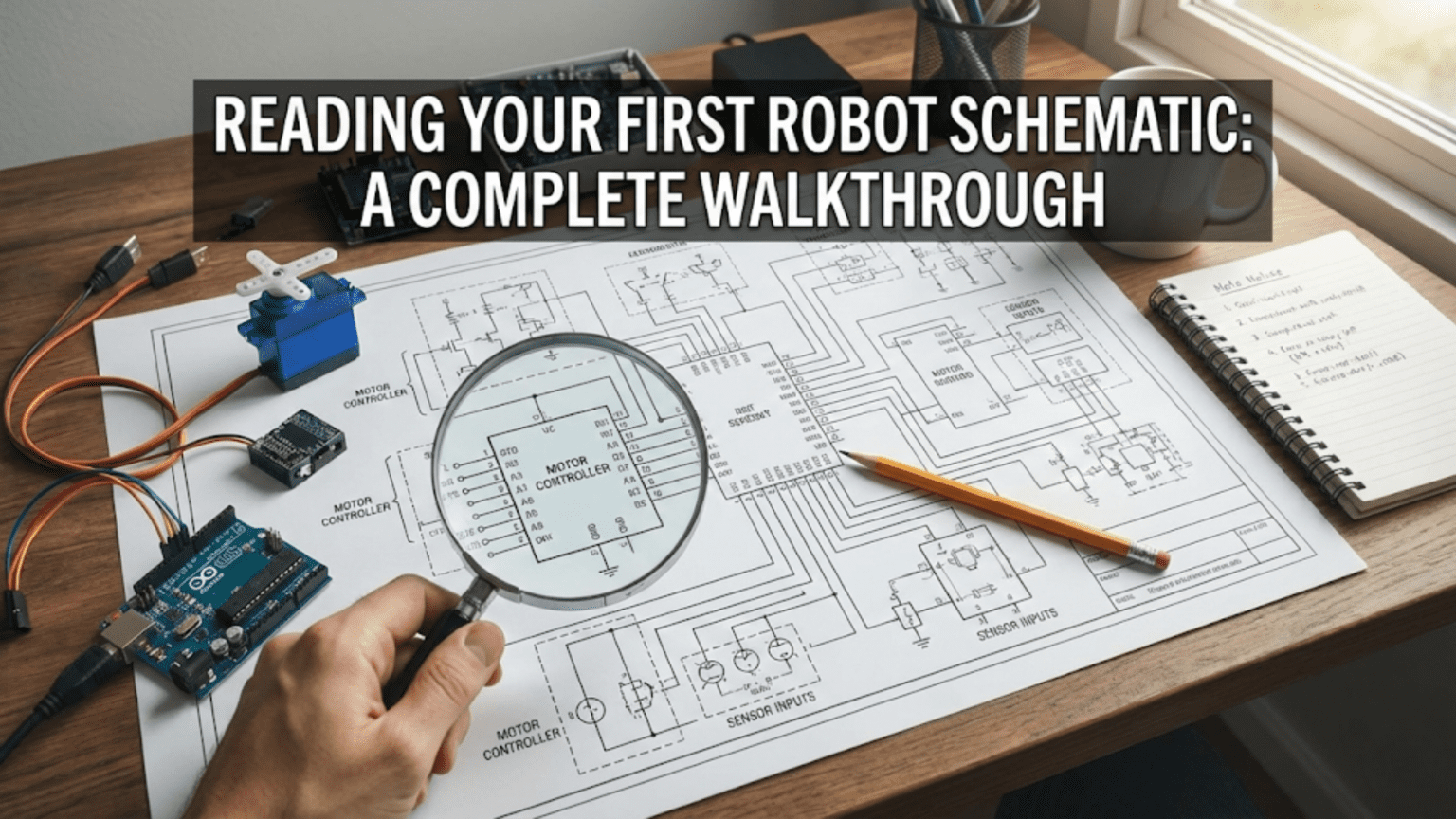

When you first encounter a robot schematic or circuit diagram, the experience can feel overwhelming. Lines connecting cryptic symbols, mysterious labels like “R1” and “C3,” reference designators, voltage annotations, and component values create what appears to be an impenetrable technical language. Yet engineers and experienced roboticists glance at these same diagrams and immediately understand how circuits function, what components do, and how everything connects together. Learning to read schematics transforms from a intimidating barrier into an empowering skill that opens your understanding of how robots actually work at the electronic level.

Schematics serve as the universal language of electronics, communicating circuit designs across language barriers and cultural boundaries. An engineer in Japan and a hobbyist in Brazil can both understand the same schematic despite speaking different languages, because standardized symbols and conventions create shared meaning. When you build robots from kits, modify existing designs, or create your own circuits, schematics provide the roadmap showing what connects to what and how components interact. Without the ability to read schematics, you remain dependent on pre-built modules and detailed assembly instructions. With schematic literacy, you gain independence to understand, modify, and create electronic systems.

This article provides a complete walkthrough of robot schematic reading, starting from absolute basics and building systematic understanding of symbols, conventions, and interpretation techniques. You will learn what different symbols represent, how to trace signal paths through circuits, how to identify power connections, and how to understand component relationships. By the end, you will be able to look at a robot schematic and extract meaningful understanding of how the circuit functions, what each component contributes, and how you might modify or troubleshoot the design.

What Schematics Actually Show

Before diving into specific symbols and conventions, understanding what schematics represent fundamentally helps clarify their purpose and limitations. A schematic is an abstract diagram showing electrical connections between components, not a physical representation of how components physically arrange on a circuit board. Two components appearing next to each other in a schematic might sit on opposite sides of an actual circuit board, while components drawn far apart might be physically adjacent. This abstraction focuses attention on electrical function rather than physical layout.

The schematic shows every electrical connection in the circuit through lines representing wires or traces. When you see a line connecting two component symbols, that means those components electrically connect, allowing current to flow between them. Where multiple lines meet at a junction marked with a dot, all those connections join together electrically. When lines cross without a junction dot, they pass over each other without connecting, like highway overpasses where roads cross at different heights without intersecting.

Component symbols represent actual physical components like resistors, capacitors, transistors, or integrated circuits. Each symbol follows standardized designs that suggest the component’s function or appearance while remaining abstract enough to represent any specific part of that type. A resistor symbol looks like a zigzag or rectangle, suggesting something that impedes current flow. A capacitor symbol shows two parallel lines, representing the parallel plates inside actual capacitors. These visual mnemonics help you remember symbols once you learn them.

Labels and reference designators identify specific components. Rather than just showing “a resistor,” the schematic marks it as “R1,” “R2,” etc., allowing documentation to reference specific resistors. Component values appear near symbols, telling you “10kΩ” for a resistor’s resistance or “100µF” for a capacitor’s capacitance. These values let you select appropriate components when building the circuit or understand the circuit’s behavior when analyzing it.

Power and ground symbols indicate connections to power supplies and common return paths. Rather than drawing explicit wires connecting every component to power and ground, which would create messy tangles of lines, schematics use symbols to indicate these connections implicitly. A component with a power symbol connects to the power supply voltage wherever that symbol appears, even without visible connecting lines. This convention dramatically simplifies schematic appearance while maintaining clear meaning.

Basic Component Symbols You Must Know

Learning component symbols forms the foundation of schematic literacy. While hundreds of specialized symbols exist for uncommon components, knowing perhaps twenty common symbols enables you to understand the majority of robot schematics. These basic symbols appear repeatedly in circuit designs, and recognizing them on sight accelerates your schematic reading dramatically.

Resistors appear as either zigzag lines in American schematics or rectangles in international/European schematics. The symbol choice depends on regional convention, but both represent the same thing: a component that resists current flow. Next to the resistor symbol, you will see a value like “1kΩ” or “10K,” indicating the resistance in ohms. Colors bands on physical resistors encode these values, but schematics show values directly for clarity. Resistors serve countless functions including limiting current, dividing voltages, and setting timing in circuits.

Capacitors use two parallel lines of equal length for non-polarized types and parallel lines where one curves for polarized electrolytic capacitors. The curved line indicates the negative terminal, which matters for polarized capacitors that only work when oriented correctly. Capacitor values appear as “100nF,” “10µF,” or similar, indicating capacitance. Capacitors store electrical energy temporarily, filter signals, smooth power supplies, and block DC while passing AC signals.

Inductors or coils show as a series of curves or loops representing wire wrapped around a core. Robotics uses inductors less frequently than resistors and capacitors, but they appear in power supplies, motor circuits, and radio frequency applications. Values indicate inductance in henries, typically millihenries (mH) or microhenries (µH) for practical components.

Diodes appear as triangles pointing toward a line, suggesting current flows in the direction the triangle points while blocking reverse flow. Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) add small arrows pointing away, symbolizing light emission. Diodes rectify alternating current to direct current, protect circuits from reverse voltage, and emit light for indicators. The line marks the cathode (negative) side while the triangle points toward the anode (positive).

Transistors come in several symbol variations depending on type. Bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) show as a circle containing a diagonal line with two lines extending from it, and an arrow on one line indicating direction and transistor type (NPN or PNP). Field-effect transistors (FETs) use different symbols with three terminals labeled gate, source, and drain. Transistors amplify signals or act as electronic switches, essential for controlling motors, driving LEDs, and building logic circuits.

Integrated circuits and microcontrollers appear as rectangles with pins extending from the sides. Labels inside identify the specific chip like “ATmega328” or “L293D.” Pin numbers or names appear outside the rectangle next to each line. Unlike simpler components with universal symbols, IC symbols vary based on the specific chip but follow this general rectangular convention with labeled connections.

Switches show as a line that can make or break connection, often with a diagonal line indicating the movable contact. Push buttons, toggle switches, and other switch types use related symbols suggesting their mechanical operation. Switches allow manual control of circuits, providing user input or enabling/disabling circuit sections.

Connectors and terminals appear as circles, half-circles, or rectangles with pins, representing physical connection points where wires attach or boards interconnect. These symbols show where your circuit interfaces with external components like sensors, motors, or power supplies.

Batteries or power sources use multiple parallel lines of alternating lengths, suggesting stacked cells in actual batteries. The longer line indicates positive, shorter negative. Sometimes schematics simply show voltage labels like “+5V” or “+12V” to indicate power connections without drawing an actual battery symbol.

Ground symbols take several forms but commonly show as three horizontal lines decreasing in length, creating a triangle-like appearance, or a flag-like symbol. Ground represents the circuit’s zero-volt reference point and return path for current. All grounds in a schematic connect together electrically even without drawn connections.

Understanding Connections and Junctions

The lines in schematics represent electrical connections, but understanding how to interpret these lines requires knowing several important conventions about junctions, crossings, and implicit connections.

When three or more lines meet at a point, a dot typically marks the junction, indicating all lines connect together electrically. This junction dot serves as crucial indicator—it shows that current can flow between all the connected paths. Without the dot, lines might simply cross without connecting, so the dot’s presence confirms intentional connection.

When two lines cross without a junction dot, they pass over each other without electrical connection. Think of highway overpasses where roads cross at different levels—vehicles cannot transfer between the crossing roads without an explicit ramp. Similarly, schematic lines can cross without connecting, letting designers draw cleaner diagrams without avoiding all potential crossings. Some schematics draw a small semicircular bridge where lines cross without connecting, explicitly showing the non-connection, though this convention is becoming less common as junction dots became standard for indicating connections.

Net labels or node names sometimes replace actual drawn connections for frequently used signals or to avoid excessive line clutter. If you see the same label like “MOTOR_A” appearing at multiple points in the schematic, all those labeled points connect together electrically even without visible lines between them. This convention particularly helps when a signal needs to reach many destinations, where drawing all the physical lines would create a tangled mess.

Power supply connections frequently use implicit connections through voltage symbols. Rather than drawing lines from a power supply to every component needing power, schematics place “+5V” symbols at each point needing 5-volt power. These symbols indicate connection to the 5-volt supply wherever they appear. Similarly, ground symbols connect all ground points together implicitly. This simplification dramatically reduces visual clutter while maintaining precise meaning.

Bus notation bundles multiple related signals into a single thick line with a slash and number indicating how many signals it represents. In complex circuits with many data lines or address lines, showing each one separately would create overwhelming complexity. A bus labeled “D[0:7]/8” indicates eight data lines bundled together. Individual signals can branch off the bus using thinner lines.

Tracing Signal Flow Through Circuits

Once you recognize symbols and connections, tracing how signals flow through circuits helps you understand what the circuit actually does. Following signal paths reveals cause-and-effect relationships where input changes propagate through components producing desired outputs.

Start by identifying inputs and outputs in the schematic. Inputs might be labeled explicitly as “INPUT,” connect to sensor symbols, or come from user controls like switches or potentiometers. Outputs typically drive actuators like motors or LEDs, connect to output terminals, or feed into other subsystems. Understanding what enters and exits the circuit provides context for understanding intermediate components.

Follow connections from inputs through successive components toward outputs. Each component transforms or processes signals in specific ways based on its type and configuration. A resistor might divide voltage. A transistor might amplify current. An integrated circuit might convert analog sensor signals to digital values. Understanding these component functions helps you comprehend the overall circuit operation.

Power flow traces differently than signals. Current flows from the positive power supply through components to ground, completing the circuit. Some components connect between power and ground, drawing continuous current. Others connect in series with signals, only drawing current when activated. Distinguishing power paths from signal paths clarifies which connections carry continuous power versus those that carry variable signals.

Control signals often show as inputs to transistors, integrated circuits, or switches that influence other parts of the circuit. A microcontroller pin might control a transistor that switches motor power on and off. Following these control relationships shows how the circuit’s brain commands its muscles and responds to sensors.

Feedback paths show where outputs influence inputs, creating closed control loops. A motor driver circuit might include current sensing that feeds back to the controller, allowing current limiting. Temperature sensors might control cooling fans in feedback loops maintaining desired temperatures. Identifying these feedback paths reveals self-regulating behaviors.

Understanding Component Values and Ratings

Numbers and units appearing next to component symbols specify critical characteristics that determine circuit behavior. Learning to interpret these values helps you understand why specific components were chosen and predict how the circuit behaves.

Resistor values appear as numbers with unit multipliers. “10kΩ” means 10,000 ohms. “100Ω” means 100 ohms. The letter “R” sometimes replaces the decimal point, so “4R7” means 4.7 ohms. Standard resistor values follow specific series like E12 or E24, explaining why you see values like 4.7, 10, 22, 47 rather than round numbers like 5, 10, 20, 50. Understanding common values helps you recognize typical resistance ranges.

Capacitor values use farads, but practical capacitors measure in microfarads (µF), nanofarads (nF), or picofarads (pF). “100µF” equals 100 microfarads, a common value for power supply filtering. “100nF” equals 0.1 microfarads, typical for signal decoupling. Be careful with unit multipliers—missing a prefix dramatically changes the value. Voltage ratings also matter for capacitors; a capacitor marked “25V” only works safely up to 25 volts.

Transistor specifications become relevant when you need to select or replace components. Current ratings indicate maximum current the transistor can handle. Voltage ratings specify maximum voltages. Gain values indicate amplification factor. While schematics might not show all these specifications, they appear in component datasheets that schematics reference through part numbers.

Integrated circuit pin functions require datasheets for full understanding. While schematics label pins, you need datasheets to understand what each pin does, what voltages it expects, and how to configure the chip. A pin labeled “EN” might enable the chip, but the datasheet specifies whether high or low voltage enables it.

Power supply voltages noted throughout schematics like “+5V,” “+12V,” or “+3.3V” indicate what voltage that circuit section requires. Robots often use multiple voltages—low voltage for logic circuits and higher voltage for motors. Understanding these voltage domains helps you recognize power supply requirements and avoid connecting incompatible voltages.

Subsystem Blocks and Circuit Organization

Complex robot schematics often organize into subsystems or blocks, each handling specific functions. Recognizing these organizational patterns helps you navigate large schematics without becoming lost in details.

Power supply sections convert battery voltage or wall power into regulated voltages other circuits need. Look for voltage regulators, filter capacitors, and connections distributing power to other sections. These sections typically appear at one side of a schematic, clearly separated from signal processing areas.

Microcontroller or processor sections show the robot’s brain with connections to sensors, communication ports, and control outputs. Surrounding components might include clock crystals, reset circuits, and decoupling capacitors. This central section typically connects to many other subsystems.

Motor driver circuits accept low-power control signals from the microcontroller and amplify them to switch high currents for motors. H-bridge circuits allowing bidirectional motor control often appear here, using multiple transistors or dedicated motor driver ICs. Current sensing resistors might provide feedback.

Sensor interface circuits condition sensor signals for the microcontroller. This might include voltage dividers scaling voltages to safe ranges, filters removing noise, or amplifiers boosting weak signals. Each sensor might have dedicated interface circuitry near its connection point.

Communication interfaces handle data exchange with other devices. USB connections, wireless modules, or serial ports appear in these sections with level-shifting circuits and protection components ensuring reliable communication.

Protection and safety circuits include reverse voltage protection diodes, fuses, voltage clamps, and current limiters. These components protect against connection errors, voltage spikes, or fault conditions. They typically appear near power inputs and between subsystems.

Practical Schematic Reading Exercise

Let’s work through reading a simple motor control schematic to practice these concepts. Imagine a schematic showing a microcontroller controlling a DC motor through a transistor.

Starting at the microcontroller, you see a pin labeled “MOTOR_CTRL” connecting through a resistor marked “1kΩ” to a transistor’s base terminal. This resistor limits current into the transistor, protecting both the microcontroller and transistor. The transistor symbol shows it’s an NPN type with the emitter connecting to ground through a ground symbol.

The transistor’s collector connects to one motor terminal. The motor’s other terminal connects to a “+12V” power symbol. In this configuration, when the microcontroller output goes high, current flows through the base resistor into the transistor base, turning the transistor on. This allows current to flow from the 12V supply through the motor and through the transistor to ground, running the motor.

A diode appears across the motor with its cathode toward the 12V supply and anode toward the transistor. This flyback diode protects the transistor from voltage spikes when the motor turns off. Motors generate reverse voltage when switched off due to collapsing magnetic fields; the diode safely dissipates this energy.

This simple schematic demonstrates key concepts: identifying component types by symbols, following signal paths from microcontroller through transistor to motor, recognizing power connections through voltage symbols, and understanding protection components like the current-limiting resistor and flyback diode.

Common Schematic Reading Mistakes

Understanding common mistakes helps you avoid them and troubleshoot when circuits don’t work as expected.

Confusing schematics with physical layouts leads to incorrect assembly. Components appearing adjacent in schematics might not mount near each other physically. Always follow the schematic’s electrical connections rather than assuming physical proximity from schematic arrangement.

Missing junction dots causes connection errors. If lines cross with a dot, they connect. Without the dot, they usually don’t connect. Carefully check for junction dots at every line intersection to determine intended connections.

Ignoring polarity on polarized components damages them. Electrolytic capacitors, diodes, and batteries have specific orientations that schematics indicate through symbol orientation or markings. Connecting them backwards typically destroys them or prevents circuit operation.

Misreading unit multipliers causes value errors. Confusing microfarads with nanofarads or kiloohms with megohms results in component values off by factors of 1000, dramatically changing circuit behavior.

Assuming all grounds are identical works in simple circuits but fails in complex designs that might have separate analog and digital grounds or isolated ground planes. Pay attention to ground symbol variations and net labels that might indicate separate ground domains.

Building Schematic Reading Confidence

Improving schematic literacy requires practice with progressively complex diagrams. Start with simple circuits having few components and clear signal paths. Analyze circuit operation, identifying inputs, outputs, and what each component contributes.

Redraw schematics by hand to internalize component symbols and connection conventions. This active engagement builds familiarity faster than passive reading. Your drawings need not be artistic—focus on correct symbols and connections.

Compare schematics to physical circuits or photographs of assembled boards. Matching schematic connections to actual wires and components reinforces understanding of how abstract diagrams represent concrete implementations.

Study annotated schematics where designers added notes explaining circuit operation. These annotations provide valuable learning about why specific components were chosen and how subsections interact.

Use simulation software that requires building circuits from schematics. Virtual breadboarding tools let you connect schematic components, then simulate circuit operation, providing immediate feedback about whether you interpreted connections correctly.

Ask questions in robotics forums when specific schematic aspects confuse you. Experienced builders can clarify conventions or explain component functions, accelerating your learning beyond what solitary study achieves.

From Reading to Creating

Schematic literacy eventually enables you to create your own schematics documenting custom circuits. Understanding how to read schematics naturally leads to understanding how to draw them clearly. The same conventions you learned for reading—clear component symbols, junction dots, organized layout—become guidelines for creating readable schematics others can understand.

When you reach the point of designing custom robot circuits, schematic drawing software helps you create professional-looking diagrams. Tools like KiCad, Eagle, or EasyEDA provide symbol libraries, automatic connection checking, and the ability to generate circuit boards from schematics. Learning these tools typically happens after you understand schematic reading fundamentals, as you need to know what you want to draw before learning how to draw it.

The progression from reading simple schematics to understanding complex robotic systems to creating your own circuit designs reflects growing competence in electronics. Each robot schematic you successfully read builds your symbol vocabulary, reinforces connection conventions, and expands your understanding of how circuits accomplish specific functions. This accumulated knowledge eventually lets you look at any robot electronics, trace the schematic, understand the design choices, and potentially improve or modify the circuit for your specific needs.

Reading schematics transforms from an intimidating barrier into an empowering skill that deepens your understanding of how robots work at the fundamental electronic level. Every schematic you successfully interpret adds to your technical knowledge, making subsequent schematics easier to understand. The universal language of electronic schematics opens countless learning opportunities—you can study circuits in online repositories, learn from open-source robot designs, understand commercial products through published schematics, and eventually create your own circuit designs that others might learn from in turn.