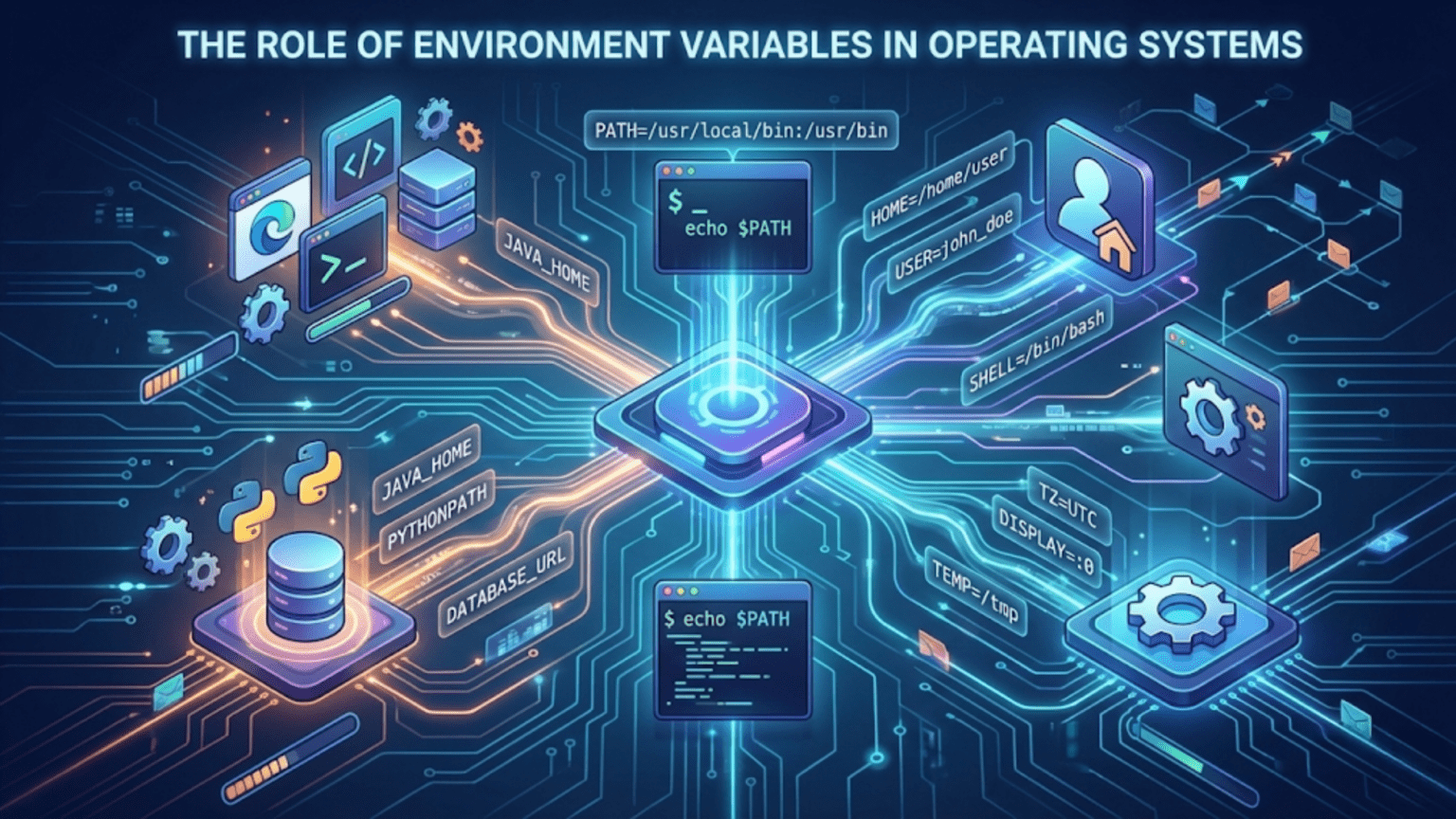

Environment variables are dynamic named values stored by the operating system that affect how running processes and applications behave. They provide a way to pass configuration information to programs, specify system paths, define user preferences, and control application behavior without hardcoding values, making software more flexible and portable across different systems and configurations.

When you open a command prompt and type a program name without specifying its full path, your computer somehow knows where to find and execute that program. When applications need to create temporary files, they know exactly where to store them. When software needs to identify who is currently using the computer, it has access to that information instantly. All of these capabilities and countless others rely on environment variables—invisible configuration values that operating systems maintain to provide essential information to programs and system components. Environment variables represent one of the most fundamental mechanisms through which operating systems communicate configuration and context to the software running on them, creating a flexible, portable way to manage system-wide and user-specific settings.

Environment variables serve as a universal language that operating systems use to share information with applications and shell sessions. Rather than forcing every program to search for configuration files, hardcode system paths, or implement custom methods to discover system information, operating systems provide a standardized set of named variables that any program can query. This standardization enables software portability—a program can check the TEMP environment variable to find the appropriate temporary file location rather than guessing different paths for different operating systems. It allows system administrators to configure software behavior across multiple machines by setting variables consistently. It provides users with customization capabilities without editing application code. Understanding environment variables reveals how operating systems provide context and configuration to the software ecosystem, enabling the smooth interaction between system and applications that modern computing depends upon.

What Environment Variables Are and Why They Exist

Environment variables are key-value pairs maintained by the operating system, where each variable has a name (the key) and an associated value (typically a text string). The operating system stores these variables in memory and makes them available to all running processes, which can read the variables to obtain information about the system environment.

At the most basic level, an environment variable consists of a name that identifies the variable and a value that contains the actual data. For example, a variable named “USERNAME” might have the value “John” indicating the current user’s name, while a variable named “TEMP” might contain “C:\Users\John\AppData\Local\Temp” specifying where to store temporary files. Programs access these variables through standardized operating system APIs, requesting variables by name and receiving their values.

Environment variables exist to solve several fundamental problems in operating system and application design. They provide abstraction from system-specific details—instead of a program needing to know that temporary files go in /tmp on Linux but C:\Temp on Windows, it can simply query the TEMP or TMP variable, which the operating system sets appropriately for that platform. This abstraction makes software more portable across different systems.

They enable configuration without code modification. System administrators can change how applications behave by modifying environment variables rather than recompiling programs or editing application code. A database connection string, server URL, or feature flag can be set through environment variables, allowing the same program binary to work in development, testing, and production environments with different configurations simply by setting different variable values.

Environment variables provide context to processes. When a program starts, it needs information about its execution environment—who is running it, what directory it started from, where system tools are located, what capabilities the system has. Environment variables deliver this contextual information automatically, without programs needing to query multiple system APIs or configuration files.

They support inheritance and scope. When a process creates a child process (like when you run a program from a shell), the child inherits the parent’s environment variables by default. This inheritance means settings propagate naturally through process trees, so programs launched from a configured environment automatically receive that configuration. However, variables can also be scoped differently—some might be system-wide (affecting all processes), some user-specific (affecting one user’s processes), and some process-specific (affecting only one program and its children).

The concept of environment variables originated in early Unix systems in the 1970s as a mechanism for the shell to pass information to programs it executed. The Unix shell maintained a set of named variables, and when it launched a program, it provided that program with a copy of these variables. This simple but powerful concept proved so useful that virtually all modern operating systems implement environment variables, though the specific variables available and mechanisms for managing them vary across platforms.

Environment variables fill a niche between permanent configuration (stored in files or databases) and command-line arguments (passed when launching programs). Configuration files are appropriate for complex, structured settings but require programs to know where to find them. Command-line arguments are good for per-invocation options but become unwieldy for settings that should apply to all invocations or many programs. Environment variables provide middle-ground configuration that persists across program invocations, applies to multiple programs, and can be easily modified without editing files or changing how you launch programs.

Common Environment Variables and Their Purposes

Operating systems define standard environment variables that provide essential system information and configuration, with some variables common across all platforms and others specific to particular operating systems.

The PATH variable is arguably the most important environment variable on any operating system. It contains a list of directory paths (separated by semicolons on Windows, colons on Unix-like systems) where the operating system searches for executable programs. When you type a command like “python” or “git” without specifying the full path to the executable, the shell searches each directory listed in PATH until it finds a matching executable. Without PATH, you would need to type the complete path for every command, like “/usr/bin/python” instead of just “python”. System administrators modify PATH to make custom software accessible from anywhere, and software installers often add their installation directories to PATH automatically.

The HOME variable (on Unix-like systems) or USERPROFILE (on Windows) specifies the current user’s home directory. This is where user-specific files, configurations, and data are stored. Applications use this variable to locate user preferences files, default save locations, and other user-specific data. When a program needs to store settings per-user rather than system-wide, it typically creates files or directories within the home directory referenced by this variable.

TEMP and TMP variables specify the directory for temporary files. Applications that need to create temporary files for processing—like when extracting compressed archives, compiling programs, or processing large datasets—use these variables to determine where to place temporary data. The operating system or user can change these variables to redirect temporary files to locations with more disk space, faster storage, or appropriate cleanup policies.

The USER or USERNAME variable identifies the currently logged-in user. Programs can reference this to personalize behavior, create user-specific log files, or enforce user-based permissions. The value typically matches the login name used to authenticate to the system.

SHELL (on Unix-like systems) indicates which command-line shell the user prefers—bash, zsh, fish, etc. Programs that need to execute shell commands or provide shell integration consult this variable to use the correct shell. On Windows, ComSpec serves a similar purpose, pointing to the command interpreter (typically cmd.exe).

LANG, LANGUAGE, and LC_* variables control localization and internationalization on Unix-like systems. They determine which language applications display messages in, what character encoding to use, how dates and numbers are formatted, and other locale-specific behaviors. An application can check these variables to automatically display in the user’s preferred language without requiring explicit language selection.

The EDITOR variable on Unix-like systems specifies the user’s preferred text editor. Command-line tools that need to open a text editor (like git for commit messages or crontab for editing scheduled tasks) use this variable to determine which editor to launch. Users might set this to “vim”, “nano”, “emacs”, or their preferred editor.

OS or OSTYPE variables identify the operating system type, helping scripts and programs adapt their behavior to different platforms. A script might check these variables to use platform-specific commands or file paths.

SYSTEMROOT and WINDIR on Windows point to the Windows installation directory (typically C:\Windows). System tools and applications use these variables to locate Windows components, system libraries, and configuration files regardless of where Windows is actually installed.

APPDATA, LOCALAPPDATA, and PROGRAMDATA on Windows specify directories for application data. APPDATA points to roaming application data (synchronized across machines in domain environments), LOCALAPPDATA points to machine-specific application data, and PROGRAMDATA is for application data shared by all users on the machine. Applications use these variables to store settings, cache data, and other application-specific files in the appropriate locations according to Windows design guidelines.

DISPLAY on Unix-like systems (particularly with X11 or Wayland graphics) indicates which graphical display to use for GUI applications. This variable becomes important when running programs remotely via SSH with X forwarding or when multiple graphical sessions exist on the same machine.

Java and other runtime environments often define their own variables. JAVA_HOME points to the Java Development Kit installation directory, allowing build tools and IDEs to locate Java executables and libraries. Similarly, PYTHON_HOME, NODE_PATH, and other language-specific variables help tools and applications locate runtime environments and libraries.

Development-related variables like DEBUG, NODE_ENV, or ENVIRONMENT help applications switch between development, testing, and production modes. Setting NODE_ENV=production in Node.js applications, for example, enables performance optimizations and disables verbose logging.

How Different Operating Systems Manage Environment Variables

While the concept of environment variables is universal across operating systems, the mechanisms for viewing, setting, and managing them differ significantly between Windows, macOS, Linux, and other platforms.

Windows manages environment variables at two levels: system-wide (affecting all users) and user-specific (affecting only one user). System environment variables are stored in the Windows Registry under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Session Manager\Environment, while user-specific variables are stored under HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Environment in each user’s Registry hive. When a process starts, Windows constructs its environment by first copying system variables and then overlaying user variables, with user variables taking precedence if names conflict.

You can view and modify Windows environment variables through several interfaces. The System Properties dialog (accessible via “Advanced system settings” from the System control panel or by running “sysdm.cpl”) provides a graphical interface showing both system and user variables with buttons to add, edit, or delete variables. This interface is the most common way users modify environment variables on Windows.

From the Windows Command Prompt, you can view all environment variables by typing “set” without arguments, which displays the current environment. Setting a variable temporarily (for the current session only) is done with “set VARIABLE_NAME=value”. To view a specific variable, use “echo %VARIABLE_NAME%” with the variable name wrapped in percent signs. PowerShell uses different syntax: “Get-ChildItem Env:” lists all variables, “$env:VARIABLE_NAME” accesses a variable’s value, and “$env:VARIABLE_NAME = ‘value'” sets a variable temporarily.

Making permanent environment variable changes on Windows requires either using the System Properties GUI or modifying the Registry directly (though the GUI is safer and recommended). Command-line tools can make permanent changes through “setx VARIABLE_NAME value” which writes to the Registry, though setx has limitations and quirks that make the GUI preferable for most users.

On Linux and Unix-like systems (including macOS), environment variables are managed primarily through shell configuration files. Different shells (bash, zsh, fish, etc.) use different files, but the concept is similar: configuration files executed when shells start contain commands that set environment variables for that shell session and any programs launched from it.

For bash on Linux, system-wide environment variables are typically set in /etc/environment (a simple file of NAME=value pairs) or in scripts within /etc/pro.file.d/ that execute during shell startup. User-specific variables are commonly set in ~/.ba.shrc (for interactive non-login shells), ~/.ba.sh_profile or ~/.profile (for login shells), or ~/.ba.sh_login. The distinction between login and non-login shells affects which files execute, and understanding this helps ensure variables are set correctly.

On macOS, which uses zsh as the default shell in recent versions, the primary configuration files are /etc/zshenv, /etc/zprofile, ~/.zshenv, and ~/.zprofile. System-wide variables can be set in /etc/paths (a file containing directory paths to add to PATH, one per line) or through launchd configuration for graphical applications.

Viewing and setting variables in Unix shells uses straightforward syntax. Typing “printenv” or “env” displays all current environment variables. To view a specific variable, use “echo $VARIABLE_NAME” with a dollar sign prefix. Setting a variable temporarily (for the current shell session) uses “VARIABLE_NAME=value” in bash/zsh. To export a variable so child processes inherit it, use “export VARIABLE_NAME=value” or “VARIABLE_NAME=value” followed by “export VARIABLE_NAME” on a separate line.

Making permanent changes requires editing the appropriate configuration file. Adding “export VARIABLE_NAME=value” to ~/.ba.shrc or ~/.zs.hrc sets the variable every time you open a new shell. After editing these files, you need to either restart your shell or “source” the file (run “. ~/.ba.shrc” or “source ~/.ba.shrc”) to apply changes to the current session.

The PATH variable receives special treatment on most systems due to its importance. On Windows, the System Properties dialog provides dedicated interfaces for editing PATH, showing it as a list rather than a single string. On Unix-like systems, PATH is typically modified by appending or prepending to its existing value: “export PATH=/new/directory:PATH”addsadirectorytothefrontofPATH(givingitpriority),while”exportPATH=PATH:/new/directory” adds it to the end.

macOS has additional complexity because environment variables set in shell configuration files aren’t automatically available to graphical applications launched from the Dock or Spotlight. Historically, this required setting variables in special files like ~/.MacOSX/environment.plist or using launchd configuration. Recent macOS versions have simplified this somewhat, but ensuring environment variables are available to both terminal and GUI applications can still require multiple configuration locations.

Environment Variables in Different Programming Languages

Programming languages and runtime environments provide various mechanisms for accessing and manipulating environment variables, making them available to application code.

In C and C++, the standard library provides functions for environment variable access. The getenv() function retrieves a variable’s value by name, returning a pointer to the value string or NULL if the variable doesn’t exist. For example, “char *home = getenv(“HOME”);” retrieves the HOME variable. Setting variables uses putenv() or setenv(), though these functions only affect the current process’s environment, not the system-wide or persistent environment. The global variable “extern char **environ” points to an array of all environment variables in “NAME=VALUE” format, allowing programs to iterate through the entire environment.

Python offers the os.environ dictionary for environment variable access. Reading a variable is as simple as “value = os.environ[‘VARIABLE_NAME’]” or using os.environ.get(‘VARIABLE_NAME’, ‘default’) to provide a default value if the variable doesn’t exist. Setting variables uses “os.environ[‘VARIABLE_NAME’] = ‘value'”, and deleting variables uses “del os.environ[‘VARIABLE_NAME’]”. The os.getenv() function provides a more functional interface: “value = os.getenv(‘VARIABLE_NAME’, ‘default’)”. Changes to os.environ affect the current Python process and any child processes it creates but don’t persist beyond the program’s execution or affect other processes.

Java accesses environment variables through System.getenv(). Calling System.getenv(“VARIABLE_NAME”) returns the variable’s value as a String, or null if it doesn’t exist. System.getenv() without arguments returns a Map<String, String> containing all environment variables. Java doesn’t provide a standard way to set environment variables (as this is considered poor practice in Java applications), though some third-party libraries enable it through native code. The recommended approach in Java is to use system properties (set with -D flags) rather than environment variables for application configuration.

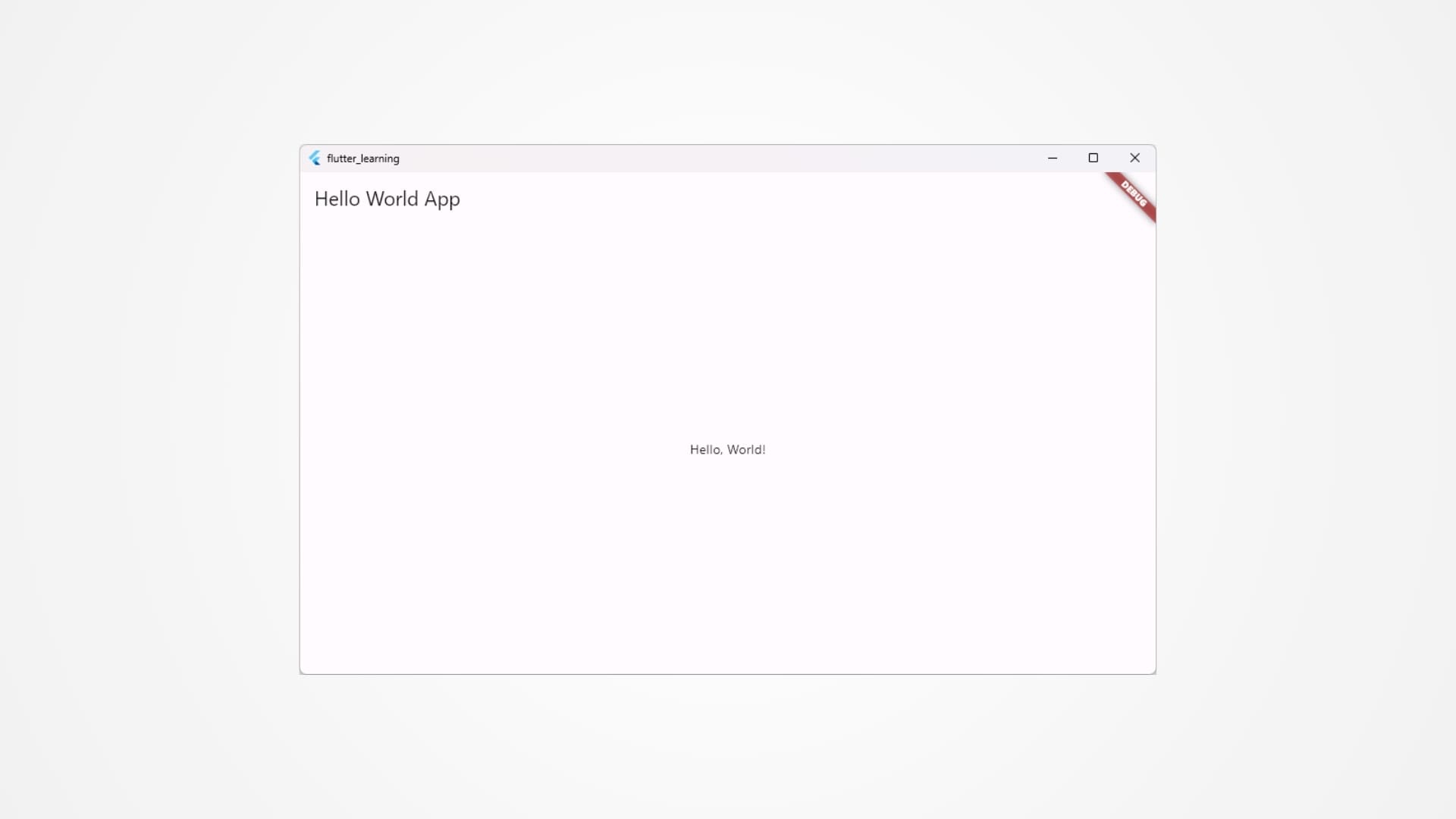

JavaScript in Node.js accesses environment variables through process.env, an object containing all environment variables as properties. Reading is straightforward: “const value = process.env.VARIABLE_NAME”. Setting variables uses simple assignment: “process.env.VARIABLE_NAME = ‘value'”, affecting the Node.js process and any child processes. The popular dotenv package allows Node.js applications to load environment variables from .env files, making it easy to manage different configurations for development and production.

Shell scripting languages (bash, zsh, PowerShell) work directly with environment variables as core language features. In bash/zsh, variables are accessed with $VARIABLE_NAME, set with VARIABLE_NAME=value, and exported with “export VARIABLE_NAME” to make them available to child processes. PowerShell uses $env:VARIABLE_NAME to access variables and “$env:VARIABLE_NAME = ‘value'” to set them. These shells make environment variable manipulation central to their operation since shell scripts often serve as glue coordinating multiple programs that communicate through environment variables.

Ruby provides ENV, a hash-like object for environment variable access. Reading uses “ENV[‘VARIABLE_NAME’]” or ENV.fetch(‘VARIABLE_NAME’, ‘default’), setting uses “ENV[‘VARIABLE_NAME’] = ‘value'”, and deletion uses “ENV.delete(‘VARIABLE_NAME’)”. Ruby’s ENV object provides typical hash operations like iteration, making it easy to work with the entire environment.

Go (Golang) offers os.Getenv(“VARIABLE_NAME”) to retrieve variables, returning an empty string if the variable doesn’t exist. For distinguishing between empty values and missing variables, os.LookupEnv(“VARIABLE_NAME”) returns both the value and a boolean indicating whether the variable exists. Setting variables uses os.Setenv(“VARIABLE_NAME”, “value”), and unsetting uses os.Unsetenv(“VARIABLE_NAME”). The os.Environ() function returns a slice of all environment variables in “NAME=VALUE” format.

Rust accesses environment variables through the std::env module. The env::var(“VARIABLE_NAME”) function returns a Result type—Ok containing the value if successful, or Err if the variable doesn’t exist or contains invalid Unicode. The env::var_os(“VARIABLE_NAME”) variant returns an OsString, handling non-Unicode values gracefully. Setting variables uses env::set_var(“VARIABLE_NAME”, “value”). Rust’s Result-based approach forces explicit error handling, preventing bugs from assuming variables exist.

Most programming languages follow similar patterns: read-only access is simple and straightforward, setting variables affects only the current process and its children, and there’s no standard way to permanently modify system-wide environment variables from application code (as this would require elevated privileges and is generally considered inappropriate for applications to do automatically).

Practical Applications and Use Cases

Environment variables serve numerous practical purposes across different computing scenarios, from simple user customization to complex enterprise application deployment.

Command-line tool accessibility relies heavily on the PATH variable. When you install development tools like Git, Python, Node.js, or compilers, the installers typically add their binary directories to PATH. This allows you to type “git” or “python” from any directory without specifying full paths. Users who install command-line tools manually must add the appropriate directories to PATH themselves, a common source of “command not found” errors when PATH isn’t configured correctly.

Application configuration through environment variables enables the same program binary to behave differently in different environments. A web application might read DATABASE_URL from an environment variable to know which database to connect to, allowing developers to use local databases while production servers connect to production databases, all without code changes. Feature flags can be controlled through environment variables, enabling or disabling features based on the environment. API keys, passwords, and other secrets can be injected through environment variables rather than hardcoded in source code, improving security (though environment variables aren’t secure storage—they’re visible to all processes running under the same user).

Deployment platforms like Heroku, AWS Elastic Beanstalk, and Azure App Service use environment variables extensively for configuration. These platforms allow you to set configuration variables through their web interfaces or command-line tools, and the platform automatically makes these variables available to your deployed applications. This approach enables zero-code-change deployments where the same application package runs in different environments with different configurations injected through environment variables.

Container orchestration systems like Docker and Kubernetes use environment variables as a primary configuration mechanism. Docker containers receive environment variables through the “docker run -e” flag or docker-compose.yml configuration files. Kubernetes ConfigMaps and Secrets get mounted as environment variables in pods, allowing cluster administrators to configure applications without modifying container images. This approach supports the “build once, deploy anywhere” philosophy central to containerization.

Debugging and development workflows often use environment variables for control. Setting DEBUG=1 or DEBUG=* might enable verbose logging in applications that check this variable. Development tools might check variables like DEVELOPMENT or DEV_MODE to enable additional features useful during development but inappropriate for production. Build systems use variables like BUILD_NUMBER or GIT_COMMIT to tag builds with version information.

Cross-platform software development leverages environment variables for portability. A program can check the OS or OSTYPE variable to determine which platform it’s running on and adjust behavior accordingly. It can use TEMP to find the appropriate temporary directory regardless of platform. It can use HOME or USERPROFILE to locate user-specific data in the correct platform-specific location. This variable-based approach is often simpler than embedding platform detection logic throughout the code.

System administration and automation scripts extensively use environment variables. Backup scripts might read configuration from variables to know which directories to backup and where to send backups. Automated deployment scripts might use variables to specify server addresses, credentials, and deployment parameters. Variables allow scripts to be generic and reusable, with behavior controlled through configuration rather than code modification.

User customization of the command-line environment uses variables for personal preferences. Setting EDITOR to your preferred text editor ensures command-line tools use that editor. Setting color scheme variables changes terminal color output. Setting PS1 in bash or PROMPT in PowerShell customizes your command prompt’s appearance. These variables make the command-line environment more personalized and comfortable without requiring system-wide changes.

Multi-user systems use environment variables to maintain per-user configurations. Each user’s PATH might include user-specific directories in their home folder. Each user’s LANG setting might specify different languages. These user-specific variables ensure users can customize their environments without affecting other users on the same system.

Integration testing often uses environment variables to control test behavior. Tests might check a CI variable to know they’re running in a continuous integration environment and adjust timeouts, enable different logging, or skip tests that require interactive user input. Test frameworks might use variables to control test parallelization, retry behavior, or reporting formats.

Security Considerations and Best Practices

While environment variables provide convenient configuration capabilities, they also present security considerations that developers and system administrators must understand and address.

Environment variables are not secure storage for secrets. On Unix-like systems, the /proc/[pid]/environ file exposes any process’s environment variables to anyone who can read that file (typically the process owner and root). On Windows, processes running under the same user account can access each other’s environment variables through Windows APIs. This means that while environment variables can convey secrets from a deployment system to an application, they’re visible to anyone with the appropriate access level, including other processes running under the same account, malware infecting the user account, or administrators. Treat environment variables as having the same security level as command-line arguments—convenient for non-sensitive configuration but inappropriate for long-term secret storage.

Sensitive data in environment variables can leak in several ways. When processes crash, error reports might include environment variable dumps. Log files might inadvertently record environment variables during debugging. Process listing tools might display command-line arguments that include environment variable values. Shell history files record commands that set environment variables, potentially preserving secrets long after they’re no longer needed. Best practice is to minimize the time sensitive data lives in environment variables, loading secrets when needed and clearing them when done.

Applications that log environment variables or include them in error messages should redact sensitive variables. A common practice is maintaining a list of variable names known to contain secrets (like PASSWORD, SECRET_KEY, API_TOKEN) and either excluding them from logs or replacing their values with “[REDACTED]” markers. Automatic redaction prevents accidental secret disclosure while maintaining useful debugging information.

Variable injection attacks can occur when applications construct commands or queries using environment variable values without proper validation or escaping. If an attacker can control an environment variable’s value, they might inject malicious content that gets executed. Applications should validate environment variable values before using them in security-sensitive contexts, treating them as untrusted input similar to user input or network data.

The PATH variable presents specific security risks. If an attacker can modify your PATH to include a directory they control before legitimate directories, they can place malicious executables with names matching common commands (like “ls”, “sudo”, or “python”), which would execute instead of the intended programs. This “PATH hijacking” attack can compromise security significantly. Best practices include ensuring directories in PATH are owned by trusted users with appropriate permissions, listing trusted directories before untrusted ones, and being cautious about adding arbitrary directories to PATH.

Child process inheritance of environment variables means that when a parent process has access to secrets through variables, all child processes inherit those secrets. This might provide more access than intended—a command-line tool that receives a database password through an environment variable and then executes a plugin or helper program inadvertently gives that plugin access to the database password. Minimize secret scope by clearing sensitive variables before spawning child processes that don’t need them, or use process-specific configuration methods instead of environment variables when possible.

Cloud platforms and container systems that inject secrets through environment variables should use their native secret management systems rather than treating secrets as simple configuration. AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, Kubernetes Secrets, and similar systems provide better security through encryption at rest, access auditing, rotation capabilities, and fine-grained access controls. These systems can make secrets available to applications at runtime in ways that limit exposure compared to environment variables.

Configuration management best practices suggest using environment variables for non-sensitive configuration that varies by environment (URLs, feature flags, performance tuning) while using dedicated secret management for sensitive data. The twelve-factor app methodology recommends strict separation of configuration from code, with environment variables as the configuration mechanism, but this recommendation predates modern secret management systems and should be adapted to use appropriate secret handling tools for sensitive data.

Environment variable validation and defaults improve security and reliability. Applications should check that required variables exist before proceeding, validate that values match expected formats or ranges, and provide sensible defaults for non-critical variables. This defensive programming prevents crashes, undefined behavior, or security vulnerabilities from missing or malformed variables.

Documentation of required environment variables helps both users and security auditors understand what configuration an application needs and what permissions it requires. Applications should clearly document which variables they use, whether they’re required or optional, what values are acceptable, and what the security implications of different values are. This transparency enables proper security configuration and risk assessment.

Troubleshooting Common Environment Variable Issues

Environment variable problems frequently cause configuration issues, program failures, and unexpected behavior, but systematic troubleshooting can quickly identify and resolve these problems.

The “command not found” or “program not recognized” error is typically a PATH problem. When you try to run a program and the system reports it can’t find it, the issue is usually that the program’s directory isn’t in the PATH variable, or PATH isn’t set correctly. First, verify the program is actually installed and note its location. Then examine the PATH variable (“echo $PATH” on Unix, “echo %PATH%” on Windows) to see if that location is included. If not, add the directory to PATH following your operating system’s procedures. Remember that PATH changes often require restarting your terminal or shell to take effect.

Programs behaving differently when launched from the command line versus graphically often indicates environment variable differences. On Unix systems, shells load configuration files that set variables when you open a terminal, but graphical applications launched from desktop menus or icons might not inherit those variables. The solution typically involves setting system-wide variables (through /etc/environment or similar mechanisms) or launching programs through scripts that set necessary variables before starting the actual application. On macOS, the environment available to GUI applications differs from terminal environments, requiring special configuration.

“Variable not set” or “undefined variable” errors mean a program is trying to access an environment variable that doesn’t exist. Solutions include setting the variable to an appropriate value, configuring the program to use a different variable or configuration method, or modifying the program to handle missing variables gracefully. Check the program’s documentation to understand what variables it expects and what values are appropriate.

Permission denied errors when setting system-wide variables indicate you lack administrative privileges. On Windows, modifying system environment variables requires administrator access—use “Run as administrator” when opening system settings. On Unix systems, modifying system-wide configuration files requires root access, typically obtained through sudo. User-specific variables can be modified without special privileges.

Environment variable changes not taking effect is a common frustration. After modifying variables, existing shells and programs won’t see changes until they restart. Windows GUI applications might need a logout/login or system restart to see system variable changes. Unix shell sessions need to be restarted or configuration files re-sourced. Some programs cache variable values at startup, requiring application restart rather than just environment refresh.

Conflicting variable values across different scopes (system vs. user, or different shell configuration files) can cause inconsistent behavior. When user variables override system variables or when multiple configuration files set the same variable to different values, the effective value depends on which takes precedence in that context. Debugging requires examining all places variables might be set and understanding precedence rules for your operating system and shell.

Special characters in variable values can cause parsing problems. Spaces, quotes, backslashes, and other characters might require escaping or quoting when setting variables, particularly in shell commands. Windows uses different quoting conventions than Unix shells, causing cross-platform configuration challenges. Testing variables with echo after setting them helps verify the value was set correctly without escaping artifacts.

Variables containing paths can break when paths include spaces or special characters. Wrapping path variables in quotes when using them prevents word splitting errors, and ensuring paths are properly escaped when setting variables prevents parsing problems. On Windows, mixing forward slashes and backslashes in path variables can cause issues with programs expecting specific path separators.

The PATH order affects which program executes when multiple programs with the same name exist in different directories. If the wrong version of a program runs, check PATH’s order—directories earlier in PATH take precedence. Reordering PATH to list preferred directories first resolves version conflicts.

Character encoding issues with variables containing non-ASCII characters can cause problems, particularly on Windows where command prompt and PowerShell use different encodings. Setting LANG and related locale variables to appropriate values helps ensure consistent character handling, though some older Windows tools have limited Unicode support regardless of variable settings.

Environment Variables in Software Development and DevOps

Modern software development and operations practices make extensive use of environment variables as a configuration and deployment mechanism.

The twelve-factor app methodology, a widely-adopted set of best practices for building modern web applications, designates environment variables as the recommended configuration mechanism. Factor III (Configuration) states that applications should store configuration in environment variables rather than configuration files, reasoning that environment variables are easy to change between deployments without changing code, are less likely to be accidentally committed to version control, and are a language- and OS-agnostic standard. While the pure interpretation has been refined over time (particularly regarding secrets), the core principle of using environment variables for configuration that varies between environments remains influential.

Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) systems heavily use environment variables. Jenkins, GitLab CI, GitHub Actions, Travis CI, and other CI/CD platforms inject variables into build environments, providing information like build numbers, commit SHAs, branch names, and configured secrets. Build scripts read these variables to tag builds, determine what to test, decide where to deploy, and access necessary credentials. This variable-based approach allows build scripts to remain generic while the CI/CD platform provides environment-specific values.

Containerized applications with Docker depend on environment variables for runtime configuration. Dockerfiles can set default variable values with the ENV instruction, docker run commands can override these with -e flags, and docker-compose files specify variables in YAML format. Container orchestration platforms like Kubernetes use ConfigMaps to define configuration data and Secrets for sensitive data, both of which can be injected into containers as environment variables. This approach keeps container images generic and reusable across environments.

Cloud-native platforms from AWS Lambda to Google Cloud Functions to Azure Functions use environment variables as their primary configuration interface. You configure function behavior through platform-specific interfaces that translate to environment variables available to your function code. This consistent approach simplifies application code since configuration access is standardized regardless of cloud provider.

Infrastructure as Code tools like Terraform and CloudFormation can read environment variables for configuration, allowing you to avoid hardcoding values or committing sensitive data to version control. A Terraform script might read AWS credentials from AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID and AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY variables, or might use other variables to parameterize infrastructure definitions.

Development environment management tools like direnv automatically load environment variables when you enter a project directory and unload them when you leave, creating project-specific environments. Developers working on multiple projects with different configuration needs can have appropriate variables automatically set for each project, reducing configuration burden and preventing cross-project configuration conflicts.

.env files have become a standard convention for local development configuration. These files contain KEY=VALUE pairs, one per line, defining environment variables for development. Tools like dotenv (available for many languages) load these files when applications start in development mode. .env files are typically excluded from version control (through .gitignore), allowing developers to maintain local configuration without committing potentially sensitive data. Many projects include .env.example files showing required variables without actual values, helping new developers set up their environments.

Environment variable validation libraries help applications fail fast with clear error messages when configuration is missing or invalid. Tools like envalid for JavaScript or python-decouple for Python allow declaring expected variables, their types, default values, and validation rules. The application validates its environment at startup, ensuring all required configuration exists before attempting to run, preventing runtime failures from missing configuration.

Service mesh and microservice architectures use environment variables to configure service discovery, inter-service authentication, observability settings, and circuit breaker parameters. Each service instance receives configuration appropriate to its role and environment through variables injected by the orchestration platform.

Advanced Environment Variable Concepts

Beyond basic variable setting and retrieval, several advanced concepts extend environment variable capabilities and functionality.

Variable expansion and substitution allow referencing variables within variable values. On Unix shells, you can define a variable like “APP_DIR=$HOME/applications” that incorporates the HOME variable’s value. This expansion happens when the variable is set, creating derived variables from existing ones. Windows supports delayed expansion in batch files, where variables are expanded at execution time rather than parse time, enabling more dynamic behavior.

Default values and fallback mechanisms let applications handle missing variables gracefully. Bash supports syntax like “${VARIABLE_NAME:-default_value}” which returns the variable’s value if it exists, or the default value if it doesn’t. Many programming languages provide similar idioms through their environment variable APIs. This capability allows applications to work with sensible defaults when not explicitly configured.

Variable persistence across sessions requires appropriate configuration file editing on most systems. Variables set in shell commands only last for that session unless exported to configuration files read at startup. Understanding which files to modify (.ba.shrc vs .ba.sh_profile vs .profile on Linux, launchd configuration vs shell configs on macOS, System settings vs PowerShell profiles on Windows) ensures variables persist correctly.

Process-specific variables can be set just for one command execution without affecting the broader environment. On Unix shells, prefixing a command with “VARIABLE=value command arguments” sets that variable only for that command’s execution. This technique is useful for temporarily changing behavior without permanently altering the environment.

Variable arrays and complex data structures aren’t directly supported by environment variables, which store only strings. Applications needing structured configuration typically encode it in string format (JSON, comma-separated values, etc.) within variable values and parse it after retrieval. Some shells (like bash) support array variables, but these don’t transfer to child processes through the standard environment mechanism.

Read-only variables can be declared in some shells to prevent modification. Bash’s “readonly VARIABLE_NAME” prevents that variable from being changed or unset in the current shell. This protects critical variables from accidental modification by scripts or commands.

Variable namespacing helps avoid conflicts between applications. By convention, applications prefix their variables with application-specific prefixes (like “MYAPP_DATABASE_URL” rather than just “DATABASE_URL”), reducing the likelihood that multiple applications will try to use the same variable name for different purposes.

Conditional variables or variable sets allow different configuration based on environment type. Applications might check an ENVIRONMENT variable (with values like “development”, “staging”, “production”) and load different sets of configuration variables based on that value. This pattern enables maintaining multiple environment configurations within the same codebase.

Variable export scope determines whether child processes inherit variables. In Unix shells, variables must be explicitly exported to be available to child processes. A variable set with “VARIABLE=value” is local to the shell, while “export VARIABLE=value” makes it available to any programs the shell executes. This distinction allows shell-only variables that don’t propagate to other programs.

Conclusion

Environment variables represent a foundational mechanism through which operating systems provide context, configuration, and communication channels to applications and processes. From their origins in early Unix systems to their central role in modern cloud-native application deployment, environment variables have proven remarkably enduring and useful despite their simplicity. They solve the fundamental problem of how to provide runtime configuration to software without hardcoding values, enabling the same program binary to behave appropriately in different contexts simply by changing the environment in which it runs.

Understanding environment variables—how to view them, set them, manage their scope and persistence, and leverage them appropriately—is essential knowledge for anyone working with operating systems, whether as a developer building applications, a system administrator managing infrastructure, or a power user customizing their computing environment. The ubiquity of environment variables across all major operating systems, programming languages, and deployment platforms makes them a universal skill that applies broadly across the computing ecosystem.

While environment variables have limitations (they’re not secure storage, they can’t elegantly handle complex data structures, and they sometimes suffer from platform-specific quirks), their strengths—simplicity, universal support, easy modification, and process inheritance—ensure they remain relevant even as computing architectures evolve. Modern practices around containerization, cloud deployment, and infrastructure as code have actually increased reliance on environment variables rather than diminishing it, confirming their continued importance in the operating system landscape. Whether you’re troubleshooting why a command isn’t found, configuring a containerized application, or customizing your shell environment, understanding how environment variables work and how your operating system manages them provides practical capabilities that improve your effectiveness in working with computers.

Summary Table: Environment Variable Management Across Operating Systems

| Aspect | Windows | Linux/Unix | macOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage Location | Registry (HKLM and HKCU Environment keys) | Shell configuration files (/etc/environment, ~/.ba.shrc, ~/.profile) | Shell configuration files (~/.zs.hrc, ~/.zprofile) plus launchd for GUI apps |

| Scope Types | System-wide (all users) and user-specific | System-wide (/etc/) and user-specific (~/) | System-wide (/etc/) and user-specific (~/), with GUI vs terminal distinction |

| Viewing All Variables | Command Prompt: setPowerShell: Get-ChildItem Env: | printenv or env | printenv or env |

| Viewing One Variable | echo %VARIABLE% (cmd)$env:VARIABLE (PowerShell) | echo $VARIABLE | echo $VARIABLE |

| Temporary Setting | set VARIABLE=value (cmd)$env:VARIABLE = "value" (PowerShell) | export VARIABLE=value | export VARIABLE=value |

| Permanent Setting | System Properties GUI or setx command | Add to ~/.ba.shrc or /etc/environment | Add to ~/.zs.hrc or system-wide config |

| PATH Separator | Semicolon (;) | Colon (:) | Colon (:) |

| Case Sensitivity | Case-insensitive (PATH = path = Path) | Case-sensitive (PATH ≠ path) | Case-sensitive (PATH ≠ path) |

| Primary Config Tool | System Properties > Environment Variables | Text editor for shell config files | Text editor for shell config files |

| GUI Apps Access | Automatic from Registry | Requires system-wide setting | Requires launchd configuration or system-wide setting |

| Common Temp Variable | TEMP, TMP | TMPDIR, TEMP, TMP | TMPDIR |

| Common Home Variable | USERPROFILE, HOMEPATH | HOME | HOME |

| Common User Variable | USERNAME | USER | USER |

| Shell Variable | ComSpec | SHELL | SHELL |

| Inheritance Behavior | Child processes inherit parent environment | Child processes inherit exported variables | Child processes inherit exported variables |

Common Environment Variables Across All Systems:

| Variable | Purpose | Typical Value Example |

|---|---|---|

| PATH | Directories searched for executables | Windows: C:\Windows\system32;C:\Program Files\Git\binUnix: /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin |

| HOME / USERPROFILE | User’s home directory | Unix: /home/usernameWindows: C:\Users\Username |

| TEMP / TMP | Temporary files directory | Unix: /tmpWindows: C:\Users\Username\AppData\Local\Temp |

| USER / USERNAME | Current user’s login name | john_doe |

| LANG | Locale and language setting | en_US.UTF-8 |

| EDITOR | Preferred text editor | vim, nano, code |

| PWD | Current working directory | /home/username/projects/myapp |

| SHELL | Default command shell | /bin/bash, /bin/zsh |