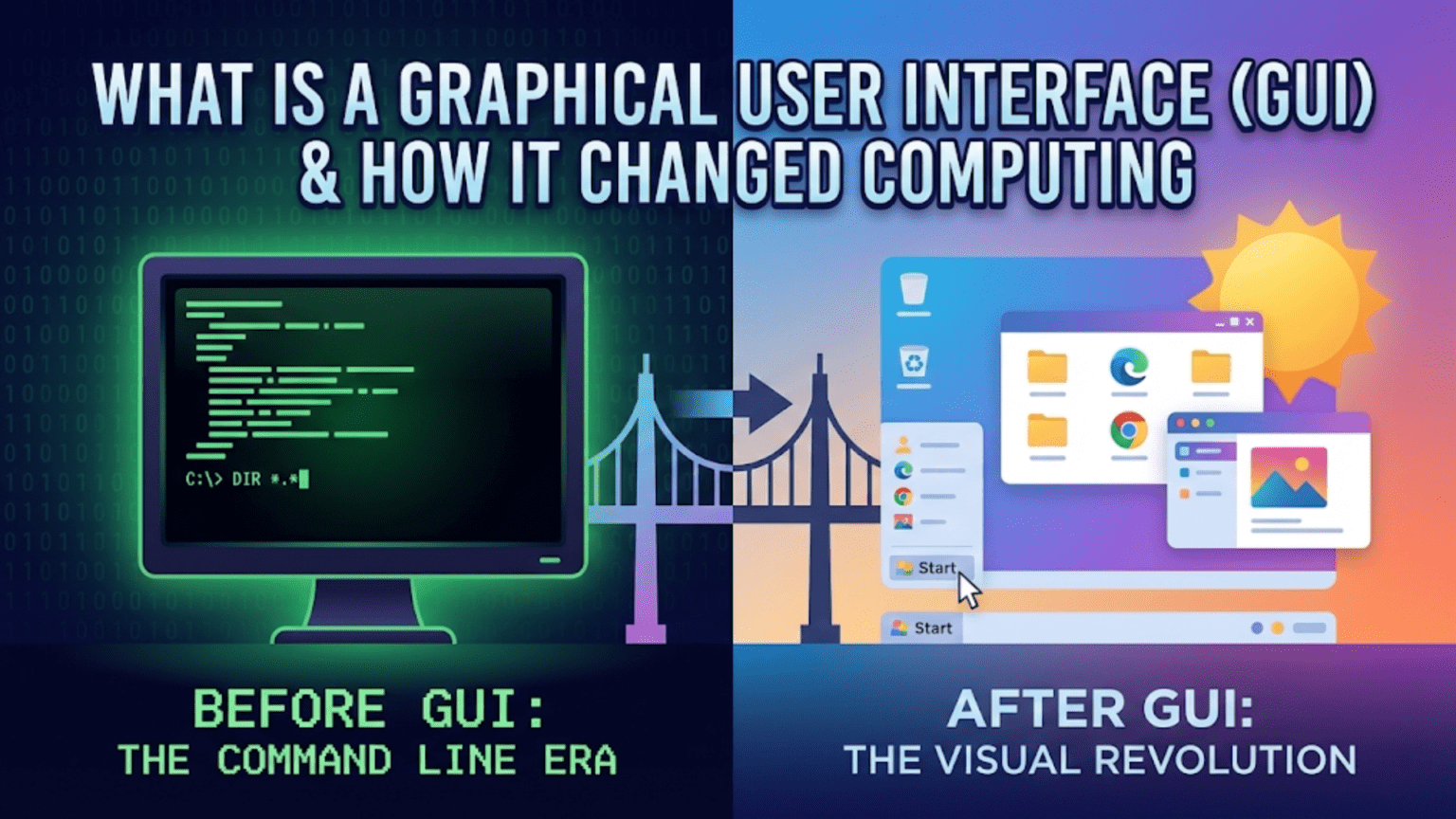

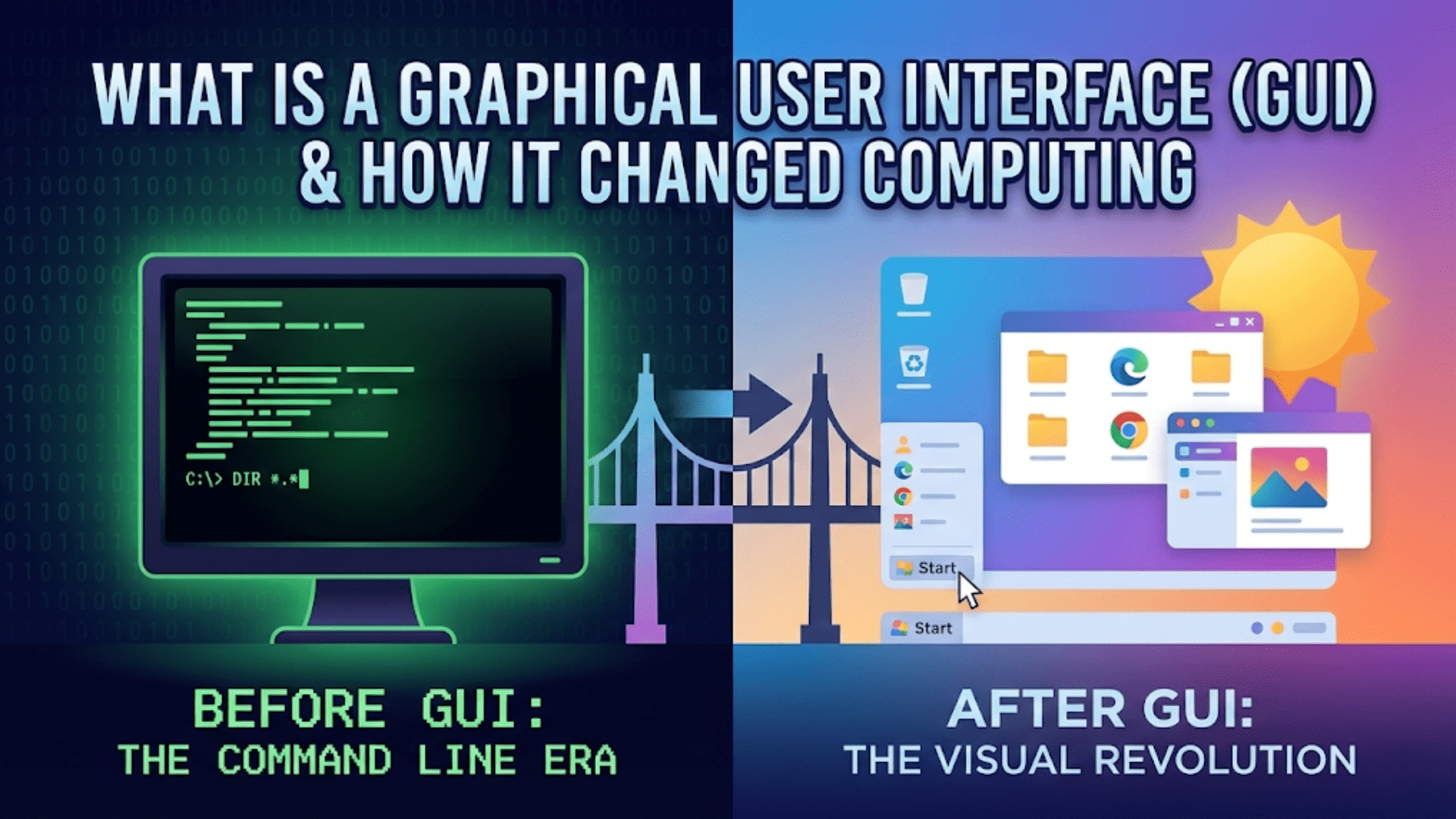

From Command Lines to Visual Computing

In the early days of personal computing, using a computer meant typing commands into a black screen filled with cryptic text. Want to see what files are on your disk? Type a command. Want to copy a file? Type another command with precise syntax, including the source path, destination path, and any options you need. Make a single typo, and the command fails with an unhelpful error message. Forget the exact command name or syntax? You’re stuck until you find the manual or remember. This was computing in the 1970s and early 1980s—powerful for those who learned the commands, but intimidating and inaccessible to the vast majority of people who might benefit from computers.

The Graphical User Interface—universally known by its acronym GUI, pronounced “gooey”—changed everything. Instead of memorizing commands, users could see visual representations of files as icons, click on them with a mouse to open them, drag them between folders to move them, and interact with programs through menus, buttons, and windows. This transformation wasn’t merely cosmetic—it fundamentally redefined who could use computers and what they could accomplish with them. The GUI democratized computing, taking it from the exclusive domain of programmers and technicians to becoming a tool that anyone could learn to use effectively.

The story of the GUI represents one of computing’s most significant innovations, involving pioneering research at Xerox PARC, commercialization by Apple, standardization by Microsoft, and continuous refinement by countless designers and developers over decades. Understanding this evolution reveals not just a technical progression but a philosophical shift in how we think about human-computer interaction. The GUI embodies the principle that computers should adapt to how humans naturally work rather than forcing humans to learn the computer’s arcane language. This human-centered approach transformed computing from a specialized technical skill into a nearly universal capability.

The Command Line: Computing Before GUIs

To appreciate the GUI’s impact, we must understand what came before. Command-line interfaces, also called text-based interfaces or CLI (Command-Line Interface), represented the standard way to interact with computers for the first several decades of computing history.

The command line presents a text prompt—a simple cursor awaiting input. Users type commands using precise syntax: the command name, followed by arguments specifying what the command should operate on, followed by options modifying the command’s behavior. The system executes the command, displays text output, and presents another prompt. This cycle continues for the entire computing session. Everything happens through text: launching programs, managing files, configuring systems, even creating and editing documents.

Command-line interfaces have genuine advantages that explain their continued use among programmers and system administrators decades after GUIs became standard. Commands can be combined in powerful ways—the output of one command can feed as input to another, creating processing pipelines that accomplish complex tasks efficiently. Scripts can automate sequences of commands, running them unattended or on schedules. For repetitive tasks or batch operations affecting many files, command-line operations can be far faster than clicking through graphical interfaces. Remote system administration over slow network connections works better with text commands than with graphics-heavy GUIs.

However, command lines also present significant challenges. Learning requires memorizing numerous commands, their syntax, and their options—a substantial initial investment. Small errors in syntax cause commands to fail, often with cryptic error messages that don’t clearly explain what went wrong. Discovering available commands and their capabilities requires consulting documentation since the interface provides no visual hints. For users performing occasional tasks rather than daily administrative work, remembering infrequently used commands becomes difficult. The cognitive load is high—you must hold command syntax in memory while also thinking about what you want to accomplish.

Different command-line systems use different command sets and syntax. Unix and Linux use one set of commands, DOS and Windows use another, and various other systems use their own conventions. While commonalities exist, someone who learns Linux commands must still learn different commands for Windows. This fragmentation increased the barrier to entry—mastering one system didn’t automatically transfer to others.

The fundamental problem with command lines is that they require users to know what’s possible before they can do it. You can’t browse available commands the way you can browse menu options in a GUI. You can’t discover features by exploring—you need documentation or someone to teach you. This opacity made computing inaccessible to casual users who just wanted to accomplish specific tasks without becoming computer experts.

The Birth of the GUI: Xerox PARC and the Alto

The graphical user interface didn’t appear fully formed—it evolved through years of research, experimentation, and refinement. The story begins in the early 1970s at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox PARC), one of the most influential research laboratories in computing history.

Researchers at Xerox PARC were exploring how to make computing more accessible and productive. They drew inspiration from Douglas Engelbart’s 1968 demonstration of revolutionary interface concepts including the mouse, hypertext, and video conferencing. Engelbart’s “Mother of All Demos” showed possibilities that inspired a generation of interface designers. Xerox PARC set out to refine and extend these concepts into a complete computing environment.

The result was the Xerox Alto, first operational in 1973. The Alto featured a high-resolution display capable of showing crisp text and graphics, a mouse pointing device for direct manipulation of on-screen objects, networking capabilities allowing collaboration between machines, and most importantly, a graphical interface that pioneered concepts we now take for granted. The Alto displayed overlapping windows that could be moved and resized, icons representing files and programs, menus listing available commands, and a desktop metaphor that presented the screen as a virtual desk where documents could be arranged.

The desktop metaphor became foundational to GUI design. By presenting the computer in terms of familiar real-world objects—desks, files, folders, documents, trash cans—the interface leveraged existing knowledge. Users didn’t need to learn entirely new concepts; they could transfer understanding from their physical desk to the virtual one. Want to throw away a file? Drag it to the trash can, just like discarding a paper document. Want to organize related files? Put them in a folder, just like physical documents. This metaphorical approach made computing more intuitive by building on existing mental models.

WYSIWYG—”What You See Is What You Get”—became possible with graphical displays. On the Alto, documents on screen looked the same as they would when printed. Users could see exactly how text would be formatted, where graphics would appear, and how pages would lay out. This direct connection between screen representation and final output eliminated the mental translation required by command-line text editors where you typed formatting codes and had to imagine the final appearance.

Xerox developed several groundbreaking applications for the Alto, including Bravo (a word processor with WYSIWYG editing), Draw (a drawing program), and the first graphical email client. These applications demonstrated how GUIs enabled new types of software that would be impossible or impractical with command-line interfaces. However, Xerox, primarily a copier company, failed to commercialize the Alto effectively. The system was expensive, limited to internal use and research institutions, and never reached consumer markets despite its revolutionary interface.

Apple’s Popularization: Lisa and Macintosh

The GUI might have remained a research curiosity if not for Apple’s recognition of its potential. Steve Jobs famously visited Xerox PARC in 1979, seeing the Alto and immediately understanding its significance. Apple set out to bring graphical computing to mainstream users, first with the Lisa in 1983 and then with the Macintosh in 1984.

The Lisa featured a sophisticated GUI with overlapping windows, pull-down menus, icons, and dialog boxes. It implemented concepts that became standard: clicking to select objects, double-clicking to open items, dragging to move things, menu bars at the top of windows, dialog boxes for settings, and alert boxes for errors. The Lisa was technically impressive but commercially unsuccessful due to its high price—nearly $10,000, far beyond what most users could afford.

The Macintosh, released in 1984 at $2,495, made graphical computing affordable for far more users. The Mac simplified the Lisa’s interface while retaining its essential concepts. The famous “1984” Super Bowl commercial positioning the Mac as liberating computing from conformity captured the revolutionary nature of accessible GUI computing. The Macintosh demonstrated that graphical interfaces could work on relatively affordable hardware, making the GUI’s benefits available beyond research labs and corporate buyers.

Apple established interface guidelines that ensured consistency across applications. The Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines specified how menus should work, what keyboard shortcuts to use for common operations, how dialog boxes should be structured, and countless other details. This consistency meant that once users learned to use one Mac application, they largely knew how to use others. Common operations worked the same way everywhere, dramatically reducing the learning curve for new software.

The Macintosh proved that GUIs weren’t just theoretically better interfaces—they enabled entirely new classes of users to be productive with computers. People who would never learn command-line computing could use a Mac effectively after modest training. Desktop publishing became possible, combining WYSIWYG word processing and page layout with PostScript printers. Graphic design, previously requiring specialized equipment, became accessible through programs like MacPaint. The GUI didn’t just make existing tasks easier; it enabled new possibilities.

Microsoft Windows and GUI Standardization

While Apple popularized the GUI, Microsoft brought it to the IBM PC-compatible platform, where its impact became even more widespread due to the PC’s market dominance.

Microsoft Windows evolved through several generations before achieving mainstream success. Windows 1.0 (1985) and 2.0 (1987) were primitive GUI shells running on top of DOS, offering tiled windows and basic graphical interfaces but lacking the sophistication of the Macintosh. Windows 3.0 (1990) and especially Windows 3.1 (1992) achieved much better usability and performance, becoming genuinely popular and establishing Windows as the dominant GUI platform.

Windows 95, released in 1995, represented a massive leap forward and established interface conventions that persist today. It introduced the Start menu—a single location for accessing all programs and system functions. The taskbar showed running programs and system notifications. The desktop became the primary organizational space. Right-clicking provided context menus with object-specific options. These innovations made Windows more intuitive and discoverable than previous versions, helping millions of users transition from command-line DOS to graphical computing.

Microsoft, like Apple, published extensive interface guidelines ensuring consistency across Windows applications. Windows applications followed common patterns: File menus with New/Open/Save/Print options, Edit menus with Cut/Copy/Paste, standard keyboard shortcuts like Ctrl+C for copy and Ctrl+V for paste, and consistent dialog boxes. This standardization meant users developed transferable skills—learning one Windows program helped with learning others.

The widespread adoption of Windows established the GUI as the standard interface for personal computing. By the late 1990s, command-line interfaces had largely disappeared from typical user interactions. Computers shipped with graphical operating systems pre-installed. Software assumed graphical displays and mouse input. The GUI transition was complete—computing had become visual.

Core GUI Concepts and Components

Modern GUIs, whether on computers, phones, or tablets, share common elements and interaction patterns that users understand intuitively. These components form the vocabulary of graphical interfaces.

Windows are rectangular areas displaying application content. They can be moved, resized, minimized to the taskbar, maximized to fill the screen, or closed entirely. Multiple windows can exist simultaneously, either tiled edge-to-edge or overlapping. The window management system handles keeping track of which window is active, managing overlap drawing, and coordinating input to the correct window.

Icons are small graphical representations of files, folders, or programs. They provide visual identification—you recognize a document by its icon rather than reading a filename. Different file types have distinct icons indicating what they contain. Icons can typically be arranged, sorted, and organized in various views, from large graphical displays to compact lists showing additional information.

Menus organize commands hierarchically. Menu bars typically sit at the top of windows or the screen, with menu titles like File, Edit, View, and Help. Clicking a menu title reveals a dropdown list of related commands. Submenus provide additional organization for complex applications. Context menus, accessed by right-clicking objects, show commands relevant to that specific item, making features discoverable.

Buttons trigger actions when clicked. They’re clearly labeled with text and sometimes icons indicating what they do. Common buttons include OK, Cancel, Apply, and various action-specific options. Visual feedback—buttons appearing to depress when clicked—confirms the interaction occurred.

Dialog boxes present information or request input. Modal dialogs block interaction with the main application until addressed, focusing attention on the dialog’s purpose. Non-modal dialogs allow continued work while the dialog remains visible. Dialogs combine multiple interface elements—text fields, checkboxes, dropdown lists, buttons—to accomplish their purpose efficiently.

Scrollbars enable navigation through content larger than the available display area. Clicking arrows scrolls small amounts, clicking the track scrolls by pages, or dragging the thumb provides direct navigation. The scrollbar’s proportions indicate how much content exists relative to the visible portion, providing context about your position in the document.

Text fields accept keyboard input for entering data. They provide visual feedback showing the current input, a cursor indicating position, and selection highlighting. Modern text fields often include features like autocomplete, spell-checking, and input validation, enhancing usability beyond simple text entry.

Checkboxes and radio buttons provide ways to select options. Checkboxes allow multiple independent selections—each can be checked or unchecked separately. Radio buttons represent mutually exclusive choices—selecting one automatically deselects others in the group. These controls make selection obvious and unambiguous.

Sliders offer intuitive adjustment of values by dragging a handle along a track. They’re particularly effective for settings where the exact numeric value matters less than the relative position, like volume or brightness controls.

Toolbars collect frequently used commands as icon buttons, providing quick access without navigating menus. They often include tooltips—small text descriptions appearing when hovering over buttons—that explain each tool’s purpose.

The Psychology of Effective GUIs

Good GUI design isn’t just about aesthetics—it’s grounded in understanding how humans perceive information and interact with systems. Effective interfaces leverage psychological principles to enhance usability.

Direct manipulation creates a sense of control by letting users interact directly with objects rather than through abstract commands. Dragging a file to move it feels more natural than typing a command specifying source and destination paths. This directness reduces cognitive load—users can focus on their goal rather than remembering command syntax.

Visual affordances—design cues suggesting how objects can be used—make interfaces more discoverable. Buttons look clickable through shading and borders. Sliders look draggable. Text fields look like places to type. These visual cues help users understand what’s possible without explicit instruction.

Consistency reduces learning requirements by applying the same patterns throughout the interface. Once you learn that Ctrl+C copies text in one application, you expect it to work the same way everywhere. This consistency enables skill transfer between applications and reduces the cognitive burden of learning new software.

Feedback confirms that actions have been received and are being processed. Buttons depress when clicked. Cursors change shape when hovering over different elements. Progress bars show lengthy operations advancing. Without feedback, users feel uncertain whether their actions registered and may click repeatedly, causing problems.

Recognition rather than recall reduces memory demands. Menus list available commands rather than requiring users to remember them. Dialog boxes present options rather than expecting users to know what values are valid. Graphical representations help users recognize files and folders they’re looking for rather than recalling exact names.

Error prevention and recovery help users avoid mistakes and correct them easily. Confirmation dialogs prevent accidental destructive actions. Undo capabilities let users reverse mistakes. Clear error messages explain what went wrong and how to fix it. These features acknowledge that humans make mistakes and design for graceful handling rather than assuming perfection.

Progressive disclosure shows information in stages, presenting the most common options prominently while hiding advanced features until needed. This approach serves both novice users (who aren’t overwhelmed by complexity) and experts (who can access advanced features when wanted). Expanding sections, tabbed dialogs, and advanced settings areas implement progressive disclosure.

GUIs Beyond the Desktop: Mobile and Touch

The smartphone revolution required rethinking GUI principles for touch interfaces without mice or keyboards. Mobile GUIs adapted desktop concepts while introducing new interaction patterns specific to touch.

Touch targets must be larger than desktop interface elements because fingers are less precise than mouse pointers. Buttons and controls need sufficient size and spacing to prevent accidental activation of adjacent items. Mobile interfaces use larger touch targets than desktop interfaces, sacrificing information density for usability.

Gestures extend beyond clicking, leveraging touch capabilities. Swiping scrolls or switches between items. Pinching zooms. Long-pressing reveals context menus. Two-finger gestures perform specialized actions. These gestures feel natural because they mimic physical interactions—pinching to zoom is like stretching or compressing physical objects.

Mobile interfaces favor full-screen applications rather than windows. The limited screen space makes window management impractical, so applications typically take the full screen, with switching between apps replacing window management. This simplification reduces complexity at the cost of multitasking convenience.

Mobile navigation emphasizes hierarchical structures and clear paths back to previous screens. Back buttons or swipe gestures allow retracing steps through the interface. Tab bars and navigation bars provide primary navigation between major sections. These patterns help users maintain orientation in complex applications on small screens.

Virtual keyboards replace physical keyboards, appearing when text input is needed and disappearing when not needed to maximize screen space for content. Autocorrect, predictive text, and other assistive features compensate for touch typing’s reduced accuracy.

Responsive design adjusts interfaces to different screen sizes and orientations, ensuring usability across phones, tablets, and various display configurations. Layouts reflow, controls resize, and navigation adapts to available space, maintaining usability across diverse devices.

The Command Line’s Persistence

Despite the GUI’s dominance, command-line interfaces persist and even thrive in specific contexts. Understanding where and why CLIs remain relevant provides perspective on interface trade-offs.

System administration and automation still heavily rely on command lines. Administrators managing dozens or hundreds of servers need scriptable, automatable interfaces. GUIs work well for one-off tasks but become tedious for repetitive operations. Scripts can perform complex operations unattended, execute on schedules, and respond to events—capabilities difficult or impossible with GUIs.

Development and programming environments often feature prominent command-line components. Version control systems like Git, build systems, package managers, and deployment tools commonly use command-line interfaces. Developers appreciate the precision, scriptability, and efficiency of commands for these technical tasks.

Remote administration over limited bandwidth connections works better with text commands than graphics. Transmitting text requires minimal data compared to graphical displays. Command-line SSH sessions work reliably over slow or intermittent connections where graphical remote desktop would be unusable.

Power users often prefer command lines for specific tasks because they can be faster once learned. A complex file operation might require dozens of clicks through multiple graphical dialogs but could be expressed as a single command line. For users who have invested in learning commands, the CLI provides efficiency that GUIs struggle to match.

Modern development has seen a resurgence of command-line tools, particularly in web development. Node.js, Python, Ruby, and other ecosystems use command-line tools for package management, testing, building, and deployment. These tools prioritize scriptability and integration with development workflows over graphical simplicity.

The ideal modern system combines both paradigms—GUIs for approachability and discoverability, CLIs for power and automation. Operating systems typically provide both, letting users choose the interface appropriate for each task. Understanding both interface types, their strengths, and their appropriate use cases makes users more effective across different computing contexts.

GUI Design Principles for Modern Interfaces

Decades of GUI evolution have established design principles that guide interface development. These principles help create interfaces that are intuitive, efficient, and satisfying to use.

Simplicity prioritizes essential features and minimizes clutter. Every interface element should serve a purpose. Removing unnecessary elements improves focus and reduces cognitive load. Simplicity doesn’t mean limiting functionality—it means presenting power without overwhelming complexity.

Clarity ensures users understand what they’re seeing and what actions are available. Labels should be descriptive, icons should be recognizable, and the purpose of interface elements should be obvious. Ambiguity causes confusion and errors.

Hierarchy organizes information by importance. The most important elements—primary actions, key information—should be most prominent. Visual weight, size, position, and color establish hierarchy, guiding users’ attention to what matters most.

Accessibility ensures interfaces work for users with diverse abilities. This includes supporting keyboard navigation for users who can’t use mice, providing sufficient color contrast for users with visual impairments, including screen reader support for blind users, and accommodating users with motor impairments through appropriately sized controls and forgiving interaction models.

Performance matters—interfaces should respond quickly to user input. Sluggish interfaces frustrate users and create doubt about whether actions registered. Even when operations take time, immediate feedback that the system received the input maintains user confidence.

Aesthetics contribute to usability by making interfaces pleasant to use and establishing visual hierarchy through thoughtful design. Beautiful interfaces aren’t just superficial polish—they encourage engagement and communicate quality and attention to detail.

The Future of Graphical Interfaces

GUI technology continues evolving, with new interaction paradigms and display technologies suggesting future directions.

Voice interfaces increasingly handle tasks traditionally requiring graphical interaction. Digital assistants can set reminders, search information, control smart home devices, and perform other tasks through spoken commands. Voice provides hands-free interaction valuable while driving, cooking, or otherwise occupied.

Gesture control without physical touch enables interaction through hand movements recognized by cameras. Gaming systems pioneered this, and it’s expanding to other contexts where touchless control is valuable—medical settings where maintaining sterility matters, or public displays where hygiene concerns make touch undesirable.

Augmented reality overlays graphical information on the physical world through headsets or smartphone cameras. AR interfaces blend digital and physical, enabling new interaction patterns where virtual objects coexist with real ones. Applications range from navigation and training to entertainment and design visualization.

Virtual reality creates fully immersive graphical environments. VR interfaces abandon the desktop metaphor entirely, implementing interfaces in three-dimensional space where users move naturally. While still niche, VR demonstrates that GUIs need not be constrained to flat screens.

Adaptive interfaces adjust to user behavior, skill level, and context. Machine learning enables interfaces that customize themselves—showing frequently used commands prominently, hiding rarely used features, and optimizing layouts for individual preferences. These intelligent interfaces promise reduced learning curves and improved efficiency.

Brain-computer interfaces represent the ultimate direct interaction, detecting neural signals and translating them to commands. While currently limited and experimental, BCIs suggest a future where thought directly controls interfaces, eliminating physical interaction entirely.

The GUI’s Enduring Impact

The graphical user interface transformed computing from an esoteric technical discipline to a nearly universal tool accessible to billions. It enabled creativity through desktop publishing and digital art. It made information accessible through the World Wide Web. It put computing power in pockets through smartphones. None of this would have been possible with command-line interfaces demanding specialized knowledge.

The GUI succeeded not through technical superiority alone but by acknowledging human capabilities and limitations. It leveraged visual perception, spatial reasoning, and manual dexterity—human strengths. It reduced memory demands, forgave mistakes, and provided discovery mechanisms—accommodating human limitations. This human-centered approach represents a profound shift in how we design technology, prioritizing users’ needs over technical convenience.

Understanding the GUI’s history and principles provides perspective on interface design and appreciation for the thoughtful engineering behind seemingly simple interactions. When you double-click an icon, drag a file to a folder, or select text with your mouse, you’re using interaction patterns refined over decades of research and development. These patterns feel natural because they’ve been designed to align with human cognition, making the computer an extension of human capability rather than an obstacle to overcome.

The next time you use your computer, smartphone, or tablet, consider the invisible sophistication enabling your interactions. The icons you click, the windows you resize, the menus you navigate—each represents careful design decisions and technical implementation that collectively create the illusion of direct manipulation. The GUI made computing accessible to the world, and its principles continue guiding interface development as we explore new interaction paradigms for emerging technologies.