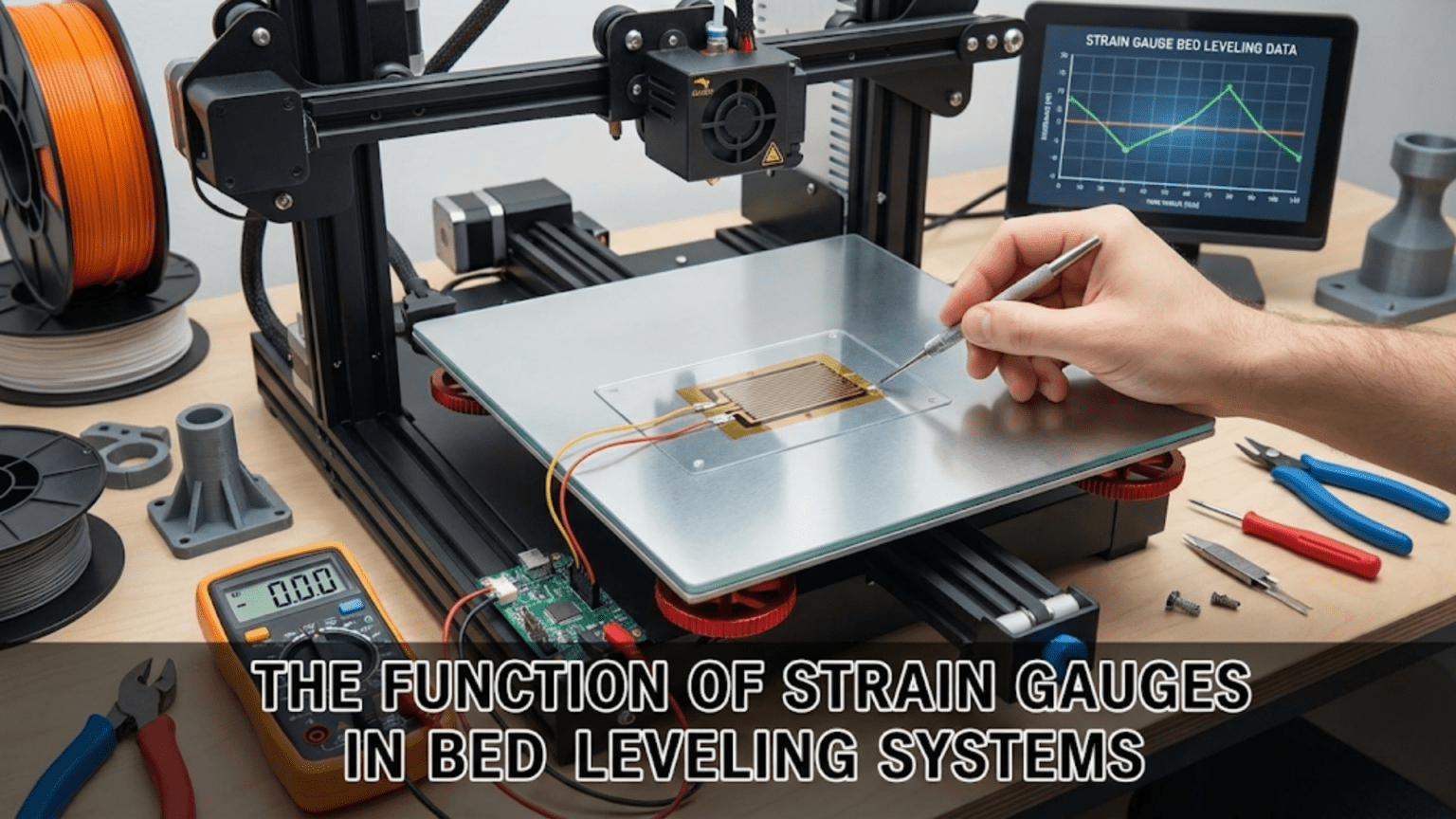

Strain gauges in bed leveling systems measure the tiny forces created when the nozzle contacts the bed surface, effectively using the nozzle itself as the probe and eliminating the need for separate probe sensors. These systems work by mounting the nozzle or entire toolhead on strain-sensitive load cells or piezoelectric sensors that detect the deflection or force when the nozzle touches the bed, with firmware interpreting these signals to determine the exact Z-height at each probe point, enabling accurate bed leveling without additional probing hardware while ensuring measurements occur at the exact nozzle position rather than an offset probe location.

Introduction

Traditional bed leveling probes—BLTouch sensors, inductive probes, capacitive sensors—all share a common limitation: they measure bed height at a location offset from the nozzle. While firmware compensates for this offset, it introduces potential error sources. The probe might trigger on a different surface than where the nozzle will actually print. Temperature differences between probing and printing can shift the relationship. Any probe offset misconfiguration translates directly to first layer problems.

Strain gauge systems take a radically different approach: use the nozzle itself as the probe. By measuring the forces created when the nozzle touches the bed, these systems detect contact with perfect accuracy—no offset, no calibration of probe-to-nozzle distance, and measurements at the exact location where plastic will be deposited. This elegant solution eliminates multiple error sources while simplifying the mechanical design.

Yet strain gauge leveling remains less common than traditional probes, appearing primarily in higher-end or custom-built printers. Understanding how these systems work—the physics of strain gauges, the mechanics of force measurement, and the firmware integration making it useful—reveals both their advantages and why they haven’t completely displaced traditional probing methods.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore strain gauge bed leveling from fundamental principles through practical implementation, understanding what makes these systems special and when they offer genuine advantages over conventional probes.

What Are Strain Gauges?

Before examining their bed leveling application, understanding the basic technology:

Strain Gauge Fundamentals

Definition: A strain gauge is a sensor that measures deformation (strain) by detecting changes in electrical resistance.

Construction:

- Very thin metal foil arranged in a grid pattern

- Bonded to a flexible backing material

- Applied to surfaces that will deform under load

- Lead wires connect to measurement electronics

Operating Principle:

- When the material deforms, the metal foil stretches or compresses

- Stretching increases resistance (longer, thinner conductor)

- Compression decreases resistance (shorter, thicker conductor)

- Resistance change is proportional to strain

- Electronics measure this resistance change

Sensitivity:

- Extremely sensitive to tiny deformations

- Can detect micrometers of deflection

- Typical resistance: 120-350 ohms

- Resistance change: 0.1-0.5% per 1000 microstrain

- Requires precision measurement electronics

Wheatstone Bridge Circuit

Strain gauges typically connect in a Wheatstone bridge configuration:

Circuit Function:

- Four resistors arranged in a bridge

- One or more are strain gauges

- Bridge balanced when unstrained (zero output)

- Strain creates imbalance, producing voltage output

- Output voltage proportional to strain

Temperature Compensation:

- Temperature affects resistance similar to strain

- Bridge configuration cancels temperature effects

- Multiple gauges in bridge compensate each other

- Improves measurement accuracy

Signal Amplification:

- Bridge output very small (millivolts)

- Requires amplification for useful measurement

- Dedicated instrumentation amplifiers used

- Often integrated in strain gauge signal conditioners

Strain Gauges in Bed Leveling

Several implementations use strain measurement for leveling:

Nozzle-as-Probe Systems

The most elegant approach mounts the hotend on strain-sensitive supports:

Mechanical Design:

- Hotend mounted on flexible element

- Strain gauges bonded to flexible element

- Entire hotend can deflect slightly

- Contact with bed creates measurable deflection

Operation:

- Z-axis lowers nozzle toward bed

- Nozzle contacts bed surface

- Contact force causes hotend deflection

- Strain gauges detect deflection

- Signal exceeds threshold, firmware recognizes contact

- Z-height recorded at this point

Advantages:

- No probe offset (nozzle IS the probe)

- Measures exactly where printing occurs

- Works with any bed surface

- No deployment/retraction delays

- One less component to maintain

Challenges:

- Mechanical complexity in hotend mounting

- Electronics must handle noise and temperature

- Calibration sensitivity critical

- Potential for false triggers from vibration

Piezoelectric Force Sensors

An alternative uses piezo sensors instead of strain gauges:

Piezoelectric Effect:

- Certain crystals generate voltage when mechanically stressed

- No external power needed for sensing

- Very fast response time

- Sensitive to force/pressure

Implementation:

- Piezo disks or washers under hotend mounting

- Nozzle contact creates force on piezo

- Voltage spike indicates contact

- Electronics detect voltage threshold

Characteristics:

- Simpler than full strain gauge bridges

- Lower cost implementation

- May be less stable over temperature

- Typically requires AC-coupled signal processing

Load Cell Based Systems

Some systems use complete load cells:

Load Cell Design:

- Commercial load cells with integrated strain gauges

- Designed specifically for force measurement

- Incorporate compensation and protection

- Available in various force ranges

Application:

- Hotend or entire carriage mounted on load cells

- Very precise force measurement

- Professional-grade accuracy possible

- More expensive than discrete strain gauges

Implementation Architectures

Different mechanical approaches to strain gauge leveling:

Three-Point Mount Design

Configuration:

- Hotend mounted on three points

- Each with strain-sensitive element

- Triangle configuration provides stability

- Averaging three measurements improves accuracy

Benefits:

- Redundancy improves reliability

- Can detect non-perpendicular contact

- Better noise rejection

- Identifies mounting problems

Complexity:

- Three separate sensor channels

- More complex signal processing

- Higher cost

- More difficult calibration

Single Strain-Sensitive Mount

Simpler Approach:

- Hotend on single flexible element

- One or two strain gauges measure deflection

- Lower cost and complexity

- Adequate for many applications

Tradeoffs:

- Less redundancy

- More sensitive to mechanical variations

- Adequate accuracy for most users

- Easier implementation

Bed-Mounted Strain Sensors

Alternative Configuration:

- Strain gauges on bed mounting instead of hotend

- Bed deflects slightly when nozzle contacts

- Detects force transmitted through bed

- Less common implementation

Considerations:

- Large bed mass reduces sensitivity

- Thermal effects from bed heating

- Mounting point strain may be inconsistent

- Generally less practical than hotend mounting

Signal Processing and Electronics

Converting strain gauge signals to usable bed leveling data:

Amplification and Conditioning

Signal Chain:

- Strain gauge bridge produces millivolt signals

- Instrumentation amplifier boosts to volt-level

- Filtering removes noise and vibration

- Analog-to-digital conversion creates digital signal

- Microcontroller processes digital values

Noise Challenges:

- Mechanical vibration creates noise

- Electromagnetic interference from steppers/heaters

- Thermal drift from temperature changes

- Ground loops in wiring

Filtering Strategies:

- Low-pass filtering removes high-frequency noise

- Averaging multiple samples improves signal-to-noise

- Threshold detection ignores small fluctuations

- Software filtering complements hardware

Threshold Detection

Triggering Logic:

- Firmware monitors strain signal continuously

- Compares to configured threshold

- Signal exceeding threshold indicates contact

- Must distinguish real contact from noise

Threshold Setting:

- Too low: False triggers from vibration or noise

- Too high: Excessive force on bed, delayed detection

- Optimal: Just above noise floor, quick detection

- May require calibration for specific printer

Temperature Compensation

Thermal Effects:

- Strain gauges sensitive to temperature

- Hotend heating changes baseline reading

- Bed heating affects measurements

- Ambient temperature variations matter

Compensation Methods:

- Wheatstone bridge configuration cancels some effects

- Reference measurements at known temperatures

- Software compensation based on temperature sensors

- Thermal stabilization before probing

Firmware Integration

Strain gauge systems require firmware support:

Marlin Support

Configuration: Some experimental Marlin forks support strain gauges, but not in standard Marlin as of most recent stable releases.

Implementation Concepts:

- Analog pin reads strain gauge signal

- Threshold value defines contact

- Z-movement stops on trigger

- Standard bed leveling mesh code applies

Klipper Support

More Flexible Architecture: Klipper’s design better accommodates custom sensors:

Configuration Example (conceptual):

[strain_gauge_probe]

sensor_pin: analog11

threshold: 2.5

sample_count: 5

sample_tolerance: 0.02Features:

- Custom sensor definitions possible

- Signal processing in host computer

- Advanced filtering and averaging

- Calibration routines

RepRapFirmware

Duet Boards:

- Some support for force-sensing probes

- Configuration through config.g

- Threshold and sensitivity adjustable

- Good documentation for supported systems

Advantages of Strain Gauge Leveling

Understanding the benefits:

Zero Probe Offset

Perfect Alignment:

- Nozzle itself makes contact

- No X/Y offset to configure

- No probe-to-nozzle distance errors

- Measurements exactly where printing occurs

Simplified Configuration:

- Eliminates probe offset calibration

- One less potential error source

- Easier for beginners to set up correctly

- No offset drift over time

Surface Independence

Universal Compatibility:

- Works with metal, glass, PEI, BuildTak, anything

- No surface-specific calibration

- No sensing distance variations

- Consistent across different bed materials

Flexibility:

- Change bed surfaces without reconfiguration

- Multi-surface users benefit greatly

- Experimenting with surfaces simplified

Accurate Z-Height

Direct Measurement:

- Nozzle contact is definitive

- No interpretation of trigger distance

- Thermal expansion doesn’t affect offset

- True nozzle-to-bed distance measured

Challenges and Limitations

Understanding the drawbacks:

Mechanical Complexity

Implementation Difficulty:

- Requires specialized hotend mounting

- Flexible elements must allow deflection but maintain rigidity

- More complex than adding external probe

- DIY implementation challenging

Potential Failure Modes:

- Strain gauge damage from excessive force

- Mechanical mounting degradation

- Signal wire fatigue from flexing

- Requires careful design and assembly

Electrical Noise

Noisy Environment:

- 3D printers generate significant electromagnetic interference

- Stepper motors create pulses

- Heater switching adds noise

- Long signal wires act as antennas

Signal Quality:

- Requires good shielding and grounding

- Filtering necessary but can slow response

- Balancing noise rejection with sensitivity

- More electrically complex than simple switches

Calibration Sensitivity

Threshold Adjustment:

- Must be set precisely

- Too sensitive: false triggers

- Too insensitive: excessive force or missed detection

- May require adjustment for different conditions

Environmental Factors:

- Temperature affects calibration

- Vibration from floor/building

- Electrical noise varies by environment

- May need periodic recalibration

Cost and Availability

Commercial Systems:

- Strain gauge bed leveling not in most consumer printers

- Limited commercial availability

- Higher cost than traditional probes

- Less community support and documentation

DIY Challenges:

- Requires understanding of strain gauges

- Electronics knowledge necessary

- Mechanical fabrication skills needed

- Troubleshooting more complex

Strain Gauge vs Traditional Probe Comparison

| Feature | Strain Gauge System | BLTouch Probe | Inductive Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe Offset | None (nozzle is probe) | X/Y offset needs configuration | X/Y offset needs configuration |

| Surface Compatibility | Any surface | Any surface | Metal only |

| Accuracy | Excellent (direct nozzle contact) | Excellent | Good |

| Speed | Fast (instant contact detection) | Moderate (deploy/retract delays) | Fast |

| Mechanical Complexity | High | Moderate | Low |

| Electrical Complexity | High | Moderate | Low |

| Cost | High (DIY) to Very High (commercial) | Moderate | Low |

| Availability | Limited | Widely available | Widely available |

| Reliability | Good (when properly implemented) | Good | Excellent |

| Maintenance | Moderate | Moderate (mechanical parts) | Low |

Practical Implementations

Examples of strain gauge leveling in real systems:

Prusa MK4 and XL

Load Cell System:

- Prusa’s newer printers use load cell based leveling

- Nextruder design incorporates force sensing

- Commercial implementation proving viability

- Demonstrates mainstream adoption potential

Benefits Realized:

- Simplified user experience

- Excellent first layer consistency

- No probe offset configuration needed

- Proves concept for consumer applications

DIY Implementations

Community Projects:

- Various open-source designs exist

- Often using piezo sensors for lower cost

- Sharing calibration and configuration information

- Advancing the technology accessibility

Common Approaches:

- Piezo disks under hotend mounting screws

- Strain gauges on flexible mounting plates

- Load cells in custom carriages

- Mix of mechanical and electronic solutions

Future of Strain Gauge Leveling

Technology development directions:

Increasing Adoption

Trends:

- More manufacturers exploring implementation

- Prusa adoption encouraging others

- Patents expiring enabling broader use

- Technology maturity improving reliability

Barriers Decreasing:

- Electronics becoming cheaper and more integrated

- Designs being refined and shared

- Firmware support improving

- Documentation and knowledge growing

Enhanced Features

Beyond Basic Leveling:

- First layer pressure monitoring

- Nozzle crash detection

- Automatic flow rate adjustment based on resistance

- Build surface characterization

Integration Opportunities:

- Combined with other sensors

- Part of larger quality control systems

- Enabling new capabilities beyond current probes

Troubleshooting Strain Gauge Systems

Common issues and solutions:

False Triggers

Symptoms: Probe triggers before nozzle contacts bed.

Causes:

- Threshold set too low

- Excessive electrical noise

- Mechanical vibration sensitivity

- Ground loop issues

Solutions:

- Increase threshold slightly

- Improve shielding and grounding

- Add vibration damping

- Filter signal more aggressively

Missed Contacts

Symptoms: Nozzle contacts bed but probe doesn’t trigger.

Causes:

- Threshold too high

- Signal conditioning inadequate

- Strain gauge damage

- Poor electrical connections

Solutions:

- Decrease threshold

- Check and improve signal amplification

- Test strain gauge resistance

- Verify all connections secure

Inconsistent Measurements

Symptoms: Repeated probing shows significant variation.

Causes:

- Temperature effects

- Mechanical instability

- Electrical noise

- Surface inconsistency

Solutions:

- Allow thermal stabilization

- Improve mechanical rigidity

- Enhance noise filtering

- Ensure clean, flat probing surface

Conclusion

Strain gauge bed leveling represents an elegant solution to the probe offset problem, using the nozzle itself as the sensing element through force measurement rather than separate probe sensors. By detecting the tiny deflections or forces created when the nozzle touches the bed, these systems achieve perfect alignment between probing and printing locations while working with any bed surface material.

The advantages are compelling: zero probe offset eliminates a major configuration and error source, universal surface compatibility means changing bed materials requires no recalibration, and direct nozzle contact provides the most accurate possible Z-height measurement. These benefits explain why manufacturers like Prusa have adopted the technology in their latest printers.

Yet the challenges are real: mechanical complexity in implementation, electrical noise sensitivity requiring careful signal processing, and calibration demands that exceed simple probe installation. The higher cost and limited availability compared to traditional probes means strain gauge systems remain primarily in higher-end printers or sophisticated DIY builds.

As the technology matures, costs decrease, and adoption increases, strain gauge leveling may eventually displace traditional probes in many applications. The fundamental advantages of probe-less bed leveling—measuring exactly where you print, with what you print—make it attractive enough that the current limitations likely represent temporary obstacles rather than permanent barriers.

The next time you see a printer probing the bed with its nozzle rather than a separate sensor, appreciate the sophisticated strain measurement happening in that instant of contact. Those tiny deflections detected by strain gauges or piezo sensors represent the cutting edge of bed leveling technology, pointing toward a future where probe offsets and calibration complexities become relics of an earlier era.