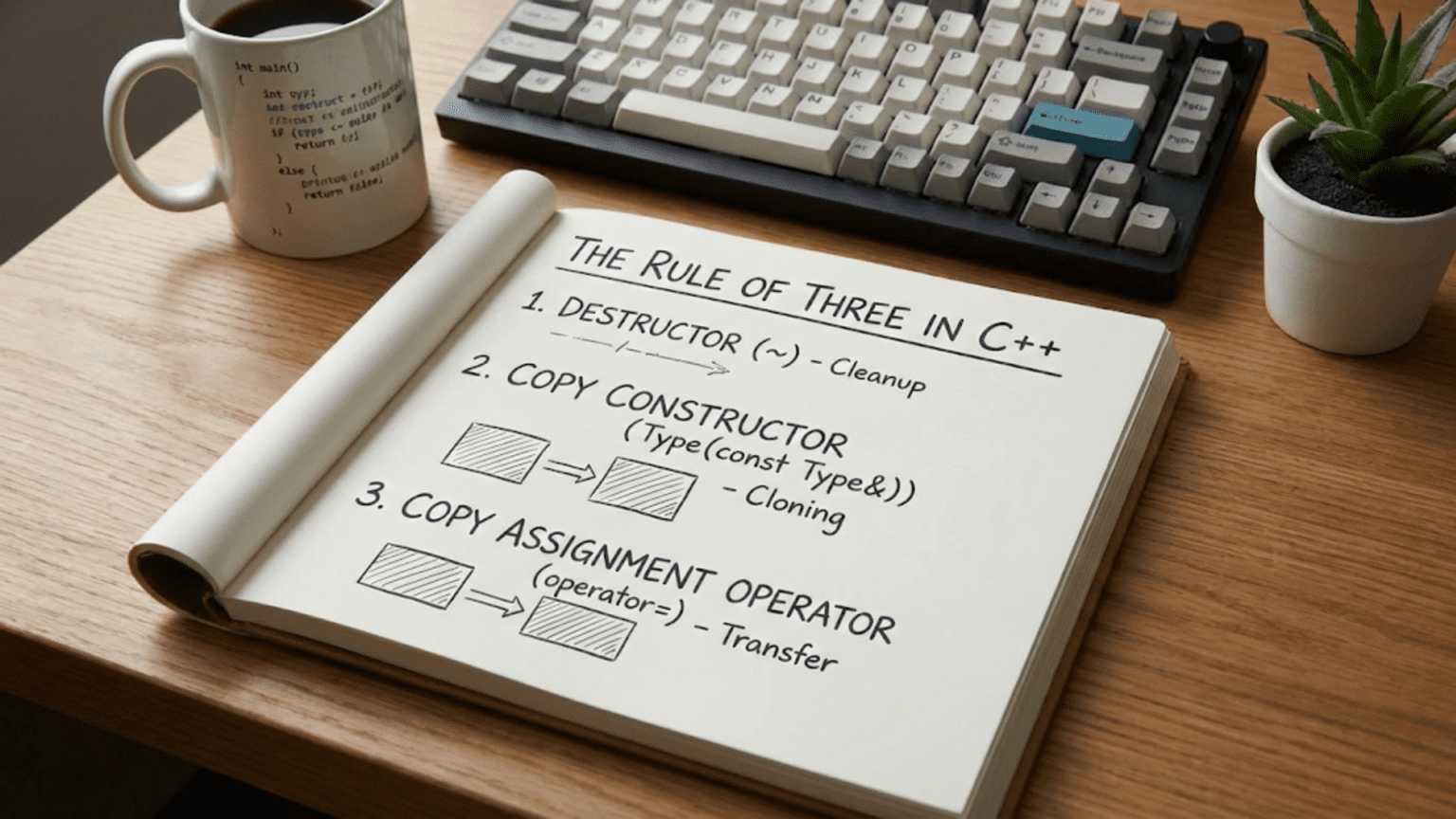

The Rule of Three in C++ states that if a class requires a user-defined destructor, copy constructor, or copy assignment operator, it almost certainly requires all three. This rule applies to classes that manage resources (like dynamic memory, file handles, or network connections), ensuring proper resource management, preventing memory leaks, avoiding double deletion, and maintaining object integrity during copying and assignment.

Introduction: The Trinity of Resource Management

The Rule of Three is one of C++’s most important design principles, yet it’s frequently misunderstood or ignored by beginners. This rule exists because of a fundamental issue in C++: when your class manages resources, the compiler-generated special member functions don’t know how to handle those resources correctly. The default implementations work fine for simple classes, but they fail catastrophically for classes with dynamic memory, file handles, or other resources that require special management.

Consider a class that allocates memory in its constructor. When you copy this object, what should happen? Should both objects share the same memory (dangerous), or should each have its own copy (safe)? When the object is destroyed, who frees the memory? If you don’t answer these questions explicitly by implementing the Rule of Three, the compiler answers them for you—and its answers often lead to crashes, memory leaks, and data corruption.

The Rule of Three connects three special member functions that work together to manage an object’s lifecycle: the destructor (cleanup when destroyed), the copy constructor (create a copy), and the copy assignment operator (copy to existing object). If you need to customize any one of these, you almost certainly need to customize all three. They’re interconnected—get one wrong, and the others won’t save you.

This comprehensive guide will teach you everything about the Rule of Three: why it exists, when to apply it, how to implement each component correctly, common mistakes to avoid, and modern alternatives. You’ll see practical examples demonstrating both correct and incorrect implementations, understanding not just the “what” but the “why” behind this fundamental rule.

Understanding the Rule of Three

The Rule of Three states: If a class requires one of the following, it likely requires all three:

- Destructor – Cleans up resources when object is destroyed

- Copy Constructor – Creates new object as copy of existing object

- Copy Assignment Operator – Copies one existing object to another

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class SimpleResource {

private:

int* data;

int size;

public:

// Constructor

SimpleResource(int s) : size(s) {

data = new int[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = i;

}

cout << "Constructor: Allocated " << size << " integers at " << data << endl;

}

// Destructor (1 of 3)

~SimpleResource() {

cout << "Destructor: Deleting array at " << data << endl;

delete[] data;

}

// Copy Constructor (2 of 3)

SimpleResource(const SimpleResource& other) : size(other.size) {

data = new int[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

cout << "Copy Constructor: Copied " << size << " integers from "

<< other.data << " to " << data << endl;

}

// Copy Assignment Operator (3 of 3)

SimpleResource& operator=(const SimpleResource& other) {

cout << "Copy Assignment: Copying from " << other.data

<< " to " << data << endl;

// Check for self-assignment

if (this == &other) {

cout << "Self-assignment detected" << endl;

return *this;

}

// Delete old data

delete[] data;

// Copy size and allocate new data

size = other.size;

data = new int[size];

// Copy elements

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

return *this;

}

void display() const {

cout << "Data at " << data << ": ";

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

cout << data[i] << " ";

}

cout << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Creating original object ===" << endl;

SimpleResource obj1(5);

obj1.display();

cout << "\n=== Copy construction ===" << endl;

SimpleResource obj2 = obj1; // Calls copy constructor

obj2.display();

cout << "\n=== Copy assignment ===" << endl;

SimpleResource obj3(3);

obj3.display();

obj3 = obj1; // Calls copy assignment operator

obj3.display();

cout << "\n=== Self-assignment test ===" << endl;

obj3 = obj3; // Should handle gracefully

cout << "\n=== End of main (destructors will run) ===" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- SimpleResource class: Manages dynamic integer array (resource requiring cleanup)

- data pointer: Points to dynamically allocated memory

- Constructor allocates: Uses

new int[size]to create array - Destructor (Rule 1): Frees memory with

delete[] datawhen object destroyed - Copy constructor (Rule 2): Creates deep copy with new memory allocation

- Deep copy process: Allocates new array, copies all elements individually

- Copy assignment (Rule 3): Handles copying to already-existing object

- Self-assignment check:

if (this == &other)prevents deleting memory we’re copying - Delete old data: Frees existing memory before allocating new

- Allocate and copy: Same deep copy process as copy constructor

- *Return this: Enables chaining assignments like

a = b = c - Three work together: Destructor cleans up what constructors/assignment create

- All three needed: If any one is missing, program has bugs

- Safe copying: Each object owns independent memory

Output:

=== Creating original object ===

Constructor: Allocated 5 integers at 0x...

Data at 0x...: 0 1 2 3 4

=== Copy construction ===

Copy Constructor: Copied 5 integers from 0x... to 0x...

Data at 0x...: 0 1 2 3 4

=== Copy assignment ===

Constructor: Allocated 3 integers at 0x...

Data at 0x...: 0 1 2

Copy Assignment: Copying from 0x... to 0x...

Data at 0x...: 0 1 2 3 4

=== Self-assignment test ===

Copy Assignment: Copying from 0x... to 0x...

Self-assignment detected

=== End of main (destructors will run) ===

Destructor: Deleting array at 0x...

Destructor: Deleting array at 0x...

Destructor: Deleting array at 0x...Why the Rule Exists: The Problem with Defaults

When you don’t implement the Rule of Three, C++ generates default versions. For resource-managing classes, these defaults cause serious problems.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// BAD EXAMPLE - Violates Rule of Three

class BadResource {

private:

int* data;

public:

BadResource(int value) {

data = new int(value);

cout << "[BAD] Allocated at " << data << ", value = " << *data << endl;

}

// Only destructor provided, missing copy constructor and assignment

~BadResource() {

cout << "[BAD] Deleting at " << data << ", value = " << *data << endl;

delete data;

}

// Compiler generates default copy constructor (shallow copy)

// Compiler generates default assignment operator (shallow copy)

int getValue() const { return *data; }

void setValue(int v) { *data = v; }

int* getAddress() const { return data; }

};

// GOOD EXAMPLE - Follows Rule of Three

class GoodResource {

private:

int* data;

public:

GoodResource(int value) {

data = new int(value);

cout << "[GOOD] Allocated at " << data << ", value = " << *data << endl;

}

// Destructor

~GoodResource() {

cout << "[GOOD] Deleting at " << data << ", value = " << *data << endl;

delete data;

}

// Copy constructor (deep copy)

GoodResource(const GoodResource& other) {

data = new int(*other.data);

cout << "[GOOD] Copy constructed at " << data

<< " from " << other.data << endl;

}

// Copy assignment operator (deep copy)

GoodResource& operator=(const GoodResource& other) {

if (this != &other) {

delete data;

data = new int(*other.data);

cout << "[GOOD] Copy assigned to " << data

<< " from " << other.data << endl;

}

return *this;

}

int getValue() const { return *data; }

void setValue(int v) { *data = v; }

int* getAddress() const { return data; }

};

int main() {

cout << "=== BAD EXAMPLE (Rule of Three violated) ===" << endl;

{

BadResource bad1(100);

BadResource bad2 = bad1; // Shallow copy!

cout << "\nAddresses:" << endl;

cout << "bad1: " << bad1.getAddress() << endl;

cout << "bad2: " << bad2.getAddress() << endl;

cout << "Same address? " << (bad1.getAddress() == bad2.getAddress() ? "YES - PROBLEM!" : "NO") << endl;

cout << "\nModifying bad2..." << endl;

bad2.setValue(999);

cout << "bad1 value: " << bad1.getValue() << " (affected!)" << endl;

cout << "bad2 value: " << bad2.getValue() << endl;

cout << "\nLeaving scope - DOUBLE DELETE CRASH!" << endl;

} // Both destructors delete same memory - undefined behavior!

cout << "\n=== GOOD EXAMPLE (Rule of Three followed) ===" << endl;

{

GoodResource good1(100);

GoodResource good2 = good1; // Deep copy!

cout << "\nAddresses:" << endl;

cout << "good1: " << good1.getAddress() << endl;

cout << "good2: " << good2.getAddress() << endl;

cout << "Same address? " << (good1.getAddress() == good2.getAddress() ? "YES" : "NO - SAFE!") << endl;

cout << "\nModifying good2..." << endl;

good2.setValue(999);

cout << "good1 value: " << good1.getValue() << " (not affected)" << endl;

cout << "good2 value: " << good2.getValue() << endl;

cout << "\nLeaving scope - safe destruction" << endl;

} // Each destructor deletes its own memory - safe!

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- BadResource class: Only implements destructor, violating Rule of Three

- Default copy constructor: Compiler generates shallow copy (copies pointer value)

- Shallow copy danger: bad1.data and bad2.data point to same memory

- Shared memory: Modifying through one object affects the other

- Double deletion: Both destructors try to delete same memory address

- Undefined behavior: Program may crash, corrupt memory, or appear to work

- GoodResource class: Implements all three components of Rule of Three

- Deep copy in constructor: Allocates new memory, copies value

- Deep copy in assignment: Deletes old, allocates new, copies value

- Independent memory: good1.data and good2.data point to different addresses

- Safe modifications: Changing one doesn’t affect the other

- Safe destruction: Each destructor deletes different memory

- Address comparison: Output shows whether objects share memory

- Visual proof: Good example shows different addresses, bad shows same

Output (bad example may crash):

=== BAD EXAMPLE (Rule of Three violated) ===

[BAD] Allocated at 0x..., value = 100

Addresses:

bad1: 0x...

bad2: 0x... (SAME ADDRESS!)

Same address? YES - PROBLEM!

Modifying bad2...

bad1 value: 999 (affected!)

bad2 value: 999

Leaving scope - DOUBLE DELETE CRASH!

[BAD] Deleting at 0x..., value = 999

[BAD] Deleting at 0x..., value = 999 (CRASH - double delete!)

=== GOOD EXAMPLE (Rule of Three followed) ===

[GOOD] Allocated at 0x..., value = 100

[GOOD] Copy constructed at 0x... from 0x...

Addresses:

good1: 0x...

good2: 0x... (DIFFERENT ADDRESS!)

Same address? NO - SAFE!

Modifying good2...

good1 value: 100 (not affected)

good2 value: 999

Leaving scope - safe destruction

[GOOD] Deleting at 0x..., value = 999

[GOOD] Deleting at 0x..., value = 100Implementing Each Component Correctly

Let’s examine each component of the Rule of Three in detail with a practical String class:

#include <iostream>

#include <cstring>

using namespace std;

class MyString {

private:

char* str;

int length;

public:

// Regular constructor

MyString(const char* s = "") {

length = strlen(s);

str = new char[length + 1];

strcpy(str, s);

cout << "Constructor: Created \"" << str << "\" at " << static_cast<void*>(str) << endl;

}

// COMPONENT 1: Destructor

~MyString() {

cout << "Destructor: Deleting \"" << str << "\" at " << static_cast<void*>(str) << endl;

delete[] str;

str = nullptr; // Good practice: prevent use after delete

}

// COMPONENT 2: Copy Constructor

MyString(const MyString& other) {

cout << "Copy Constructor: Copying \"" << other.str << "\"" << endl;

// Copy length

length = other.length;

// Allocate new memory

str = new char[length + 1];

// Copy string content

strcpy(str, other.str);

cout << " Created new copy at " << static_cast<void*>(str) << endl;

}

// COMPONENT 3: Copy Assignment Operator

MyString& operator=(const MyString& other) {

cout << "Assignment Operator: Assigning \"" << other.str

<< "\" to \"" << str << "\"" << endl;

// Step 1: Check for self-assignment

if (this == &other) {

cout << " Self-assignment detected, skipping" << endl;

return *this;

}

// Step 2: Delete old data

delete[] str;

// Step 3: Copy new data (same as copy constructor)

length = other.length;

str = new char[length + 1];

strcpy(str, other.str);

cout << " Assignment complete, new address: " << static_cast<void*>(str) << endl;

// Step 4: Return *this for chaining

return *this;

}

// Utility methods

const char* c_str() const { return str; }

int getLength() const { return length; }

void append(const char* s) {

int newLength = length + strlen(s);

char* newStr = new char[newLength + 1];

strcpy(newStr, str);

strcat(newStr, s);

delete[] str;

str = newStr;

length = newLength;

}

void display() const {

cout << " String: \"" << str << "\" (length " << length

<< ") at " << static_cast<void*>(str) << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== 1. Constructor ===" << endl;

MyString s1("Hello");

s1.display();

cout << "\n=== 2. Copy Constructor ===" << endl;

MyString s2 = s1; // or MyString s2(s1);

s2.display();

cout << "\n=== 3. Copy Assignment ===" << endl;

MyString s3("World");

s3.display();

cout << "Now assigning s1 to s3..." << endl;

s3 = s1;

s3.display();

cout << "\n=== 4. Self-Assignment Test ===" << endl;

s3 = s3;

s3.display();

cout << "\n=== 5. Chained Assignment ===" << endl;

MyString s4("A"), s5("B");

s4 = s5 = s1; // Right-to-left: s5 = s1, then s4 = s5

s4.display();

s5.display();

cout << "\n=== 6. Independence Test ===" << endl;

s2.append(" World");

cout << "After appending to s2:" << endl;

s1.display(); // Should be unchanged

s2.display(); // Should be modified

cout << "\n=== 7. Destruction (automatic) ===" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- MyString class: Manages dynamic character array (C-style string)

- Regular constructor: Allocates memory, copies initial string

- Destructor implementation: Frees allocated memory, sets pointer to nullptr

- nullptr after delete: Prevents accidental use of freed memory

- Copy constructor signature:

MyString(const MyString& other) - Copy constructor steps: Copy length, allocate new memory, copy content

- strcpy usage: Copies string including null terminator

- Assignment operator signature: Returns

MyString&for chaining - Assignment step 1: Self-assignment check crucial to avoid deleting source

- Assignment step 2: Delete old string to prevent memory leak

- Assignment step 3: Allocate and copy (same as copy constructor)

- Assignment step 4: Return

*thisto enablea = b = csyntax - Independence verification: Modifying s2 doesn’t affect s1

- Automatic destruction: Destructors called when objects go out of scope

- Safe cleanup: Each object deletes its own memory

Output:

=== 1. Constructor ===

Constructor: Created "Hello" at 0x...

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

=== 2. Copy Constructor ===

Copy Constructor: Copying "Hello"

Created new copy at 0x...

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

=== 3. Copy Assignment ===

Constructor: Created "World" at 0x...

String: "World" (length 5) at 0x...

Now assigning s1 to s3...

Assignment Operator: Assigning "Hello" to "World"

Assignment complete, new address: 0x...

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

=== 4. Self-Assignment Test ===

Assignment Operator: Assigning "Hello" to "Hello"

Self-assignment detected, skipping

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

=== 5. Chained Assignment ===

Constructor: Created "A" at 0x...

Constructor: Created "B" at 0x...

Assignment Operator: Assigning "Hello" to "B"

Assignment complete, new address: 0x...

Assignment Operator: Assigning "Hello" to "A"

Assignment complete, new address: 0x...

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

=== 6. Independence Test ===

After appending to s2:

String: "Hello" (length 5) at 0x...

String: "Hello World" (length 11) at 0x...

=== 7. Destruction (automatic) ===

Destructor: Deleting "Hello" at 0x...

Destructor: Deleting "Hello" at 0x...

Destructor: Deleting "Hello World" at 0x...

Destructor: Deleting "Hello" at 0x...

Destructor: Deleting "Hello" at 0x...Copy-and-Swap Idiom: An Elegant Alternative

The copy-and-swap idiom is a technique that implements the copy assignment operator in terms of the copy constructor and a swap function, providing strong exception safety.

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm> // for std::swap

using namespace std;

class SmartArray {

private:

int* data;

int size;

public:

// Constructor

SmartArray(int s = 0) : size(s) {

data = size > 0 ? new int[size] : nullptr;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = i * 10;

}

cout << "Constructor: Created array of size " << size << endl;

}

// Destructor

~SmartArray() {

cout << "Destructor: Deleting array of size " << size << endl;

delete[] data;

}

// Copy Constructor

SmartArray(const SmartArray& other) : size(other.size) {

data = size > 0 ? new int[size] : nullptr;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

cout << "Copy Constructor: Copied array of size " << size << endl;

}

// Swap function (member or friend)

void swap(SmartArray& other) noexcept {

cout << "Swapping arrays (size " << size << " <-> " << other.size << ")" << endl;

std::swap(data, other.data);

std::swap(size, other.size);

}

// Copy Assignment using Copy-and-Swap

SmartArray& operator=(SmartArray other) { // Note: pass by VALUE

cout << "Assignment Operator (copy-and-swap)" << endl;

swap(other); // Swap with the parameter

return *this;

// other (containing old data) will be destroyed automatically

}

void display() const {

cout << "Array (" << size << "): ";

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

cout << data[i] << " ";

}

cout << endl;

}

int getSize() const { return size; }

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Creating arrays ===" << endl;

SmartArray arr1(5);

arr1.display();

SmartArray arr2(3);

arr2.display();

cout << "\n=== Assignment using copy-and-swap ===" << endl;

arr2 = arr1; // Copy constructor creates temp, then swap

arr2.display();

cout << "\n=== Self-assignment ===" << endl;

arr2 = arr2; // Automatically safe with copy-and-swap

arr2.display();

cout << "\n=== End of main ===" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- SmartArray class: Manages dynamic integer array

- Standard destructor: Frees allocated memory

- Standard copy constructor: Deep copies array

- swap function: Efficiently exchanges data between two objects

- noexcept specification: Indicates swap won’t throw exceptions

- Copy-and-swap assignment: Takes parameter BY VALUE (not reference)

- Automatic copy: Passing by value creates copy via copy constructor

- Swap with copy: Exchange contents with the parameter copy

- Automatic cleanup: Parameter (containing old data) destroyed when function ends

- Self-assignment safety: Even

arr = arrworks correctly - Exception safety: If copy constructor throws, original object unchanged

- Code reuse: Assignment operator reuses copy constructor logic

- Simpler implementation: No explicit self-assignment check needed

- Strong guarantee: Either assignment succeeds completely or original unchanged

Output:

=== Creating arrays ===

Constructor: Created array of size 5

Array (5): 0 10 20 30 40

Constructor: Created array of size 3

Array (3): 0 10 20

=== Assignment using copy-and-swap ===

Copy Constructor: Copied array of size 5

Assignment Operator (copy-and-swap)

Swapping arrays (size 3 <-> 5)

Array (5): 0 10 20 30 40

Destructor: Deleting array of size 3

=== Self-assignment ===

Copy Constructor: Copied array of size 5

Assignment Operator (copy-and-swap)

Swapping arrays (size 5 <-> 5)

Array (5): 0 10 20 30 40

Destructor: Deleting array of size 5

=== End of main ===

Destructor: Deleting array of size 5

Destructor: Deleting array of size 5When to Apply the Rule of Three

The Rule of Three applies when your class manages resources. Here’s a decision guide:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

// CASE 1: No dynamic resources - Rule of Three NOT needed

class SimpleData {

private:

int value;

string name;

double price;

public:

SimpleData(int v, string n, double p) : value(v), name(n), price(p) {}

// No destructor needed - compiler default is fine

// No copy constructor needed - memberwise copy is fine

// No assignment operator needed - memberwise assignment is fine

void display() const {

cout << name << ": value=" << value << ", price=$" << price << endl;

}

};

// CASE 2: Dynamic resource - Rule of Three REQUIRED

class DynamicResource {

private:

int* data;

int size;

public:

DynamicResource(int s) : size(s) {

data = new int[size];

}

// MUST implement all three:

~DynamicResource() {

delete[] data;

}

DynamicResource(const DynamicResource& other) : size(other.size) {

data = new int[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

}

DynamicResource& operator=(const DynamicResource& other) {

if (this != &other) {

delete[] data;

size = other.size;

data = new int[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

}

return *this;

}

};

// CASE 3: STL containers - Rule of Three NOT needed

class UsesSTL {

private:

vector<int> numbers;

string text;

public:

UsesSTL(int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

numbers.push_back(i);

}

}

// STL containers handle their own memory

// Default copy, assignment, and destruction work correctly

};

// CASE 4: Multiple resources - Rule of Three REQUIRED

class MultipleResources {

private:

int* array;

char* name;

public:

MultipleResources(int size, const char* n) {

array = new int[size];

name = new char[strlen(n) + 1];

strcpy(name, n);

}

~MultipleResources() {

delete[] array;

delete[] name;

}

MultipleResources(const MultipleResources& other) {

// Must copy both resources

// ... implementation

}

MultipleResources& operator=(const MultipleResources& other) {

// Must handle both resources

// ... implementation

return *this;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Case 1: Simple data (no Rule of Three) ===" << endl;

SimpleData item1(42, "Widget", 19.99);

SimpleData item2 = item1; // Default copy works fine

item1.display();

item2.display();

cout << "\n=== Case 2: Dynamic resource (Rule of Three required) ===" << endl;

DynamicResource res1(5);

DynamicResource res2 = res1; // Uses implemented copy constructor

cout << "\n=== Case 3: STL containers (no Rule of Three) ===" << endl;

UsesSTL stl1(10);

UsesSTL stl2 = stl1; // STL handles copying

return 0;

}When to apply Rule of Three:

- Raw pointers to heap memory – ALWAYS apply

- File handles or network sockets – ALWAYS apply

- System resources (mutex, semaphore) – ALWAYS apply

- Plain old data (POD) types only – NOT needed

- STL containers only – NOT needed (they handle themselves)

- Mix of POD and STL – NOT needed

- Any raw pointer – ALWAYS apply

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Let’s examine frequent errors when implementing the Rule of Three:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// MISTAKE 1: Forgetting self-assignment check

class Mistake1 {

private:

int* data;

public:

Mistake1(int v) { data = new int(v); }

~Mistake1() { delete data; }

// WRONG: No self-assignment check

Mistake1& operator=(const Mistake1& other) {

delete data; // If other == this, we just deleted what we're about to copy!

data = new int(*other.data); // Accessing deleted memory!

return *this;

}

// CORRECT:

// Mistake1& operator=(const Mistake1& other) {

// if (this != &other) {

// delete data;

// data = new int(*other.data);

// }

// return *this;

// }

};

// MISTAKE 2: Not returning *this in assignment operator

class Mistake2 {

private:

int value;

public:

Mistake2(int v) : value(v) {}

// WRONG: Returns void

void operator=(const Mistake2& other) {

value = other.value;

// Can't chain: a = b = c won't work

}

// CORRECT: Returns reference

// Mistake2& operator=(const Mistake2& other) {

// value = other.value;

// return *this;

// }

};

// MISTAKE 3: Shallow copy in copy constructor

class Mistake3 {

private:

int* data;

public:

Mistake3(int v) { data = new int(v); }

~Mistake3() { delete data; }

// WRONG: Shallow copy

Mistake3(const Mistake3& other) {

data = other.data; // Both point to same memory!

}

// CORRECT: Deep copy

// Mistake3(const Mistake3& other) {

// data = new int(*other.data);

// }

};

// MISTAKE 4: Not making copy constructor parameter const

class Mistake4 {

private:

int value;

public:

Mistake4(int v) : value(v) {}

// WRONG: Parameter not const

Mistake4(Mistake4& other) { // Missing const

value = other.value;

other.value = 0; // Can accidentally modify source!

}

// CORRECT:

// Mistake4(const Mistake4& other) {

// value = other.value;

// // other.value = 0; // Error: can't modify const

// }

};

// MISTAKE 5: Forgetting to implement all three

class Mistake5 {

private:

int* data;

public:

Mistake5(int v) { data = new int(v); }

// Implemented destructor

~Mistake5() { delete data; }

// WRONG: Missing copy constructor and assignment operator

// Default shallow copies will cause double-delete!

// MUST ALSO IMPLEMENT:

// Mistake5(const Mistake5& other);

// Mistake5& operator=(const Mistake5& other);

};

// CORRECT IMPLEMENTATION

class Correct {

private:

int* data;

public:

Correct(int v) { data = new int(v); }

~Correct() { delete data; }

Correct(const Correct& other) {

data = new int(*other.data);

}

Correct& operator=(const Correct& other) {

if (this != &other) {

delete data;

data = new int(*other.data);

}

return *this;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "These examples show common mistakes." << endl;

cout << "The correct implementations are commented." << endl;

cout << "Always follow the Rule of Three completely!" << endl;

return 0;

}Common mistakes summary:

- No self-assignment check – Deletes memory before copying from it

- Wrong return type – Prevents chaining assignments

- Shallow copy – Multiple objects share same memory

- Non-const parameter – Allows accidental modification of source

- Implementing only some – Partial implementation causes bugs

- Not using initializer list – Less efficient, wrong order

- Memory leak in assignment – Forgetting to delete old memory

Modern C++: Rule of Five and Rule of Zero

Modern C++ introduces move semantics, extending the Rule of Three to the Rule of Five, and promotes the Rule of Zero.

#include <iostream>

#include <utility> // for std::move

using namespace std;

// Rule of Five: Add move constructor and move assignment

class ModernResource {

private:

int* data;

int size;

public:

ModernResource(int s) : size(s) {

data = new int[size];

cout << "Constructor: size=" << size << endl;

}

// 1. Destructor

~ModernResource() {

cout << "Destructor: size=" << size << endl;

delete[] data;

}

// 2. Copy Constructor

ModernResource(const ModernResource& other) : size(other.size) {

data = new int[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

cout << "Copy Constructor: size=" << size << endl;

}

// 3. Copy Assignment

ModernResource& operator=(const ModernResource& other) {

cout << "Copy Assignment" << endl;

if (this != &other) {

delete[] data;

size = other.size;

data = new int[size];

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

data[i] = other.data[i];

}

}

return *this;

}

// 4. Move Constructor (C++11)

ModernResource(ModernResource&& other) noexcept

: data(other.data), size(other.size) {

cout << "Move Constructor: size=" << size << endl;

other.data = nullptr; // Leave source in valid state

other.size = 0;

}

// 5. Move Assignment (C++11)

ModernResource& operator=(ModernResource&& other) noexcept {

cout << "Move Assignment" << endl;

if (this != &other) {

delete[] data;

data = other.data;

size = other.size;

other.data = nullptr;

other.size = 0;

}

return *this;

}

};

// Rule of Zero: Use existing resource managers

class RuleOfZero {

private:

vector<int> data; // STL container manages memory

string name; // STL string manages memory

public:

RuleOfZero(int size, string n) : data(size), name(n) {}

// No need to implement any of the five special functions!

// Compiler-generated versions work perfectly because

// all members manage their own resources

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Rule of Five Example ===" << endl;

ModernResource r1(10);

ModernResource r2 = r1; // Copy constructor

ModernResource r3 = std::move(r1); // Move constructor

ModernResource r4(5);

r4 = r2; // Copy assignment

r4 = std::move(r3); // Move assignment

cout << "\n=== Rule of Zero Example ===" << endl;

RuleOfZero z1(100, "First");

RuleOfZero z2 = z1; // Default copy works!

RuleOfZero z3 = std::move(z1); // Default move works!

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Rule of Five: Extends Rule of Three with move constructor and move assignment

- Move constructor: Transfers ownership instead of copying

- && syntax: Rvalue reference indicates move semantics

- noexcept: Promise not to throw exceptions (enables optimizations)

- Steal resources: Move constructor takes other’s data pointer

- Nullify source: Sets other.data to nullptr (source left in valid state)

- Move assignment: Similar to move constructor but for existing object

- Efficiency: Moving is much faster than copying for large resources

- Rule of Zero: Prefer using STL containers that manage their own memory

- No special functions: When all members manage themselves, defaults work

- Best practice: Favor Rule of Zero when possible

- Use STL: vector, string, etc. handle memory automatically

Output:

=== Rule of Five Example ===

Constructor: size=10

Copy Constructor: size=10

Move Constructor: size=10

Constructor: size=5

Copy Assignment

Move Assignment

=== Rule of Zero Example ===

Destructor: size=0

Destructor: size=10

Destructor: size=10

Destructor: size=10Conclusion: Mastering Resource Management

The Rule of Three is a fundamental principle in C++ that ensures proper resource management for classes that own resources. When you implement a destructor, copy constructor, or copy assignment operator, you’re taking responsibility for your class’s resource management—and that responsibility extends to all three functions working together correctly.

Key takeaways:

- The Rule of Three: destructor, copy constructor, copy assignment operator must all be implemented together

- Default implementations use shallow copying, dangerous for classes with pointers

- Deep copying ensures each object has independent resources

- Self-assignment check prevents destroying data you’re about to copy

- Copy-and-swap idiom provides elegant, exception-safe assignment

- Modern C++ extends this to Rule of Five (add move operations) or Rule of Zero (use STL containers)

- Apply Rule of Three whenever your class directly manages resources

- STL containers follow these rules internally, so using them simplifies your code

Understanding and correctly implementing the Rule of Three is essential for writing robust, bug-free C++ code. Get it wrong, and you’ll face crashes from double deletion, memory leaks from forgotten cleanup, or data corruption from shallow copying. Get it right, and your classes will be safe, efficient, and maintainable.

Remember: if you need one of the three, you need all three. Don’t leave resource management to chance—implement the Rule of Three completely and correctly, or better yet, follow the Rule of Zero by using STL containers that handle these details for you. Your future self (and your users) will thank you for the time invested in proper resource management.