Introduction

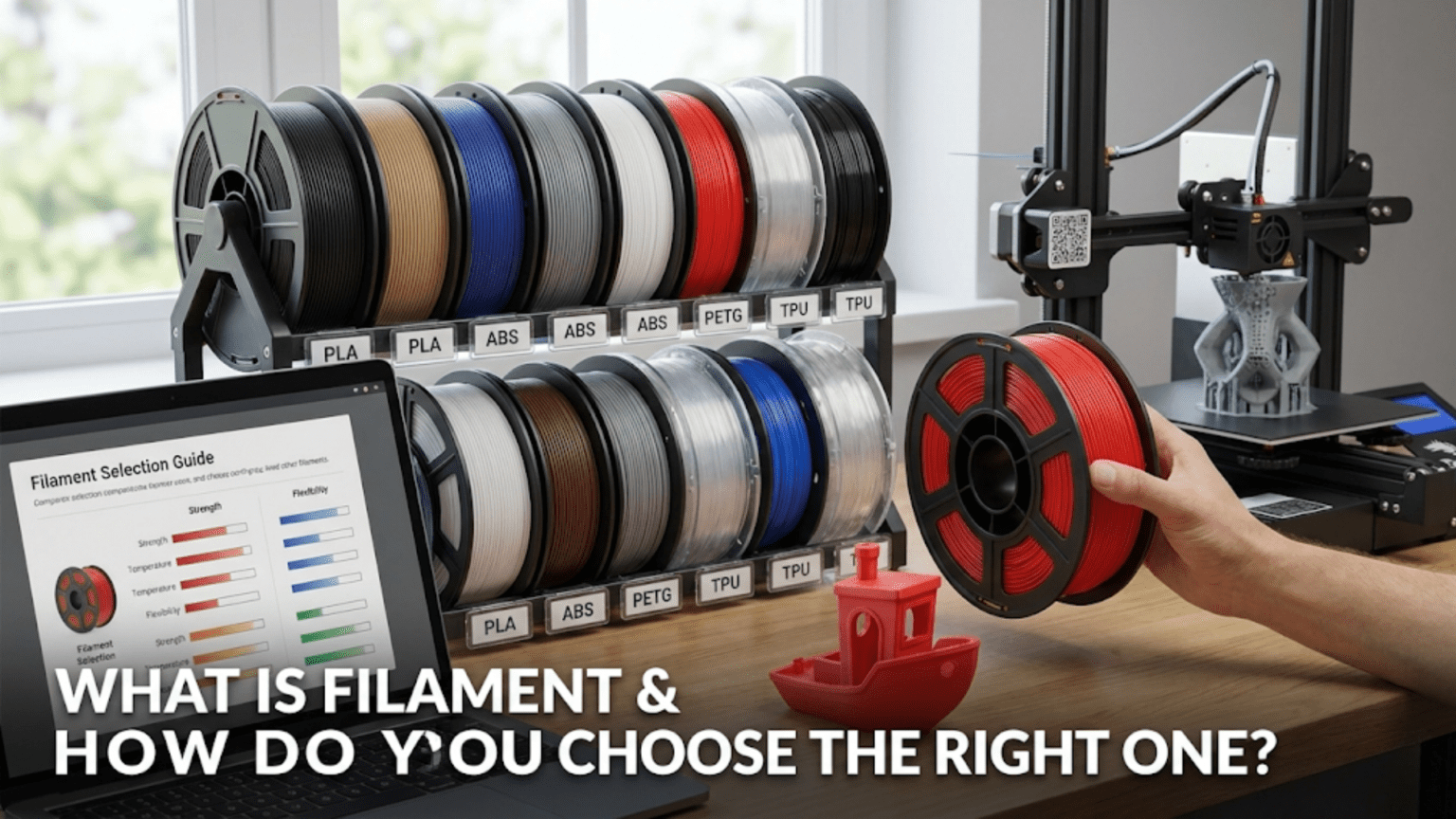

For FDM three-dimensional printing, filament represents the raw material that transforms from spooled plastic wire into finished objects through the additive manufacturing process. This seemingly simple component—essentially just plastic wound onto a spool—actually encompasses a diverse universe of materials with dramatically different properties, printing characteristics, and appropriate applications. Selecting the right filament for a specific project can mean the difference between parts that perform beautifully and failures that waste time and material, yet newcomers often face bewildering arrays of options without clear guidance about what differentiates them or which to choose.

Understanding filament begins with recognizing that the generic term encompasses dozens of distinct thermoplastic materials, each formulated with specific mechanical properties, thermal characteristics, and processing requirements. The most common materials like PLA, PETG, and ABS represent just the beginning of available options that extend through engineering plastics like nylon and polycarbonate to exotic specialty filaments containing wood fibers, metal particles, carbon fiber reinforcement, or even conductivity-enabling additives. Each material offers particular advantages while imposing specific limitations and printing challenges.

The physical characteristics of filament itself matter beyond just the material type. Filament diameter must match the printer’s specifications, typically 1.75mm or 2.85mm, with consistency across the spool affecting print quality. Manufacturing quality determines whether diameter stays uniform or varies significantly, whether the plastic contains contaminants or air bubbles, and whether the material has been properly formulated and dried. Premium filaments from reputable manufacturers typically exhibit better consistency and fewer defects than budget alternatives, though the price premium may not always justify the quality difference depending on application requirements.

Material selection depends on what properties the finished part requires: mechanical strength, flexibility, temperature resistance, chemical resistance, ease of printing, surface finish, or specific functional characteristics. A decorative object visible in someone’s home demands different properties than a mechanical component under load or an outdoor part exposed to weather. Understanding these requirements and matching them to appropriate materials represents essential knowledge for producing successful functional parts rather than just printable objects that happen to work sometimes.

This comprehensive guide will explore what filament is and how it works as the raw material for FDM printing, what the major material categories are and their respective characteristics, what mechanical and thermal properties distinguish different materials, how to match filament selection to project requirements, what specialty and exotic filaments exist and when they provide value, what quality factors affect filament performance, and how to store and handle filament properly. Whether selecting first filament purchases or exploring advanced materials for demanding applications, understanding filament fundamentals enables informed decisions that optimize results for specific needs.

Understanding Filament as Raw Material

Filament in FDM printing serves as the feedstock that gets melted, deposited, and solidified into the final printed object. Understanding its physical nature and how it functions in the printing process reveals what characteristics matter for successful printing.

The physical form of filament is a long continuous strand of thermoplastic material wound onto spools. Standard filament diameters are 1.75mm and 2.85mm (sometimes called 3mm though actual diameter is slightly smaller). The 1.75mm size has become more common in recent years, particularly for consumer printers, while 2.85mm remains popular in some printer lines. Using the wrong diameter obviously will not work, as the extruder mechanism is designed for specific filament size.

Thermoplastic behavior means the material becomes pliable when heated and solidifies when cooled, allowing repeated heating and cooling cycles. This characteristic enables the FDM process where solid filament melts in the hotend, deposits in semi-liquid form, and quickly solidifies into the intended shape. Not all plastics are thermoplastics—thermoset plastics cannot be remelted once cured—but FDM requires thermoplastic materials for its additive process to work.

Manufacturing processes for filament involve extruding molten plastic through dies to create continuous strands of consistent diameter, then winding them onto spools. Quality control during this manufacturing determines diameter consistency, roundness, and freedom from contamination. Premium manufacturers maintain tight tolerances and rigorous testing, while budget producers may allow greater variation. This manufacturing quality directly affects printing reliability and quality.

Diameter tolerance specifications indicate how much actual diameter varies from nominal size along the filament length. Premium filaments maintain ±0.03mm tolerance, while budget options might vary by ±0.05mm or more. Tighter tolerances produce more consistent extrusion because the extruder pushes a consistent volume per unit length. Wide variations cause alternating over- and under-extrusion as diameter changes, creating surface defects and dimensional inaccuracy.

Roundness or circularity affects how smoothly filament feeds through the extruder mechanism. Perfectly round filament slides through tubes and around curves without resistance. Oval or flat sections create friction and inconsistent extrusion. Quality manufacturers ensure roundness along with diameter tolerance, while poor manufacturing creates irregularly shaped filament that causes feeding problems.

Moisture absorption affects many filament materials because thermoplastics absorb water from ambient air at varying rates. This absorbed moisture creates problems during printing as water vaporizes in the hotend, creating bubbles, steam, and surface defects. Materials vary dramatically in moisture sensitivity, with nylon extremely hygroscopic while PLA relatively moisture-resistant. Understanding and managing moisture for sensitive materials prevents quality problems.

Spool winding quality determines whether filament unwinds smoothly during printing or causes tangles and resistance. Well-wound spools with uniform tension feed reliably. Poorly wound spools develop crossed strands that catch and create sudden resistance, potentially causing print failures. Premium manufacturers inspect and ensure proper winding, while budget producers sometimes ship tangled or improperly wound spools.

Color and additives affect not just appearance but printing characteristics. Pigments and dyes change how plastic flows and its optimal printing temperature. Different colors of the same base material may require temperature adjustments of 5-10 degrees. Additives for special effects, strength enhancement, or functional properties similarly modify printing behavior. Understanding that “PLA” is not a single uniform material but varies by color and additives prevents confusion when different spools print differently.

PLA: The Beginner-Friendly Standard

Polylactic acid or PLA represents the most popular filament for consumer 3D printing due to its ease of use, low printing temperature, minimal warping, and biodegradable origins from renewable resources. Understanding PLA’s characteristics explains its dominance while revealing its limitations.

Printing ease makes PLA ideal for beginners because it tolerates wide parameter ranges and forgives minor setup issues. The material adheres well to most build surfaces without heated beds, though heating to 50-60°C improves reliability. PLA prints successfully at relatively low temperatures around 190-220°C, requiring less energy than high-temperature materials. The low warping tendency means prints complete successfully without enclosures or extensive bed adhesion preparation.

Mechanical properties of PLA provide adequate strength for many applications while remaining relatively brittle compared to materials like ABS or nylon. PLA parts resist tensile forces reasonably well but crack rather than deform under impact. The material works well for decorative objects, prototypes, models, and low-stress functional parts. Applications requiring toughness, flexibility, or impact resistance need different materials.

Temperature resistance limitations restrict PLA to room-temperature applications because the glass transition around 60°C means parts deform when exposed to heat. Leaving PLA parts in hot cars or near heat sources causes warping and softening. Outdoor applications in summer sunlight may experience deformation. Applications requiring heat resistance must use higher-temperature materials like ABS, PETG, or engineering plastics.

Surface finish from PLA typically appears smooth and matte, accepting paint, gluing, and other post-processing readily. The material sands and files easily, allowing surface refinement when needed. PLA vapor smoothing is possible using solvents like ethyl acetate, though less common than acetone smoothing for ABS. Available color options span the full spectrum with various finishes from matte to glossy to translucent.

Biodegradability claims surrounding PLA are technically accurate but practically misleading. While PLA derives from renewable corn starch or sugar cane and theoretically biodegrades under industrial composting conditions, it does not break down in typical landfills, home compost, or natural environments within reasonable timeframes. The environmental benefits versus petroleum-based plastics are real but modest. Marketing emphasis on biodegradability should not suggest PLA products disappear naturally.

Variants and specialty PLA formulations include PLA+ with impact modifiers for improved toughness, silk PLA with additives creating glossy finishes, matte PLA with flattened appearance, and translucent PLA for light-passing applications. These variants maintain PLA’s basic ease of printing while modifying specific properties for targeted applications.

PETG: The Practical Middle Ground

PETG (polyethylene terephthalate glycol) occupies a practical middle ground between PLA’s ease of printing and engineering plastics’ superior properties. Understanding PETG’s characteristics helps recognize when it provides the optimal balance for applications.

Strength and toughness exceed PLA significantly, with PETG parts resisting impact and deformation better while maintaining reasonable rigidity. The material bends rather than breaking under stress that would fracture PLA. This toughness makes PETG suitable for functional parts, mechanical components, containers, and applications where parts might experience dropping or impact.

Temperature resistance surpasses PLA with glass transition around 80°C, allowing PETG parts to withstand moderately elevated temperatures without deformation. Parts can tolerate hot water, warm environments, and modest heat exposure that would deform PLA. However, PETG still cannot handle truly high temperatures like some engineering plastics, limiting use in high-heat applications.

Chemical resistance makes PETG suitable for containers, packaging, and applications involving mild chemicals or cleaning agents. The material resists many common chemicals, oils, and solvents better than PLA. Water bottles use PET (PETG’s chemical relative), indicating the material’s suitability for water and food contact applications when using food-safe grades.

Printing characteristics demand more attention than PLA but remain manageable for users with basic experience. PETG requires higher temperatures around 230-250°C and benefits from heated beds at 70-85°C. The material is notably sticky when molten, requiring careful retraction tuning to manage stringing. Cooling should be moderate—less aggressive than PLA but more than ABS—requiring balance to prevent sagging while maintaining layer adhesion.

Layer adhesion with PETG typically exceeds both PLA and ABS, creating very strong bonds between layers that approach or match the strength of solid material. Parts rarely delaminate along layer lines. This superior bonding contributes to overall part toughness and makes PETG excellent for functional applications where layer adhesion might otherwise be a weakness.

Surface finish appears glossy and somewhat translucent even in nominally opaque colors. PETG’s aesthetic differs from PLA’s matte appearance, with higher sheen and slight transparency. The material can be post-processed through sanding, though it tends to gum up sandpaper more than PLA. Chemical smoothing options exist but are less developed than for ABS.

Flexibility relative to PLA makes PETG parts slightly compliant, allowing some give under load without breaking. This characteristic helps impact resistance but may be undesirable for applications requiring absolute rigidity. The flexibility is modest—far less than dedicated flexible materials like TPU but noticeably more than rigid PLA.

ABS and Engineering Materials

ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) and related engineering thermoplastics offer superior mechanical properties and temperature resistance at the cost of more demanding printing requirements. Understanding these materials helps determine when their advantages justify the printing challenges.

ABS properties include excellent toughness, good temperature resistance with glass transition around 105°C, and chemical resistance to many substances. ABS parts withstand impacts that would fracture PLA, tolerate heat that would deform PETG, and resist various chemicals and cleaning agents. The material represents the plastic used in LEGO bricks, illustrating its durability and appropriate applications.

Printing challenges make ABS notoriously difficult for beginners, with warping representing the primary struggle. ABS’s high thermal contraction creates strong internal stresses during cooling. Without proper thermal management, parts warp severely, corners lift from the bed, and prints fail frequently. Successful ABS printing typically requires heated beds at 100-110°C, heated enclosures maintaining elevated ambient temperature, and careful attention to bed adhesion.

Enclosure requirements for reliable ABS printing prevent rapid cooling that causes warping and layer adhesion problems. Enclosures trap heat from the heated bed, creating warm stable environments where parts cool gradually and uniformly. Many users build cardboard or acrylic enclosures around printers specifically for ABS printing. Without enclosures, ABS prints frequently warp or fail except for very small parts.

Fumes from ABS during printing create health concerns because the material releases styrene and other volatile compounds when heated. Adequate ventilation is essential when printing ABS, either through enclosures vented outdoors or printing in well-ventilated spaces. The unpleasant odor serves as a warning that problematic chemicals are present. Users sensitive to fumes may avoid ABS entirely.

Acetone smoothing provides unique post-processing capability where ABS parts can be exposed to acetone vapor that melts surface layers, creating glossy smooth finishes that hide layer lines. This technique produces results impossible with other common materials, making ABS attractive for applications demanding smooth professional appearance. The acetone bath or vapor chamber technique requires safety precautions but achieves remarkable results.

Nylon (polyamide) offers exceptional strength, toughness, and wear resistance for demanding mechanical applications. The material requires high printing temperatures around 240-270°C and active drying before use due to extreme moisture sensitivity. Nylon’s slippery surface and excellent layer bonding create parts suitable for bearings, gears, living hinges, and structural components.

Polycarbonate provides extreme strength and temperature resistance, withstanding temperatures above 140°C and delivering impact resistance exceeding most other thermoplastics. Printing polycarbonate demands temperatures around 270-310°C, requiring all-metal hotends and often heated chambers. The difficulty justifies itself for applications requiring material properties PLA, PETG, and ABS cannot provide.

Specialty and Functional Filaments

Beyond standard thermoplastics, specialty filaments incorporate additives or use alternative materials to provide unique properties, appearances, or functional capabilities. Understanding these options reveals possibilities beyond conventional printing.

Flexible filaments based on TPU (thermoplastic polyurethane) create rubber-like parts with varying shore hardness from soft and flexible to firm and resilient. These materials enable printing gaskets, seals, dampeners, wearable items, and compliant mechanisms. Printing flexible filament demands very slow speeds, often requires direct drive extruders, and needs special attention to retraction settings. The material properties span from extremely flexible to semi-rigid depending on formulation.

Wood-filled filaments blend PLA or other base materials with fine wood particles, creating parts with wood-like appearance, texture, and even smell. The wood content ranges from 20-40%, giving printed objects authentic wood aesthetics that sand and stain like real wood. These filaments suit decorative applications, artistic prints, and situations where wood appearance is desirable. The wood particles can clog nozzles, typically requiring larger nozzle sizes like 0.5-0.6mm.

Metal-filled filaments incorporate brass, copper, bronze, steel, or other metal particles in PLA or other carriers. The resulting prints have metallic appearance, feel heavier than pure plastic, and can be polished to metallic sheen. Actual metal content ranges from 30-80% by weight. While not having metal’s structural properties, these filaments create convincing metal aesthetics. The abrasive metal particles wear brass nozzles, typically requiring hardened steel nozzles.

Carbon fiber reinforced filaments add short carbon fibers to base materials like PLA or nylon, significantly increasing stiffness and strength while reducing weight. These composite filaments produce lightweight rigid parts suitable for structural applications, RC components, and engineering uses. The carbon fibers are extremely abrasive, mandating hardened steel or ruby nozzles. The material costs considerably more than standard filaments but delivers properties justifying the expense for appropriate applications.

Conductive filaments enable printing circuits, sensors, and capacitive touch interfaces by incorporating carbon black or metal particles that conduct electricity. The conductivity level varies by formulation, with some suitable for low-current applications and others enabling resistive heating or basic circuitry. These specialty materials enable unique applications impossible with non-conductive plastics.

Glow-in-the-dark filaments contain phosphorescent particles that charge under light and glow in darkness. The glow intensity and duration vary by formulation, with some glowing brightly for hours while others provide subtle effects. Slightly abrasive particles suggest using hardened nozzles for extended printing. Applications include novelty items, safety markers, and decorative objects where luminescence adds value.

Color-changing filaments respond to temperature or UV exposure by changing color, enabling interactive or temperature-indicating applications. Thermochromic filaments change color at specific temperatures, useful for temperature visualization. UV-reactive filaments change under sunlight or UV lamps. These specialty materials cost more than standard filaments but enable unique functionality.

Dissolvable support materials like PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) enable printing complex multi-material parts where supports dissolve in water after printing. PVA pairs with PLA in dual-extrusion setups, printing support structures that wash away completely, leaving clean surfaces where supports were. The material is very moisture-sensitive and expensive but invaluable for extremely complex geometries.

Conclusion

Filament selection fundamentally determines what materials properties finished parts exhibit, what printing challenges users face, and what applications become viable. Understanding material options from beginner-friendly PLA through practical PETG to demanding engineering plastics and specialty composites enables matching materials to project requirements rather than defaulting to whatever filament happens to be loaded.

PLA’s ease of use, low temperature requirements, and minimal warping make it ideal for learning, decorative objects, and low-stress applications. Its limitations in temperature resistance and brittleness restrict use in functional parts exposed to heat or impact. PETG balances improved mechanical properties and temperature resistance against moderate printing difficulty, making it practical for functional parts requiring more than PLA provides. ABS and engineering materials offer superior properties but demand expertise and equipment to print successfully.

Specialty filaments enable unique capabilities from wood aesthetics to metal appearance to electrical conductivity that standard materials cannot provide. These options expand possibilities beyond conventional printing but typically cost more and present printing challenges justifying their use only when their unique properties provide genuine value.

Quality factors including diameter tolerance, roundness, moisture content, and manufacturing consistency affect print reliability and quality. Premium filaments cost more but typically deliver better results and fewer failures than budget alternatives. Understanding what quality characteristics matter helps evaluate whether spending more for better filament justifies the cost for specific applications.

Proper storage in sealed containers with desiccant protects moisture-sensitive materials and extends filament lifespan. Understanding material-specific requirements prevents degradation that causes printing problems. The investment in proper handling and storage pays dividends in reliable printing and reduced waste from degraded materials.

Mastering filament selection transforms material from an afterthought into a strategic choice that enables producing parts optimized for their intended purposes. Whether selecting first purchases or exploring advanced materials, understanding these fundamental characteristics enables informed decisions that improve results while avoiding frustration from inappropriate material choices.