Separating Fact from Fiction in Data Science

Every emerging field develops its mythology—a collection of beliefs, assumptions, and misconceptions that spread until they are accepted as truth despite being partially or completely wrong. Data science, which has exploded in popularity over the past decade, has accumulated its own extensive mythology. These myths shape how people perceive the field, influence career decisions, and create unrealistic expectations that lead to disappointment and frustration.

Some myths discourage talented people from entering data science because they believe they lack necessary qualifications they actually do not need. Other myths set people up for failure by creating false expectations about what the work involves or how quickly they can become proficient. Still others lead aspiring data scientists down inefficient learning paths, spending time on skills that matter less than they think while neglecting truly important competencies.

Understanding which commonly repeated statements about data science are myths versus reality helps you make better decisions about learning, career planning, and expectations. This article systematically examines ten of the most pervasive myths about data science, explains why they are wrong, and clarifies what the reality actually looks like. By the end, you will have a much more accurate picture of what data science requires and involves, enabling you to pursue it with appropriate expectations and strategies.

Myth 1: You Need a PhD to Become a Data Scientist

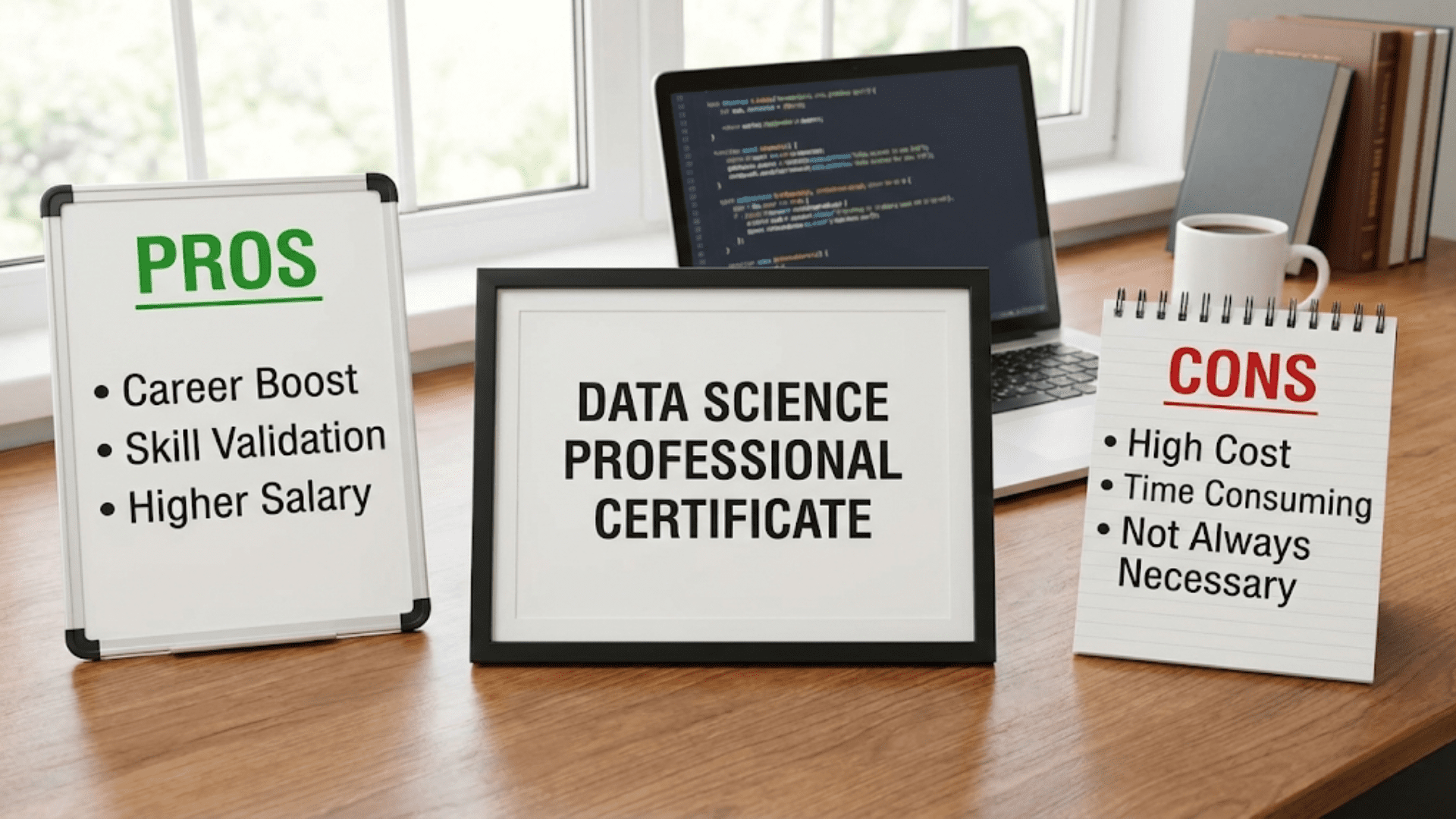

Perhaps no myth is more discouraging to potential data scientists than the belief that a doctoral degree in a quantitative field is required or even strongly preferred for data science careers. This myth persists because early data science roles were often filled by researchers with PhDs, and some companies still emphasize advanced degrees in job postings. However, the reality is far more accessible.

The truth is that many successful data scientists have bachelor’s degrees, and a significant number are self-taught or bootcamp-trained without traditional degrees at all. While PhDs can provide advantages—deep expertise in specific areas, research experience, and credibility in academic or research-heavy organizations—they are neither necessary nor sufficient for data science success. Practical skills, project experience, and the ability to solve real problems matter more than credentials.

The data science job market has matured considerably since its early days. Companies now recognize that many excellent data scientists come from diverse educational backgrounds. Career switchers from software engineering, business analysis, finance, and even non-technical fields successfully transition into data science roles without pursuing graduate degrees. What employers actually care about is demonstrated ability to work with data, extract insights, and communicate findings—capabilities you can develop through self-study, online courses, bootcamps, or undergraduate programs.

PhDs actually have disadvantages in some contexts. Doctoral training emphasizes theoretical depth and academic rigor, while industry data science prioritizes practical problem-solving, quick iteration, and business impact. PhD holders sometimes struggle with the faster pace and messier reality of industry work after years in academic environments. They may also face overqualification concerns or salary expectation mismatches, particularly for entry-level positions.

The relevant question is not whether you have a PhD but whether you have the right skills. Can you code in Python or R? Can you manipulate data with pandas? Do you understand statistics well enough to apply methods appropriately? Can you build machine learning models? Have you completed projects demonstrating these abilities? These questions determine your readiness for data science work far more than your degree level.

If you already have or are pursuing a PhD in a relevant field, it can certainly help your data science career. But if you are wondering whether to spend four to seven years earning a doctorate before starting in data science, the answer for most people is no. You can enter the field much faster through other paths, gain practical experience, and decide later whether advanced education would benefit your specific goals.

Myth 2: Data Scientists Spend Most of Their Time Building Models

Popular media and introductory courses create an impression that data scientists primarily develop sophisticated machine learning models, training neural networks, optimizing algorithms, and pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence. While model building does occur in data science work, it typically represents a small fraction of the actual time spent on projects.

The reality, repeatedly confirmed by surveys and practitioner reports, is that data scientists spend sixty to eighty percent of their time on data collection, cleaning, and preparation. This unglamorous work involves finding and accessing relevant data sources, combining data from multiple systems, handling missing values, correcting errors, standardizing formats, resolving inconsistencies, and transforming data into forms suitable for analysis. Only after this extensive preparation can model building begin.

Even when you reach the modeling phase, much of the work involves trying simple approaches first, evaluating whether more complex models are needed, debugging why models are not working, and iterating to improve performance. The exciting cutting-edge deep learning models you read about represent a tiny fraction of production data science work. Most projects use relatively simple techniques like linear regression, decision trees, or basic classification algorithms because they solve the problem adequately and are easier to maintain.

Beyond data preparation and modeling, data scientists spend substantial time on communication and collaboration. Meetings with stakeholders to understand business problems and requirements, discussions with engineering teams about implementation, presentations explaining findings to non-technical audiences, and documentation of analysis for future reference all consume significant time. The stereotype of the lone data scientist working in isolation building models rarely matches reality.

This reality is not a failure of the field but rather reflects what actual problem-solving looks like. Clean, well-organized data does not exist in nature—it must be created through careful work. Understanding business context requires conversation and iteration with stakeholders. Effective models must be explained to gain trust and drive decisions. All these activities are real data science work even though they lack the glamour of model building.

Understanding this reality helps you set appropriate expectations. If you love exclusively the algorithmic and mathematical aspects of machine learning, you might prefer a research role to a typical data science position. If you can appreciate the satisfaction of turning messy data into clean datasets, finding and fixing data quality issues, and helping people make better decisions, you will find data science work rewarding despite the limited time spent on what courses emphasize.

Myth 3: You Must Be a Math Genius to Do Data Science

Mathematics anxiety prevents many people from pursuing data science even when they might excel at it. The myth that data science requires advanced mathematical talent approaching genius level creates an unnecessary barrier. While mathematical competence is indeed required, the level needed for most data science work is far more accessible than this myth suggests.

The mathematical foundation for data science includes statistics, linear algebra, and calculus. Within statistics, you need understanding of probability, distributions, hypothesis testing, regression, and basic inference concepts. Linear algebra requires familiarity with vectors, matrices, and basic operations. Calculus concepts help you understand optimization and how algorithms learn. This sounds extensive, but the required depth is not as extreme as the myth implies.

For most data science applications, you need conceptual understanding more than computational mastery. You should understand what a derivative represents and why it matters for gradient descent, but you rarely calculate derivatives by hand. You should know what eigenvalues tell you about matrices and why they matter for dimensionality reduction, but you seldom compute eigenvalues manually. Libraries handle calculations while you focus on applying concepts appropriately.

Compare this to engineering or physics, which require solving complex mathematical problems regularly. Data scientists use mathematical concepts constantly but usually through software that handles the computational heavy lifting. Understanding when to use different statistical tests matters more than deriving the tests from first principles. Knowing which machine learning algorithms suit different problem types matters more than proving convergence theorems.

Many successful data scientists admit that they learned mathematics on a need-to-know basis while doing data science rather than mastering it completely beforehand. When you encounter a concept you do not understand, you study it enough to use it appropriately in your current project. This practical, application-driven approach to mathematical learning works well because you immediately apply new concepts, cementing understanding through use.

Strong mathematical intuition helps you become an excellent data scientist, but you can become a competent, employed data scientist with solid but not exceptional mathematical abilities. If you struggled with mathematics in school but are willing to learn statistical and mathematical concepts as needed for data analysis, do not let math anxiety stop you from pursuing data science.

The people who genuinely need deep mathematical expertise are those developing new algorithms, proving theoretical properties, or working on cutting-edge research problems. These specialized roles exist, but they represent a small fraction of data science positions. Most data science work uses existing, well-understood methods appropriately rather than inventing new mathematics.

Myth 4: Data Science Is Just Statistics with a New Name

From one direction, people claim data science is just rebranded statistics. From another, people insist data science has nothing to do with statistics at all. Both extremes miss the truth, which is that data science and statistics overlap substantially while remaining distinct in important ways.

Statistics provides foundational concepts, methods, and theory that underlie much of data science. Probability distributions, hypothesis testing, confidence intervals, regression analysis, experimental design, and inference all come from statistics. Data scientists use these tools constantly, and strong statistical knowledge makes you a better data scientist. In this sense, the claim that data science is applied statistics has merit.

However, data science extends beyond traditional statistics in several ways. The scale of data has changed dramatically, with modern datasets often containing millions or billions of observations that require computational approaches beyond traditional statistical methods. Data types have expanded to include text, images, video, network data, and other unstructured formats that classical statistics rarely addressed. Machine learning algorithms enable prediction and classification at scales and complexities that traditional statistical methods cannot match.

The tools and implementation methods differ significantly. Traditional statisticians might work in SAS, SPSS, or R with emphasis on careful study design and rigorous inference. Data scientists typically code in Python, work with messy observational data, and emphasize prediction and automation over inference and explanation. The mindset shifts from carefully designed studies with formal inference to rapid iteration, experimentation, and scalable systems.

Data science also draws heavily from computer science, incorporating databases, data structures, algorithms, software engineering practices, and distributed computing. These computational aspects fall outside traditional statistics curricula but are essential for modern data work. A statistician and a data scientist might both build regression models, but the data scientist may need to implement that model in a production system serving millions of requests per day—a concern beyond statistical theory.

The relationship is better described as data science incorporating statistics as one essential component alongside computer science, domain expertise, and communication skills. Data science is interdisciplinary in ways that statistics traditionally was not. This distinction matters because it clarifies what skills you need to develop. Statistical knowledge alone does not make you a data scientist, but neither does coding ability alone. The combination is what defines the field.

Traditional statisticians transitioning to data science need to learn programming, databases, and machine learning tools. Software engineers transitioning to data science need to learn statistics, experimental design, and inference. Both starting points can lead to success, but both require learning beyond their original discipline.

Myth 5: More Data Always Leads to Better Results

“Big data” hype has created a pervasive myth that having more data automatically produces better analysis and more accurate models. While data quantity certainly matters, this myth oversimplifies the relationship between data volume and quality of insights. More data can help tremendously, but it can also hurt if the data is wrong, irrelevant, or poorly used.

Quality matters more than quantity. A small dataset with accurate measurements, relevant variables, and representative sampling often yields better insights than a massive dataset with measurement errors, missing key variables, or systematic biases. Adding more bad data just gives you more bad data—it does not transform into good insights through sheer volume. Garbage in, garbage out remains true regardless of data size.

Relevance matters more than volume. Having millions of data points about the wrong things provides no value. If you are trying to predict customer churn but your data lacks information about customer satisfaction, product usage patterns, or support interactions, additional data about shipping addresses and payment methods will not help much. The right variables measured on fewer observations often beat wrong variables measured on more observations.

Diminishing returns apply to data quantity. Initial data points provide enormous value, but each additional observation contributes less. The difference between 100 and 1,000 observations is huge. The difference between 100,000 and 101,000 is negligible for most purposes. Beyond certain thresholds, adding more data improves models only marginally while increasing computational costs substantially.

More data can actually worsen results in some situations. Larger datasets take longer to process, requiring more computational resources and time. They may exceed memory capacity, forcing you to use sampling or specialized tools. Statistical significance becomes easier to achieve with more data, sometimes leading to findings that are statistically significant but practically meaningless. Models can overfit when data volume allows learning irrelevant patterns.

The myth also ignores the cost of acquiring, storing, and processing data. Each additional data point costs something in terms of collection time, storage space, processing power, and analysis effort. These costs must be justified by the value gained. Sometimes a carefully designed study with modest sample size provides better return on investment than attempting to collect massive datasets.

Smart data beats big data. Thoughtfully selected variables measured on well-chosen samples often outperform comprehensive data collection. Experimental data where you control variables usually beats observational data even when the observational dataset is much larger. Clean, validated data beats hastily collected data regardless of volume.

This does not mean data quantity is unimportant. More data does help in many situations, particularly for machine learning models that learn complex patterns. But data quality, relevance, representativeness, and appropriate analysis methods matter more than sheer volume. The goal should be getting the right data, not the most data.

Myth 6: Data Scientists Work Alone

Media portrayals often show data scientists as solitary figures hunched over computers, working in isolation to extract insights from data through individual brilliance. This lone genius myth misrepresents modern data science work, which is actually highly collaborative across multiple roles and departments.

Real data science projects involve extensive collaboration with stakeholders who define problems and requirements, provide domain expertise, and ultimately use the insights. Understanding business context requires conversation. Clarifying what questions actually need answering involves iteration with people who know the domain. Validating that findings make practical sense requires expert judgment. This stakeholder collaboration consumes significant time and is essential for impactful work.

Technical collaboration with other team members is equally important. Data engineers provide the infrastructure and pipelines that make data accessible. Software engineers integrate models into production systems. Other data scientists review your work, suggest improvements, and collaborate on large projects. Analysts provide context about existing metrics and reports. This teamwork is normal and necessary, not a sign of weakness.

Cross-functional projects are common, bringing together data scientists with product managers, designers, marketers, operations staff, and executives. A recommendation system project might involve data scientists building models, engineers implementing them, designers creating interfaces, product managers defining requirements, and executives making strategic decisions. Success requires coordination across all these functions.

Communication skills matter as much as technical skills precisely because collaboration is central. Explaining technical concepts to non-technical audiences, documenting work for others to understand, presenting findings clearly, and negotiating priorities across teams are all critical data science activities. The stereotype of the socially awkward but brilliant data scientist working alone is both inaccurate and unhelpful.

Even in organizations with solo data scientists—common in smaller companies—the role still involves constant interaction with other departments. You might be the only data person, but you still collaborate with everyone who has questions about data or needs analysis to inform decisions. Being solo makes collaboration even more important since you cannot rely on other data scientists for support.

Remote work has increased in data science like other fields, but remote does not mean isolated. Virtual collaboration through video calls, shared documents, messaging platforms, and code repositories enables teamwork even when people are not physically together. The collaboration style may differ, but the need remains.

If you are attracted to data science because you want to work alone without dealing with people, you may be disappointed. If you enjoy teamwork, bringing diverse perspectives together, and seeing your work drive real decisions through collaboration, you will find data science rewarding.

Myth 7: You Need to Learn Everything Before Getting Started

The sheer breadth of data science creates paralysis in many beginners who believe they must master Python, R, SQL, statistics, linear algebra, calculus, machine learning, deep learning, data visualization, databases, cloud platforms, and a dozen other topics before they can begin doing real data science work. This myth prevents people from starting and leads to endless preparation without practical experience.

The reality is that data science practitioners learn continuously throughout their careers. Nobody knows everything, and the field evolves too rapidly for complete knowledge to be possible. Successful data scientists develop specific skills for their current needs and learn additional topics as projects require them. This just-in-time learning approach is not just acceptable but actually more effective than attempting to learn everything upfront.

You can begin doing data science with surprisingly modest skills. Basic Python programming, fundamental pandas operations, simple statistics, and basic visualization enable you to load data, explore it, calculate summary statistics, create charts, and draw preliminary conclusions. These core skills let you complete small projects and start building experience. As you encounter new challenges, you learn the specific techniques needed to address them.

Starting with limited skills and learning through projects provides context that makes new concepts stick better. When you learn hypothesis testing because you need to determine if observed differences are statistically significant in your current project, the motivation is clear and the application immediate. This differs dramatically from learning hypothesis testing abstractly before knowing why you would use it.

The breadth of data science means different roles emphasize different skills. Analytics-focused roles need strong SQL and statistics but less machine learning. Machine learning roles need algorithms and programming but less emphasis on statistical inference. Understanding your target role helps you prioritize what to learn rather than trying to master everything.

Many successful data scientists specialize in subdomains. Some focus on computer vision, others on natural language processing, some on time series forecasting, others on recommendation systems. Deep expertise in one area often proves more valuable than shallow knowledge across everything. You can become highly successful knowing one corner of data science well.

The “learn everything first” myth also ignores the reality that much learning happens on the job. Companies expect to provide some training and ramp-up time. Colleagues help you learn their specific tools and methods. Real projects teach you skills that no course covers. Hands-on experience accelerates learning faster than study alone.

The right approach is to learn core fundamentals, start building projects, and expand your knowledge progressively based on what you need and what interests you. Accept that you will always be learning, that gaps in your knowledge are normal, and that the journey of continuous learning is part of what makes data science engaging rather than a problem to solve before starting.

Myth 8: Data Science Is Only for Tech Companies

The prominence of technology companies in data science creates the impression that data science careers exist primarily or exclusively in the tech sector. While tech companies certainly employ many data scientists and often push the field forward, data science applications span virtually every industry.

Healthcare organizations use data science for disease diagnosis, treatment effectiveness analysis, patient readmission prediction, resource allocation optimization, and drug discovery. Financial services employ data scientists for fraud detection, credit risk assessment, algorithmic trading, customer segmentation, and regulatory compliance. Retail and e-commerce companies apply data science to demand forecasting, pricing optimization, inventory management, and recommendation systems.

Manufacturing uses data science for quality control, predictive maintenance, supply chain optimization, and process improvement. Energy companies apply it to consumption forecasting, grid optimization, and exploration. Transportation and logistics optimize routes, predict delays, and manage fleets. Government agencies use data science for policy analysis, resource allocation, fraud detection, and public health monitoring.

Entertainment companies use data science for content recommendations, audience analysis, and production decisions. Education applies it to personalized learning, student success prediction, and program evaluation. Agriculture uses it for crop yield prediction, precision farming, and resource optimization. Sports teams employ data scientists for player evaluation, strategy optimization, and injury prediction.

Essentially any organization that collects data—which means virtually all modern organizations—can benefit from data science. The specific applications and tools may vary across industries, but the fundamental skills transfer. Understanding business context and domain-specific knowledge becomes more important than technical differences between industries.

Non-tech industries sometimes offer advantages for data science careers. You may face less competition than in tech hubs where everyone wants to work for famous technology companies. Your work might have more visible real-world impact in healthcare, government, or social services than in advertising optimization. Compensation can be competitive, particularly in finance and consulting. Career growth may be faster if you are one of few data scientists rather than one of hundreds.

The belief that data science is only for tech companies limits your career options unnecessarily. If you have interest or background in healthcare, finance, manufacturing, or any other domain, combining that knowledge with data science skills makes you particularly valuable. Domain expertise helps you ask better questions, interpret findings correctly, and communicate with stakeholders effectively.

Geographic location matters less than this myth suggests as well. While Silicon Valley, Seattle, and New York have high concentrations of data science roles, opportunities exist in cities of all sizes and in many countries. Remote work has expanded options even further. You do not need to live in a tech hub to have a data science career.

Myth 9: Automating Machine Learning Will Eliminate Data Scientists

The rise of automated machine learning (AutoML) tools that automatically select algorithms, tune hyperparameters, and generate models has led some to predict that data scientists will soon be unnecessary. Tools like H2O AutoML, Google AutoML, and various automated feature engineering platforms can indeed build models with minimal human intervention. However, the prediction that these tools will eliminate data scientists reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what data scientists actually do.

AutoML tools are excellent at the algorithmic model building part of data science, which as discussed earlier, represents only a small fraction of the work. They cannot define the business problem worth solving, identify what data would be relevant, access and combine data from various sources, clean messy real-world data, engineer features based on domain knowledge, determine whether the model actually answers the business question, or explain findings to stakeholders in ways that drive decisions.

Even in the modeling phase where AutoML excels, human judgment remains critical. AutoML optimizes for metrics you specify, but choosing the right metrics requires understanding the business context and costs of different error types. AutoML provides a model, but you must evaluate whether it is interpretable enough for your needs, whether it will generalize to new data, whether it exhibits unwanted biases, and whether it can be deployed and maintained.

The historical pattern with automation in other fields provides context. When spreadsheets automated calculations that accountants previously did manually, the accounting profession did not disappear. Instead, accountants shifted to higher-value work requiring judgment and expertise. When legal research databases automated what junior lawyers once did manually, the legal profession adapted rather than vanishing. Automation typically eliminates the most routine tasks while creating demand for more sophisticated work.

AutoML tools actually make data scientists more productive by automating tedious parts of model development, allowing them to try more approaches faster and focus on higher-level problems. Good data scientists embrace these tools rather than fearing them. They become force multipliers that let you accomplish more rather than replacements for human expertise.

The skills that matter most for data scientists are precisely the ones automation cannot easily replicate: understanding business problems, communicating with stakeholders, applying domain knowledge, making judgment calls about tradeoffs, designing experiments, asking the right questions, and translating findings into actions. These human-centered skills become more important as tools handle more of the technical mechanics.

Rather than worrying about automation eliminating data science careers, focus on developing the skills that complement automation tools. Learn to frame business problems well, communicate effectively, understand domain contexts deeply, and make sound judgments. These capabilities combined with technical proficiency and comfort with automation tools position you for long-term success.

Myth 10: Data Science Is a Solo Career Path

The final myth positions data science as a single, linear career path where you become a data scientist and remain one throughout your career. This narrow view ignores the diverse career directions available to people with data science skills and the reality that many paths lead to and from data science roles.

Data science skills open doors to numerous adjacent roles. Many data scientists move into machine learning engineering, focusing on deploying and scaling models in production. Others transition to data engineering, building the infrastructure that makes data accessible. Some move into product management, using their analytical skills and technical understanding to guide product development. Analytics management positions lead teams and shape organizational analytics strategy.

Business roles benefit enormously from data science backgrounds. Data-literate business leaders make better decisions and can ask better questions of their analytics teams. Consultants with data science expertise command premium rates. Entrepreneurs with data skills can build data-driven products or services. These career moves leverage data science knowledge without requiring you to remain in hands-on technical roles.

Research positions in industry or academia provide paths for those interested in pushing the field forward rather than applying existing methods. Teaching and training roles help others develop data science skills. Technical writing and communication roles translate complex topics for various audiences. The skills developed through data science transfer broadly.

Many people come to data science from other careers and may leave for other opportunities. A software engineer might spend several years in data science then return to engineering with new perspectives. A domain expert might learn data science to analyze problems in their field then move back to domain work with analytical superpowers. These lateral moves are common and valuable.

Within data science itself, specialization creates different paths. Some people focus on deep learning and computer vision. Others specialize in natural language processing. Some become experts in time series and forecasting. Others focus on experimentation and causal inference. These specializations require different skills and appeal to different interests.

Career progression in data science does not look the same for everyone. Some people pursue management track positions, leading teams and shaping strategy. Others prefer individual contributor tracks, becoming senior or principal data scientists with deep technical expertise. Both paths are legitimate and valuable. Your career choices should reflect your interests and strengths rather than following a prescribed path.

The myth of a single career path creates unnecessary anxiety about whether data science is “right” for you as a permanent career. The reality is that data science skills provide options and flexibility. You can stay in data science long-term if you love it, or use it as a foundation for other directions if your interests change. The analytical thinking, technical skills, and problem-solving approaches you develop transfer across many roles and industries.

Conclusion

These ten myths—requiring PhDs, spending all time on models, needing mathematical genius, just being statistics, more data always helping, working alone, needing to know everything before starting, only for tech companies, being eliminated by automation, and following a single career path—persist because they contain kernels of truth stretched into oversimplifications. PhDs can help but are not required. Model building happens but is not the majority of work. Mathematics matters but genius is not needed. Data science uses statistics but extends beyond it.

Understanding the reality behind these myths helps you make better decisions about pursuing data science, learning effectively, setting appropriate expectations, and planning your career. The field is more accessible than some myths suggest and more complex than others imply. Success comes not from fitting a mythical profile but from developing practical skills, gaining experience, communicating effectively, and continuously learning.

Data science offers rewarding careers for people with diverse backgrounds, interests, and goals. Do not let myths discourage you from exploring the field if it interests you. Do not let myths create unrealistic expectations that set you up for disappointment. Approach data science with clear understanding of what it actually involves, and you will be better positioned to thrive in this dynamic and impactful field.

In the next article, we will explore whether you need a PhD to become a data scientist in greater depth, examining the specific situations where advanced degrees help, alternative paths to data science careers, and how to evaluate whether pursuing graduate education makes sense for your particular circumstances and goals.

Key Takeaways

PhD degrees can help data science careers but are neither necessary nor sufficient for success, with many excellent data scientists coming from diverse educational backgrounds including bachelor’s degrees, bootcamps, and self-teaching. The emphasis on PhDs in early data science created a myth that persists despite the field maturing to value practical skills and demonstrated ability over credentials alone.

Data scientists spend sixty to eighty percent of their time on data collection, cleaning, and preparation rather than building models, with additional time devoted to communication, stakeholder collaboration, and business understanding. The glamorous model-building work represents a small fraction of actual data science activities, and understanding this reality helps set appropriate expectations.

Mathematical competence is required for data science but not mathematical genius, with conceptual understanding of statistics, linear algebra, and calculus being more important than computational mastery or advanced theoretical knowledge. Most data science work uses existing mathematical methods appropriately through libraries rather than developing new mathematics or performing complex calculations manually.

Data science and statistics overlap substantially while remaining distinct fields, with data science incorporating statistics alongside computer science, domain expertise, and communication skills in ways that traditional statistics did not emphasize. Understanding this interdisciplinary nature clarifies what skills you need to develop beyond statistical knowledge alone.

Data quality, relevance, and representativeness matter more than sheer volume, with small high-quality datasets often yielding better insights than massive low-quality ones, and diminishing returns applying beyond certain data size thresholds. The myth that more data always improves results ignores the costs of data collection, processing challenges with large datasets, and the reality that wrong or irrelevant data provides no value regardless of quantity.

Data science work is highly collaborative rather than solitary, involving extensive interaction with stakeholders, technical team members, and cross-functional partners throughout all project phases. Communication and teamwork skills are as important as technical abilities precisely because collaboration is central to data science success in organizations.