Introduction

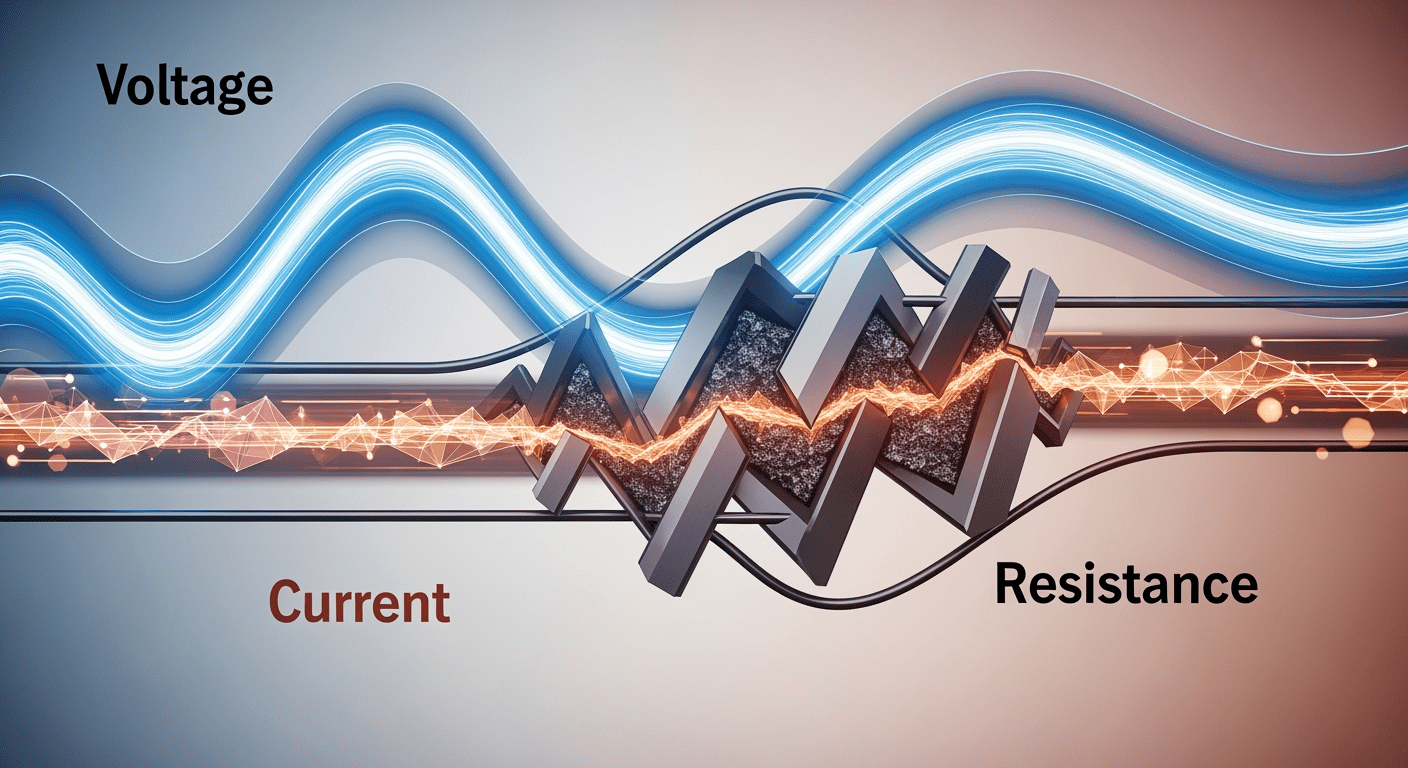

If electricity were a language, voltage, current, and resistance would be its three most essential words. These three quantities form the fundamental vocabulary of electronics, appearing in every circuit analysis, every component specification, and every troubleshooting session you will ever encounter. Yet despite their ubiquity and importance, these concepts often confuse beginners because they are invisible, abstract, and interconnected in ways that can seem counterintuitive at first.

Understanding the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance is not merely academic knowledge. It represents the key that unlocks your ability to design circuits, select appropriate components, diagnose problems, and predict how electrical systems will behave. Whether you want to build a simple LED flashlight or design sophisticated electronic instruments, you will use these three concepts constantly, making decisions based on how they interact and influence each other.

This comprehensive guide will build your understanding from the ground up, using multiple perspectives and analogies to ensure these abstract concepts become concrete and intuitive. We will explore what each quantity represents physically, how to measure it, how to visualize it, and most importantly, how voltage, current, and resistance work together to determine electrical behavior in real circuits.

Understanding Voltage: The Electrical Driving Force

Voltage stands as perhaps the most fundamental concept in electronics, yet it is also one of the most frequently misunderstood. To truly grasp what voltage represents, we need to approach it from several different angles, building up a complete mental model that goes beyond simple definitions.

The Physical Nature of Voltage

Voltage, formally known as electric potential difference, represents the amount of electrical potential energy difference between two points in a circuit. This definition, while technically accurate, does not immediately illuminate what voltage actually does or why it matters. A more intuitive understanding comes from recognizing that voltage is the force that motivates electrons to move through a conductor.

Imagine standing at the top of a hill holding a ball. The ball possesses potential energy by virtue of its elevated position. If you release the ball, this potential energy converts to kinetic energy as the ball rolls downhill. The steeper the hill, the more potential energy exists, and the faster the ball will accelerate. Voltage works similarly in electrical circuits. Electrons at the negative terminal of a battery possess electrical potential energy, just as the ball at the hilltop possesses gravitational potential energy. When we provide a path through a circuit, electrons “roll downhill” from high potential to low potential, converting their potential energy into other forms along the way.

The key insight here is that voltage always represents a difference between two points. Just as we can only measure the height of a hill relative to some reference point, we can only measure voltage as the potential difference between two locations in a circuit. A 9-volt battery does not contain nine volts in any absolute sense. Rather, it maintains a 9-volt difference between its positive and negative terminals, creating the electrical “hill” that drives electrons through connected circuits.

Voltage as Energy Per Charge

Another valuable perspective comes from understanding voltage in terms of energy. One volt is defined as one joule of energy per coulomb of charge. A coulomb represents the charge carried by approximately 6.24 billion billion electrons, an almost incomprehensibly large number that highlights just how tiny individual electrons are. When we say a battery provides 12 volts, we mean that every coulomb of charge that flows from the negative terminal to the positive terminal will release 12 joules of energy as it makes this journey.

This energy-per-charge perspective helps explain why higher voltages can be more dangerous. A 120-volt household outlet provides ten times more energy per coulomb than a 12-volt car battery. If the same amount of charge flows through your body in both cases, the higher voltage source delivers ten times more energy, which translates to ten times more potential for harm through heating tissue, disrupting nerve signals, or interfering with heart rhythms.

Voltage Sources and Maintenance

Different devices create and maintain voltage in different ways, and understanding these mechanisms provides insight into how voltage actually works. A battery creates voltage through chemical reactions that separate positive and negative charges, accumulating them at opposite terminals. These reactions work continuously to maintain the voltage difference even as current flows, at least until the chemical reactants are exhausted.

Generators create voltage through electromagnetic induction, physically moving conductors through magnetic fields to push electrons toward one end of the conductor and away from the other. Power supplies convert one form of voltage to another, perhaps transforming the 120-volt alternating current from a wall outlet into the 5-volt direct current your phone needs, using transformer principles and rectification circuits.

What all voltage sources have in common is their ability to maintain a potential difference between two points. A dead battery can no longer maintain its voltage because the chemical reactions that separate charges have reached equilibrium. A generator spinning too slowly cannot maintain proper voltage because the electromagnetic induction is insufficient. Understanding that voltage is actively maintained rather than simply existing helps explain why voltage sources have limits and why they can fail.

Measuring Voltage

When we measure voltage with a multimeter or oscilloscope, we are quantifying the potential difference between the two probe points. This measurement technique reveals an important practical consideration: voltage measurements are always made in parallel with the circuit element being measured. We place one probe at one end of the component and the other probe at the opposite end, measuring the potential difference across the component.

Voltmeters are designed with extremely high internal resistance, typically many millions of ohms. This design ensures that the meter itself draws negligible current from the circuit, preventing the measurement process from significantly affecting the voltage being measured. A perfect voltmeter would have infinite resistance, drawing zero current and having no impact on circuit operation. Real voltmeters approximate this ideal closely enough that their effect is usually negligible in most practical circuits.

Different voltage ranges require different measurement considerations. Measuring the 1.5 volts from an AA battery is straightforward and safe. Measuring the 120 volts from a wall outlet requires caution and proper equipment rated for these voltages. Measuring the thousands of volts inside a television’s cathode ray tube or a car’s ignition system requires specialized high-voltage probes and extreme care.

Understanding Current: The Flow of Charge

If voltage represents the push that drives electrons, current represents the actual flow of those electrons through a conductor. Current is perhaps the most intuitive of our three fundamental quantities because it directly corresponds to something moving, yet it too has subtleties that deserve careful exploration.

Defining Electrical Current

Current, measured in amperes or amps, quantifies the rate at which electrical charge flows past a given point in a circuit. One ampere represents one coulomb of charge flowing past a point per second. Since one coulomb contains approximately 6.24 billion billion electrons, one ampere means that this enormous number of electrons flows past any given point in the circuit every single second.

This definition reveals why even small currents involve staggering numbers of individual electrons. A typical LED might operate at 20 milliamps, which seems like a tiny current. Yet this still represents about 125 million billion electrons flowing through the LED every second. The sheer quantity of electrons involved in even modest currents highlights why we measure charge in coulombs rather than counting individual electrons.

Current as Coordinated Movement

It is crucial to understand that current does not mean electrons racing through wires at tremendous speeds. Individual electrons actually drift through conductors relatively slowly, typically at speeds measured in millimeters per second. What we call current results from a coordinated push throughout the entire circuit, somewhat like how water pressure travels through pipes at the speed of sound even though the water molecules themselves move much more slowly.

When you flip a light switch, the light turns on essentially instantaneously, even though electrons from the switch take considerable time to actually reach the bulb. This happens because the electromagnetic field propagates through the circuit at nearly the speed of light, creating a coordinated push throughout the conductor simultaneously. Electrons throughout the entire circuit start moving almost at once, not because individual electrons race from the switch to the bulb, but because the electrical field affects all the free electrons in the circuit simultaneously.

Conventional Current Versus Electron Flow

An important historical note affects how we talk about current direction. Early scientists studying electricity believed that current flowed from positive to negative, establishing what we now call conventional current direction. Later discoveries revealed that electrons, which carry negative charge, actually flow from negative to positive. This means conventional current and electron flow proceed in opposite directions.

Modern electronics uses conventional current almost universally when drawing circuit diagrams and analyzing circuits, even though we know electrons actually flow the opposite direction. This convention is so entrenched that changing it would create more confusion than clarity. Fortunately, circuit analysis works correctly using conventional current as long as we apply it consistently. When we say current flows from the positive terminal through a circuit to the negative terminal, we are describing conventional current. The actual electrons are flowing the opposite direction, but our analysis and calculations remain valid.

Current and Circuit Paths

Current exhibits a crucial property: the same current must flow through all components in a simple series circuit. This principle, sometimes called conservation of charge, means that charge cannot accumulate or disappear at any point in a continuous circuit. If one ampere flows out of the battery’s negative terminal, one ampere must flow through each component in sequence, and one ampere must return to the battery’s positive terminal.

This concept often surprises beginners who intuitively expect current to get “used up” as it flows through components, like water being consumed from a pipe. In reality, current represents flow rate, and the electrons that enter a component must exit it at the same rate they entered. What changes is the electrical potential energy of those electrons, which decreases as they flow through resistive elements, converting electrical energy to other forms like heat or light.

In parallel circuits, current divides among the available paths, with more current flowing through paths that offer less resistance. The total current flowing out of the power source equals the sum of currents through all parallel branches, once again conserving charge. No matter how complex the circuit becomes, the principle remains: charge is conserved, and current at any point represents the rate at which charge flows past that location.

Measuring Current

Unlike voltage, which we measure across components, we measure current through components. This requires breaking the circuit at the point of interest and inserting the ammeter in series with the circuit so that all the current we want to measure flows through the meter. This fundamental difference in measurement technique reflects the different natures of voltage and current.

Ammeters are designed with very low internal resistance, ideally approaching zero. This design ensures the ammeter does not significantly impede current flow or alter circuit behavior during measurement. A perfect ammeter would have exactly zero resistance, dropping no voltage as current flows through it. Real ammeters approximate this ideal closely enough for most purposes, though their small internal resistance becomes significant when measuring very small currents or in circuits where every millivolt matters.

Measuring current requires more care than measuring voltage because inserting an ammeter incorrectly can damage it or the circuit. Connecting an ammeter directly across a voltage source, as you would a voltmeter, creates a short circuit through the meter’s low resistance, potentially destroying the meter and creating a fire hazard. Modern multimeters include fuses in their current measurement circuitry to protect against exactly this mistake, which beginners make with unfortunate frequency.

Different current ranges require different approaches. Measuring milliamps in a low-power circuit is straightforward. Measuring hundreds of amps in automotive or industrial applications requires specialized clamp meters that measure the magnetic field created by current flow rather than actually breaking the circuit. These non-invasive measurement techniques become essential when currents are too large to safely interrupt or when breaking the circuit is impractical.

Understanding Resistance: Opposition to Flow

Resistance completes our fundamental trio, representing the property that opposes current flow. While voltage pushes and current flows, resistance restricts, creating the three-way interaction that determines all circuit behavior.

The Physical Basis of Resistance

Resistance arises from the interactions between moving electrons and the atomic structure of the conductor. Even in excellent conductors like copper, electrons do not flow completely freely. As they move through the material, they collide with atoms, transfer energy to the atomic lattice, and experience forces that impede their motion. These microscopic interactions manifest as macroscopic resistance.

Different materials resist current flow to vastly different degrees based on their atomic and molecular structure. Conductors like copper, silver, and aluminum have atomic structures that allow valence electrons to move relatively freely, resulting in low resistance. Insulators like rubber, glass, and plastic have structures that bind electrons tightly, creating resistance so high that essentially no current flows under normal voltages. Semiconductors fall between these extremes, with resistance that can be manipulated through doping and other techniques.

Even pure conductors exhibit some resistance. A copper wire might have very low resistance per meter, but a long enough length will accumulate significant total resistance. This is why power transmission lines use very thick conductors and why long extension cords cause noticeable voltage drops when powering high-current devices. The resistance is small, but the length makes it matter.

Factors Affecting Resistance

Several physical factors determine a conductor’s resistance, and understanding these factors helps explain many practical aspects of circuit design and troubleshooting. Material composition stands as the most fundamental factor. Silver has the lowest electrical resistance of all metals, followed closely by copper and gold. Aluminum offers higher resistance but much lower cost and weight, making it popular for power transmission despite requiring thicker conductors to match copper’s current capacity.

Length directly affects resistance: doubling the length of a wire doubles its resistance. This relationship is perfectly linear because current must traverse twice as many atomic obstacles in twice the distance. Every meter of wire adds its characteristic resistance per meter to the total, accumulating linearly with length.

Cross-sectional area has an inverse relationship with resistance. Doubling the cross-sectional area of a wire halves its resistance because current has twice as many parallel paths available through the conductor. This is why high-current applications use thick wires: the increased cross-sectional area reduces resistance proportionally, minimizing energy loss and heat generation.

Temperature significantly affects resistance in most materials. In typical conductors, resistance increases with temperature as increased atomic vibration creates more obstacles for electron flow. This temperature dependence creates a feedback effect: current through resistance generates heat, which increases resistance, which generates more heat. In extreme cases, this positive feedback can lead to thermal runaway and conductor failure.

Semiconductors often exhibit the opposite temperature behavior, with resistance decreasing as temperature increases. This happens because higher temperatures free more charge carriers from the atomic lattice, providing more electrons and holes to carry current. This inverse relationship makes thermistors, temperature-sensitive resistors, valuable for temperature measurement and compensation circuits.

Resistance as Energy Conversion

Resistance does more than simply impede current flow. It converts electrical energy into thermal energy, a process that underlies countless applications from toasters to light bulbs to electric heaters. When current flows through resistance, electrons collide with atoms, transferring kinetic energy that manifests as heat. The rate of this energy conversion depends on both the resistance and the current flowing through it, following a mathematical relationship we will explore shortly.

This energy conversion is sometimes desirable and sometimes problematic. In a heating element, we deliberately use resistance to convert electrical energy to heat. In a power supply, resistance in conductors represents parasitic loss that wastes energy and reduces efficiency. Understanding resistance helps us design circuits that exploit it when useful and minimize it when detrimental.

Measuring Resistance

We measure resistance in ohms, represented by the Greek letter omega (Ω). One ohm represents the resistance of a conductor that carries one ampere of current when one volt is applied across it. This definition directly connects resistance to the relationship between voltage and current, a connection that forms the basis of Ohm’s Law.

Measuring resistance requires removing the component from the circuit or ensuring no other voltage source is connected, because ohmmeters work by applying a known small voltage and measuring the resulting current to calculate resistance. Any external voltage source will interfere with this measurement, producing incorrect readings or potentially damaging the meter.

Unlike voltage and current, which vary continuously in active circuits, resistance is typically a fixed property of components. A given resistor has a specific resistance value that does not change significantly with the voltage applied or current flowing, at least within its designed operating range. This constancy makes resistance values fundamental specifications around which we design circuits.

The Fundamental Relationship: Ohm’s Law

The three quantities we have explored do not exist independently. They are bound together by one of the most important relationships in all of electronics, discovered by German physicist Georg Ohm in 1827 and now known universally as Ohm’s Law.

The Mathematical Expression

Ohm’s Law states that voltage equals current times resistance, expressed mathematically as V = I × R, where V represents voltage in volts, I represents current in amperes, and R represents resistance in ohms. This deceptively simple equation describes a profound relationship that governs behavior in the vast majority of electrical circuits.

We can rearrange this equation to solve for any of the three quantities when we know the other two. If we know current and resistance, we can calculate voltage: V = I × R. If we know voltage and resistance, we can calculate current: I = V ÷ R. If we know voltage and current, we can calculate resistance: R = V ÷ I. These three forms of Ohm’s Law provide the foundation for most circuit analysis.

Interpreting Ohm’s Law

The mathematical expression encodes several important insights about electrical behavior. First, it reveals that voltage and current are directly proportional when resistance remains constant. Double the voltage across a fixed resistance, and current doubles. Halve the voltage, and current halves. This linear relationship makes circuit behavior predictable and allows precise control through voltage adjustment.

Second, it shows that current and resistance have an inverse relationship when voltage remains constant. Double the resistance, and current halves. This makes intuitive sense: greater resistance restricts current flow, reducing the amount of charge that flows for any given voltage. Halve the resistance, and current doubles, as the reduced opposition allows more charge to flow.

Third, it demonstrates that achieving a specific current through a resistance requires a proportional voltage. Want to push more current through a given resistance? You must apply higher voltage. Want to limit current? Either reduce the applied voltage or increase the resistance.

Practical Applications of Ohm’s Law

Engineers and technicians use Ohm’s Law constantly in practical work. Selecting a current-limiting resistor for an LED requires Ohm’s Law: if the LED needs 20 milliamps and drops 2 volts, and your power supply provides 5 volts, you need to drop 3 volts across the resistor at 20 milliamps, giving R = V ÷ I = 3V ÷ 0.02A = 150 ohms.

Troubleshooting circuits relies heavily on Ohm’s Law. If you measure unexpected voltage across a component, you can calculate what current should be flowing and verify it with current measurement. Discrepancies between calculated and measured values reveal problems: higher-than-expected resistance suggests poor connections or degraded components, while lower resistance might indicate short circuits or parallel paths you did not account for.

Designing power supplies requires Ohm’s Law to calculate voltage drops in conductors and ensure regulation circuits maintain proper voltage under varying loads. Sizing wire for installations uses Ohm’s Law to calculate voltage drop based on wire resistance and expected current, ensuring adequate voltage reaches the load.

Limitations of Ohm’s Law

Despite its power and utility, Ohm’s Law has limitations that you must understand to avoid misapplication. It applies only to ohmic materials, conductors whose resistance remains constant regardless of the applied voltage or resulting current. Most resistors behave ohmically over their designed operating range, making Ohm’s Law broadly applicable for common circuit analysis.

However, many important electronic components do not obey Ohm’s Law. Diodes have resistance that varies dramatically with applied voltage direction and magnitude. Transistors have complex nonlinear relationships between voltage and current that cannot be captured by simple resistance. Light bulbs have resistance that changes with temperature, which changes with current, creating non-ohmic behavior. Batteries have internal resistance but also maintain voltage actively, making their behavior more complex than Ohm’s Law alone can describe.

Even ohmic resistors have limits. At very high currents, resistor temperature increases significantly, changing resistance and invalidating the assumption of constant resistance. At very high frequencies, capacitive and inductive effects become significant, adding reactive impedance that pure resistance does not capture.

Understanding these limitations prevents misapplication while maintaining appreciation for how broadly Ohm’s Law does apply. Within its domain of applicability, it remains one of the most useful tools in the electronics toolkit.

The Hydraulic Analogy Revisited

Throughout this article, we have referenced water flow as an analogy for electrical behavior. This hydraulic analogy, while imperfect, provides valuable intuition about the relationships between voltage, current, and resistance. Let us now examine this analogy in greater detail to solidify understanding.

Voltage as Water Pressure

Voltage corresponds to water pressure in a plumbing system. Higher pressure pushes water through pipes more forcefully, just as higher voltage pushes electrons through conductors more forcefully. A water pump that creates high pressure is analogous to a high-voltage battery or power supply. The pressure difference between two points in a water system corresponds to the voltage difference between two points in an electrical circuit.

Just as water only flows when pressure differs between two points, current only flows when voltage differs between two points. Connecting two points at identical pressure produces no water flow. Connecting two points at identical voltage produces no current flow. The pressure gradient drives water movement; the voltage gradient drives electron movement.

Current as Flow Rate

Current corresponds to the volumetric flow rate of water, measured in gallons per minute or liters per second. More water flowing per unit time represents higher flow rate, just as more charge flowing per unit time represents higher current. A trickle from a faucet represents low flow rate; a fire hose represents high flow rate. Similarly, a small LED drawing 20 milliamps represents low current; a space heater drawing 10 amps represents high current.

The analogy extends to conservation principles. Water flowing into a pipe junction must equal water flowing out, barring leaks. Similarly, current flowing into a circuit junction must equal current flowing out, barring unusual situations. Both systems conserve their flowing quantity.

Resistance as Pipe Restrictions

Resistance corresponds to friction and restrictions in pipes. A narrow pipe restricts water flow more than a wide pipe, just as a thin wire restricts current flow more than a thick wire. Rough pipe interiors create more friction than smooth interiors, analogous to how different materials have different resistivities. A partially closed valve adds resistance to water flow, similar to how a resistor adds resistance to current flow.

The inverse relationship between resistance and flow holds in both systems. Given constant pressure, increasing pipe restriction decreases flow rate. Given constant voltage, increasing resistance decreases current. Given constant flow rate, increasing restriction requires higher pressure to maintain that flow. Given constant current, increasing resistance requires higher voltage to maintain that current.

Limitations of the Hydraulic Analogy

While useful, the hydraulic analogy has limits. Water has mass and inertia; electrons have negligible mass and respond essentially instantaneously to electric fields. Water compresses minimally; the electromagnetic effects in circuits propagate at nearly the speed of light. Water systems can store energy through elevated reservoirs; electrical systems store energy in fundamentally different ways through capacitors and inductors.

The analogy also breaks down for alternating current, where the flow direction reverses periodically. While we can imagine water sloshing back and forth in pipes, this does not occur in normal plumbing and strains the analogy’s usefulness. Capacitors and inductors, crucial components in AC circuits, have no simple hydraulic equivalents.

Despite these limitations, the hydraulic analogy provides valuable intuition when used appropriately. It helps beginners develop mental models of invisible electrical phenomena by connecting them to visible, tangible water behavior. As understanding deepens, you will naturally move beyond the analogy to more sophisticated mental models, but initially, it serves an important pedagogical function.

Power: The Consequence of Voltage, Current, and Resistance

Understanding voltage, current, and resistance enables us to understand electrical power, the rate at which electrical energy is consumed or converted. Power brings together all three fundamental quantities in relationships that govern circuit design and operation.

Defining Electrical Power

Electrical power, measured in watts, represents the rate of energy transfer or conversion. One watt equals one joule per second, quantifying how quickly electrical energy is being transformed into other forms. A 60-watt light bulb converts 60 joules of electrical energy into light and heat every second. A 1500-watt hair dryer converts 1500 joules per second, explaining why it produces so much more heat than the bulb.

Power relates to voltage and current through the equation P = V × I, where P represents power in watts, V represents voltage in volts, and I represents current in amperes. This relationship reveals that power depends on both how hard we push electrons (voltage) and how many electrons we move per second (current). High power requires either high voltage, or high current, or both.

Power Equations Using Resistance

We can combine the power equation with Ohm’s Law to derive alternative expressions for power that use resistance. Starting with P = V × I and substituting I = V ÷ R gives us P = V × (V ÷ R) = V² ÷ R. This form calculates power when we know voltage and resistance.

Alternatively, substituting V = I × R into P = V × I gives us P = (I × R) × I = I² × R. This form calculates power when we know current and resistance.

These three equations, P = V × I, P = V² ÷ R, and P = I² × R, all describe the same physical phenomenon but suit different calculation scenarios. When designing circuits, you will choose whichever form uses the quantities you know or can most easily measure.

Power Dissipation and Component Ratings

Resistance converts electrical energy to heat through power dissipation, a process that can damage components if power exceeds their ratings. Every resistor, every semiconductor, and every other component has a maximum power rating that must not be exceeded during normal operation. Exceeding this rating causes excessive temperature rise that can destroy the component or reduce its lifespan.

Common resistor power ratings include 1/8 watt, 1/4 watt, 1/2 watt, and 1 watt, with higher power resistors available for demanding applications. Physical size generally correlates with power rating because larger components can dissipate heat more effectively. If your calculation shows a resistor dissipating 0.3 watts, a 1/4-watt resistor would overheat, potentially burning or changing value. You need at least a 1/2-watt resistor, though a 1-watt resistor provides a safer margin.

These power calculations are not optional or merely theoretical. They directly determine whether your circuit will function reliably or fail, sometimes catastrophically. Calculating power dissipation in every component and ensuring adequate power ratings represents a non-negotiable requirement of competent circuit design.

Practical Examples and Calculations

Abstract understanding becomes concrete through specific examples. Let us work through several scenarios that demonstrate how voltage, current, and resistance interact in real circuits.

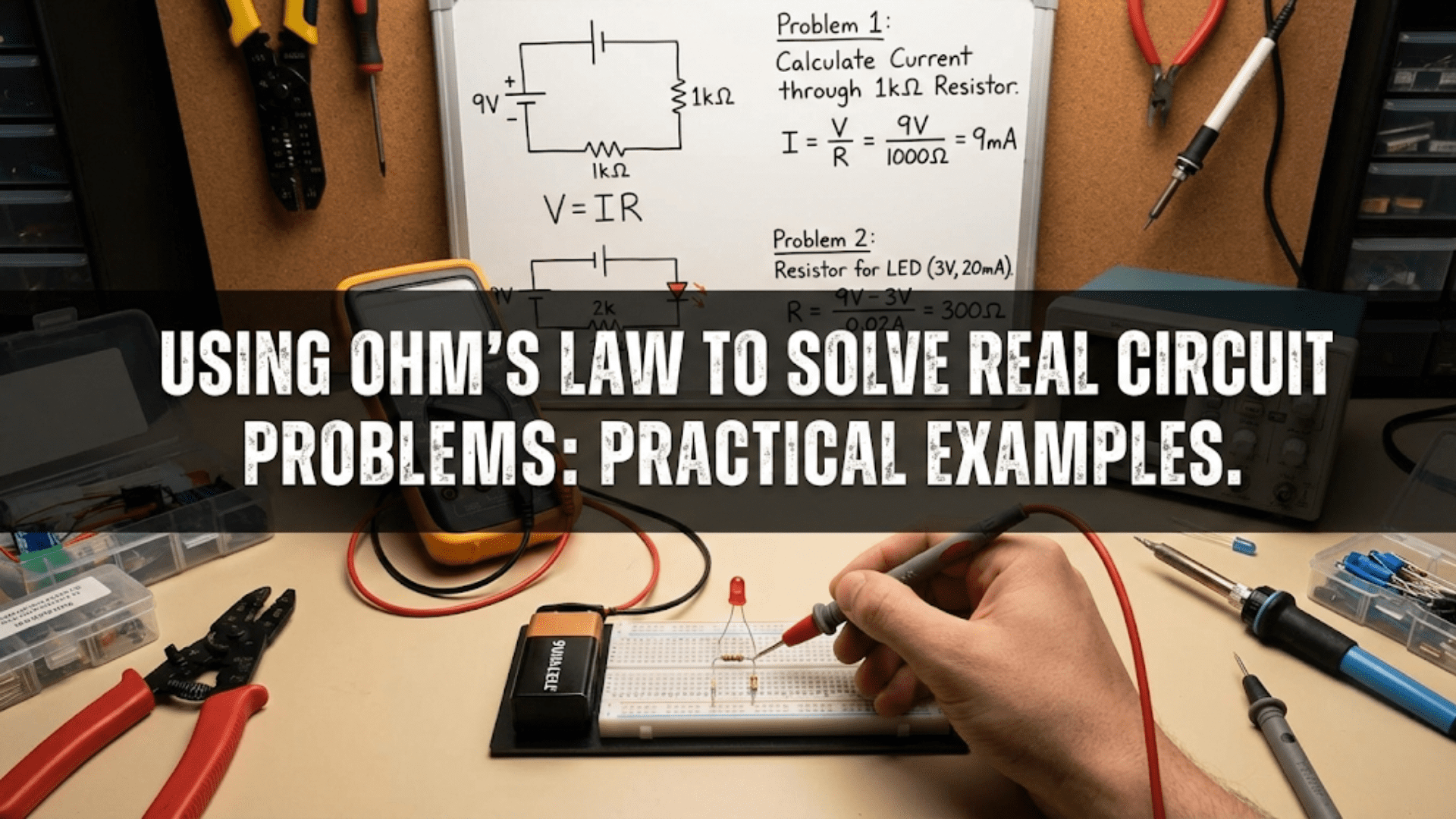

Example 1: LED Current-Limiting Resistor

You want to power a red LED from a 9-volt battery. The LED specifications indicate it needs 20 milliamps of current and drops 2 volts when conducting. What resistance value do you need?

First, we recognize that the LED drops 2 volts, leaving 9V – 2V = 7 volts that must drop across the resistor. We want 20 milliamps (0.020 amps) to flow through the circuit. Using Ohm’s Law: R = V ÷ I = 7V ÷ 0.020A = 350 ohms.

We would select a standard 330-ohm or 360-ohm resistor since 350 ohms is not a common value. The 330-ohm resistor would allow slightly more current; the 360-ohm resistor would allow slightly less. Either works acceptably.

For power rating, we calculate P = I² × R = (0.020A)² × 350Ω = 0.14 watts. A 1/4-watt resistor (0.25 watts) provides adequate rating with a reasonable safety margin.

Example 2: Voltage Drop in Wire

You are running 20 feet of 18-gauge copper wire to power a 12-volt, 5-amp device. The wire has 6.4 ohms resistance per 1000 feet. What voltage actually reaches the device?

First, calculate total wire resistance. We have 20 feet of wire each way (40 feet total), which gives us 40 ÷ 1000 × 6.4 = 0.256 ohms. Using Ohm’s Law with the 5-amp current: V = I × R = 5A × 0.256Ω = 1.28 volts dropped in the wire.

The device receives 12V – 1.28V = 10.72 volts, a voltage drop of over 10%. This might cause the device to malfunction if it requires close to 12 volts. Using thicker 16-gauge wire with lower resistance would reduce this voltage drop.

This example demonstrates why wire sizing matters in practical installations and why long cable runs require thicker conductors.

Example 3: Heating Element Design

You need to design a heating element that produces 1000 watts of heat from a 120-volt power source. What resistance and current are required?

Using P = V² ÷ R, we solve for R: R = V² ÷ P = (120V)² ÷ 1000W = 14,400 ÷ 1000 = 14.4 ohms.

Using P = V × I, we solve for current: I = P ÷ V = 1000W ÷ 120V = 8.33 amps.

We can verify these values are consistent using Ohm’s Law: V = I × R = 8.33A × 14.4Ω = 120V. The calculations confirm each other, increasing confidence in the design.

This heating element would draw over 8 amps, requiring appropriately sized wire and circuit breaker protection. The high power dissipation necessitates a heating element designed specifically for power handling, not an ordinary resistor.

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

Several persistent misconceptions about voltage, current, and resistance deserve explicit correction, as they frequently confuse beginners and lead to errors in circuit design and analysis.

Misconception 1: Current Gets Used Up

Many beginners believe current decreases as it flows through circuit components, getting “used up” like fuel being consumed. In reality, the same current flows through all components in a series circuit. What decreases is voltage, as electrical potential energy converts to other forms. The charge flow rate remains constant throughout the series path.

This misconception likely stems from conflating current (flow rate) with energy (the quantity being consumed). Energy is indeed consumed as current flows through resistive elements, but the current itself, the rate of charge flow, remains constant in a series circuit.

Misconception 2: Voltage Flows

Voltage does not flow. Current flows. Voltage represents potential difference, the electrical pressure that drives current flow. Saying “voltage flows through a circuit” is like saying “pressure flows through a pipe.” Pressure exists between points and drives flow; it does not itself flow. Voltage exists between points and drives current; it does not itself flow.

This linguistic confusion matters because it reveals and reinforces conceptual misunderstanding. Careful use of terminology helps develop and maintain clear mental models.

Misconception 3: Resistance Consumes Current

Resistance does not consume current. Resistance opposes current flow, limiting the amount of current that flows for a given voltage. In a series circuit, the same current flows through all resistances regardless of their values. Larger resistances do not consume more current; they simply require larger voltages to pass the same current.

Resistance does consume power, converting electrical energy to heat as current flows through it. This power consumption is real and important, but it differs from consuming current itself.

Misconception 4: Higher Resistance Means Higher Power

While P = I² × R suggests that higher resistance produces higher power dissipation, this equation only applies when current remains constant. In real circuits where voltage is fixed, increasing resistance actually decreases current (by Ohm’s Law), which decreases power dissipation (since power depends on current squared).

The complete relationship shows that for a fixed voltage, power dissipation is P = V² ÷ R, revealing that power decreases as resistance increases. Lower resistance draws more current and dissipates more power when connected to a fixed voltage source.

Context determines which relationship applies. In applications where current is actively regulated to remain constant, higher resistance does increase power dissipation. In typical circuits powered by voltage sources, higher resistance decreases power dissipation.

Advanced Considerations

As your understanding deepens, several advanced topics build on these fundamental concepts, extending them into more sophisticated domains of electronics.

Impedance: Beyond Simple Resistance

In alternating current circuits, the concept of resistance extends to impedance, which includes both resistive and reactive components. Capacitors and inductors oppose current flow in frequency-dependent ways that pure resistance cannot capture. Impedance, measured in ohms like resistance, provides a more complete description of opposition to current flow in AC circuits.

The mathematics becomes more complex, requiring complex numbers to properly represent magnitude and phase relationships. However, the fundamental principle remains: impedance plays the same role in AC circuits that resistance plays in DC circuits, determining how much current flows for a given voltage.

Nonlinear Elements

Many important circuit elements exhibit nonlinear relationships between voltage and current. Diodes conduct current readily in one direction while blocking it in the other. Transistors have complex transfer characteristics where small changes in control voltage or current produce large changes in output current. These nonlinear behaviors enable amplification, switching, and signal processing that purely resistive circuits cannot achieve.

Analyzing circuits with nonlinear elements requires techniques beyond simple Ohm’s Law application. Load line analysis, small-signal models, and iterative numerical methods become necessary tools. Yet understanding voltage, current, and resistance remains foundational even for these advanced techniques.

Dynamic Behavior

Our discussion has focused on steady-state conditions where values remain constant. Real circuits exhibit dynamic behavior when conditions change. Capacitors and inductors introduce time-dependent effects, causing voltages and currents to vary over time in response to changes in circuit conditions.

These dynamic effects are crucial for understanding filter circuits, oscillators, switching power supplies, and countless other applications. The mathematics involves differential equations rather than simple algebra, but voltage, current, and resistance remain the fundamental quantities whose relationships we analyze.

Conclusion: The Foundation of Circuit Understanding

Voltage, current, and resistance form an inseparable trio of concepts that define electrical behavior. Voltage provides the driving force, the electrical pressure that motivates charge to move. Current represents the flow itself, the movement of charge through conductors. Resistance opposes this flow, limiting current and converting electrical energy to heat in the process.

These three quantities are bound together by Ohm’s Law, a relationship so fundamental that you will use it constantly throughout your electronics journey. Whether calculating component values, troubleshooting circuit problems, designing power supplies, or analyzing complex systems, the relationship V = I × R will appear again and again.

Understanding these concepts deeply, not just memorizing formulas but developing genuine intuition for how voltage, current, and resistance interact, transforms electronics from an opaque mystery into a comprehensible system. You begin to see circuits not as random collections of components but as carefully orchestrated interactions between voltages that drive, currents that flow, and resistances that oppose and convert energy.

This understanding extends far beyond basic circuits. Even when working with complex integrated circuits containing billions of transistors, the fundamental relationships between voltage, current, and resistance remain operative at every level. Semiconductor physics, digital logic, analog signal processing, and power electronics all build upon these foundational concepts.

As you continue your electronics education, you will encounter these three quantities in endless variations and combinations. Each new component, each new circuit topology, and each new analysis technique will reveal new aspects of how voltage, current, and resistance interact. Yet the fundamentals remain constant, providing an anchor point from which all more advanced knowledge extends.

Master voltage, current, and resistance, and you have mastered the vocabulary of electronics. The language of circuits becomes readable, and the seemingly infinite variety of electronic systems resolves into variations on familiar fundamental themes. This foundation will serve you whether you pursue electronics as a hobby, a career, or simply seek to understand the technology that increasingly pervades modern life.