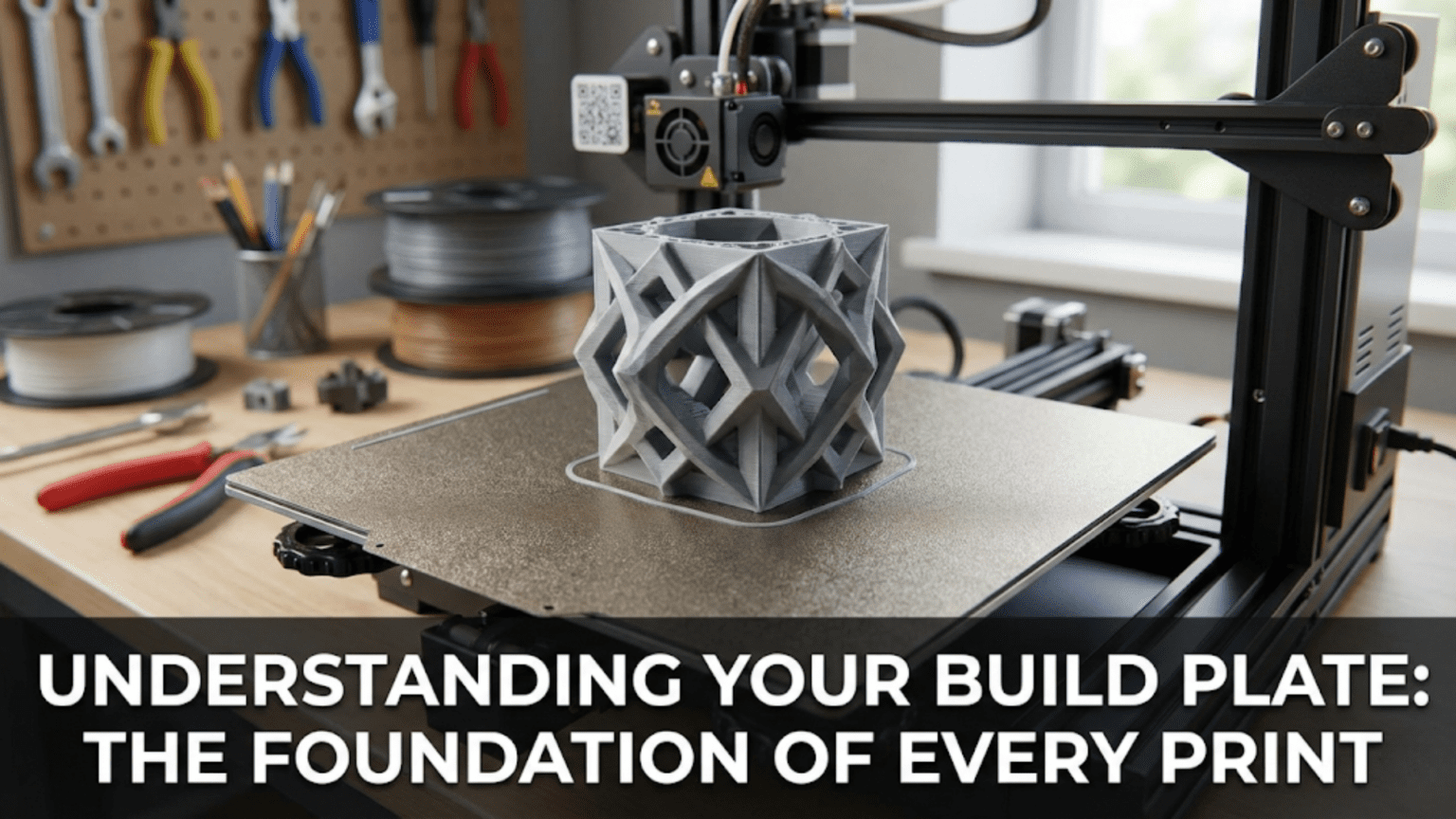

The build plate (also called the print bed) is the flat surface where your 3D printer deposits material to create objects, serving as the foundation upon which every layer is built. It typically includes a heating element to warm the surface for improved adhesion, a mounting system to keep it stable and level, and a surface material optimized for specific filament types to ensure prints stick during creation but release easily when finished.

Introduction

Every building needs a solid foundation, and 3D printing is no different. The build plate—that seemingly simple flat surface at the bottom of your printer—represents one of the most critical components in the entire system. Get it right, and your prints stick perfectly, build accurately, and release cleanly when finished. Get it wrong, and you’ll face a frustrating parade of failed prints, warped parts, and wasted filament.

Yet the build plate often receives less attention than flashier components like the hotend or extruder. Beginners sometimes view bed leveling as a tedious chore rather than understanding the underlying principles that make it necessary. The relationship between temperature, surface material, and adhesion remains mysterious to many users who simply follow recipes without understanding why certain approaches work.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore every aspect of the build plate—from its physical construction and heating mechanisms through the chemistry of adhesion and the various surface materials available. You’ll understand why proper leveling matters so much, how temperature affects different materials, and which surface choices work best for your specific needs. By the end, you’ll transform your build plate from a source of frustration into a reliable foundation for printing success.

The Build Plate’s Primary Functions

The build plate serves multiple critical roles simultaneously, each essential for successful printing:

Creating a Reference Plane

The build plate establishes the Z=0 reference plane—the starting point from which all vertical measurements begin. Your slicer software assumes this plane exists as a perfectly flat surface at a known height. The printer measures all subsequent layer positions relative to this reference.

When the nozzle deposits the first layer, it must be positioned at a very specific height above the build plate—typically 0.1 to 0.3mm depending on your layer height settings. Too far away, and the extruded plastic doesn’t squish against the surface adequately, creating poor adhesion. Too close, and the nozzle scrapes the bed or completely blocks plastic flow.

This reference plane requirement explains why build plate flatness matters tremendously. A warped or uneven bed means different areas sit at different heights. Your nozzle might be perfectly positioned over one section but too close or too far in another section just centimeters away.

Providing Adhesion During Printing

While the print builds, it must remain firmly attached to the build plate. Any movement during printing ruins dimensional accuracy and typically causes complete print failure. The build plate surface must grip the first layer securely enough to resist the forces involved in printing.

These forces include:

Nozzle drag: As the nozzle moves across the print surface, it contacts the plastic slightly, creating shear forces that try to move the print.

Thermal contraction: Most plastics shrink as they cool. If the bottom layer is firmly attached to the warm bed while upper layers cool and contract, internal stresses develop. These stresses try to lift corners and edges off the bed—a failure mode called warping.

Acceleration forces: When the print head accelerates or decelerates rapidly (especially with larger, heavier prints), inertia creates forces trying to move the print.

Layer deposition forces: Each new layer being deposited applies downward and lateral forces as the nozzle drags slightly through the molten plastic.

The surface must provide enough adhesion to overcome all these forces throughout the entire print duration, which might last many hours for large objects.

Enabling Easy Release When Finished

Paradoxically, after gripping the print firmly throughout the printing process, the build plate must allow easy removal when printing completes. Prints that stick too aggressively can be nearly impossible to remove without damage, risk breaking the print or the build surface, and make the bed leveling process frustrating.

The ideal build surface provides strong adhesion during printing but releases cleanly afterward. Temperature plays a key role here—many surfaces grip hot plastic firmly but release it easily once cooled. Others achieve this balance through surface texture, chemistry, or removable flexible sheets.

Distributing Heat Evenly

For heated beds, uniform temperature distribution prevents problems. If one area of the bed runs hotter than another, prints spanning multiple zones experience different adhesion characteristics and thermal behavior. Hot spots can cause excessive adhesion or material degradation, while cool spots may not provide adequate adhesion.

The build plate’s thermal mass and the heating element’s design both affect temperature uniformity. Better designs distribute heat evenly across the entire surface, maintaining consistent temperatures within a few degrees regardless of position.

Build Plate Construction and Components

The Structural Base

The foundation of most build plates consists of a rigid substrate that resists bending and warping. This base must remain flat under the thermal stresses of repeated heating and cooling cycles while supporting the weight of prints and any mechanical loads from the bed leveling system.

Aluminum tooling plate represents the most common choice for quality printers. This material is specifically manufactured for precision applications, undergoing processes to relieve internal stresses that could cause warping. Aluminum offers excellent thermal conductivity for even heat distribution, machines to very tight flatness tolerances (often within 0.1mm across the entire surface), and remains stable across temperature cycling.

Thickness affects performance significantly. Thinner plates (2-3mm) heat faster and reduce overall bed weight, benefiting printers where the bed moves in the Y-axis. However, thin plates flex more easily and show greater thermal gradients. Thicker plates (5-8mm) provide superior flatness and thermal mass but heat more slowly and add weight.

Cast aluminum costs less than precision-ground tooling plate but may not be as flat initially. Some manufacturers mill these castings to improve flatness, but quality varies considerably. Cast beds often work adequately for smaller printers but may show flatness issues on larger formats.

Glass provides an inherently flat surface at low cost. Borosilicate glass handles thermal cycling better than standard glass, resisting thermal shock when transitioning between temperatures. Glass offers perfect flatness across its surface but has poor thermal conductivity compared to aluminum, creating longer heat-up times and potential temperature variations.

Some printers use glass laid atop an aluminum heating element, combining aluminum’s heating characteristics with glass’s flatness. Clips or other mounting systems hold the glass in place while allowing removal for cleaning or print removal.

Steel appears in some designs, particularly for magnetic build surfaces. Spring steel provides flexibility that allows bending the sheet to pop prints off easily. The magnetic mounting allows quick surface changes without tools.

PCB material serves as both the structural base and heating element in some budget printers. These designs etch resistive traces directly onto a printed circuit board substrate. While cost-effective, PCB beds typically offer lower quality flatness and may degrade faster than dedicated aluminum plates with separate heaters.

Heating Elements

The heating element transforms electrical power into thermal energy, warming the build surface to temperatures that improve adhesion for various materials.

PCB heaters use etched copper traces on a circuit board that resist electrical current flow, generating heat through resistive heating. The trace pattern distributes heating across the bed area. These heaters bond directly to the aluminum plate or integrate into a single PCB that serves as both heater and structural base.

PCB heaters can achieve excellent temperature uniformity through careful trace design. However, they’re permanently attached to the plate, so heater failure often means replacing the entire bed assembly.

Silicone mat heaters use resistive wire embedded in flexible silicone material. These adhere to the underside of aluminum plates with high-temperature adhesive or mechanical mounting. Silicone heaters distribute heat well and can be replaced independently if they fail.

Quality silicone heaters undergo careful design to ensure even heat distribution despite the wire pattern. Better designs use meandering patterns that provide more uniform spacing across the surface area.

Mains voltage vs. low voltage represents an important electrical distinction. Most 3D printers use 12V or 24V DC heaters powered by the printer’s main power supply. These require relatively safe low voltages but draw high currents (often 10-15 amps for larger beds), necessitating heavy wire gauges and robust power supplies.

Some larger printers use mains voltage heaters (120V or 240V AC) that draw lower current for the same wattage. These heat faster and require lighter wiring but introduce higher voltage risks and typically require relays for control rather than direct connection to the printer’s mainboard.

Power requirements scale with bed size. A small 200mm x 200mm bed might use 100-150 watts, heating to printing temperature in 3-5 minutes. A large 400mm x 400mm bed could require 500-750 watts, taking 10-15 minutes to reach temperature. Insufficient heater power means long waits and potential inability to maintain temperature if heat loss exceeds heating capacity.

Temperature Sensing

Accurate temperature measurement ensures the bed reaches and maintains target temperatures. Most printers use thermistors similar to those in hotends—temperature-dependent resistors that change resistance predictably with temperature.

Bed thermistors typically mount in one of two ways:

Embedded thermistors sit in holes drilled partway through the aluminum plate, placing them in close thermal contact with the build surface. Thermal paste fills any air gaps to improve heat transfer. This placement provides accurate surface temperature measurement.

Surface-mounted thermistors attach to the bottom of the heating element with adhesive or thermal pads. While easier to install, this placement measures heater temperature rather than actual build surface temperature. The thermal resistance between heater and surface can create temperature offsets, particularly with glass beds where the glass acts as an insulator.

Some advanced beds use multiple thermistors at different locations, allowing the firmware to monitor temperature uniformity and detect failing heaters or thermistors. The firmware can also adjust heating algorithms based on multiple temperature inputs for better control.

Mounting and Leveling Systems

The build plate must mount to the printer’s frame securely while allowing adjustment for leveling (tramming) to make it perpendicular to the Z-axis.

Four-point leveling uses four adjustment screws, typically located at the corners. Each screw passes through the printer’s frame and pushes against springs that support the bed plate. Turning a screw clockwise raises that corner; counterclockwise lowers it. This represents the most common configuration on consumer printers.

The four-point system requires patience since adjustments interact—changing one corner affects the others. Most users develop a systematic approach, checking center points between adjustment screws and iterating until the entire surface sits at the correct height.

Three-point leveling uses only three adjustment points, usually in a triangular pattern. This kinematic mounting mathematically guarantees a stable plane (three points always define a plane, while four points might rock). Three-point systems are theoretically superior but less common in consumer printers, perhaps because users expect to see adjustment screws in all four corners.

Fixed beds with automatic compensation eliminate manual adjustment entirely. The bed mounts rigidly to the frame in a fixed position. Automatic bed leveling probes measure the actual bed position at multiple points, creating a mesh that maps surface height across the area. During printing, the firmware adjusts Z-height dynamically based on the X and Y position, compensating for any tilt or warping in software rather than mechanical adjustment.

Some high-end printers combine automatic probing with motorized adjustment—the printer automatically adjusts the leveling screws based on probe measurements, achieving perfect tramming without manual intervention.

Insulation

Heat escapes from the bed’s underside, wasting energy and extending heat-up times. Insulation reduces this heat loss, improving efficiency and temperature stability.

Cork sheets provide simple, effective insulation. These stick to the bottom of the heating element, reducing heat loss downward. Cork tolerates high temperatures, costs little, and installs easily.

Ceramic fiber insulation offers superior performance. This material—similar to that used in kiln insulation—provides excellent thermal resistance at high temperatures. However, some types contain materials requiring careful handling during installation.

Foam insulation works but requires high-temperature varieties. Standard foam degrades at bed operating temperatures. Specialized high-temperature foam designed for insulation purposes performs better.

Insulation thickness involves tradeoffs. Thicker insulation provides better thermal performance but adds height to the Z-axis stack, reducing available build height in printers with limited Z-travel. Most implementations use 3-10mm thick insulation as a practical compromise.

Build Surface Materials and Characteristics

The top surface material—the actual material your plastic contacts—dramatically influences adhesion success and print quality. Different materials suit different filaments and offer varying maintenance requirements.

Glass Surfaces

Glass provides the oldest and still popular build surface material. Its advantages include:

Perfect flatness: Glass manufactured for printing applications is exceptionally flat, often within 0.1mm across the entire surface.

Durability: Glass lasts essentially forever with proper care, never wearing out or degrading.

Smooth finish: Prints develop perfectly smooth, glossy bottom layers that look professional.

Easy cleaning: Most adhesives and residue wipe away easily with isopropyl alcohol or scraping.

Low cost: Plain glass costs little, and borosilicate glass—which handles thermal shock better—remains affordable.

However, glass also presents challenges:

Requires adhesion aids: Plain glass doesn’t provide enough natural adhesion for most materials. Users typically apply glue stick, hairspray, or other aids.

Clips needed: The glass must mount atop the heated bed with clips or other retention systems. These clips can interfere with prints near bed edges.

Slower heating: Glass’s poor thermal conductivity means slower heat-up times and potential temperature variations across the surface.

Breakage risk: Dropped tools or removing stuck prints aggressively can crack or chip glass surfaces.

Thermal expansion: Glass expands when heated, though borosilicate minimizes this characteristic. The clips must allow some movement while maintaining position.

Different glass treatments modify performance:

Plain glass works as-is with adhesion aids. Window glass functions adequately for small beds, though borosilicate offers better thermal shock resistance.

Frosted or textured glass roughens one surface, improving adhesion without aids for some materials. The textured surface also transfers to the print’s bottom layer, creating a pleasant matte finish rather than glossy smooth.

Mirror tiles provide extremely flat surfaces with a super-smooth finish. These work excellently for printing with glue stick or hairspray and produce beautiful bottom surfaces. However, they’re even slicker than regular glass without adhesion aids.

PEI (Polyetherimide) Surfaces

PEI has become extremely popular as a build surface material. This amber-colored engineering plastic offers excellent adhesion properties:

Strong hot adhesion: When heated, PEI grips most plastics firmly. PLA, PETG, and ABS all stick reliably.

Easy cold release: As prints cool, they release from PEI relatively easily. The thermal contraction helps break the adhesion bond.

No adhesion aids needed: PEI works directly with most materials without glue, tape, or sprays.

Good durability: Properly maintained PEI surfaces last for hundreds of prints.

Smooth finish: Prints develop smooth, professional-looking bottom layers.

PEI comes in several forms:

PEI sheets are thin films (typically 0.5-1mm thick) that adhere to glass or aluminum beds with high-temperature adhesive. These provide an economical way to add PEI to existing beds.

Powder-coated PEI applies a textured PEI coating to spring steel or aluminum. The textured surface improves adhesion while creating a pleasant textured finish on print bottoms.

Thick PEI sheets (2-3mm) can mount directly to beds without backing plates, though this is less common.

PEI requires proper care:

Clean surface: Skin oils and residue reduce adhesion dramatically. Clean with isopropyl alcohol before each print or whenever adhesion diminishes.

Light sanding: Over time, PEI becomes too smooth as the surface glazes. Light sanding with fine-grit sandpaper (400-800 grit) roughens the surface, restoring adhesion.

Avoid damage: Sharp tools scraping stuck prints can gouge PEI. Use appropriate removal techniques to avoid surface damage.

Temperature limits: PEI degrades above 200-220°C bed temperature for extended periods. Most printing uses lower bed temps, but high-temperature materials may exceed PEI’s capabilities.

Powder-Coated Spring Steel

This newer technology combines several innovations for exceptional convenience:

Magnetic mounting: A magnetic base plate attaches to the heated bed permanently. The spring steel sheet, with powder-coated PEI on one or both sides, simply lays on top, held by magnetic attraction.

Removable flexibility: After printing, remove the entire sheet and flex it. The spring steel’s flexibility combined with thermal contraction causes prints to pop off with minimal force.

Textured finish: The powder coat creates a textured surface that provides excellent adhesion while producing attractive textured bottom layers on prints.

Multi-surface options: Keep several sheets—smooth PEI, textured PEI, or specialized surfaces—and swap them instantly for different materials or finish preferences.

The powder coat texture varies by manufacturer. Some create subtle texture barely visible on prints. Others produce aggressive texture that shows prominently. Try different options to find your preference.

Limitations include:

Cost: These systems cost more than plain glass or PEI sheets.

Thickness: The magnetic base plus steel sheet assembly adds 2-4mm height, reducing available build volume on printers with limited Z-axis.

Flatness: Spring steel’s flexibility means it might not be perfectly flat, especially if damaged. Magnetic mounting helps hold it flat, but quality varies.

Coating wear: The powder coat eventually wears or chips with heavy use, though it typically lasts for many hundreds of prints.

BuildTak and Similar Surfaces

BuildTak and similar products use textured plastic sheets that adhere to the bed surface:

Strong adhesion: These provide excellent grip for many materials.

Easy application: Peel-and-stick backing makes installation simple.

Texture transfer: The surface texture transfers to print bottoms, creating an interesting appearance.

However, they also have notable drawbacks:

Wear and tear: The surface wears over time, developing smooth spots or gouges.

Difficult removal: When time comes to replace a worn surface, removing the old sheet and adhesive residue proves challenging.

Print removal difficulty: Parts can stick so firmly that removal risks damaging the print, especially with PETG.

Limited reusability: Once damaged, the sheet must be replaced entirely.

These surfaces work well for users who primarily print PLA and don’t mind periodic replacement, but PEI or powder-coated steel typically offer better long-term value.

Specialized Surfaces

Various specialty surfaces target specific needs:

Garolite (G10): This phenolic composite material handles high temperatures and provides excellent adhesion for nylon and other engineering plastics. It’s more specialized than general-purpose surfaces.

Polypropylene sheets: These release nylon prints easily, solving the challenge of nylon’s tendency to bond too firmly to most surfaces.

Painter’s tape: Blue painter’s tape applied to the bed provides adequate PLA adhesion in a pinch. It’s inexpensive and easily replaced but doesn’t work well for higher-temperature materials.

Kapton tape: This polyimide tape handles high temperatures and works well for ABS, though it’s relatively expensive and can be difficult to apply smoothly.

PVA glue: Water-soluble PVA (white glue) thinned with water creates a coating that improves adhesion on glass or other smooth surfaces. It washes off easily for cleaning.

Heated Beds: Temperature and Adhesion

Build plate heating dramatically improves printing success, particularly for materials prone to warping:

How Heating Improves Adhesion

Heat affects the plastic-to-surface interface in several ways:

Increases surface energy: Warmer surfaces typically exhibit higher surface energy, improving wetting and adhesion of deposited plastic.

Keeps plastic above glass transition temperature: For materials like ABS, keeping the bottom layers warm prevents them from hardening fully. The plastic remains slightly soft and pliable, reducing internal stresses that cause warping.

Reduces thermal gradient: A heated bed minimizes the temperature difference between the part’s bottom and top layers. Smaller gradients mean less thermal contraction stress pulling the part upward at corners and edges.

Improves material flow: Deposited plastic remains molten slightly longer on a warm surface, allowing better bonding to the surface and previous layers.

Temperature Requirements by Material

Different materials require different bed temperatures for optimal results:

PLA: 50-60°C bed temperature works well. PLA doesn’t technically need heating—it prints successfully on cold beds—but gentle warming improves first layer adhesion and reduces warping for larger prints.

PETG: 70-80°C provides good adhesion without making prints too difficult to remove. PETG can bond extremely firmly to some surfaces at higher temperatures.

ABS: 90-110°C bed temperature helps prevent the significant warping characteristic of this material. The high temperature keeps bottom layers warm, reducing thermal contraction stresses.

TPU and flexible materials: 40-60°C works for most flexible filaments. Too much heat can make these materials too soft to print well.

Nylon: 70-90°C helps adhesion, though nylon remains challenging on most surfaces regardless of temperature. Specialized surfaces like Garolite work better.

Polycarbonate: 110-130°C bed temperatures support this high-temperature material, though achieving these temperatures requires powerful heaters and good insulation.

These are starting points—exact optimal temperatures vary by specific filament formulation, surface material, and environmental conditions. Users often experiment to find ideal settings for their particular combination.

Temperature Uniformity Challenges

Achieving uniform temperature across the entire bed surface presents engineering challenges:

Center vs. edges: Without insulation, bed edges lose more heat to the environment than the center, creating cooler edges. This can cause adhesion problems or warping at print perimeters.

Heater layout: The resistive trace or wire pattern must distribute heat evenly. Poor designs create hot spots over heater elements and cool spots between them.

Thermal conductivity: The bed material’s thermal conductivity affects uniformity. Aluminum conducts heat well, evening out temperature variations. Glass conducts poorly, allowing temperature gradients to persist.

Sensor location: Most beds use a single thermistor that measures temperature at one point, typically near the center. If this doesn’t represent the average surface temperature accurately, the control system can’t maintain uniform heating.

Better bed designs address these challenges through:

- Carefully optimized heater trace patterns

- Adequate heater power for the bed size

- Insulation beneath the heater

- High-conductivity bed materials

- Multiple temperature sensors in advanced systems

Heat-Up Times and Power Management

The time required to heat a bed depends on:

Heater power: Higher wattage means faster heating. A 200W heater brings a medium bed to temperature faster than a 100W heater.

Bed mass: Larger, heavier beds store more thermal energy and take longer to heat. Thin beds heat faster than thick ones.

Target temperature: Heating from room temperature to 60°C happens faster than reaching 110°C. The temperature difference drives heat flow, so heating slows as the bed approaches target temperature.

Insulation: Well-insulated beds waste less energy heating the environment and reach temperature faster.

Ambient conditions: Cold workshops require more energy to heat beds than warm environments.

Typical heat-up times range from 2-3 minutes for small, well-powered beds reaching PLA temperatures, to 10-15 minutes for large beds reaching ABS temperatures.

Bed Leveling: The Foundation of Success

Proper bed leveling (more accurately called tramming) ensures the build surface sits at the correct height relative to the nozzle across the entire printing area. This process represents one of the most critical maintenance tasks for print success.

Why Leveling Matters So Much

The first layer determines print success or failure. This layer must squish against the bed surface with just the right amount of pressure—enough to ensure firm adhesion and proper layer thickness, but not so much that the nozzle scrapes the bed or prevents plastic extrusion.

The acceptable Z-height window is remarkably small—typically only 0.05-0.1mm. If the nozzle is even 0.1mm too high, the first layer doesn’t squish adequately, creating poor adhesion and often leading to the print detaching partway through. If 0.05mm too low, the nozzle may scrape the bed or completely block plastic flow.

Given this tiny tolerance, bed flatness becomes critical. A bed that’s level in one corner but 0.2mm low in another means the nozzle height is correct in one area but completely wrong elsewhere. Manual leveling aims to position the entire bed surface within this narrow acceptable range.

Manual Leveling Process

The traditional manual leveling process uses the “paper test”:

Step 1: Heat the bed to printing temperature. Thermal expansion changes the bed’s position, so leveling cold produces incorrect results.

Step 2: Home all axes to establish the coordinate system.

Step 3: Disable stepper motors (most printers have a menu option for this) to allow manual positioning.

Step 4: Move the nozzle to the first leveling point, typically the front-left corner, positioning it near the adjustment screw.

Step 5: Place a piece of standard printer paper between the nozzle and bed surface.

Step 6: Adjust the leveling screw at that corner while sliding the paper back and forth. The nozzle should lightly drag on the paper—you feel resistance but can still move the paper.

Step 7: Repeat for each corner, then check the center points between screws.

Step 8: Iterate multiple times. Adjusting one corner affects the others, so several complete passes usually achieve good results.

Step 9: Verify by starting a test print with a large first layer that covers the entire bed. Watch carefully as it prints, ensuring the first layer squishes correctly across the whole surface.

This process requires patience and practice. Beginners often struggle with determining the “correct” paper drag feeling. Experience teaches you what works—enough resistance to feel the paper slightly catching but not so much that you can’t move it at all.

Automatic Bed Leveling

Automatic bed leveling systems use a probe to measure bed height at multiple points automatically:

Inductive probes detect metal surfaces electromagnetically. These work with metal beds but don’t sense glass or PEI directly. Many users attach aluminum squares at probe points on non-metal beds.

Capacitive probes sense changes in capacitance caused by the surface proximity. These detect various materials including glass and plastic.

BLTouch and similar devices use a deployable metal pin that physically contacts the surface. When contact occurs, the pin retracts slightly, triggering a switch that signals the printer. These work with any surface material.

The probing sequence measures bed height at a grid of points (commonly 3×3, 4×4, or 5×5). The firmware stores these measurements, creating a mesh map of the bed surface. During printing, the firmware consults this mesh and adjusts Z-height based on the current X and Y position, compensating for bed irregularities.

Automatic leveling offers several advantages:

Consistency: The probe measures the same way every time, eliminating human variation.

Compensation for warped beds: Even beds that aren’t perfectly flat work adequately since the mesh compensates for irregularities.

Convenience: Especially with automatic probing before each print, you don’t manually level frequently.

However, automatic leveling isn’t magic:

Gross adjustment needed: If the bed sits very far out of level, the mesh can’t compensate adequately. Manual adjustment gets the bed approximately level before relying on automatic compensation.

Probe offset matters: The probe measures at a different location than where the nozzle prints. The firmware applies a probe offset to account for this, but incorrect offsets cause problems.

Surface material sensitivity: Some probe types work better with certain surfaces. Capacitive probes might give inconsistent readings on textured surfaces.

Build Plate Surface Comparison

| Surface Type | Cost | Durability | Adhesion Quality | Release Ease | Maintenance | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain Glass | Low | Excellent | Moderate (needs aids) | Good | Low | Budget builds, smooth finishes |

| Textured Glass | Low | Excellent | Good | Good | Low | PLA, textured finishes |

| PEI Sheet | Medium | Good | Excellent | Very Good | Medium | General purpose, most materials |

| Powder-Coated Steel | High | Good | Excellent | Excellent | Low | Convenience, multi-material |

| BuildTak | Medium | Poor | Excellent | Moderate | High (replacement) | PLA-focused printing |

| Mirror | Low | Excellent | Moderate (needs aids) | Good | Low | Super-smooth finishes |

| Garolite | Medium | Good | Excellent (nylon) | Good | Medium | Engineering materials |

| Painter’s Tape | Very Low | Poor | Moderate (PLA) | Good | High | Temporary, budget |

Common Build Plate Problems and Solutions

First Layer Not Sticking

Symptoms: Print releases from bed immediately or after a few layers. First layer appears stringy or doesn’t adhere at all.

Causes and Solutions:

- Nozzle too far from bed: Re-level the bed, ensuring proper nozzle-to-bed distance

- Bed too cold: Increase bed temperature by 5-10°C

- Surface contamination: Clean thoroughly with isopropyl alcohol

- Wrong surface for material: Switch to a more compatible surface or add adhesion aids

- First layer speed too fast: Reduce first layer print speed to 20-30mm/s

- Insufficient first layer squish: Decrease first layer height or reduce Z-offset

Warping and Corner Lifting

Symptoms: Print corners lift off the bed during printing. Larger prints curl upward at edges.

Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient bed temperature: Increase bed temp, especially for ABS

- Thermal contraction stress: Use brim or raft for larger base area

- Drafts cooling the print: Eliminate air currents, use an enclosure for ABS

- Poor first layer adhesion: Ensure proper leveling and surface preparation

- Too much part cooling: Reduce part cooling fan speed, especially for initial layers

Prints Stuck Too Firmly

Symptoms: Completed prints won’t release from bed. Attempting removal risks damaging print or surface.

Causes and Solutions:

- Bed too hot: Reduce bed temperature by 5-10°C

- First layer over-squished: Increase nozzle height slightly during leveling

- Material-specific bonding: PETG particularly bonds strongly to some surfaces; lower temp or use release agent

- Allow complete cooling: Let bed cool to room temperature before attempting removal

- Use removal tools: Thin spatulas or flexible surfaces help with difficult releases

Uneven First Layer

Symptoms: First layer appears perfect in some areas but too thin or thick in others.

Causes and Solutions:

- Bed not level: Re-level more carefully, use automatic leveling if available

- Warped bed: Use mesh bed leveling to compensate, or replace warped bed

- Dirty surface: Clean entire surface uniformly

- Temperature variations: Improve bed insulation, check for failing heater sections

- Nozzle partially clogged: Clean or replace nozzle if extrusion appears uneven

Temperature Fluctuations

Symptoms: Bed temperature varies during heating or printing, bouncing above and below target.

Causes and Solutions:

- Poor PID tuning: Run PID autotune for the bed

- Inadequate power supply: Check that PSU provides sufficient current

- Loose thermistor: Secure thermistor properly, verify good thermal contact

- Failing heater or thermistor: Test components, replace if defective

- Ambient temperature changes: Insulate bed better, control workshop temperature

Upgrading and Maintaining Your Build Plate

When to Consider Upgrades

Build plate upgrades make sense when:

Current surface worn out: PEI that no longer adheres despite cleaning, BuildTak with gouges and smooth spots, or damaged glass justify replacement.

Material compatibility issues: If you’re moving to new materials incompatible with your current surface, upgrading opens new possibilities.

Convenience desired: Magnetic removable surfaces dramatically simplify print removal and workflow.

Temperature limitations: Higher-temperature materials might require bed upgrades to reach necessary temperatures.

Size changes: Moving to larger prints might reveal that your bed’s size, power, or flatness limits you.

Maintenance Best Practices

Regular maintenance keeps your build plate performing optimally:

Clean before every print: Quick wipe with isopropyl alcohol removes oils and residue. This simple habit prevents many adhesion problems.

Deep clean periodically: Monthly (or when needed), thoroughly clean with dish soap and water or appropriate solvents for stubborn residue.

Inspect for damage: Check regularly for scratches, gouges, warping, or coating degradation. Address issues before they cause print failures.

Verify leveling: Re-level when you notice first layer problems, after moving the printer, or periodically even if everything seems fine.

Check electrical connections: Verify thermistor and heater wiring periodically. Loose connections cause temperature control issues.

Replace worn surfaces: Don’t struggle with degraded surfaces. Fresh PEI or a new sheet costs little compared to failed prints and frustration.

Protect during maintenance: When working on the printer, cover the bed to prevent tool drops from damaging the surface.

Surface Treatment and Rejuvenation

Worn surfaces sometimes benefit from treatment rather than replacement:

PEI sanding: Light sanding with 400-800 grit sandpaper roughens glazed PEI, restoring adhesion. Sand in circular motions for even coverage.

Acetone wiping: Some users wipe PEI with acetone to roughen and clean it. This works but can damage PEI with overuse.

Glass polishing: Fine scratches on glass can be polished out with cerium oxide compound, though replacement might be more practical.

Adhesion aids: When surface adhesion degrades, adhesion promoters like glue stick, hairspray, or specialty products extend surface life.

Advanced Build Plate Concepts

Multi-Zone Heating

High-end printers sometimes implement divided heated beds with independent zones. This allows:

- Heating only the portion being printed, saving energy

- Compensating for uneven heat distribution

- Printing on one zone while another cools

- Precise temperature profiling across the bed

Implementation requires multiple heaters, thermistors, and control channels, adding complexity and cost.

Kinematic Coupling

Precision applications use kinematic mounting—three ball-and-cup joints that create a perfectly defined, repeatable position. The bed can be removed and returned to exactly the same position without re-leveling.

This expensive implementation appears primarily in high-end industrial machines rather than consumer printers.

Active Leveling

Some printers automatically adjust leveling screws using motors based on probe measurements. The user initiates automatic leveling, and the printer adjusts itself to perfect tramming without manual intervention.

This combines the precision of automatic probing with mechanical correction rather than software compensation.

Conclusion

The build plate serves as the literal foundation of every 3D print you create. Understanding its construction, heating characteristics, surface materials, and proper maintenance transforms this component from a source of frustration into a reliable partner in successful printing.

Whether you’re using simple glass with glue stick on a budget printer or a sophisticated powder-coated magnetic surface on a high-end machine, the principles remain the same. The bed must be flat, properly leveled, appropriately heated, and equipped with a surface that balances adhesion during printing with easy release afterward.

Success with build plates comes from understanding the interactions between temperature, surface chemistry, material properties, and mechanical setup. When problems arise—and they will, even for experienced users—this knowledge helps you diagnose root causes rather than randomly trying solutions.

Take time to properly level your bed, maintain your surface, and use appropriate temperatures for your materials. These fundamentals prevent more problems than any number of advanced features or expensive upgrades. A well-maintained basic bed outperforms a neglected premium surface every time.

As you continue your 3D printing journey, you’ll develop intuition for bed behavior. You’ll recognize when adhesion seems weak before starting a print, catch leveling issues from subtle first layer appearance changes, and understand which surfaces work best for your typical projects.

The build plate might not be the most exciting component in your printer, but it’s absolutely critical to your success. Master this foundation, and you’ll find your printing reliability improves dramatically, letting you focus on design and creation rather than fighting basic adhesion problems. Every successful print starts with a solid foundation—make sure yours is ready to support your creative visions.