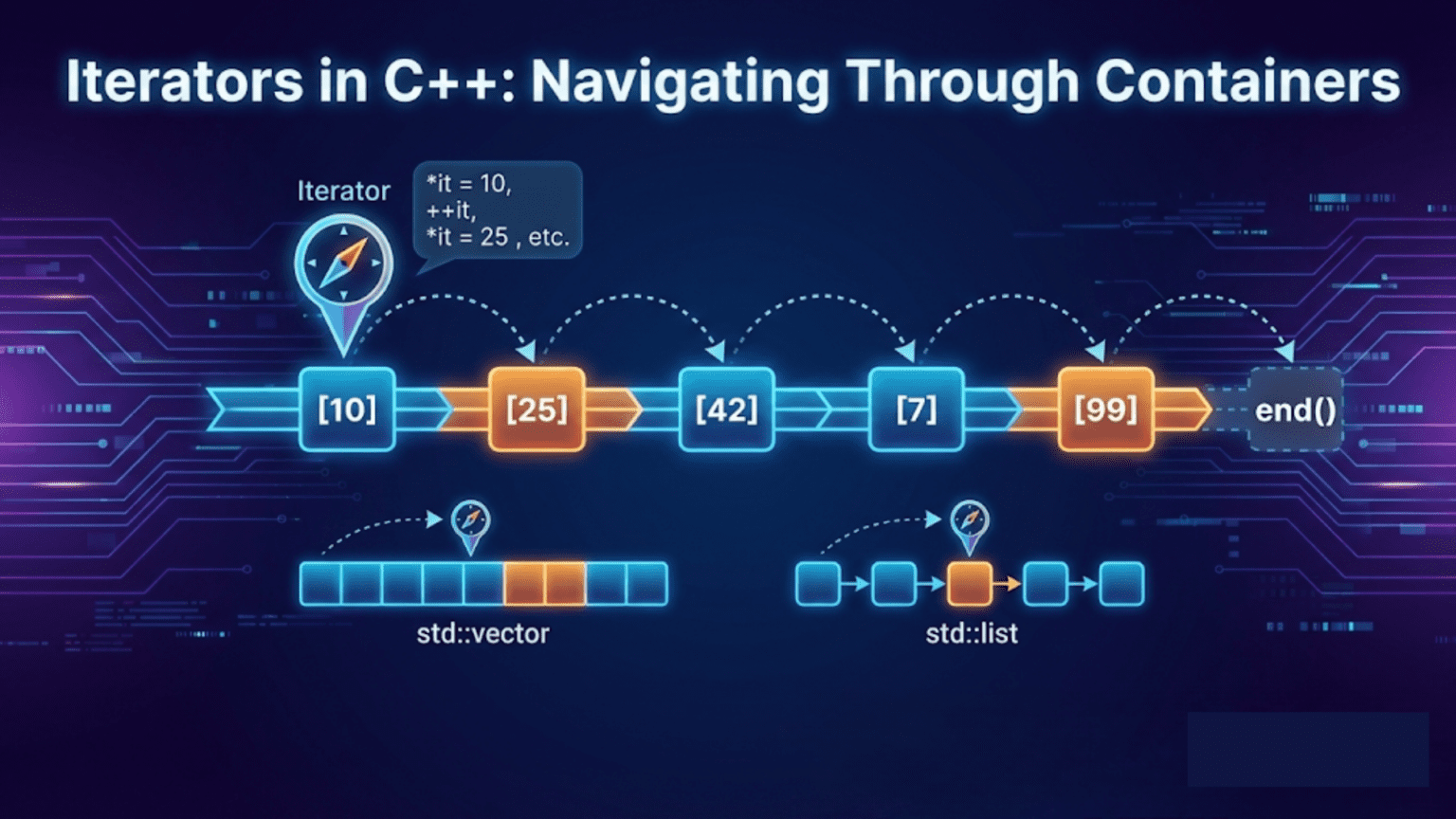

Iterators in C++ are pointer-like objects that provide a uniform interface for traversing and accessing elements in any container, from vectors to lists to maps. The STL defines five iterator categories—input, output, forward, bidirectional, and random-access—each supporting a specific set of operations. By abstracting element access through iterators, C++ algorithms become completely independent of container types, enabling the same sort() or find() to work on any compatible data structure.

Introduction: The Universal Language of Containers

Imagine you have five different filing systems—a folder stack, a Rolodex, a spreadsheet, a binder, and a card box. Each stores information differently, but you can interact with all of them through a common interface: open to a page, read it, move to the next page. That’s what iterators do for C++ containers.

Iterators are the glue that holds the STL together. Without them, every container would need its own version of every algorithm, and every algorithm would need to know about every container. With iterators, the relationship is clean: containers provide iterators, algorithms operate through iterators, and neither needs to know anything about the other’s internals.

When you write for (int n : v) or call sort(v.begin(), v.end()), you’re using iterators. The range-based for loop is just syntactic sugar for iterator traversal. Every STL algorithm that takes a begin and end parameter is working through iterators. Even raw C pointers are valid iterators—which is why STL algorithms work on plain arrays as well as containers.

This guide demystifies iterators completely. You’ll learn what they are, how the five iterator categories differ, what operations each supports, how begin/end and reverse/const iterators work, how iterator adaptors extend their utility, and how to write your own iterator for a custom container. Every concept is grounded in practical, step-by-step examples.

Iterator Basics: Pointers That Know Their Container

An iterator behaves like a pointer: you dereference it to get the value, increment it to move forward, and compare it to another iterator to check position.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <list>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

// --- Manual iterator usage ---

cout << "=== Manual iterator traversal ===" << endl;

vector<int>::iterator it = v.begin(); // Points to first element

cout << "First element: " << *it << endl; // Dereference: get value

++it; // Advance to next element

cout << "Second element: " << *it << endl;

it += 2; // Jump ahead 2 (random-access only)

cout << "Fourth element: " << *it << endl;

--it; // Go back one

cout << "Third element: " << *it << endl;

// --- auto keyword simplifies type ---

cout << "\n=== auto simplifies iterator type ===" << endl;

auto it2 = v.begin();

while (it2 != v.end()) {

cout << *it2 << " ";

++it2;

}

cout << endl;

// --- Iterator arithmetic ---

cout << "\n=== Iterator arithmetic ===" << endl;

auto first = v.begin();

auto last = v.end();

cout << "Distance (size): " << distance(first, last) << endl;

cout << "Third element via arithmetic: " << *(first + 2) << endl;

cout << "Last element: " << *(last - 1) << endl;

// --- Comparing iterators ---

cout << "\n=== Comparing iterators ===" << endl;

auto a = v.begin();

auto b = v.begin() + 3;

cout << "a < b: " << (a < b ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

cout << "a == b: " << (a == b ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

// --- Iterators on different container types ---

cout << "\n=== Iterators work the same on list ===" << endl;

list<string> words = {"apple", "banana", "cherry"};

for (auto it3 = words.begin(); it3 != words.end(); ++it3) {

cout << *it3 << " ";

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- vector<int>::iterator: Full type name of a vector’s iterator — verbose but explicit

- v.begin(): Returns iterator pointing to the first element (index 0)

- *it: Dereference operator — retrieves the value at the current iterator position

- ++it: Pre-increment — advances iterator to point to the next element

- it += 2: Jump by 2 positions — only works for random-access iterators (like vector’s)

- –it: Go back one position — bidirectional and random-access iterators support this

- auto it2 = v.begin(): Type deduction — compiler infers vector<int>::iterator automatically

- it2 != v.end(): Loop condition — v.end() is one-past-last, so stop when you reach it

- distance(first, last): Counts steps from first to last — O(1) for random-access, O(n) for others

- first + 2: Pointer-like arithmetic — jumps directly to the element 2 positions ahead

- last – 1: Points to the actual last element (end() itself is past the last)

- a < b: Relational comparison — valid for random-access iterators, not all iterators

- a == b: Equality comparison — valid for all iterator categories

- Same interface for list: list has different internals but same begin()/end()/++/*/!= interface

Output:

=== Manual iterator traversal ===

First element: 10

Second element: 20

Fourth element: 40

Third element: 30

=== auto simplifies iterator type ===

10 20 30 40 50

=== Iterator arithmetic ===

Distance (size): 5

Third element via arithmetic: 30

Last element: 50

=== Comparing iterators ===

a < b: Yes

a == b: No

=== Iterators work the same on list ===

apple banana cherryThe Five Iterator Categories

C++ defines five iterator categories in a hierarchy, each adding capabilities to the one below it.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <list>

#include <forward_list>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// ─── CATEGORY 1: Input Iterator ─────────────────────────────────

// Supports: read, ++, !=, ==

// Cannot: write, go back, random access

// Typical use: istream_iterator (reading from stream)

cout << "=== Input Iterator (istream_iterator) ===" << endl;

// istream_iterator<int> reads integers from input stream

// (shown conceptually — actual use reads from cin)

// istream_iterator<int> begin(cin), end;

// copy(begin, end, back_inserter(v));

cout << " Read-only, single-pass traversal (e.g., reading from file)" << endl;

// ─── CATEGORY 2: Output Iterator ────────────────────────────────

// Supports: write, ++

// Cannot: read, go back, compare

// Typical use: ostream_iterator, back_inserter

cout << "\n=== Output Iterator (ostream_iterator) ===" << endl;

vector<int> nums = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

ostream_iterator<int> outIt(cout, " ");

copy(nums.begin(), nums.end(), outIt);

cout << endl;

cout << " Write-only, single-pass (e.g., writing to stream)" << endl;

// ─── CATEGORY 3: Forward Iterator ───────────────────────────────

// Supports: read, write, ++, ==, !=

// Cannot: go back (--, --), random jump (+n)

// Typical: forward_list<T>::iterator

cout << "\n=== Forward Iterator (forward_list) ===" << endl;

forward_list<int> fwd = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

auto fwdIt = fwd.begin();

cout << "First: " << *fwdIt << endl;

++fwdIt;

cout << "Second: " << *fwdIt << endl;

++fwdIt;

cout << "Third: " << *fwdIt << endl;

// --fwdIt; // ERROR: forward_list iterator doesn't support going back

cout << " Forward only: supports ++ but NOT --" << endl;

// ─── CATEGORY 4: Bidirectional Iterator ─────────────────────────

// Supports: read, write, ++, --, ==, !=

// Cannot: random jump (+n, -n, [n])

// Typical: list<T>::iterator, map<K,V>::iterator

cout << "\n=== Bidirectional Iterator (list) ===" << endl;

list<int> lst = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

auto lstIt = lst.end();

--lstIt; // Move to last element

cout << "Last: " << *lstIt << endl;

--lstIt;

cout << "Second-last: " << *lstIt << endl;

++lstIt;

cout << "Last again: " << *lstIt << endl;

// lstIt + 3; // ERROR: list iterator doesn't support + arithmetic

cout << " Both ++ and -- work, but no +n or [n]" << endl;

// ─── CATEGORY 5: Random-Access Iterator ─────────────────────────

// Supports: ALL iterator operations

// read, write, ++, --, +n, -n, [n], <, >, <=, >=

// Typical: vector<T>::iterator, deque<T>::iterator, T*

cout << "\n=== Random-Access Iterator (vector) ===" << endl;

vector<int> vec = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

auto vecIt = vec.begin();

cout << "vecIt[0]: " << vecIt[0] << endl; // Subscript

cout << "vecIt[3]: " << vecIt[3] << endl; // Random jump

vecIt += 2;

cout << "After += 2: " << *vecIt << endl;

vecIt -= 1;

cout << "After -= 1: " << *vecIt << endl;

cout << "vecIt < vec.end(): " << (vecIt < vec.end() ? "Yes" : "No") << endl;

cout << " Full suite: ++, --, +n, -n, [n], <, >, <=, >=" << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- Input Iterator: Most restrictive — can only read and advance forward once (single-pass)

- istream_iterator: Classic input iterator — reads from stream, can’t go back

- Output Iterator: Write-only, single-pass — can write and advance but not read or compare

- ostream_iterator<int>(cout, ” “): Writes each element to cout with space separator

- copy() with output iterator: Uses output iterator to write elements from range

- Forward Iterator: Can read and write, advance forward multiple times (multi-pass)

- forward_list: Singly-linked list — supports ++ but NOT — (no backward pointers)

- Multi-pass: Can traverse the range multiple times unlike input/output iterators

- Bidirectional Iterator: Adds — (go backward) to forward iterator capabilities

- list iterator: Doubly-linked list — each node has prev/next pointers enabling —

- No random access: list doesn’t support

it + 3— must traverse node by node - Random-Access Iterator: Most powerful — adds arithmetic (+n, -n), subscript ([n]), relational (<, >)

- vector iterator: Backed by contiguous array — pointer arithmetic is direct and O(1)

- iterator[n]: Subscript operator is sugar for

*(it + n) - Hierarchy: Each category extends the one above it — random-access can do everything

Output:

=== Input Iterator (istream_iterator) ===

Read-only, single-pass traversal (e.g., reading from file)

=== Output Iterator (ostream_iterator) ===

1 2 3 4 5

Write-only, single-pass (e.g., writing to stream)

=== Forward Iterator (forward_list) ===

First: 10

Second: 20

Third: 30

Forward only: supports ++ but NOT --

=== Bidirectional Iterator (list) ===

Last: 50

Second-last: 40

Last again: 50

Both ++ and -- work, but no +n or [n]

=== Random-Access Iterator (vector) ===

vecIt[0]: 10

vecIt[3]: 40

After += 2: 30

After -= 1: 20

vecIt < vec.end(): Yes

Full suite: ++, --, +n, -n, [n], <, >, <=, >=begin(), end() and Their Variants

Each container provides multiple begin/end pairs for different traversal needs.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

// --- Standard begin/end ---

cout << "=== begin() and end() ===" << endl;

for (auto it = v.begin(); it != v.end(); ++it) {

cout << *it << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// --- Reverse iterators: rbegin/rend ---

cout << "\n=== rbegin() and rend() (reverse) ===" << endl;

for (auto rit = v.rbegin(); rit != v.rend(); ++rit) {

cout << *rit << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// Reverse iterator increments go backward

auto rit = v.rbegin();

cout << "rbegin dereferences to: " << *rit << " (last element)" << endl;

++rit; // moves BACKWARD in the container

cout << "After ++rit: " << *rit << " (second-to-last)" << endl;

// --- Const iterators: cbegin/cend ---

cout << "\n=== cbegin() and cend() (read-only) ===" << endl;

for (auto cit = v.cbegin(); cit != v.cend(); ++cit) {

cout << *cit << " ";

// *cit = 99; // ERROR: cannot assign through const_iterator

}

cout << endl;

// const_iterator vs const vector

const vector<int> cv = {1, 2, 3};

auto it = cv.begin(); // begin() on const vector returns const_iterator automatically

cout << "Const vector element: " << *it << endl;

// --- Const reverse iterators: crbegin/crend ---

cout << "\n=== crbegin() and crend() (const + reverse) ===" << endl;

for (auto crit = v.crbegin(); crit != v.crend(); ++crit) {

cout << *crit << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// --- Free function versions: std::begin, std::end ---

cout << "\n=== std::begin() and std::end() (free functions) ===" << endl;

int arr[] = {100, 200, 300, 400, 500};

// Works on arrays too — unlike member .begin()

for (auto it2 = begin(arr); it2 != end(arr); ++it2) {

cout << *it2 << " ";

}

cout << endl;

// Works on containers identically

for (auto it3 = begin(v); it3 != end(v); ++it3) {

cout << *it3 << " ";

}

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- v.begin(): Returns iterator to first element — type is vector<int>::iterator

- v.end(): Returns iterator one-past-last — never dereference this

- it != v.end(): Standard loop condition — checks we haven’t gone past the last element

- v.rbegin(): Reverse begin — points to the LAST element, moves backward with ++

- v.rend(): Reverse end — points one-before-first, the sentinel for reverse traversal

- ++ on reverse iterator: Paradoxically moves BACKWARD in the container (toward front)

- Reverse traversal output: 50, 40, 30, 20, 10 — container traversed from back to front

- v.cbegin() / v.cend(): Returns const_iterator — dereference gives const reference (read-only)

- *cit = 99 is compile error: const_iterator prevents modification — enforced by type system

- const vector calls const begin(): Member begin() is overloaded — const object calls const version

- v.crbegin() / v.crend(): Combines const + reverse — read-only backward traversal

- std::begin(arr): Free function version — works on plain C arrays (no .begin() member)

- std::end(arr): Computes end pointer for array using sizeof

- Template-friendly: Generic code prefers std::begin(x) over x.begin() — works for both arrays and containers

Output:

=== begin() and end() ===

10 20 30 40 50

=== rbegin() and rend() (reverse) ===

50 40 30 20 10

rbegin dereferences to: 50 (last element)

After ++rit: 40 (second-to-last)

=== cbegin() and cend() (read-only) ===

10 20 30 40 50

Const vector element: 1

=== crbegin() and crend() (const + reverse) ===

50 40 30 20 10

=== std::begin() and std::end() (free functions) ===

100 200 300 400 500

10 20 30 40 50Iterator Adaptors: Extending Iterator Capability

The STL provides iterator adaptors that wrap existing iterators or provide special-purpose iterator behavior.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <list>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iterator>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// --- back_inserter: appends to container ---

cout << "=== back_inserter ===" << endl;

vector<int> src = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

vector<int> dst;

// Without back_inserter: dst must be pre-sized

// copy(src.begin(), src.end(), dst.begin()); // CRASH - dst is empty

// With back_inserter: grows dst automatically

copy(src.begin(), src.end(), back_inserter(dst));

cout << "Copied to empty vector: ";

for (int n : dst) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// Filter and copy into empty vector

vector<int> evens;

copy_if(src.begin(), src.end(), back_inserter(evens),

[](int n){ return n % 2 == 0; });

cout << "Filtered evens: ";

for (int n : evens) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- front_inserter: prepends to container ---

cout << "\n=== front_inserter ===" << endl;

list<int> lst;

// front_inserter reverses the order (each element goes to front)

for (int n : {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}) {

front_inserter(lst) = n; // Inserts n at front

}

cout << "front_inserter result (reversed): ";

for (int n : lst) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

list<int> lst2;

copy(src.begin(), src.end(), front_inserter(lst2));

cout << "copy with front_inserter (reversed): ";

for (int n : lst2) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- inserter: inserts at a specific position ---

cout << "\n=== inserter ===" << endl;

vector<int> target = {10, 20, 30};

auto insertPos = target.begin() + 1; // Insert after first element

copy(src.begin(), src.end(), inserter(target, insertPos));

cout << "After inserting src at position 1: ";

for (int n : target) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- ostream_iterator: writes to output stream ---

cout << "\n=== ostream_iterator ===" << endl;

vector<string> words = {"Hello", "World", "from", "C++"};

copy(words.begin(), words.end(), ostream_iterator<string>(cout, " "));

cout << endl;

// Print integers with comma separator

vector<int> nums = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

ostream_iterator<int> commaIt(cout, ", ");

copy(nums.begin(), nums.end(), commaIt);

cout << endl;

// --- istream_iterator: reads from input stream ---

cout << "\n=== istream_iterator (from string stream) ===" << endl;

istringstream ss("10 20 30 40 50");

vector<int> fromStream;

copy(istream_iterator<int>(ss), // Start reading

istream_iterator<int>(), // End sentinel (default-constructed)

back_inserter(fromStream));

cout << "Read from stream: ";

for (int n : fromStream) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// --- move_iterator: transfers ownership instead of copying ---

cout << "\n=== move_iterator ===" << endl;

vector<string> strSrc = {"one", "two", "three", "four"};

vector<string> strDst;

move(strSrc.begin(), strSrc.end(), back_inserter(strDst));

cout << "Moved strings: ";

for (const string& s : strDst) cout << s << " ";

cout << endl;

cout << "Source after move (empty strings): ";

for (const string& s : strSrc) cout << "'" << s << "' ";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- back_inserter(dst): Returns an output iterator that calls dst.push_back() for each assignment

- Grows automatically: No pre-sizing needed — adaptor expands the container

- copy without back_inserter crash: Writing to dst.begin() on empty vector is undefined behavior

- copy_if with back_inserter: Filter and collect pattern — evens appended as found

- front_inserter(lst): Output iterator that calls lst.push_front() — prepends each element

- Reversal side effect: Inserting 1,2,3,4,5 at front gives 5,4,3,2,1 — last-in is at front

- Only works with containers having push_front: vector doesn’t have push_front — use list or deque

- inserter(target, pos): Inserts at specified position — pos is iterator into target

- Position shifts: Each insertion at pos pushes subsequent elements right

- ostream_iterator<string>(cout, ” “): Writes each element to cout followed by delimiter

- Delimiter customization: Change ” ” to “, ” or “\n” for different formatting

- istream_iterator<int>(ss): Reads integers from istringstream using >>

- Default-constructed sentinel:

istream_iterator<int>()is the “end of stream” sentinel - move_iterator / std::move: Moves elements instead of copying — O(1) per element for strings

- Source elements after move: In valid but unspecified state — typically empty strings

Output:

=== back_inserter ===

Copied to empty vector: 1 2 3 4 5

Filtered evens: 2 4

=== front_inserter ===

front_inserter result (reversed): 5 4 3 2 1

copy with front_inserter (reversed): 5 4 3 2 1

=== inserter ===

After inserting src at position 1: 10 1 2 3 4 5 20 30

=== ostream_iterator ===

Hello World from C++

1, 2, 3, 4, 5,

=== istream_iterator (from string stream) ===

Read from stream: 10 20 30 40 50

=== move_iterator ===

Moved strings: one two three four

Source after move (empty strings): '' '' '' ''Iterator Helper Functions

The <iterator> header provides utility functions for working with iterators generically.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <list>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// --- std::advance: move iterator by n steps ---

cout << "=== std::advance ===" << endl;

list<int> lst = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

auto it = lst.begin();

cout << "Start: " << *it << endl;

advance(it, 3); // Move forward 3 steps

cout << "After advance(it, 3): " << *it << endl;

advance(it, -2); // Move backward 2 steps (only for bidirectional+)

cout << "After advance(it, -2): " << *it << endl;

// advance works on any iterator type — adapts to capability

vector<int> vec = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

auto vecIt = vec.begin();

advance(vecIt, 4); // O(1) for random-access, O(n) for list

cout << "Vector advance(4): " << *vecIt << endl;

// --- std::distance: count steps between two iterators ---

cout << "\n=== std::distance ===" << endl;

vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

auto first = v.begin();

auto last = v.end();

cout << "distance(begin, end): " << distance(first, last) << endl;

auto mid = v.begin() + 2;

cout << "distance(begin, begin+2): " << distance(first, mid) << endl;

cout << "distance(begin+2, end): " << distance(mid, last) << endl;

// List distance — O(n) since iterators aren't random-access

list<int> lst2 = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7};

auto lstFirst = lst2.begin();

auto lstLast = lst2.end();

cout << "List distance: " << distance(lstFirst, lstLast) << endl;

// --- std::next and std::prev ---

cout << "\n=== std::next and std::prev ===" << endl;

vector<int> nv = {10, 20, 30, 40, 50};

auto nit = nv.begin();

auto second = next(nit); // One step forward (doesn't modify nit)

auto third = next(nit, 2); // Two steps forward

auto last2 = prev(nv.end()); // One step backward from end

auto fourth = prev(nv.end(), 2); // Two steps backward

cout << "next(begin): " << *second << endl;

cout << "next(begin, 2): " << *third << endl;

cout << "prev(end): " << *last2 << endl;

cout << "prev(end, 2): " << *fourth << endl;

cout << "Original nit unchanged: " << *nit << endl;

// --- Practical: safe last-element access ---

cout << "\n=== Safe last-element access ===" << endl;

vector<int> safeV = {100, 200, 300};

if (!safeV.empty()) {

cout << "Last element: " << *prev(safeV.end()) << endl;

// Equivalent to: safeV.back()

}

// --- iter_swap: swap elements pointed to by two iterators ---

cout << "\n=== std::iter_swap ===" << endl;

vector<int> sw = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

cout << "Before iter_swap: ";

for (int n : sw) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

iter_swap(sw.begin(), sw.begin() + 4); // Swap first and last

cout << "After iter_swap(begin, begin+4): ";

for (int n : sw) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- advance(it, n): Moves iterator forward by n steps — works for any iterator category

- advance(it, -2): Moves backward — only works for bidirectional and random-access iterators

- Adapts to capability: For random-access, advance uses += (O(1)); for list, loops step-by-step (O(n))

- Why advance?: Generic code can use advance without knowing iterator category

- distance(first, last): Counts steps from first to last — first must be reachable from second

- O(1) for random-access: Computed as

last - firstdirectly - O(n) for bidirectional: Must step through each element

- Sub-range distances: distance(begin, mid) + distance(mid, end) = distance(begin, end)

- std::next(it): Returns new iterator one step forward — does NOT modify original it

- std::next(it, n): Returns iterator n steps forward — non-modifying

- std::prev(it): Returns iterator one step backward — non-modifying

- prev(v.end()): Standard idiom for “iterator to last element” — cleaner than v.end()-1

- next/prev don’t modify: Original iterator unchanged — safer than manually applying advance

- iter_swap(it1, it2): Swaps the VALUES pointed to by two iterators — standard swap under the hood

Output:

=== std::advance ===

Start: 10

After advance(it, 3): 40

After advance(it, -2): 20

Vector advance(4): 5

=== std::distance ===

distance(begin, end): 5

distance(begin, begin+2): 2

distance(begin+2, end): 3

List distance: 7

=== std::next and std::prev ===

next(begin): 20

next(begin, 2): 30

prev(end): 50

prev(end, 2): 40

Original nit unchanged: 10

=== Safe last-element access ===

Last element: 300

=== std::iter_swap ===

Before iter_swap: 1 2 3 4 5

After iter_swap(begin, begin+4): 5 2 3 4 1Writing a Custom Iterator

For your own container types, you can write a custom iterator by implementing the required interface.

#include <iostream>

#include <iterator>

#include <algorithm>

using namespace std;

// Simple fixed-size ring buffer

template <typename T, size_t N>

class RingBuffer {

private:

T data[N];

size_t head = 0;

size_t count = 0;

public:

void push(const T& value) {

data[(head + count) % N] = value;

if (count < N) ++count;

else head = (head + 1) % N; // Overwrite oldest

}

size_t size() const { return count; }

// --- Forward Iterator ---

class Iterator {

private:

const RingBuffer* buf;

size_t index; // Logical index (0 = oldest element)

public:

// Required type aliases for iterator_traits

using iterator_category = forward_iterator_tag;

using value_type = T;

using difference_type = ptrdiff_t;

using pointer = const T*;

using reference = const T&;

Iterator(const RingBuffer* b, size_t i) : buf(b), index(i) {}

// Dereference: return element at logical index

reference operator*() const {

return buf->data[(buf->head + index) % N];

}

// Arrow operator

pointer operator->() const {

return &(operator*());

}

// Pre-increment

Iterator& operator++() {

++index;

return *this;

}

// Post-increment

Iterator operator++(int) {

Iterator tmp = *this;

++(*this);

return tmp;

}

// Equality comparisons

bool operator==(const Iterator& other) const { return index == other.index; }

bool operator!=(const Iterator& other) const { return !(*this == other); }

};

Iterator begin() const { return Iterator(this, 0); }

Iterator end() const { return Iterator(this, count); }

};

int main() {

cout << "=== Custom RingBuffer Iterator ===" << endl;

RingBuffer<int, 5> ring;

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) ring.push(i);

cout << "Ring buffer (1-5): ";

for (int n : ring) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// Push two more — oldest elements overwritten

ring.push(6);

ring.push(7);

cout << "After pushing 6, 7: ";

for (int n : ring) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// STL algorithms work with our custom iterator!

cout << "\n=== STL algorithms with custom iterator ===" << endl;

auto it = find(ring.begin(), ring.end(), 5);

if (it != ring.end()) cout << "Found: " << *it << endl;

int total = 0;

for (int n : ring) total += n;

cout << "Sum: " << total << endl;

int cnt = count_if(ring.begin(), ring.end(), [](int n){ return n > 4; });

cout << "Elements > 4: " << cnt << endl;

return 0;

}Step-by-step explanation:

- RingBuffer class: Fixed-size circular buffer — overwrites oldest element when full

- head / count: Track the oldest element position and number of stored elements

- % N arithmetic: Wraps around at capacity — creates the “ring” behavior

- Iterator nested class: Defined inside RingBuffer — has access to private members

- iterator_category = forward_iterator_tag: Tells STL this is a forward iterator

- Five required type aliases: iterator_category, value_type, difference_type, pointer, reference

- iterator_traits: STL uses these aliases to adapt algorithm behavior to iterator category

- *operator()**: Returns const reference to element at logical index position

- (buf->head + index) % N: Converts logical index to physical array index

- operator++() pre-increment: Advances logical index, returns *this reference

- operator++(int) post-increment: Saves copy before increment, returns old position

- operator== and !=: Equality based on logical index — enables range comparison

- begin() returns index 0: Points to oldest element (at head)

- end() returns index count: One-past-last logical position

- STL algorithms work immediately: find(), count_if() use our operator* and operator++ seamlessly

Output:

=== Custom RingBuffer Iterator ===-

Ring buffer (1-5): 1 2 3 4 5

After pushing 6, 7: 3 4 5 6 7

=== STL algorithms with custom iterator ===

Found: 5

Sum: 25

Elements > 4: 3Iterator Category Summary and Container Mapping

| Container | Iterator Category | Supports |

|---|---|---|

| vector | Random-access | ++, –, +n, -n, [], <, > |

| deque | Random-access | ++, –, +n, -n, [], <, > |

| array | Random-access | ++, –, +n, -n, [], <, > |

| list | Bidirectional | ++, — |

| set / map | Bidirectional | ++, — |

| unordered_set / unordered_map | Forward | ++ only |

| forward_list | Forward | ++ only |

| istream_iterator | Input | ++ (read only) |

| ostream_iterator | Output | ++ (write only) |

| back_inserter | Output | ++ (write only) |

Common Iterator Pitfalls

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

int main() {

// PITFALL 1: Dereferencing end()

vector<int> v = {1, 2, 3};

// auto it = v.end();

// cout << *it; // UNDEFINED BEHAVIOR — end() points past last element

// FIX: Always check before dereferencing

auto it = v.end();

if (it != v.begin()) {

--it;

cout << "Last element: " << *it << endl; // Safe

}

// PITFALL 2: Iterator invalidation after push_back

vector<int> growing = {1, 2, 3};

auto savedIt = growing.begin();

growing.push_back(4); // May trigger reallocation!

// cout << *savedIt; // UNDEFINED BEHAVIOR — iterator may be dangling

cout << "After push_back, don't use saved iterators" << endl;

// FIX: Re-obtain iterator after modification

auto freshIt = growing.begin();

cout << "Fresh iterator is safe: " << *freshIt << endl;

// PITFALL 3: Modifying container while iterating

vector<int> nums = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

// for (auto it2 = nums.begin(); it2 != nums.end(); ++it2) {

// if (*it2 == 3) nums.erase(it2); // UNDEFINED BEHAVIOR

// }

// FIX: Use erase return value

for (auto it2 = nums.begin(); it2 != nums.end(); ) {

if (*it2 == 3) {

it2 = nums.erase(it2); // erase returns next valid iterator

} else {

++it2;

}

}

cout << "After safe erase of 3: ";

for (int n : nums) cout << n << " ";

cout << endl;

// PITFALL 4: Using < instead of != for non-random-access

// list<int> lst = {1,2,3};

// for (auto it = lst.begin(); it < lst.end(); ++it) // ERROR: < not supported

// FIX: Always use != for generic code

cout << "Always use != for generic iterator loops" << endl;

return 0;

}Common pitfall explanations:

- Dereferencing end(): end() is a sentinel — it points past the last element, there’s nothing there

- Check before dereference: Always verify iterator != end() before using *it

- Iterator invalidation: push_back may trigger reallocation — all vector iterators invalidated

- Save index, not iterator: If you need to remember position, save the index

i, not iterator - Erase during loop: Direct erase invalidates the iterator — loop crashes or skips elements

- erase return value:

it = erase(it)gives valid iterator to next element after erased - < comparison for non-random: list iterators don’t support < — use != universally

- Generic code: Always write

!= end()to work with any iterator category

Conclusion: Thinking in Iterators

Iterators are the architectural cornerstone of the STL—the concept that makes everything work together. Once you truly understand iterators, you understand why the STL is designed the way it is, and you can leverage its full power rather than fighting against it.

Key takeaways:

- Iterators are pointer-like objects providing a uniform interface for container traversal

- Five categories: input (read, single-pass), output (write, single-pass), forward (read/write, multi-pass), bidirectional (+ reverse), random-access (+ arithmetic and comparison)

- begin()/end() define the range; rbegin()/rend() traverse in reverse; cbegin()/cend() enforce read-only access

- Iterator adaptors: back_inserter (appends), front_inserter (prepends), inserter (at position), ostream_iterator, istream_iterator

- Helper functions: advance() moves by n, distance() counts steps, next()/prev() return new iterators without modifying original

- Always use != end() as loop condition — relational < only works for random-access iterators

- Iterator invalidation: inserting into vector, erasing from any container — re-obtain iterators after modifications

- Custom iterators: implement five type aliases plus operators (*, ++, ==, !=) to make your container work with all STL algorithms

- Use std::begin(x) free functions in generic code — works on both containers and plain arrays

Understanding iterators transforms you from a C++ user to a C++ developer who understands the STL’s design and can extend it with confidence.