The story of artificial intelligence is one of the most fascinating journeys in human innovation. It’s a tale filled with brilliant insights, crushing disappointments, unexpected breakthroughs, and renewed hope. Understanding this history isn’t just about learning dates and names, it’s about seeing how ideas evolved, how failures led to new approaches, and how the AI systems we use today stand on the shoulders of decades of pioneering work.

In this article, we’ll travel through time, from the earliest philosophical questions about thinking machines to the powerful AI systems that are transforming our world today. Along the way, you’ll discover why AI research nearly died out multiple times, what brought it back to life, and how seemingly unrelated discoveries came together to create the AI revolution we’re experiencing now.

The Philosophical Foundations: Can Machines Think?

Long before computers existed, humans pondered whether machines could think. These weren’t idle philosophical musings, they laid the conceptual groundwork for artificial intelligence as we know it today.

In the 17th century, philosopher and mathematician René Descartes wondered whether animals were essentially biological machines operating according to mechanical principles. If complex behaviors could emerge from mechanical processes in animals, could they also emerge from artificial mechanisms? This question planted seeds that would germinate centuries later.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, another 17th-century philosopher and mathematician, dreamed of a universal logical language and a machine that could perform logical reasoning. He believed that arguments and disputes could be resolved through calculation rather than debate. While his vision wasn’t realized in his lifetime, he articulated ideas that would eventually become central to AI: the notion that reasoning itself might be mechanizable.

The 19th century brought Charles Babbage’s designs for mechanical computing devices, including his Analytical Engine. Though never completed during his lifetime, this machine incorporated key concepts of modern computing: the ability to be programmed, memory to store information, and the capacity to perform complex calculations. Ada Lovelace, often considered the first computer programmer, recognized something profound about Babbage’s machine: it could manipulate symbols according to rules, and those symbols could represent more than just numbers. This insight hinted at the possibility of machines doing more than arithmetic, they might process any information that could be symbolically represented.

These early thinkers established crucial ideas: that thinking might be a mechanical process, that complex behaviors could emerge from simple rules, and that machines might manipulate symbols in meaningful ways. They set the stage for the birth of AI as a formal field of study.

Alan Turing and the Birth of Computing Intelligence

The modern story of artificial intelligence truly begins with Alan Turing, a British mathematician whose work during World War II helped crack Nazi encryption codes and whose theoretical insights laid the foundations for computer science itself.

In 1936, before electronic computers even existed, Turing published a paper describing what we now call the Turing machine, an abstract mathematical model of computation. This theoretical device could perform any calculation that could be performed by any computer, no matter how sophisticated. Turing proved that certain problems were fundamentally unsolvable by any computational process, but more importantly for AI, he demonstrated that a single, universal machine could simulate any other computational process. This meant that, in principle, one machine could perform any task that could be precisely specified as a series of logical steps.

After the war, as electronic computers began to emerge, Turing turned his attention to a provocative question: “Can machines think?” In his groundbreaking 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” he proposed what became known as the Turing Test. Rather than trying to define thinking itself—a philosophically thorny problem—Turing suggested a practical test. If a machine could engage in a conversation that was indistinguishable from a human’s conversation, wouldn’t we have to admit it was thinking, or at least doing something equivalent to thinking?

The Turing Test captured imaginations and sparked debates that continue today. Critics argued it focused too much on imitation rather than genuine intelligence, but it gave researchers a concrete goal to pursue and forced them to think about what intelligence really meant.

Turing’s work established the theoretical possibility of thinking machines. The question was no longer whether machines could think in principle, but how to make them do so in practice.

The Birth of AI as a Field: The Dartmouth Conference

The summer of 1956 marked a turning point in history. At Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, a group of researchers gathered for a workshop that would give birth to artificial intelligence as a formal field of study. John McCarthy, who organized the conference, coined the term “artificial intelligence” for the proposal, choosing words that would capture the ambitious goal of creating machines with human-like intelligence.

The Dartmouth conference brought together brilliant minds who would shape AI for decades to come. John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Claude Shannon, and Nathaniel Rochester led the event, joined by other researchers who would become pioneers in the field. Their proposal was audacious: they believed that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.”

This bold optimism characterized the early years of AI. Researchers believed that machine intelligence was just around the corner—perhaps only a decade or two away. They had good reasons for optimism. Computers could now perform millions of calculations per second, far exceeding human capabilities in arithmetic. Surely extending this computational power to other forms of reasoning would be straightforward.

The Dartmouth attendees and their contemporaries quickly achieved results that seemed to validate their confidence. They created programs that could prove mathematical theorems, play checkers at a competitive level, and solve algebra problems. These early successes suggested that human-level AI might indeed be achievable in the near future.

The Golden Years: Early Successes and Grand Ambitions

The late 1950s and 1960s were heady times for AI research. Each new program seemed to demonstrate that machines could master tasks previously thought to require human intelligence.

In 1959, Arthur Samuel created a checkers program that learned from experience, improving its play over time. Remarkably, it eventually played better than Samuel himself. This demonstrated a crucial principle: machines could potentially exceed their creators’ abilities through learning, not just through brute-force calculation.

The Logic Theorist, created by Allen Newell and Herbert Simon, could prove mathematical theorems from symbolic logic. In some cases, it found proofs more elegant than those discovered by humans. This seemed to show that machines could engage in high-level reasoning and even creativity.

ELIZA, developed by Joseph Weizenbaum in 1964, could engage in remarkably human-like conversations by pattern-matching and substitution. Though Weizenbaum intended it partly as a demonstration of how superficial such conversations actually were, many users formed emotional attachments to the program and believed it understood them. This revealed both the potential and the pitfalls of conversational AI.

Researchers tackled increasingly ambitious problems. They worked on natural language understanding, computer vision, robotics, and expert systems designed to capture human expertise in specific domains. Government funding, particularly from the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), flowed freely into AI research.

However, a problem was emerging. These early AI systems worked well on carefully constructed problems in controlled environments but struggled when faced with the complexity and ambiguity of the real world. A program that could prove mathematical theorems couldn’t understand a simple children’s story. A robot that could stack blocks in a laboratory couldn’t navigate a normal room filled with everyday objects.

The First AI Winter: Reality Checks and Broken Promises

By the early 1970s, the initial optimism surrounding AI had begun to crumble under the weight of unfulfilled promises. The grand predictions made in the 1950s and 1960s hadn’t materialized. Human-level AI remained elusive, and many of the practical applications researchers had promised failed to deliver.

The problems ran deeper than researchers had anticipated. They discovered that intelligence wasn’t just about logical reasoning or following rules. It required vast amounts of knowledge about the world, common sense that humans took for granted, and the ability to handle uncertainty and ambiguity. Computers could calculate faster than humans, but they lacked the contextual understanding that even young children possessed naturally.

In 1973, the British government commissioned mathematician James Lighthill to review AI research. His report was damning. He concluded that AI research had failed to achieve its ambitious goals and that many of the problems were more difficult than researchers had imagined. The report led to dramatic cuts in AI funding in the United Kingdom.

Similar reassessments occurred worldwide. In 1974, the U.S. government sharply reduced funding for AI research. The field entered what became known as the “AI Winter”—a period of diminished funding, reduced interest, and general pessimism about AI’s prospects. Many researchers left the field entirely, and AI became almost a taboo term in some circles.

The first AI winter taught crucial lessons. Intelligence couldn’t be reduced to logical rules alone. Computers needed not just processing power but also ways to represent knowledge, handle uncertainty, and learn from experience. The problems were far more complex than early researchers had imagined.

Yet even during this difficult period, important work continued. Some researchers persisted, developing new approaches and gradually building the foundation for AI’s eventual resurgence.

Expert Systems and the Second Wave: Knowledge Is Power

The 1980s brought renewed interest in AI through a different approach. Rather than trying to create general intelligence, researchers focused on capturing human expertise in narrow domains through what became known as expert systems.

The idea was elegantly simple: if you could encode the knowledge of human experts into a computer system through a set of rules, that system could make decisions and recommendations in that specific domain. MYCIN, developed at Stanford in the 1970s but influential in the 1980s, diagnosed bacterial infections and recommended antibiotics. DENDRAL helped chemists identify molecular structures. XCON helped configure computer systems for customers.

These expert systems achieved genuine commercial success. Companies saw them as ways to preserve the expertise of retiring employees, make specialized knowledge more widely accessible, and ensure consistent decision-making. A new industry emerged around building and deploying expert systems. The Japanese government launched the “Fifth Generation Computer Systems” project in 1982, aiming to build massively parallel computers designed for AI applications, which spurred competitive responses from other countries.

However, expert systems had fundamental limitations. They were brittle—they worked well within their narrow domains but couldn’t handle situations outside those boundaries. They couldn’t learn from experience; updating them required painstaking manual work by human experts. The knowledge had to be laboriously encoded as explicit rules, a process that was time-consuming, expensive, and often incomplete.

Moreover, much human expertise turned out to be tacit—experts often couldn’t articulate exactly how they made decisions. They relied on intuition developed over years of experience, pattern recognition that happened below conscious awareness, and contextual understanding that was difficult to reduce to explicit rules.

By the late 1980s, the limitations of expert systems became apparent. The market for specialized AI hardware collapsed as general-purpose computers became more powerful. Once again, AI had promised more than it could deliver. The field entered a second AI winter in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with reduced funding and declining interest.

The Machine Learning Revolution: A New Paradigm

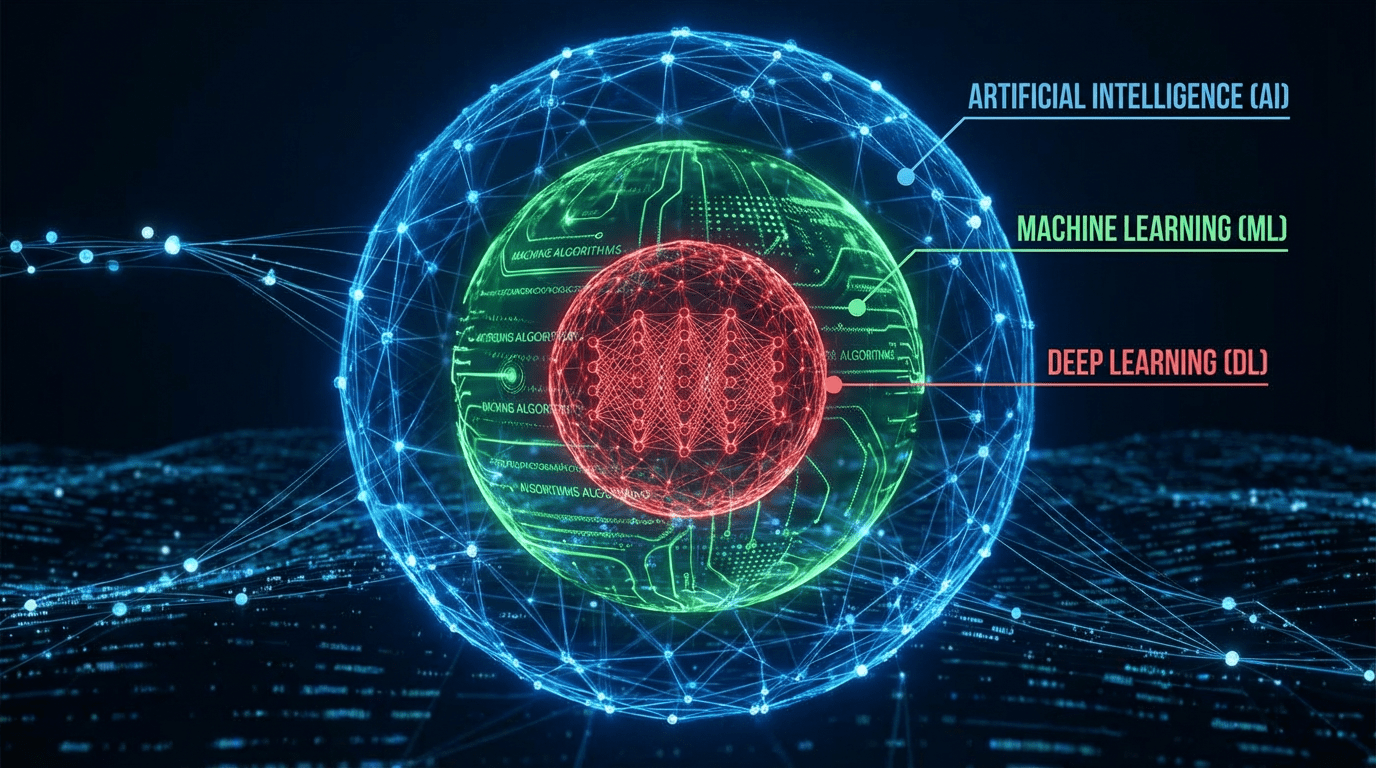

While expert systems rose and fell, a different approach to AI was quietly gaining ground. Rather than trying to program knowledge explicitly, what if machines could learn from data? This idea—machine learning—would eventually transform AI and bring about the renaissance we’re experiencing today.

Machine learning wasn’t entirely new. Researchers had explored learning systems since the earliest days of AI. But several developments in the 1980s and 1990s made it increasingly practical and powerful.

One crucial development was the rediscovery and improvement of neural networks. These systems, loosely inspired by the brain’s structure, could learn to recognize patterns through exposure to examples. In 1986, David Rumelhart, Geoffrey Hinton, and Ronald Williams popularized backpropagation, an algorithm that made it possible to train neural networks with multiple layers effectively. This overcame a major limitation of earlier neural network approaches.

Another important advance was the development of support vector machines and other sophisticated learning algorithms that could find complex patterns in data. These methods came with solid mathematical foundations and proved effective across many applications.

The increasing availability of data and computing power made machine learning more practical. As computers became faster and cheaper, it became feasible to train learning systems on larger datasets. The internet, in particular, would prove to be an enormous source of training data for AI systems.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, machine learning began achieving practical successes that caught public attention. IBM’s Deep Blue defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, demonstrating that computers could master complex strategic thinking. Speech recognition systems began working well enough for practical use. Spam filters learned to identify unwanted emails. Recommendation systems helped people find products and content they’d enjoy.

These weren’t just impressive demonstrations—they were systems that provided real value to millions of users. The focus had shifted from trying to replicate general human intelligence to building systems that could learn specific tasks from data. This more pragmatic approach proved far more successful than earlier attempts at creating general intelligence.

The Deep Learning Breakthrough: Bigger, Deeper, More Data

The next major turning point came in the early 2010s with the explosive success of deep learning—neural networks with many layers that could learn hierarchical representations of data.

Deep learning wasn’t fundamentally new. Neural networks had been around for decades, and the basic algorithms used in deep learning had been known since the 1980s. What changed was the convergence of three factors: much larger datasets, much more powerful computers (particularly graphics processing units originally designed for video games), and improved techniques for training deep networks.

The breakthrough moment came in 2012 when a deep learning system called AlexNet, created by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton, dramatically outperformed all previous approaches in the ImageNet image recognition competition. This wasn’t a modest improvement—it reduced the error rate by nearly half compared to the previous year’s winner. The AI community took notice.

Suddenly, deep learning was achieving results that had seemed impossible just years earlier. Systems could recognize objects in images with near-human accuracy. They could transcribe speech reliably in noisy environments. They could translate between languages with increasing fluency. They could beat human champions at the ancient game of Go, which was thought to be far beyond computer capabilities due to its enormous complexity.

Deep learning succeeded where earlier approaches had struggled because it could automatically learn useful features from raw data. Previous systems required human engineers to manually design the features the system would use—deciding which aspects of an image or sound wave to pay attention to. Deep learning systems learned these features automatically, often discovering patterns that humans hadn’t explicitly thought about.

The practical impact was enormous. Smartphones gained impressive capabilities in voice recognition and image classification. Self-driving cars began navigating real roads. Medical imaging systems helped doctors identify diseases. Translation services broke down language barriers. Virtual assistants became genuinely useful rather than novelties.

Companies raced to incorporate deep learning into their products and services. Tech giants like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon hired leading AI researchers and invested billions in AI research and development. Startups built entirely around AI capabilities emerged and often achieved remarkable valuations.

The Transformer Revolution: Attention Changes Everything

Just as the AI community was digesting the implications of deep learning’s success, another breakthrough emerged that would prove equally transformative.

In 2017, researchers at Google published a paper titled “Attention Is All You Need,” introducing the Transformer architecture. This new approach to neural networks relied on a mechanism called attention, which allowed the network to focus on different parts of the input when processing each element. While the paper initially addressed machine translation, the Transformer architecture would prove far more versatile and powerful than anyone initially anticipated.

Transformers addressed a key limitation of previous approaches to processing sequential data like text. Earlier methods processed sequences one element at a time, which made them slow and gave them difficulty capturing long-range relationships. Transformers could process entire sequences in parallel and easily capture relationships between distant elements.

Building on the Transformer architecture, researchers began developing what we now call large language models. These systems were trained on enormous amounts of text from the internet, learning patterns in language at unprecedented scale.

In 2018, Google introduced BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), which achieved remarkable results across many language understanding tasks. Later that year, OpenAI released GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), demonstrating impressive text generation capabilities.

These models kept getting larger and more capable. GPT-2, released in 2019, could generate remarkably coherent and contextually appropriate text. GPT-3, released in 2020 with 175 billion parameters, demonstrated abilities that shocked even AI researchers. It could perform a wide variety of language tasks with minimal or no task-specific training, simply by being shown a few examples or given instructions in natural language.

The implications extended beyond just language. Researchers discovered that the same Transformer architecture worked brilliantly for images, leading to Vision Transformers. Multi-modal systems like CLIP learned to connect language and images, understanding both text and visual information in a unified way.

By the early 2020s, Transformers had become the dominant architecture in AI, powering everything from language translation to code generation, from image creation to scientific discovery. They represented not just an incremental improvement but a fundamental shift in how AI systems were built and what they could do.

The Modern Era: AI Everywhere

Today, we live in an era where AI has become deeply embedded in our daily lives, often in ways we don’t even notice. The journey from Turing’s theoretical musings to today’s powerful AI systems took nearly 75 years, with many detours, setbacks, and unexpected breakthroughs along the way.

Modern AI systems can engage in remarkably natural conversations, generate creative content, analyze medical images, drive vehicles, play complex strategic games at superhuman levels, and assist in scientific research. Systems like ChatGPT, released in late 2022, brought sophisticated AI capabilities directly to hundreds of millions of users, fundamentally changing how people interact with technology.

Image generation systems like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion can create stunning visual art from text descriptions. AI assistants help programmers write code, writers draft documents, and students understand complex concepts. In scientific laboratories, AI helps discover new drugs, predict protein structures, and analyze astronomical data.

Yet for all these advances, we still don’t have anything approaching human-level general intelligence. Modern AI systems are remarkably capable within their training domains but lack the flexible, general-purpose intelligence that humans possess. They don’t truly understand the content they process in the way humans do. They can make surprising mistakes that reveal fundamental differences from human cognition.

The field also grapples with important challenges. AI systems can perpetuate or amplify biases present in their training data. They require enormous computational resources, raising concerns about environmental impact and accessibility. Questions about transparency, accountability, and the societal impact of AI grow more pressing as these systems become more powerful and widely deployed.

Lessons from History: Patterns in Progress

Looking back over AI’s history, several patterns emerge that offer insights into both past progress and future possibilities.

First, progress in AI has rarely been linear. The field has experienced cycles of excitement and disappointment, generous funding and scarcity, bold predictions and humbling setbacks. Each AI winter was triggered by overpromising and underdelivering, yet each led to valuable lessons that informed subsequent advances.

Second, breakthroughs often came not from entirely new ideas but from the convergence of existing concepts with increased computational power and data availability. Neural networks existed for decades before deep learning took off. The key ingredients were larger datasets, more powerful computers, and refinements in training techniques.

Third, successful AI applications have generally been narrow rather than general. Rather than creating human-like general intelligence, the field has made progress by focusing on specific tasks and domains. Even today’s most impressive AI systems are specialized tools rather than generally intelligent agents.

Fourth, the importance of data has been consistently underestimated. Early AI researchers focused on algorithms and reasoning, but modern successes rely heavily on learning from massive amounts of data. The companies with access to the most data have often led AI progress.

Fifth, philosophical questions about intelligence, understanding, and consciousness remain unresolved despite tremendous practical progress. We can build systems that perform intelligent tasks without fully understanding what intelligence is or whether machines truly understand what they’re doing.

Looking Forward: What History Tells Us About AI’s Future

The history of AI doesn’t provide a crystal ball, but it does offer perspective on what might come next and what challenges lie ahead.

We’re likely still in the relatively early stages of the current AI wave. Each previous breakthrough opened up years or even decades of incremental improvements and practical applications. The Transformer architecture and large language models are still being refined and extended, suggesting continued progress in the near term.

However, history also suggests caution about predicting timelines for major breakthroughs. The early pioneers thought general AI was perhaps a decade away. They were off by more than half a century and counting. Today’s researchers are more circumspect, but we still don’t know how far we are from truly general artificial intelligence or whether it’s even possible with current approaches.

Current limitations suggest areas where breakthroughs might be needed. Modern AI systems struggle with reasoning, common sense, genuine understanding of causality, and learning from small amounts of data the way humans can. Addressing these limitations might require new insights as fundamental as the Transformer architecture or perhaps entirely new paradigms we haven’t yet conceived.

The field has become more interdisciplinary than ever, drawing on insights from neuroscience, cognitive science, linguistics, philosophy, and many other fields. This cross-pollination might lead to new approaches that transcend current limitations.

One thing seems certain: AI will continue to profoundly impact society, raising questions about employment, education, creativity, privacy, security, and what it means to be human in an age of intelligent machines. These aren’t just technical challenges but deeply human ones that require input from philosophers, ethicists, policymakers, and society at large.

Conclusion: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

The AI systems we interact with today represent the culmination of decades of work by thousands of researchers, each building on the insights and learning from the mistakes of those who came before. From Turing’s theoretical foundations to modern Transformers, from expert systems to deep learning, from AI winters to AI springs, the journey has been long, winding, and fascinating.

Understanding this history helps us appreciate both how far we’ve come and how much remains unknown. The pioneers of the 1950s had bold visions that took far longer to realize than they imagined. Today’s researchers stand on firmer ground, with powerful tools and deep insights, but they too are pushing against the boundaries of the unknown.

As you continue learning about AI, remember that you’re joining a journey that began long before you and will continue long after. The questions that drove Turing, McCarthy, and their contemporaries—questions about intelligence, learning, and what machines can ultimately achieve—remain as compelling today as they were decades ago. Each new advance in AI doesn’t just solve problems; it raises new questions and opens new possibilities.

The history of AI teaches us humility in prediction, patience in progress, and excitement about possibilities. It shows us that setbacks can lead to insights, that persistence matters, and that today’s impossible often becomes tomorrow’s routine. Most importantly, it reminds us that artificial intelligence isn’t just a technical field it’s a human endeavor, driven by curiosity, creativity, and the desire to understand intelligence itself.

Welcome to this ongoing story. The history you’ve learned here isn’t just past, it’s prologue to a future that researchers, developers, and users like you will help create.