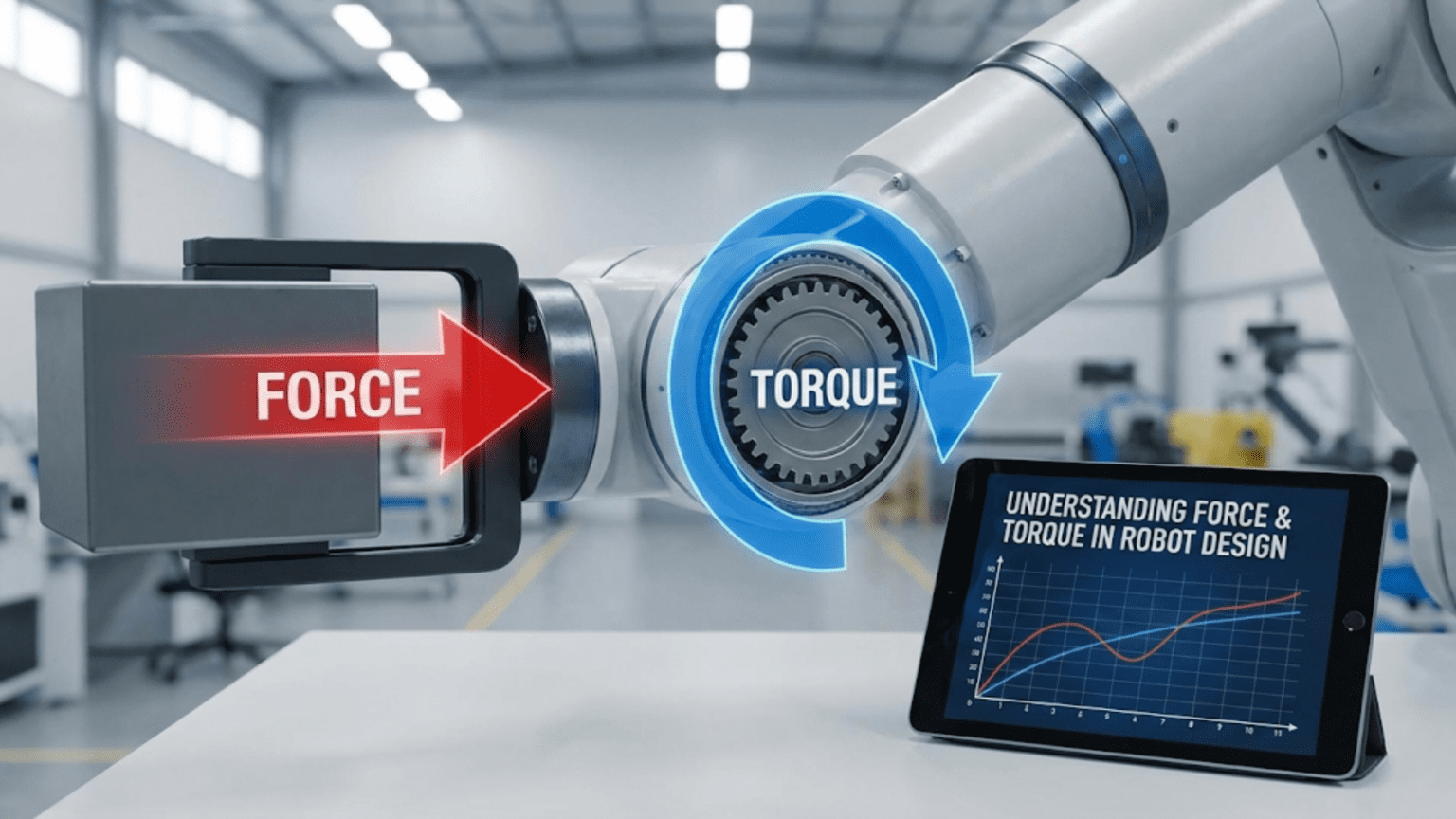

Force and torque are fundamental physical concepts that determine how robots interact with their environment and move effectively. Force is a push or pull measured in newtons, while torque is rotational force measured in newton-meters that causes objects to rotate around an axis. Understanding the relationship between force, torque, motor capabilities, and mechanical design is essential for building robots that can lift loads, climb obstacles, and perform intended tasks without stalling or burning out motors.

Introduction: Why Physics Matters in Practical Robotics

You’ve designed a robot arm to pick up objects, carefully assembled the mechanical structure, connected powerful-looking motors, and uploaded your code. You press the button to grab an object, and… the motor whines pathetically, the arm barely moves, or worse, the motor overheats and stops working entirely. What went wrong? The answer lies in understanding force and torque—concepts that might seem abstract and mathematical but are absolutely fundamental to building robots that actually work.

Many beginners approach robotics purely from an electronics and programming perspective, treating motors as magic boxes that make things move. Choose any motor, wire it up, write some code, and movement happens, right? This works fine for tiny, unloaded robots moving nothing but their own weight. But the moment you want your robot to lift something, push against resistance, climb a slope, or perform any real work, you enter the realm where physics becomes unavoidable.

Force and torque aren’t just theoretical concepts from physics textbooks—they’re practical tools that answer critical design questions. How much weight can my robot arm lift? Will my robot have enough power to climb this ramp? Why does my robot move slowly when I thought the motor was fast? Which motor should I choose for my application? What gear ratio do I need? These questions all require understanding force and torque relationships.

This comprehensive guide demystifies force and torque for roboticists who might feel intimidated by physics equations. We’ll build intuition through real-world examples before introducing any math. When we do use equations, they’ll be simple and directly applicable to robot design decisions. You’ll learn to calculate the forces and torques your robot needs to generate, understand motor specifications in datasheets, design mechanical systems that efficiently convert motor output into useful work, and troubleshoot why robots don’t perform as expected.

The beautiful thing about force and torque in robotics is that you don’t need advanced physics knowledge. A few fundamental principles and simple calculations empower you to design robots intelligently rather than through trial-and-error. Whether you’re building a wheeled rover that needs to overcome friction, a robotic arm that must lift payloads, or a walking robot that must support its own weight, the same force and torque concepts apply.

By the end of this guide, you’ll think about robot design differently. Instead of randomly selecting motors and hoping they work, you’ll confidently calculate requirements, choose appropriate components, and design mechanical systems optimized for your application. Let’s transform force and torque from intimidating physics concepts into practical design tools you use every day in robotics.

Force Fundamentals: Understanding Pushes and Pulls

Before tackling torque, let’s ensure we have a solid grasp of force itself. Force is wonderfully intuitive once you look past the physics terminology—it’s simply a push or pull on an object.

What Is Force in Practical Terms?

When you push a book across a table, you’re applying force. When gravity pulls an object downward, that’s force. When a motor drives a robot forward, the wheels push backward against the ground with force, and the ground pushes forward on the wheels with equal force (Newton’s third law), propelling the robot forward.

Force has two critical characteristics: magnitude (how strong the push or pull is) and direction (which way it pushes or pulls). A 10-newton force pushing left is different from a 10-newton force pushing right, even though the magnitude is the same. In robotics, we constantly work with forces in different directions: wheels pushing against the ground, arms lifting weights upward against gravity, grippers squeezing objects inward.

The standard unit of force is the newton (N), named after Isaac Newton. One newton is approximately the force required to hold a small apple (about 100 grams) against gravity. For perspective, lifting a 1-kilogram object requires roughly 10 newtons of force to overcome gravity. A strong adult human can exert hundreds of newtons of force, while industrial robots can exert thousands.

In the United States, you might encounter pounds-force (lbf) instead of newtons. The conversion is straightforward: 1 pound-force equals approximately 4.45 newtons. When a motor datasheet specifies torque in oz-in (ounce-inches), you’re working with imperial units that require conversion for use in standard physics equations.

The Relationship Between Force, Mass, and Acceleration

Newton’s second law connects force to motion through the equation F = ma, where F is force, m is mass, and a is acceleration. This deceptively simple equation is incredibly powerful for robot design.

The equation tells us that applying force to an object causes it to accelerate—to change its velocity. The more massive the object, the more force required to achieve the same acceleration. This explains why your robot needs more powerful motors when you add weight. The motors must generate sufficient force to accelerate the now-heavier robot at an acceptable rate.

When your robot is moving at constant velocity (not accelerating), the net force is zero. Forces still exist—friction, air resistance, and motor driving force—but they balance. Your robot’s motors must generate exactly enough force to overcome friction and resistance to maintain constant speed. To accelerate, motors must generate force exceeding friction and resistance.

For a wheeled robot on flat ground, calculate the force needed to accelerate it: F = ma. If your robot has mass of 2 kg and you want acceleration of 0.5 m/s², you need F = 2 kg × 0.5 m/s² = 1 newton of driving force. This seems small, but remember you also must overcome friction and any slope resistance simultaneously, which we’ll explore later.

Gravity: The Constant Force Acting on All Robots

Gravity is the ever-present force pulling all objects toward Earth’s center. For robot design, gravity matters enormously because it determines how much force is required to lift things, climb slopes, and even just stand upright.

The force of gravity on an object (its weight) equals mass times gravitational acceleration: F = mg, where g = 9.8 m/s² on Earth (often rounded to 10 m/s² for simplified calculations). A 1 kg object experiences 9.8 newtons of gravitational force. A 5 kg robot experiences 49 newtons pulling it downward.

This gravitational force is what your robot must overcome when lifting objects. To lift a 500-gram object, your robot must generate at least 5 newtons of upward force (slightly more to accelerate it upward, exactly 5 newtons to hold it stationary). When your robot arm fails to lift something, it’s because the motor’s force output is insufficient to overcome gravity acting on the object plus the arm’s own weight.

On slopes, gravity creates a component of force pulling the robot downhill. A robot on a 30-degree incline experiences half of its weight as a force pulling it back down the slope. Motors must generate enough force to overcome this gravitational component plus friction to climb successfully. This is why robots that move easily on flat ground struggle on even modest slopes.

Contact Forces: Friction and Normal Forces

When surfaces touch, contact forces arise. The normal force is the perpendicular push that surfaces exert on each other. When your robot sits on the ground, the ground pushes upward with a normal force exactly equal to the robot’s weight (assuming level ground), preventing it from sinking through the floor.

Friction is the parallel force that resists sliding between surfaces. Friction depends on the normal force and the coefficient of friction (a number representing how “sticky” the surfaces are): F_friction = μ × F_normal. Smooth surfaces like polished metal on plastic have low coefficients of friction (μ ≈ 0.1), while rough surfaces like rubber on concrete have high coefficients (μ ≈ 0.7 or higher).

For wheeled robots, friction is necessary for movement. When wheels try to rotate, friction between tire and ground prevents slipping, converting rotational motion into forward thrust. Insufficient friction (think of wheels spinning on ice) prevents effective movement. Too much friction increases the force motors must generate to maintain motion.

Friction opposes motion, so your robot’s motors must generate force exceeding friction to move. For a 2 kg robot on a surface with μ = 0.3, the normal force equals weight (20 N), so friction force equals 0.3 × 20 N = 6 N. Motors must generate more than 6 N to start movement and maintain at least 6 N to overcome friction once moving (in practice, static friction is slightly higher than kinetic friction).

Torque: Rotational Force That Makes Things Spin

While force causes linear motion, torque causes rotational motion. Most robot actuators—motors, servos, and gear systems—produce torque, making torque the currency of robot movement.

What Exactly Is Torque?

Torque is force applied at a distance from a rotation axis, creating a twisting or turning effect. Imagine using a wrench to loosen a bolt: you apply force to the wrench handle, and because that force acts at a distance from the bolt’s center, it creates torque that rotates the bolt.

Mathematically, torque equals force times the perpendicular distance from the rotation axis to where the force is applied: τ = F × r, where τ (Greek letter tau) represents torque, F is force, and r is the radius or lever arm distance. The standard unit for torque is the newton-meter (N⋅m), representing one newton of force applied one meter from the rotation axis.

The lever arm distance r is crucial. Applying the same force farther from the rotation axis generates more torque. This is why wrenches work—the long handle lets you apply force far from the bolt, multiplying your torque. In robotics, this same principle appears everywhere: longer robot arms generate more torque at the base joint for the same motor force, larger wheels generate more ground speed but less climbing torque, and gear ratios trade rotational speed for increased torque.

Torque has direction—clockwise or counterclockwise. In robot design, we often care about the magnitude (how much torque) and which direction it acts. A motor producing 5 N⋅m clockwise torque can be reversed to produce 5 N⋅m counterclockwise torque, enabling bidirectional control.

Converting Between Torque and Force

Understanding the relationship between torque and force is essential because motors produce torque, but robots often need to generate linear force (lifting weight, pushing objects, climbing slopes). The conversion depends on the radius at which the force acts.

For a simple wheel, the force at the ground equals the motor torque divided by the wheel radius: F = τ / r. A motor producing 1 N⋅m of torque driving a wheel with 0.1 m radius (10 cm) generates 10 newtons of force at the ground. The same motor driving a wheel with 0.05 m radius (5 cm) generates 20 newtons—smaller wheels give more force but less speed.

For a robot arm, the weight the arm can lift depends on torque and arm length. If a motor at the shoulder produces 2 N⋅m of torque and the arm extends 0.2 m, the maximum weight it can hold horizontally equals torque divided by length: F = 2 N⋅m / 0.2 m = 10 N, or about 1 kg. Extend the arm to 0.4 m, and the maximum weight drops to 5 N or 0.5 kg. This is why robot arms can lift heavier weights when retracted than when fully extended.

The beautiful symmetry is that torque equals force times radius, so force equals torque divided by radius. When you know a motor’s torque output and the radius at which you’re applying it, you can immediately calculate the force generated. This simple relationship guides countless robot design decisions.

Torque in Motor Specifications

Motor datasheets specify torque in several ways, and understanding these specifications is critical for selecting appropriate motors.

Stall torque is the maximum torque a motor can produce when prevented from rotating. This represents peak torque capability, but operating continuously at stall torque overheats and damages motors. Stall torque is useful for understanding absolute limits but isn’t a sustainable operating point.

Rated torque or continuous torque is the torque a motor can safely produce indefinitely without overheating. This is the specification to design around for sustained operations. A motor might have 10 N⋅m stall torque but only 3 N⋅m rated torque—you can briefly demand 10 N⋅m, but continuous operation should stay below 3 N⋅m.

Torque-speed curves show how motor torque varies with rotation speed. Motors produce maximum torque at zero speed (stall) and zero torque at maximum no-load speed. Between these extremes, torque decreases approximately linearly with increasing speed for DC motors. Understanding this curve helps you select operating points balancing speed and torque for your application.

Some motors specify torque at a particular voltage and current. Remember that torque approximately proportional to current for DC motors. Higher current means more torque but also more power consumption and heat generation. Voltage affects speed more than torque. Understanding these relationships lets you predict motor performance at different operating conditions.

Calculating Torque Requirements for Common Robot Applications

Theory becomes practical when you can calculate the actual torque requirements for your robot designs. Let’s work through common scenarios with real numbers.

Calculating Torque for Wheeled Robots

A wheeled robot needs sufficient torque to overcome rolling friction, accelerate, and climb slopes. Let’s calculate requirements for a concrete example.

Suppose you’re building a 3 kg robot with 10 cm diameter wheels (5 cm radius). On flat, smooth ground with coefficient of friction μ = 0.2, calculate the required motor torque to move at constant speed.

First, find friction force: F_friction = μ × m × g = 0.2 × 3 kg × 10 m/s² = 6 N. This is the force the wheels must generate at the ground to overcome friction. Convert force to torque using wheel radius: τ = F × r = 6 N × 0.05 m = 0.3 N⋅m per wheel.

If your robot has two drive wheels, each motor needs to produce at least 0.3 N⋅m. In practice, design for 50-100% safety margin, so select motors rated for 0.45 to 0.6 N⋅m continuous torque. This margin accounts for additional friction from real-world surfaces, battery voltage drop, and unexpected resistance.

Now add a slope. If this robot must climb a 20-degree incline, gravitational force pulling it backward equals m × g × sin(20°) = 3 kg × 10 m/s² × 0.342 = 10.26 N. Add this to friction force (still present) for total: 16.26 N. Convert to torque: τ = 16.26 N × 0.05 m = 0.81 N⋅m per wheel.

Suddenly your requirements jumped from 0.3 N⋅m to 0.81 N⋅m—nearly triple! This illustrates why robots that work fine on flat ground fail on slopes. With safety margin, you now need motors rated for approximately 1.2 N⋅m continuous torque to reliably climb 20-degree slopes.

Calculating Torque for Robot Arms

Robot arms lifting objects require even more careful torque calculation because the effective lever arm changes with arm position.

Consider a robot arm with a motor at the shoulder joint and a 30 cm arm length. You want to lift a 500-gram object at the end of the arm. Calculate the required shoulder torque.

The weight creates a downward force: F = m × g = 0.5 kg × 10 m/s² = 5 N. This force acts 30 cm from the shoulder joint, creating torque: τ = F × r = 5 N × 0.3 m = 1.5 N⋅m.

But wait—you forgot the arm’s own weight! If the arm itself weighs 200 grams, its weight (2 N) acts at its center of mass, approximately halfway along the length (15 cm from shoulder). This adds torque: τ_arm = 2 N × 0.15 m = 0.3 N⋅m.

Total torque requirement is 1.5 + 0.3 = 1.8 N⋅m just to hold the arm horizontally with the object. To raise it, you need additional torque to accelerate upward. A 50% safety margin suggests selecting a motor rated for approximately 2.7 N⋅m.

Here’s the critical insight: when the arm is vertical (pointing straight up), the weight acts directly through the shoulder axis with zero perpendicular distance, so torque required is nearly zero. When horizontal, torque is maximum. Robot arms must have motors sized for worst-case positions, typically when the arm extends horizontally with maximum load.

Calculating Torque for Grippers

Grippers need sufficient torque to squeeze objects with adequate force without crushing them.

If your gripper has fingers 5 cm long (from servo axis to contact point), and you need 10 N of gripping force to hold an object securely, calculate required servo torque.

Using τ = F × r: τ = 10 N × 0.05 m = 0.5 N⋅m. Look for servo motors rated at least 0.5 N⋅m (often specified as 50 kg⋅cm in servo datasheets, which equals approximately 5 N⋅m—more than sufficient).

Gripper design often uses leverage to amplify force. If you add linkages that create a mechanical advantage of 2:1, the servo needs only half the torque (0.25 N⋅m) to generate the same gripping force. However, mechanical advantage reduces the gripper’s opening range—trade-offs exist between force and travel distance.

Torque Requirements Table for Common Scenarios

| Application | Typical Torque Range | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Small wheeled robot (0.5-2 kg) on flat surface | 0.1 – 0.5 N⋅m per wheel | Robot weight, wheel radius, surface friction |

| Medium wheeled robot (2-5 kg) on flat surface | 0.5 – 2 N⋅m per wheel | Robot weight, wheel radius, surface friction |

| Wheeled robot climbing 15-20° slopes | 2-3x flat-surface torque | Slope angle, total weight |

| Small robot arm (20-40 cm) lifting 100-500g | 1 – 3 N⋅m at shoulder | Arm length, object weight, arm weight |

| Medium robot arm (40-80 cm) lifting 500g-2kg | 3 – 10 N⋅m at shoulder | Arm length, object weight, arm weight |

| Gripper for small objects (< 500g) | 0.2 – 1 N⋅m | Finger length, required grip force, object fragility |

| Gripper for larger objects (500g – 2kg) | 1 – 5 N⋅m | Finger length, required grip force, object fragility |

| Legged robot joint (small, < 1 kg robot) | 0.5 – 2 N⋅m per leg joint | Leg length, robot weight, gait dynamics |

| Rotating sensor platform | 0.05 – 0.2 N⋅m | Platform weight, rotation speed requirements |

The Power-Speed-Torque Relationship

Motors don’t just produce torque—they also rotate at certain speeds and consume electrical power. Understanding how these three quantities relate is crucial for complete motor selection and robot design.

The Fundamental Trade-off: Speed Versus Torque

For a given motor at a specific voltage, increasing torque decreases speed, and vice versa. This isn’t arbitrary—it’s fundamental to how motors work. The torque-speed curve mentioned earlier shows this inverse relationship graphically.

At no load (zero torque demand), motors spin at maximum speed. As you increase torque demand by adding load, the motor slows down. At stall (maximum torque), speed is zero. This trade-off means you can’t simultaneously have maximum speed and maximum torque from the same motor.

For robotics, this creates design decisions. Do you want a fast robot that can’t overcome much resistance, or a slow, powerful robot that climbs obstacles easily? Often, you want both—which is where gears become essential, a topic we’ll explore shortly.

The specific torque-speed relationship depends on motor type. Brushed DC motors have approximately linear torque-speed curves. Brushless motors can have different curve shapes. Servo motors include internal gearing that modifies the torque-speed relationship. Always consult motor datasheets for actual performance curves rather than assuming ideal linear relationships.

Understanding Mechanical Power

Mechanical power is the rate at which work is done, measured in watts (W). For rotational systems, power equals torque times angular velocity: P = τ × ω, where ω (omega) is angular velocity in radians per second.

If you’re more comfortable with RPM (revolutions per minute), convert to radians per second: ω = (RPM × 2π) / 60. For example, 100 RPM equals approximately 10.47 rad/s.

A motor producing 1 N⋅m of torque while rotating at 100 RPM (10.47 rad/s) generates mechanical power: P = 1 N⋅m × 10.47 rad/s = 10.47 watts. The same motor at 200 RPM (with reduced torque due to the torque-speed curve) might produce 0.6 N⋅m torque and generate P = 0.6 × 20.94 = 12.6 watts.

Interestingly, motors often deliver maximum mechanical power output at approximately 50% of their no-load speed. Operating near this point maximizes efficiency for converting electrical power into mechanical work. Designing your robot to operate motors in this sweet spot improves battery life and performance.

Electrical Power and Efficiency

Motors consume electrical power: P_electrical = V × I, where V is voltage and I is current. Not all electrical power becomes mechanical power—some is lost as heat due to resistance in windings, friction in bearings, and other inefficiencies.

Motor efficiency equals mechanical power output divided by electrical power input: η = P_mechanical / P_electrical. Good DC motors achieve 70-85% efficiency at their optimal operating point. Cheaper motors might be only 40-60% efficient, meaning more than half the battery power becomes heat rather than useful motion.

Understanding efficiency helps calculate battery life. If your robot requires 20 watts of mechanical power and your motors are 75% efficient, they consume 20 W / 0.75 = 26.7 watts electrical power. With a 7.4V battery, this means current draw of 26.7 W / 7.4 V = 3.6 amperes. A 2000 mAh battery would last approximately 2000 mAh / 3600 mA = 0.56 hours or about 33 minutes of continuous operation.

Always consider efficiency in power calculations. Assuming 100% efficiency leads to overly optimistic battery life estimates and undersized power supplies. Real-world robots need safety margins accounting for inefficiency and battery voltage drop under load.

Gears: Trading Speed for Torque

Gears are fundamental mechanical components that let you optimize the speed-torque trade-off for your specific application. Understanding how gears modify torque and speed is essential for effective robot design.

How Gears Modify Torque and Speed

Gears transfer rotational motion between shafts while changing the speed and torque. The gear ratio determines the modification. If a small gear with 10 teeth drives a large gear with 30 teeth, the gear ratio is 30:10 or 3:1 (often written as just “3:1” or “1:3” depending on convention).

In a 3:1 reduction (the more common notation), the output shaft rotates 3 times slower than the input but produces 3 times the torque. If the motor produces 0.5 N⋅m at 300 RPM, after the 3:1 reduction, you get 1.5 N⋅m at 100 RPM. You’ve traded speed for torque.

The trade-off is exact (ignoring friction losses): torque multiplication equals speed reduction. A 10:1 reduction gives 10 times the torque but 1/10th the speed. A 1:2 ratio (speed increaser) gives twice the speed but half the torque. Gears cannot create energy—power in approximately equals power out (minus losses), so τ_in × ω_in ≈ τ_out × ω_out.

This principle lets you match motors to applications. Small, fast motors with low torque can drive high-torque applications through gearboxes. This is why most servo motors contain internal gear reductions—the actual motor might spin at 10,000 RPM with minimal torque, but the gearbox converts this to perhaps 60 RPM with substantial torque.

Selecting Gear Ratios for Robot Applications

How do you choose the right gear ratio? Start by calculating your torque requirement (using methods from earlier sections) and your motor’s available torque. The gear ratio needed equals required torque divided by motor torque.

Example: Your robot arm needs 2 N⋅m at the shoulder joint. You have a motor that produces 0.4 N⋅m. Required gear ratio: 2 / 0.4 = 5:1. Select a gearbox (or gear combination) providing approximately 5:1 reduction.

But wait—check the speed. If the motor spins at 6000 RPM and you want the arm to move at reasonable speed, calculate output speed: 6000 RPM / 5 = 1200 RPM. This is extremely fast for a robot arm—you’d want much higher reduction. Perhaps 50:1 or even 100:1 would be more appropriate, giving you 0.4 × 50 = 20 N⋅m torque at 120 RPM or 0.4 × 100 = 40 N⋅m at 60 RPM.

This illustrates an important point: you often select gear ratios based on both torque AND speed requirements. Calculate minimum ratio from torque, then verify the resulting speed is appropriate. If speed is too high, increase the ratio. If speed becomes too slow for your application, you might need a different motor with higher base torque.

Compound Gearing and Gear Trains

Sometimes you need gear ratios that aren’t available in single gear pairs. Compound gearing uses multiple stages to achieve higher ratios.

If you connect two gear pairs in series—first pair is 3:1 and second pair is 4:1—the overall ratio is 3 × 4 = 12:1. Each stage multiplies the previous stage’s reduction. This is how gearboxes achieve ratios like 100:1 or 200:1: multiple stages of more modest ratios (perhaps 5:1, 4:1, and 5:1 for a 100:1 total).

Each gear stage introduces some inefficiency due to friction. A single gear pair might be 95% efficient, but four stages in series give 0.95^4 = 81% efficiency. High-ratio gearboxes thus have lower efficiency than low-ratio ones. This is acceptable for most robotics applications but worth considering when optimizing for battery life.

Planetary gears provide compact, high-ratio reduction in small packages. Many servo motors and gear motors use planetary gearboxes internally. Worm gears provide very high ratios (20:1 or more) in single stages but have low efficiency (often 40-60%) and self-locking properties that prevent back-driving—useful for applications where you don’t want external forces to move the mechanism when unpowered.

Practical Motor Selection Based on Force and Torque Needs

Armed with force and torque knowledge, you can now select motors intelligently rather than guessing.

Step-by-Step Motor Selection Process

Step 1: Define your application requirements. What does the robot need to do? Lift how much weight over what distance? Move how much mass at what speed? Climb what slopes? Be specific: “Lift 500 grams with a 25 cm arm” or “Move a 2 kg robot at 0.5 m/s up 15-degree slopes.”

Step 2: Calculate force requirements. Using techniques from earlier sections, determine the forces involved. For lifting: F = m × g. For moving on slopes: F = m × g × sin(angle) + friction. For acceleration: F = m × a. Sum all forces to find total required force.

Step 3: Convert force to torque. Multiply force by the radius at which it acts. For wheels: τ = F × r_wheel. For arms: τ = F × arm_length. This gives you the minimum torque requirement at the motor output shaft (after any gearing).

Step 4: Account for gearing. If you plan to use gears, divide required torque by the gear ratio to find motor torque needed. For a 5:1 reduction gearbox, a 10 N⋅m requirement becomes 2 N⋅m motor requirement. Or, search for motors/servos with integrated gearing that directly provides your required output torque.

Step 5: Add safety margin. Never design right at the limit. Add 50-100% safety margin. If calculations show 1 N⋅m required, select motors rated for 1.5-2 N⋅m. This accounts for friction, inefficiencies, voltage drop, and unexpected loads.

Step 6: Verify speed is acceptable. Check that the motor’s speed (after gearing) suits your application. If your robot arm would swing wildly fast or painfully slow, revisit motor selection or gear ratio. Speed = motor_RPM / gear_ratio.

Step 7: Check electrical requirements. Verify the motor’s voltage and current requirements match your power supply capabilities. Calculate current draw at your operating torque and ensure your battery and motor driver can supply it.

Reading Motor Datasheets for Force and Torque Information

Motor datasheets contain the specifications you need, but you must know where to look and how to interpret the information.

Stall torque appears in most datasheets, often as the first torque specification listed. Remember this is maximum momentary torque, not continuous operating torque. Look for “rated torque” or “continuous torque” specifications for sustained operation limits.

Torque constant (K_t) relates current to torque: τ = K_t × I. If a motor has K_t = 0.05 N⋅m/A and draws 2 amperes, it produces 0.1 N⋅m torque. This helps you calculate torque at different current levels and estimate current draw for desired torque.

Speed constant (K_v) or no-load speed tells you how fast the motor spins unloaded. Measured in RPM/volt (or rad/s/volt), this helps predict speed at different voltages. A motor with 1000 RPM/V running at 12V spins approximately 12,000 RPM unloaded.

Torque-speed curves graph the relationship between torque and speed. Find your required torque on the vertical axis, trace horizontally to the curve, then drop vertically to read the corresponding speed. This shows whether the motor can deliver your required torque at acceptable speed.

Gear ratio specifications appear on geared motors and servos. A servo rated at “10 kg⋅cm” torque with internal gearing might use a 100:1 reduction. Understanding the gearing helps you comprehend performance characteristics and whether the internal gearing suits your application.

Common Force and Torque Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even with solid understanding, certain errors plague robot designers. Recognizing these patterns helps avoid them.

Mistake 1: Forgetting Component Weight

Beginners calculate payload capacity but forget the weight of robot components themselves. A robot arm designed to lift 500 grams sounds impressive until you realize the arm weighs 400 grams—the motor must actually handle 900 grams total.

Always include component weight in calculations. Weigh your structural materials, motors, batteries, and electronics. Sum everything that the motor must move or lift. The motor cares about total mass, not just payload mass.

For multi-link robot arms, each joint must support the weight of all components beyond it. The shoulder joint carries the entire arm, elbow joint, and payload. The elbow joint carries only the forearm and payload. Calculate cumulative weight for each joint from the end effector backward to the base.

Mistake 2: Ignoring Leverage Effects

Distance from the rotation axis dramatically affects torque requirements, but beginners sometimes overlook this when components aren’t exactly at the end of arms or levers.

A 100-gram sensor mounted 40 cm from a robot arm shoulder creates 100 g × 0.4 m × 10 m/s² = 0.4 N⋅m of torque load. Move that sensor to 20 cm from the shoulder, and torque drops to 0.2 N⋅m—half as much despite identical weight. Mounting heavy components closer to joints reduces torque requirements significantly.

For wheeled robots, wheel diameter is the leverage arm. Larger wheels need more torque to generate the same ground force. If you switch from 10 cm diameter wheels to 15 cm diameter wheels, you need 50% more motor torque to maintain the same performance (or accept reduced performance).

Mistake 3: Using Peak Ratings Instead of Continuous Ratings

Datasheets list impressive peak or stall specifications that tempt designers. “This motor produces 5 N⋅m!” But reading carefully reveals that’s peak torque for a few seconds maximum, while continuous rating is only 1.5 N⋅m.

Operating motors at peak ratings continuously causes overheating and premature failure. Motors produce heat proportional to current squared, so high torque (high current) operation generates substantial heat. Continuous operation must stay within thermal limits.

Design for continuous ratings, using peak ratings only for brief acceleration or intermittent high-load situations. If your robot must sustain 2 N⋅m torque continuously, select a motor with at least 2 N⋅m continuous rating, even if a cheaper motor with 2 N⋅m peak but 1 N⋅m continuous rating seems tempting.

Mistake 4: Neglecting Efficiency and Real-World Losses

Calculations assuming 100% efficiency and zero friction invariably overestimate real performance. Motors aren’t 100% efficient, gears lose energy to friction, and bearings create resistance.

Apply realistic efficiency factors to calculations. Assume 70-80% motor efficiency for decent DC motors, 90-95% efficiency per gear stage, and account for bearing friction. If calculations show you need exactly 1 N⋅m at the output and you have a 5:1 gearbox with 90% efficiency, you need the motor to produce (1 N⋅m / 5) / 0.90 = 0.22 N⋅m rather than 0.20 N⋅m.

Safety margins partially compensate for efficiency losses, but explicitly accounting for efficiency produces more accurate predictions. Your 50% safety margin on top of efficiency-adjusted calculations provides true safety rather than just compensating for optimistic assumptions.

Mistake 5: Selecting Motors Based on Voltage and Current Alone

Some beginners choose motors by voltage compatibility: “I have a 12V battery, so I’ll use 12V motors.” While voltage must be compatible, torque and speed specifications matter far more for determining if a motor suits your application.

A tiny 12V motor producing 0.05 N⋅m and a large 12V motor producing 5 N⋅m both run on 12V, but they’re not interchangeable. One might be perfect for rotating a sensor platform while utterly inadequate for driving robot wheels.

Always start motor selection with torque and speed requirements. Voltage is a secondary consideration—you can use voltage regulators or different batteries to match motor voltage requirements, but you can’t make a low-torque motor magically produce high torque.

Advanced Concepts: Dynamic Forces and Acceleration

The calculations we’ve covered so far assume steady-state operation—constant speed movement, static loads, etc. Real robots accelerate, decelerate, and experience dynamic forces that require additional consideration.

Accounting for Acceleration in Force Calculations

When your robot accelerates, motors must generate extra force beyond what’s needed for constant-speed operation. This additional force creates the acceleration: F_acceleration = m × a.

For a 3 kg robot accelerating at 1 m/s², the acceleration force is 3 N. This adds to the force needed to overcome friction. If friction requires 5 N, total force during acceleration is 8 N. After reaching desired speed, you can reduce force back to 5 N to maintain constant velocity.

Rapid acceleration requires high forces (and thus high motor torques) even if cruise speed operation is less demanding. This is why cars need powerful engines for quick acceleration but can maintain highway speed with much less power. For robots, if you need rapid response and quick movements, size motors for acceleration requirements, not just steady-state needs.

The same principle applies to robot arms. Lifting a weight slowly requires torque = force × distance. Lifting it quickly requires additional torque to accelerate the mass upward. If you want fast, dynamic arm movements, increase motor torque beyond static calculations to account for acceleration torque.

Rotational Inertia and Angular Acceleration

Just as linear inertia (mass) resists linear acceleration, rotational inertia (moment of inertia) resists angular acceleration. Heavy objects far from the rotation axis have high rotational inertia, making them hard to spin up or slow down.

For rotation, torque creates angular acceleration: τ = I × α, where I is moment of inertia and α (alpha) is angular acceleration in radians/s². This is the rotational equivalent of F = m × a.

Calculating moment of inertia for complex shapes is mathematically involved, but you can approximate for simple cases. A wheel with mass m and radius r has I ≈ (1/2) × m × r². A thin rod rotating about one end has I ≈ (1/3) × m × L², where L is length.

The practical implication: when starting or stopping rotation of heavy wheels, long arms, or large mechanisms, motors need extra torque beyond what’s required for constant-speed rotation. This extra torque accelerates (or decelerates) the rotational inertia. For high-inertia systems, this can be significant—possibly doubling or tripling the torque needed compared to steady rotation.

Impact Forces and Collisions

When robots collide with objects or suddenly stop, impact forces can be enormous—far exceeding normal operating forces. A robot moving at 1 m/s that stops in 0.1 seconds experiences average deceleration of 10 m/s², creating forces of F = m × a. A 5 kg robot generates 50 N impact force—compare this to the perhaps 10 N needed for normal movement.

Impact forces stress mechanical structures, potentially damaging components or causing motors to stall. Good robot design includes compliance (some “give” in the structure), sensors to detect impending collisions, and software to decelerate before contact rather than crashing at full speed.

For motor protection, current limiting in motor drivers prevents damage from sudden stalls caused by collisions. When a collision stops a motor abruptly, current spikes (remember, stall current is very high). Current limiting circuits restrict current to safe levels, protecting both motor and driver circuitry.

Optimizing Designs for Mechanical Advantage

Beyond selecting appropriate motors, clever mechanical design amplifies force and torque to achieve better performance with given motors.

Leverage Principles in Robot Design

Levers multiply force at the cost of distance traveled. A lever with mechanical advantage of 3:1 triples the output force but requires three times the input movement distance.

In robot grippers, linkage designs create mechanical advantage. A servo rotating 90 degrees might close gripper fingers only 3 cm, but the linkage configuration multiplies force by 5:1. The servo produces 0.5 N⋅m torque, but gripper tips exert 5 times the force you’d get from direct servo attachment.

Robot arms sometimes use parallelogram linkages to maintain end-effector orientation while distributing weight across multiple joints. This improves load handling without requiring proportionally larger motors—clever design multiplies effectiveness.

The trade-off is always present: mechanical advantage for force means reduced speed and range of motion. Design levers and linkages to match your application’s priority—more force for heavy lifting, more speed and range for quick manipulation.

Reducing Unnecessary Weight

Every gram you remove from moving robot parts reduces force and torque requirements. Weight reduction is often more effective than selecting larger motors.

Use lightweight materials where strength permits. Aluminum instead of steel, carbon fiber instead of aluminum, or well-designed plastic instead of metal can dramatically reduce weight. A robot arm that weighs 200 grams requires half the motor torque of a functionally identical 400-gram arm.

Minimize material where stress is low. Hollow tubes provide nearly the strength of solid rods at fraction of the weight. Structures can use ribbed or honeycomb patterns, removing material where it doesn’t contribute to strength. 3D printing enables complex lightweight structures impossible with traditional manufacturing.

Place heavy components strategically. Batteries and motors close to joints reduce torque loading. A 500-gram battery mounted at the base of a robot arm contributes minimal shoulder torque, but the same battery at the arm’s end might create 5 N⋅m of torque load on the shoulder joint.

Optimizing Wheel and Gear Selection

For wheeled robots, wheel diameter affects the speed-torque trade-off. Larger wheels give higher top speed but reduce climbing ability. Smaller wheels provide better torque multiplication at the cost of maximum speed.

If you need both climbing ability and reasonable speed, consider adjustable gearing or multi-speed transmissions. Some advanced robots switch gear ratios depending on terrain—low gearing for climbing, high gearing for flat, fast travel.

Tire selection affects friction and efficiency. Hard plastic wheels roll efficiently on smooth surfaces but slip on rough terrain. Rubber tires provide traction for climbing but increase rolling resistance, requiring more torque for movement. Match tire characteristics to operating environment.

Force and Torque in Specific Robot Types

Different robot categories emphasize different aspects of force and torque. Understanding these patterns helps design category-appropriate robots.

Wheeled Mobile Robots

Wheeled robots prioritize forward driving force to overcome friction and climb slopes. Motor selection focuses on providing sufficient torque at wheels to generate required ground force.

Two-wheel differential drive robots split torque requirements between two motors. Each motor needs approximately half the total torque (accounting for weight distribution—if weight is uneven, motors need unequal torque capability). Four-wheel drive distributes torque across four motors, reducing per-motor requirements.

Battery weight significantly impacts wheeled robot performance. A robot designed to carry 5 kg payload struggles if you add a 3 kg battery without resizing motors. Plan for battery weight from the start, or use lighter lithium polymer batteries instead of heavier lead-acid batteries.

Robotic Arms and Manipulators

Arms amplify weight through leverage, making torque management critical. Each joint must handle cumulative weight of all components beyond it plus any payload.

Multi-joint arms have cascading requirements: the base must be strongest (supporting everything), each successive joint can be smaller (supporting less weight). This creates a natural tapering where base motors are largest and end-effector motors smallest.

Counterweights can reduce motor torque requirements. A weight opposite the arm balances the arm’s weight around the joint, reducing net torque. However, counterweights add total system weight and create their own complications when the arm moves.

Legged Robots

Legged robots face unique force and torque challenges. Leg joints must generate sufficient torque to lift and accelerate the entire robot’s weight with each step, often on just one or two legs while others are in swing phase.

Gait affects force requirements dramatically. Slow static gaits (where the robot’s center of mass always stays within the support polygon of grounded feet) require less dynamic force than fast dynamic gaits. Walking robots need less force per leg than running or jumping robots.

Leg length creates leverage similar to arms. Longer legs amplify weight, requiring more torque at hip joints. Short, stocky legs reduce torque requirements but limit stride length and maximum speed. Biological inspiration shows successful compromises—observe how animals with different body plans distribute leg length and muscle placement.

Measuring and Testing Force and Torque in Your Robots

Theory and calculations guide design, but real-world testing validates whether your robot performs as expected and helps diagnose problems.

Simple Force Measurement Techniques

A spring scale (like a fishing scale) measures force directly. Attach it between your robot and a fixed point, then operate the robot to measure pulling or pushing force. This works excellently for wheeled robots—measure the force generated at wheels against the ground by having the robot push against the scale.

For lift force, hang the object your robot should lift from a scale, then activate the robot arm or gripper and observe how much force it exerts. If the scale reading decreases by 500 grams (5 N), your robot is generating 5 N upward force.

Load cells provide more precise electronic force measurement. These sensors output voltage proportional to applied force, allowing you to log force data during operation and create force-time graphs showing how force varies throughout motion cycles.

Measuring Torque

Direct torque measurement requires torque sensors (expensive) or improvised torque arms. The torque arm method: attach a bar perpendicular to the motor shaft at known radius, apply measured force at the bar’s end, and calculate torque = force × radius.

For example, attach a 30 cm arm to a motor shaft. Hang a 1 kg weight (10 N force) at the arm’s end. If the motor holds it stationary, it’s producing 10 N × 0.3 m = 3 N⋅m torque. Add weight until the motor can barely hold—this approximates maximum continuous torque.

Indirect torque measurement uses current sensing. Measure motor current under various loads. Using the motor’s torque constant (from datasheet), calculate torque = K_t × current. A motor with K_t = 0.02 N⋅m/A drawing 5 amperes produces approximately 0.1 N⋅m torque.

Load Testing and Performance Validation

After building your robot, validate it meets performance requirements through load testing. For arms, try lifting the maximum rated payload at full extension. For wheeled robots, test climbing the steepest slope specified in requirements.

Monitor motor temperature during sustained operation. If motors overheat during normal use, they’re undersized or overloaded. Add cooling, reduce load, or select higher-torque motors. Temperature rise indicates how close you’re operating to thermal limits.

Measure actual battery life under realistic operating conditions. Calculate power consumption and compare to theoretical predictions. Significant discrepancies suggest inefficiencies in mechanical design, motor selection, or control algorithms that deserve investigation.

Troubleshooting Force and Torque Problems

When robots don’t perform as expected, force and torque analysis helps diagnose root causes.

Robot Can’t Lift or Move Expected Loads

If your robot struggles with loads that calculations suggested should work, several culprits are likely:

Motors undersized: Verify actual motor torque ratings match what you designed for. Stall torque isn’t continuous rating. Check that motor specifications match the datasheet and that you didn’t confuse similar-looking motors with different capabilities.

Excessive friction: More friction than anticipated increases force requirements. Check for binding in joints, poorly aligned components, or inadequate lubrication. Friction can double or triple force requirements compared to ideal calculations.

Voltage drop under load: Measure motor voltage while operating under load. Thin wires, weak batteries, or inadequate power supplies cause voltage drop, reducing available torque. Motors produce less torque at lower voltages.

Incorrect gear ratio: Verify gearing matches design specifications. Wrong gear combinations create unexpected ratios. A 4:1 reduction instead of 5:1 reduces output torque by 20%, potentially enough to cause failure.

Robot Moves Too Slowly

Slow movement despite powerful motors suggests gear ratio is too high, creating excessive torque multiplication at the expense of speed.

Check actual gear ratios against design specifications. Calculate the expected output speed: motor_RPM / gear_ratio. If this is much slower than desired, reduce gear ratio (accept less torque for more speed) or select a faster base motor.

Friction also slows robots. Excessive mechanical resistance forces motors to slow down to generate sufficient torque to overcome binding. Systematically check each moving joint for smooth operation.

Motors Overheat or Trigger Thermal Protection

Overheating indicates motors work too hard—either the load is too high or motors run too close to limits.

Reduce load if possible—lighten the robot, improve mechanical efficiency, reduce friction. If load can’t be reduced, select motors with higher continuous torque ratings. Remember: continuous operation requires continuous torque ratings, not peak ratings.

Improve cooling through heatsinks, fans, or better ventilation. Some applications benefit from duty cycle management—operate motors intermittently with rest periods allowing cooling between high-load operations.

Erratic or Jerky Movement

Erratic movement sometimes results from motors operating outside their optimal torque-speed range. When load exceeds motor capability, motors can’t maintain smooth rotation, producing stuttering motion.

Verify motors operate in the middle of their torque-speed curve, not at the extremes. Adjust gear ratios to shift operating point to more favorable regions of motor performance curves.

Control system issues also cause jerky motion. PID controller tuning problems, insufficient power supply filtering, or poor command signal quality create erratic behavior even with adequate motor torque. Distinguish mechanical (torque-related) issues from control issues through systematic testing.

Conclusion: Making Force and Torque Your Allies

Force and torque transform from abstract physics concepts into practical design tools when you understand how to apply them to real robot problems. The equations aren’t complicated—mostly multiplication and division with straightforward measurements. The key is developing intuition about how force, torque, distance, mass, and motion interrelate.

Start every robot design by calculating force and torque requirements before selecting components. This front-loaded engineering effort prevents expensive mistakes like purchasing inadequate motors or building robots that can’t perform their intended tasks. Fifteen minutes with a calculator saves hours of frustration and potentially hundreds of dollars in wrong component purchases.

Build safety margins into every design. Real-world friction, inefficiencies, and unexpected loads always exceed idealized calculations. Designing right at calculated limits invites failure. Add 50-100% margins for reliability and longevity.

Don’t fear the math. The force and torque calculations presented here use only basic arithmetic—multiplication, division, and occasional trigonometry for angles. If you can balance your checkbook, you can calculate robot force requirements. The physics makes sense when connected to concrete robot applications rather than abstract textbook problems.

Test and validate. Calculations guide design, but real-world testing reveals actual performance. Measure force output, monitor motor temperatures, and verify robots achieve intended capabilities. Discrepancies between predictions and reality teach you about factors you overlooked—valuable lessons for future designs.

Optimize through iteration. First designs rarely achieve optimal performance. Build, test, identify weaknesses, and refine. Perhaps motors need upgrading, gear ratios adjusting, or weight reducing. Each iteration informed by force and torque analysis produces better robots.

Remember that force and torque work together with all other aspects of robotics—electronics must supply adequate current for required torque, programming must control motors smoothly, and mechanical design must efficiently transmit forces. Understanding force and torque doesn’t replace understanding electronics or programming; it complements them, creating complete robot design capability.

The robot that effortlessly lifts its intended payload, climbs slopes smoothly, and operates reliably didn’t achieve this through luck—it resulted from proper force and torque engineering. You now possess the knowledge to design such robots. The motors you select will be appropriately sized. The gears you choose will provide optimal speed-torque trade-offs. The structures you build will efficiently handle forces without excess weight.

Force and torque mastery separates hobbyists randomly assembling components from engineers deliberately designing functional robots. Apply these principles to your next project, and you’ll see the difference immediately. Your robots will work better, perform more reliably, and achieve capabilities that previously seemed out of reach. That’s the power of understanding force and torque in robot design.

Key Takeaways

- Force is a push or pull measured in newtons; torque is rotational force measured in newton-meters that causes rotation around an axis

- Calculate force requirements by considering weight (F = m × g), acceleration (F = m × a), friction (F = μ × normal force), and slope climbing (F = m × g × sin(angle))

- Convert force to torque using the relationship τ = F × r, where r is the distance from the rotation axis to where force is applied

- Motors trade speed for torque: higher loads reduce speed, while lighter loads allow faster rotation according to the torque-speed curve

- Gear ratios multiply torque by the same factor they divide speed: a 5:1 reduction gives 5× torque but 1/5 speed

- Always design with 50-100% safety margins above calculated requirements to account for friction, inefficiencies, and unexpected loads

- Account for the weight of all robot components, not just payload—motors must move themselves and structural elements too

- Leverage effects are critical: force or weight acting farther from a joint requires proportionally more torque

- Use continuous torque ratings for sustained operation, not peak or stall torque specifications that motors can handle only briefly

- Test real robots under load to validate calculations and identify discrepancies between theory and practice