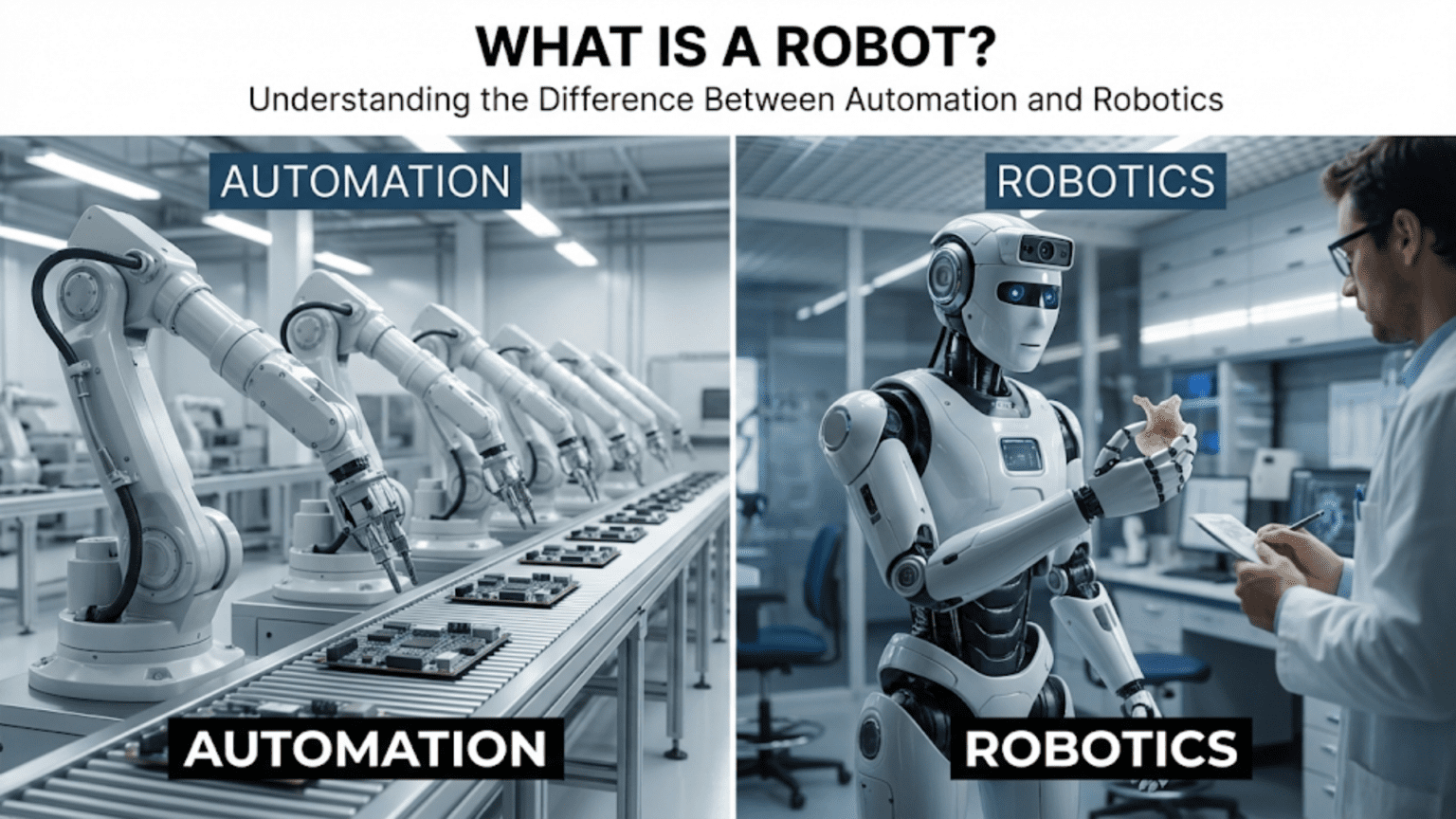

You have probably encountered the word “robot” hundreds of times throughout your life, from science fiction movies to news articles about manufacturing. Yet if someone asked you to define exactly what makes something a robot rather than just an automated machine, you might find the answer more challenging than expected. This question sits at the heart of understanding robotics as a field, and getting clarity on it will shape how you think about every robot you encounter or build in the future.

The confusion is understandable because our world is filled with automated systems that perform tasks without human intervention, yet we do not call all of them robots. Your washing machine runs through cycles automatically, your thermostat adjusts your home temperature without your constant input, and your car’s cruise control maintains your speed on the highway. None of these typically earn the label of “robot” in everyday conversation, even though they operate autonomously to some degree. So what separates a robot from these other automated devices?

The Core Definition of a Robot

A robot is a programmable machine that can sense its environment, make decisions based on that sensory information, and then act upon the world around it to accomplish specific tasks. Notice that this definition contains three essential components that must work together. The robot must be able to perceive what is happening in its surroundings through sensors, process that information to make decisions, and then execute physical actions through actuators. All three elements need to be present for us to truly call something a robot.

Think about this definition in comparison to simpler automated systems. Your washing machine certainly acts on the world by spinning clothes and spraying water, and it makes decisions based on the cycle you select and the timer that counts down. However, it does not genuinely sense its environment beyond the most basic level. It cannot tell if your clothes are actually clean or adjust its behavior based on how dirty they are. It simply follows a predetermined sequence of actions. This lack of environmental sensing and adaptive behavior places it firmly in the category of automation rather than robotics.

The programmability aspect of the definition is equally important. A robot should be able to be reprogrammed to perform different tasks or modify its behavior based on new instructions. This flexibility distinguishes robots from fixed automation systems that can only ever perform one specific sequence of actions. Even if a machine has sensors and actuators, if it cannot be reprogrammed to change its behavior, it falls short of being a true robot.

Sensing the Environment

The sensing capability represents the robot’s ability to gather information about the world around it. This might happen through cameras that provide visual information, ultrasonic sensors that measure distances to nearby objects, touch sensors that detect physical contact, temperature sensors that monitor heat, or dozens of other types of sensors. The key point is that the robot actively collects data about conditions that exist outside of itself.

This sensing capability allows robots to handle uncertainty and variation in their environment. Imagine a robot designed to pick up objects from a table. If the objects are always placed in exactly the same position every single time, the robot would not actually need sensors at all. It could simply be programmed to move to that precise location and close its gripper. However, in the real world, objects appear in different positions, have different shapes, and exist in different lighting conditions. A true robot uses its sensors to find the object wherever it happens to be, adapting its actions accordingly.

The quality and variety of sensors often determine what tasks a robot can accomplish. A robot with only basic touch sensors might be able to detect when it bumps into a wall but cannot navigate around obstacles it has not yet touched. Adding distance sensors like ultrasonic or infrared sensors allows it to detect obstacles before collision. Including a camera expands its capabilities even further, enabling it to recognize specific objects, read text, or follow colored lines on the floor. As you progress in robotics, you will discover that selecting the right sensors for your intended task is one of the most important design decisions you will make.

Making Decisions

The decision-making component is what we often call the robot’s “brain,” though this brain works quite differently from biological brains in most cases. At its core, this component processes the information coming from sensors and determines what actions the robot should take in response. This processing happens through a computer program running on a microcontroller, microprocessor, or more powerful computer, depending on the complexity of the robot.

The sophistication of this decision-making varies enormously across different robots. At the simpler end, a robot might use straightforward rules such as “if the distance sensor reads less than ten centimeters, then turn left.” This type of reactive behavior allows the robot to respond to its immediate sensory input without complex reasoning. Despite its simplicity, this approach can produce surprisingly effective behavior, especially when multiple simple rules work together.

More advanced robots employ sophisticated algorithms that allow them to plan sequences of actions, predict future states of their environment, or even learn from experience. A robot vacuum cleaner, for instance, might build a map of your home as it cleans, allowing it to plan efficient paths and remember which areas it has already covered. Industrial robot arms calculate complex mathematical equations to determine the precise angles needed for each joint to position their end effector exactly where it needs to be. The most advanced robots today incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning, enabling them to recognize objects they have never seen before or adapt their behavior based on past successes and failures.

What matters at this foundational level is understanding that robots make decisions based on information rather than simply following a fixed, unchanging sequence. The robot evaluates its current situation through its sensors and determines appropriate actions based on that evaluation. This responsive behavior is what allows robots to function in real-world environments that are never exactly the same twice.

Acting on the World

The third essential component involves the robot’s ability to physically affect its environment through actuators. These are the motors, pistons, grippers, wheels, legs, or other mechanical systems that allow the robot to move itself or manipulate objects around it. Without this physical action capability, you would simply have a sensor system that observes but cannot change anything.

Actuators translate the electrical signals from the robot’s computer brain into mechanical motion. When the robot’s program decides that it should move forward, turn right, or grasp an object, actuators make those actions happen in the physical world. The types of actuators a robot uses depend entirely on what tasks it needs to accomplish. A mobile robot exploring an environment needs actuators that provide locomotion, such as wheels, tracks, or legs. A robot arm in a factory needs rotational joints powered by motors that can position tools precisely. A gripper needs actuators that can open and close with controlled force to pick up objects without dropping or crushing them.

The relationship between sensing, deciding, and acting creates what engineers call a feedback loop or control loop. The robot senses its environment, decides on an action, performs that action through its actuators, and then senses the environment again to see what effect its action had. This continuous cycle allows robots to accomplish complex tasks even when things do not go exactly as planned. If a robot reaches for an object and its sensors detect that it missed, it can adjust its position and try again. This ability to perceive the results of its own actions and make corrections is fundamental to how robots operate.

Why the Distinction Matters

Understanding what truly makes something a robot rather than simple automation might seem like an academic exercise, but this distinction has practical importance. When you begin designing or building your own robotic systems, recognizing these three core components helps you think clearly about what your robot needs. You will ask yourself questions like “What does my robot need to sense?”, “What decisions will it need to make?”, and “What physical actions must it perform?” These questions naturally guide your design process toward a functional robot.

The distinction also helps you set realistic expectations about what different systems can accomplish. Automated systems that lack sensing capabilities cannot adapt to changing conditions. They work wonderfully when everything happens exactly as expected but fail when faced with variation or unexpected situations. True robots, with their ability to sense and respond, can handle much more complex and variable real-world environments. However, this capability comes with increased complexity in both hardware and programming.

As you explore robotics further, you will encounter systems that blur the lines of these definitions. Some automated systems incorporate limited sensing to enhance their operation without becoming fully autonomous robots. Some robots operate with such sophisticated artificial intelligence that they seem to make decisions in ways that go far beyond simple programmed rules. The field of robotics continues to evolve, and the boundaries between automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence become increasingly interconnected. However, understanding the fundamental principles of sensing, deciding, and acting provides you with a solid foundation for making sense of these more advanced concepts as you encounter them.

Looking Forward

Now that you understand what defines a robot at its most fundamental level, you are prepared to explore the fascinating diversity of robotic systems that exist in our world. Some robots look humanoid with heads, arms, and legs, while others appear as wheeled platforms, flying drones, or stationary arms. Some work autonomously for hours without human oversight, while others require constant human guidance to accomplish their tasks. Despite this incredible variety, all true robots share those three core capabilities of sensing, deciding, and acting.

As you continue your journey into robotics, you will discover how engineers and researchers combine these basic elements in creative ways to solve real problems. You will learn about the specific types of sensors robots use to perceive different aspects of their environment, the programming techniques that enable robots to make intelligent decisions, and the mechanical systems that allow robots to move and manipulate objects. Each of these topics builds upon this foundational understanding of what makes a machine a robot rather than just another automated device.

The field of robotics sits at the intersection of mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and computer science, drawing on insights from all three disciplines. This interdisciplinary nature makes robotics both challenging and exciting. Whether your background lies in programming, electronics, mechanical design, or you are approaching the field with fresh eyes and curiosity, there is a place for you in robotics. The most important step is developing a clear understanding of the fundamentals, which you have now begun with this foundational knowledge of what a robot truly is.