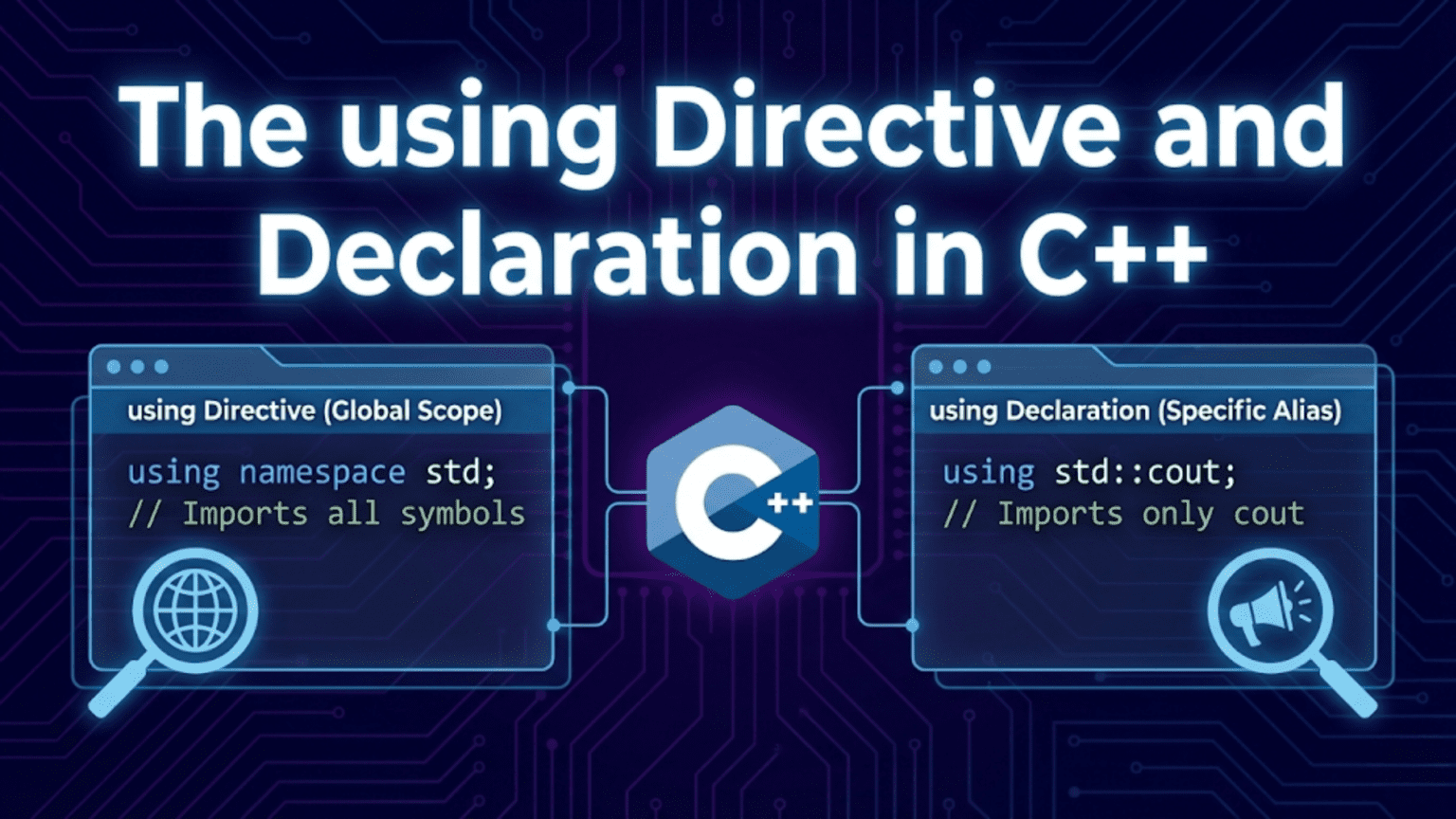

C++ provides two distinct using mechanisms: the using directive (using namespace std;) imports all names from a namespace into the current scope, which is convenient but risks name conflicts. The using declaration (using std::cout;) imports only a single specific name—safer, more explicit, and preferred in professional code. A third form, the using type alias (using Vector = std::vector<int>;), creates a readable synonym for a type—the modern replacement for typedef.

Introduction: Reducing Namespace Verbosity the Right Way

After learning about namespaces, you quickly run into a practical tension: namespaces prevent name collisions, but they also make code verbose. Writing std::vector<std::string> instead of vector<string>, or std::cout << std::endl instead of cout << endl, adds considerable noise to code that everyone already knows comes from the standard library.

The using keyword provides three mechanisms to address this verbosity without abandoning the benefits of namespaces: the using directive, the using declaration, and the using type alias. Each has a different scope of effect, a different level of risk, and appropriate use contexts.

Understanding the differences—and knowing which to use where—separates beginner C++ from production-quality C++. The using namespace std that appears in virtually every tutorial and textbook example is a deliberate simplification for teaching. In real codebases, especially headers, it causes serious maintenance problems. This guide explains why, what to use instead, and how to leverage using safely and expressively in all its forms.

This comprehensive guide covers the using directive, using declaration, and using type alias in depth: how each works, where each is appropriate, what can go wrong, and how they interact with inheritance, templates, and scope. Every concept is illustrated with practical, step-by-step examples.

The using Directive: Importing a Whole Namespace

The using directive makes all names from a namespace visible in the current scope without qualification.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <algorithm>

// ─── Without using directive ──────────────────────────────────

void withoutUsing() {

std::vector<std::string> names = {"Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"};

std::sort(names.begin(), names.end());

for (const std::string& name : names) {

std::cout << name << std::endl;

}

}

// ─── With using directive (namespace scope) ───────────────────

using namespace std; // Makes all std:: names visible

void withUsing() {

vector<string> names = {"Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"};

sort(names.begin(), names.end());

for (const string& name : names) {

cout << name << endl;

}

}

// ─── using directive in function scope (safer) ────────────────

void withLocalUsing() {

using namespace std; // Only active within this function

vector<int> nums = {5, 3, 1, 4, 2};

sort(nums.begin(), nums.end());

for (int n : nums) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// using namespace std no longer active after function ends

}

int main() {

cout << "=== Without using directive ===" << endl;

withoutUsing();

cout << "\n=== With using directive ===" << endl;

withUsing();

cout << "\n=== Local using directive in function ===" << endl;

withLocalUsing();

// At global scope, using namespace std is active

cout << "\n=== Global using namespace std in effect ===" << endl;

string s = "Hello from global using!";

cout << s << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Without using directive: Every standard library name must be fully qualified with

std:: - std::vectorstd::string: Both the container and element type need qualification

- std::sort, std::cout: All STL algorithm and I/O names require prefix

- using namespace std: Makes all ~1,800+ names in the std namespace visible without qualification

- vector<string> (no std::): After directive, names found without prefix — compiler looks in std

- How lookup works: Compiler searches current scope, then enclosing scopes, then using-namespace-d namespaces

- File-scope directive:

using namespace stdat global scope — active for entire file - Function-scope directive:

using namespace stdinside function body — active only within that function - Function scope is safer: Contamination limited to one function, not entire translation unit

- After function ends: using directive goes out of scope with the function’s

{} - Global directive danger: Any name you define that matches an std name causes ambiguity

- 1,800+ std names: std includes everything from

aborttozeta— many common names - Tutorial vs production:

using namespace stdfine for short examples, dangerous in real code - Three scopes: File scope (risky), function scope (acceptable), never in headers (forbidden)

Output:

=== Without using directive ===

Alice

Bob

Charlie

=== With using directive ===

Alice

Bob

Charlie

=== Local using directive in function ===

1 2 3 4 5

=== Global using namespace std in effect ===

Hello from global using!The Danger of using namespace in Headers

The most important rule: never put using namespace in a header file.

// ── BAD: my_utils.h (DON'T DO THIS) ──────────────────────────

/*

#pragma once

#include <string>

#include <vector>

using namespace std; // DANGER: infects every file that includes this header!

string processName(string name); // These look clean but are actually std::string

vector<int> getNumbers();

*/

// ── GOOD: my_utils.h ──────────────────────────────────────────

// #pragma once

// #include <string>

// #include <vector>

// std::string processName(std::string name); // Explicit qualification

// std::vector<int> getNumbers();

// ── The problem demonstrated ────────────────────────────────────

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// Simulated third-party header that pollutes namespace

namespace ThirdParty {

string connect(const string& host) {

return "connected to " + host;

}

int count = 0; // Oops — shadows any 'count' variable

}

// If ThirdParty's header had: using namespace ThirdParty;

// Then the next file to include it would see 'connect' and 'count' polluting scope

void demonstratePollution() {

// After: using namespace ThirdParty;

// These become ambiguous if std also has a 'count' (std::count algorithm)

using namespace ThirdParty; // Simulate pollution

// string result = connect("server"); // OK — ThirdParty::connect

// But now 'count' refers to ThirdParty::count not std::count!

cout << "=== Header pollution demonstration ===" << endl;

cout << "Problem: 'using namespace X' in a header means:" << endl;

cout << " Every file including that header gets ALL of X's names" << endl;

cout << " Users can't opt out — it's forced on them" << endl;

cout << " Name conflicts may appear far from the include line" << endl;

cout << " Debugging these conflicts is very difficult" << endl;

}

// ── Real-world conflict example ────────────────────────────────

namespace MyLib {

int distance(int a, int b) { return b - a; } // Custom distance function

}

void showConflict() {

using namespace std;

using namespace MyLib;

// int d = distance(3, 7); // AMBIGUOUS: std::distance or MyLib::distance?

// Compiler error: 'distance' is ambiguous

// Fix: explicit qualification

int d1 = MyLib::distance(3, 7);

int d2 = std::distance(nullptr, nullptr); // Needs iterators but shows syntax

cout << "\n=== Conflict resolution ===" << endl;

cout << "MyLib::distance(3, 7) = " << d1 << endl;

cout << "Must qualify to resolve ambiguity" << endl;

}

int main() {

demonstratePollution();

showConflict();

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Header pollution:

using namespace stdin a header forces all names onto every file that includes it - Cascading effect: If A.h includes B.h which has

using namespace X, A.h gets X’s names too - No opt-out: Users of your header cannot undo the

using namespace— it’s permanent - Source of subtle bugs: Name conflicts appear in the user’s file, not in the header — confusing

- ThirdParty::count shadows: Any code after

using namespace ThirdPartyseescountas ThirdParty’s - std::count algorithm conflict: std has

count()for containers — common collision point - MyLib::distance conflict: std has

std::distance()for iterators — another famous collision - Ambiguity error: Compiler refuses to compile when two namespaces both provide the same name

- Error location is misleading: Error appears where name is used, not where

usingis written - The fix: Always qualify or use using declarations for specific names

- Golden rule: Never

using namespacein headers — only in .cpp files, and even there, consider scope - std is huge: With 1,800+ names, even obscure ones can conflict —

stable_sort,fill,count - Professional standard: All major C++ style guides (Google, LLVM, ISOC++) ban

using namespacein headers - Tutorial exception: Teaching materials use it to reduce noise — understand it’s a simplification

Output:

=== Header pollution demonstration ===

Problem: 'using namespace X' in a header means:

Every file including that header gets ALL of X's names

Users can't opt out — it's forced on them

Name conflicts may appear far from the include line

Debugging these conflicts is very difficult

=== Conflict resolution ===

MyLib::distance(3, 7) = 4

Must qualify to resolve ambiguityThe using Declaration: Importing a Single Name

The using declaration imports exactly one name—a precise, safe alternative to the blanket directive.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <algorithm>

#include <map>

using std::cout; // Import only cout from std

using std::endl; // Import only endl

using std::string; // Import only string

// Everything else still needs std::

void demonstrateDeclaration() {

cout << "=== using declaration ===" << endl;

// 'string' is imported — no std:: needed

string name = "C++ Developer";

cout << "Name: " << name << endl;

// vector is NOT imported — still needs std::

std::vector<int> nums = {3, 1, 4, 1, 5};

std::sort(nums.begin(), nums.end());

cout << "Sorted: ";

for (int n : nums) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

}

// using declarations in function scope — very safe

void functionScopeDeclaration() {

using std::vector;

using std::sort;

using std::map;

cout << "\n=== Function-scope using declarations ===" << endl;

vector<string> words = {"banana", "apple", "cherry"};

sort(words.begin(), words.end());

cout << "Sorted words: ";

for (const string& w : words) cout << w << " ";

cout << endl;

map<string, int> freq;

for (const string& w : words) freq[w]++;

cout << "Frequencies:" << endl;

for (const auto& [word, count] : freq) {

cout << " " << word << ": " << count << endl;

}

// vector, sort, map go out of scope here

}

// Comparison: declaration vs directive

void comparison() {

cout << "\n=== Declaration vs Directive ===" << endl;

// using declaration — only 'cout' imported

{

using std::cout;

cout << "using declaration: only cout" << endl;

// string s = "test"; // Error: string not imported

}

// using directive — everything imported

{

using namespace std;

cout << "using directive: all of std" << endl;

string s = "imported too";

cout << s << endl;

}

}

int main() {

demonstrateDeclaration();

functionScopeDeclaration();

comparison();

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- using std::cout: Imports exactly one name —

cout— from the std namespace - Three declarations:

using std::cout,using std::endl,using std::string— each imports one name - Everything else needs std::

std::vector,std::sortstill require qualification - Explicit inventory: Reading the using declarations at the top tells you exactly which std names are used

- Documentation value:

using std::stringat file top communicates “this file uses std::string” - No surprise names: Only the explicitly declared names are available without std::

- Function-scope declarations: Using declarations inside a function — even safer, limited to that scope

- vector, sort, map imported locally: After the function ends, these aliases disappear

- scope exit: The imported names go out of scope with the function’s

}— no pollution - Direct comparison: Scope block shows that declaration only brings cout; directive brings everything

- string not imported in declaration block:

string s = "test"would fail in declaration-only block - import precision: Using declaration is surgical — you control exactly what enters scope

- Preferred in .cpp files: Acceptable to use at file scope in .cpp files — still cleaner than directive

- Never in headers: Same rule as directive — using declarations in headers also cause pollution

Output:

=== using declaration ===

Name: C++ Developer

Sorted: 1 1 3 4 5

=== Function-scope using declarations ===

Sorted words: apple banana cherry

Frequencies:

apple: 1

banana: 1

cherry: 1

=== Declaration vs Directive ===

using declaration: only cout

using directive: all of std

imported toousing Type Aliases: Replacing typedef

The modern using syntax for type aliases is more readable and more powerful than the old typedef.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <map>

#include <functional>

#include <memory>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// ── Old typedef syntax ────────────────────────────────────────

typedef int Meters;

typedef double Kilograms;

typedef vector<int> IntList;

typedef map<string,int> StringToInt;

// Typedef with function pointer — very confusing syntax

typedef void (*Callback)(int, const string&);

// ── Modern using syntax — same effect, much clearer ───────────

using MetersU = int;

using KilogramsU = double;

using IntListU = vector<int>;

using StringToIntU = map<string, int>;

// using with function pointer — readable

using CallbackU = void(*)(int, const string&);

// using with std::function — even better

using EventHandler = function<void(int, const string&)>;

// ── Template alias — ONLY possible with using, not typedef ────

template <typename T>

using Vec = vector<T>; // Vec<int>, Vec<string>, etc.

template <typename K, typename V>

using Dict = map<K, V>; // Dict<string, int>, etc.

template <typename T>

using SharedPtr = shared_ptr<T>; // Shorter alias for shared_ptr

// ── Using for complex nested types ────────────────────────────

using Matrix = vector<vector<double>>;

using IntPair = pair<int, int>;

using Graph = map<int, vector<int>>;

void callback_impl(int code, const string& msg) {

cout << " Callback: code=" << code << " msg=" << msg << endl;

}

int main() {

cout << "=== typedef vs using — basic types ===" << endl;

Meters distance = 100;

MetersU distU = 100;

cout << "Both: " << distance << " meters == " << distU << " meters" << endl;

cout << "\n=== using with containers ===" << endl;

IntListU numbers = {5, 3, 1, 4, 2};

cout << "IntListU size: " << numbers.size() << endl;

StringToIntU scores = {{"Alice", 95}, {"Bob", 82}};

cout << "StringToIntU scores:" << endl;

for (const auto& [name, score] : scores) {

cout << " " << name << ": " << score << endl;

}

cout << "\n=== Function type aliases ===" << endl;

Callback oldStyle = callback_impl;

CallbackU newStyle = callback_impl;

EventHandler handler = callback_impl;

oldStyle(1, "old typedef");

newStyle(2, "using alias");

handler(3, "EventHandler");

cout << "\n=== Template aliases (only with using) ===" << endl;

Vec<int> vi = {1, 2, 3};

Vec<string> vs = {"one", "two", "three"};

Dict<string, int> d = {{"a", 1}, {"b", 2}};

cout << "Vec<int>: ";

for (int n : vi) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

cout << "Vec<string>: ";

for (const string& s : vs) cout << s << " ";

cout << endl;

cout << "Dict size: " << d.size() << endl;

cout << "\n=== Complex type aliases ===" << endl;

Matrix mat = {{1.0, 2.0, 3.0}, {4.0, 5.0, 6.0}};

cout << "Matrix[0][2] = " << mat[0][2] << endl;

Graph g;

g[0] = {1, 2, 3};

g[1] = {2, 3};

cout << "Graph node 0 neighbors: ";

for (int n : g[0]) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- typedef int Meters: Old syntax — type comes before alias name, hard to read for complex types

- using MetersU = int: New syntax — alias name on left, type on right — consistent, readable

- Same semantic effect: Both create a synonym — MetersU and int are interchangeable

- typedef function pointer:

typedef void (*Callback)(int, const string&)— the*Callbackinside makes it confusing - using function pointer:

using CallbackU = void(*)(int, const string&)— alias = type, clear and consistent - std::function alias:

using EventHandler = function<void(int, const string&)>— works with lambdas and functors - Template alias:

template<typename T> using Vec = vector<T>— IMPOSSIBLE with typedef - Vec<int>, Vec<string>: Template alias parameterized — creates specialized versions

- Dict<K, V>: Two-parameter template alias — shortens common map declarations

- SharedPtr<T>: Alias for shared_ptr — common in codebases to reduce verbosity

- Matrix: Complex nested type alias —

vector<vector<double>>becomes readableMatrix - Graph:

map<int, vector<int>>is common for adjacency lists — alias makes intent clear - Alias is transparent: Compiler treats

Vec<int>exactly asvector<int>— no overhead - Documentation through naming:

Matrixcommunicates purpose;vector<vector<double>>communicates implementation

Output:

=== typedef vs using — basic types ===

Both: 100 meters == 100 meters

=== using with containers ===

IntListU size: 5

StringToIntU scores:

Alice: 95

Bob: 82

=== Function type aliases ===

Callback: code=1 msg=old typedef

Callback: code=2 msg=using alias

Callback: code=3 msg=EventHandler

=== Template aliases (only with using) ===

Vec<int>: 1 2 3

Vec<string>: one two three

Dict size: 2

=== Complex type aliases ===

Matrix[0][2] = 3

Graph node 0 neighbors: 1 2 3using in Class Inheritance

The using declaration in classes serves a specialized purpose: bringing base class members into derived class scope.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Animal {

public:

void eat() { cout << "Animal eating" << endl; }

void sleep() { cout << "Animal sleeping" << endl; }

void breathe() { cout << "Animal breathing" << endl; }

// Overloaded functions

void speak() { cout << "Animal speaks (generic)" << endl; }

void speak(const string& language) {

cout << "Animal speaks " << language << endl;

}

};

class Dog : public Animal {

public:

// using declaration: bring Animal::eat into Dog's scope

using Animal::eat; // Re-expose as public

using Animal::sleep;

// Override speak — but bring ALL overloads of Animal::speak too

void speak() override { cout << "Dog: Woof!" << endl; }

using Animal::speak; // Also expose Animal::speak(const string&)

void fetch() { cout << "Dog fetching!" << endl; }

};

class Cat : public Animal {

private:

using Animal::breathe; // Change accessibility: breathe is now private in Cat

public:

void speak() { cout << "Cat: Meow!" << endl; }

void purr() { cout << "Cat purring" << endl; }

};

// Bringing constructor from base class

class Shape {

public:

double x, y;

Shape(double x, double y) : x(x), y(y) {

cout << "Shape(" << x << "," << y << ")" << endl;

}

Shape(const string& name) : x(0), y(0) {

cout << "Shape(name=" << name << ")" << endl;

}

};

class Circle : public Shape {

public:

double radius;

// Inherit ALL Shape constructors — no need to write delegation manually

using Shape::Shape;

Circle(double x, double y, double r) : Shape(x, y), radius(r) {

cout << "Circle(" << x << "," << y << ", r=" << r << ")" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

cout << "=== using in class inheritance ===" << endl;

Dog dog;

dog.eat(); // From Animal via using

dog.sleep(); // From Animal via using

dog.speak(); // Dog's own override

dog.speak("English"); // Animal's overload, exposed via using Animal::speak

cout << endl;

Cat cat;

cat.speak();

cat.purr();

// cat.breathe(); // ERROR: breathe is private in Cat

cout << "\n=== Inheriting constructors ===" << endl;

Circle c1(3.0, 4.0, 5.0); // Circle's own constructor

Circle c2(1.0, 2.0); // Shape(double, double) — inherited!

Circle c3("MyCircle"); // Shape(string) — inherited!

cout << "\n=== Why use in inheritance? ===" << endl;

cout << "1. Expose specific base members at different access level" << endl;

cout << "2. Bring all overloads of a base function when overriding one" << endl;

cout << "3. Inherit constructors without manually delegating each one" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- using Animal::eat: Brings Animal::eat into Dog’s public section — ensures it stays public

- Public inheritance: Members are public by default in public inheritance, so this is mainly documentation here

- Override hides all overloads: When Dog overrides

speak(), it hides ALL Animal::speak overloads - using Animal::speak: After overriding speak(), this restores access to the string overload

- Without using:

dog.speak("English")would fail — the string overload is hidden by override - Cat makes breathe private:

using Animal::breathein private section changes accessibility - cat.breathe() fails: Even though Animal::breathe is public, Cat makes it private

- Accessibility change: using declaration in private/protected section reduces access

- using Shape::Shape: Inherits ALL of Shape’s constructors into Circle

- c2 uses Shape(double,double): Circle doesn’t define this constructor — inherited from Shape

- c3 uses Shape(string): String constructor also inherited — zero boilerplate

- Without using: Would need to write

Circle(double x, double y) : Shape(x, y) {}etc. - Inheriting constructors (C++11): Feature specifically enabled by

using Base::Base;syntax - Own constructor coexists: Circle’s own 3-arg constructor works alongside inherited ones

Output:

=== using in class inheritance ===

Animal eating

Animal sleeping

Dog: Woof!

Animal speaks English

Cat: Meow!

Cat purring

=== Inheriting constructors ===

Shape(3,4)

Circle(3,4, r=5)

Shape(1,2)

Shape(name=MyCircle)

=== Why use in inheritance? ===

1. Expose specific base members at different access level

2. Bring all overloads of a base function when overriding one

3. Inherit constructors without manually delegating each oneScope Rules and Lookup Interaction

Understanding how using interacts with scope and name lookup prevents subtle bugs.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

namespace A {

void greet() { cout << "A::greet()" << endl; }

int value = 10;

}

namespace B {

void greet() { cout << "B::greet()" << endl; }

int value = 20;

}

void scopeDemo() {

cout << "=== Scope and shadowing ===" << endl;

// Outer scope: using A

using namespace A;

greet(); // A::greet

cout << "value: " << value << endl; // A::value

{

// Inner scope: using B

using namespace B;

// greet(); // AMBIGUOUS — A and B both visible!

// cout << value; // AMBIGUOUS — A and B both visible!

// Must qualify when ambiguous

A::greet();

B::greet();

cout << "A::value=" << A::value

<< " B::value=" << B::value << endl;

}

// Back to outer scope — only A in directive

greet(); // A::greet again (B's directive ended)

}

void declarationVsDirectiveScope() {

cout << "\n=== Declaration survives inner scope ===" << endl;

using A::greet; // Declaration: specific name imported

greet(); // A::greet — works

{

// Inner block: a local 'greet' shadows the using declaration

auto greet = []{ cout << "Local lambda greet" << endl; };

greet(); // Local lambda — shadows A::greet

}

greet(); // A::greet restored — local went out of scope

}

void lookupOrder() {

cout << "\n=== Lookup order ===" << endl;

// C++ name lookup order:

// 1. Current block scope

// 2. Enclosing block scopes

// 3. Namespace scope (including using directives)

// 4. Global scope

int count = 99; // Local variable

using namespace std;

// std has std::count() algorithm

// But local 'count' variable is found first!

cout << "Local count: " << count << endl;

// std::count is still reachable by explicit qualification

// cout << count_if(...); // std::count_if still accessible

}

int main() {

scopeDemo();

declarationVsDirectiveScope();

lookupOrder();

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Outer using namespace A: Makes A::greet and A::value visible without qualification

- Inner using namespace B: Both A and B are now in scope — creates potential ambiguity

- Ambiguous greet(): Compiler sees both A::greet and B::greet — refuses to guess, issues error

- Must qualify in ambiguous scope: A::greet() and B::greet() work — explicit beats lookup

- Inner scope ends: After

}, using namespace B is gone — A::greet is unambiguous again - using declaration survives shadowing:

using A::greetimports the name into scope - Local lambda shadows: Local variable named

greettakes priority over using declaration - Lookup order: Local scope → enclosing scopes → namespace — local wins

- After inner scope exits: Local lambda gone, using declaration’s greet() visible again

- Name lookup is hierarchical: Innermost scope checked first — stops at first match found

- Local count = 99: Declared in function scope — found before std’s count

- std::count hidden: Local variable name shadows it — std::count still accessible by qualification

- Key insight: using directive/declaration loses to locally declared names of same name

- Practical rule: Be careful naming local variables the same as imported names — confusing bugs

Output:

=== Scope and shadowing ===

A::greet()

value: 10

A::greet()

B::greet()

A::value=10 B::value=20

A::greet()

=== Declaration survives inner scope ===

A::greet()

Local lambda greet

A::greet()

=== Lookup order ===

Local count: 99Comparison Table

| Feature | Syntax | Scope | Risk | Best Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| using directive | using namespace std; | Brings ALL names | High — conflicts likely | Avoid in headers; OK in .cpp function scope |

| using declaration | using std::cout; | Brings ONE name | Low — explicit | Preferred for .cpp files |

| Type alias | using T = long_type; | Current scope | None | Always prefer over typedef |

| Template alias | template<> using ... | Current scope | None | Shortening template types |

| Inheritance using | using Base::member; | Class scope | Low | Restoring overloads, changing access, inheriting constructors |

Best Practices Consolidated

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <memory>

// ── HEADER FILE (my_module.h) — strict rules ──────────────────

// ✅ Always qualify in headers

// void process(std::vector<std::string>& data);

// ✅ Type aliases in headers are fine

// using StringList = std::vector<std::string>;

// ❌ Never using directive in headers

// using namespace std; // NEVER

// ❌ Never using declaration of std names in headers

// using std::string; // Avoid — leaks into every includer

// ── SOURCE FILE (my_module.cpp) — more flexibility ────────────

// ✅ using declarations at top of .cpp (not headers)

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

using std::string;

using std::vector;

// ✅ Type aliases for readability

using StringList = vector<string>;

using IntMatrix = vector<vector<int>>;

int main() {

cout << "=== Best Practices Summary ===" << endl;

// ✅ Type alias improves readability

StringList names = {"Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"};

cout << "Names count: " << names.size() << endl;

IntMatrix matrix = {{1,2,3},{4,5,6},{7,8,9}};

cout << "Matrix[1][2] = " << matrix[1][2] << endl;

cout << "\n=== Rules to live by ===" << endl;

cout << "1. NEVER using namespace in headers" << endl;

cout << "2. PREFER using declarations over directives" << endl;

cout << "3. PREFER using over typedef for type aliases" << endl;

cout << "4. LIMIT using directives to function scope when needed" << endl;

cout << "5. USE template aliases (using) for generic code" << endl;

cout << "6. IN classes: use 'using Base::member' to manage overloads" << endl;

cout << "7. QUALIFY std:: in all header files always" << endl;

// ✅ using in function scope — contained and clean

auto process = [](const StringList& list) {

using std::for_each;

for_each(list.begin(), list.end(),

[](const string& s){ cout << " Processing: " << s << endl; });

};

process(names);

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Headers always qualify:

std::vector<std::string>— no shortcuts in public interfaces - Type aliases in headers are OK:

using StringList = std::vector<std::string>— no pollution - Never directive in headers: Enforced by every major C++ style guide

- using declarations in .cpp: Acceptable at file scope in implementation files

- Documentation value:

using std::cout; using std::string;at top of .cpp lists dependencies - Type alias improves expressiveness:

StringListcommunicates intent;vector<string>communicates implementation - IntMatrix:

vector<vector<int>>is verbose and hides purpose — alias adds clarity - using in lambda: Function-scope using declarations inside lambdas — cleanest possible scope

- for_each imported locally: Lambda’s using std::for_each disappears when lambda body ends

- Prefer over typedef:

usingis always at least as readable astypedef, often much more so - Template aliases impossible with typedef: Critical advantage of modern using syntax

- class using for overloads: Restoring hidden overloads when overriding base class methods

- std:: always in headers: Defensive practice — headers are included widely, qualify everything

- Consistency: Pick a style for your codebase and enforce it — inconsistency causes confusion

Output:

=== Best Practices Summary ===

Names count: 3

Matrix[1][2] = 6

=== Rules to live by ===

1. NEVER using namespace in headers

2. PREFER using declarations over directives

3. PREFER using over typedef for type aliases

4. LIMIT using directives to function scope when needed

5. USE template aliases (using) for generic code

6. IN classes: use 'using Base::member' to manage overloads

7. QUALIFY std:: in all header files always

Processing: Alice

Processing: Bob

Processing: CharlieConclusion: using the Right using

The using keyword is one of C++’s most versatile tools, but that versatility demands discipline. Using the wrong form in the wrong place causes the exact name-collision problems that namespaces were designed to prevent.

Key takeaways:

- Two distinct mechanisms: The

usingdirective (imports a namespace) and theusingdeclaration (imports one name) have very different impacts - using directive:

using namespace std;imports everything—convenient for learning, dangerous in production - using declaration:

using std::cout;imports one name—explicit, safe, preferred for real code - NEVER in headers: Both the directive and declaration pollute every file that includes your header—this rule is non-negotiable

- Function scope is safest: Both forms used inside a function body are limited to that function

- Type aliases:

using T = long_type;is strictly better thantypedef—clearer syntax and supports templates - Template aliases:

template<typename T> using Vec = vector<T>;is impossible with typedef—a key advantage - Inheritance using:

using Base::memberrestores hidden overloads, changes accessibility, and inherits constructors - Scope and shadowing: Local declarations shadow using-introduced names—name lookup prefers inner scope

- The tutorial exception:

using namespace stdin examples and tutorials is a deliberate simplification—recognize it for what it is

Use using purposefully: type aliases generously, declarations selectively, directives sparingly, and never in headers.