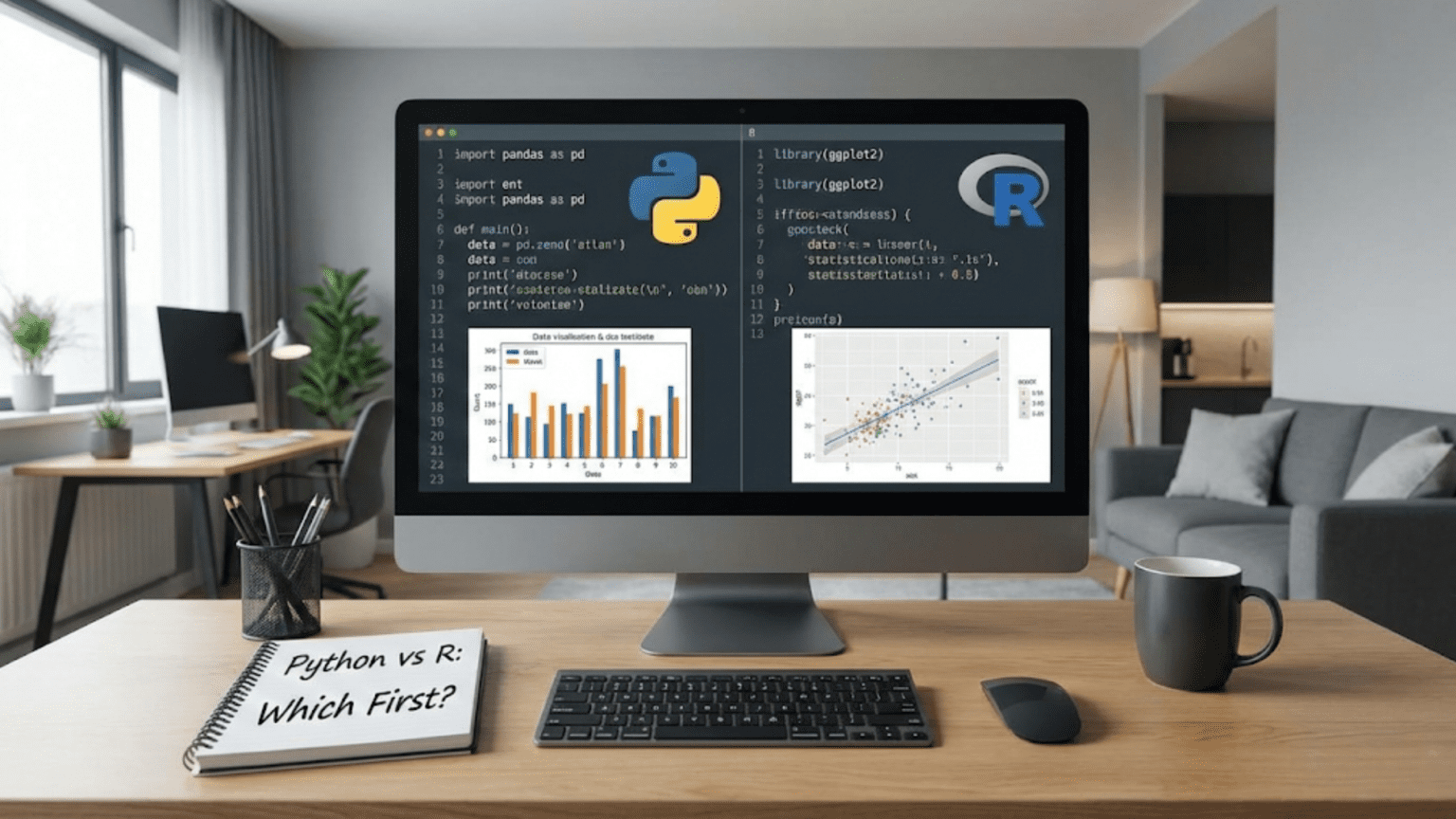

The Question That Divides Data Science Beginners

You have decided to learn data science and everyone agrees that programming is essential. Then you encounter the first major fork in the road: Python or R? You research the question and find passionate advocates for both sides. Python enthusiasts tout its versatility, clean syntax, and dominance in production systems. R advocates emphasize its statistical power, specialized packages, and academic pedigree. Both camps present compelling arguments, leaving you more confused than when you started.

This decision paralysis affects countless aspiring data scientists. You worry that choosing wrong will waste months learning the inferior language before having to start over. You fear missing out on opportunities because you picked the less popular option. The stakes feel high because learning a programming language requires substantial time investment, and you want that investment to pay off.

The good news is that this decision matters less than you think, and there is no universally correct answer. Both Python and R are excellent choices for data science, used successfully by professionals across industries. The better question is not which language is objectively superior but which better matches your specific goals, background, and working style. Let me guide you through an honest comparison that will help you make an informed decision based on your situation rather than abstract arguments about which language is better.

Understanding the Origins and Philosophies

To understand the differences between Python and R, we need to look at where they came from and what problems they were designed to solve. These origins shaped each language’s strengths and weaknesses in ways that persist today.

Python emerged in the late 1980s as a general-purpose programming language designed to be readable and versatile. Guido van Rossum, Python’s creator, emphasized code clarity and elegant design that makes programs easy to read and understand. Python was never specifically designed for data science or statistics. Instead, it was built as a flexible tool for diverse programming tasks from web development to automation to scientific computing. Its data science capabilities came later through libraries created by the community.

This general-purpose heritage gives Python certain characteristics. The language itself contains few statistical functions because statistics was not the original focus. Instead, Python provides a clean, expressive core language that libraries extend with specialized functionality. This design means you can use Python for data science today and web development tomorrow without learning an entirely different language. The skills transfer across domains.

R, in contrast, was created in the early 1990s specifically for statistical computing and graphics. Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman built R as an open-source implementation of the S language, which itself emerged from Bell Labs for statistical analysis. From the beginning, R focused narrowly on statistical analysis and visualization. Its design reflects assumptions about what statisticians need, with built-in functions for statistical operations that require external libraries in Python.

This specialized heritage shapes R’s character. Statistical concepts are first-class citizens in the language. Probability distributions, hypothesis tests, and statistical models have dedicated syntax and conventions. The language evolved primarily within academic statistics departments, leading to design choices that statisticians appreciate but programmers sometimes find quirky. R excels within its domain of statistical analysis while Python excels at being adaptable across domains.

Neither heritage is inherently better. They represent different design philosophies suited to different contexts. Understanding these philosophies helps you appreciate why each language makes certain choices and which might align better with your needs.

Syntax and Learning Curve: Which is Easier to Start?

For complete beginners with no programming experience, the initial learning curve differs between Python and R in ways that might influence your choice, though both are learnable with dedication.

Python’s syntax is often praised for readability that approaches natural language. Code like if temperature > 30: print("It's hot") reads almost like English. The language enforces indentation for code blocks, which forces you to format code neatly from the start and makes structure visually obvious. This opinionated approach to formatting helps beginners write readable code even before they fully understand why certain styles are better.

Python follows object-oriented principles consistently, with most things being objects that have methods. Once you grasp this concept, it applies broadly across the language. The pandas library, for example, treats datasets as DataFrame objects with methods for manipulation. This consistency means that learning one part of Python helps you understand other parts because similar patterns repeat.

R’s syntax reflects its statistical heritage, which can feel less intuitive if you come from outside statistics. The language uses several different assignment operators like <-, =, and ->, though <- is conventional. Functions often use formulas specified with the tilde operator like lm(y ~ x + z) for linear models, which statisticians recognize immediately but confuses newcomers. Special operators like %>% for piping operations in the tidyverse add power but require learning new concepts.

However, R’s base language includes many statistical functions that Python requires libraries for, which can make initial statistical work simpler in R. Calculating a correlation in base R is just cor(x, y) while Python requires importing pandas or numpy. For someone focused purely on statistical analysis from day one, R’s built-in statistical capabilities provide a gentler start than loading Python libraries.

Both languages have excellent learning resources, though Python’s broader use beyond data science means more general programming tutorials exist. R’s resources tend to focus specifically on statistical applications, which can be helpful if that matches your goals but limiting if you want broader programming knowledge.

Realistically, if you are committed to learning, you can master either language. The initial syntax differences matter less than sustained effort over months. Most people find Python slightly more intuitive initially, but both become natural with practice. Your choice should depend more on where you want to use the language than which seems easier in week one.

Data Manipulation and Analysis: Tools and Workflows

How you actually work with data day-to-day differs between Python and R ecosystems, with each offering powerful but distinct approaches to common tasks.

Python’s pandas library has become the standard for data manipulation, providing DataFrame objects that hold tabular data with rich methods for filtering, grouping, joining, and transforming. Pandas borrows concepts from R but implements them with object-oriented Python syntax. You load data with pd.read_csv(), filter with boolean indexing or query methods, group with groupby(), and chain operations together. The library is powerful but has a learning curve, with multiple ways to accomplish the same task that can confuse beginners.

NumPy underlies pandas, providing fast array operations that make Python competitive with compiled languages for numerical computing. When you work with large numerical datasets, NumPy’s vectorized operations run efficiently. This foundation means Python can handle substantial data volumes effectively, especially when combined with libraries like Dask for parallel computing.

R offers two main paradigms for data manipulation. Base R provides built-in functions and syntax that work without additional packages, using bracket notation for subsetting and built-in functions for transformations. The tidyverse, a collection of packages including dplyr for manipulation and ggplot2 for visualization, offers an alternative approach that many find more intuitive. Tidyverse code uses pipes %>% to chain operations, making data transformation read like a recipe: “take this data, then filter it, then group it, then summarize it.”

The tidyverse has gained enormous popularity because it provides a consistent grammar across different data operations. Once you learn the core verbs like filter, select, mutate, group_by, and summarize, you can accomplish most data manipulation tasks. The approach feels declarative, stating what you want rather than how to get it. Many R users prefer tidyverse so strongly that they rarely use base R for data manipulation.

For statistical analysis, R’s advantage is clearer. Statistical models in R often require less code because the language was designed for this purpose. Running a linear regression in R is lm(y ~ x1 + x2) and the formula syntax extends naturally to complex models. Python’s statsmodels provides similar functionality but with more verbose syntax that reflects its add-on nature rather than being built into the language.

Both languages handle missing data, outliers, and data quality issues well, with comprehensive functions for detection and treatment. Both can work with various data formats from CSV to databases to web APIs. The practical difference comes down to syntax preferences and which ecosystem’s tools you prefer rather than fundamental capability differences.

Visualization: Telling Stories with Data

Creating effective visualizations is crucial for both exploration and communication, and Python and R offer different approaches with different strengths.

Python provides multiple visualization libraries, each serving different purposes. Matplotlib is the foundational library offering fine-grained control over every aspect of plots but requiring more code for common tasks. Seaborn builds on Matplotlib, providing higher-level interfaces for statistical visualizations with sensible defaults. Plotly enables interactive visualizations that users can explore dynamically. This ecosystem gives you flexibility but requires learning multiple libraries and knowing which to use when.

Matplotlib’s object-oriented approach can confuse beginners who encounter different ways to create plots. The library offers both MATLAB-style pyplot interface and object-oriented APIs, and tutorials mix both approaches. Once you understand the underlying structure, you can create virtually any visualization, but the learning curve is steep. Seaborn simplifies common statistical plots significantly, making it a better starting point for most data science work.

R’s ggplot2 has become the gold standard for statistical graphics, implementing Leland Wilkinson’s grammar of graphics philosophy. This approach treats visualizations as compositions of layers representing data, aesthetics, geometries, and themes. You build plots by adding components: start with data, map variables to visual properties like position or color, add geometric objects like points or lines, and customize appearance with themes.

The grammar of graphics approach makes ggplot2 remarkably powerful once you understand its logic. You can create complex, publication-quality visualizations with relatively little code. The same conceptual framework applies whether you are making scatter plots, box plots, or faceted multi-panel displays. This consistency helps you learn faster and accomplish more complex visualizations than would be practical with imperative approaches.

For exploratory analysis during development, both languages serve well. For publication-quality static graphics, particularly for academic papers, ggplot2 has advantages in polish and aesthetics. For interactive dashboards and web applications, Python’s Plotly and Dash or R’s Shiny both work well, with the choice depending more on your comfort with each language than inherent capabilities.

Realistically, you can create excellent visualizations in either language. R’s visualization story is slightly more cohesive with ggplot2 as the clear standard, while Python’s multiple libraries offer flexibility but require more decisions about which tool to use. Your preference might depend on whether you value unified consistent approaches or flexibility with specialized tools.

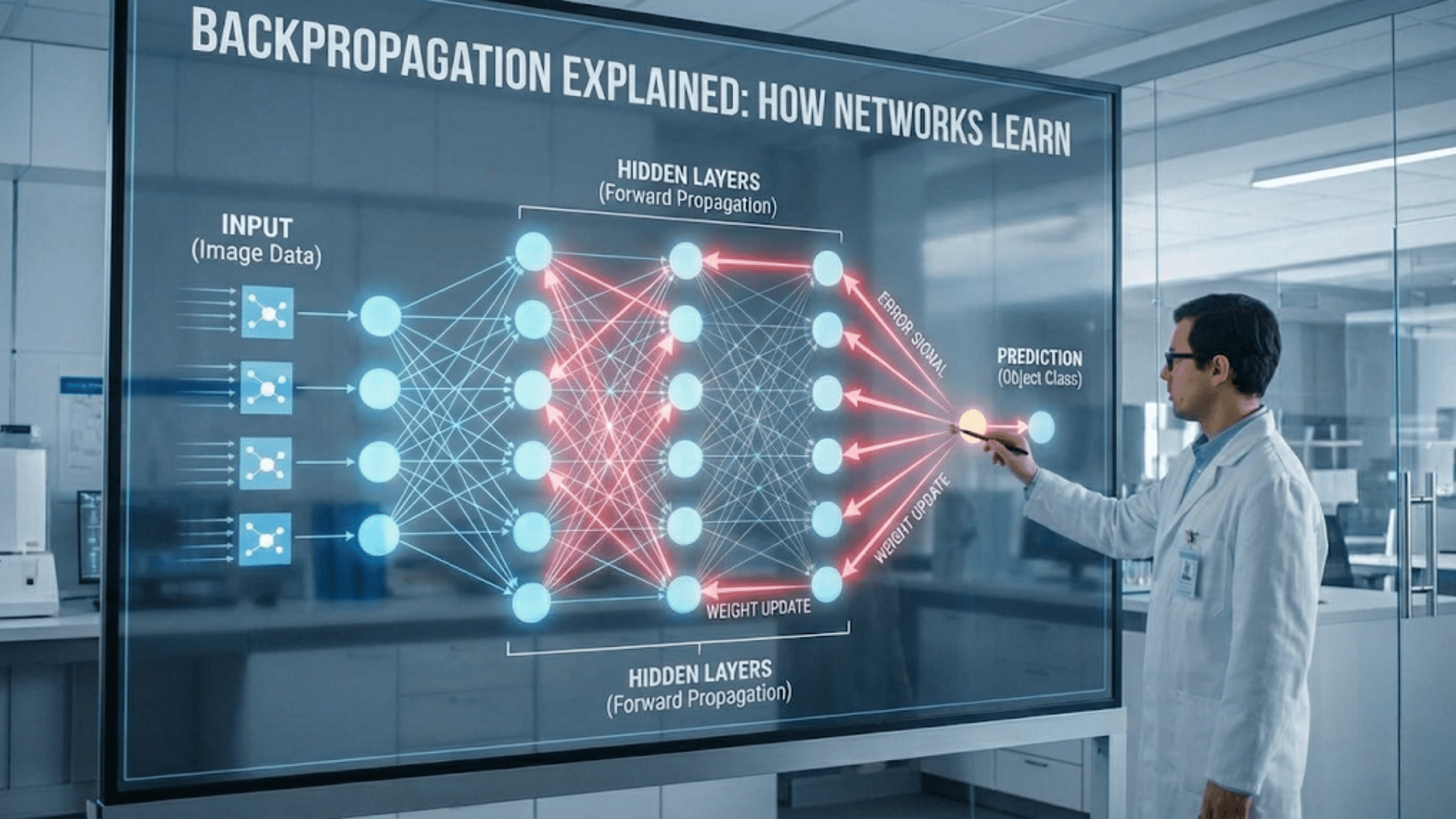

Machine Learning and Advanced Analytics

As you move beyond basic analysis into machine learning and predictive modeling, the ecosystems diverge in ways that might influence your choice.

Python dominates machine learning and deep learning, with scikit-learn providing the standard implementation of classical algorithms and TensorFlow and PyTorch leading deep learning frameworks. Companies developing cutting-edge machine learning research release Python libraries first and sometimes exclusively. If you want to work with the latest techniques in computer vision, natural language processing, or reinforcement learning, you will likely use Python.

Scikit-learn offers a consistent API across dozens of algorithms, making it easy to try different approaches. The same basic pattern of fitting models and making predictions applies whether you use linear regression or neural networks. Extensive documentation and examples help you learn each algorithm. The library emphasizes practical machine learning over theoretical purity, which suits many applied data scientists.

R provides machine learning capabilities through packages like caret, which offers a unified interface to hundreds of different algorithms, and mlr3, a modern framework for machine learning workflows. These packages are powerful and well-designed, but the ecosystem feels less vibrant than Python’s. New research often appears in Python first, and some cutting-edge methods have no R equivalent or only after significant delays.

For deep learning specifically, Python is essentially the only serious choice. TensorFlow and PyTorch, the dominant frameworks, are Python-first with limited or no R support. Computer vision libraries, natural language processing tools, and reinforcement learning frameworks overwhelmingly use Python. If deep learning is important to your goals, Python is the clear choice.

However, for traditional statistical learning and certain specialized statistical methods, R maintains advantages. Bayesian statistics, survival analysis, time series forecasting, and mixed effects models often have better implementations in R with more mature packages developed by statisticians. If your work emphasizes these traditional statistical methods over modern machine learning, R might serve you better.

Both languages integrate with big data technologies, though Python’s broader adoption in engineering contexts gives it an edge. Spark, the leading big data processing framework, has excellent Python integration through PySpark. Dask brings parallel computing to Python pandas. R has its own big data tools, but integration with enterprise data infrastructure tends to be smoother with Python.

Career Opportunities and Industry Adoption

Practical career considerations should influence your language choice, as job opportunities and industry preferences vary between Python and R.

Python has become the dominant language in data science job postings, appearing in roughly seventy to eighty percent of data scientist positions based on various job market analyses. Companies across all industries from technology to finance to healthcare list Python as required or preferred. This dominance reflects Python’s versatility, making it useful beyond data science for tasks like web development, automation, and infrastructure management.

Tech companies particularly favor Python, with giants like Google, Facebook, and Amazon building much of their infrastructure around it. Startups typically choose Python for its flexibility and the large talent pool. Even organizations that also use R often list Python as primary with R as secondary. For someone seeking the broadest possible job market access, Python is the safer choice.

R maintains strong presence in specific domains, particularly academic research, pharmaceuticals, and specialized statistics roles. Research institutions, biostatistics departments, and pharma companies conducting clinical trials often prefer R because their existing codebases and statistical methodologies were built in R. Consulting firms that focus on statistical analysis sometimes favor R for its statistical capabilities.

However, R’s job market is smaller and more specialized than Python’s. You can absolutely build a successful career using primarily R, but you will have fewer opportunities to choose from. Many R users also learn Python to expand their options, while fewer Python users feel compelled to learn R, which tells you something about market dynamics.

Salary data shows little difference between Python and R practitioners at comparable experience levels. Both languages can lead to well-compensated careers. The difference is more about opportunity volume than compensation level.

For freelancing and consulting, Python’s broader applicability beyond data science can be advantageous. A Python data scientist can also take on web scraping, automation, or API development projects. R specialists find their opportunities concentrated in data analysis and statistics, which provides plenty of work but less variety.

Geographic location matters too. Tech hubs like San Francisco, Seattle, and New York heavily favor Python. Academic centers and areas with strong pharmaceutical industries have more R opportunities. Understanding your local job market can inform your decision.

Integration and Production Deployment

How easily you can integrate your work into broader systems and deploy models to production differs significantly between Python and R, which matters if you aim for roles involving production systems.

Python integrates seamlessly with software engineering workflows because it is a general-purpose language that engineers already use. Data scientists and software engineers speak the same language, making collaboration smoother. When you need to deploy a machine learning model to an API that serves predictions, Python’s web frameworks like Flask or FastAPI make this straightforward. The model and the API can both be written in Python.

Python’s maturity in software engineering means better tooling for production concerns like testing, logging, monitoring, and version control. Tools like Docker for containerization work excellently with Python. Cloud platforms provide first-class Python support. Continuous integration and deployment pipelines handle Python well because these tools were often built for Python in the first place.

R can be deployed to production, and tools like Plumber create APIs from R code, but it feels more like adapting a statistical tool for engineering purposes rather than using a language designed for this. Engineering teams at many companies are less familiar with R, creating communication gaps and integration challenges. Deploying R in production often means translating models to Python or wrapping R in ways that engineers find awkward.

For creating dashboards and interactive applications, R’s Shiny framework is powerful and beloved by many R users. You can create sophisticated interactive applications entirely in R without learning web technologies. Python’s Dash and Streamlit offer similar capabilities with different approaches. All three frameworks enable creating dashboards without deep web development knowledge, though each has its learning curve and tradeoffs.

If your work stays primarily within analytical notebooks shared with other data scientists, integration concerns matter less. Jupyter notebooks work with both Python and R (the “R” in Jupyter stands for R, after all). RMarkdown provides excellent notebooks for R users. Both languages can produce reports, analyses, and visualizations for consumption by non-technical stakeholders.

However, if you envision building systems that automatically make predictions, power real-time applications, or integrate deeply with software products, Python’s engineering advantages matter significantly. The path from analysis to production is smoother, the tooling is better, and you will face fewer integration challenges.

Learning Resources and Community Support

The availability of learning resources and community support affects how easily you can learn and solve problems that arise during your journey.

Python benefits from being widely used beyond data science, meaning enormous quantities of learning resources exist. Tutorials, courses, books, and videos cover everything from absolute basics to advanced specialized topics. When you search for how to do something in Python, you find multiple explanations at different levels of detail. This abundance helps because you can find resources matching your learning style and background.

The Python data science community is large, active, and welcoming to beginners. Stack Overflow contains hundreds of thousands of questions about pandas, NumPy, and scikit-learn with detailed answers. Reddit’s Python and data science communities are active. Countless blogs share tutorials and insights. When you encounter problems, you can usually find someone who has solved similar issues and shared their solution.

Python’s general-purpose nature means some resources are not data science specific, which can be confusing when learning. You might find tutorials explaining Python concepts for web development that use different libraries than data science workflows. Filtering for data science specific resources helps but requires some judgment about what is relevant.

R’s community is smaller but deeply committed and often academic in orientation. The R community tends to be collegial, with experienced users generously helping newcomers. Resources like R for Data Science, Statistical Learning texts, and RStudio’s extensive documentation provide excellent foundations. The annual useR! conference and regional R meetups foster strong community bonds.

R’s community strength lies in statistical expertise and domain knowledge. When you ask statistical questions, R community members often provide not just code solutions but statistical guidance about whether your approach is appropriate. This statistical depth can be invaluable for learning proper analytical methods alongside coding skills.

Package documentation quality varies in both languages. R packages often include extensive vignettes explaining not just how to use functions but the statistical theory behind them. Python packages range from excellent documentation for major libraries to minimal documentation for smaller packages. In both cases, well-maintained popular packages have good documentation while niche packages vary.

For structured learning, both languages have excellent options. Python has countless courses on platforms like Coursera, edX, and DataCamp. R also has strong course offerings, sometimes with emphasis on statistical concepts alongside programming. University courses teaching statistics often use R, while courses on machine learning and general programming favor Python.

Making Your Decision: A Framework

Given all these considerations, how should you actually decide between Python and R? Here is a framework to guide your choice based on your specific situation.

Choose Python if you want the broadest job market access and most career flexibility. Python appears in far more job postings across all industries and role types. If you are career-switching or entering data science for the first time, Python maximizes your opportunities. You can always learn R later if needed for specific projects, but starting with Python provides the strongest foundation for employment.

Choose Python if you are interested in machine learning, especially deep learning, computer vision, or natural language processing. The ecosystem for these fields is decisively Python-centered. New research and tools appear in Python first and sometimes exclusively. If these areas excite you, Python is essentially mandatory.

Choose Python if you might want to work with production systems, deploy models to APIs, or integrate with software engineering teams. Python’s general-purpose nature and software engineering tooling make deployment smoother. If you envision working closely with engineering teams or in roles that blend data science with software development, Python is the better choice.

Choose R if you work in academia, biostatistics, or clinical research where R is the established standard. Fighting against institutional momentum is difficult, and you will be more effective speaking the same language as colleagues. If R is what your field uses, learn R even if Python might be better abstractly.

Choose R if your work emphasizes traditional statistics, experimental design, or specialized statistical methods. While Python can handle these tasks, R’s statistical depth, specialized packages, and community expertise give it advantages. If you are coming from a statistics background and want to deepen that expertise, R might feel more natural.

Choose R if you prefer a unified, opinionated ecosystem. The tidyverse provides consistent interfaces across data manipulation, visualization, and reporting that many find elegant and intuitive. If you value coherent design philosophy over flexibility, R’s tidyverse offers that experience.

Choose Python if you are unsure and want the safest bet. When in doubt, Python’s broader applicability and larger job market make it the lower-risk choice. You can use Python for data science plus many other things, while R is more specialized. For maximum flexibility, start with Python.

What About Learning Both?

You might reasonably ask whether you should learn both Python and R rather than choosing one. This is absolutely viable, though the timing matters.

Many successful data scientists know both languages, using each where it excels. They might use Python for machine learning and production systems but R for statistical analysis and creating publication graphics. This flexibility is valuable and increasingly common in the field. However, trying to learn both simultaneously as a beginner often leads to confusion and slower progress in both.

The recommended approach is to achieve competence in one language first before adding the second. Spend at least six months to a year becoming comfortable with your first language, learning its core libraries, and completing several projects. Once that foundation is solid, adding the second language is relatively quick because you understand programming concepts and data manipulation workflows. The syntax differs but the logic is similar.

Learning your second language often takes just weeks or months because you are translating concepts you already understand rather than learning from scratch. A Python programmer learning R already knows what data frames are, how grouping and aggregation work, and what different chart types accomplish. They just need to learn R’s syntax for operations they already understand conceptually.

Which to learn first matters less than learning one well before starting the second. Choose based on the factors discussed earlier, commit to that choice for at least six months, and then evaluate whether adding the other language would benefit your specific situation. Many data scientists work successfully knowing only Python or only R, so learning both is optional rather than mandatory.

Conclusion

The Python versus R question has no universally correct answer because both are excellent languages suited to different contexts and preferences. Python offers broader applicability, dominance in machine learning and production systems, and the largest job market. R provides superior statistical depth, elegant tools for traditional statistical analysis, and strong presence in academic and pharmaceutical settings.

For most people entering data science today, especially those seeking broad career options or interested in machine learning, Python is the pragmatic choice. Its general-purpose nature, extensive ecosystem, and industry adoption make it the safer bet. However, R remains the better choice for statistical research, certain specialized domains, and for those who prefer its unified tidyverse ecosystem.

The good news is that choosing one does not preclude learning the other later, and many successful data scientists use both languages, selecting whichever best suits each project. Rather than agonizing over the decision, choose based on your goals and situation, commit to learning that language well, and trust that you can add other languages later if needed.

Your programming language is a tool, not an identity. What matters most is developing strong analytical thinking, understanding statistical concepts, and solving real problems with data. Whether you do that in Python or R is far less important than actually doing it. Make your choice, invest in learning it thoroughly, and get started on your data science journey.

In the next article, we will explore how to set up your first data science development environment, walking through the practical steps of installing Python or R, configuring Jupyter notebooks or RStudio, and preparing your computer for data science work. This will help you move from deciding what to learn to actually learning it.

Key Takeaways

Python emerged as a general-purpose programming language later extended for data science, while R was designed specifically for statistical computing from the beginning. These different origins shape each language’s strengths, with Python excelling at versatility and integration while R excels at statistical depth. Both languages are capable of professional data science work, and the choice depends on your specific goals and context.

Python dominates the job market with seventy to eighty percent of data science positions listing it as required or preferred, making it the safer choice for broad career opportunities. The language has become essentially mandatory for machine learning and deep learning work, with all major frameworks built around Python. Integration with production systems and software engineering workflows is smoother with Python due to its general-purpose nature.

R maintains strong positions in academia, biostatistics, pharmaceutical research, and specialized statistical applications where its statistical depth provides advantages. The tidyverse ecosystem offers elegantly designed tools for data manipulation and visualization that many users prefer to Python’s alternatives. R’s visualization capabilities through ggplot2 are particularly strong for creating publication-quality statistical graphics.

For beginners, learning one language well before attempting the second leads to faster overall progress than trying to learn both simultaneously. Most successful data scientists eventually learn both languages, using each where it excels, but achieving competence in your first choice before adding the second is the recommended path. The programming language is a tool for doing data science, not an end in itself, and strong analytical thinking matters more than which language you use.