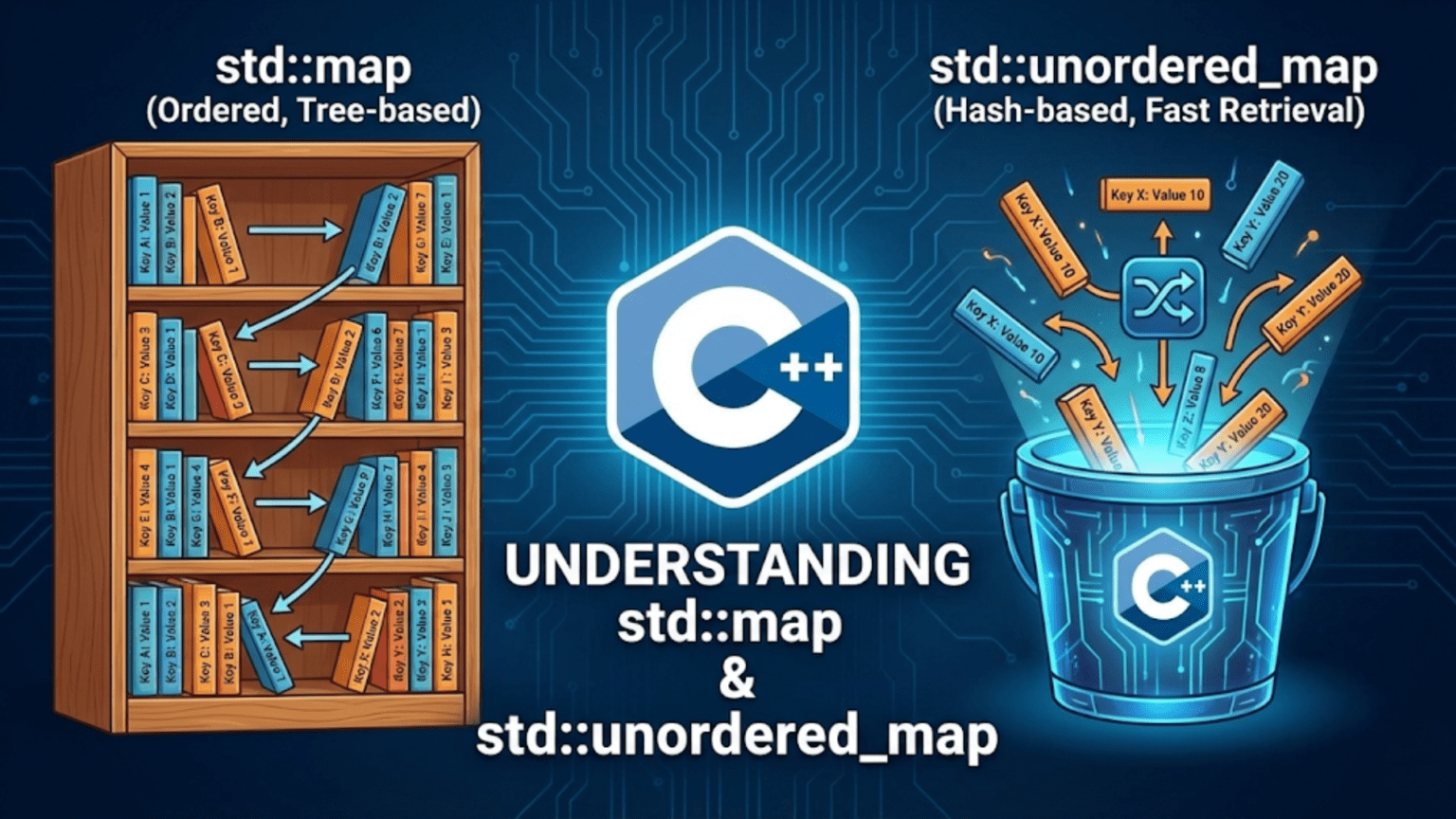

std::map and std::unordered_map are both C++ associative containers that store key-value pairs with unique keys. std::map keeps keys sorted in ascending order using a red-black tree, providing O(log n) operations and ordered iteration. std::unordered_map uses a hash table for O(1) average-case lookup and insertion, but provides no ordering. Choose map when you need sorted keys or range queries; choose unordered_map when you need maximum lookup speed.

Introduction: When You Need Key-Value Storage

Associative containers are among the most commonly used data structures in real-world programming. Whether you’re counting word frequencies, caching API results, building a phone book, storing configuration settings, or implementing a symbol table, you need a structure that maps keys to values and enables fast lookup by key. In C++, std::map and std::unordered_map are your primary tools for this purpose.

Both containers store key-value pairs where each key is unique. The fundamental difference lies in how they organize data internally: std::map uses a self-balancing binary search tree (red-black tree), which keeps keys sorted and guarantees O(log n) for all operations. std::unordered_map uses a hash table, which provides O(1) average-case performance for lookup, insertion, and deletion but has no concept of ordering.

This distinction has real consequences for how you use them. With std::map, you can iterate through keys in sorted order, find the nearest key to a given value, or query a range of keys. With std::unordered_map, you sacrifice those capabilities for raw speed—lookups are typically much faster, especially for large datasets.

This comprehensive guide will teach you everything about both containers: how they work internally, how to create, access, modify, and iterate them, how to handle common operations like counting and grouping, and exactly when to choose one over the other. Every concept is illustrated with practical, step-by-step examples.

std::map Fundamentals

std::map stores key-value pairs sorted by key. It is the right container when order matters or when you need to iterate keys in sequence.

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// --- Creating a map ---

cout << "=== Creating and inserting into map ===" << endl;

map<string, int> scores;

// Method 1: operator[]

scores["Alice"] = 92;

scores["Charlie"] = 85;

scores["Bob"] = 78;

scores["Diana"] = 95;

// Method 2: insert() with make_pair

scores.insert(make_pair("Eve", 88));

// Method 3: emplace() — constructs in-place

scores.emplace("Frank", 91);

// Method 4: insert with initializer

scores.insert({"Grace", 84});

// --- Iterating (always sorted by key) ---

cout << "Scores (sorted alphabetically):" << endl;

for (const auto& [name, score] : scores) {

cout << " " << name << ": " << score << endl;

}

// --- Size and empty check ---

cout << "\nTotal entries: " << scores.size() << endl;

cout << "Is empty? " << (scores.empty() ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- map<string, int>: Declares a map where keys are strings and values are integers

- operator[] for insertion:

scores["Alice"] = 92inserts key “Alice” with value 92 - Insertion order irrelevant: Charlie inserted before Bob, but map sorts them

- make_pair(): Helper that creates a std::pair — traditional insert syntax

- emplace(): Constructs the pair directly in the map — avoids temporary creation

- insert({“Grace”, 84}): Brace initialization of pair — cleanest modern syntax

- Structured binding [name, score]: C++17 syntax unpacks the pair automatically

- Always sorted output: Regardless of insertion order, map always iterates alphabetically

- Red-black tree internals: Keeps keys balanced — guarantees O(log n) operations

- size(): Returns number of key-value pairs currently stored

- empty(): Returns true if no entries — O(1), prefer over

size() == 0 - Unique keys enforced: Inserting “Alice” again would update, not duplicate

- const auto& pair: Reference to avoid copying — especially important for large value types

Output:

=== Creating and inserting into map ===

Scores (sorted alphabetically):

Alice: 92

Bob: 78

Charlie: 85

Diana: 95

Eve: 88

Frank: 91

Grace: 84

Total entries: 7

Is empty? NoAccessing and Looking Up Values

Map provides several ways to access values — understanding the difference between them prevents common bugs.

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

map<string, int> inventory = {

{"apples", 50},

{"bananas", 30},

{"cherries", 100}

};

// --- operator[]: access or INSERT if missing ---

cout << "=== operator[] ===" << endl;

cout << "Apples: " << inventory["apples"] << endl;

cout << "Bananas: " << inventory["bananas"] << endl;

// DANGER: operator[] creates a default entry if key doesn't exist!

cout << "Grapes (not in map): " << inventory["grapes"] << endl;

cout << "Map size after accessing 'grapes': " << inventory.size() << endl;

// "grapes" is now in the map with value 0!

// --- at(): access with bounds check (NO insertion) ---

cout << "\n=== at() ===" << endl;

cout << "Cherries: " << inventory.at("cherries") << endl;

try {

cout << "Oranges: " << inventory.at("oranges") << endl;

} catch (const out_of_range& e) {

cout << "Exception: key 'oranges' not found" << endl;

}

// --- find(): safe existence check ---

cout << "\n=== find() ===" << endl;

auto it = inventory.find("apples");

if (it != inventory.end()) {

cout << "Found apples: " << it->second << endl;

}

auto it2 = inventory.find("oranges");

if (it2 == inventory.end()) {

cout << "Oranges not found in map" << endl;

}

// --- count(): check existence (returns 0 or 1 for map) ---

cout << "\n=== count() ===" << endl;

cout << "Has 'bananas': " << (inventory.count("bananas") ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

cout << "Has 'oranges': " << (inventory.count("oranges") ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

// --- contains() (C++20) ---

// cout << "Has 'apples': " << inventory.contains("apples") << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Initializer list construction:

map<string,int>can be initialized with{ {key,val}, ... } - operator[] for read:

inventory["apples"]returns reference to the stored value - operator[] danger: If key doesn’t exist, it creates a new entry with default value (0 for int)

- Silent insertion: Accessing “grapes” adds it to the map — map size grows unexpectedly

- Size increases: After

inventory["grapes"], size goes from 3 to 4 - at() for safe read: Throws

std::out_of_rangeif key absent — never inserts - at() for critical code: Use at() whenever absent keys indicate a bug

- try-catch: Catches the exception thrown by at() for missing key

- find() returns iterator: Points to the key-value pair if found, or end() if not

- it->second: Arrow operator on iterator — accesses the value part of the pair

- it->first: Would give the key part (string)

- it == inventory.end(): Standard idiom to check “not found”

- count(): Returns 1 if key exists, 0 if not — safe existence check without insertion

- When to use each:

[]for insert-or-update,find()for safe lookup,at()for mandatory presence

Output:

=== operator[] ===

Apples: 50

Bananas: 30

Grapes (not in map): 0

Map size after accessing 'grapes': 4

=== at() ===

Cherries: 100

Exception: key 'oranges' not found

=== find() ===

Found apples: 50

Oranges not found in map

=== count() ===

Has 'bananas': Yes

Has 'oranges': NoModifying and Erasing Map Entries

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

map<string, int> stock = {

{"apple", 10}, {"banana", 5}, {"cherry", 20},

{"date", 8}, {"elderberry", 15}

};

// --- Updating values ---

cout << "=== Updating values ===" << endl;

stock["apple"] = 25; // Overwrite with operator[]

stock.at("banana") = 12; // Overwrite with at()

// insert_or_assign (C++17): updates if exists, inserts if not

stock.insert_or_assign("cherry", 30);

stock.insert_or_assign("fig", 7); // New entry

cout << "After updates:" << endl;

for (const auto& [k, v] : stock) cout << " " << k << ": " << v << endl;

// --- Erasing by key ---

cout << "\n=== Erasing by key ===" << endl;

stock.erase("date");

cout << "After erasing 'date', size: " << stock.size() << endl;

// Safe erase (check first)

string toErase = "mango";

if (stock.count(toErase)) {

stock.erase(toErase);

cout << "Erased " << toErase << endl;

} else {

cout << toErase << " not in map — nothing erased" << endl;

}

// --- Erasing by iterator ---

cout << "\n=== Erasing by iterator ===" << endl;

auto it = stock.find("elderberry");

if (it != stock.end()) {

cout << "Erasing: " << it->first << endl;

stock.erase(it);

}

// --- Erasing a range ---

cout << "\n=== Erasing a range ===" << endl;

auto first = stock.begin();

auto last = next(first, 2); // Iterator to 3rd element

stock.erase(first, last); // Erase first two elements

cout << "After range erase:" << endl;

for (const auto& [k, v] : stock) cout << " " << k << ": " << v << endl;

// --- clear ---

stock.clear();

cout << "\nAfter clear, size: " << stock.size() << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- operator[] update:

stock["apple"] = 25overwrites the existing value for “apple” - at() update:

stock.at("banana") = 12— safer update (throws if key missing) - insert_or_assign (C++17): Inserts if key absent, assigns if key present — explicit intent

- New key with insert_or_assign: “fig” is inserted because it doesn’t exist yet

- erase(key): Removes entry by key — O(log n), returns number of elements removed (0 or 1)

- Safe erase pattern: count() before erase avoids erasing from wrong map

- erase returns 0 or 1: For map (unique keys), returns 0 if not found, 1 if erased

- erase by iterator: O(1) — more efficient when you already have the iterator from find()

- it != stock.end(): Always verify iterator is valid before using it

- it->first: Accesses the key — printed before erasing

- std::next(first, 2): Advances iterator by 2 steps without modifying it

- Range erase: Removes [first, last) — half-open interval, last element is NOT removed

- sorted deletion: Map is sorted, so first two elements are alphabetically first

- clear(): Removes all entries — size becomes 0, capacity freed

Output:

=== Updating values ===

After updates:

apple: 25

banana: 12

cherry: 30

date: 8

elderberry: 15

fig: 7

=== Erasing by key ===

After erasing 'date', size: 5

mango not in map — nothing erased

=== Erasing by iterator ===

Erasing: elderberry

=== Erasing a range ===

After range erase:

cherry: 30

fig: 7

After clear, size: 0Map Iteration and Ordering Features

The sorted nature of std::map enables powerful ordered operations unavailable in unordered_map.

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

map<int, string> events = {

{2023, "Product Launch"},

{2019, "Company Founded"},

{2021, "Series A Funding"},

{2025, "IPO"},

{2020, "First Customer"}

};

// --- Forward iteration (ascending key order) ---

cout << "=== Chronological order ===" << endl;

for (const auto& [year, event] : events) {

cout << " " << year << ": " << event << endl;

}

// --- Reverse iteration (descending key order) ---

cout << "\n=== Reverse chronological ===" << endl;

for (auto it = events.rbegin(); it != events.rend(); ++it) {

cout << " " << it->first << ": " << it->second << endl;

}

// --- lower_bound: first key >= given key ---

cout << "\n=== lower_bound(2021) ===" << endl;

auto lb = events.lower_bound(2021);

cout << "First event in 2021 or later: "

<< lb->first << " - " << lb->second << endl;

// --- upper_bound: first key > given key ---

cout << "\n=== upper_bound(2021) ===" << endl;

auto ub = events.upper_bound(2021);

cout << "First event after 2021: "

<< ub->first << " - " << ub->second << endl;

// --- Range query: events between 2020 and 2023 (inclusive) ---

cout << "\n=== Range query: 2020 to 2023 ===" << endl;

auto rangeStart = events.lower_bound(2020);

auto rangeEnd = events.upper_bound(2023);

for (auto it = rangeStart; it != rangeEnd; ++it) {

cout << " " << it->first << ": " << it->second << endl;

}

// --- equal_range: both bounds at once ---

cout << "\n=== equal_range(2021) ===" << endl;

auto [lo, hi] = events.equal_range(2021);

for (auto it = lo; it != hi; ++it) {

cout << " Exact match: " << it->first << " - " << it->second << endl;

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Map sorted by int key: Events stored in arbitrary order but always iterated by year

- Automatic ordering: 2019 → 2020 → 2021 → 2023 → 2025 regardless of insertion order

- rbegin() / rend(): Reverse iterators traverse the sorted tree from largest to smallest key

- Reverse chronological: Useful for showing most recent first

- lower_bound(2021): Returns iterator to first key ≥ 2021 — includes 2021 itself

- O(log n) for lower_bound: Uses tree structure for binary search

- upper_bound(2021): Returns iterator to first key > 2021 — excludes 2021 itself

- Range query pattern:

lower_bound(start)toupper_bound(end)creates an inclusive range - Half-open range:

[rangeStart, rangeEnd)— rangeEnd points past the last included element - 2020–2023 range: Captures exactly the events in those years

- equal_range(): Returns pair of {lower_bound, upper_bound} — useful for multimap

- Structured binding on pair:

auto [lo, hi] = equal_range(2021)unpacks cleanly - Single-element range: For map (unique keys), lo == hi – 1 for existing key

- These features absent in unordered_map: Hash tables have no ordering — no range queries

Output:

=== Chronological order ===

2019: Company Founded

2020: First Customer

2021: Series A Funding

2023: Product Launch

2025: IPO

=== Reverse chronological ===

2025: IPO

2023: Product Launch

2021: Series A Funding

2020: First Customer

2019: Company Founded

=== lower_bound(2021) ===

First event in 2021 or later: 2021 - Series A Funding

=== upper_bound(2021) ===

First event after 2021: 2023 - Product Launch

=== Range query: 2020 to 2023 ===

2020: First Customer

2021: Series A Funding

2023: Product Launch

=== equal_range(2021) ===

Exact match: 2021 - Series A Fundingstd::unordered_map Fundamentals

std::unordered_map trades ordering for speed. Its hash-table implementation delivers O(1) average-case performance for all primary operations.

#include <iostream>

#include <unordered_map>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// --- Creating unordered_map ---

cout << "=== Creating unordered_map ===" << endl;

unordered_map<string, int> wordCount;

// Same insertion methods as map

wordCount["apple"] = 3;

wordCount["banana"] = 1;

wordCount["cherry"] = 5;

wordCount.insert({"date", 2});

wordCount.emplace("elderberry", 4);

cout << "Entries (order NOT guaranteed):" << endl;

for (const auto& [word, count] : wordCount) {

cout << " " << word << ": " << count << endl;

}

// --- Lookup is O(1) average ---

cout << "\n=== O(1) Lookups ===" << endl;

cout << "apple count: " << wordCount["apple"] << endl;

cout << "cherry count: " << wordCount.at("cherry") << endl;

// --- Hash table internals ---

cout << "\n=== Hash Table Info ===" << endl;

cout << "Bucket count: " << wordCount.bucket_count() << endl;

cout << "Load factor: " << wordCount.load_factor() << endl;

cout << "Max load factor: " << wordCount.max_load_factor() << endl;

cout << "Bucket for 'apple': " << wordCount.bucket("apple") << endl;

// --- reserve: optimize bucket count upfront ---

unordered_map<string, int> large;

large.reserve(1000); // Pre-allocate for ~1000 elements

cout << "\nAfter reserve(1000) — bucket_count: "

<< large.bucket_count() << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- unordered_map<string, int>: Template parameters identical to map — key, value

- Same insertion API: operator[], insert(), emplace() — consistent interface

- Order not guaranteed: Output order depends on hash function — changes between runs

- O(1) average lookup: Hash function maps key to bucket index directly

- bucket_count(): Number of hash buckets — always >= size() to limit collisions

- load_factor(): size / bucket_count — low load factor means fewer collisions

- max_load_factor(): Default is 1.0 — when load_factor exceeds this, rehashing occurs

- Rehashing: Triggered automatically — similar to vector’s reallocation — amortized O(1)

- bucket(“apple”): Shows which bucket index the key “apple” hashes to

- reserve(1000): Pre-allocates enough buckets to hold 1000 elements without rehashing

- When to reserve: Avoids expensive rehashing when final size is known in advance

- Predictability: After reserve, inserts won’t trigger rehashing up to reserved size

- O(1) worst case isn’t guaranteed: Hash collisions can degrade to O(n) — rare in practice

- Same API as map: Learning one teaches you the other — only ordering behavior differs

Output:

=== Creating unordered_map ===

Entries (order NOT guaranteed):

elderberry: 4

date: 2

cherry: 5

banana: 1

apple: 3

=== O(1) Lookups ===

apple count: 3

cherry count: 5

=== Hash Table Info ===

Bucket count: 11

Load factor: 0.454545

Max load factor: 1

Bucket for 'apple': 7

After reserve(1000) — bucket_count: 1024Word Frequency Counter: Classic Map Use Case

Counting frequencies is the most common real-world use of maps. Here’s how both containers handle it.

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <unordered_map>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<string> words = {

"the", "quick", "brown", "fox", "jumps", "over",

"the", "lazy", "dog", "the", "fox", "quick"

};

// --- Counting with map (sorted output) ---

cout << "=== Word Frequency with map ===" << endl;

map<string, int> mapFreq;

for (const string& word : words) {

mapFreq[word]++; // Creates 0 if absent, then increments

}

cout << "Frequencies (alphabetical):" << endl;

for (const auto& [word, count] : mapFreq) {

cout << " " << word << ": " << count << endl;

}

// Find most frequent word in map

auto maxIt = max_element(mapFreq.begin(), mapFreq.end(),

[](const auto& a, const auto& b) { return a.second < b.second; });

cout << "Most frequent: '" << maxIt->first

<< "' (" << maxIt->second << " times)" << endl;

// --- Counting with unordered_map (faster) ---

cout << "\n=== Word Frequency with unordered_map ===" << endl;

unordered_map<string, int> umapFreq;

for (const string& word : words) {

umapFreq[word]++;

}

// Sort by frequency (copy to vector since unordered_map can't sort)

vector<pair<string, int>> sorted(umapFreq.begin(), umapFreq.end());

sort(sorted.begin(), sorted.end(),

[](const auto& a, const auto& b) { return a.second > b.second; });

cout << "Frequencies (sorted by count, descending):" << endl;

for (const auto& [word, count] : sorted) {

cout << " " << word << ": " << count << endl;

}

// --- Words appearing exactly once ---

cout << "\n=== Words appearing exactly once ===" << endl;

for (const auto& [word, count] : mapFreq) {

if (count == 1) cout << " " << word << endl;

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- mapFreq[word]++: If “the” not in map, creates entry with value 0, then ++ makes it 1

- Subsequent encounters: Second “the” — key exists, value incremented to 2

- Self-inserting pattern: operator[] combined with ++ is the canonical counting idiom

- Alphabetical output: map iterates in sorted key order automatically

- max_element(): STL algorithm finding iterator to maximum element using comparator

- Lambda comparator:

a.second < b.secondcompares by value (count), not key - maxIt->first and ->second: Access key and value through the iterator

- unordered_map for speed: Same counting logic, but O(1) average per lookup vs O(log n)

- Can’t sort unordered_map directly: It’s a hash table — no ordering concept

- Copy to vector of pairs:

vector<pair<string,int>>(umapFreq.begin(), umapFreq.end()) - Sort the vector: vector supports arbitrary sorting — sort by count descending

- Lambda for descending:

a.second > b.second— largest count first - Filtering by count: After counting, range-for with condition finds singleton words

- map preferred for filtering: Sorted order makes filtering and range queries natural

Output:

=== Word Frequency with map ===

Frequencies (alphabetical):

brown: 1

dog: 1

fox: 2

jumps: 1

lazy: 1

over: 1

quick: 2

the: 3

Most frequent: 'the' (3 times)

=== Word Frequency with unordered_map ===

Frequencies (sorted by count, descending):

the: 3

quick: 2

fox: 2

brown: 1

jumps: 1

lazy: 1

over: 1

dog: 1

=== Words appearing exactly once ===

brown

dog

jumps

lazy

overCustom Key Types

By default, map uses operator< for ordering and unordered_map uses std::hash<Key>. For custom types, you need to provide these.

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <unordered_map>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

// Custom key type for map

struct Point {

int x, y;

// Required for std::map: defines ordering

bool operator<(const Point& other) const {

if (x != other.x) return x < other.x;

return y < other.y; // Tie-break by y

}

bool operator==(const Point& other) const {

return x == other.x && y == other.y;

}

};

// Custom hash for unordered_map

struct PointHash {

size_t operator()(const Point& p) const {

// Combine hashes of x and y

size_t hx = hash<int>()(p.x);

size_t hy = hash<int>()(p.y);

return hx ^ (hy << 32); // XOR-shift combination

}

};

int main() {

// --- map with custom key (uses operator<) ---

cout << "=== map with custom Point key ===" << endl;

map<Point, string> grid;

grid[{0, 0}] = "Origin";

grid[{1, 0}] = "East";

grid[{0, 1}] = "North";

grid[{-1, 0}] = "West";

cout << "Points (sorted by x then y):" << endl;

for (const auto& [pt, label] : grid) {

cout << " (" << pt.x << "," << pt.y << ") -> " << label << endl;

}

// --- unordered_map with custom key and hash ---

cout << "\n=== unordered_map with custom Point key ===" << endl;

unordered_map<Point, string, PointHash> hashGrid;

hashGrid[{0, 0}] = "Origin";

hashGrid[{1, 0}] = "East";

hashGrid[{0, 1}] = "North";

Point lookup = {1, 0};

auto it = hashGrid.find(lookup);

if (it != hashGrid.end()) {

cout << "Found (" << lookup.x << "," << lookup.y

<< ") -> " << it->second << endl;

}

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Custom Point struct: Has x and y integer coordinates

- operator< for map: Required by std::map to maintain sorted order

- Lexicographic comparison: Sort by x first; if x equals, sort by y

- operator== for unordered_map: Required to handle hash collisions

- PointHash struct: Functor providing hash function for Point

- size_t return: Hash must return size_t (unsigned integer type)

- hash<int>()(p.x): Calls standard hash for int on p.x

- XOR-shift combination: Common technique to combine two hashes

- Good hash spreads values: Minimizes collisions by distributing buckets evenly

- map uses operator<: Internally compares keys with < to maintain tree order

- unordered_map<Point, string, PointHash>: Third template param is the hash type

- {0, 0} aggregate init: Brace-initializes Point struct

- map sorts by Point ordering: (-1,0) < (0,0) < (0,1) < (1,0)

- find() with Point: Hashes the lookup Point and checks equality of found entry

Output:

=== map with custom Point key ===

Points (sorted by x then y):

(-1,0) -> West

(0,0) -> Origin

(0,1) -> North

(1,0) -> East

=== unordered_map with custom Point key ===-

Found (1,0) -> Eastmap vs unordered_map: Head-to-Head Comparison

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <unordered_map>

#include <chrono>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

const int N = 100000;

// --- Insert performance ---

cout << "=== Insert " << N << " elements ===" << endl;

auto start = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

map<int, int> m;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) m[i] = i * i;

auto end = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto mapInsertTime = chrono::duration_cast<chrono::microseconds>(end - start).count();

cout << "map insert time: " << mapInsertTime << " μs" << endl;

start = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

unordered_map<int, int> um;

um.reserve(N);

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) um[i] = i * i;

end = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto umInsertTime = chrono::duration_cast<chrono::microseconds>(end - start).count();

cout << "unordered_map insert time: " << umInsertTime << " μs" << endl;

// --- Lookup performance ---

cout << "\n=== Lookup " << N << " elements ===" << endl;

start = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

long long mapSum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) mapSum += m.at(i);

end = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto mapLookupTime = chrono::duration_cast<chrono::microseconds>(end - start).count();

cout << "map lookup time: " << mapLookupTime << " μs" << endl;

start = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

long long umSum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) umSum += um.at(i);

end = chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto umLookupTime = chrono::duration_cast<chrono::microseconds>(end - start).count();

cout << "unordered_map lookup time: " << umLookupTime << " μs" << endl;

cout << "\nResults match: " << (mapSum == umSum ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- chrono::high_resolution_clock: C++ standard library timer — nanosecond precision

- chrono::duration_cast<microseconds>: Converts elapsed time to microseconds

- N = 100000: Large dataset reveals real performance differences

- map insert O(log n): Each insertion traverses and rebalances the red-black tree

- unordered_map reserve(): Pre-allocates buckets, avoiding rehashing during insertions

- unordered_map insert O(1) avg: Direct hash computation, no tree traversal

- at() for lookup: Safe access used in both — same logical operation, different internals

- mapSum and umSum: Summing all values verifies both containers hold same data

- Results match: Both containers store same values — only organization differs

- Performance difference: unordered_map typically 2-5x faster for large N

- map constant overhead: Tree traversal adds per-operation overhead even for small N

- unordered_map variance: Hash collision handling can cause occasional slowdowns

- Benchmark lesson: Always measure — don’t assume one is faster for your specific data

- real-world factors: Cache behavior, key type complexity, load factor all affect results

Output (values vary by machine):

=== Insert 100000 elements ===

map insert time: 48230 μs

unordered_map insert time: 18410 μs

=== Lookup 100000 elements ===

map lookup time: 31540 μs

unordered_map lookup time: 9870 μs

Results match: YesComparison Table

| Feature | std::map | std::unordered_map |

|---|---|---|

| Internal structure | Red-black tree | Hash table |

| Key ordering | Always sorted (ascending) | No ordering |

| Lookup | O(log n) | O(1) average |

| Insert | O(log n) | O(1) average |

| Delete | O(log n) | O(1) average |

| Iteration order | Sorted by key | Arbitrary |

| Range queries | Yes (lower/upper_bound) | No |

| Memory usage | Higher (node pointers) | Lower (contiguous buckets) |

| Key requirement | operator< | hash + operator== |

| Worst-case lookup | O(log n) guaranteed | O(n) on hash collision |

| Use when | Need sorted keys, ranges | Need maximum speed |

| STL equivalent | TreeMap (Java) | HashMap (Java) |

When to Choose Which

// Use std::map when:

// 1. You need keys in sorted order

map<string, int> sortedConfig; // Config values printed alphabetically

// 2. You need range queries

map<int, Event> timeline; // Find all events between year A and B

// 3. You need ordered iteration

map<double, string> pricedItems; // Iterate from cheapest to most expensive

// 4. Keys are hard to hash (custom types without hash function)

map<ComplexType, Value> m; // Only needs operator<

// Use std::unordered_map when:

// 1. You need maximum lookup speed

unordered_map<string, CachedResult> cache; // Fast cache lookup

// 2. Order doesn't matter

unordered_map<string, int> wordFreq; // Just need counts

// 3. Large datasets where O(log n) vs O(1) matters

unordered_map<UserID, Profile> users; // Millions of users, frequent lookups

// 4. You have a good hash function for your key type

unordered_map<string, Data> db; // string already has std::hashConclusion: Choosing the Right Map for the Job

Both std::map and std::unordered_map are indispensable tools in the C++ programmer’s toolkit, solving the same fundamental problem—key-value association—through fundamentally different mechanisms. Understanding those mechanisms is what allows you to choose the right tool for each situation.

Key takeaways:

- std::map uses a red-black tree: always sorted, O(log n) guaranteed, supports range queries and ordered iteration

- std::unordered_map uses a hash table: O(1) average performance, no ordering, faster for pure lookup workloads

- The

operator[]creates entries if the key is missing — usefind()orcount()for safe existence checks at()provides bounds-checked access that throwsout_of_range— use during development or when absence is a bug- Custom key types require

operator<for map andhash + operator==for unordered_map insert_or_assign()(C++17) explicitly communicates “insert or update” intentlower_bound()andupper_bound()on map enable powerful range queries — unavailable on unordered_map- Reserve capacity with

reserve()on unordered_map to avoid rehashing overhead - When in doubt about performance, benchmark — actual gains depend on key type, dataset size, and access pattern

Master both containers, understand their trade-offs, and you’ll handle key-value problems in C++ with confidence and efficiency.