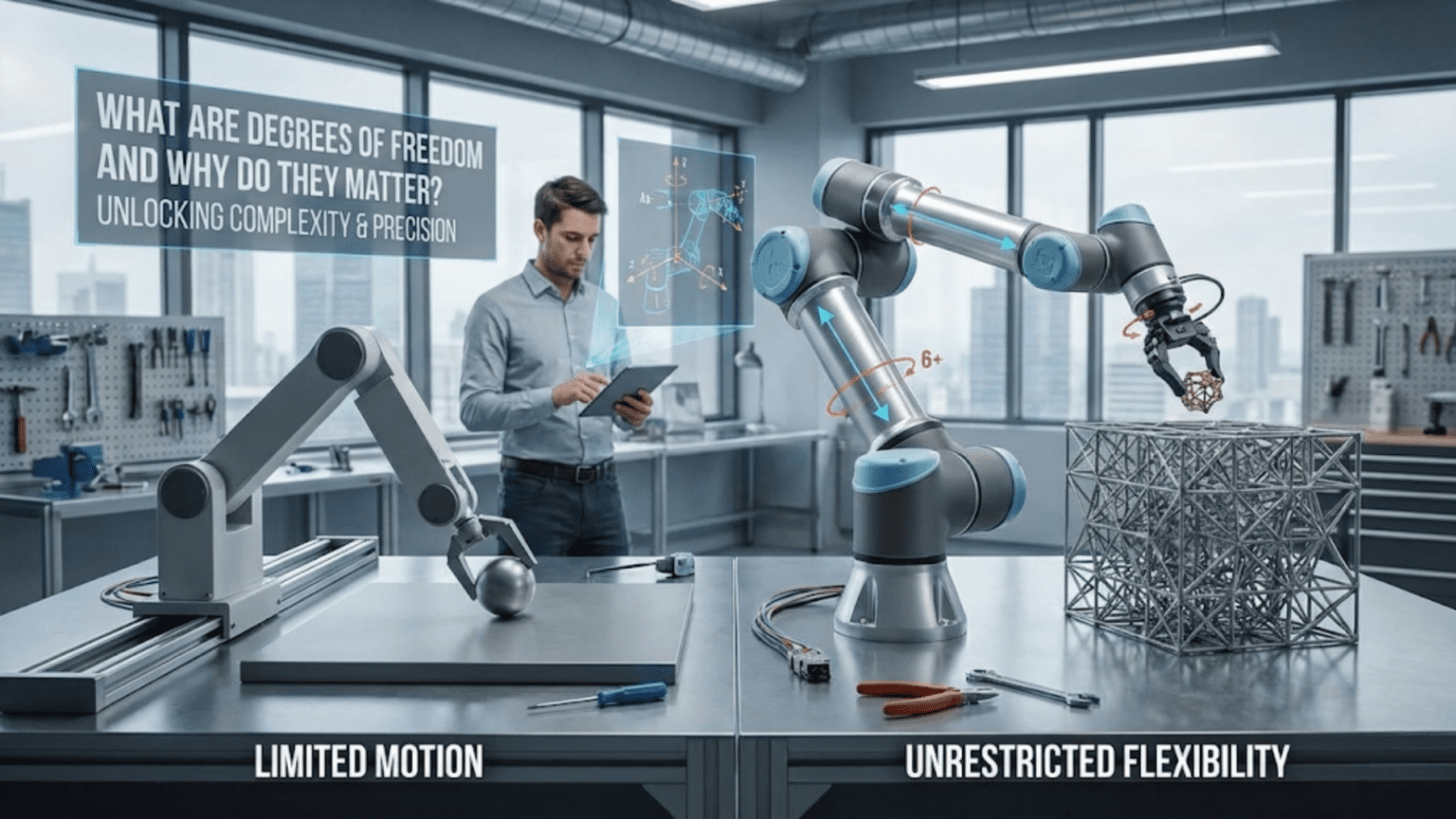

When roboticists describe robots, one specification appears consistently across technical documentation and casual conversation alike: degrees of freedom, commonly abbreviated as DOF. You might hear that an industrial robot has six degrees of freedom, a simple arm has two, or a humanoid robot has dozens. These numbers capture something fundamental about robot capability, yet the concept remains mysterious to many beginners. What exactly is a degree of freedom? Why do more degrees always seem better? And how do these abstract mathematical concepts translate into practical differences in what robots can accomplish?

Understanding degrees of freedom transforms how you think about robot design, capability, and limitations. This concept directly determines whether a robot can reach all positions and orientations within its workspace, perform certain tasks, or requires compromises in how it operates. A robot with insufficient degrees of freedom for its intended task will fail no matter how sophisticated its control algorithms or sensors become. Conversely, excess degrees of freedom create control complexity without corresponding capability gains. The number and arrangement of degrees of freedom fundamentally shape what a robot can and cannot do.

This article builds your intuitive understanding of degrees of freedom from fundamental concepts through practical robotics applications. You will learn what degrees of freedom represent physically, how to count them in actual robots, why certain numbers of degrees appear repeatedly in robot designs, and how degrees of freedom constraints affect robot capabilities. Rather than drowning in mathematical formalism, this exploration emphasizes geometric intuition and practical understanding that helps you design robots, evaluate robot specifications, and appreciate why degrees of freedom matter so profoundly in robotics.

The Fundamental Concept: Independent Motions

At its core, a degree of freedom represents an independent way something can move. Understanding this independence concept provides the foundation for everything else about degrees of freedom.

Imagine you are standing in an empty room. You can move forward or backward along a straight line. That represents one degree of freedom, a single independent direction of motion. Now recognize you can also move left or right, perpendicular to your forward-backward motion. That represents a second degree of freedom, another independent direction. Finally, you can move up or down by jumping or crouching. That third independent direction gives you three degrees of freedom for position in three-dimensional space.

The critical word here is independent. Moving forward does not automatically cause you to move left or up. Each direction represents a separate choice you can make independently of the others. You could move forward without moving left. You could move both forward and left simultaneously, with the amount you move in each direction being independent choices. This independence means the three positional degrees of freedom are truly separate capabilities rather than aspects of a single motion type.

Now consider rotation. Even if you stay in one position without translating, you can rotate your body. You can turn left or right around a vertical axis, which represents one rotational degree of freedom. You can tilt forward or backward around a horizontal axis, giving you a second rotational degree of freedom. You can roll your shoulders so one rises while the other falls, rotating around the forward-backward axis for a third rotational degree of freedom. These three rotational freedoms are independent of each other and independent of your three translational freedoms.

Combining positional and rotational freedoms, you as a human body in space possess six degrees of freedom for your overall position and orientation. You have three translational degrees of freedom determining where you are in space, plus three rotational degrees of freedom determining how you are oriented. This six-degree-of-freedom description completely specifies your pose, which is the combination of position and orientation. Nothing about your location or orientation remains unspecified once all six degrees of freedom are determined.

This six-DOF structure for describing pose in three-dimensional space proves universal. Any rigid object floating in space, unconstrained by connections to other objects, has six degrees of freedom. A spacecraft tumbling through vacuum has six degrees of freedom. A drone hovering in air has six degrees of freedom. A rigid object placed on a table has fewer degrees of freedom because the table constrains some motions, but a truly free rigid body always has exactly six.

Understanding that degrees of freedom count independent motion capabilities helps you analyze any mechanical system. Each independent motion represents another dimension of freedom the system possesses. Constraining a degree of freedom removes one independent motion capability. Adding a degree of freedom enables motion previously impossible. This counting of independent motions provides the mathematical and physical substance behind the degrees of freedom concept.

Degrees of Freedom in Simple Mechanisms

Before tackling complete robots, examining simple mechanisms shows how degrees of freedom manifest in physical systems and how constraints reduce freedom.

A door hinged on one side demonstrates a single degree of freedom. The door can swing open at various angles, but that angle is the only thing you can change. The hinge constrains all other motions. The door cannot move up, down, left, or right. It cannot tilt at odd angles or spin around any axis except the hinge axis. All the door can do is rotate around that single hinge axis, giving it one degree of freedom. This single-DOF mechanism represents the simplest type of controllable motion.

A drawer sliding in and out of a desk similarly has one degree of freedom, though translational rather than rotational. The drawer can extend or retract, but the rails constrain it to that single straight-line motion. It cannot move side to side, tilt, or rotate. The single DOF completely describes the drawer’s configuration, just as a single angle completely describes a hinged door’s configuration.

A computer mouse on a mousepad has two degrees of freedom for position. It can move forward-backward and left-right across the two-dimensional surface. The mouse cannot move up (the desk prevents that), cannot tilt significantly (friction and gravity constrain orientation), and its rotation around the vertical axis usually does not matter for basic mouse operation. Those constraints reduce the mouse’s six potential degrees of freedom down to two translational degrees actually available and useful.

A ceiling fan with pull chains illustrates distinct degrees of freedom with different actuators. One chain controls fan speed, representing one degree of freedom. Another chain controls light brightness, representing another degree of freedom. These degrees of freedom are completely independent—changing fan speed does not affect light brightness and vice versa. You can set them to any combination of values independently. Physical mechanisms often have multiple separate actuators providing independent degrees of freedom exactly like this.

These simple examples establish important principles. Constraints reduce degrees of freedom by eliminating certain motions. Physical connections like hinges, rails, or surfaces restrict how objects can move. The number of degrees of freedom equals the number of independent position or orientation values you need to completely specify the system’s configuration. Simple mechanisms with few degrees of freedom build intuition for understanding more complex robotic systems.

Degrees of Freedom in Robot Arms

Robot manipulators provide the clearest examples of how degrees of freedom determine capability. The number and arrangement of joints directly determines what the arm can accomplish.

A single-joint arm rotating around a vertical axis demonstrates one degree of freedom. This simple arm can swing objects in a circle at constant radius and height. The single degree of freedom limits the arm dramatically. It cannot reach objects at different distances from its base. It cannot reach higher or lower. All it can do is rotate around that axis, sweeping through a circular path at fixed height and radius. While this single-DOF arm could be useful for rotating objects to different angular positions, its workspace limitation reveals why single-DOF arms rarely solve practical manipulation problems.

Adding a second joint that extends the arm radially creates a two-degree-of-freedom arm that can reach any position in a horizontal plane. The first joint determines angle, the second joint determines radius. Together, these two joints enable reaching any position in the circle at base height. This two-DOF arm represents substantial improvement over the one-DOF version, accessing a planar workspace instead of a circular arc. However, it still cannot reach objects at different heights. The arm remains confined to a horizontal plane by its two-DOF constraint.

A three-degree-of-freedom arm adding vertical reach can position its end-effector at any point in three-dimensional space within its maximum reach radius. These three DOF might be vertical rotation, vertical angle, and extension, or various other joint arrangements providing three independent motions. Three DOF suffice for reaching any position in the workspace. However, three-DOF arms cannot orient the end-effector arbitrarily. The gripper arrives at target positions with whatever orientation results from the joint angles that got it there. For some applications, this orientation limitation proves acceptable. For others, it becomes a critical constraint.

Six-degree-of-freedom arms can reach any position within their workspace while orienting the end-effector at any desired angle. Three DOF control position (where the end-effector is), and three additional DOF control orientation (how the end-effector is rotated). Six DOF provides complete control over end-effector pose in three dimensions. Industrial robot arms commonly feature six DOF for exactly this reason. Six DOF enables positioning and orienting tools or grasped objects arbitrarily within the workspace, providing maximum manipulation flexibility.

Seven or more degrees of freedom in manipulators creates redundancy where multiple joint configurations achieve the same end-effector pose. This redundancy provides advantages including obstacle avoidance through different arm configurations reaching the same point, singularity avoidance by taking alternative paths, and optimization of additional criteria like minimizing energy consumption or keeping joints away from limits. Human arms have seven degrees of freedom per arm, giving us the redundancy that enables reaching around obstacles while maintaining grasp orientation. The additional complexity of redundant arms trades off against these flexibility benefits.

The pattern becomes clear. More degrees of freedom enable more flexibility and capability. Each additional DOF adds independent motion capability. However, each DOF also adds mechanical complexity, control difficulty, and cost. Robot arms feature precisely as many degrees of freedom as their applications require. Pick-and-place operations in a plane might use three DOF. Complex manipulation in three dimensions requires six DOF. Obstacle-rich environments or specialized requirements might justify seven or more DOF. Understanding this DOF-capability relationship helps you appreciate why robot arms have the number of joints they do rather than fewer or more.

Degrees of Freedom in Mobile Robots

Mobile robots demonstrate degrees of freedom through their motion capabilities on surfaces or through three-dimensional space. The locomotion mechanism determines available degrees of freedom for the mobile platform.

A simple differential-drive robot with two independently driven wheels has two degrees of freedom for controlling motion. One DOF controls overall speed by setting both wheels to the same velocity. The second DOF controls rotation rate by driving wheels at different speeds. These two control degrees of freedom fully specify how the robot moves at any instant. However, the robot’s actual position and orientation in space has three DOF: two for position (x, y coordinates) and one for heading angle. The robot cannot directly control all three simultaneously because it cannot move sideways. This difference between control DOF and configuration space DOF characterizes nonholonomic systems where instantaneous motion capabilities do not match configuration space dimensionality.

Four-wheeled cars demonstrate similar nonholonomic constraints. Cars have multiple wheels and steering mechanisms providing two control degrees of freedom: throttle/brake controlling forward speed, and steering controlling turning rate. The car’s configuration in space still has three DOF (x, y, heading), but the car cannot move instantaneously in all three directions. Cars cannot move sideways without first rotating to face the desired direction. This nonholonomic constraint explains why parallel parking takes multiple moves rather than simply sliding sideways into spaces.

Omnidirectional mobile robots using mecanum or omni-wheels achieve holonomic motion with three degrees of freedom. These specialized wheel designs enable sideways motion as well as forward and rotational motion. The three control DOF match the three configuration DOF for planar motion, allowing instantaneous motion in any direction without first rotating. Omnidirectional robots demonstrate improved maneuverability in confined spaces precisely because they possess sufficient degrees of freedom to move holonomically in the plane.

Drones and other flying robots operate in three-dimensional space with six degrees of freedom for position and orientation. Quadcopters accomplish six-DOF control through four rotors despite having more rotors than DOF. The additional rotor creates redundancy in the control system. Helicopters achieve six-DOF control through different actuators including main rotor collective pitch, cyclic pitch, tail rotor thrust, and overall throttle. However, helicopters’ instantaneous control freedom is less than six DOF—they cannot move directly sideways without tilting, creating some nonholonomic characteristics even in flight.

Legged robots present complex DOF analysis because each leg has multiple joints. A quadruped with three joints per leg has twelve degrees of freedom in its joint space. However, when all feet contact the ground, the body’s motion reduces to six DOF (three position, three orientation) due to constraints from ground contact. Understanding both the joint-space DOF and task-space DOF helps analyze legged robot capabilities. The many joint DOF enable choosing foot placement and achieving stable configurations, while the task-space DOF describes the body’s position and orientation relative to the ground.

Mobile robots illustrate that degrees of freedom analysis requires considering both control space (what you can directly control) and configuration space (all possible states). Nonholonomic constraints create interesting control challenges where configuration space DOF exceed control DOF, requiring motion planning algorithms that sequence controls over time to reach desired configurations.

Task Requirements and Necessary Degrees of Freedom

Different tasks require different minimum degrees of freedom to accomplish successfully. Understanding task requirements helps you design robots with appropriate DOF.

Positioning an object in a plane requires two degrees of freedom. Warehouse robots that move shelves within a flat warehouse need two DOF to position shelves at any floor location. The robots do not need to rotate shelves, elevate them, or tip them, so two DOF suffice for the task. The minimal DOF reduces mechanical complexity and control difficulty while fully satisfying functional requirements.

Orienting an object in a plane adds one degree of freedom. If the warehouse robot must also rotate shelves to specific angles for access, it needs three DOF: two for position, one for orientation. Many mobile robots operating on flat floors require exactly three DOF for this reason. The combination of planar position and heading angle fully specifies mobile robot configuration in typical operating environments.

Positioning and orienting objects in three-dimensional space requires six degrees of freedom. Assembly robots positioning components at any location with any orientation need six DOF. Surgical robots positioning instruments in three dimensions while maintaining specific tool orientations require six DOF. Inspection robots examining objects from arbitrary viewpoints need six DOF. Applications requiring full spatial control inevitably demand six-DOF robots.

Constrained-orientation tasks might require only position control. A robot placing objects on a shelf from above needs three DOF for positioning but might not need to orient the gripper if gravity naturally aligns downward-facing grasps. Recognizing when orientation requirements can be relaxed allows using simpler three-DOF systems instead of more complex six-DOF arms.

Cooperative manipulation with multiple robots can distribute DOF requirements. Two three-DOF arms working together can achieve six-DOF manipulation by coordinating their motions. Each arm contributes three DOF, and careful coordination produces the six DOF needed for complete pose control. While coordination adds control complexity, it potentially costs less than building a single six-DOF arm and provides redundancy through the multiple robots.

Path-constrained tasks may need fewer DOF than full spatial control. A painting robot following weld seams needs to position paint spray precisely along defined paths but does not need arbitrary three-dimensional positioning. The path constraint reduces effective DOF requirements. Similarly, inspection robots following pipes or structural elements operate in constrained environments where full six-DOF capability provides little benefit over simpler systems designed specifically for the constrained workspace.

Matching robot DOF to task requirements avoids both inadequate capability from too few DOF and unnecessary complexity from excess DOF. Every degree of freedom adds cost, mass, control complexity, and potential failure modes. Designs that carefully consider minimum necessary DOF produce simpler, more reliable, and more cost-effective robots than designs that reflexively pursue maximum DOF.

Workspace, Singularities, and DOF Limitations

Degrees of freedom determine fundamental capabilities, but they do not tell the complete story. Workspace shape, singularities, and practical limitations affect what DOF enable in practice.

Workspace describes the region where a robot can operate. A six-DOF arm can achieve any pose in six-dimensional space, but its physical workspace occupies a limited volume around its base. Typically, six-DOF arms access roughly hemispherical or roughly cylindrical volumes. Objects outside this workspace remain unreachable regardless of the arm’s six DOF. Degrees of freedom describe capability within the workspace but do not determine workspace size or shape, which depend on link lengths, joint ranges, and mechanical design.

Singularities are configurations where the robot loses degrees of freedom locally. At singular configurations, certain motions become impossible or require infinite joint velocities to achieve small end-effector motions. For example, a robot arm fully extended straight out reaches a singularity where end-effector motion radially outward is impossible—the arm cannot extend further because it is already maximally extended. Singularities reduce effective DOF locally even though the robot nominally has full DOF. Planning paths that avoid singularities becomes important for utilizing full robot capabilities.

Joint limits constrain the ranges through which joints can move. A rotational joint might rotate only 180 degrees rather than fully 360 degrees. These limits reduce workspace even though they do not change nominal DOF. A six-DOF arm with limited joint ranges cannot reach all poses in some workspace regions despite having six DOF in principle. Joint limits partition workspace into reachable and unreachable regions with complex boundaries.

Mechanical interference where parts of the robot collide with each other or with environment obstacles further restricts practical workspace. A six-DOF arm might theoretically reach a position, but the arm’s elbow collides with the base at the required joint configuration. Avoiding self-collision and environment collisions eliminates configurations from nominally-reachable workspace. The practical workspace accounting for collision avoidance typically considerably restricts the theoretical workspace based purely on kinematics.

Dexterity measures how easily the robot can move in different directions at a given configuration. Even with six DOF, some configurations provide better dexterity than others. Near singularities, dexterity drops precipitously as certain motions become difficult or impossible. Dexterity analysis helps choose configurations within the DOF that provide good motion capability in all relevant directions. High dexterity positions enable efficient task execution compared to low-dexterity configurations even though both have the same DOF.

Force and velocity capabilities vary with configuration even for robots with consistent DOF. A robot arm extended fully generates less force at the end-effector than when partially retracted because longer moment arms reduce effective torque. Configuration choices within available DOF significantly affect task performance beyond just kinematic reachability. Understanding these force-velocity-configuration relationships helps you operate robots effectively within their DOF constraints.

Degrees of freedom provide the upper bound on capability, but workspace analysis, singularity avoidance, joint limit respect, collision avoidance, and dexterity consideration all affect practical capability. Effective robot design and operation requires understanding both the fundamental DOF limitations and these practical factors that determine how well the DOF translate into useful work.

Redundancy: When More DOF Than Necessary

When a robot has more degrees of freedom than the minimum required for a task, redundancy creates both opportunities and challenges worth understanding.

Redundancy defined means having more degrees of freedom than strictly necessary. A seven-DOF arm positioning and orienting objects in three-dimensional space has one redundant DOF because six suffice for full pose control. This extra degree of freedom means multiple joint configurations can achieve the same end-effector pose. Rather than a unique solution to inverse kinematics, redundant robots have an infinite family of solutions forming a subspace of possible configurations.

Null-space motion exploits redundancy by moving joints without changing end-effector pose. The null space contains joint motions that do not affect the task. For a seven-DOF arm, the null space has one dimension—a continuous family of joint configurations maintaining the same end-effector position and orientation. Moving through null space enables optimizing secondary objectives while maintaining primary task requirements. This optimization opportunity makes redundancy valuable despite added control complexity.

Obstacle avoidance benefits from redundancy by enabling motion around obstacles while maintaining end-effector pose. If the direct path to a desired pose would cause collision, null-space motion can adjust the arm configuration to avoid obstacles without abandoning the pose goal. Redundant robots navigate cluttered environments more effectively than minimal-DOF robots because they have configuration flexibility beyond task requirements.

Singularity avoidance uses redundancy to escape or avoid singular configurations. Near singularities, redundant DOF provide alternative paths achieving desired motions without passing through the singularity. This capability enables smooth, continuous motion through workspace regions where minimal-DOF robots would encounter singularities requiring velocity discontinuities or impossible motions.

Joint limit avoidance through null-space motion keeps joints away from their range limits. A redundant arm approaching joint limits can use null-space motion to adjust configuration while maintaining end-effector position, preventing joints from reaching physical limits. This capability extends practical workspace and prevents control problems near joint limits.

Energy optimization through redundant DOF minimizes power consumption by choosing efficient configurations. Among the infinite configurations achieving a given pose, some require less motor torque due to favorable gravity loading or mechanical advantage. Null-space motion can transition between configurations to reduce energy consumption while maintaining pose.

The cost of redundancy includes increased mechanical complexity from additional joints, more complex control algorithms to resolve redundancy, and higher computational requirements for real-time redundancy resolution. Despite these costs, many modern manipulators incorporate redundancy specifically for the flexibility benefits it provides. Human arms having seven DOF per arm demonstrates that biological systems also evolved redundancy, presumably because flexibility advantages outweigh complexity costs.

Underactuated Systems: Fewer Actuators Than DOF

Some robots intentionally have fewer actuators than degrees of freedom, creating interesting capabilities through mechanical compliance and underactuation.

Underactuated defined means fewer actuators than DOF. A gripper with one motor opening and closing multiple fingers in a coordinated pattern exemplifies underactuation. The gripper might have several DOF describing all finger joint angles, but the single motor constrains these DOF to move together in a predetermined relationship. Underactuation trades independent control for mechanical simplicity and robust grasping.

Adaptive grasping through underactuation enables grippers to conform to object shapes automatically. As the underactuated fingers close around an irregular object, mechanical compliance lets different fingers stop at different angles when they contact the object. The result is an encompassing grasp that adapts to object geometry without requiring sensors or complex control determining each finger’s position independently. This passive adaptation through underactuation creates robust grasping with simple actuation and control.

Passive dynamic walking in legged robots uses underactuation where legs swing naturally under gravity and momentum rather than motors fully controlling each joint. These passive walkers achieve efficient locomotion by exploiting natural dynamics, using minimal actuation to maintain balance and provide energy rather than fighting dynamics with heavy actuation. The underactuation matches the mechanical system’s natural behavior, creating elegance and efficiency unachievable with full actuation.

Soft robots inherently exhibit extreme underactuation because continuous deformable materials have infinite configuration DOF but finite numbers of actuators. A soft pneumatic gripper might have three air chambers providing three actuation DOF, but the gripper’s rubber material can deform in infinite ways. The material’s compliance resolves the underactuation, deforming in response to contact forces to achieve stable grasps despite massive underactuation.

Human hands demonstrate natural underactuation in some motions. While hands can move fingers independently when concentrated, reflexive grasping synergies coordinate multiple joints through common neural patterns. These synergies functionally reduce control DOF, simplifying grasping by activating predefined coordination patterns rather than independently controlling every joint. This biological underactuation hints that independent control of all DOF is not always optimal even when possible.

Underactuated systems challenge traditional control approaches because you cannot directly command all configuration DOF independently. Instead, you control the available actuators and the system’s dynamics determine final configuration. This indirect control requires understanding system dynamics and exploiting mechanical properties intelligently. When designed well, underactuated systems achieve impressive capabilities with elegant simplicity. Poor underactuation design creates unreliable systems with behaviors difficult to predict or control.

Degrees of Freedom in Mobile Manipulation

Mobile manipulators combining mobile bases with robot arms demonstrate how DOF from different subsystems combine to create overall system capability.

Simple addition of DOF from base and arm gives total system DOF. A six-DOF arm mounted on a three-DOF mobile base creates a nine-DOF mobile manipulator. These nine DOF enable positioning the base anywhere in the plane with any heading, then using the arm’s six DOF to achieve any pose within the arm’s workspace relative to the base. The combined system has much larger effective workspace than either component alone.

Coordinated motion using both base and arm DOF simultaneously enables efficient operation. Rather than moving the base to position the arm workspace, then using only the arm for manipulation, coordinated whole-body motion moves base and arm together. This coordination can optimize energy consumption, reduce manipulation time, or enable manipulating objects while moving. However, coordination requires planning in the full nine-dimensional space, significantly increasing computational complexity.

Redundancy in mobile manipulators often provides more DOF than strictly necessary. Nine DOF exceeds the six needed for full pose control of the end-effector, creating three redundant DOF. This redundancy enables obstacle avoidance, base positioning that simplifies arm control, or maintaining preferred robot postures while accomplishing tasks. The redundancy provides flexibility in how the mobile manipulator approaches and executes tasks.

Base positioning as primary motion with arm positioning as fine adjustment represents a common strategy. The mobile base positions the robot roughly where needed using its three DOF, then the arm makes fine adjustments using its six DOF. This hierarchical decomposition simplifies planning by separating coarse base motion from precise arm manipulation. However, it does not exploit full redundancy or coordinated motion capabilities.

Task-relevant DOF analysis helps optimize control. For tasks that do not require base rotation, the mobile base effectively provides only two DOF, reducing the system to eight task-relevant DOF. Recognizing when full system DOF are not needed simplifies control while still accomplishing tasks. This selective DOF utilization balances capability against complexity.

Mobile manipulation represents the frontier of service robotics precisely because combined mobility and manipulation enable diverse tasks in unstructured environments. Understanding how base DOF and arm DOF combine, how redundancy affects planning, and how coordinated motion enables efficient operation helps you design and control mobile manipulators effectively. The mobile manipulation DOF analysis builds directly on understanding individual mobile robot DOF and manipulator arm DOF separately.

Practical Design Implications

Understanding degrees of freedom profoundly influences robot design decisions from earliest conception through detailed implementation.

DOF requirements follow from task analysis. Before designing a robot, carefully analyze what the robot must accomplish. Does it need to reach positions in three dimensions? Does orientation matter? Can some motions be constrained by the environment or task structure? This analysis determines minimum necessary DOF, preventing both inadequate designs with too few DOF and over-complex designs with unnecessary DOF.

Cost per degree of freedom grows with each additional DOF. Each joint requires motors, bearings, structural support, sensors, and control electronics. Adding DOF multiplies robot cost approximately linearly for simple designs and faster than linearly for complex designs where additional DOF require larger support structures and more sophisticated control. Minimizing DOF while meeting task requirements directly reduces cost.

Control complexity increases rapidly with DOF. A two-DOF arm has straightforward inverse kinematics you can solve analytically. A six-DOF arm requires numerical methods for inverse kinematics and sophisticated motion planning. Additional DOF make control challenges grow faster than DOF count because the configuration space dimensionality and planning complexity scale with DOF. Every DOF you can eliminate simplifies control substantially.

Reliability generally decreases as DOF increase because each joint represents a potential failure point. More complex mechanisms with more joints accumulate higher failure probabilities. Designs minimizing DOF while achieving required capability tend toward better reliability through mechanical simplicity. This reliability-DOF relationship argues for conservative DOF choices unless additional capability clearly justifies added risk.

Mechanical design choices affect achievable DOF. Serial manipulators with chains of joints naturally create DOF equal to joint count. Parallel mechanisms using multiple actuators working cooperatively can create limited DOF with higher stiffness and load capacity. Cable-driven mechanisms can achieve multiple DOF with remote actuation. Understanding how mechanism architecture creates DOF helps you choose appropriate designs for specific applications.

Redundancy considerations balance complexity against flexibility. Redundant DOF add cost and control complexity but provide operational benefits in obstacle-rich environments or when optimizing multiple objectives simultaneously. The decision whether to include redundant DOF depends on application requirements, operating environment structure, and acceptable complexity levels.

Practical robot design requires carefully thinking through DOF requirements, choosing mechanism architectures achieving necessary DOF efficiently, and implementing appropriate control approaches for the selected DOF. This DOF-driven design thinking produces robots well-matched to tasks without excessive complexity. Understanding degrees of freedom as a fundamental design parameter empowers you to make these design decisions thoughtfully.

Conclusion: DOF as Robot Capability Metric

Degrees of freedom provide powerful conceptual tool for understanding robot capabilities, limitations, and design tradeoffs. This single number captures fundamental information about what a robot can accomplish, though real capability depends on workspace, singularities, and implementation quality as well.

When you encounter robot specifications listing degrees of freedom, you now understand what that number reveals. Low DOF indicates simple mechanisms suited for constrained tasks. Six DOF suggests full spatial positioning and orientation capability. Higher DOF implies redundancy providing operational flexibility or multiple robot sections combining their capabilities. The DOF specification immediately tells you fundamental information about robot architecture and capability.

Analyzing tasks through DOF requirements helps you choose appropriate robots or design adequate systems. How many dimensions does the task span? Must the robot position objects, orient them, or both? Can environmental constraints reduce necessary DOF? These questions lead to minimum DOF requirements that guide robot selection or design. Matching robot DOF to task requirements produces effective solutions.

Understanding DOF limitations prevents unrealistic expectations. A three-DOF arm cannot orient objects arbitrarily no matter how clever the control algorithms. A two-DOF mobile base cannot move sideways without rotating. These DOF constraints are fundamental limitations that no amount of software sophistication can overcome. Recognizing fundamental limitations prevents pursuing impossible solutions.

Degrees of freedom concept extends beyond robotics into general mechanical systems, computer graphics, and physics simulations. The same DOF analysis applies to understanding vehicle suspension systems, computer-animated character rigs, or molecular structures. Learning DOF through robotics provides conceptual tools applicable across engineering and science.

Your robotics journey will repeatedly encounter degrees of freedom as you design systems, analyze capabilities, and solve control problems. DOF thinking becomes natural framework for conceptualizing robot motion and capability. What initially seemed like abstract mathematical formalism reveals itself as practical tool directly connected to what robots can physically accomplish. Every joint you add, every constraint you impose, changes the degrees of freedom and thereby changes fundamental robot capabilities. Understanding this connection between DOF and capability transforms you from passively accepting robot designs to actively reasoning about why robots have the DOF they do and how DOF choices affect what robots accomplish.