Introduction

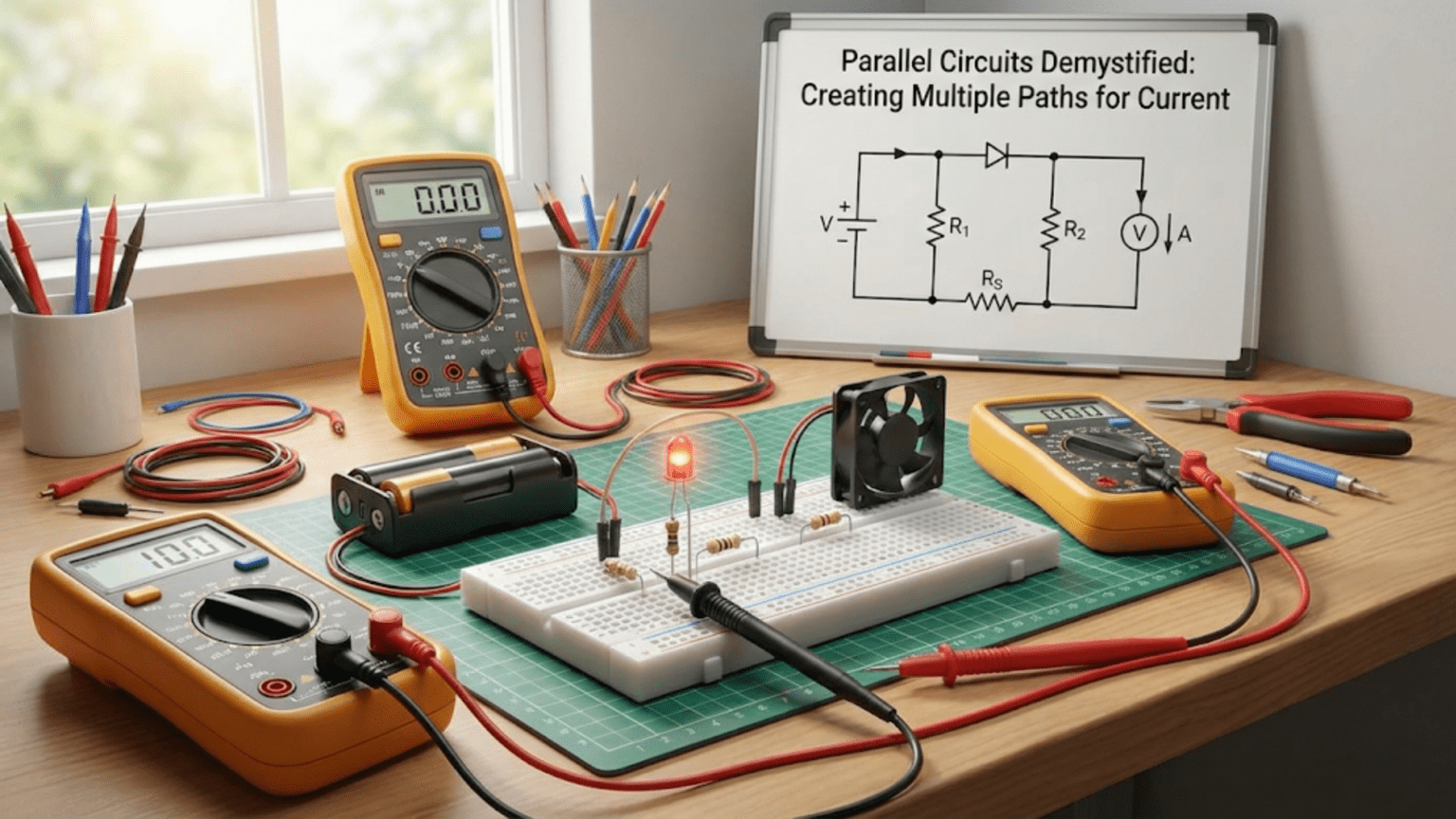

When components connect to the same two points in a circuit, providing multiple simultaneous paths for current flow, they form a parallel circuit—the second fundamental circuit configuration alongside series circuits. While series circuits are often intuitive because they mirror our everyday experience of sequential processes, parallel circuits initially seem more abstract to many beginners. Yet parallel circuits are actually more common in practical applications than series circuits, appearing in everything from household electrical wiring to computer power distribution to automotive electrical systems.

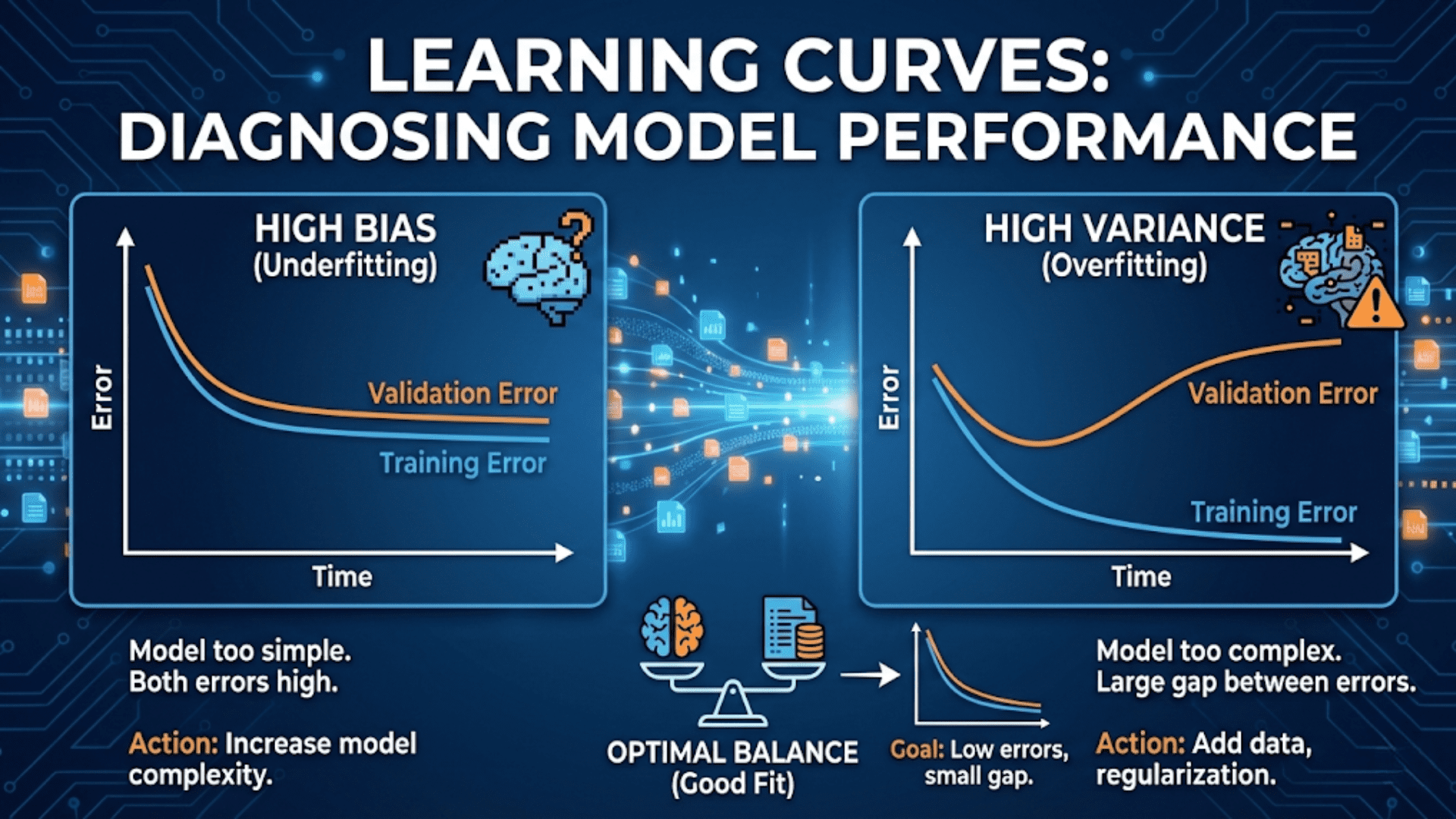

Understanding parallel circuits is essential because they behave fundamentally differently from series circuits in ways that profoundly affect circuit design and analysis. Where series circuits have identical current through all components with divided voltage, parallel circuits have identical voltage across all components with divided current. Where series resistance adds directly, parallel resistance combines through reciprocals in a way that always produces less total resistance than any individual branch. These opposite characteristics make parallel circuits the perfect complement to series circuits in the circuit designer’s toolkit.

The applications of parallel circuits extend throughout electronics. Your home’s electrical outlets all connect in parallel, ensuring each device receives full line voltage regardless of what other devices are connected. LED arrays use parallel strings to increase brightness while maintaining voltage compatibility. Battery banks parallel cells to increase capacity. Power distribution systems use parallel connections to supply multiple loads. Every one of these applications relies on parallel circuit characteristics that you must understand thoroughly to work effectively with real circuits.

This comprehensive guide will build your understanding of parallel circuits from fundamental principles through practical applications. We will explore why parallel circuits behave as they do, develop mathematical competence in parallel circuit calculations, and cultivate intuitive understanding that lets you predict parallel circuit behavior and design parallel configurations confidently.

The Defining Characteristic: Multiple Current Paths

Understanding what makes a circuit “parallel” requires examining how current can flow through multiple simultaneous paths.

Multiple Simultaneous Paths

In a parallel circuit, current flowing from the power source encounters junction points where it can divide among multiple paths, flow through those separate paths simultaneously, and then recombine before returning to the source. Each path provides an independent route from one circuit point to another, with current choosing to flow through multiple paths simultaneously rather than being forced through a single series path.

This multiple-path characteristic means placing your finger on one component and tracing to the second connection point could follow multiple different routes through different components. Unlike series circuits where only one path exists, parallel circuits offer choices at junction points where current splits among available paths.

Recognizing parallel connections in complex circuits requires identifying these junction points where current can divide and where it recombines. Even in circuits containing series and parallel elements, you can identify sections where multiple components connect in parallel with each other, sharing the same voltage despite the larger circuit having series elements elsewhere.

The Fundamental Consequence: Identical Voltage

The most important consequence of parallel connection is that all components in parallel experience identical voltage across their terminals. If 12 volts appears across one resistor in a parallel group, exactly 12 volts appears across every other component in that parallel group. This is an absolute requirement based on the definition of voltage and the physical laws governing electric potential.

Voltage represents the potential difference between two points. If multiple components connect to the same two points, they all experience the same potential difference by definition. There is only one voltage between any two specific points in a circuit at any moment, so all components bridging those points must have that voltage across them.

This voltage equality makes certain parallel circuit calculations straightforward. Once you know voltage across one parallel component, you know voltage across all parallel components—the same value applies throughout the parallel group. You need not calculate voltage separately for each component in parallel.

Current Division: The Corollary

While voltage remains constant across parallel components, current divides among them. The total current flowing into a parallel junction equals the sum of currents flowing through all parallel branches. If 10 amps enters a junction and three parallel paths exist, those paths carry currents that sum to 10 amps—perhaps 2A, 3A, and 5A, or any other combination totaling 10A.

How current divides among parallel branches depends on branch resistances. Lower resistance branches carry more current; higher resistance branches carry less current. Current divides inversely proportional to resistance—a branch with half the resistance of another carries twice the current. This inverse relationship flows directly from Ohm’s Law: with voltage constant, current must be inversely proportional to resistance (I = V/R).

This current division means parallel circuits can supply different current demands simultaneously while maintaining constant voltage. This is why household wiring uses parallel connections: each outlet provides full line voltage while individual devices draw whatever current they require, with total current being the sum of individual device currents.

Voltage Characteristics in Parallel Circuits

While parallel circuit voltage behavior is simpler than series circuits, understanding its implications matters for practical circuit work.

Constant Voltage Across All Components

Every component in a parallel group experiences the full voltage across that group. A 9V battery with three resistors connected in parallel provides 9V across each resistor simultaneously. This differs fundamentally from series circuits where voltage divides among components.

This constant voltage has important implications. Each parallel component operates at full voltage regardless of other components present. Adding or removing parallel components does not affect voltage across remaining components—they continue receiving the same voltage. This independence makes parallel circuits more modular than series circuits, where adding or removing components affects voltage across all series components.

For loads requiring specific voltage, parallel connection ensures they receive that voltage. Multiple LEDs connected in parallel each receive full supply voltage, unlike series LEDs where voltage divides among them. Multiple circuits powered from a common supply all receive the same supply voltage despite different current demands.

Implications for Power Distribution

The constant voltage characteristic makes parallel circuits ideal for power distribution. Your home’s electrical system uses parallel connections throughout: all outlets on a circuit receive the same voltage regardless of how many devices plug in. Each device operates at its rated voltage, drawing whatever current it requires.

This parallel distribution means devices operate independently. Turning on your refrigerator does not change voltage at your computer—both receive full line voltage. The refrigerator’s current adds to total circuit current, but voltage remains constant (assuming adequate wire sizing and proper electrical installation).

Source Voltage Regulation

While parallel connection maintains constant voltage across loads, the source must provide whatever current the parallel loads demand. If parallel loads collectively demand more current than the source can supply, source voltage sags under excessive load. This is why circuit breakers limit total current on each circuit—ensuring parallel loads cannot collectively overload the supply.

A properly designed parallel circuit has source capacity exceeding maximum expected parallel load. The source maintains voltage within specified tolerance across all expected load conditions. If loads can vary independently, source capacity must accommodate maximum possible total current demand when all loads draw peak current simultaneously.

Parallel Resistance: The Reciprocal Relationship

Calculating total resistance of parallel resistors requires understanding reciprocal mathematics that initially seems counterintuitive but follows logically from parallel circuit characteristics.

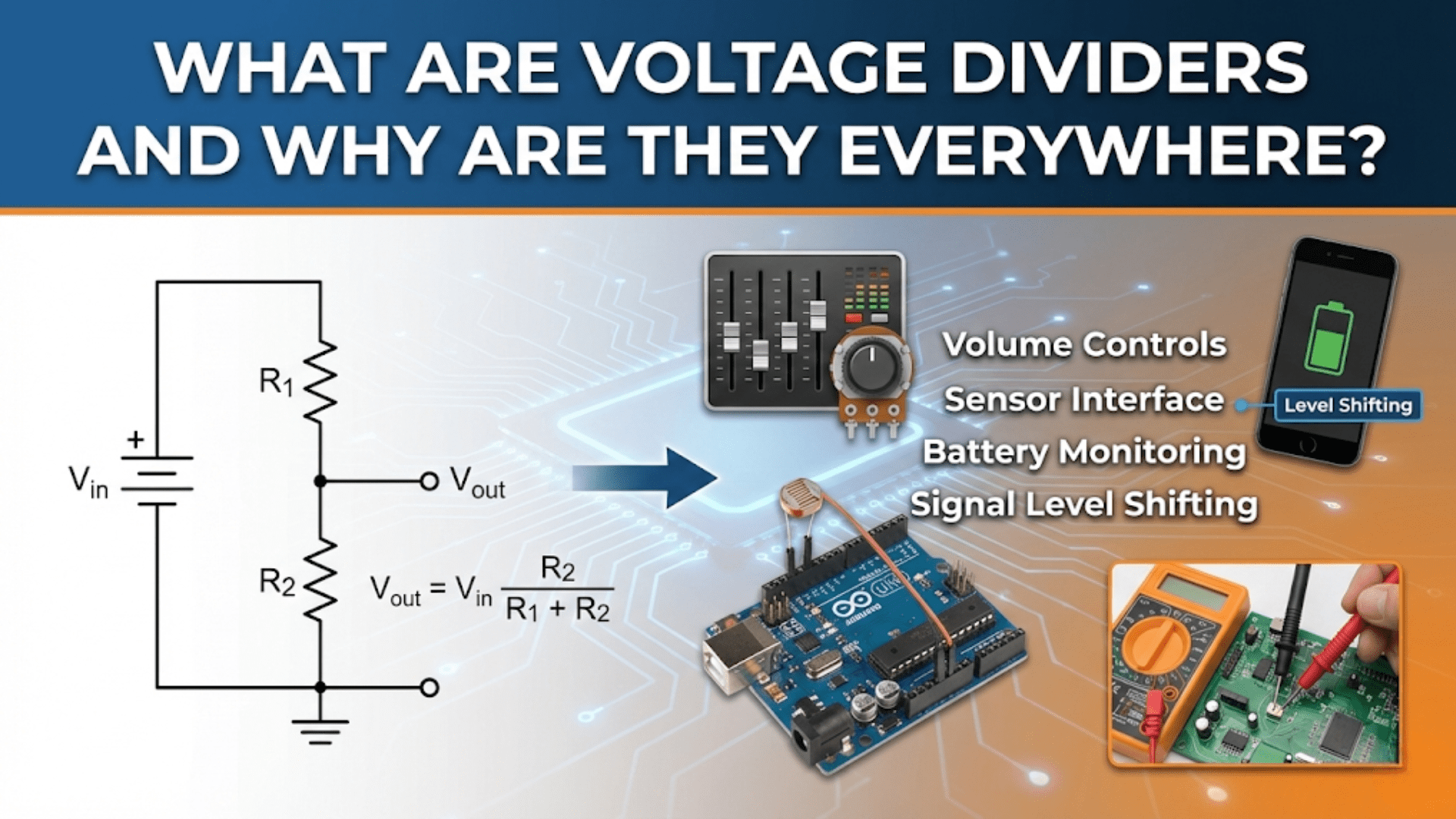

The Reciprocal Formula

For resistors R1, R2, R3, etc., connected in parallel, total resistance R_total satisfies: 1/R_total = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3 + … . This reciprocal formula is more complex than series resistance (simple addition) but follows necessarily from parallel circuit behavior.

The physical reason is that parallel resistors provide multiple simultaneous current paths. More paths mean more total current for a given voltage, which means lower total resistance. Each additional parallel resistor adds another current path, decreasing total resistance. The reciprocal formula quantifies this: adding terms to the right side increases the sum, which decreases R_total when you take the reciprocal.

A critical insight: parallel resistance is always less than the smallest individual resistance in the parallel group. Adding any resistor in parallel decreases total resistance. This seems counterintuitive if you think “adding resistors should increase resistance,” but parallel connection adds current paths, not resistances in series.

Two Resistors in Parallel: Simplified Formula

For two resistors in parallel, the reciprocal formula simplifies to: R_total = (R1 × R2) / (R1 + R2). This product-over-sum formula is easier to calculate than the general reciprocal formula. For example, 100Ω and 200Ω in parallel: R_total = (100 × 200) / (100 + 200) = 20,000 / 300 = 66.7Ω.

Notice the result (66.7Ω) is less than either resistor individually. Also notice it is closer to the smaller resistor (100Ω) than the larger one (200Ω). This pattern holds generally: parallel resistance approaches the smallest individual resistance as you add more parallel resistors, because the smallest resistance dominates current flow.

Equal Resistors in Parallel

When n identical resistors of value R connect in parallel, total resistance equals R/n. Two equal resistors in parallel have half the resistance of one resistor. Three equal resistors have one-third the resistance. This simple relationship makes calculating equal-resistor parallel groups trivial.

This relationship shows that parallel connection can create resistance values smaller than available resistor values. Need a 50Ω resistor but only have 100Ω resistors? Connect two in parallel. Need 33Ω but only have 100Ω? Three in parallel give 33.3Ω, close enough for many applications.

Calculating Current from Parallel Resistance

Once you know total parallel resistance, calculating total current uses Ohm’s Law: I_total = V / R_total. For parallel resistors of 100Ω, 200Ω, and 300Ω across 12V, total resistance is 54.5Ω (calculated using reciprocal formula), and total current is 12V / 54.5Ω = 0.22A = 220mA.

This total current divides among branches. The 100Ω resistor carries 12V / 100Ω = 120mA. The 200Ω resistor carries 12V / 200Ω = 60mA. The 300Ω resistor carries 12V / 300Ω = 40mA. These branch currents sum to 220mA, confirming our total current calculation (within rounding error).

Conductance: An Alternative Perspective

Conductance, measured in siemens (S), equals the reciprocal of resistance: G = 1/R. For parallel circuits, conductances add directly: G_total = G1 + G2 + G3 + … . This direct addition mirrors series resistance addition, making parallel calculations simpler in conductance terms.

While most circuit analysis uses resistance rather than conductance, thinking in conductance terms can clarify parallel behavior. Parallel paths add current-carrying capability (conductance) rather than adding resistance. The reciprocal formula for resistance reflects this conductance addition: when you add conductances (reciprocals of resistances), you must then take the reciprocal again to get back to resistance.

Current Division in Parallel Circuits

Understanding how current divides among parallel branches is essential for analyzing and designing parallel circuits.

The Inverse Proportion Principle

Current divides among parallel branches inversely proportional to their resistances. A branch with half the resistance of another carries twice the current. A branch with three times the resistance carries one-third the current. This inverse relationship follows directly from Ohm’s Law: I = V/R, with V constant for all parallel branches.

For two parallel resistors carrying total current I_total, the current through each resistor is:

- I1 = I_total × (R2 / (R1 + R2))

- I2 = I_total × (R1 / (R1 + R2))

Notice that I1 depends on R2 and I2 depends on R1—this counter-intuitive reciprocal relationship reflects the inverse proportion. The current through R1 increases when R2 decreases because more total current flows (due to lower total resistance) and R1’s share of that current increases.

Current Division Applications

Current division enables sharing loads among multiple parallel paths. Power distribution uses parallel conductors to share current, preventing any single conductor from overheating. Battery paralleling shares discharge current among cells, extending total available capacity. Current mirrors in analog circuits use controlled current division to route precise currents to multiple circuits.

Understanding current division helps predict circuit behavior. If you parallel a 100Ω resistor with a 10Ω resistor, the 10Ω resistor carries ten times the current despite both experiencing the same voltage. The 10Ω resistor must have power rating ten times higher (at least) to avoid overheating, even though voltage is identical.

Current Division Accuracy

Current division equations assume ideal resistors with precisely known values. Real resistors have tolerances (typically 5% or 10%) that affect how current actually divides. Two “identical” 100Ω resistors might actually be 95Ω and 105Ω due to tolerance, causing current to divide unequally (slightly more through the 95Ω resistor).

For applications requiring precise current sharing, use precision resistors with tight tolerances (1% or better), or use active current regulation that enforces equal current regardless of resistance variations. Current sharing among parallel power supplies often requires active current-share circuits because passive resistance matching alone cannot achieve adequate balance.

Power Dissipation in Parallel Circuits

Power dissipation patterns in parallel circuits differ from series circuits due to constant voltage across parallel components.

Individual Component Power

Each component in a parallel circuit dissipates power according to P = V²/R, where V is the voltage (same for all parallel components) and R is that component’s resistance. Since voltage is constant throughout the parallel group, components with lower resistance dissipate more power.

For our previous example (100Ω, 200Ω, and 300Ω resistors across 12V), power dissipations are:

- 100Ω resistor: P = (12V)² / 100Ω = 1.44W

- 200Ω resistor: P = (12V)² / 200Ω = 0.72W

- 300Ω resistor: P = (12V)² / 300Ω = 0.48W

The 100Ω resistor dissipates three times the power of the 300Ω resistor despite experiencing the same voltage, because it has one-third the resistance and therefore carries three times the current. The P = V²/R relationship shows power inversely proportional to resistance for constant voltage.

Total Circuit Power

Total power dissipated in a parallel circuit equals the sum of individual component power dissipations, or equivalently, equals voltage squared divided by total parallel resistance: P_total = V² / R_total. For our example, total power is (12V)² / 54.5Ω = 2.64W, which equals the sum of individual power dissipations (1.44W + 0.72W + 0.48W = 2.64W).

This total power comes from the power source. The source delivers power at rate P = V × I_total, where I_total is the sum of all branch currents. Since I_total = V / R_total, we get P = V × (V / R_total) = V² / R_total, confirming the power calculation.

Power Considerations in Parallel Design

When paralleling components for increased power handling, the parallel combination’s power capability equals the sum of individual component ratings. Four 1W resistors in parallel can safely dissipate 4W total (assuming adequate cooling and proper thermal design). This makes paralleling useful for creating higher-power-rated components from lower-rated units.

However, current sharing matters critically for power handling. If resistance variations cause unequal current sharing, the component carrying more current dissipates more power and may overheat even though total power remains within rating. For reliable high-power parallel operation, match component values carefully and verify current sharing under actual operating conditions.

Parallel Circuit Applications

Parallel connections enable numerous practical applications that series connections cannot provide.

Power Distribution Systems

All power distribution uses parallel connections to supply multiple loads. Your home’s outlets connect in parallel from the circuit breaker panel. Each outlet provides full line voltage, and devices plugged into any outlet draw their required current without affecting voltage at other outlets (assuming proper wire sizing and adequate circuit capacity).

This parallel distribution allows independent operation of multiple devices. Your lights, appliances, electronics, and HVAC equipment all operate simultaneously at their rated voltages despite vastly different current demands. The circuit breaker limits total current, ensuring parallel loads cannot collectively exceed safe wire capacity.

Battery Paralleling for Increased Capacity

Connecting batteries in parallel increases total capacity (amp-hours) while maintaining voltage. Two 12V 100Ah batteries in parallel provide 12V at 200Ah capacity. Discharge current divides between batteries based on their internal resistances, ideally equally if batteries are matched.

For safe battery paralleling, use identical battery types, ages, and charge states. Connect positive terminals together and negative terminals together using equal-length cables to each battery. This ensures equal resistance in each battery’s connection, promoting equal current sharing. Never parallel batteries of significantly different voltages—current will flow from higher voltage to lower voltage, potentially causing dangerous overheating.

LED Arrays and Parallel Strings

LED displays and illumination systems often use parallel strings of LEDs. Each string operates at its required current with proper current limiting, and parallel connection increases total brightness without requiring higher voltage. If one string fails open, other strings continue operating—a significant reliability advantage over series-connected LEDs where any single failure disables the entire string.

Each parallel LED string requires its own current-limiting resistor or current regulator. Sharing a single current limiter among parallel LED strings causes unequal current sharing due to LED forward voltage variations, leading to uneven brightness and potential LED damage.

Redundancy and Reliability

Parallel connection provides reliability through redundancy. If one parallel component fails open, current continues flowing through remaining parallel paths. The system continues operating, though often at reduced capacity. This graceful degradation is preferable to the complete failure that occurs when a series component fails open.

Many critical systems use parallel redundancy: multiple parallel power supplies, redundant data paths, parallel sensors for voting logic. The parallel configuration ensures that single-point failures do not completely disable the system, improving overall reliability despite increased complexity.

Current Multiplication

Sometimes parallel connection serves to increase current capability. Power semiconductors often parallel to handle higher current than any single device can manage. Multiple parallel MOSFETs share load current, with each carrying a fraction of the total. This parallel operation requires careful matching and sometimes active current-sharing circuits to ensure even distribution.

Paralleling for current multiplication works best when component characteristics closely match. For power semiconductors, devices from the same manufacturing lot often match well enough for passive parallel operation. Devices from different lots may require additional circuitry to force equal current sharing.

Analyzing More Complex Parallel Circuits

Real parallel circuits often contain more than just resistors, requiring expanded analysis techniques.

Parallel Switches

Switches connected in parallel create OR logic: if any switch closes, current flows. This configuration provides multiple control points for a single load. Stairway lighting uses parallel switches at both ends—either switch can control the light (though practical implementations use more sophisticated three-way switches).

Parallel switches provide redundant activation. Emergency systems might use parallel switches at multiple locations, allowing operation from any position. The first switch to close completes the circuit; additional switches closing have no further effect.

Parallel Current Sources

Current sources connected in parallel add their currents. Two 1mA current sources in parallel provide 2mA to the load. This current addition contrasts with voltage sources, where parallel connection ideally maintains the source voltage but can cause problems if voltages differ even slightly.

Paralleling voltage sources requires matching voltages extremely closely or implementing active current-sharing circuits. Even small voltage differences between parallel voltage sources cause large circulating currents between sources, potentially causing damage. Paralleling voltage sources safely requires special techniques beyond simple parallel connection.

Parallel Capacitors

Capacitors in parallel add directly: C_total = C1 + C2 + C3 + … . This simple addition makes parallel capacitor combinations easy to calculate. The parallel connection increases total capacitance while maintaining the same voltage rating as individual capacitors.

Parallel capacitor connections appear in power supply filtering, where multiple capacitors provide low impedance across broad frequency ranges. Different capacitor types and values optimize for different frequencies, with the parallel combination providing superior performance compared to any single capacitor.

Parallel Inductors

Inductors in parallel combine like resistors in parallel (using reciprocals): 1/L_total = 1/L1 + 1/L2 + 1/L3 + … . This reciprocal combination means parallel inductance is less than the smallest individual inductance, similar to parallel resistance.

However, mutual inductance between physically close inductors affects total inductance unpredictably. Magnetic coupling can cause parallel inductance to differ significantly from the calculated reciprocal value. For predictable results, physically separate parallel inductors or use magnetic shielding to minimize coupling.

Common Parallel Circuit Mistakes

Several errors appear repeatedly in beginner’s parallel circuit analysis and design.

Forgetting That Voltage Is Constant

The most common mistake is calculating different voltages for different parallel components. Since voltage is identical across all parallel components, calculating it once gives the value for all components. Applying voltage divider equations to parallel circuits is incorrect—voltage dividers apply only to series circuits.

This mistake often leads to incorrect current calculations. If you use wrong voltage for a component, your current calculation (I = V/R) will be wrong, propagating errors through subsequent power and energy calculations. Always remember: parallel means equal voltage.

Using Series Resistance Formula

Confusing parallel resistance calculation (reciprocals) with series resistance calculation (direct addition) is a common error. Remember: parallel resistances combine through reciprocals; series resistances add directly. The formulas are fundamentally different and not interchangeable.

A memory aid: parallel paths provide multiple routes for current (like parallel roads), and more routes mean lower total resistance (reciprocal formula gives result less than smallest individual value). Series paths force current through all resistances in sequence (like obstacles in series), and more obstacles mean more total resistance (simple addition).

Incorrect Current Division Calculations

When dividing current among parallel branches, some beginners calculate proportionally to resistance rather than inversely proportional. Remember: current divides inversely to resistance. Lower resistance carries more current; higher resistance carries less current. The branch with half the resistance carries twice the current, not half the current.

Using the current divider formula correctly requires attention to which resistance appears in numerator versus denominator. Double-check calculations by verifying that branch currents sum to total current—this catches most current division errors.

Assuming Perfect Current Sharing

Real parallel components never share current perfectly equally unless they are precisely matched. Tolerance variations cause unequal current sharing, sometimes significantly. For applications requiring equal current sharing (parallel power devices, parallel batteries, LED strings), design must account for variations or implement active current balancing.

Assuming equal sharing when designing parallel configurations for increased current capacity can lead to individual component overload even though total current remains within rating. Always consider worst-case current sharing based on component tolerances.

Paralleling Mismatched Components

Paralleling components with significantly different characteristics causes problems. Paralleling a 1Ω resistor with a 1kΩ resistor creates a combination dominated by the 1Ω resistor—the 1kΩ resistor contributes negligibly to current capacity. Similarly, paralleling batteries of different voltages or capacities causes unequal current sharing that can damage components.

For effective paralleling, use components with similar characteristics. Resistors should be within the same decade of resistance. Batteries should be identical type, age, and charge state. Capacitors should be similar values and types. Large characteristic mismatches defeat the purpose of paralleling.

Parallel Circuit Troubleshooting

When parallel circuits malfunction, systematic troubleshooting identifies problems efficiently.

One Branch Not Working

When one parallel branch stops conducting while others work normally, that branch contains an open circuit or has developed very high resistance. Other branches continue operating normally at full voltage because parallel connection isolates branch faults.

Measure voltage across the non-functioning branch—it should equal voltage across working branches. If voltage is present but current is zero, the branch contains an open circuit. Check each component and connection in that branch for opens. A broken wire, cold solder joint, or failed component creates the open.

Excessive Total Current

If parallel circuit draws more current than expected, total parallel resistance is lower than calculated. This might result from short circuits in branches, wrong component values, or unintended parallel paths. Measure resistance across the parallel combination with power removed. Compare measured resistance to calculated value.

If measured resistance is much lower than calculated, some branch has lower resistance than expected. Isolate branches and measure each individually to identify which has incorrect resistance. This systematic isolation identifies the problem branch without testing every component.

Voltage Lower Than Expected

If voltage across parallel loads is lower than expected, either the source cannot supply required current (source voltage sagging under load) or resistance exists in series with the parallel combination (wire resistance or connection resistance causing voltage drop). Measure source voltage without load—if it measures correctly, series resistance is the problem. If source voltage sags under load, source capacity is inadequate.

Adequate wire sizing prevents series voltage drops from degrading parallel circuit voltage. If voltage at the source is correct but voltage at parallel loads is low, measure voltage drop in connecting wires. Excessive drop indicates undersized wires or poor connections.

Intermittent Parallel Branch

When a parallel branch works intermittently, suspect poor connections in that branch. Cold solder joints, loose terminals, or corroded contacts cause intermittent conductivity. Other branches continue working during intermittent failures, helping isolate the problem to the specific branch.

Flexing wires or tapping components while monitoring circuit operation may reveal intermittent connections by triggering failures. Once identified, repair involves remaking connections, resoldering joints, or replacing damaged components.

Parallel Circuits in Practical Applications

Understanding how real applications use parallel circuits reinforces theoretical knowledge.

Household Electrical Systems

Your home’s electrical system exemplifies parallel circuit application. Every outlet on a circuit connects in parallel with others. Light fixtures, appliances, and electronics all receive full line voltage regardless of what else operates. Each device draws its required current, with total circuit current being the sum.

Circuit breakers protect parallel circuits by limiting total current. The breaker rating ensures total parallel load cannot exceed safe wire capacity. When too many devices operate simultaneously, exceeding breaker rating, the breaker trips and opens the circuit, protecting the wiring from overheating.

Automotive Electrical Systems

Vehicle electrical systems use extensive parallel wiring. All 12V accessories connect in parallel to the battery, receiving full battery voltage. Lights, radio, power windows, and other loads operate independently, each drawing required current. Fuses protect individual circuits, allowing most loads to continue functioning even if one circuit fails.

The alternator maintains battery voltage despite varying load demands. As parallel loads switch on and off, alternator output adjusts to maintain system voltage, demonstrating the supply regulation required for parallel distribution systems.

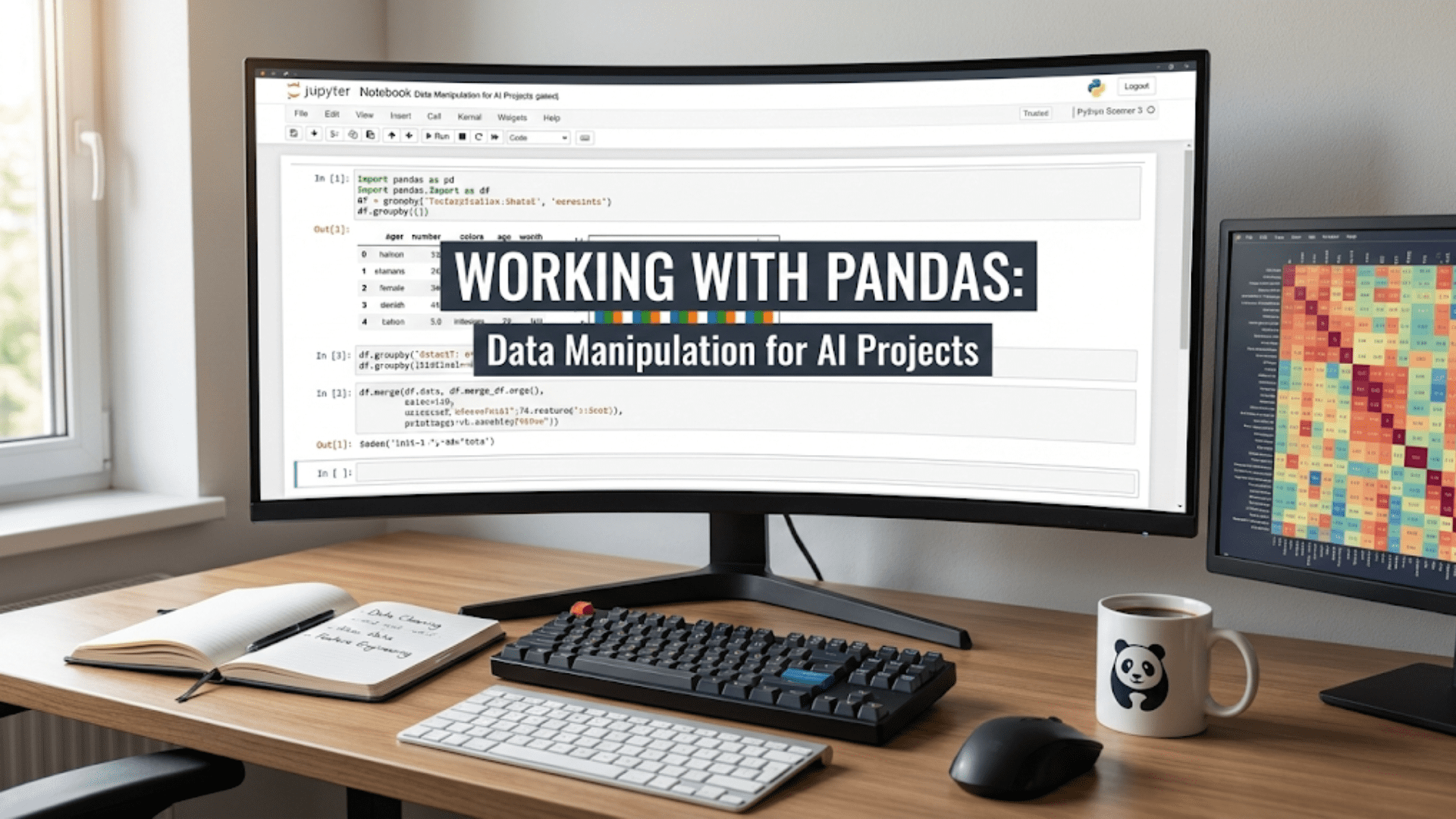

Computer Power Distribution

Inside computers, the power supply provides parallel connections to motherboard, drives, and peripherals. All components receive specified voltages (typically +12V, +5V, +3.3V) regardless of load variations. The power supply regulates voltage actively, compensating for load changes to maintain specified voltages.

The motherboard distributes power to processor, memory, and other components using parallel distribution. Decoupling capacitors in parallel with load points provide local current during rapid transients, ensuring voltage stability despite fast load changes.

Series-Parallel Combinations

Most practical circuits combine series and parallel elements, requiring systematic analysis that applies both series and parallel principles.

Identifying Series and Parallel Sections

The first step in analyzing series-parallel circuits is identifying which components are in series and which are in parallel. Start at the power source and trace current paths. Where current has only one path, components are in series. Where current can divide among multiple paths, components are in parallel.

Mark series groups and parallel groups explicitly before calculating. This prevents confusion about which formula (series addition or parallel reciprocal) to apply to which components. Many errors in series-parallel analysis result from applying the wrong formula to a component group.

Systematic Reduction Method

Analyze series-parallel circuits by systematically simplifying—replace series groups with equivalent resistances, then replace parallel groups with equivalent resistances, repeating until you reduce the circuit to a single equivalent resistance. Then work backward, calculating currents and voltages throughout the original circuit.

This systematic approach, sometimes called the ladder method, works reliably for any resistive circuit that can be drawn as series-parallel combinations. Not all circuits can be simplified this way (bridge circuits and networks require more advanced techniques), but most practical circuits yield to systematic series-parallel analysis.

Conclusion: Complementary to Series Circuits

Parallel circuits represent the second fundamental circuit configuration, exhibiting characteristics that complement series circuits perfectly. Where series circuits have constant current with divided voltage, parallel circuits have constant voltage with divided current. Where series resistance adds directly, parallel resistance combines through reciprocals. These opposite characteristics make parallel and series circuits complementary tools for circuit design.

Understanding both series and parallel circuits thoroughly enables analysis of any passive circuit. Most practical circuits combine series and parallel elements, requiring you to recognize which sections are series and which are parallel, then apply appropriate analysis techniques to each section. This combined knowledge forms the foundation for all circuit analysis work.

The practical applications of parallel circuits are vast: power distribution, battery paralleling, LED arrays, redundant systems, current multiplication. Every application exploits parallel circuit characteristics—constant voltage across branches, current division among paths, total resistance less than any individual branch. When you see components connected to the same two points in a schematic, immediately recognize them as parallel components and consider the implications for voltage, current division, and power dissipation.

Common mistakes in parallel circuit analysis—forgetting that voltage is constant, using series formulas, incorrect current division, assuming perfect current sharing, paralleling mismatched components—can be avoided through systematic application of parallel circuit principles. Always verify that parallel components experience the same voltage, that current divides according to the inverse proportion principle, and that branch currents sum to total current.

Troubleshooting parallel circuits requires understanding their tolerance of single-branch failures. Unlike series circuits where any open stops all current, parallel circuits continue operating when one branch fails open. This resilience aids troubleshooting by isolating problems to specific branches, but it also means parallel circuits can partially fail without obvious symptoms until multiple branches fail or total current exceeds safe limits.

Parallel circuits provide the second pillar supporting all circuit analysis. Combined with series circuit knowledge, parallel circuit understanding enables you to analyze any passive circuit, design voltage dividers and current distributors, select appropriate component configurations, and troubleshoot problems systematically. This fundamental knowledge serves throughout your electronics journey, from basic power distribution through sophisticated analog and digital systems. Master parallel circuits, and you have completed the foundation for understanding how components combine to create functional electronic systems.