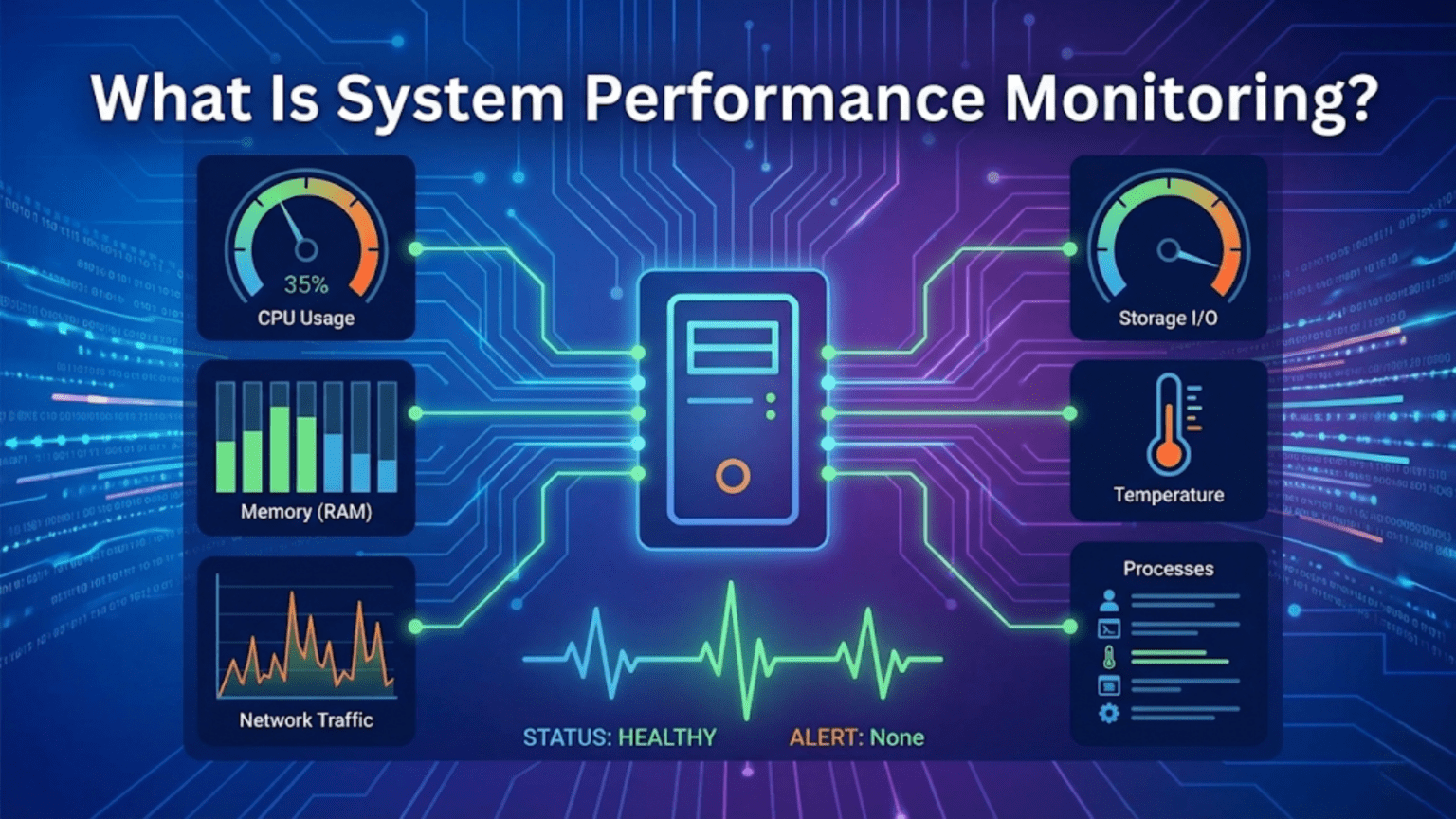

System performance monitoring is the continuous measurement and analysis of key hardware and software metrics—including CPU usage, memory consumption, disk I/O, network throughput, and application response times—to understand how a computer system is operating, identify resource bottlenecks, diagnose performance problems, plan capacity, and ensure applications and services meet their performance requirements. Operating systems provide built-in tools and instrumentation that collect these metrics, and both real-time and historical data help administrators and developers make informed decisions about optimization and resource allocation.

Every computer system has finite resources—processor cycles, memory, storage bandwidth, and network capacity—and the applications running on it compete for those resources constantly. When your computer feels sluggish, when a server starts responding slowly, when an application takes unexpectedly long to complete a task, or when you want to understand whether your hardware is adequate for your workload, you need visibility into how resources are being used. System performance monitoring provides that visibility by continuously measuring resource utilization and application behavior, translating the invisible flows of data and computation into understandable metrics that reveal what’s happening inside a running system.

Performance monitoring spans a spectrum from simple real-time observation (watching Task Manager to see which process is consuming all your CPU) to sophisticated long-term analysis (correlating weeks of metrics to identify patterns in server performance degradation). Modern operating systems provide rich instrumentation at every level, from hardware performance counters built into processors to application-level metrics exposed through monitoring APIs. Understanding performance monitoring—what metrics matter, what they mean, how to collect and interpret them, and what tools make the work practical—is essential knowledge for anyone responsible for system reliability or performance, from home users troubleshooting slow computers to enterprise administrators managing server fleets. This guide explores the fundamentals of system performance monitoring, the key metrics each resource generates, the built-in and third-party tools available across platforms, and how to interpret monitoring data to diagnose and resolve performance problems.

Why Performance Monitoring Matters

Performance monitoring is valuable in multiple distinct contexts, each with different goals and approaches.

Reactive troubleshooting uses monitoring to diagnose problems after they’re noticed. When users report that an application is slow, when a server starts dropping requests, or when a computer becomes unresponsive, monitoring tools help pinpoint the cause—which resource is saturated, which process is consuming it, and whether the problem is consistent or intermittent. Without monitoring data, performance troubleshooting is guesswork.

Proactive capacity planning uses historical performance data to predict future resource needs before problems occur. By tracking trends—memory usage growing 2% per month, disk filling at a consistent rate, CPU utilization reaching 80% during peak hours—administrators can plan hardware upgrades, application optimizations, or scaling decisions before capacity is exhausted. Capacity planning converts reactive crisis management into controlled, planned resource management.

Performance baselines establish what “normal” looks like for a system, making anomalies detectable. When you know a server normally uses 30% CPU under typical load, a sudden jump to 95% is immediately recognizable as abnormal—even before users notice problems. Without baselines, distinguishing normal from problematic behavior requires expert judgment rather than data comparison.

Application optimization uses performance data to guide development decisions. Profiling tools—specialized performance monitoring for code—identify which functions consume most execution time, which database queries are slow, and where memory is allocated. This data-driven approach prevents wasted effort on optimizing code paths that aren’t bottlenecks.

SLA (Service Level Agreement) compliance monitoring ensures services meet contractual performance commitments. Businesses that provide services to customers often commit to availability and performance standards—99.9% uptime, response times under 200ms. Continuous monitoring measures actual performance against these commitments, providing evidence of compliance or early warning of violations.

Cost optimization in cloud environments uses monitoring to identify underutilized resources. Virtual machines allocated more CPU and memory than their workloads actually use represent wasted spending. Monitoring reveals actual utilization, enabling rightsizing—reducing allocations to match actual needs, reducing cloud costs.

CPU Performance Metrics

CPU metrics reveal how processor resources are being used across different types of workloads and system states.

CPU utilization percentage is the most fundamental CPU metric—the fraction of time the CPU is doing useful work rather than idle. 0% means completely idle, 100% means continuously busy. Modern multi-core processors report both per-core utilization and aggregate utilization across all cores. A quad-core processor at 25% aggregate utilization might have one core at 100% while three are idle—important context that aggregate statistics hide. Sustained high CPU utilization (above 80-90%) indicates saturation where the processor can’t keep up with demand.

CPU usage breakdown by type reveals what the processor is doing. User mode CPU time is time spent executing application code. Kernel (system) mode CPU time is time spent executing operating system code on behalf of applications (handling system calls, interrupts, I/O). Idle time is time with nothing to execute. I/O wait (on Linux) indicates time the CPU is idle but waiting for I/O operations to complete—high I/O wait suggests storage or network bottlenecks rather than CPU bottlenecks. IRQ and softIRQ time represents interrupt handling overhead.

CPU run queue length (load average on Unix-like systems) indicates demand versus capacity. The run queue contains processes ready to execute but waiting for a CPU. A run queue length equal to the number of CPUs is fully utilized but not overloaded. Run queues longer than CPU count indicate more demand than capacity—processes wait in queue before executing. Linux’s load average shows run queue length averaged over 1, 5, and 15 minutes. A load average of 4.0 on a 4-core system indicates full utilization; 8.0 on the same system means processes wait on average one complete execution cycle before getting CPU time.

Context switch rate measures how frequently the OS switches execution between different processes or threads. Some context switching is normal and necessary for multitasking. Extremely high context switch rates indicate excessive thread contention, poorly designed thread pools, or thrashing caused by too many competing processes. High context switch overhead reduces effective CPU throughput because time switching between processes is time not doing useful work.

CPU frequency and thermal state affect actual processing capacity. Modern CPUs dynamically adjust clock speed based on load and temperature—running faster under load and slower when throttled by heat. Monitoring CPU frequency reveals whether the processor is running at full capacity or being thermally or power-limited. Unexpected frequency reduction under load indicates thermal or power issues requiring investigation.

Hardware performance counters built into modern processors provide extremely detailed CPU metrics including cache hit/miss rates (L1, L2, L3 caches), branch prediction accuracy, instructions per clock cycle (IPC), memory access latencies, and pipeline stalls. These low-level metrics are invaluable for performance-critical optimization but require specialized tools (perf on Linux, VTune on Windows) to access.

Memory Performance Metrics

Memory metrics reveal how RAM is being used, whether it’s sufficient for the workload, and whether the system is under memory pressure.

Physical memory usage shows how much RAM is currently in use versus available. Simple in-use versus free reporting can be misleading because modern operating systems aggressively use “free” memory for file system cache—memory holding recently accessed file data. This cached memory can be quickly reclaimed when applications need more RAM, so it’s not truly “wasted.” Better metrics distinguish between memory committed to processes (must be kept), memory used for cache (reclaimable), and truly free memory.

Virtual memory and swap usage indicates whether physical RAM is insufficient for the workload. When RAM fills, operating systems swap less-recently-used memory pages to disk (swap space on Linux, page file on Windows). Swap activity is orders of magnitude slower than RAM access, causing severe performance degradation. High swap usage or high swap I/O rates indicate memory pressure—the system is working around insufficient RAM. On SSDs, swap is less catastrophically slow than on HDDs, but still significantly impacts performance.

Page fault rate distinguishes between minor page faults (pages present in memory but needing table entries updated—cheap) and major page faults (pages not in memory, requiring disk access—expensive). High major page fault rates indicate active swapping or excessive file system page cache misses. Monitoring page fault rates helps distinguish memory pressure from other performance issues.

Memory bandwidth and latency measure how quickly data moves between CPU and RAM. Modern applications are often memory-bandwidth-limited—the CPU can process data faster than memory can supply it. Memory bandwidth monitoring (through hardware performance counters) reveals whether applications are memory-bound versus compute-bound. High memory latency indicates cache misses that force slow DRAM accesses.

Heap allocation metrics for specific processes or runtimes reveal memory management behavior. Growing heap size over time indicates memory leaks. High allocation rates indicate GC (garbage collection) pressure in managed runtimes. These application-level memory metrics complement OS-level metrics for understanding application behavior.

Per-process memory consumption shows which applications are using the most RAM, helping identify memory hogs or leaks. Different memory measurement methods give different values: RSS (Resident Set Size) shows physical RAM currently used by a process, VSZ (Virtual Size) includes all virtual memory allocations (including memory-mapped files and unused allocated but not accessed memory), and PSS (Proportional Set Size) on Linux accounts for shared memory proportionally. For identifying memory problems, RSS or PSS are most meaningful.

Storage Performance Metrics

Storage metrics reveal disk I/O patterns, utilization, and whether storage is a system bottleneck.

Disk I/O throughput measures how much data is being read from and written to storage per second. SSDs typically achieve 500MB/s to 7GB/s sequential throughput, while mechanical HDDs achieve 100-200MB/s. Throughput close to device maximums indicates storage saturation. Unexpectedly low throughput suggests I/O patterns don’t match device strengths (random I/O on spinning disks is much slower than sequential).

I/O Operations Per Second (IOPS) measures how many individual read/write operations storage performs per second. IOPS is often the binding constraint for database workloads and other applications performing many small random accesses. Enterprise SSDs handle hundreds of thousands of IOPS; consumer SSDs handle tens of thousands; spinning HDDs handle only 100-200 IOPS for random access. Monitoring IOPS versus device capability identifies storage saturation.

I/O latency measures how long individual storage operations take to complete, from request submission to data availability. Low latency (microseconds on NVMe SSDs, milliseconds on SATA SSDs, 5-15ms on spinning disks) is critical for interactive applications. Rising latency under load indicates storage saturation—the queue of pending I/O operations grows faster than the device can process them.

I/O queue depth measures how many I/O operations are pending at a given moment. Queue depth of zero means the device is idle. Queue depth consistently near device maximum indicates saturation. Most storage monitoring tools show average queue depth or queue depth percentile distributions.

Disk utilization percentage (different from I/O throughput) measures the fraction of time the storage device is busy processing I/O requests rather than idle. Like CPU utilization, 100% disk utilization indicates saturation regardless of whether throughput is high or low—the device has no spare capacity to process additional requests faster.

File system metadata operations (file creation, deletion, directory listing) have different performance characteristics than data reads and writes. Applications creating or deleting many small files may be bottlenecked on metadata operations rather than data throughput. Monitoring metadata operation rates helps distinguish these workload types.

Network Performance Metrics

Network metrics reveal data transfer rates, connection status, and whether network capacity is limiting application performance.

Network throughput (bandwidth) measures how much data is being transmitted and received per second through network interfaces. Comparing actual throughput to interface capacity (1Gbps, 10Gbps) reveals saturation. Unexpected low throughput despite high application demand indicates network bottlenecks, excessive retransmissions, or connection problems.

Network latency measures round-trip time between network endpoints—how long it takes for a packet to travel to a destination and a response to return. High latency degrades interactive application performance and reduces effective throughput for protocols with flow control (TCP throughput decreases with high latency). Latency monitoring distinguishes local network problems from internet connectivity issues.

Packet loss rate measures what fraction of transmitted packets are dropped before reaching their destination. Any packet loss degrades TCP performance (causing retransmissions and reducing throughput) and can cause noticeable quality issues for UDP-based applications like voice and video. Packet loss above 1-2% significantly impacts TCP performance.

Connection counts and connection state distribution reveal networking behavior. The number of established connections, connections in TIME_WAIT state, and connections queued for acceptance all provide insight into networking behavior. Accumulating TIME_WAIT connections indicate rapid connection establishment and teardown. Growing listen backlog indicates the application can’t accept connections as fast as they arrive.

Network errors including receive errors, transmit errors, dropped packets, and overruns indicate network interface problems, driver issues, or buffer exhaustion. Monitoring error rates alongside throughput distinguishes healthy from problematic network behavior.

Built-in OS Performance Monitoring Tools

Every major operating system includes built-in tools for observing performance, ranging from simple graphical utilities to powerful command-line analyzers.

Windows Task Manager (Ctrl+Shift+Esc) is the most accessible Windows performance monitor, providing real-time CPU, memory, disk, and network graphs plus per-process resource consumption. The Performance tab shows overall system resource usage with historical graphs. The Processes tab lists all running processes with their CPU, memory, disk, and network usage. The Details tab provides additional process information. Task Manager is the first tool Windows users reach for performance investigation.

Resource Monitor (resmon.exe) provides more detailed Windows performance data than Task Manager. It shows per-process CPU, disk, network, and memory usage with much greater granularity—which specific files each process is reading or writing, which network connections consume bandwidth, and which processes are accessing which memory regions. Resource Monitor is the tool for identifying exactly which application is responsible for specific resource usage.

Performance Monitor (perfmon.exe) is Windows’ comprehensive performance data collection and analysis tool. It can display hundreds of performance counters for every system component, log counter data over time for historical analysis, create data collector sets for automated monitoring, and generate performance reports. Performance Monitor is the tool for capacity planning and long-term performance analysis on Windows.

Windows Reliability Monitor (accessible through Control Panel or Performance Monitor) shows system stability history including application crashes, Windows errors, and information events on a timeline, helping correlate performance problems with specific events.

Linux provides multiple performance monitoring tools each specialized for different aspects. top and htop display processes sorted by resource usage with continuous refresh—htop adds color coding, mouse interaction, and easier process management. vmstat shows virtual memory, CPU, and I/O statistics as periodic snapshots. iostat (from sysstat package) provides detailed I/O statistics per device. sar (System Activity Reporter) records historical performance data and generates reports. netstat and ss show network connections and socket statistics. free shows memory usage. df and du show disk space. dstat combines multiple statistics in a single, configurable output.

The /proc and /sys virtual filesystems on Linux expose kernel performance data as files. /proc/cpu.info contains CPU information, /proc/mem.info shows detailed memory statistics, /proc/disk.stats provides I/O statistics, /proc/n.et/dev shows network interface statistics, and /proc/[p.id]/status provides per-process information. These pseudo-files are what monitoring tools read to gather performance data—direct access enables custom monitoring scripts without special privileges.

macOS Activity Monitor (Applications > Utilities) provides a graphical performance overview similar to Windows Task Manager, showing CPU, memory, energy, disk, and network usage per process and systemwide. The Memory pressure graph shows whether the system has adequate RAM. The Disk tab shows I/O rates per process. Activity Monitor is the primary macOS performance investigation tool.

The macOS Instruments application (part of Xcode) provides professional-grade performance analysis for application developers, offering time profiling, memory allocation tracking, Core Data performance analysis, and dozens of other measurement templates. Instruments goes far beyond system-level monitoring into application-specific performance profiling.

Third-Party Monitoring Tools

Beyond built-in OS tools, specialized monitoring software provides additional capabilities for professional environments.

Prometheus is an open-source monitoring and alerting toolkit widely used for monitoring servers and containerized applications. Prometheus scrapes metrics from instrumented applications and infrastructure components, stores them in a time-series database, and provides a powerful query language (PromQL) for analyzing metrics and defining alert conditions. Combined with Grafana for visualization, Prometheus+Grafana is the dominant open-source monitoring stack for cloud-native environments.

Grafana provides visualization and dashboarding for metrics from many sources including Prometheus, InfluxDB, Elasticsearch, and cloud providers. Grafana dashboards display time-series metrics as graphs, heatmaps, gauges, and other visualizations, enabling comprehensive performance visibility. Pre-built dashboards for common systems (Linux system metrics, Kubernetes, databases) accelerate monitoring setup.

Datadog, New Relic, and Dynatrace are commercial monitoring platforms providing infrastructure monitoring, application performance monitoring (APM), log management, and security monitoring in integrated platforms. These SaaS solutions collect metrics from agents installed on monitored systems, providing centralized visibility across large environments without managing monitoring infrastructure.

Nagios and its successors (Icinga, Zabbix) provide traditional infrastructure monitoring with check-based alerting. Rather than collecting all metrics continuously, these tools periodically check whether specific conditions are met (CPU below threshold, service responding, disk not full) and alert on failures. This approach works well for straightforward availability monitoring with lower data volume than metric-based approaches.

htop on Linux provides an enhanced interactive process viewer beyond the basic top command, with color-coded resource usage, tree view of process hierarchies, easy process management, and customizable display. glances is a comprehensive system monitoring tool that combines CPU, memory, disk, network, and process information in a single terminal display with optional web interface.

Perf (Linux) is a powerful profiling tool accessing CPU hardware performance counters, providing detailed performance analysis including cache miss rates, branch mispredictions, and instruction throughput. perf stat shows performance counter summaries for commands, perf top shows per-function CPU sampling in real time, and perf record + perf report enable detailed performance profiling of applications and system calls.

Interpreting Performance Data

Collecting performance metrics is only valuable when the data is correctly interpreted to drive actionable conclusions.

Correlation over time is the most powerful analytical technique. Performance metrics become meaningful when examined together over time—CPU spike correlating with application latency increase confirms the CPU is a bottleneck; CPU spike without latency change suggests the work is parallelizable and not user-facing. Correlating multiple metrics identifies causality versus coincidence.

Baselines make anomaly detection possible. Without knowing that normal CPU usage is 20-30%, a reading of 25% is meaningless. With a baseline, the same reading confirms normal operation, while a reading of 85% immediately flags a problem. Establishing baselines during normal operation enables pattern recognition during problems.

Saturation points identify when resources transition from adequate to bottlenecked. Most resources operate efficiently up to 70-80% utilization, then queuing theory predicts that wait times increase dramatically as utilization approaches 100%. A disk at 90% utilization may show latency 5-10x higher than at 50% utilization due to queue buildup. Knowing saturation points enables meaningful threshold alerts.

The USE method (Utilization, Saturation, Errors), developed by Brendan Gregg, provides a systematic approach to performance investigation. For every resource (CPU, memory, storage, network interfaces), examine Utilization (how busy is it?), Saturation (is there a queue waiting for it?), and Errors (are there failures?). Working through each resource systematically prevents missing bottlenecks and provides a complete picture of system health.

Distinguishing cause from symptom prevents wasted effort. High CPU usage might be caused by a legitimate increase in workload, a software bug causing infinite loops, inefficient algorithms, or security breaches (cryptocurrency mining). High I/O wait might be caused by storage hardware problems, excessive swapping due to insufficient RAM, or application patterns causing excessive reads. Metrics identify symptoms; root cause analysis determines the underlying problem.

Conclusion

System performance monitoring transforms opaque computer behavior into understandable, actionable data. By continuously measuring CPU utilization, memory consumption, storage I/O, network throughput, and application behavior, monitoring infrastructure provides the visibility needed to diagnose problems, validate optimizations, plan capacity, ensure service reliability, and understand how workloads use resources. The built-in tools in every major operating system—Task Manager and Performance Monitor on Windows, top and sar on Linux, Activity Monitor on macOS—provide immediate monitoring capability without additional software, while professional monitoring platforms extend these capabilities to enterprise scale with alerting, long-term storage, and visualization.

Effective performance monitoring is both art and science—selecting appropriate metrics for specific workloads, establishing meaningful baselines, setting alert thresholds that catch real problems without excessive false alarms, and interpreting correlated metrics to identify root causes rather than symptoms. These skills develop with experience, but the foundation is collecting comprehensive data continuously so that when problems occur, the data to diagnose them already exists. A system monitored comprehensively and continuously is a system whose problems can be understood and resolved; a system unmonitored until something breaks is a system whose problems must be diagnosed blind.

As computing evolves toward cloud-native architectures, containerized microservices, and serverless functions, performance monitoring evolves with it—adding distributed tracing, service mesh observability, and application-level metrics to traditional infrastructure monitoring. Yet the fundamental questions remain constant: what resources does this system have, how fully are they being used, are there bottlenecks, and what’s causing any performance problems? Answering these questions reliably requires the continuous, comprehensive measurement and thoughtful analysis that performance monitoring provides.

Summary Table: Performance Monitoring Tools Across Operating Systems

| Tool | Platform | Type | Key Capabilities | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task Manager | Windows | GUI, Real-time | CPU, memory, disk, network per process | Quick triage, identifying resource hogs |

| Resource Monitor | Windows | GUI, Real-time | Detailed per-process resource usage, file/network handles | Pinpointing which process uses specific resources |

| Performance Monitor | Windows | GUI, Historical | Hundreds of counters, data logging, reports | Capacity planning, long-term analysis |

| Activity Monitor | macOS | GUI, Real-time | CPU, memory, energy, disk, network per process | macOS performance triage |

| top / htop | Linux/macOS | CLI, Real-time | CPU and memory per process, system summary | Quick Linux performance overview |

| vmstat | Linux | CLI, Snapshot | CPU, memory, swap, I/O, system activity | VM and swap analysis |

| iostat | Linux | CLI, Snapshot | Per-device I/O throughput, IOPS, utilization | Storage bottleneck analysis |

| sar | Linux | CLI, Historical | CPU, memory, I/O, network over time | Historical analysis, trend identification |

| netstat / ss | Linux/macOS | CLI, Snapshot | Network connections, socket states, statistics | Network connection troubleshooting |

| perf | Linux | CLI, Profiling | Hardware counters, CPU sampling, stack traces | Low-level CPU and cache optimization |

| dstat | Linux | CLI, Real-time | Combined CPU, memory, disk, network | Unified overview in one terminal |

| Instruments | macOS | GUI, Profiling | Time profiling, memory, Core Data, custom | Application performance optimization |

| Prometheus + Grafana | Cross-platform | Server, Historical | Time-series metrics, dashboards, alerting | Cloud/server infrastructure monitoring |

| Datadog/New Relic | Cross-platform | SaaS | Infrastructure + APM, logs, alerting | Enterprise monitoring at scale |

Key Performance Metrics Reference:

| Resource | Primary Metrics | Saturation Indicators | Warning Thresholds | Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | Utilization %, run queue length, context switches | Run queue > CPU count, utilization > 80% | >80% sustained utilization | Task Manager, top, sar -u |

| Memory | Used/free/cached/swap, page faults, swap I/O | High swap I/O, major page faults, OOM events | >90% physical RAM, any swap I/O | free, vmstat, Resource Monitor |

| Disk | Throughput MB/s, IOPS, latency ms, queue depth, utilization % | Queue depth > 1, utilization > 80%, rising latency | >80% utilization, latency >10ms (HDD) / >1ms (SSD) | iostat, Resource Monitor, Activity Monitor |

| Network | Throughput Mbps, latency ms, packet loss %, errors | Throughput at interface limit, rising latency, errors | >80% interface capacity, >0.1% packet loss | netstat, sar -n, Task Manager |

| System | Load average, uptime, process count | Load > CPU count | Load > 2x CPU count | top, uptime, Task Manager |