Introduction: The Light Revolution in Your Hand

Hold up your smartphone in a dark room and notice how the screen illuminates your face. Look at the tiny notification light blinking in the corner. Glance at the flashlight function that can light up an entire room. All of these are powered by LEDs, Light Emitting Diodes, devices that have fundamentally transformed how we create light.

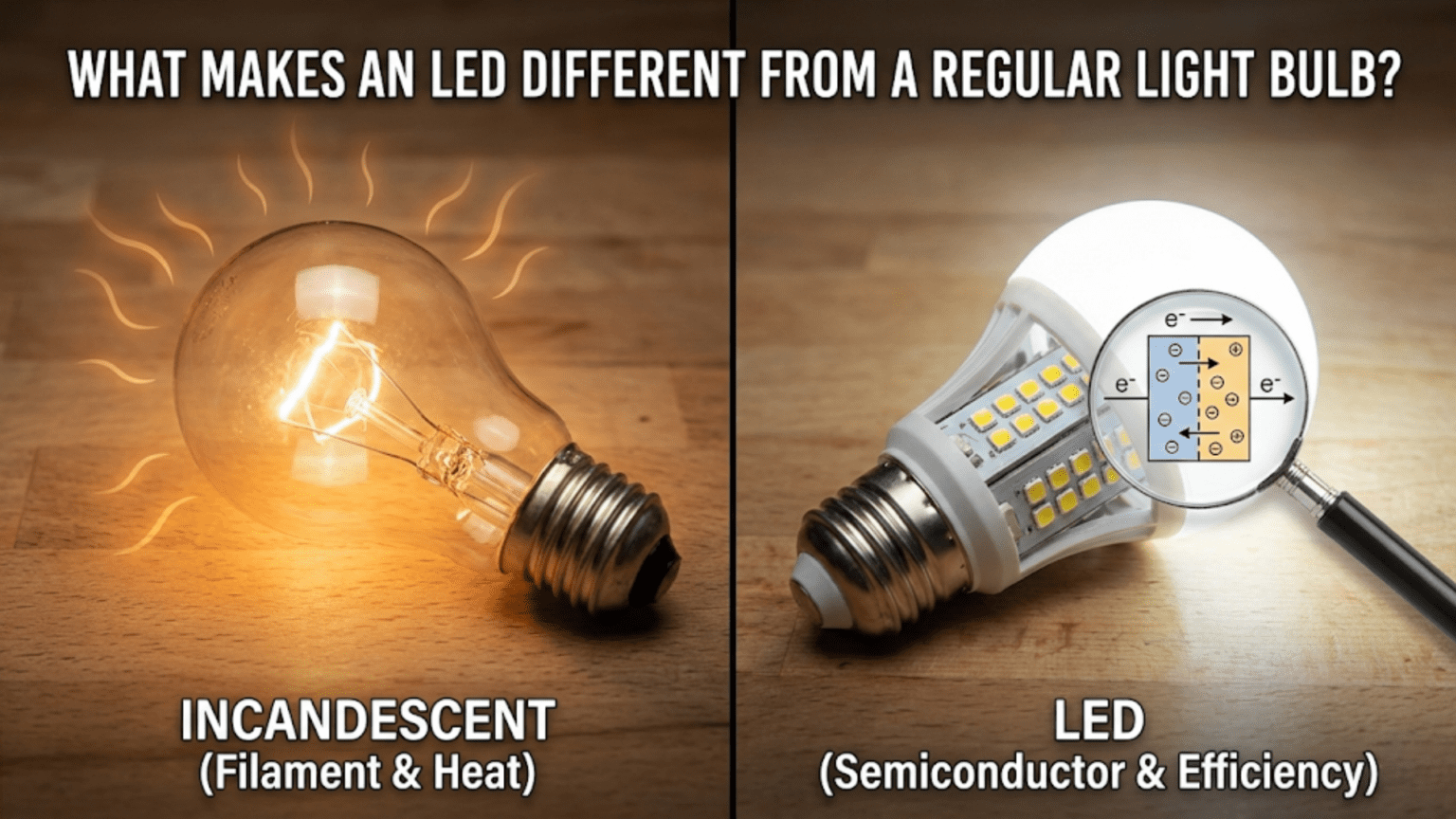

For over a century, when humans needed light, we relied on the incandescent light bulb, a technology that Thomas Edison commercialized in 1879. The basic principle was remarkably simple and remarkably inefficient: pass electricity through a thin wire until it gets so hot that it glows. It worked, but it wasted enormous amounts of energy, generated excessive heat, and the bulbs burned out regularly.

Then came LEDs. These solid-state devices create light through a completely different mechanism, one that’s far more efficient, generates much less heat, lasts dramatically longer, and offers capabilities that incandescent bulbs never could. LEDs have become so superior and so affordable that they’re rapidly making the century-old incandescent bulb obsolete. The transformation has been so complete that many countries have banned or are phasing out incandescent bulbs entirely.

But what exactly makes an LED different? How can a semiconductor, a piece of silicon or similar material, emit light? Why are LEDs so much more efficient than heating a wire until it glows? And why did it take until the 21st century for LED lighting to become widespread when the basic LED technology was invented in the 1960s?

In this comprehensive guide, we’re going to explore LEDs from the ground up. We’ll start by understanding how traditional light bulbs work to establish a baseline, then dive into the fascinating physics that allows semiconductors to emit light. We’ll examine why LEDs have such remarkable characteristics, explore the different types of LEDs and their applications, and understand both the advantages and limitations of LED technology. By the end, you’ll have a complete picture of why these little semiconductor devices have revolutionized lighting and electronics.

How Incandescent Bulbs Work: Heat Until It Glows

To appreciate what makes LEDs special, we first need to understand what they replaced. The incandescent light bulb represents one of the simplest electrical devices imaginable, yet its very simplicity reveals its fundamental inefficiency.

The Principle of Incandescence

Incandescence is the emission of light from a hot object. Heat any material to a high enough temperature, and it will glow. This is why a blacksmith’s iron glows red when heated, why lava glows orange, and why the sun shines brilliantly white-hot.

An incandescent light bulb takes advantage of this fundamental property of matter. Inside the glass bulb is a thin tungsten filament, typically coiled into a tight spiral to concentrate the heat. When you flip the switch, electricity flows through this filament. Because the filament is very thin and tungsten has resistance to electrical current, the filament heats up dramatically. The electrical energy is converted to heat through resistive heating, the same principle that makes electric stoves and space heaters work.

As the tungsten filament reaches temperatures around 2,500 to 3,000 degrees Celsius (4,500 to 5,400 degrees Fahrenheit), it begins to glow, emitting visible light. The higher the temperature, the brighter and whiter the light. Edison and other early inventors chose tungsten because it has the highest melting point of any pure metal (3,422°C), allowing it to reach the high temperatures needed for bright white light without melting.

The glass bulb is filled with an inert gas like argon or nitrogen, or evacuated to create a vacuum. This prevents the hot tungsten from reacting with oxygen, which would cause it to burn up instantly. Even with this protection, tungsten atoms slowly evaporate from the filament over time, making it thinner and more fragile until it eventually breaks, causing the bulb to “burn out.”

The Efficiency Problem

Here’s the fundamental problem with incandescent bulbs: they’re terribly inefficient at producing light. When you heat something to make it glow, most of the energy goes into infrared radiation (heat) rather than visible light. A typical incandescent bulb converts only about 5% of the electrical energy into visible light. The other 95% becomes heat.

Think about that for a moment. If you’re using a 100-watt incandescent bulb, only about 5 watts worth of the electricity is actually producing the light you want. The other 95 watts is heating your room. In the summer, this waste heat then forces your air conditioning to work harder to remove it, wasting even more energy.

This inefficiency isn’t a design flaw that could be fixed. It’s a fundamental limitation of the physics of incandescence. The spectrum of light emitted by a hot object depends on its temperature, described by Planck’s law of black body radiation. At the temperatures tungsten can withstand without melting, the majority of the radiation is inherently in the infrared range. You can’t make an incandescent bulb dramatically more efficient without changing the fundamental principle of operation.

Other Limitations

Beyond inefficiency, incandescent bulbs have other significant limitations. Their lifetime is typically only 1,000 to 2,000 hours because the tungsten filament gradually evaporates and weakens. They’re fragile because the thin hot filament breaks easily when subjected to vibration or shock. They don’t work well in cold environments because the filament needs to reach high temperature to produce light. And they can’t be dimmed to very low levels without the color temperature shifting significantly toward red.

The incandescent bulb served humanity well for over a century, but it was always a compromise solution, waiting for something better to come along. That something better turned out to be the LED.

How LEDs Work: Light from Electron Energy

LEDs create light through an entirely different mechanism called electroluminescence. Instead of heating something until it glows, LEDs convert electrical energy directly into light through quantum mechanical processes happening at the atomic level. To understand how this works, we need to explore some fundamental physics.

Energy Levels in Atoms and Semiconductors

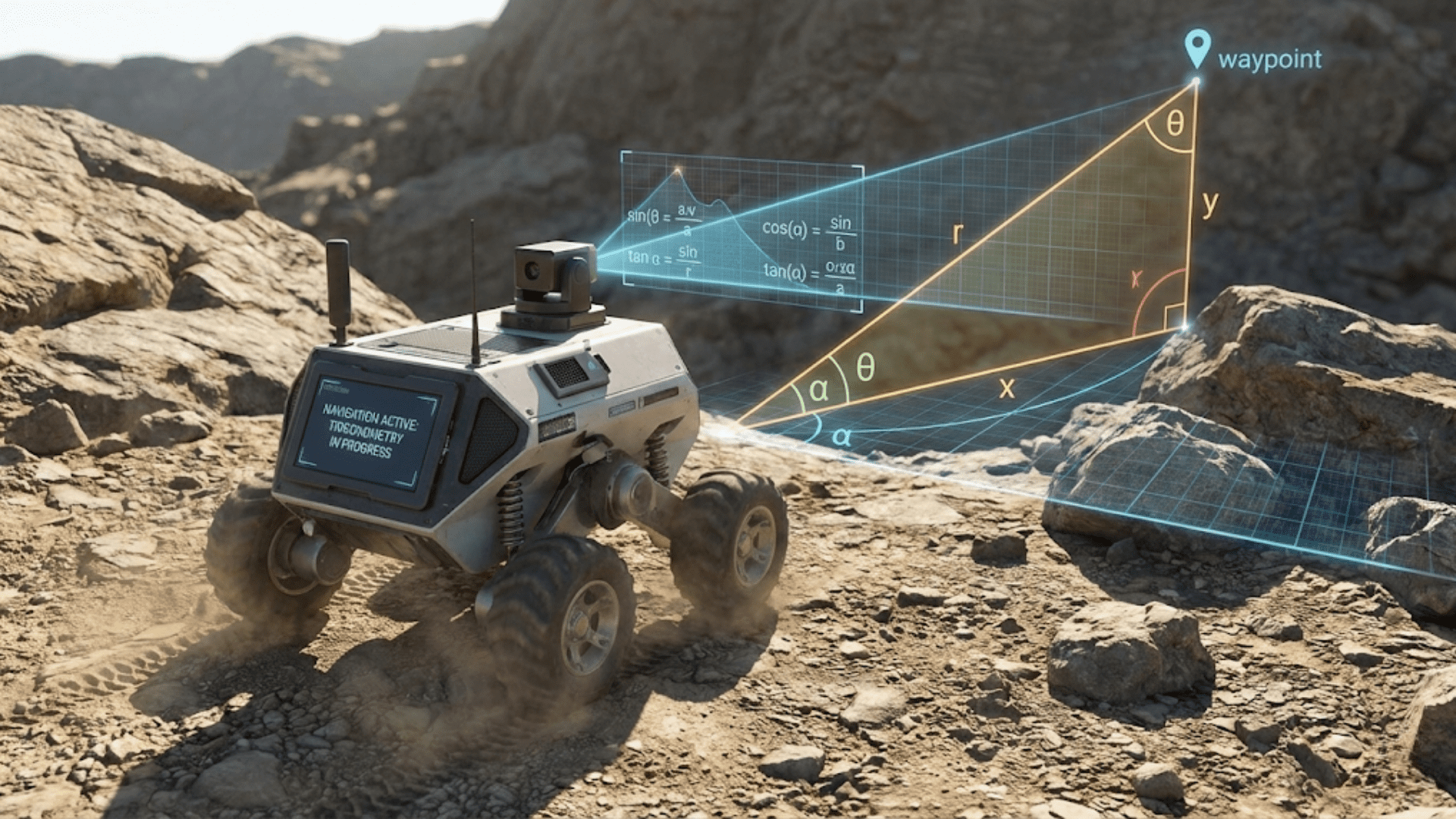

Every electron in an atom exists at a specific energy level. Think of these energy levels as steps on a ladder. An electron can be on the first step, second step, third step, and so on, but it can’t exist between steps. This quantization of energy is a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics.

When an electron moves from a higher energy level to a lower one, it must release the exact amount of energy corresponding to the difference between those levels. This energy is released as a photon, a particle of light. The energy of the photon determines its color; high energy photons appear as blue or violet light, medium energy photons as green or yellow, and lower energy photons as red or infrared.

In isolated atoms, these energy levels are discrete and well-separated. But in a solid material, particularly a semiconductor, atoms are packed closely together in a crystal structure. The energy levels of neighboring atoms interact and overlap, forming continuous bands of allowed energies. In a semiconductor, there’s a valence band where electrons normally reside when they’re bound to atoms, and a conduction band where electrons can move freely through the crystal. Between these bands is a gap, called the band gap, where no electron can exist.

The band gap is crucial for understanding LEDs. When an electron in the conduction band falls down into the valence band, it must release energy equal to the band gap. In certain semiconductor materials, this energy is released as a photon of light. The color of that light depends on the size of the band gap: larger band gaps produce higher energy photons (bluer light), while smaller band gaps produce lower energy photons (redder light).

The PN Junction Revisited

An LED is fundamentally a diode, with a PN junction between P-type and N-type semiconductor material. When you forward bias an LED by applying a positive voltage to the P-type side (anode) and negative voltage to the N-type side (cathode), electrons are injected from the N-type material into the P-type material, and holes are injected in the opposite direction.

When these electrons and holes meet in the junction region, they recombine. An electron falls from the conduction band into a hole in the valence band, dropping down the energy ladder by an amount equal to the band gap. In ordinary silicon diodes, this energy is released primarily as heat, through vibrations in the crystal lattice (phonons). But in certain semiconductor materials with what’s called a direct band gap, the energy is released efficiently as photons.

This is the magic of the LED: the controlled recombination of electrons and holes at a PN junction, with the energy released as visible light instead of just heat. It’s a fundamentally more efficient process than heating a wire, because we’re directly converting electrical energy into light energy without the intermediate step of creating heat.

Why Material Matters: Direct vs Indirect Band Gaps

Not all semiconductor materials make good LEDs. Silicon, the workhorse of the electronics industry, makes terrible LEDs even though it’s a semiconductor with a band gap. The problem is that silicon has an indirect band gap.

In materials with a direct band gap, when an electron drops from the conduction band to the valence band, it can release a photon directly. The transition is efficient, and most of the energy becomes light. Materials like gallium arsenide (GaAs), gallium nitride (GaN), and gallium phosphide (GaP) have direct band gaps and make excellent LEDs.

In materials with an indirect band gap like silicon or germanium, the electron transition requires not just the emission of a photon but also interaction with the crystal lattice. This makes photon emission much less probable; most of the energy is released as vibrations (heat) instead. This is why silicon diodes don’t glow when you run current through them, even though electrons and holes are recombining at the junction.

The discovery and development of direct band gap semiconductor materials specifically for LEDs was a major breakthrough that took decades of materials science research. Early LEDs in the 1960s were very dim and only available in red. It wasn’t until the 1990s that bright blue LEDs were developed, which then enabled white LEDs and the lighting revolution we’re experiencing today.

Creating Different Colors

The color of light from an LED is determined by the band gap energy of the semiconductor material. By carefully choosing materials and their compositions, LED manufacturers can create devices that emit specific colors.

Red LEDs, the first commercially available, typically use gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) or aluminum gallium arsenide (AlGaAs). These materials have relatively small band gaps, corresponding to photon energies in the red portion of the spectrum. The forward voltage of red LEDs is typically around 1.8 to 2.2 volts, reflecting this lower photon energy.

Green LEDs often use gallium phosphide (GaP) or aluminum gallium phosphide (AlGaP). Yellow LEDs use similar materials with slightly different compositions. These have larger band gaps than red LEDs, so they require higher forward voltages, typically 2.0 to 2.5 volts.

Blue LEDs were the great challenge of LED development. They require even larger band gaps, corresponding to higher photon energies. The breakthrough came in the 1990s with the development of gallium nitride (GaN) and indium gallium nitride (InGaN) LEDs. Blue LEDs typically have forward voltages of 3.0 to 3.6 volts, reflecting their higher photon energy.

The development of efficient blue LEDs was so important that the inventors were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2014. Why was blue so important? Because once you have blue LEDs, you can create white light, which opened up the possibility of using LEDs for general illumination, not just indicator lights and displays.

Making White Light

White light is actually a mixture of different colors across the visible spectrum. There are two main ways to create white light from LEDs.

The first method uses a blue LED combined with a phosphor coating. The blue LED emits blue light, but some of this light hits a yellow phosphor material that absorbs the blue photons and re-emits them as a broad spectrum of yellow light. The combination of the remaining blue light and the yellow phosphor emission appears white to our eyes. This is the most common method for white LEDs and is used in most LED light bulbs.

The second method combines red, green, and blue LEDs in a single package. By adjusting the relative intensities of the three colors, you can create white light. This RGB (red-green-blue) approach allows for adjustable color temperature and even color-changing effects, which is why it’s used in applications like stage lighting, smart bulbs, and display backlights. However, it’s more complex and expensive than the phosphor method.

The color quality of white LEDs is measured by the Color Rendering Index (CRI) and color temperature. CRI indicates how accurately the LED light renders colors compared to natural sunlight; higher CRI values (80-100) give more natural color appearance. Color temperature, measured in Kelvin, describes whether the white light appears warm (yellowish, like incandescent bulbs at 2700K) or cool (bluish, like daylight at 5000-6500K).

The Efficiency Advantage: Why LEDs Win

The fundamental difference in how LEDs produce light gives them enormous advantages in energy efficiency compared to incandescent bulbs.

Direct Energy Conversion

Remember that an incandescent bulb converts electrical energy to heat, then relies on some of that heat being radiated as visible light. This two-step process is inherently inefficient because most of the thermal radiation is in the infrared range, not visible light.

An LED, by contrast, directly converts electrical energy into light through the recombination of electrons and holes. The energy of the photon emitted equals the band gap energy, which is chosen specifically to be in the visible range. There’s no heat as an intermediate step in the light generation process itself.

Now, LEDs aren’t 100% efficient. Some electrical energy is still lost as heat due to resistance in the semiconductor and electrical connections, and not every electron-hole recombination produces a photon even in direct band gap materials. But modern LEDs can convert 40% to 50% of electrical energy into visible light, compared to about 5% for incandescent bulbs. That’s an 8 to 10 times improvement in efficiency.

In practical terms, an LED bulb producing the same amount of light as a 60-watt incandescent bulb might only consume 8 to 10 watts. Over the lifetime of the bulb, this saves enormous amounts of electricity. If you leave a light on for 4 hours per day, replacing a 60W incandescent with a 9W LED saves about 75 kilowatt-hours per year, which translates to roughly $10 per year at typical electricity rates. Multiply that by every light in your home and building worldwide, and the energy savings are staggering.

Heat Management

Because LEDs are much more efficient, they generate much less waste heat for the same amount of light. This has multiple benefits beyond just energy savings.

Less heat means LEDs stay cooler during operation. While they do need some heat management in high-power applications, they never approach the hundreds or thousands of degrees that incandescent filaments reach. This makes LEDs much safer; they don’t get hot enough to cause burns or start fires if they come in contact with flammable materials.

The lower operating temperature also contributes to the long lifetime of LEDs. High heat degrades materials over time, which is part of why incandescent filaments eventually fail. LEDs operating at relatively cool temperatures experience much less thermal stress and degradation.

However, it’s important to understand that LED efficiency decreases as temperature increases. The semiconductor physics involved is temperature-dependent, and higher junction temperatures lead to lower light output and accelerated degradation. This is why high-power LED fixtures often include substantial heatsinks and sometimes even active cooling with fans. The goal isn’t just to protect the LED from damage, but to keep it cool for maximum efficiency and lifetime.

Spectrum Control

Another subtle but important efficiency advantage comes from spectrum control. An incandescent bulb emits a broad spectrum of light, much of it in infrared wavelengths that our eyes can’t see. Even the visible portion includes all colors, whether you need them or not.

LEDs emit a narrow spectrum centered on a specific color determined by their band gap. If you need red light for a traffic signal or a display, a red LED emits almost pure red light, wasting almost no energy on other colors. Even white LEDs, while having a broader spectrum, are optimized to emit primarily in the visible range with minimal infrared.

This spectrum control also means LEDs can be optimized for specific applications. Growing plants? Use LEDs with spectra tailored to the wavelengths plants use for photosynthesis. Treating seasonal affective disorder? Use LEDs with spectra that mimic natural daylight. These applications were impossible with incandescent bulbs, which produce whatever spectrum results from their temperature.

Longevity and Durability: Built to Last

Beyond efficiency, LEDs have remarkable longevity compared to incandescent bulbs, stemming from their solid-state construction and lower operating temperatures.

No Filament to Break

The fundamental weakness of incandescent bulbs is the filament. It’s a thin wire heated to extreme temperatures, subjected to thermal stress every time you turn the light on or off. Vibrations from nearby activity can cause the hot, fragile filament to break. The tungsten atoms gradually evaporate, making the filament thinner and weaker over time until it eventually fails.

An LED has no filament, no moving parts, no vacuum to lose. It’s a solid piece of semiconductor material with electrical connections. When you turn an LED on, nothing has to heat up to thousands of degrees; electrons simply start flowing through the junction and light appears almost instantly. There’s no thermal shock, no mechanical weakness, no gradual evaporation of material.

This solid-state construction makes LEDs remarkably durable. They can withstand vibration and mechanical shock that would instantly destroy an incandescent bulb. This is why LEDs have become universal in automotive applications, where vibration is constant, and in portable devices that get dropped and jostled.

Rated Lifetime Comparisons

A typical incandescent bulb is rated for about 1,000 hours of operation. Use it for 3 hours per day, and it lasts less than a year. A typical LED bulb is rated for 25,000 to 50,000 hours. At the same usage rate, that’s 23 to 45 years. Even accounting for failures and degradation, you might only need to replace an LED bulb a few times in your entire life.

This longevity has profound practical implications. For residential lighting, it means you replace bulbs far less frequently, saving time and money. For commercial and industrial applications, where labor costs for changing bulbs can exceed the bulb cost, it’s transformative. Street lights, stadium lights, and high-bay industrial lights that require boom lifts or scaffolding to access can now operate for years without maintenance.

However, it’s important to understand what “lifetime” means for LEDs. Unlike incandescent bulbs that work fine until they suddenly burn out, LEDs gradually dim over time. The rated lifetime typically refers to when the LED has degraded to 70% or 80% of its initial brightness (this is often labeled as L70 or L80). The LED will continue working beyond this point, just with reduced output.

Degradation Mechanisms

LEDs do eventually degrade, even though they don’t “burn out” in the traditional sense. The main degradation mechanisms relate to the semiconductor materials and the packaging.

High temperatures accelerate degradation of the semiconductor crystal structure, causing defects that reduce efficiency. This is why good thermal management is crucial for LED lifetime. The electrical connections can also degrade over time, especially if the LED experiences many thermal cycles.

The packaging materials can yellow or degrade when exposed to UV light and high temperatures, reducing light transmission. The phosphor in white LEDs can degrade, shifting the color temperature over time. Cheap LED products often fail prematurely due to inadequate packaging or poor thermal design rather than failure of the LED chip itself.

Quality LED products from reputable manufacturers will reliably achieve their rated lifetimes when operated within specifications. Cheaper products may fail much sooner, particularly if they’re overdriven (operated at higher than rated current) or poorly heat-managed.

Operating Characteristics: What Makes LEDs Unique

LEDs behave quite differently from incandescent bulbs in how they respond to voltage and current, and understanding these characteristics is essential for using them properly.

Current-Driven Devices

Incandescent bulbs are essentially resistors. Apply a voltage, and current flows according to Ohm’s law. The resistance increases slightly as the filament heats up, but it’s relatively stable. You can connect an incandescent bulb directly to a voltage source; the bulb’s resistance limits the current automatically.

LEDs are completely different. They’re diodes, and like all diodes, they have an exponential current-voltage relationship. Below the forward voltage threshold (typically 1.8V to 3.6V depending on color), almost no current flows. Right around the threshold, small increases in voltage cause dramatic increases in current. Above the threshold, the voltage across the LED stays relatively constant while current can increase enormously.

This means you cannot connect an LED directly to a voltage source without current limiting. If you connect a red LED (2.0V forward voltage) directly to a 5V power supply, the LED will try to draw whatever current is necessary to drop the voltage to 2V. This could be many amps, instantly destroying the LED.

LEDs are current-driven devices. To operate them properly, you need to control the current flowing through them, not the voltage across them. The brightness of an LED is approximately proportional to the current; more current means more photons emitted per second, which we perceive as brighter light.

The Necessity of Current Limiting

The most common way to limit current through an LED is with a series resistor. If you have a 5V supply and a red LED with a 2V forward drop, you need to drop the remaining 3V across a resistor. If you want 20 milliamps of current, Ohm’s law tells you that you need a 3V / 0.02A = 150 ohm resistor.

This resistor method is simple and works fine for single LEDs or small numbers of LEDs in low-power applications. However, it has a significant disadvantage: the resistor wastes power as heat. In our example, the resistor dissipates 3V × 0.02A = 0.06 watts, while the LED itself only uses 2V × 0.02A = 0.04 watts. We’re wasting 60% of the power in the resistor.

For high-power LED applications like light bulbs or street lights, wasting that much power is unacceptable. Instead, these applications use constant-current LED drivers, which are switching power supplies specifically designed to deliver a precise current regardless of voltage variations. These drivers can be over 90% efficient, wasting very little power.

Temperature Sensitivity

LED characteristics change with temperature. As an LED heats up, its forward voltage decreases slightly, which tends to increase current if the LED is connected to a voltage source. This creates a potential thermal runaway situation: more current causes more heat, which decreases forward voltage, which increases current further.

This is another reason why constant-current drive is important for LEDs. With current held constant, temperature changes don’t cause runaway conditions. However, even with constant current, LED efficiency decreases at higher temperatures, so thermal management remains important.

The color of LED emission can also shift slightly with temperature, which matters for applications requiring precise color matching. High-quality LED products compensate for these temperature effects in their drive circuitry.

Instant On/Off

One delightful characteristic of LEDs compared to incandescent bulbs is their instant response. Flip the switch on an LED, and it’s at full brightness in nanoseconds to microseconds. There’s no warm-up time, no gradual brightening as a filament heats up.

This instant response enables applications impossible with incandescent bulbs. LEDs can be switched on and off thousands of times per second without damage, enabling pulse-width modulation (PWM) dimming where brightness is controlled by rapidly switching the LED on and off too fast for the eye to perceive. The duty cycle (fraction of time the LED is on) determines the perceived brightness.

This fast switching also enables LEDs to transmit data. Visible Light Communication (VLC) systems can modulate LED intensity at megahertz rates to transmit information through light, essentially using LEDs as both illumination and wireless communication transceivers.

Dimming Behavior

Incandescent bulbs dim smoothly when you reduce voltage, though their color shifts toward red at low brightness. LEDs are trickier to dim properly.

If you try to dim an LED by reducing current, it does get dimmer, but the efficiency typically drops and the color can shift. Very low currents may cause flickering or uneven light output.

The preferred dimming method for LEDs is PWM, switching them fully on and off at high frequency. At 50% duty cycle (on half the time), the LED appears half as bright to the human eye, which can’t respond fast enough to see the individual flashes. The LED always operates at optimal current when it’s on, maintaining good efficiency and color stability.

Some LED products use analog dimming (reducing current) at very low brightness levels where PWM would be too slow and visible, then switch to PWM for normal dimming range. Designing good dimming LED drivers is actually quite sophisticated engineering.

Applications: Where LEDs Excel

The unique characteristics of LEDs have made them dominant in many applications and enabled entirely new capabilities.

Indicator Lights and Displays

LEDs first became common in the 1970s as indicator lights and seven-segment displays. Their small size, low power consumption, long life, and available colors made them perfect for these applications. Today, virtually every electronic device uses LED indicators for power, status, and alerts.

The ability to make LEDs extremely small enabled dense displays. LED displays in stadiums, billboards, and Times Square create enormous video screens from millions of individual LEDs. The brightness and weather resistance of LEDs make them far superior to any previous display technology for outdoor applications.

Television and monitor displays now use LED backlights instead of the fluorescent backlights that dominated for years. This enables thinner displays, better brightness control, and in some cases, local dimming where parts of the backlight can be turned off for deeper blacks.

General Illumination

The development of bright white LEDs in the early 2000s opened up the possibility of using LEDs for general lighting. Initially expensive and with mediocre color quality, LED bulbs have rapidly improved while costs have plummeted.

Today, LED bulbs designed to replace incandescent and fluorescent bulbs are available everywhere, cost just a few dollars, and offer massive energy savings with lifetimes of decades. The lighting industry has fundamentally transformed; major lighting manufacturers have largely abandoned incandescent and fluorescent technology.

LED lighting offers capabilities impossible with previous technologies. Color-changing bulbs with red, green, and blue LEDs can create any color on demand, controlled by smartphone apps. Tunable white bulbs can shift from warm evening light to bright daylight color. Integrated smart features can automate lighting based on schedules, occupancy, or ambient light levels.

Automotive Lighting

LEDs have revolutionized automotive lighting. Brake lights, turn signals, and running lights universally use LEDs now. Their instant response (important for brake lights, where milliseconds matter), resistance to vibration, and long lifetime make them ideal.

Headlights are increasingly LED-based as well. LED headlights can be brighter than halogen, more efficient, and last the lifetime of the vehicle. Adaptive headlights that steer the beam based on vehicle direction or dim portions to avoid blinding oncoming drivers are easier to implement with the precise control possible with LEDs.

The small size of individual LEDs also enables creative automotive design. A taillight can be made from dozens of small LEDs arranged in intricate patterns, creating distinctive styling that would be impossible with traditional bulbs.

Specialty Applications

LEDs enable many specialty applications impossible with other light sources. UV LEDs are used for sterilization, curing of adhesives and coatings, and counterfeit detection. Infrared LEDs are used in remote controls, security cameras for night vision, and optical communication systems.

Horticultural lighting uses LEDs with spectra optimized for plant growth, providing only the wavelengths plants need for photosynthesis while minimizing wasted energy on other colors. This enables efficient indoor farming and supplemental greenhouse lighting.

Medical applications use specific LED wavelengths for treatments ranging from jaundice in newborns to photodynamic therapy for certain cancers. The precise wavelength control and safety of LEDs make them valuable medical tools.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their many advantages, LEDs aren’t perfect for every application, and they present some unique challenges.

Initial Cost

While LED prices have dropped dramatically, LED products still typically cost more upfront than incandescent bulbs. A 60W-equivalent LED bulb might cost $3 to $5, while an incandescent bulb costs under $1. However, the lifetime energy savings and reduced replacement costs make LEDs far more economical over their lifetime. The payback period is typically less than a year.

For consumers focused on initial cost rather than lifetime cost, incandescent bulbs might seem more attractive. This is becoming less of a factor as LED prices continue to fall and many regions ban or heavily tax incandescent bulbs.

Heat Management in High-Power Applications

While LEDs generate much less waste heat than incandescent bulbs for the same light output, high-power LEDs still need thermal management. A 100W-equivalent LED bulb might consume 14 watts, with perhaps 6-7 watts becoming heat. That heat must be removed to keep the LED junction cool for longevity and efficiency.

LED bulbs designed to replace incandescent bulbs include heatsinks, often the aluminum body of the bulb. High-power LED fixtures like floodlights have substantial heatsinks or even active cooling. Poor thermal design is the most common cause of premature LED failure.

Blue Light Concerns

White LEDs made with blue LED plus phosphor emit significant blue light. There’s ongoing research and debate about whether blue-rich LED lighting affects sleep patterns by suppressing melatonin production, or whether high-energy blue light might affect eye health over long-term exposure.

The evidence is still developing, but many LED products now offer warm white color temperatures (2700K-3000K) with less blue content for residential use, saving cooler daylight color temperatures (5000K+) for task lighting where alertness is desired. Some products offer circadian-friendly color temperature shifting, cooler during the day and warmer in the evening.

Compatibility Issues

LED bulbs designed to replace incandescent bulbs sometimes have compatibility issues with existing infrastructure. Dimmer switches designed for incandescent loads may not work properly with LED bulbs, causing flickering or limited dimming range. LED manufacturers now make “dimmable” bulbs compatible with most dimmers, but matching specific dimmers to specific LEDs can still be trial-and-error.

Three-way bulbs, fixture mounting issues, and enclosed fixture compatibility (where heat buildup is problematic for LEDs) can present challenges. Motion sensors and timers designed for incandescent loads may not work with low-power LEDs.

Color Quality Variability

Not all white LEDs render colors equally well. Cheap LED products may have low CRI (Color Rendering Index), making colors appear washed out or inaccurate. Better products specify CRI of 80, 90, or even 95+, which gives more natural color appearance.

Color temperature can also vary between bulbs, even from the same manufacturer. If you’re replacing one bulb in a multi-bulb fixture, the new LED might not match the existing ones perfectly, creating an inconsistent appearance.

The Future of LED Technology

LED technology continues to advance rapidly, with ongoing research pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.

Micro-LEDs and Mini-LEDs

The latest frontier in display technology is micro-LEDs, where individual LEDs are just a few micrometers in size. Displays made from millions of these tiny LEDs can achieve incredible brightness, perfect blacks (by turning off individual LEDs), and no burn-in issues that plague OLED displays.

Mini-LEDs, slightly larger at hundreds of micrometers, are already appearing in high-end TVs and monitors as backlight sources, enabling fine-grained local dimming for better contrast ratios than traditional LED backlights.

Higher Efficiency

While modern LEDs are already very efficient, research continues on new materials and structures to push efficiency even higher. The theoretical maximum efficiency for white LEDs under ideal conditions exceeds 300 lumens per watt; commercial products today achieve 100-150 lumens per watt, leaving room for further improvement.

Improved phosphors for white LEDs with better color rendering and efficiency are an active area of research. New semiconductor materials and quantum dot technologies may enable even better performance.

New Applications

As LED costs continue to fall and capabilities improve, new applications emerge. Li-Fi (Light Fidelity) using modulated LEDs for wireless communication could provide alternatives to Wi-Fi in certain environments. Quantum dots combined with LEDs might enable displays with color gamuts exceeding anything previously possible.

Agricultural applications continue to expand as research identifies optimal spectral recipes for different plants and growth stages. Medical applications leveraging specific wavelengths for diagnosis and treatment continue to develop.

Conclusion: A Light Revolution Complete

The LED represents one of the most successful technology transitions in history. In just a few decades, LEDs have gone from expensive, dim indicators available only in red to the dominant lighting technology, replacing century-old incandescent technology and fluorescent technology developed in the 1930s.

What makes LEDs different from regular light bulbs? Fundamentally, it’s the mechanism of light generation. Instead of heating a wire until it glows, wasting 95% of the energy as unwanted heat, LEDs convert electrical energy directly into light through quantum mechanical processes in semiconductors. This enables efficiency improvements of 8 to 10 times, lifetimes 25 to 50 times longer, instant response, precise color control, and capabilities impossible with thermal light sources.

The physics underlying LEDs, the quantum mechanics of semiconductors and band gaps, represents some of the most profound scientific understanding of the 20th century. Turning that understanding into practical, affordable products required decades of materials science research and manufacturing development. The Nobel Prize awarded to the inventors of blue LEDs recognized how important this technology is to humanity.

For anyone learning electronics, understanding LEDs is essential not just for practical circuit design, but for appreciating how quantum physics translates into everyday technology. LEDs demonstrate how semiconductor physics enables capabilities far beyond what classical physics could provide. They’re a tangible example of how deep scientific understanding creates practical value.

The transition to LED lighting is largely complete in developed countries and accelerating worldwide. The energy savings are enormous; the International Energy Agency estimates that LED adoption will save over 1,400 terawatt-hours annually by 2030, equivalent to the electricity consumption of all of Africa. The reduction in power plant requirements and greenhouse gas emissions represents a significant contribution to addressing climate change.

Beyond lighting, LEDs enable the displays in our devices, the communications infrastructure of fiber optics, new medical treatments, and countless other applications. They demonstrate how a simple PN junction, the same basic structure used in the first transistors and diodes, can be optimized for an entirely different purpose, creating value across civilization.

The humble LED, blinking on your microwave or illuminating the room you’re sitting in, represents a complete revolution in how humanity creates light. From Edison’s heated tungsten wire to semiconductors emitting photons through electron-hole recombination, the journey reflects both tremendous scientific progress and the practical impact that electronics has on daily life. Every time you flip a switch and an LED lights up instantly, cool to the touch and sipping minimal power, you’re experiencing the difference that understanding and applying quantum mechanics makes in the real world.