a switch input thousands of times per second. If it reads the switch during the bounce period, it sees the multiple closures as separate events and responds to each one. This makes it impossible to detect single button presses reliably without additional measures.

Debouncing Solutions

Fortunately, contact bounce can be eliminated or mitigated through various techniques collectively called debouncing. These techniques ensure that the circuit responds to only one switch actuation even though multiple electrical pulses occur.

The simplest debouncing approach is a hardware RC filter. By placing a resistor and capacitor across the switch, you create a time constant that smooths out the rapid bounces. The capacitor charges slowly through the resistor, and the circuit only responds when the voltage crosses a threshold. The multiple bounces occur faster than the RC time constant can respond, so they’re filtered out. This is simple and effective for many applications, requiring only two extra components.

Another hardware approach uses a Schmitt trigger, a special type of circuit that has hysteresis in its switching threshold. Once the input crosses the upper threshold, the output switches and stays switched until the input crosses a lower threshold. This creates immunity to the small voltage variations caused by contact bounce. Schmitt trigger integrated circuits are widely available and provide clean debouncing with minimal components.

For microcontroller applications, software debouncing is common. The microcontroller reads the switch state, then waits for a period longer than the expected bounce time, typically 10 to 50 milliseconds. It then reads the switch again. Only if both readings agree does it consider the switch to have actually changed state. This elegant solution requires no additional hardware, just a few lines of code.

More sophisticated software debouncing algorithms use state machines that require the switch to remain stable for a certain period before registering a change. These provide even better immunity to electrical noise while reliably detecting legitimate switch actuations.

The key point is that contact bounce is a real phenomenon that must be addressed in digital circuits. Ignoring it leads to unreliable operation and frustrating bugs that can be hard to diagnose if you don’t know to look for bounce.

Switch Symbols and Reading Schematics

To use switches effectively in circuits, you need to be able to read schematic symbols that represent different switch types. These symbols convey both the electrical configuration and the mechanical operation of the switch.

Basic SPST Switch Symbol

The simplest switch symbol represents a single-pole, single-throw switch. It shows two terminals with a line between them that can make or break the connection. The line is drawn at an angle, representing the mechanical action of the switch. This symbol appears with variations to indicate whether the switch is normally open or normally closed in its default state.

A normally open switch is drawn with the connecting line not touching the opposite terminal. This indicates that in its resting state, the switch is open and no current flows. This is the most common configuration for manual switches like pushbuttons and toggle switches.

A normally closed switch shows the connecting line touching the terminal, indicating that current flows in the resting state. These are less common but used in safety applications where you want the circuit to be closed by default and require active effort to open it.

Multi-Pole and Multi-Throw Symbols

For switches with multiple poles, the schematic shows multiple independent switch elements mechanically linked. A dotted line often connects the switch symbols to indicate they operate together from one mechanical action. This clearly shows that while the circuits are electrically separate, they switch simultaneously.

Double-throw switches show one common terminal that can connect to either of two other terminals. The symbol looks like a pointer that can swing between two positions. This clearly indicates the selecting or routing function of the switch.

For DPDT switches, you’ll see two switch elements each with the common-to-two-positions configuration, linked together. This symbol immediately tells you that one mechanical action is simultaneously routing two independent circuits to one of two states each.

Understanding Switch State Notation

Switch positions are often labeled with notation that describes the contact state. The notation NO stands for normally open, meaning the contacts are open in the un-actuated state. NC stands for normally closed, meaning the contacts are closed in the un-actuated state. COM stands for common, the terminal that connects to either the NO or NC terminal depending on switch position.

This notation is particularly important for SPDT switches where you have three terminals. The COM terminal is your input or source. The NO terminal is where COM connects when the switch is actuated. The NC terminal is where COM connects when the switch is not actuated. Understanding this labeling allows you to wire switches correctly for your intended function.

Momentary Switch Indicators

Schematic symbols sometimes include annotations to indicate whether a switch is momentary or latching. Momentary switches might have a spring symbol drawn near them, or text indicating “momentary” or “push-to-close.” Without such annotation, the default assumption is typically that the switch is latching unless context suggests otherwise.

In industrial schematics, complex notation systems describe exact switch behavior including the number of positions, whether actuation is maintained or momentary, whether there are intermediate positions, and more. While these detailed notations are beyond typical hobbyist use, understanding the basic principles allows you to interpret more complex switch symbols when you encounter them.

Practical Applications and Design Considerations

Understanding switch theory is valuable, but practical application requires considering how switches integrate into real circuits and systems. Let’s explore several common applications and the design considerations they involve.

Power Switching

The most basic use of switches is controlling power to a circuit or device. When designing power switching, your primary concerns are ensuring the switch can handle the voltage and current, that it fails safe if possible, and that users can clearly see the switch state.

For low-voltage DC circuits like battery-powered projects, almost any switch of appropriate size works fine. The voltages are low enough that arcing isn’t a concern, and the currents are typically modest. The main consideration is convenience and user interface. You might choose a slide switch for a compact device, a toggle switch for a panel-mounted application, or a pushbutton if you want momentary operation.

For AC mains power switching, safety is paramount. The switches must be rated for at least 125 volts AC and preferably 250 volts AC for safety margin. They should have appropriate certifications for the region where you’ll use them. The contacts must be properly isolated to prevent shock hazards. And you should include proper fusing or circuit breaker protection.

For high-current switching, you might use a relay controlled by a low-current switch rather than switching the high current directly. This allows you to use a small, inexpensive pushbutton to control circuits carrying tens or hundreds of amps, with the relay handling the actual current switching.

Mode Selection and Input Switching

Switches are commonly used to select between different operating modes or to route signals between different paths. A multi-position rotary switch might select between different input sources to an amplifier. A DIP switch might configure operating parameters on a circuit board. A slide switch might select between different sensitivity ranges on a sensor.

For these applications, the electrical ratings are usually modest since you’re switching signal levels rather than power. The primary considerations are having enough positions for all your options, clear labeling so users know what each position does, and reliable detents that hold each position securely.

SPDT and DPDT switches are particularly useful for routing applications. An SPDT switch can route one signal to either of two destinations or select between two signal sources. A DPDT switch can perform stereo signal routing, switch polarity, or reverse motor direction.

Limit and Safety Applications

Limit switches provide automated control based on mechanical position. In these applications, reliability is crucial because the switch might be protecting equipment from damage or ensuring safe operation.

Good limit switch design includes proper mounting so the switch actuates at exactly the right position, mechanical robustness to handle repeated impacts from the moving part that triggers it, and failsafe behavior so that if the switch fails, the system shuts down safely rather than continuing operation in a dangerous state.

Many safety systems use normally closed switches in series, so that any switch failure breaks the circuit and stops operation. This ensures that failures are detected rather than allowing unsafe operation to continue.

Debouncing in Practice

For any application where you’re reading switch inputs with digital circuitry, you must implement debouncing. The specific technique depends on your requirements and constraints.

For simple applications, an RC debounce circuit is often adequate. Choose your RC time constant to be longer than the typical bounce period, around 10 to 20 milliseconds. This filters out the bounces but responds quickly enough that users don’t notice delay.

For microcontroller applications, software debouncing is typically preferred because it requires no additional components and can be tuned easily. A simple approach is to wait 20 milliseconds after detecting any switch change, then read the switch again to confirm the state. This eliminates virtually all bounce-related false triggers.

For critical applications, use both hardware and software debouncing for redundancy. The hardware provides fast filtering of the physical bounces, and the software provides additional confirmation that the switch state has actually changed.

The Evolution to Electronic Switches

While mechanical switches remain essential, modern electronics increasingly uses electronic switching where transistors or other semiconductor devices perform the switching function. Understanding how mechanical switches evolved into electronic switches provides valuable perspective on modern circuit design.

Relays as Electrically Controlled Switches

Relays bridge the gap between mechanical and electronic switches. A relay is essentially a switch controlled by an electromagnet. When you energize the electromagnet with a small current, it creates a magnetic field that pulls a mechanical armature, which closes switch contacts. Remove the current, and a spring returns the armature to its original position, opening the contacts.

Relays allow you to use low-voltage, low-current control circuits to switch high-voltage, high-current loads. They provide electrical isolation between the control circuit and the switched circuit, which is valuable for safety and noise immunity. And they can switch AC or DC loads with equal facility.

The relay is still a mechanical switch, but one that’s electrically controlled. This makes it ideal for automated control systems where switches need to be actuated by electronic signals rather than human operators.

Transistors as Solid-State Switches

Transistors can function as electrically controlled switches with no moving parts. A small current or voltage at the transistor’s base or gate terminal controls whether a much larger current can flow between the collector and emitter or between the drain and source. This is solid-state switching, using semiconductor physics instead of mechanical contacts.

Transistor switches have enormous advantages over mechanical switches. They can switch millions or billions of times per second, far faster than any mechanical system. They don’t wear out from repeated operation. They can be made incredibly small, with billions of transistors fitting on a single chip. And they consume very little power in the switching operation itself.

The entire digital revolution is built on transistor switches. Every bit stored in computer memory is held by transistor switches. Every logic gate in a processor uses transistor switches. The billions of operations per second that your computer performs are all accomplished through coordinated switching of millions of transistors.

Hybrid Approaches

Modern circuit design often combines mechanical and electronic switching. A mechanical switch provides the user interface, offering the tactile feedback and clear state indication that humans appreciate. This mechanical input is debounced and processed by electronic circuits, which then control solid-state switches that handle the actual power or signal switching.

This hybrid approach captures the best of both worlds: intuitive human interface from mechanical switches, and performance, reliability, and control capability from electronic switches.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of the Simple Switch

The switch, in its elegant simplicity, is one of the most fundamental components in all of electronics. From the earliest electrical systems to the most advanced modern computers, the concept of controllable connection and disconnection has been absolutely essential. Understanding switches thoroughly provides insights that extend far beyond the component itself.

When you flip a light switch, you’re exercising control over electricity in its most basic form. You’re making or breaking a connection, allowing or preventing current flow. This binary control, this on-or-off nature, is the foundation not just of electrical control but of digital information itself. Every bit in a computer is ultimately stored and processed by switches, whether mechanical relays in the earliest computers or nanometer-scale transistors in modern processors.

The diversity of switch types reflects the diversity of applications where control is needed. From simple SPST toggle switches to complex multi-pole rotary selectors, from momentary pushbuttons to latching power switches, each type is optimized for specific use cases. Understanding poles and throws, voltage and current ratings, momentary versus latching operation, and contact bounce allows you to select exactly the right switch for any application.

The evolution from mechanical to electronic switching demonstrates how fundamental principles persist even as implementation technology advances. A transistor performing switching functions in nanoseconds and a toggle switch flipping in milliseconds both accomplish the same basic task: controlling electrical connection. The speed and scale differ by many orders of magnitude, but the principle remains constant.

For anyone learning electronics, thoroughly understanding switches is essential. They appear in virtually every circuit, from the simplest LED project to the most complex industrial control system. Being able to read switch symbols in schematics, understand switch specifications, account for phenomena like contact bounce, and select appropriate switches for various applications is foundational knowledge that you’ll use throughout your electronics journey.

The simple act of making and breaking an electrical connection, accomplished by the humble switch, represents one of the most powerful tools humans have for controlling the flow of energy and information. From the first electrical telegraph switches that transmitted messages across continents to the billions of transistor switches inside the device you’re reading this on, switches have been enabling the electrical and digital ages. Understanding them thoroughly connects you to the fundamental principles underlying all of electrical engineering and computer science.

So the next time you flip a light switch, appreciate the elegance of what’s happening. You’re controlling the flow of electricity with a simple mechanical action. You’re exercising the same principle of switching that powers everything from your refrigerator to the supercomputers simulating the universe. That switch in your hand is a window into the fundamental nature of electrical control, and understanding it deeply is your gateway to understanding all of electronics.