C++ provides fundamental data types like integers, doubles, and characters that let you represent basic values, but real-world programs work with concepts far more complex than individual numbers. When you’re building a banking application, you need to represent accounts with balances, transaction histories, and account holders. When you’re creating a game, you need characters with positions, health points, inventory items, and abilities. Built-in types cannot directly represent these complex entities because each concept combines multiple pieces of related data with operations that work on that data. Classes solve this problem by enabling you to create your own custom data types that bundle related data and functionality together, letting you model real-world concepts directly in code.

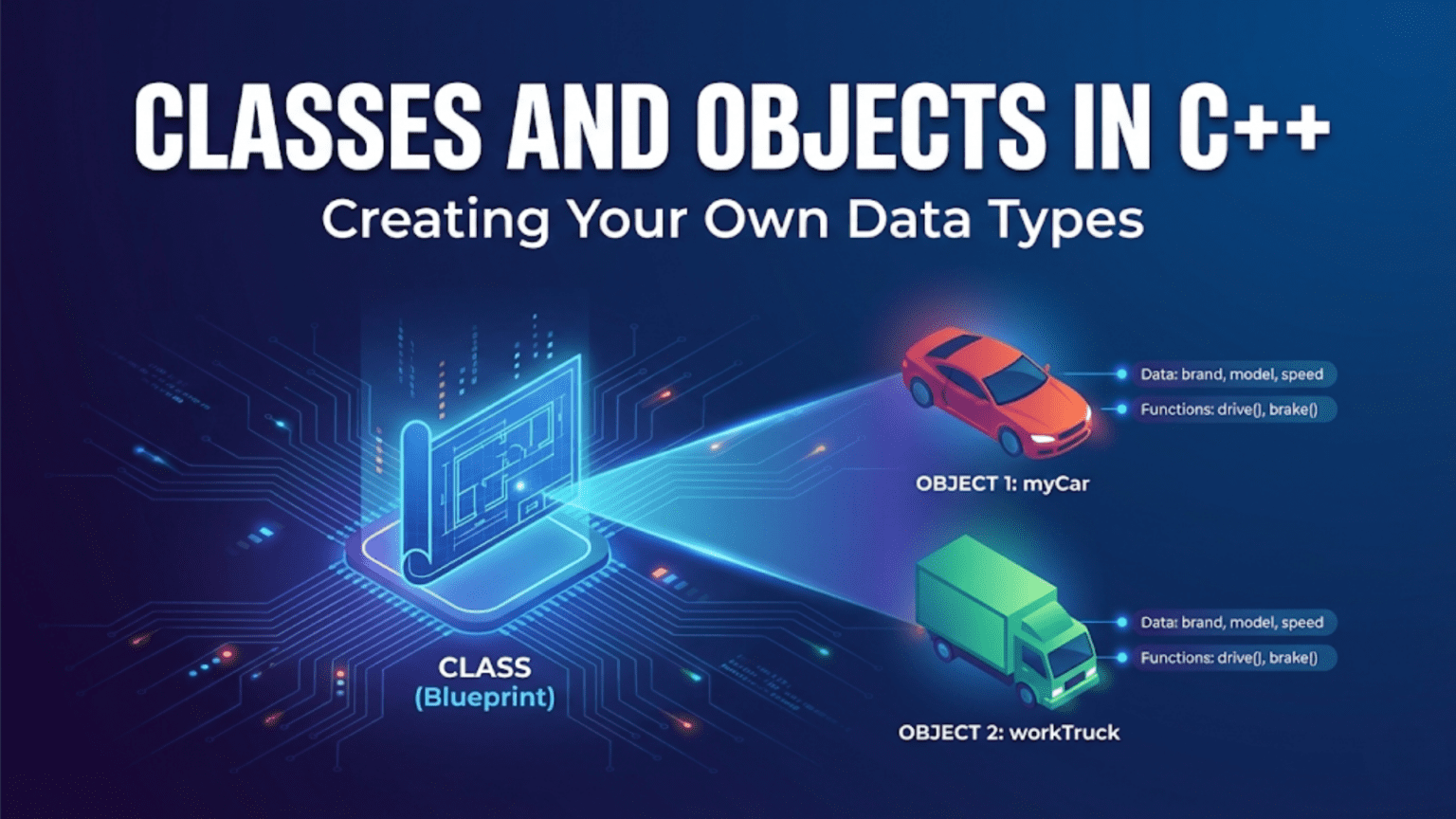

Think of classes as blueprints or templates for creating things. Just as an architect creates a blueprint for a house that specifies the number of rooms, their sizes, and how they connect, a class defines the structure and behavior of a new type. The blueprint itself is not a house, but you can build many houses from the same blueprint, with each house being an independent instance that follows the blueprint’s design. Similarly, a class is not an object but rather the definition of what objects of that type will contain and how they will behave. Each object you create from the class is an independent instance with its own data, but all instances share the same structure and capabilities defined by the class.

The power of classes comes from abstraction and encapsulation working together. You define what data an object contains through member variables, what operations it supports through member functions, and what parts are accessible from outside the class through access specifiers. This creates types that behave like built-in types, with the same intuitive usage patterns. You can create a BankAccount variable just like you create an integer variable, call methods on it just like you call functions, and let the class handle all the complexity of maintaining consistent state. Understanding how to design and implement effective classes transforms you from someone who uses types others created to someone who creates types that others can use, enabling you to build abstractions that make complex programs manageable.

Let me start by showing you the basic anatomy of a class, demonstrating how to define a class and create objects from it:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

// Class definition - the blueprint

class Book {

private:

// Member variables - the data each Book object contains

std::string title;

std::string author;

int pages;

double price;

public:

// Member functions - operations that work on Book objects

// Initialize a Book with values

void initialize(const std::string& t, const std::string& a, int p, double pr) {

title = t;

author = a;

pages = p;

price = pr;

}

// Display book information

void display() const {

std::cout << "\"" << title << "\" by " << author << std::endl;

std::cout << "Pages: " << pages << ", Price: $" << price << std::endl;

}

// Apply a discount

void applyDiscount(double percentage) {

if (percentage > 0 && percentage < 100) {

price = price * (1 - percentage / 100.0);

std::cout << "Discount applied. New price: $" << price << std::endl;

}

}

// Get the price

double getPrice() const {

return price;

}

// Check if book is long

bool isLongBook() const {

return pages > 500;

}

};

int main() {

// Creating objects - instances of the Book class

Book book1; // book1 is an object of type Book

Book book2; // book2 is another independent object

// Initialize the objects with data

book1.initialize("The C++ Programming Language", "Bjarne Stroustrup", 1376, 79.99);

book2.initialize("Clean Code", "Robert Martin", 464, 44.99);

// Use the objects by calling their member functions

std::cout << "=== Book 1 ===" << std::endl;

book1.display();

std::cout << "Is long book? " << (book1.isLongBook() ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

std::cout << "\n=== Book 2 ===" << std::endl;

book2.display();

// Apply discount to book1 only

std::cout << "\nApplying 20% discount to book1..." << std::endl;

book1.applyDiscount(20);

// Each object maintains its own data

std::cout << "\nBook prices after discount:" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Book 1: $" << book1.getPrice() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Book 2: $" << book2.getPrice() << std::endl;

return 0;

}The class definition starts with the class keyword followed by the class name, then curly braces containing the class body. Inside, you define member variables that hold the data each object will contain, and member functions that define operations objects can perform. The semicolon after the closing brace is required, which catches many beginners by surprise. Once you define the class, you can create objects of that type just like you create variables of built-in types. Each object gets its own copy of the member variables, so modifying book one’s price does not affect book two’s price. The member functions operate on whichever object you call them on, accessed using the dot operator.

Access specifiers control what parts of a class are accessible from outside the class. The three access specifiers are private, protected, and public, with private meaning accessible only within the class itself, public meaning accessible from anywhere, and protected being accessible within the class and derived classes. Proper use of access specifiers implements encapsulation by hiding internal details while exposing a clean public interface:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class BankAccount {

private:

// Private members - hidden from outside code

std::string accountNumber;

std::string ownerName;

double balance;

int transactionCount;

// Private helper function - only used internally

void logTransaction(const std::string& type, double amount) {

transactionCount++;

std::cout << "[Log] Transaction #" << transactionCount

<< ": " << type << " $" << amount << std::endl;

}

public:

// Public interface - how external code interacts with BankAccount

void initialize(const std::string& accNum, const std::string& owner, double initial) {

accountNumber = accNum;

ownerName = owner;

balance = (initial > 0) ? initial : 0;

transactionCount = 0;

std::cout << "Account " << accountNumber << " created for " << ownerName << std::endl;

}

void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount <= 0) {

std::cout << "Invalid deposit amount" << std::endl;

return;

}

balance += amount;

logTransaction("Deposit", amount);

std::cout << "Deposited $" << amount << ". New balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

}

bool withdraw(double amount) {

if (amount <= 0) {

std::cout << "Invalid withdrawal amount" << std::endl;

return false;

}

if (amount > balance) {

std::cout << "Insufficient funds" << std::endl;

return false;

}

balance -= amount;

logTransaction("Withdrawal", amount);

std::cout << "Withdrew $" << amount << ". New balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

return true;

}

double getBalance() const {

return balance;

}

void displayInfo() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Account Information ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Account Number: " << accountNumber << std::endl;

std::cout << "Owner: " << ownerName << std::endl;

std::cout << "Balance: $" << balance << std::endl;

std::cout << "Total Transactions: " << transactionCount << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

BankAccount account1;

BankAccount account2;

account1.initialize("ACC001", "Alice Johnson", 1000.0);

account2.initialize("ACC002", "Bob Smith", 500.0);

// Can only access public members

account1.deposit(500);

account1.withdraw(200);

// Cannot access private members

// account1.balance = 1000000; // Compilation error!

// account1.logTransaction("Hack", 999999); // Compilation error!

// Must use public interface

std::cout << "Account 1 balance: $" << account1.getBalance() << std::endl;

account1.displayInfo();

account2.displayInfo();

return 0;

}Making the balance private prevents external code from arbitrarily changing it, ensuring all modifications go through the deposit and withdraw methods that validate amounts and maintain accurate transaction counts. The private log transaction helper function encapsulates internal bookkeeping that external code should not call directly. This access control creates a boundary between what the class promises to maintain and what external code can rely on. You can change private implementation details without breaking code that uses the class, as long as the public interface remains consistent.

The const keyword on member functions indicates they do not modify the object’s state, which is important for const-correctness and enables calling those functions on const objects:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <cmath>

class Point {

private:

double x;

double y;

public:

void initialize(double xVal, double yVal) {

x = xVal;

y = yVal;

}

// Const member functions - do not modify the object

double getX() const {

return x;

}

double getY() const {

return y;

}

double distanceFromOrigin() const {

return std::sqrt(x * x + y * y);

}

double distanceTo(const Point& other) const {

double dx = x - other.x;

double dy = y - other.y;

return std::sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy);

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "(" << x << ", " << y << ")";

}

// Non-const member functions - modify the object

void move(double dx, double dy) {

x += dx;

y += dy;

}

void setX(double newX) {

x = newX;

}

void setY(double newY) {

y = newY;

}

};

// Function taking const reference

void printPoint(const Point& p) {

std::cout << "Point: ";

p.display(); // OK - display is const

std::cout << ", Distance from origin: " << p.distanceFromOrigin() << std::endl;

// Cannot call non-const functions on const object

// p.move(1, 1); // Compilation error!

}

int main() {

Point p1;

p1.initialize(3, 4);

// Can call both const and non-const functions on non-const object

std::cout << "X coordinate: " << p1.getX() << std::endl;

p1.move(1, 1);

printPoint(p1);

// Const object can only call const member functions

const Point p2 = p1;

std::cout << "Const point Y: " << p2.getY() << std::endl;

// p2.move(1, 1); // Compilation error - move is not const!

return 0;

}Mark member functions const when they do not modify any member variables. This enables calling them on const objects and documents that the function does not change state, which helps both compilers and human readers understand your code’s behavior. Functions that access member variables through const references can also call const member functions on those referenced objects, creating a chain of const-correctness throughout your program.

Member variables can have default values, and you can provide multiple ways to initialize objects to make them easier to use:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Configuration {

private:

std::string serverAddress;

int port;

bool enableLogging;

int maxConnections;

public:

// Initialize with all parameters

void initialize(const std::string& addr, int p, bool logging, int maxConn) {

serverAddress = addr;

port = p;

enableLogging = logging;

maxConnections = maxConn;

}

// Initialize with defaults for some parameters

void initializeDefaults(const std::string& addr) {

serverAddress = addr;

port = 8080; // Default port

enableLogging = true; // Default logging enabled

maxConnections = 100; // Default max connections

}

void display() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Configuration ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Server: " << serverAddress << ":" << port << std::endl;

std::cout << "Logging: " << (enableLogging ? "Enabled" : "Disabled") << std::endl;

std::cout << "Max Connections: " << maxConnections << std::endl;

}

void setPort(int p) {

if (p > 0 && p < 65536) {

port = p;

}

}

void setLogging(bool enabled) {

enableLogging = enabled;

}

};

int main() {

Configuration config1;

Configuration config2;

// Full initialization

config1.initialize("192.168.1.100", 9000, false, 200);

// Default initialization

config2.initializeDefaults("localhost");

config1.display();

config2.display();

// Modify specific settings

config2.setPort(3000);

config2.setLogging(false);

std::cout << "\nAfter modifications:" << std::endl;

config2.display();

return 0;

}Providing different initialization methods gives users flexibility in how they create and set up objects. The initialize defaults method uses sensible default values for most parameters, requiring users to specify only the essential server address. The setter methods allow modifying individual settings after initialization. This approach makes the class easier to use by not forcing users to specify every detail when defaults are often appropriate.

Let me show you a more comprehensive example that demonstrates building a complete class with multiple responsibilities working together:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class Student {

private:

std::string name;

int studentId;

std::vector<double> grades;

std::string major;

int creditsCompleted;

// Private helper to calculate sum

double calculateGradeSum() const {

double sum = 0;

for (double grade : grades) {

sum += grade;

}

return sum;

}

public:

// Initialize student with basic information

void initialize(const std::string& studentName, int id, const std::string& studentMajor) {

name = studentName;

studentId = id;

major = studentMajor;

creditsCompleted = 0;

std::cout << "Student " << name << " (ID: " << studentId << ") enrolled in "

<< major << std::endl;

}

// Add a grade

void addGrade(double grade) {

if (grade >= 0 && grade <= 100) {

grades.push_back(grade);

std::cout << "Grade " << grade << " added for " << name << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Invalid grade. Must be between 0 and 100." << std::endl;

}

}

// Calculate GPA

double calculateGPA() const {

if (grades.empty()) {

return 0.0;

}

double average = calculateGradeSum() / grades.size();

// Convert percentage to 4.0 scale

if (average >= 90) return 4.0;

if (average >= 80) return 3.0;

if (average >= 70) return 2.0;

if (average >= 60) return 1.0;

return 0.0;

}

// Get letter grade

char getLetterGrade() const {

if (grades.empty()) return 'F';

double average = calculateGradeSum() / grades.size();

if (average >= 90) return 'A';

if (average >= 80) return 'B';

if (average >= 70) return 'C';

if (average >= 60) return 'D';

return 'F';

}

// Add completed credits

void completeCredits(int credits) {

if (credits > 0) {

creditsCompleted += credits;

std::cout << name << " completed " << credits << " credits" << std::endl;

}

}

// Check graduation eligibility

bool canGraduate() const {

return creditsCompleted >= 120 && calculateGPA() >= 2.0;

}

// Display full student report

void displayReport() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Student Report ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Name: " << name << std::endl;

std::cout << "ID: " << studentId << std::endl;

std::cout << "Major: " << major << std::endl;

std::cout << "Credits Completed: " << creditsCompleted << std::endl;

std::cout << "Number of Grades: " << grades.size() << std::endl;

if (!grades.empty()) {

std::cout << "Average: " << (calculateGradeSum() / grades.size()) << "%" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Letter Grade: " << getLetterGrade() << std::endl;

std::cout << "GPA: " << calculateGPA() << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "Graduation Status: " << (canGraduate() ? "Eligible" : "Not Eligible") << std::endl;

}

// Getters

std::string getName() const { return name; }

int getId() const { return studentId; }

std::string getMajor() const { return major; }

int getCredits() const { return creditsCompleted; }

};

class Course {

private:

std::string courseName;

std::string courseCode;

int maxStudents;

std::vector<Student*> enrolledStudents;

public:

void initialize(const std::string& name, const std::string& code, int maxEnrollment) {

courseName = name;

courseCode = code;

maxStudents = maxEnrollment;

std::cout << "Course created: " << courseCode << " - " << courseName << std::endl;

}

bool enrollStudent(Student* student) {

if (enrolledStudents.size() >= maxStudents) {

std::cout << "Course is full" << std::endl;

return false;

}

enrolledStudents.push_back(student);

std::cout << student->getName() << " enrolled in " << courseCode << std::endl;

return true;

}

void displayCourseInfo() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Course Information ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Course: " << courseCode << " - " << courseName << std::endl;

std::cout << "Enrolled: " << enrolledStudents.size() << "/" << maxStudents << std::endl;

if (!enrolledStudents.empty()) {

std::cout << "Students:" << std::endl;

for (const auto* student : enrolledStudents) {

std::cout << " - " << student->getName() << " (" << student->getMajor() << ")" << std::endl;

}

}

}

int getEnrollmentCount() const {

return enrolledStudents.size();

}

};

int main() {

// Create students

Student student1, student2, student3;

student1.initialize("Alice Johnson", 1001, "Computer Science");

student2.initialize("Bob Smith", 1002, "Mathematics");

student3.initialize("Carol White", 1003, "Computer Science");

// Add grades

student1.addGrade(92);

student1.addGrade(88);

student1.addGrade(95);

student1.completeCredits(60);

student2.addGrade(78);

student2.addGrade(82);

student2.addGrade(75);

student2.completeCredits(45);

student3.addGrade(95);

student3.addGrade(98);

student3.addGrade(97);

student3.completeCredits(125);

// Display reports

student1.displayReport();

student2.displayReport();

student3.displayReport();

// Create courses

Course course1, course2;

course1.initialize("Data Structures", "CS201", 30);

course2.initialize("Algorithms", "CS301", 25);

// Enroll students

std::cout << "\n=== Course Enrollment ===" << std::endl;

course1.enrollStudent(&student1);

course1.enrollStudent(&student2);

course1.enrollStudent(&student3);

course2.enrollStudent(&student1);

course2.enrollStudent(&student3);

// Display course info

course1.displayCourseInfo();

course2.displayCourseInfo();

return 0;

}This comprehensive example shows how classes can represent complex real-world concepts. The Student class manages grades, calculates GPAs, tracks credits, and determines graduation eligibility, with all the complexity hidden behind a clean interface. The Course class manages enrollment and maintains relationships with students. Each class has clear responsibilities, with private helper methods handling internal complexity and public methods providing the interface external code uses. The classes work together through composition, where courses contain references to students, demonstrating how objects collaborate to build larger systems.

Understanding the relationship between classes and objects is fundamental. The class is the type definition, the blueprint that describes structure and behavior. Objects are instances of that type, actual variables that occupy memory and maintain state. You can create as many objects as needed from a single class, just as you create multiple integer variables from the int type. Each object has its own member variables with independent values, but all objects of a class share the same member functions, with the member functions operating on whichever object called them.

Member functions can call other member functions of the same class, and they can access all members including private ones because they are part of the class:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Rectangle {

private:

double width;

double height;

// Private validation helper

bool isValidDimension(double dimension) const {

return dimension > 0;

}

public:

void initialize(double w, double h) {

if (isValidDimension(w) && isValidDimension(h)) {

width = w;

height = h;

} else {

std::cout << "Invalid dimensions. Setting to 1x1." << std::endl;

width = 1;

height = 1;

}

}

double getArea() const {

return width * height;

}

double getPerimeter() const {

return 2 * (width + height);

}

double getDiagonal() const {

return std::sqrt(width * width + height * height);

}

// Member function calling other member functions

void displayFullInfo() const {

std::cout << "\n=== Rectangle Information ===" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Dimensions: " << width << " x " << height << std::endl;

std::cout << "Area: " << getArea() << std::endl; // Calls member function

std::cout << "Perimeter: " << getPerimeter() << std::endl; // Calls member function

std::cout << "Diagonal: " << getDiagonal() << std::endl; // Calls member function

}

void resize(double widthFactor, double heightFactor) {

double newWidth = width * widthFactor;

double newHeight = height * heightFactor;

// Calls private helper function

if (isValidDimension(newWidth) && isValidDimension(newHeight)) {

width = newWidth;

height = newHeight;

std::cout << "Resized to " << width << " x " << height << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "Invalid resize factors" << std::endl;

}

}

bool isSquare() const {

return width == height;

}

};

int main() {

Rectangle rect;

rect.initialize(5, 10);

rect.displayFullInfo();

std::cout << "\nIs square? " << (rect.isSquare() ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

rect.resize(2, 1.5);

rect.displayFullInfo();

return 0;

}The display full info method calls get area, get perimeter, and get diagonal to gather information to display, demonstrating how member functions build on each other. The resize method calls the private is valid dimension helper to validate new dimensions before applying them. This ability for member functions to use other member functions and access private members creates cohesive classes where related functionality works together naturally.

Key Takeaways

Classes enable creating custom data types that bundle related data and functionality together, with class definitions serving as blueprints from which you create independent object instances. Each object has its own copy of member variables maintaining independent state, while member functions define operations objects can perform and are called using the dot operator on specific objects. Class definitions require a semicolon after the closing brace, catching many beginners who forget this syntax requirement.

Access specifiers control visibility and implement encapsulation, with private members accessible only within the class, public members accessible from anywhere, and protected members accessible within the class and derived classes. Making data members private and providing public member functions creates clean interfaces that hide implementation details, enabling you to change internal representation without breaking external code while maintaining data integrity through validated access.

The const keyword on member functions indicates they do not modify object state, enabling their use on const objects and documenting that the function is read-only. Member functions can call other member functions and access all members including private ones because they are part of the class itself. Understanding how to design effective classes with appropriate encapsulation, clear interfaces, and well-organized responsibilities transforms you from using types others created to creating types that model your problem domain directly, making complex programs manageable through well-designed abstractions.