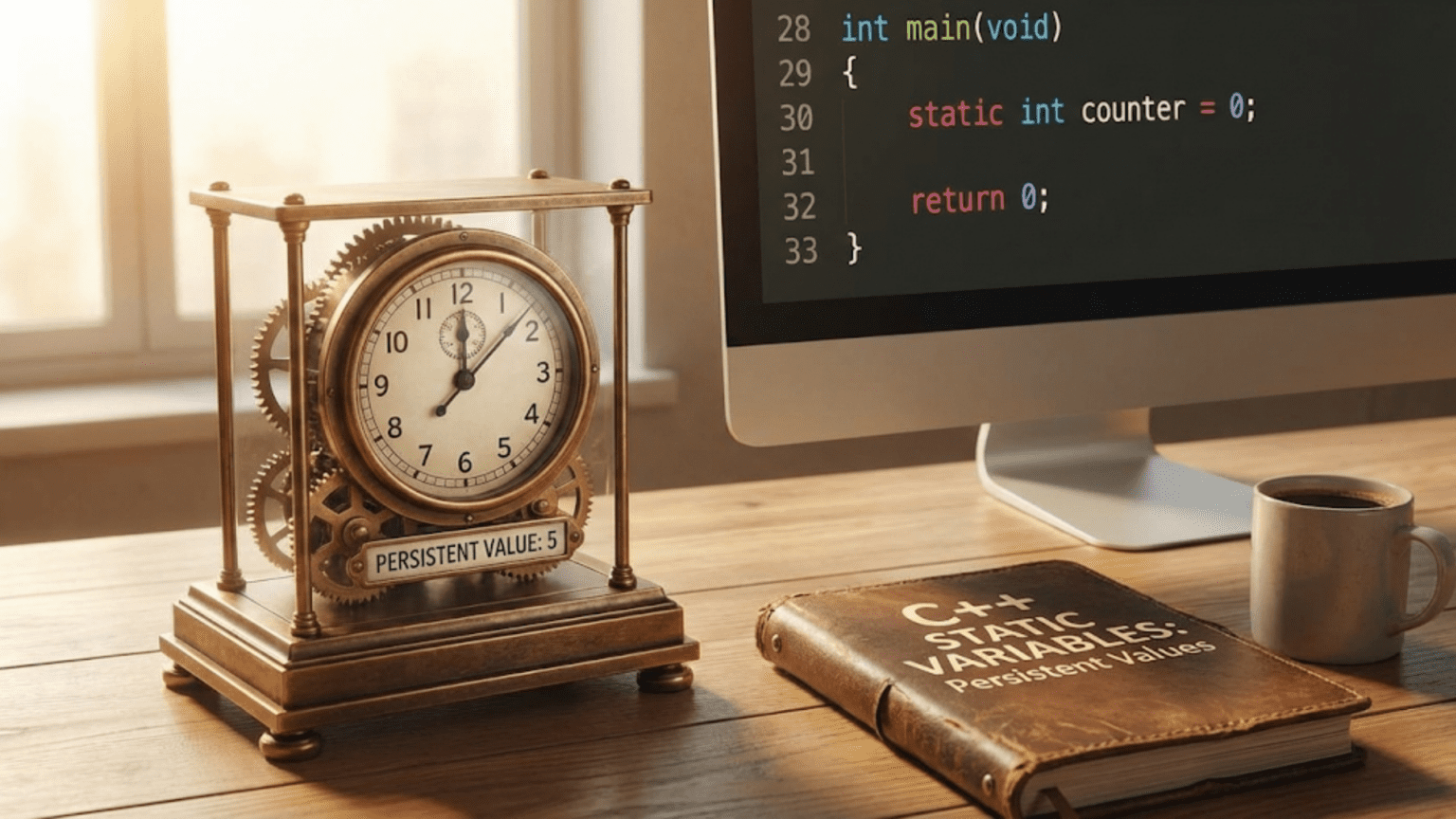

When you declare a regular local variable inside a function, it comes into existence when the function is called and disappears when the function returns, losing its value completely. If you call the function again, you get a brand new variable starting from its initial value with no memory of previous calls. But what if you need a variable that persists between function calls, maintaining its value across multiple invocations? Or what if you want a variable that belongs to a class itself rather than to individual objects of that class? The static keyword solves both these problems by fundamentally changing how variables behave, giving them lifetime that extends beyond normal scope rules while controlling their visibility and initialization in precise ways.

Think of static variables like a notebook that stays in a desk drawer between meetings. When you attend a meeting in a conference room, you might bring a notepad, jot down notes during the meeting, then throw the notepad away when you leave. That’s like a regular local variable—created for each meeting, discarded afterwards. But if you keep a dedicated notebook in the desk drawer that stays there permanently, you can refer back to notes from previous meetings and add new notes each time. That notebook persists between meetings while remaining associated with that specific room. Static variables work similarly—they persist between function calls while remaining associated with their scope, maintaining state across multiple executions.

The power of static variables comes from enabling several important patterns that would otherwise require awkward workarounds. You can count how many times a function has been called without using global variables. You can share data among all instances of a class without making it global. You can ensure expensive initialization happens only once rather than repeatedly. You can create singleton patterns where only one instance of something should exist. Understanding static variables transforms how you manage state in programs, enabling cleaner designs where data persists exactly as long as needed while remaining properly encapsulated within appropriate scopes.

Let me start by showing you static local variables—variables declared inside functions that maintain their values between calls:

#include <iostream>

void countCalls() {

static int callCounter = 0; // Initialized only once, persists between calls

callCounter++;

std::cout << "This function has been called " << callCounter << " times" << std::endl;

}

void demonstratePersistence() {

static int value = 10; // Initialized first time function is called

std::cout << "Value at start: " << value << std::endl;

value += 5;

std::cout << "Value at end: " << value << std::endl;

}

int generateUniqueID() {

static int nextID = 1000; // Starts at 1000, increments each call

return nextID++;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Counting Function Calls ===" << std::endl;

countCalls();

countCalls();

countCalls();

std::cout << "\n=== Demonstrating Persistence ===" << std::endl;

demonstratePersistence(); // value goes from 10 to 15

demonstratePersistence(); // value goes from 15 to 20

demonstratePersistence(); // value goes from 20 to 25

std::cout << "\n=== Generating Unique IDs ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID 1: " << generateUniqueID() << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID 2: " << generateUniqueID() << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID 3: " << generateUniqueID() << std::endl;

return 0;

}The static keyword changes the storage duration of local variables from automatic to static, meaning they’re created once when the program starts (or more precisely, when execution first reaches their declaration) and persist until the program ends. The initialization happens only once—when execution first reaches the static variable declaration. On subsequent function calls, the initialization is skipped and the variable retains whatever value it had from the previous call. This creates persistent state within the function’s scope, enabling patterns like counters, caches, and unique ID generators without resorting to global variables.

Static member variables belong to the class itself rather than to individual objects, making them shared among all instances of the class:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class BankAccount {

private:

std::string accountNumber;

double balance;

// Static member variable - shared by all BankAccount instances

static int totalAccounts;

static double totalDeposits;

public:

BankAccount(const std::string& accNum, double initialBalance)

: accountNumber(accNum), balance(initialBalance) {

totalAccounts++; // Each new account increments the shared counter

std::cout << "Account " << accountNumber << " created. Total accounts: "

<< totalAccounts << std::endl;

}

~BankAccount() {

totalAccounts--; // Account destroyed, decrement counter

}

void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount;

totalDeposits += amount; // Update shared total

std::cout << "Deposited $" << amount << " to " << accountNumber << std::endl;

}

}

// Static member function - can only access static members

static int getTotalAccounts() {

return totalAccounts;

}

static double getTotalDeposits() {

return totalDeposits;

}

void displayBalance() const {

std::cout << "Account " << accountNumber << ": $" << balance << std::endl;

}

};

// Static member variables must be defined outside the class

int BankAccount::totalAccounts = 0;

double BankAccount::totalDeposits = 0.0;

int main() {

std::cout << "Initial total accounts: " << BankAccount::getTotalAccounts() << std::endl;

BankAccount acc1("ACC001", 1000);

BankAccount acc2("ACC002", 500);

std::cout << "\nTotal accounts now: " << BankAccount::getTotalAccounts() << std::endl;

acc1.deposit(200);

acc2.deposit(300);

acc1.deposit(150);

std::cout << "\nTotal deposits across all accounts: $"

<< BankAccount::getTotalDeposits() << std::endl;

{

BankAccount acc3("ACC003", 750);

std::cout << "Total accounts with acc3: " << BankAccount::getTotalAccounts() << std::endl;

} // acc3 destroyed here

std::cout << "Total accounts after acc3 destroyed: "

<< BankAccount::getTotalAccounts() << std::endl;

return 0;

}Static member variables are declared inside the class but must be defined outside the class in a source file. They exist independently of any class instances—you can access them even if no objects of the class have been created. All objects of the class share the same static member variables, so modifying the static variable through one object affects what all other objects see. This makes static members perfect for tracking class-wide information like instance counts, shared configuration, or aggregate statistics across all instances.

Static member functions can be called without an object instance and can only access static member variables and other static member functions:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class Student {

private:

std::string name;

int id;

double gpa;

// Static members - shared across all students

static int nextID;

static std::vector<Student*> allStudents;

public:

Student(const std::string& studentName, double studentGPA)

: name(studentName), id(nextID++), gpa(studentGPA) {

allStudents.push_back(this);

std::cout << "Student created: " << name << " (ID: " << id << ")" << std::endl;

}

~Student() {

// Remove from allStudents when destroyed

for (auto it = allStudents.begin(); it != allStudents.end(); ++it) {

if (*it == this) {

allStudents.erase(it);

break;

}

}

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "ID: " << id << ", Name: " << name << ", GPA: " << gpa << std::endl;

}

double getGPA() const { return gpa; }

std::string getName() const { return name; }

// Static member function - no 'this' pointer

static void displayAllStudents() {

std::cout << "\n=== All Students ===" << std::endl;

for (const auto& student : allStudents) {

student->display();

}

}

static double calculateAverageGPA() {

if (allStudents.empty()) return 0.0;

double total = 0.0;

for (const auto& student : allStudents) {

total += student->gpa; // Access through pointer

}

return total / allStudents.size();

}

static int getStudentCount() {

return allStudents.size();

}

static Student* findTopStudent() {

if (allStudents.empty()) return nullptr;

Student* topStudent = allStudents[0];

for (const auto& student : allStudents) {

if (student->gpa > topStudent->gpa) {

topStudent = student;

}

}

return topStudent;

}

};

// Initialize static members

int Student::nextID = 1000;

std::vector<Student*> Student::allStudents;

int main() {

// Call static function without any Student objects

std::cout << "Initial student count: " << Student::getStudentCount() << std::endl;

Student s1("Alice Johnson", 3.8);

Student s2("Bob Smith", 3.5);

Student s3("Carol White", 3.9);

Student s4("David Brown", 3.2);

// Call static functions - note the ClassName:: syntax

Student::displayAllStudents();

std::cout << "\nTotal students: " << Student::getStudentCount() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Average GPA: " << Student::calculateAverageGPA() << std::endl;

Student* topStudent = Student::findTopStudent();

if (topStudent) {

std::cout << "Top student: " << topStudent->getName()

<< " (GPA: " << topStudent->getGPA() << ")" << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}Static member functions are called using the class name rather than an object instance, though they can also be called through an object. Since they don’t have a this pointer, they cannot access non-static member variables or call non-static member functions directly. They can only work with static members or with objects passed as parameters. This makes static member functions useful for operations that relate to the class as a whole rather than to individual instances, such as factory functions, utility functions, or operations on collections of all instances.

Let me show you a comprehensive example demonstrating static variables in a realistic application:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <ctime>

class Logger {

private:

std::string component;

// Static members for logging configuration and statistics

static int messageCount;

static bool loggingEnabled;

static std::vector<std::string> logHistory;

// Static function to format timestamp

static std::string getCurrentTimestamp() {

time_t now = time(nullptr);

char buffer[26];

struct tm* timeinfo = localtime(&now);

strftime(buffer, sizeof(buffer), "%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S", timeinfo);

return std::string(buffer);

}

public:

Logger(const std::string& comp) : component(comp) {}

void log(const std::string& message) {

if (!loggingEnabled) {

return; // Logging disabled globally

}

messageCount++; // Increment static counter

std::string logEntry = "[" + getCurrentTimestamp() + "] " +

"[" + component + "] " + message;

std::cout << logEntry << std::endl;

// Store in history (static vector shared by all Logger instances)

logHistory.push_back(logEntry);

}

// Static functions to control logging behavior

static void enableLogging() {

loggingEnabled = true;

std::cout << "Logging enabled" << std::endl;

}

static void disableLogging() {

loggingEnabled = false;

std::cout << "Logging disabled" << std::endl;

}

static int getMessageCount() {

return messageCount;

}

static void displayHistory() {

std::cout << "\n=== Log History ===" << std::endl;

for (const auto& entry : logHistory) {

std::cout << entry << std::endl;

}

}

static void clearHistory() {

logHistory.clear();

messageCount = 0;

std::cout << "Log history cleared" << std::endl;

}

};

// Initialize static members

int Logger::messageCount = 0;

bool Logger::loggingEnabled = true;

std::vector<std::string> Logger::logHistory;

class ConnectionPool {

private:

std::string poolName;

int activeConnections;

// Static members for pool management

static int totalPools;

static int maxConnectionsPerPool;

static int globalActiveConnections;

public:

ConnectionPool(const std::string& name)

: poolName(name), activeConnections(0) {

totalPools++;

std::cout << "Connection pool '" << poolName << "' created. Total pools: "

<< totalPools << std::endl;

}

~ConnectionPool() {

totalPools--;

globalActiveConnections -= activeConnections;

}

bool acquireConnection() {

if (activeConnections >= maxConnectionsPerPool) {

std::cout << "Pool '" << poolName << "' at maximum capacity" << std::endl;

return false;

}

activeConnections++;

globalActiveConnections++;

std::cout << "Connection acquired from pool '" << poolName

<< "'. Active: " << activeConnections << std::endl;

return true;

}

void releaseConnection() {

if (activeConnections > 0) {

activeConnections--;

globalActiveConnections--;

std::cout << "Connection released to pool '" << poolName

<< "'. Active: " << activeConnections << std::endl;

}

}

// Static functions for global pool management

static int getTotalPools() {

return totalPools;

}

static int getGlobalActiveConnections() {

return globalActiveConnections;

}

static void setMaxConnectionsPerPool(int max) {

maxConnectionsPerPool = max;

std::cout << "Maximum connections per pool set to: " << max << std::endl;

}

static void displayGlobalStats() {

std::cout << "\n=== Global Pool Statistics ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Total pools: " << totalPools << std::endl;

std::cout << "Global active connections: " << globalActiveConnections << std::endl;

std::cout << "Max connections per pool: " << maxConnectionsPerPool << std::endl;

}

};

// Initialize static members

int ConnectionPool::totalPools = 0;

int ConnectionPool::maxConnectionsPerPool = 5;

int ConnectionPool::globalActiveConnections = 0;

int main() {

std::cout << "=== Logger Demonstration ===" << std::endl;

Logger appLogger("Application");

Logger dbLogger("Database");

appLogger.log("Application started");

dbLogger.log("Database connected");

appLogger.log("Processing request");

std::cout << "\nTotal messages logged: " << Logger::getMessageCount() << std::endl;

Logger::disableLogging();

appLogger.log("This won't be logged");

Logger::enableLogging();

dbLogger.log("Database query executed");

Logger::displayHistory();

std::cout << "\n=== Connection Pool Demonstration ===" << std::endl;

ConnectionPool::setMaxConnectionsPerPool(3);

ConnectionPool pool1("Primary");

ConnectionPool pool2("Secondary");

pool1.acquireConnection();

pool1.acquireConnection();

pool2.acquireConnection();

ConnectionPool::displayGlobalStats();

pool1.releaseConnection();

ConnectionPool::displayGlobalStats();

return 0;

}This comprehensive example demonstrates static variables at multiple levels. The Logger class uses static members to track message counts and maintain shared log history across all Logger instances, with static functions controlling global logging behavior. The ConnectionPool class uses static members to track total pools and enforce global connection limits, with static functions providing system-wide statistics. Each class uses static appropriately—for data and behavior that logically belongs to the class itself rather than to individual instances.

Initialization order of static variables within a single compilation unit is well-defined—they’re initialized in the order they’re declared. However, initialization order across different compilation units is undefined, which can cause subtle bugs:

// File1.cpp

int globalValue = computeValue(); // When does this initialize?

// File2.cpp

extern int globalValue;

int dependent = globalValue + 10; // Undefined order - might use uninitialized globalValue!To avoid initialization order problems, prefer local static variables over global statics when possible, or use initialization-on-first-use patterns:

#include <iostream>

class Config {

private:

int value;

public:

Config() : value(42) {

std::cout << "Config initialized" << std::endl;

}

int getValue() const { return value; }

};

// Initialization-on-first-use pattern - avoids initialization order problems

Config& getConfig() {

static Config instance; // Initialized on first call, guaranteed

return instance;

}

void useConfig() {

std::cout << "Config value: " << getConfig().getValue() << std::endl;

}

int main() {

useConfig(); // Config initialized here on first use

useConfig(); // Uses existing instance

return 0;

}The initialization-on-first-use pattern using a static local variable ensures the object is initialized the first time the function is called, regardless of when that happens. This eliminates initialization order dependencies and is thread-safe in C++11 and later.

Static variables in namespace scope (file scope) have internal linkage by default when declared static, meaning they’re visible only within that translation unit:

// In header file: utils.h

namespace Utils {

static int counter = 0; // Each translation unit including this gets its own copy!

}

// Better approach - use unnamed namespace for internal linkage

namespace {

int counter = 0; // Internal linkage, one per translation unit

}

// Or use inline for shared variable across translation units (C++17)

inline int sharedCounter = 0; // Same variable in all translation unitsThe static keyword at file scope is largely obsolete in modern C++—use unnamed namespaces for internal linkage or inline variables for shared state across translation units.

Understanding when to use static variables requires balancing their benefits against potential drawbacks. Static variables are excellent for maintaining state between function calls without global variables, tracking class-wide statistics, implementing singleton patterns, and caching expensive computations. However, they can make testing harder because they maintain state across tests, can create thread-safety issues in multithreaded programs, and can make code harder to reason about because state persists in non-obvious ways.

Common mistakes with static variables include forgetting to define static member variables outside the class, attempting to access non-static members from static functions, depending on undefined initialization order across translation units, and overusing static when simpler alternatives exist. Another subtle error is assuming static local variables are thread-safe in older C++ standards—they’re only guaranteed thread-safe initialization in C++11 and later.

Key Takeaways

The static keyword fundamentally changes variable lifetime and visibility, creating variables that persist beyond normal scope rules. Static local variables inside functions maintain their values between function calls, being initialized once on first execution and persisting until program termination. This enables patterns like counters, caches, and unique ID generators without resorting to global variables while keeping the variable properly scoped within the function.

Static member variables belong to the class itself rather than individual instances, creating shared state among all objects of the class. They must be declared inside the class and defined outside the class in a source file, and they exist independently of any class instances. Static member functions can be called without object instances but can only access static members, making them suitable for operations that relate to the class as a whole rather than to individual instances.

The initialization-on-first-use pattern with static local variables solves initialization order problems and provides thread-safe lazy initialization in C++11 and later. Static variables should be used judiciously—they’re powerful for maintaining appropriate persistent state but can make code harder to test and reason about. Understanding static variables enables writing cleaner code that maintains state exactly where needed without unnecessary global variables while properly expressing class-wide concepts through static members.