Variables form the fundamental building blocks of any program you’ll ever write. Without variables, your programs could only work with fixed values hardcoded into the source, making them inflexible and limited in usefulness. Understanding variables and the data types that define them represents one of the most crucial concepts in programming, and mastering these concepts early in your C++ journey sets you up for success as you tackle increasingly complex programming challenges.

Think of a variable as a labeled container that holds a piece of information your program needs to remember. Just as you might use different types of containers in your kitchen, jars for dry goods, bottles for liquids, containers for leftovers, programming languages use different types of variables to store different kinds of information. The type of a variable determines what kind of information it can hold, how much memory it occupies, and what operations you can perform on it.

In C++, every variable must have a specific type declared before you can use it. This requirement is what makes C++ a statically typed language, meaning the compiler checks that you’re using variables correctly before your program ever runs. This stands in contrast to dynamically typed languages like Python, where variables can change type during program execution. While C++’s type system might seem restrictive at first, it catches many errors during compilation that would otherwise cause problems when your program runs, making your code more reliable and often faster.

Let’s start with the most fundamental data type in C++: the integer, declared with the keyword int. An integer represents whole numbers, numbers without any fractional component. You might use integers to count things, represent ages, track inventory quantities, or store any other whole number value. Here’s how you declare an integer variable:

int age;This statement tells the compiler “create a variable named age that can hold integer values.” The variable exists in your computer’s memory, occupying a specific number of bytes. On most modern systems, an int occupies four bytes (32 bits) of memory, which means it can store values ranging from approximately negative two billion to positive two billion. The exact range is -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647, determined by how binary numbers work in computer memory.

Declaring a variable without giving it an initial value leaves it uninitialized—it contains whatever random data happened to be in that memory location previously. This is a common source of bugs in C++ programs. Reading an uninitialized variable produces unpredictable behavior because you have no way of knowing what value you’ll get. Good practice dictates initializing your variables when you declare them:

int age = 25;This declares the variable age and immediately assigns it the value 25. The equals sign performs assignment in C++, placing the value on the right side into the variable on the left side. From this point forward in your program, whenever you refer to age, you’re accessing the value stored in that memory location. You can change the value later with another assignment:

age = 26; // age now contains 26 instead of 25Modern C++ offers an alternative initialization syntax using curly braces, called uniform initialization or brace initialization:

int age{25};This syntax has advantages over the traditional assignment syntax, particularly in how it handles certain edge cases and prevents accidental narrowing conversions where information might be lost. Many contemporary C++ style guides recommend using brace initialization, though you’ll see both forms in existing code. Understanding both prepares you to read and work with code written in different styles.

You can declare multiple variables of the same type in a single statement, separating them with commas:

int width, height, depth;This creates three separate integer variables. However, initializing multiple variables in one statement can become confusing, especially if you’re only initializing some of them:

int x = 10, y, z = 20; // x is 10, y is uninitialized, z is 20For clarity, especially when learning, declaring each variable on its own line often makes your intentions clearer and reduces the chance of mistakes.

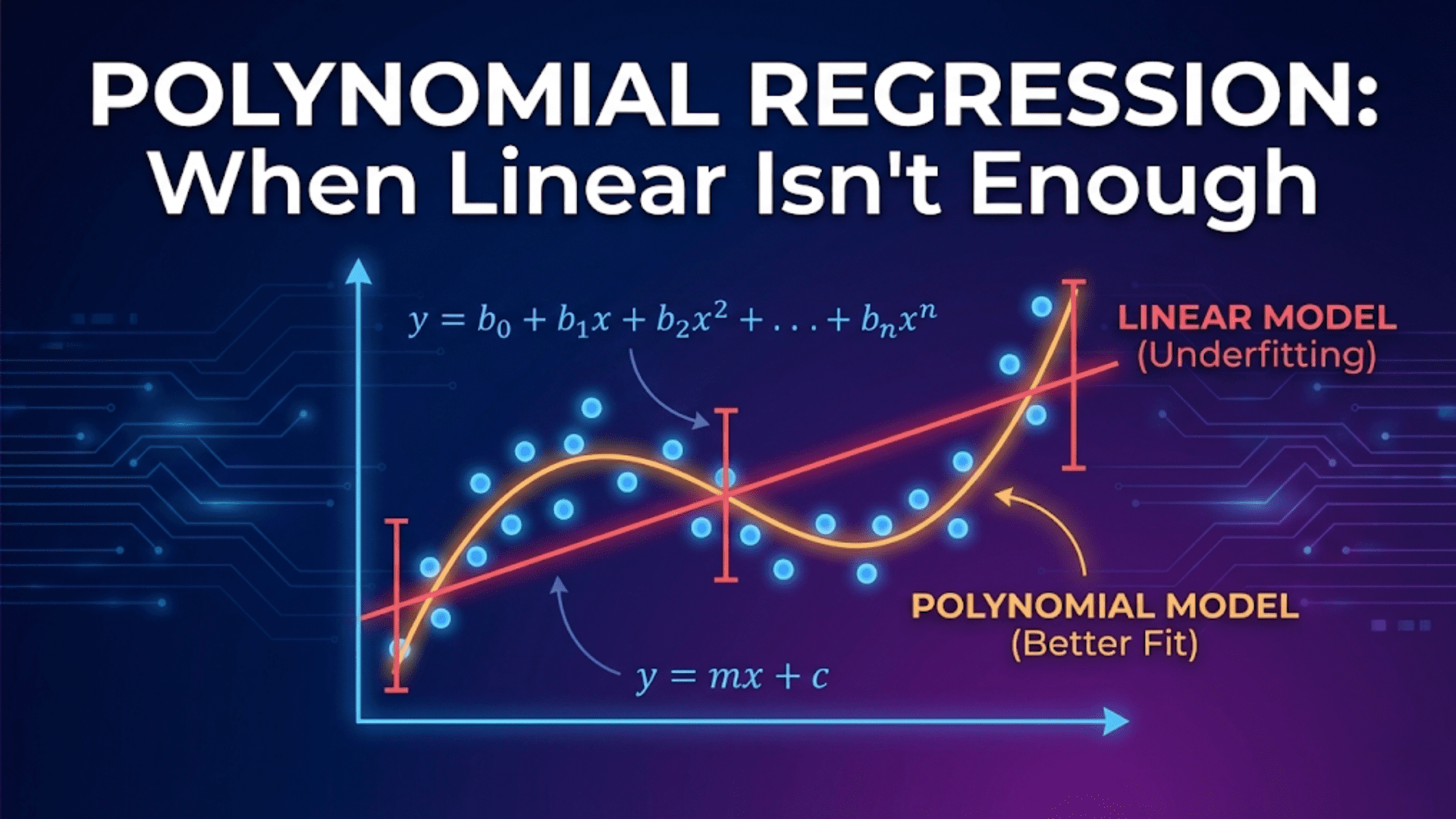

While integers work perfectly for whole numbers, many real-world quantities require fractional values. Your height isn’t exactly five feet—it might be five feet and eleven inches, which you’d express as approximately 5.92 feet. For storing numbers with decimal points, C++ provides floating-point types. The most common are float and double:

float temperature = 98.6;

double pi = 3.14159265359;The difference between float and double lies in their precision and memory usage. A float (short for “floating-point number”) typically occupies four bytes and provides about six to seven decimal digits of precision. A double (short for “double-precision floating-point”) occupies eight bytes and provides about fifteen to sixteen decimal digits of precision. For most applications, double is the preferred choice because the extra precision prevents accumulated rounding errors in calculations, and modern computers handle doubles efficiently.

Understanding how computers store floating-point numbers helps you avoid common pitfalls. Computers represent these numbers in binary, and not all decimal fractions can be represented exactly in binary. This leads to tiny rounding errors that can accumulate in calculations. For example, the decimal number 0.1 cannot be represented exactly as a binary floating-point number, which is why comparing floating-point numbers for exact equality often produces unexpected results. This isn’t a flaw in C++—it’s an inherent characteristic of how binary computers represent decimal fractions.

For storing individual characters—letters, digits, punctuation marks, and symbols—C++ provides the char type (short for “character”):

char grade = 'A';

char initial = 'J';Notice that character values are enclosed in single quotes, not double quotes. Double quotes denote strings (sequences of characters), while single quotes denote individual characters. This distinction is important because ‘A’ and “A” are fundamentally different things to the compiler: ‘A’ is a single character value, while “A” is a string containing one character.

Under the hood, a char actually stores a small integer representing the character according to an encoding system, typically ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange). The character ‘A’ is represented by the number 65, ‘B’ by 66, and so on. This means you can perform arithmetic on characters, though whether this makes sense depends on what you’re trying to accomplish. For example, ‘A’ + 1 produces ‘B’ because you’re adding one to the underlying numeric value.

The char type occupies one byte of memory and can store values from -128 to 127 (for signed char) or 0 to 255 (for unsigned char). This limited range suffices for standard ASCII characters but becomes problematic for international characters in languages with larger character sets. For more comprehensive character handling, C++ provides additional types like wchar_t, char16_t, and char32_t, though beginners typically start with standard char.

Boolean values, represented by the bool type, store logical true or false values:

bool isRaining = true;

bool hasLicense = false;Boolean variables typically occupy one byte of memory, though technically they only need a single bit since they can only represent two states. You’ll use boolean variables extensively when you learn about conditional statements and control flow—they’re perfect for representing the results of comparisons and for tracking the state of conditions in your program.

In C++, any non-zero integer value is considered true when interpreted as a boolean, and zero is considered false. This means you can assign numbers to boolean variables, though doing so makes your code less readable:

bool value = 1; // same as true

bool other = 0; // same as falseWhile technically valid, explicitly using true and false makes your intentions clearer and your code easier to understand.

For storing sequences of characters—words, sentences, names, addresses—C++ provides the string type. Unlike the types we’ve discussed so far, string isn’t a built-in primitive type but rather a class defined in the standard library. To use strings, you need to include the string header:

#include <string>

std::string name = "Alice";

std::string greeting = "Hello, World!";Strings are incredibly versatile, and the string class provides numerous methods for manipulating text—finding substrings, concatenating strings, extracting characters, converting case, and much more. You can use the + operator to concatenate strings:

std::string firstName = "John";

std::string lastName = "Smith";

std::string fullName = firstName + " " + lastName; // "John Smith"You can access individual characters in a string using square bracket notation, with positions numbered starting from zero:

std::string word = "Hello";

char firstChar = word[0]; // 'H'

char secondChar = word[1]; // 'e'The string class also provides a length() method that tells you how many characters the string contains:

std::string message = "Hello";

int messageLength = message.length(); // 5Understanding the distinction between primitive types and class types like string becomes increasingly important as you progress in C++. Primitive types are built into the language and typically map directly to hardware representations. Class types are more complex, providing additional functionality through methods and managing resources like memory automatically. For now, the key understanding is that strings work differently from simpler types like integers and characters, offering richer functionality at the cost of slightly more complexity.

C++ provides several integer types beyond the basic int, each with different size and range characteristics. The short (or short int) type typically occupies two bytes, storing smaller integers than int. The long (or long int) type typically occupies four or eight bytes depending on your system, potentially storing larger values than int. The long long type, introduced in C++11, guarantees at least eight bytes and can store extremely large integers:

short smallNumber = 100;

long bigNumber = 1000000;

long long veryBigNumber = 9223372036854775807;Each of these integer types also comes in an unsigned variant, which cannot represent negative numbers but can represent larger positive values by using the bit that would normally indicate sign to store additional magnitude. You specify unsigned versions with the unsigned keyword:

unsigned int positiveOnly = 4000000000;

unsigned short smallPositive = 65535;Choosing the right integer type involves trade-offs between range and memory usage. In practice, unless you’re working with embedded systems or performance-critical code where every byte matters, using int for general-purpose integer storage works well. Use long long when you know you need to store values larger than two billion, and use unsigned types when you’re certain a value can never be negative and you need the extended positive range.

The concept of variable scope determines where in your program a variable can be accessed. Variables declared inside a function, including main, exist only within that function—they’re destroyed when the function finishes executing. These are called local variables. Variables declared outside any function exist for the entire duration of your program and can potentially be accessed from anywhere in your code, though doing so requires careful consideration of design principles. These are called global variables.

#include <iostream>

int globalCounter = 0; // Global variable

int main() {

int localValue = 10; // Local variable

std::cout << localValue << std::endl; // Works fine

std::cout << globalCounter << std::endl; // Works fine

return 0;

} // localValue is destroyed hereGlobal variables persist throughout your program’s execution and maintain their values between function calls. However, overusing global variables is generally considered poor practice because it makes programs harder to understand and maintain. Functions can modify global variables as a side effect, making it difficult to track what’s changing values and why. Local variables are preferred because they limit the scope of potential errors and make your code more modular and easier to reason about.

Constants represent values that should never change after initialization. You declare constants using the const keyword:

const double PI = 3.14159265359;

const int DAYS_IN_WEEK = 7;Attempting to modify a constant after declaring it produces a compiler error, which is exactly the point—constants prevent accidental modification of values that should remain fixed. By convention, constant names are often written in all capital letters to make them visually distinct from variables, though this is a style choice rather than a language requirement.

Modern C++ also provides constexpr, which indicates that a value can be computed at compile time:

constexpr int ARRAY_SIZE = 100;

constexpr double TAX_RATE = 0.0825;For simple constants, const and constexpr often work identically from a programmer’s perspective, though constexpr provides stronger guarantees to the compiler about when values are known, enabling certain optimizations. As a beginner, understanding that both create unchangeable values suffices—the subtle differences become relevant as you explore more advanced C++ features.

Type inference with the auto keyword, introduced in C++11, allows the compiler to automatically deduce the type of a variable from its initializer:

auto age = 25; // compiler deduces int

auto price = 19.99; // compiler deduces double

auto name = "Alice"; // compiler deduces const char*While auto can make code more concise, especially with complex template types, overusing it can make code harder to understand because readers can’t immediately see what type a variable has. For simple cases where the type is obvious from context, auto works well. For cases where the type isn’t immediately clear, explicitly writing the type makes your code more readable.

Understanding type conversion becomes important when mixing different types in expressions. C++ performs implicit conversions in many situations, automatically converting between compatible types. When you mix integers and floating-point numbers in calculations, integers are promoted to floating-point:

int whole = 5;

double fractional = 2.5;

double result = whole + fractional; // result is 7.5However, assigning a floating-point value to an integer variable truncates the decimal portion without warning:

double pi = 3.14159;

int truncated = pi; // truncated is 3, decimal portion lostThis silent data loss can cause bugs if you’re not aware it’s happening. Modern C++ provides explicit casting syntax for situations where you intentionally want to convert between types:

double pi = 3.14159;

int truncated = static_cast<int>(pi); // explicitly convert, makes intention clearUsing explicit casts documents your intention to convert types, making code more maintainable and helping other programmers (including your future self) understand that the conversion is deliberate rather than accidental.

Variable naming conventions significantly impact code readability. C++ doesn’t enforce specific naming styles, but following consistent conventions makes your code easier to understand. Variable names should be descriptive, indicating what the variable represents. Compare these examples:

int x; // What does x represent?

int studentCount; // Clearly indicates a count of studentsMost C++ code uses camelCase for variable names, where the first letter is lowercase and subsequent words begin with uppercase letters. Some projects use snake_case, where words are separated by underscores. Choose a convention and apply it consistently throughout your code.

Variable names must follow certain rules: they must begin with a letter or underscore, can contain letters, digits, and underscores, and cannot be C++ keywords (reserved words like int, return, class). Names are case-sensitive, meaning age, Age, and AGE are three different variables:

int age = 25;

int Age = 30; // Different variable than age

int AGE = 35; // Yet another different variableWhile legal, creating variables that differ only in capitalization invites confusion and errors. Choose distinct, meaningful names that make your code self-documenting.

The sizeof operator tells you how many bytes a type or variable occupies:

std::cout << sizeof(int) << std::endl; // typically prints 4

std::cout << sizeof(double) << std::endl; // typically prints 8

std::cout << sizeof(char) << std::endl; // always prints 1Understanding the size of types matters when you’re working with memory-constrained systems or need to understand performance characteristics. The C++ standard specifies minimum sizes for types but allows implementations to use larger sizes, which is why int might be four bytes on most systems but could theoretically be larger.

Overflow occurs when you try to store a value larger than a type can hold. For unsigned integers, values wrap around to zero. For signed integers, overflow causes undefined behavior—the C++ standard doesn’t specify what happens, and different compilers might handle it differently:

unsigned char value = 255;

value = value + 1; // wraps to 0

int maxInt = 2147483647; // maximum value for 32-bit int

maxInt = maxInt + 1; // undefined behavior - might wrap to negative, might notBeing aware of overflow helps you choose appropriate types for your data and understand potential bugs when calculations produce unexpected results.

Arithmetic operations with variables work as you’d expect, using standard mathematical operators:

int a = 10;

int b = 3;

int sum = a + b; // 13

int difference = a - b; // 7

int product = a * b; // 30

int quotient = a / b; // 3 (integer division truncates)

int remainder = a % b; // 1 (modulo operator gives remainder)Integer division truncates any fractional result—10 divided by 3 is 3, not 3.33. If you want floating-point division, at least one operand must be a floating-point type:

double result = 10.0 / 3; // 3.33333...The modulo operator (%) works only with integer types and gives you the remainder after division. It’s useful for many programming tasks, like determining if a number is even or odd, or implementing cyclic behavior.

Compound assignment operators combine an operation with assignment, providing a shorthand for modifying a variable based on its current value:

int count = 10;

count = count + 5; // add 5 to count

count += 5; // equivalent shorthandC++ provides compound assignment operators for all arithmetic operations: +=, -=, *=, /=, and %=. These operators don’t just save typing—they can be more efficient in complex expressions and clearly express the intent to modify a variable.

Increment and decrement operators provide an even more concise way to add or subtract one:

int value = 5;

value++; // increment, value is now 6

value--; // decrement, value is now 5These operators come in prefix (++value) and postfix (value++) forms. For simple statements like these, the forms work identically. The difference matters in more complex expressions where you use the value and modify it in the same statement, but understanding this subtle distinction can wait until you encounter situations where it matters.

Key Takeaways

Variables are named storage locations in memory that hold values your program manipulates. Every variable in C++ has a specific type that determines what kind of data it can store, how much memory it occupies, and what operations you can perform on it. Understanding fundamental types—integers (int), floating-point numbers (float, double), characters (char), booleans (bool), and strings (std::string)—equips you to store and work with virtually any kind of data your programs need.

Initializing variables when you declare them prevents bugs caused by reading undefined values. Choosing appropriate types for your data—integers for whole numbers, doubles for fractional values, strings for text—ensures your programs work correctly and efficiently. Following good naming conventions makes your code self-documenting and easier to maintain.

The concepts you’ve learned about variables and data types form the foundation for everything else in programming. Every program you write will use variables extensively, storing user input, tracking program state, performing calculations, and producing results. Mastering these fundamentals now makes learning more advanced concepts much easier because you’ll have solid understanding of how data is stored and manipulated in your programs.