Introduction

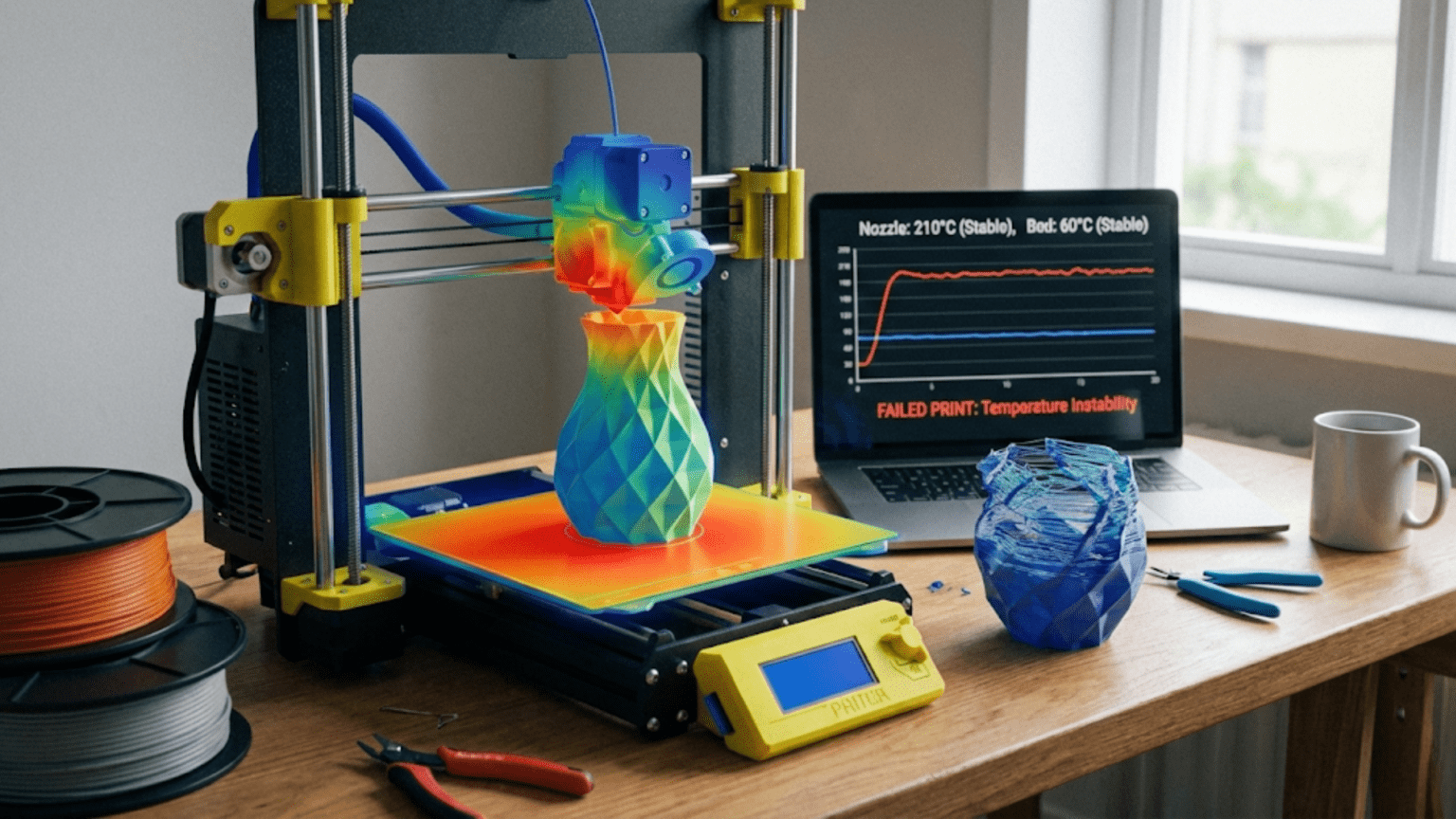

Temperature control represents one of the most fundamental yet frequently misunderstood aspects of successful three-dimensional printing. Every material used in additive manufacturing has specific temperature requirements that determine whether it flows properly through the nozzle, bonds adequately between layers, adheres to the build surface, and ultimately produces parts with acceptable quality and mechanical properties. Getting temperatures right makes the difference between successful prints and frustrating failures, yet the relationship between temperature and print outcomes involves complex interactions that extend beyond simply setting the hotend to a number suggested on a filament spool.

The thermal management in 3D printing occurs at multiple locations simultaneously: the hotend that melts material for extrusion, the build plate that affects first layer adhesion and warping, the material cooling after deposition, and the ambient environment surrounding the printer. Each temperature zone affects different aspects of print quality and success, creating an interconnected system where changes in one area ripple through others. Understanding these relationships enables intelligent optimization rather than blindly copying settings that may not work for your specific combination of printer, material, and environmental conditions.

Temperature effects manifest throughout the printing process in ways both obvious and subtle. Hotend temperature that is too low causes under-extrusion as viscous plastic cannot flow through the nozzle fast enough. Temperature that is too high creates excessive stringing and oozing as overly fluid plastic drips during travel moves. Bed temperature affects whether prints stick during building and release after cooling. Cooling rates determine surface quality on overhangs and bridges. Material-specific thermal properties mean optimal settings vary dramatically between PLA, PETG, ABS, nylon, and other plastics.

The challenge for users lies in determining appropriate temperatures for their specific situations rather than relying on generic recommendations that may not account for variations in material formulation, printer characteristics, or environmental conditions. A filament labeled “PLA” might print optimally anywhere from 190 to 220 degrees Celsius depending on its specific additives, colorants, and molecular weight. One printer’s “210 degrees” might actually run several degrees hotter or cooler than another printer’s setting due to thermistor calibration differences or thermal system design variations.

This comprehensive guide will explore how temperature affects material flow and print quality, what optimal temperature ranges exist for common materials, how to calibrate temperatures for specific filament brands, what bed temperatures accomplish and how to set them, how cooling rates affect different aspects of prints, what temperature-related problems arise and how to diagnose them, and how environmental temperature influences results. Whether troubleshooting quality issues or seeking to optimize settings for new materials, understanding thermal management principles enables achieving consistent successful results across varying conditions and materials.

How Hotend Temperature Affects Material Flow

The most direct and obvious temperature effect in FDM printing involves how hotend temperature determines whether plastic melts sufficiently to flow through the nozzle at the rates required for printing. Understanding this relationship helps explain numerous print quality issues and guides temperature selection.

Material viscosity changes dramatically with temperature, following exponential relationships where small temperature differences create large fluidity changes. At temperatures below the material’s melting range, plastic remains solid and cannot extrude. As temperature increases into the melting range, the material softens and becomes flowable. Further temperature increases reduce viscosity exponentially, making the plastic progressively more fluid. This means a twenty-degree temperature increase might double or triple flow rate for the same extrusion pressure.

Flow rate requirements depend on print speed and layer geometry, with faster printing or thicker layers demanding higher volumetric throughput. The hotend must melt enough material per second to supply what the print demands. At low temperatures, viscous material cannot flow fast enough even with maximum extrusion pressure, causing under-extrusion. Increasing temperature reduces viscosity, allowing adequate flow. However, excessively high temperatures create problems from material being too fluid.

Extrusion pressure needed to maintain flow decreases as temperature increases. At lower temperatures, the extruder motor must push harder to force viscous material through the nozzle. This increased back-pressure can cause stepper motor skipping where the motor cannot generate sufficient torque and loses steps. Higher temperatures reduce the pressure needed, allowing smooth consistent extrusion. However, too little back-pressure from excessive temperature may allow gravity to pull material out of the nozzle during non-printing moves.

Print speed limits correlate with temperature because maximum speed is constrained by maximum flow rate the hotend can sustain. Printing faster requires either higher temperature to reduce viscosity or accepting under-extrusion. Many users discover they can print faster by increasing temperature ten or twenty degrees, though this trades speed for potential quality issues from the higher temperature. Understanding this relationship helps balance speed desires against temperature implications.

Nozzle diameter affects optimal temperature because larger nozzles require higher flow rates, which benefit from higher temperatures. A 0.8mm nozzle depositing thick wide lines needs more volumetric throughput than a 0.4mm nozzle with standard lines. Increasing temperature five to ten degrees when using larger nozzles often improves flow consistency. Conversely, very small nozzles may print well at slightly reduced temperatures.

Layer height similarly affects flow rate demands, with thicker layers requiring more material per unit length of nozzle travel. The temperature that works for 0.15mm layers might cause under-extrusion at 0.3mm layers if the higher flow rate exceeds what the hotend can deliver at that temperature. Increasing temperature accommodates thicker layers by improving flow capacity.

Material degradation occurs when plastic dwells at excessive temperatures too long, causing chemical breakdown that changes properties and may create fumes. Different materials have different maximum safe temperatures beyond which degradation accelerates. PLA begins degrading noticeably above 230-240°C. ABS tolerates 250-260°C before significant degradation. Understanding degradation limits prevents setting temperatures so high that material quality suffers even if flow improves.

Optimal Temperature Ranges for Common Materials

Different thermoplastic materials have characteristic temperature ranges where they print successfully, though specific optimal temperatures within those ranges depend on formulation details and printer characteristics. Understanding these ranges provides starting points for temperature selection.

PLA (polylactic acid) typically prints between 190-220°C, with most formulations performing well around 200-210°C. PLA has relatively low melting temperature making it easy to print and requiring less energy than high-temperature materials. The material flows readily at these temperatures and cools quickly. Printing at the lower end of the range (190-200°C) reduces stringing and oozing but may cause under-extrusion at higher speeds. The upper end (210-220°C) improves layer bonding and flow but increases stringing tendency.

PETG (polyethylene terephthalate glycol) requires 220-250°C, commonly printing around 235-245°C. PETG needs higher temperatures than PLA due to its different chemistry and higher melting point. The material is sticky when molten, making retraction and stringing management important. Printing at lower PETG temperatures risks under-extrusion and poor layer adhesion. Higher temperatures improve flow and bonding but exacerbate stringing. PETG is less forgiving of temperature errors than PLA.

ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) prints at 230-260°C, typically around 240-250°C. ABS requires high temperatures and benefits from heated enclosures that maintain warm ambient conditions. Lower temperatures cause poor layer bonding and warping. Higher temperatures improve bonding but increase fumes and may cause dimensional accuracy issues. ABS is more challenging than PLA partly due to its high temperature requirements and sensitivity to thermal conditions.

Nylon (polyamide) demands 240-270°C or even higher for some formulations, commonly printing around 250-260°C. Nylon’s high melting point and moisture sensitivity make it challenging. The material must be dried before printing as absorbed moisture causes bubbling and poor quality. High temperatures are essential for adequate flow and layer bonding. Nylon benefits from heated chambers and requires all-metal hotends since PTFE-lined hotends degrade at nylon printing temperatures.

TPU and flexible materials typically print at 210-240°C, varying by specific formulation. These materials are soft and flexible, requiring slow print speeds and often direct drive extruders. Temperature affects both flow characteristics and final part flexibility. Lower temperatures increase firmness while higher temperatures create more flexible parts. Print speed must be very slow regardless of temperature to prevent buckling in the extruder.

Specialty materials including composites, high-temperature plastics, and engineering materials each have specific requirements. Carbon fiber filled filaments often print 10-20°C hotter than their base material. High-temperature materials like polycarbonate may require 270-310°C. Always consult manufacturer specifications as starting points, then fine-tune through testing.

Color variations within the same material base can require different temperatures because pigments and additives affect thermal properties. Black PLA might print optimally at 205°C while white PLA from the same manufacturer prints best at 215°C. Translucent colors often need slightly higher temperatures than opaque colors. This color dependence means temperature optimization is specific to each individual filament spool.

Bed Temperature Effects and Optimization

Build plate temperature serves multiple purposes that affect print success, though its role differs fundamentally from hotend temperature. Understanding what bed heating accomplishes helps optimize this often-overlooked parameter.

First layer adhesion improves dramatically with appropriate bed heating because warm surfaces create better molecular bonding with deposited plastic. When hot plastic contacts a warm bed, the temperature differential is smaller than with a cold bed, allowing more time for the materials to bond before the plastic cools completely. The bed temperature keeps the bottom of the print slightly soft and pliable, improving conformance to surface irregularities and creating stronger adhesion.

Warping prevention represents bed heating’s other primary benefit. Plastic shrinks when cooling from processing temperature to room temperature. This differential contraction creates internal stresses. When the bed is cold, the bottom layer cools rapidly to room temperature while upper layers remain hot, creating large temperature gradients and stress concentrations. Heating the bed maintains the bottom layers at elevated temperature, reducing the thermal differential and the resulting contraction stresses that cause warping.

Material-specific bed temperatures vary based on thermal properties and warping tendency. PLA with low thermal expansion coefficient and minimal warping tendency prints successfully on beds at 50-60°C or even unheated beds with proper surface preparation. PETG benefits from 70-85°C beds. ABS with high thermal expansion requires 90-110°C beds or even higher, combined with enclosures for best results. Nylon typically needs 70-90°C or higher depending on formulation.

Part removal ease inversely correlates with bed temperature because most materials bond more strongly to surfaces when hot but release readily when cooled. This characteristic allows setting bed temperature high during printing for strong adhesion, then allowing cooling before removal for easy release. Some advanced users print the first layers at high bed temperature, then reduce temperature for remaining layers to ease later removal while maintaining early adhesion.

Glass transition temperature of the material determines approximately where bed temperature should target. Glass transition represents the temperature below which amorphous polymers become rigid and above which they remain pliable. Keeping the bed temperature near or slightly above glass transition maintains the bottom layers in a pliable state that resists stress buildup. PLA’s glass transition around 60°C explains why 50-60°C bed temperatures work well.

Heated chamber ambient temperature ideally maintains throughout the build volume for materials prone to warping, but few consumer printers provide active chamber heating. The bed temperature partially heats the chamber through radiant and convective heat transfer. Higher bed temperatures create warmer ambient conditions. Enclosures trap this heat, creating pseudo-chamber heating. For ABS and similar materials, bed temperatures of 100-110°C combined with enclosures approximate active chamber heating effects.

Print surface material affects optimal bed temperature because different surfaces have different thermal properties and temperature tolerances. Glass withstands high temperatures indefinitely. PEI sheets typically tolerate 100-120°C continuous operation. Plastic build surfaces may degrade or deform above certain temperatures. Understanding surface limitations prevents damage when printing high-temperature materials.

Temperature Calibration and Testing

Generic temperature recommendations provide starting points, but optimal settings for specific printer-material combinations require systematic testing. Calibration approaches range from simple observation to structured test prints designed to reveal temperature effects.

Temperature towers print vertical towers with different temperature settings at each level, allowing visual comparison of how different temperatures affect surface quality, stringing, layer adhesion, and other characteristics. The tower starts at one temperature and changes every few layers, stepping through a range like 190-220°C in 5°C increments for PLA. Examining the completed tower reveals which temperature section shows best overall quality, indicating the optimal setting for that material.

Stringing tests specifically evaluate retraction effectiveness at different temperatures. Simple stringing test models create many opportunities for strings to form during travels between disconnected sections. Printing these tests at various temperatures shows how temperature affects oozing tendency. Lower temperatures generally reduce stringing while higher temperatures increase it. The test helps find the highest temperature that still maintains acceptable stringing levels.

Bridging tests reveal how temperature affects cooling and sagging on unsupported horizontal spans. Test models with progressively longer bridges printed at different temperatures show maximum bridgeable distance and surface quality on bridges. Lower temperatures with better cooling typically improve bridging performance, while higher temperatures often cause more sagging. These tests help determine temperature limits for parts with significant bridging requirements.

Overhang tests similarly show how temperature affects performance on angled overhangs approaching the forty-five degree threshold. Test models with surfaces at various angles printed at different temperatures reveal how temperature influences overhang quality. Cooler temperatures usually improve overhangs through better cooling, while hotter temperatures may cause drooping or rough surfaces on challenging angles.

Layer adhesion testing requires evaluating mechanical properties rather than just visual quality. Small test parts printed at different temperatures can be stressed to failure, revealing whether layer bonding is adequate. Parts that easily split along layer lines indicate insufficient temperature for strong bonding. While this destructive testing adds complexity, it reveals whether aesthetic quality comes at the cost of mechanical strength.

Real-time observation during first layer printing provides immediate feedback about temperature appropriateness. Material that flows smoothly without resistance indicates adequate temperature. Material that appears to pull or leave gaps suggests temperature may be too low. Material that spreads excessively or leaves strings suggests temperature may be too high. Experienced users develop intuition for these visual cues that complement structured testing.

Manufacturer recommendations should serve as starting points rather than absolutes. Filament suppliers typically suggest temperature ranges based on their testing, but your specific printer may run hotter or cooler than their test equipment. Environmental factors, print speed, and desired characteristics also justify deviating from manufacturers’ suggestions. Use recommendations to establish initial test ranges, then refine based on actual results.

Common Temperature-Related Problems

Temperature settings outside optimal ranges create characteristic problems that help diagnose whether temperature adjustment would solve issues. Recognizing these patterns enables targeted troubleshooting.

Under-extrusion from insufficient temperature manifests as gaps in top surfaces, incomplete infill, thin weak walls, and generally translucent appearance where solid plastic should exist. The extruder motor may click or skip as it struggles to push plastic through the nozzle against excessive back-pressure. Increasing temperature ten to twenty degrees typically resolves temperature-induced under-extrusion, though mechanical causes like partial clogs must also be considered.

Excessive stringing from high temperature creates thin plastic threads between separate sections of prints where travels occurred. The strings form because hot fluid plastic oozes from the nozzle during non-printing moves despite retraction. Reducing temperature by five to fifteen degrees usually reduces stringing significantly. However, retraction settings, travel speed, and material characteristics also affect stringing, so temperature alone may not completely eliminate strings.

Poor layer adhesion causing parts to split along layer lines indicates insufficient heat for adequate thermal bonding between layers. The previous layer cools too much before the next layer deposits, reducing heat available for molecular diffusion across the boundary. Increasing temperature improves bonding by keeping layers warmer during critical bonding moments. Ten to twenty degree increases often transform weak parts into strong ones.

Oozing and blobbing from excessive temperature occurs when material is so fluid it drips or leaks from the nozzle uncontrollably. Blobs appear on surfaces where the nozzle pauses. Oozing creates defects where the nozzle moves to start new features. Reducing temperature makes material more viscous, reducing unwanted flow. Five to ten degree reductions often suffice to control oozing while maintaining adequate flow for printing.

Warping despite proper bed adhesion sometimes results from excessive temperature differential between hotend and bed or ambient. When very hot material deposits onto a relatively cool bed, the large temperature swing creates internal stresses. Increasing bed temperature reduces this differential. For extremely warp-prone materials, reducing hotend temperature slightly while increasing bed temperature balances the thermal system better.

Clogging from heat creep occurs when heat migrates up the hotend farther than intended, softening filament prematurely in the cold zone. The soft filament jams against the tube rather than sliding smoothly through. This manifests as intermittent extrusion followed by complete blockage. The problem stems from insufficient cooling on the cold end rather than hotend temperature directly, but reducing temperature slightly can sometimes help as a temporary measure.

Dimensional inaccuracy from thermal expansion affects precision when very high temperatures cause excessive material expansion. The deposited plastic is significantly larger when hot than when cooled to room temperature. Excessive hotend temperature exacerbates this effect. Reducing temperature minimizes thermal expansion, improving dimensional accuracy at the cost of potentially reduced flow and layer bonding.

Conclusion

Temperature control represents one of the foundational elements determining success in three-dimensional printing, affecting material flow through the nozzle, layer bonding strength, warping tendency, and numerous quality characteristics. Understanding how temperature influences each aspect of printing enables optimization that balances competing requirements.

The hotend temperature primarily determines whether material flows adequately for the demanded extrusion rate. Too low causes under-extrusion and poor layer bonding. Too high creates stringing, oozing, and potential dimensional issues. Finding the sweet spot requires testing specific material-printer combinations rather than blindly applying generic recommendations.

Bed temperature improves first layer adhesion and reduces warping by maintaining elevated temperature at the base of prints. Different materials require vastly different bed temperatures based on their thermal properties and warping tendencies. Optimizing bed temperature involves balancing strong adhesion during printing against easy release after cooling.

Temperature calibration through structured testing reveals optimal settings for specific situations. Temperature towers, stringing tests, bridging evaluations, and real-world observation all contribute to finding settings that work for your equipment, materials, and quality requirements. Generic recommendations provide starting points, but optimal temperatures emerge through systematic testing.

Common temperature-related problems each have characteristic symptoms that indicate whether temperature adjustment would help. Under-extrusion, excessive stringing, poor layer adhesion, and warping all connect to temperature settings. Recognizing these patterns enables targeted troubleshooting rather than random parameter changes.

Mastering temperature control transforms printing from an unpredictable process to a controlled one where material behavior becomes understandable and manageable. The investment in learning how temperature affects results and determining optimal settings for your specific combination of equipment and materials pays dividends in improved success rates, better quality, and reduced frustration from temperature-related failures.