The Spreadsheet That Changed Data Science

Imagine trying to organize information about hundreds of customers, each with a name, age, location, purchase history, and dozens of other attributes. You could write it all on paper in neat columns, but updating would be tedious and error-prone. You could use separate lists in your code, but keeping everything synchronized would be a nightmare. You need something better—a structure that organizes information naturally, allows easy access and modification, and supports the analytical operations you need to perform. This is exactly what a DataFrame provides.

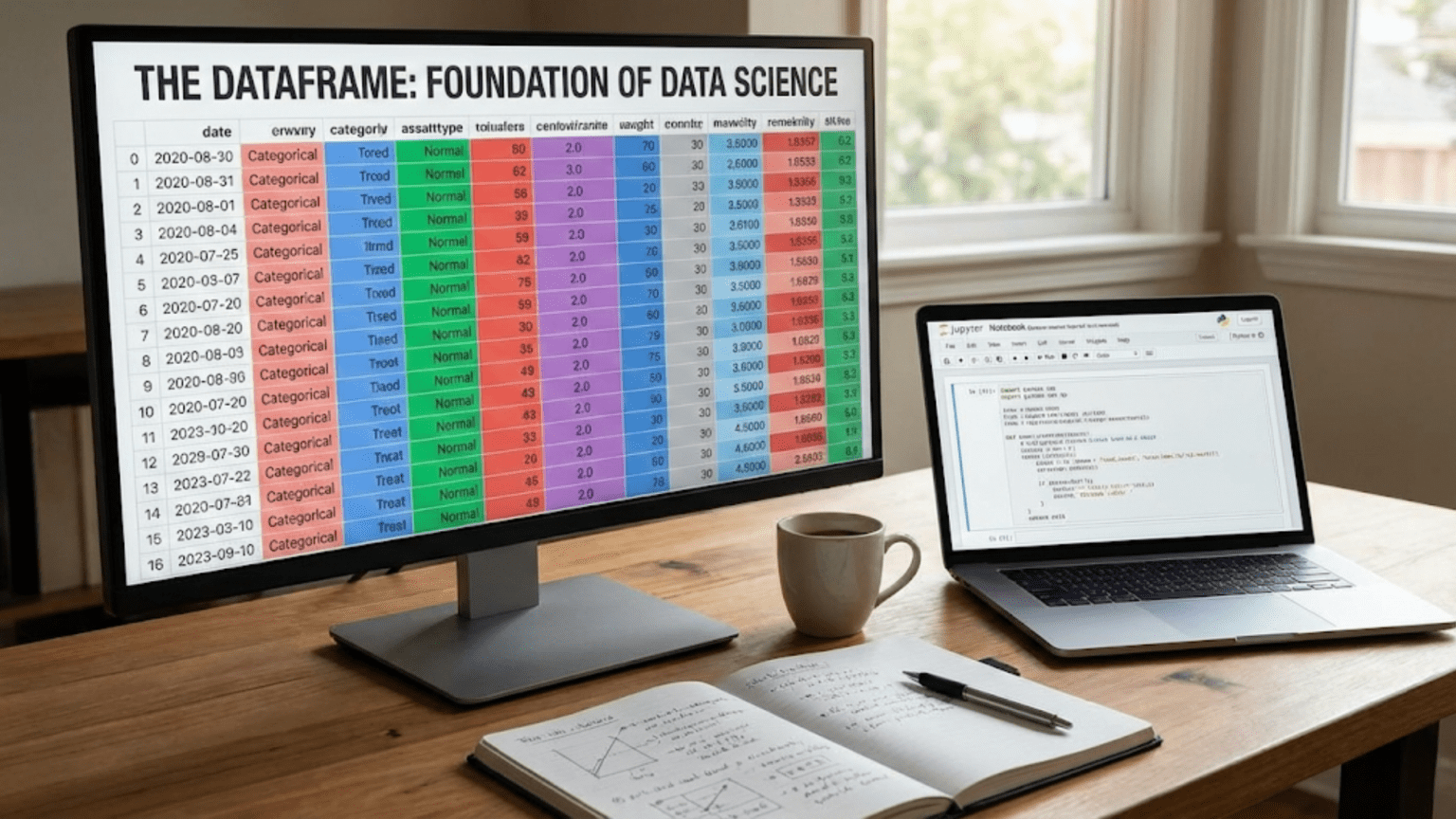

The DataFrame has become the fundamental data structure in modern data science, so ubiquitous that you will work with DataFrames in virtually every data project you undertake. If data science were construction, DataFrames would be the foundation on which everything else is built. Understanding DataFrames deeply—what they are, how they work, and how to manipulate them—is not optional knowledge but essential competency that separates people who can actually do data science from those who only understand it theoretically.

Yet many beginners struggle to develop a clear mental model of DataFrames. They see code examples and can follow along, but do not truly understand what is happening beneath the surface. This article builds that mental model from the ground up, explaining DataFrames in clear, concrete terms with practical examples. By the end, you will not just know what a DataFrame is, but understand it so thoroughly that working with data feels natural and intuitive rather than mysterious and frustrating.

DataFrames: Spreadsheets with Superpowers

The simplest way to understand a DataFrame is to think of it as a supercharged spreadsheet. If you have ever used Excel or Google Sheets, you already understand the basic concept. DataFrames organize data into rows and columns, just like spreadsheets. Each row represents a single record or observation, and each column represents a specific attribute or variable that you measured or collected.

Consider a simple example: information about students in a class. Each row represents one student, and columns contain attributes like name, age, grade, and attendance. This tabular structure feels natural because it matches how we intuitively organize information. Your brain does not have to work hard to understand what a row of student data represents or what the columns mean.

However, DataFrames go far beyond simple spreadsheets in critical ways. While spreadsheets are primarily designed for human interaction with data through a graphical interface, DataFrames are designed for programmatic manipulation through code. This difference is profound. In Excel, you might manually sort a column, filter rows by clicking buttons, or calculate a sum by dragging a formula. With DataFrames, you write code that performs these operations automatically, reproducibly, and at scale.

DataFrames in Python, specifically pandas DataFrames which have become the standard, provide hundreds of built-in methods for data manipulation that would be tedious or impossible in spreadsheets. You can filter millions of rows based on complex conditions instantly, join multiple datasets together seamlessly, handle missing data systematically, reshape data from wide to long format or vice versa, and perform sophisticated aggregations grouped by multiple variables—all with just a few lines of code.

The DataFrame structure also enforces consistency that spreadsheets lack. Each column in a DataFrame has a defined data type—integers, floats, strings, dates, or categories. This type enforcement prevents many errors that plague spreadsheet analysis, where accidentally mixing numbers and text in a column causes calculations to fail mysteriously. DataFrames validate that operations make sense for the data types involved, catching mistakes before they propagate through your analysis.

Perhaps most importantly, DataFrames integrate seamlessly with the entire Python data science ecosystem. Machine learning libraries expect DataFrames as input. Visualization tools work natively with DataFrames. Statistical packages operate on DataFrames. This interoperability means you can move smoothly from loading data to cleaning it to analyzing it to modeling it to visualizing results, all while working with the same DataFrame structure.

The Anatomy of a DataFrame: Labels, Indices, and Values

To truly understand DataFrames, you need to grasp their internal structure. DataFrames consist of three essential components: the index, the columns, and the underlying data values. Each component plays a specific role in organizing and accessing information.

The index provides labels for rows. Think of it as the row numbers in a spreadsheet, except indices can be numbers, text labels, dates, or any other type that uniquely identifies rows. By default, pandas creates a numeric index starting at 0, so the first row has index 0, the second has index 1, and so on. However, you can set any column as the index, making it easier to look up specific records.

For example, in a student DataFrame, you might set student IDs as the index. Then you could access a specific student’s information using their ID rather than needing to know their position in the table. Indices make DataFrames fundamentally more powerful than simple two-dimensional arrays because they provide meaningful labels for accessing data rather than just positional numbers.

Column names label the attributes in your DataFrame. Each column has a name that describes what information it contains. These names are not just documentation—they are how you access and manipulate specific variables in your data. Good column names are descriptive, concise, and follow consistent naming conventions. Names like “customer_age” and “purchase_date” immediately communicate what the columns contain, while names like “col1” and “x” provide no useful information.

The data values form the actual content of your DataFrame, organized in a two-dimensional grid where each cell contains a value for a specific observation and variable. Under the hood, pandas stores these values efficiently in NumPy arrays, enabling fast numerical operations. The key insight is that while DataFrames appear as tables, they are actually collections of one-dimensional arrays (Series) aligned by a common index.

Each column in a DataFrame is actually a pandas Series—a one-dimensional labeled array. A DataFrame is essentially a collection of Series that share the same index. This relationship explains many DataFrame behaviors. Operations on columns feel similar to operations on arrays because columns are arrays with labels. When you select a single column from a DataFrame, you get a Series. When you combine multiple Series with the same index, you get a DataFrame.

The relationship between DataFrames and Series is like the relationship between tables and columns. Just as a table consists of multiple columns, a DataFrame consists of multiple Series. Understanding this hierarchy helps you predict how operations will behave and moves you from following examples mechanically to understanding the logic behind DataFrame operations.

Creating DataFrames: From Dictionaries to Files

Before you can work with DataFrames, you need to create them or load them from data sources. Understanding the various ways to create DataFrames helps you convert data from different formats into the DataFrame structure you need for analysis.

The most basic way to create a DataFrame is from a Python dictionary where keys become column names and values become column data:

import pandas as pd

data = {

'name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'David'],

'age': [25, 30, 35, 28],

'city': ['New York', 'Los Angeles', 'Chicago', 'Houston']

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print(df)This creates a DataFrame with three columns (name, age, city) and four rows. The dictionary syntax is intuitive—each key-value pair defines one column and its values. This approach works well for small datasets you create manually or when converting existing Python data structures to DataFrames.

You can also create DataFrames from lists of lists, where each inner list represents a row:

data = [

['Alice', 25, 'New York'],

['Bob', 30, 'Los Angeles'],

['Charlie', 35, 'Chicago'],

['David', 28, 'Houston']

]

df = pd.DataFrame(data, columns=['name', 'age', 'city'])

print(df)When creating from lists of lists, you must specify column names separately since the data structure itself does not include them. This format mirrors how you might think about tabular data row-by-row.

In practice, you rarely create DataFrames manually. Instead, you load data from files that contain datasets you want to analyze. The most common file format is CSV (comma-separated values):

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv')This single line reads a CSV file and converts it to a DataFrame, automatically detecting column names from the first row and inferring data types for each column. Pandas makes this incredibly simple—no need to manually parse files, split strings, or convert types.

Pandas can read numerous other formats:

# Excel files

df = pd.read_excel('data.xlsx', sheet_name='Sheet1')

# JSON files

df = pd.read_json('data.json')

# SQL databases

import sqlite3

conn = sqlite3.connect('database.db')

df = pd.read_sql_query('SELECT * FROM table_name', conn)

# Direct from URLs

df = pd.read_csv('https://example.com/data.csv')This flexibility means you can work with data regardless of how it is stored. The DataFrame structure standardizes data access across all these different sources, letting you focus on analysis rather than file format complications.

When loading data, you often need to specify additional parameters to handle real-world file quirks:

df = pd.read_csv('data.csv',

sep=';', # Different separator

encoding='utf-8', # Character encoding

na_values=['NA', ''], # What counts as missing

parse_dates=['date'], # Convert to datetime

index_col='id') # Set index columnUnderstanding these parameters helps you handle messy real-world data that does not conform to ideal formats.

Examining DataFrames: Your First Look at Data

Once you have a DataFrame, your first task is understanding what it contains. Pandas provides numerous methods for examining DataFrames that become part of your standard workflow when approaching any new dataset.

The head() method shows the first few rows:

df = pd.read_csv('sales_data.csv')

print(df.head()) # Default shows 5 rows

print(df.head(10)) # Show 10 rowsThis quick peek helps you understand the data structure, see actual values, and verify the data loaded correctly. Similarly, tail() shows the last few rows, useful for checking if data loaded completely.

The info() method provides a comprehensive summary:

print(df.info())This displays the number of rows and columns, lists all column names with their data types, shows how many non-null values each column contains, and reports memory usage. This information is invaluable for getting oriented with a new dataset. Missing values become immediately apparent, and data type issues reveal themselves.

The describe() method generates statistical summaries for numerical columns:

print(df.describe())You see count, mean, standard deviation, minimum, quartiles, and maximum for each numeric column. These statistics provide quick insight into data distributions, ranges, and potential outliers. For non-numeric columns, describe() with the include='all' parameter shows counts, unique values, and most frequent values.

The shape attribute tells you dimensions:

print(df.shape) # Returns (rows, columns)Knowing you have 10,000 rows and 15 columns immediately helps you understand the dataset’s size and scope.

Column names and data types are accessible:

print(df.columns) # All column names

print(df.dtypes) # Data type of each columnThese help you understand what information is available and how pandas is interpreting each column. Type mismatches often cause analysis problems, so checking types early prevents frustration later.

Sample rows give you a broader view than just the first few:

print(df.sample(10)) # 10 random rowsRandom sampling reveals different aspects of your data than just looking at the beginning or end, helping you spot patterns or issues that do not appear in the first rows.

These exploratory methods become automatic. When you load any new DataFrame, you immediately run head(), info(), and describe() to understand what you are working with. This habit prevents surprises and helps you plan your analysis approach.

Accessing Data: Selecting Rows and Columns

DataFrames would be useless if you could not easily access the specific data you need. Pandas provides multiple ways to select and filter data, each suited to different situations.

Selecting columns by name is the most basic operation:

# Single column returns a Series

ages = df['age']

print(type(ages)) # pandas.core.series.Series

# Multiple columns returns a DataFrame

subset = df[['name', 'age']]

print(type(subset)) # pandas.core.frame.DataFrameNote the double brackets when selecting multiple columns—the inner list contains column names, and the outer brackets perform the selection operation. This syntax takes some getting used to but becomes natural with practice.

Filtering rows based on conditions is fundamental to data analysis:

# Simple condition

young = df[df['age'] < 30]

# Multiple conditions with &(and) and |(or)

young_in_ny = df[(df['age'] < 30) & (df['city'] == 'New York')]

ny_or_la = df[(df['city'] == 'New York') | (df['city'] == 'Los Angeles')]

# Using isin for multiple values

big_cities = df[df['city'].isin(['New York', 'Los Angeles', 'Chicago'])]Boolean indexing like this is powerful—you create a boolean Series indicating which rows meet your criteria, then use it to filter the DataFrame. The expressions inside brackets evaluate to True or False for each row, and only True rows are kept.

The loc and iloc methods provide more explicit ways to access data:

# loc uses labels (row and column names)

df.loc[0, 'name'] # Single value

df.loc[0:5, ['name', 'age']] # Range of rows, specific columns

df.loc[df['age'] > 30, 'city'] # Conditional rows, single column

# iloc uses integer positions (like array indexing)

df.iloc[0, 0] # First row, first column

df.iloc[0:5, 0:3] # First 5 rows, first 3 columns

df.iloc[:, 0] # All rows, first columnThe distinction between loc (label-based) and iloc (position-based) is important. Use loc when you know names, iloc when you know positions. The loc method is generally preferred because it is more explicit and less prone to errors when data order changes.

Selecting specific rows by index value:

# If you have set meaningful indices

df_indexed = df.set_index('name')

print(df_indexed.loc['Alice']) # Get Alice's rowThis is powerful when you have natural identifiers like student IDs, product codes, or customer numbers that should serve as indices.

Modifying DataFrames: Adding, Changing, and Removing Data

Data rarely arrives in exactly the form you need. DataFrames must be modified—adding new columns, updating values, removing unnecessary data—to prepare for analysis.

Adding new columns is straightforward:

# Add column with constant value

df['country'] = 'USA'

# Add column calculated from existing columns

df['age_next_year'] = df['age'] + 1

# Add column based on conditions

df['age_group'] = df['age'].apply(lambda x: 'young' if x < 30 else 'older')New columns can be constants, calculations, or conditional transformations. The ability to create derived columns from existing data is fundamental to feature engineering in machine learning.

Modifying existing values uses similar syntax:

# Update all values in a column

df['age'] = df['age'] + 1

# Update specific values

df.loc[df['name'] == 'Alice', 'age'] = 26

# Update multiple columns

df.loc[df['age'] < 30, ['age_group', 'status']] = ['young', 'active']The loc method is preferred for updates because it explicitly shows what you are modifying and avoids potential warnings about modifying copies versus views.

Renaming columns improves clarity:

# Rename specific columns

df = df.rename(columns={'old_name': 'new_name', 'age': 'customer_age'})

# Rename all columns with a function

df.columns = df.columns.str.lower() # Lowercase all column namesConsistent naming conventions make code more readable and prevent errors from typos in column names.

Dropping columns removes unnecessary data:

# Drop single column

df = df.drop('unnecessary_column', axis=1)

# Drop multiple columns

df = df.drop(['col1', 'col2', 'col3'], axis=1)

# Alternative: keep only specific columns

df = df[['name', 'age', 'city']]The axis=1 parameter specifies columns (axis=0 would be rows). Dropping columns reduces memory usage and simplifies analysis by removing distractions.

Dropping rows removes observations:

# Drop by index

df = df.drop([0, 1, 2])

# Drop rows with missing values

df = df.dropna()

# Drop duplicate rows

df = df.drop_duplicates()

# Drop based on conditions (just don't select them)

df = df[df['age'] >= 18] # Keep only adultsRemoving invalid, duplicate, or irrelevant rows cleans your dataset for analysis.

All these operations return new DataFrames by default, leaving the original unchanged unless you use the inplace=True parameter:

# Creates new DataFrame

df_new = df.drop('column', axis=1)

# Modifies original DataFrame

df.drop('column', axis=1, inplace=True)Many data scientists prefer the non-inplace approach because it is safer—you can always go back to the original if something goes wrong.

Sorting and Organizing DataFrames

The order of rows in a DataFrame affects readability and sometimes impacts analysis. Pandas provides flexible sorting capabilities that let you organize data meaningfully.

Sorting by single column:

# Ascending order (default)

df_sorted = df.sort_values('age')

# Descending order

df_sorted = df.sort_values('age', ascending=False)Sorting makes patterns more visible. Arranging customers by purchase amount from highest to lowest immediately highlights your most valuable customers.

Sorting by multiple columns:

# Sort by city, then by age within each city

df_sorted = df.sort_values(['city', 'age'])

# Different order for different columns

df_sorted = df.sort_values(['city', 'age'], ascending=[True, False])Multi-level sorting organizes data hierarchically, grouping related records together.

Sorting by index:

df_sorted = df.sort_index()This is useful when your index has meaningful order, like dates or sequential IDs that got scrambled during manipulation.

Resetting the index after filtering or sorting:

df = df.reset_index(drop=True)Filtering and sorting can create gaps in the numeric index. Resetting renumbers rows sequentially, which is often cleaner for subsequent operations.

Handling Missing Data in DataFrames

Real-world data invariably contains missing values. DataFrames provide systematic ways to detect and handle these gaps rather than letting them silently corrupt analysis.

Detecting missing values:

# Boolean DataFrame showing where values are missing

print(df.isnull())

# Count of missing values per column

print(df.isnull().sum())

# Rows with any missing values

print(df[df.isnull().any(axis=1)])These checks reveal the extent and location of missing data, informing how you handle it.

Removing missing data:

# Drop rows with any missing values

df_clean = df.dropna()

# Drop rows where specific columns are missing

df_clean = df.dropna(subset=['age', 'city'])

# Drop columns with any missing values

df_clean = df.dropna(axis=1)Dropping is simple but loses information. Use it when you have plenty of data and missing values are random.

Filling missing values:

# Fill with constant

df_filled = df.fillna(0)

# Fill with column mean

df['age'] = df['age'].fillna(df['age'].mean())

# Forward fill (use previous valid value)

df_filled = df.fillna(method='ffill')

# Fill with different values for different columns

df = df.fillna({'age': df['age'].median(), 'city': 'Unknown'})Imputation preserves data size but makes assumptions about missing values. The appropriate method depends on why values are missing and how they relate to other variables.

Grouping and Aggregating: The Power of Split-Apply-Combine

One of the most powerful DataFrame operations is grouping data by categories and calculating statistics for each group. This split-apply-combine pattern underlies much of data analysis.

Basic grouping and aggregation:

# Mean age by city

city_avg_age = df.groupby('city')['age'].mean()

# Multiple aggregations

city_stats = df.groupby('city')['age'].agg(['mean', 'min', 'max', 'count'])

# Aggregate multiple columns

city_summary = df.groupby('city').agg({

'age': 'mean',

'salary': ['mean', 'sum'],

'name': 'count'

})Grouping reveals patterns across categories. Comparing average purchase amounts by customer segment or failure rates by product type requires grouping.

Multiple grouping levels:

# Group by multiple columns

region_city_stats = df.groupby(['region', 'city'])['sales'].sum()This creates hierarchical groupings, useful for analyzing data at different levels of granularity.

The groupby operation conceptually splits the DataFrame into pieces based on grouping variables, applies a function to each piece, and combines results. Understanding this logic helps you leverage groupby for sophisticated analyses.

Merging and Joining DataFrames

Real projects involve data from multiple sources that must be combined. DataFrames provide powerful joining operations similar to SQL database joins.

Concatenating DataFrames vertically (stacking rows):

# Combine rows from multiple DataFrames

df_combined = pd.concat([df1, df2, df3])

# Reset index after concatenation

df_combined = pd.concat([df1, df2], ignore_index=True)This is useful when you have the same columns in multiple files, like monthly data files you want to combine into yearly data.

Joining DataFrames horizontally (matching rows):

# Inner join (only matching rows)

df_merged = pd.merge(df1, df2, on='customer_id', how='inner')

# Left join (all rows from df1)

df_merged = pd.merge(df1, df2, on='customer_id', how='left')

# Join on multiple columns

df_merged = pd.merge(df1, df2, on=['date', 'store'], how='inner')

# Join on different column names

df_merged = pd.merge(df1, df2, left_on='cust_id', right_on='customer_id')These operations are essential for combining related datasets, like joining customer information with purchase history or product details with inventory data.

Why DataFrames Matter for Your Data Science Journey

DataFrames are not just another data structure to learn—they are the foundation that everything else in data science builds upon. Every tutorial you follow, every course you take, and every project you work on will involve DataFrames. Time invested in truly understanding them pays dividends immediately and continuously throughout your career.

When you master DataFrames, loading data becomes trivial, cleaning data becomes manageable, exploratory analysis becomes natural, and preparation for modeling becomes straightforward. You can focus your mental energy on understanding your data and extracting insights rather than fighting with technical details of data manipulation.

The operations covered in this article—selecting, filtering, adding columns, grouping, joining—are not isolated techniques but building blocks you combine to solve real problems. A typical analysis might filter rows based on dates, create new calculated columns, group by categories, aggregate statistics, join with another dataset, and finally export results. Each step uses the DataFrame operations you have learned.

Conclusion

DataFrames organize data into labeled rows and columns, providing intuitive structure with powerful programmatic manipulation capabilities that go far beyond spreadsheets. Understanding DataFrames’ anatomy—indices, columns, and values—helps you predict how operations will behave and move from mechanically following examples to understanding the logic behind data manipulation.

Creating DataFrames from dictionaries, lists, or files is straightforward with pandas, and examining them with methods like head(), info(), and describe() should become your automatic first step with any new dataset. Accessing specific rows and columns through various selection methods, filtering with boolean conditions, and using loc and iloc for explicit access gives you precise control over your data.

Modifying DataFrames by adding columns, changing values, and removing unnecessary data prepares datasets for analysis, while handling missing values systematically prevents data quality issues from corrupting results. Grouping and aggregating with the split-apply-combine pattern, along with merging and joining operations, enable sophisticated analyses combining multiple data sources.

DataFrames are the foundation of data science in Python, and mastering them is not optional but essential for effective analysis. The time you invest in understanding DataFrames deeply makes every subsequent step in your data science journey easier and more productive.

In the next article, we will dive into reading your first CSV file with Python pandas, walking through the complete process from file to DataFrame to initial analysis. This practical application will solidify your DataFrame understanding with real hands-on experience.

Key Takeaways

DataFrames are the fundamental data structure in data science, organizing information into labeled rows and columns like supercharged spreadsheets designed for programmatic manipulation rather than manual interaction. Each DataFrame consists of three components: an index labeling rows, column names labeling attributes, and the underlying data values stored efficiently in NumPy arrays.

Creating DataFrames from Python dictionaries, lists, or files is straightforward with pandas, with pd.read_csv() being the most common method for loading real-world data from CSV files. Examining DataFrames immediately after loading using head(), info(), describe(), and related methods should become automatic habit for understanding structure, data types, and potential issues.

Accessing data in DataFrames uses multiple approaches including column selection by name, boolean filtering for conditional row selection, and explicit loc and iloc methods for label-based and position-based access respectively. Modifying DataFrames through adding columns, updating values, and removing rows or columns prepares data for analysis, with operations typically returning new DataFrames unless inplace=True is specified.

Handling missing data systematically with isnull(), dropna(), and fillna() prevents data quality issues from corrupting analysis, while grouping with groupby() implements the powerful split-apply-combine pattern for category-wise aggregation. Merging and joining operations combine data from multiple sources, enabling sophisticated analyses that draw on information across datasets.

Mastering DataFrames is essential rather than optional for data science, as they form the foundation for all subsequent work including data cleaning, exploratory analysis, visualization, and machine learning. Time invested in deeply understanding DataFrame operations pays continuous dividends throughout your entire data science career.