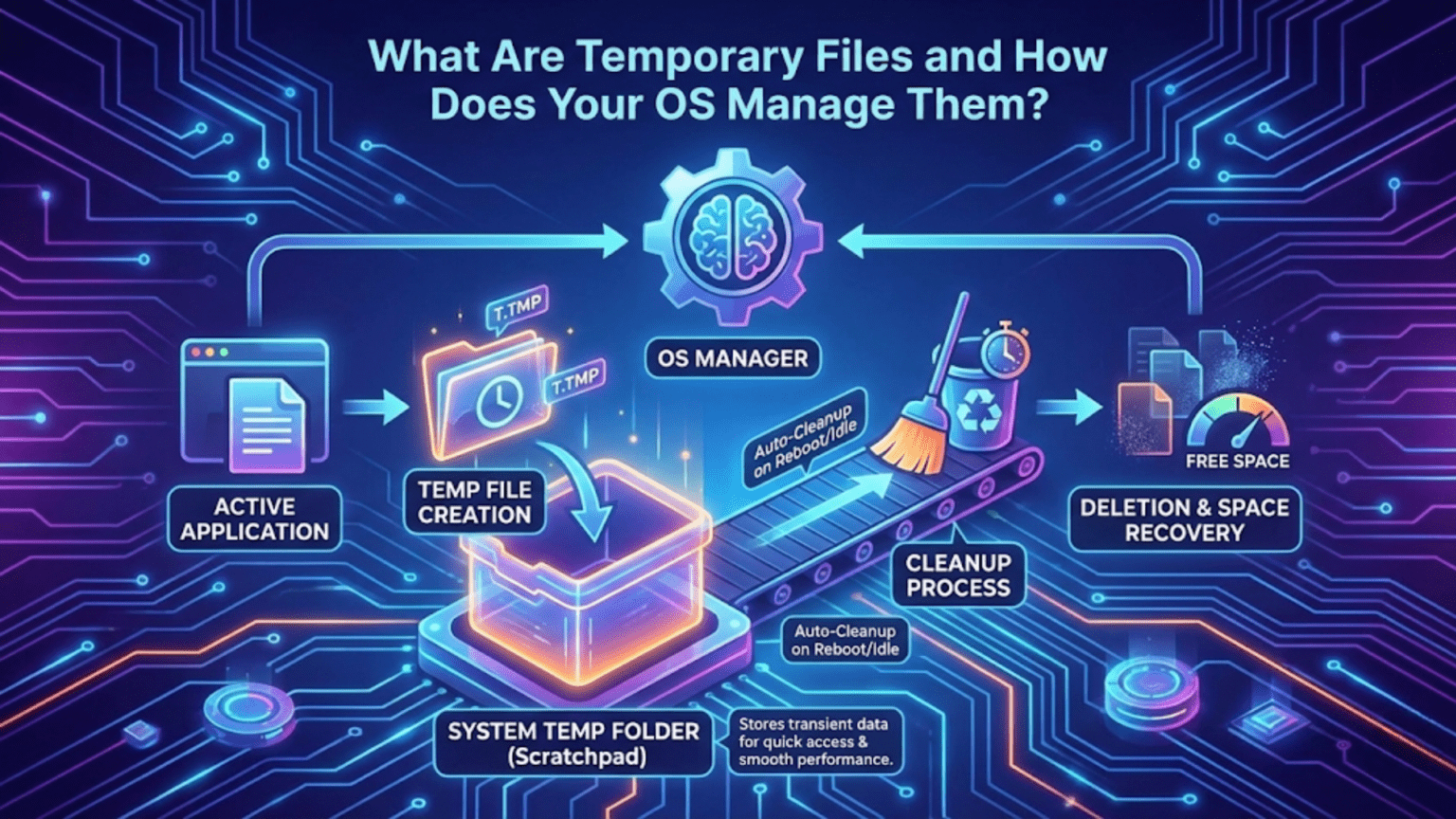

Temporary files are files created by the operating system or applications to store data needed only during a specific operation or session, such as work-in-progress data while editing a document, cached web content for faster loading, installation packages during software setup, or swap data when RAM is insufficient. These files are meant to be deleted after their purpose is served, but operating systems use various strategies to manage their creation, storage, and cleanup since applications don’t always delete them properly.

Your computer constantly creates and discards thousands of files you never see—files that hold partial work while you edit documents, cache websites for faster loading, store installation data during software setup, buffer video as it streams, hold crash information for diagnosis, and perform dozens of other essential temporary functions. These temporary files are a fundamental part of how modern operating systems and applications function, enabling better performance, crash recovery, and efficient use of system resources. Yet they accumulate silently, and without proper management they can consume gigabytes of storage, slow system performance, and occasionally cause problems when they become corrupted or outdated.

Understanding temporary files—what they are, why they exist, where your operating system stores them, how different types serve different purposes, and how the OS manages their lifecycle—provides practical knowledge for maintaining system performance, freeing storage space when needed, and understanding why disk usage grows over time even when you haven’t added files intentionally. Every major operating system implements sophisticated temporary file management balancing the need for quick creation and access against the necessity of eventual cleanup, and these mechanisms reflect interesting design choices about performance, reliability, and storage efficiency. This comprehensive guide explores every aspect of temporary file management across Windows, macOS, and Linux, from the specific locations where different types of temporary files reside to the automatic and manual cleanup mechanisms that prevent them from consuming all available storage.

What Temporary Files Are and Why They Exist

Temporary files serve as working storage for operations that need persistent (on-disk) space during their execution but don’t need to keep that data permanently afterward.

The fundamental reason temporary files exist rather than purely in-memory operations is that RAM is limited and volatile. When working with large documents, video files, or datasets that exceed available RAM, applications must use disk storage as an extension of working memory. A video editor processing a 4K video can’t hold all frames in RAM simultaneously, so it writes intermediate processing results to temporary disk files. A word processor doesn’t keep your entire document in memory while you type—it writes to disk periodically. These on-disk temporary stores make operations possible that would otherwise require impractically large amounts of RAM.

Crash recovery represents another critical reason for temporary files. When you’re editing a document and the application crashes unexpectedly, the only way to recover unsaved work is if the application has been periodically writing your progress to a temporary file. Microsoft Word’s AutoRecover feature saves document state to temporary files every few minutes, enabling it to offer document recovery when reopened after a crash. Without these temporary save files, any application crash would mean losing all work since the last manual save.

Process coordination uses temporary files to pass information between different processes or between different stages of a processing pipeline. A compiler might write intermediate object files that are temporary from the user’s perspective—needed during compilation but not the final output. A print system creates temporary spool files holding print job data while waiting for the printer. A download manager writes temporary files for in-progress downloads, only renaming them to their final names upon completion.

Caching improves performance by storing copies of data that takes time to retrieve or generate in temporary locations for faster reuse. Web browsers cache images, scripts, and page content in temporary directories so pages load faster on repeat visits. Operating system thumbnail caches store pre-rendered thumbnails for photos and documents so file explorer windows load instantly rather than regenerating thumbnails every time. Icon caches store application icons to avoid re-reading executable files repeatedly.

Atomic operations use temporary files to ensure consistency. When an application needs to update a file in a way that would be catastrophic if interrupted partway through—like overwriting a configuration file—it typically writes to a temporary file first, then atomically renames the temporary file to replace the original. If the write fails, the original is intact; if the rename fails, the temporary file can be discarded. This pattern prevents partially-written files that would corrupt data.

Installation processes extensively use temporary files to hold downloaded packages, extracted contents, installation scripts, and intermediate states during software installation. These installation temporaries can be quite large—hundreds of megabytes or more for complex software—and should be cleaned up after installation completes, though they sometimes persist if installation is interrupted or the cleanup code has bugs.

Types of Temporary Files

Temporary files encompass several distinct categories, each serving different purposes with different creation patterns, sizes, and appropriate retention periods.

Application temporary files are created by individual programs to store working data. Every running application that needs to persist intermediate state creates these—document editors writing recovery files, image editors holding undo history on disk, database applications writing transaction logs, compilers writing object code before linking. Application temp files typically live in system-designated temporary directories or application-specific subdirectories and should be deleted when the application exits normally.

Browser cache files store web content for faster reuse. When you visit a website, your browser downloads images, stylesheets, JavaScript files, and other resources. The browser stores these in its cache directory so subsequent visits to the same page can load resources from local storage rather than re-downloading them, dramatically improving page load times. Browser caches can grow to gigabytes for heavy web users and are stored in user-specific locations separate from system temp directories.

System cache files are maintained by the operating system itself for performance optimization. Font caches speed up text rendering by storing pre-processed font data. Icon caches store thumbnail images for quick display in file managers. Package manager caches on Linux store downloaded software packages in case reinstallation is needed. DNS caches store recently resolved domain name lookups. These system caches are managed by the OS and should be cleared carefully, as premature deletion causes performance degradation.

Update and installation temporary files hold software packages and extracted contents during installation processes. Windows Update downloads updates to a cache before installing them. The macOS App Store downloads applications to temporary locations before moving them to Applications. Linux package managers store downloaded packages in cache directories. These files can be large but are safe to delete after installation succeeds.

Swap and page files are special temporary files that extend RAM by storing memory contents on disk when physical RAM is insufficient. Windows creates pagefile.sys, Linux creates swap partitions or swap files, and macOS uses swapfiles in /private/var/vm/. These aren’t temporary in the conventional sense—they persist across sessions—but represent temporary usage of disk space for content that normally lives in RAM.

Log and diagnostic temporary files include crash dumps, diagnostic reports, and application logs that collect information about system events. Windows stores crash dumps in %SYSTEMROOT%\Minidump, macOS saves crash reports in ~/Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports, and Linux applications write to /tmp or application-specific log directories. While important for diagnosis, these accumulate indefinitely without cleanup mechanisms.

Download temporaries are partial files created during downloads that haven’t completed. Browsers and download managers typically name in-progress download files with temporary extensions (.part, .crdownload, .tmp) or store them in temporary directories, moving them to final locations only upon successful completion. Interrupted downloads leave these partial files behind.

Compiled bytecode and generated files represent a category unique to interpreted languages and build systems. Python writes .pyc files alongside .py source files, Java generates .class files, and JavaScript bundlers create output files. These technically aren’t temporary in the traditional sense—they persist intentionally—but they’re derived from source files and can always be regenerated, making them candidates for cleanup when storage space is needed.

Where Temporary Files Are Stored

Each operating system designates specific locations for temporary files, and applications are expected to respect these conventions, though they don’t always do so.

Windows uses several designated temporary file locations with different access levels and purposes. The primary system temporary directory, pointed to by the TEMP and TMP environment variables, is typically %USERPROFILE%\AppData\Local\Temp for user-specific temp files. This path expands to something like C:\Users\Username\AppData\Local\Temp. The system-wide temporary directory used by system processes and services is C:\Windows\Temp. Applications should query the TEMP or TMP environment variables to find the appropriate temporary directory rather than hardcoding paths.

Windows also uses several specialized locations for specific types of temporary data. The Prefetch folder (C:\Windows\Prefetch) stores program launch data that Windows uses to speed up application startup. The Windows Update cache is in C:\Windows\SoftwareDistribution\Download. The Windows Installer cache in C:\Windows\Installer holds installation packages for installed programs. The Windows Error Reporting temporary files appear in %LOCALAPPDATA%\CrashDumps. Browser caches have application-specific locations—Chrome uses %LOCALAPPDATA%\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Cache, Firefox uses %APPDATA%\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles[profile]\cache2.

Linux follows the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) for temporary file locations. /tmp is the primary temporary directory, accessible to all users and typically cleared at each boot (though this varies by distribution and configuration). Files in /tmp that are not accessed for extended periods are also removed by the tmpwatch or systemd-tmpfiles service. /var/tmp is a secondary temporary directory for files that should persist across reboots—applications that need temporary files to survive system restarts should use /var/tmp rather than /tmp.

User-specific temporary directories on Linux are typically /tmp/user/[UID] when running under systemd, or applications might use $XDG_RUNTIME_DIR which points to a user-specific runtime directory (usually /run/user/[UID]). This user-specific runtime directory has a configurable size limit and is automatically cleaned when the user logs out. Application caches go to ~/.cache (following XDG Base Directory specifications), which persists across sessions and is not automatically cleaned.

macOS stores temporary files in /tmp (which is actually a symlink to /private/tmp), in /var/folders/[…]/T/ for user-specific temporary files, and in ~/Library/Caches for application cache files. The /var/folders path is generated uniquely for each user and contains multiple subdirectories (T for temporary, C for cache, and others) that the OS manages. The actual path can be found programmatically using the NSTemporaryDirectory() API call.

macOS places significant emphasis on application sandboxing with respect to temporary files. Sandboxed applications (from the Mac App Store and increasingly all macOS applications) have their temporary files stored in sandbox-specific locations within ~/Library/Containers/[BundleID]/Data/tmp/ or ~/Library/Containers/[BundleID]/Data/Library/Caches/. This isolation means each application’s temporary files are stored separately, making per-application cleanup easier.

Hidden temporary locations include various places applications create temp files outside standard directories. Some applications create temporary files in their installation directories, in the user’s home directory, in the Documents folder, or in other non-standard locations. This poor practice makes comprehensive temporary file management difficult because there’s no single location to check. Security scanning, disk usage analysis tools, and application uninstallers must search broadly to find all application-created temporary data.

How Operating Systems Manage Temporary File Cleanup

The lifecycle management of temporary files—ensuring they’re created when needed and cleaned up when no longer necessary—is a critical OS responsibility that requires balancing multiple competing concerns.

Automatic boot-time cleanup clears certain temporary directories when the system starts. Traditional Unix systems clear /tmp at boot, ensuring each session starts fresh. Many Linux distributions configure systemd-tmpfiles to delete /tmp contents older than a configurable age during boot or periodically. Windows doesn’t systematically clear %TEMP% at boot but does clean up some categories of files. This boot-time cleanup handles files left behind by crashes or unexpected terminations.

Systemd-tmpfiles on modern Linux distributions provides declarative temporary file management through configuration files in /usr/lib/tmpfiles.d/ and /etc/tmpfiles.d/. These configuration files specify directories to create, clean, or remove, with rules defining age thresholds for automatic deletion. For example, a rule might specify that /tmp should have files older than 10 days removed daily. System administrators can add custom rules for application-specific temporary directories.

Application-level cleanup is the primary mechanism by which temporary files should be removed—the application that creates them is responsible for deleting them. Well-designed applications open temporary files, use them for their intended purpose, and delete them before exiting. File handles and corresponding cleanup code ensure deletion happens even if the application encounters errors. The C standard library’s tmpfile() function creates a temporary file that’s automatically deleted when closed, providing cleanup as a first-class feature.

Reference counting and file handle tracking allow operating systems to remove files when no process holds them open. On Unix-like systems, a process can unlink (delete) a temporary file immediately after opening it—the file’s directory entry is removed, making it inaccessible by path, but the file’s data persists as long as any process has it open. When the last file handle closes, the operating system automatically frees the storage. This technique ensures cleanup even if the application crashes, because closing all open file handles is automatic when a process terminates.

Disk Cleanup on Windows (cleanmgr.exe) provides a graphical tool for identifying and removing categories of temporary files with user control. It analyzes temporary internet files, downloaded program files, recycle bin contents, temporary files, thumbnail cache, Windows error reports, delivery optimization files, and others, showing how much space each category occupies and allowing selective deletion. Windows 10 and 11 incorporate Disk Cleanup functionality into Storage Settings under Temporary Files, providing a more integrated interface.

Storage Sense on Windows 10 and 11 provides automatic temporary file cleanup triggered by storage pressure or on a schedule. When enabled, Storage Sense automatically deletes temporary files, empties the Recycle Bin after a configured period, and can delete locally cached versions of OneDrive files not recently accessed. Users configure Storage Sense’s aggressiveness through Storage settings, balancing automatic cleanup against ensuring recently used files remain accessible.

macOS’s automatic cleanup relies on the operating system managing its own temporary and cache locations plus periodic maintenance scripts. macOS runs daily, weekly, and monthly maintenance scripts (formerly via cron, now via launchd) that perform various cleanup operations including clearing system caches, removing old log files, and other maintenance. The operating system also automatically purges memory-mapped cache files when storage space is needed, since these can always be regenerated.

Linux tmpfs filesystems for /tmp mount the directory on a RAM-based filesystem that inherently temporary. Content stored in tmpfs exists only in RAM (and potentially swap), meaning it vanishes when the system shuts down without consuming persistent storage space. Modern systemd-based Linux distributions often mount /tmp as tmpfs, providing automatic cleanup while also limiting temp storage to a portion of available RAM.

Temporary Files and System Performance

The relationship between temporary files and system performance is bidirectional—temporary files support performance through caching, but mismanaged temporaries degrade it.

Cache effectiveness directly impacts system responsiveness. Browser caches prevent redundant downloads, reducing page load times from seconds to milliseconds for cached content. System caches like font caches and icon caches prevent expensive regeneration operations on every access. Thumbnail caches make file manager browsing of image directories nearly instant. These performance benefits are why caches exist and why aggressive cache clearing degrades performance even while freeing space.

Disk space pressure from excessive temporary files degrades overall performance. When disks become very full (above 90-95% capacity), file system performance often degrades because the file system struggles to find free space for new writes. Virtual memory paging and swapping become slower when the disk containing swap files is nearly full. Applications that need to create temporary files may fail entirely if no space is available.

Fragmentation from temporary file creation and deletion historically affected spinning hard drives significantly. Temporary files are created and deleted frequently, generating many small free spaces scattered throughout the disk. New files wrote into these spaces, fragmenting them across many locations. SSDs don’t suffer from traditional fragmentation performance issues, but even SSDs have reduced write performance at high capacity utilization due to requiring garbage collection before writes can complete.

I/O patterns from cache files affect storage device performance characteristics. Cache files in locations with many small random writes stress storage differently than sequential large writes. SSDs handle these patterns well compared to spinning drives, which is one reason SSD adoption improved overall system responsiveness significantly—the random I/O patterns common to cache and temporary file operations benefit most from SSD’s architecture.

Memory-mapped caches like Windows SuperFetch and macOS’s unified buffer cache use RAM to cache frequently accessed files, including temporary and cache files. When a cached file is accessed again, the OS serves it from RAM rather than reading from disk, providing near-instant access. The OS dynamically manages which files to keep in this cache based on access patterns, automatically promoting frequently accessed temporary files to RAM-cached status.

Security Implications of Temporary Files

Temporary files present security considerations that both operating systems and applications must handle carefully.

Sensitive data in temporary files creates exposure risks. When applications process sensitive information—passwords, encryption keys, personal documents, financial data—that information may temporarily reside in temp files. If these files aren’t properly secured and cleaned up, sensitive data persists in plaintext form longer than necessary. Proper temporary file handling requires creating files with restrictive permissions, writing sensitive content securely, and ensuring deletion happens reliably.

Temporary file race conditions, known as TOCTOU (Time of Check to Time of Use) vulnerabilities, occur when attackers manipulate temporary files between when a program checks a file and when it uses it. If an application creates a predictably named temporary file in a world-writable directory like /tmp, an attacker can create a symlink with that name before the application does, causing the application to write to the attacker’s target. Using functions that create temporary files with unique, unpredictable names (mkstemp() on Unix, GetTempFileName() on Windows) mitigates these attacks.

Browser cache privacy deserves special attention. Browser caches contain records of every website visited, including content from HTTPS sites that are otherwise encrypted in transit. Someone with access to the cache directory can reconstruct browsing history and view cached page content. Private browsing modes specifically avoid writing to persistent caches. Clearing browser data, including cache, is a standard privacy practice before returning shared computers.

Malware hiding in temporary directories exploits the fact that temp directories are often excluded from security monitoring and users rarely inspect them. Malware frequently stages itself in %TEMP%, /tmp, or similar locations during installation, and sometimes operates permanently from these locations since they’re writable without special permissions. Security software must scan temporary directories, and users who find unexpected executable files (.exe, .dll, .bat on Windows; .sh, .elf on Linux) in temp directories should treat them as suspicious.

Swap file security concerns arise because memory contents, including potentially sensitive application data, get written to swap files on disk when RAM is full. Encrypting swap space (which Linux supports through dm-crypt and Windows through BitLocker) prevents reading sensitive swapped-out data from a stolen drive. macOS automatically encrypts swap files since OS X 10.7.

Deleted temporary file recovery is possible with forensic tools because file deletion typically just removes directory entries rather than securely overwriting file contents. On traditional HDDs, undeleted temporary file content persists until overwritten. SSDs with TRIM support attempt to erase deleted blocks faster, but timing is not guaranteed. For sensitive operations, secure deletion (overwriting content before deletion) prevents recovery, though SSD wear-leveling makes even this uncertain.

Temporary Files Across Different Scenarios

Different computing scenarios generate different patterns of temporary file creation and have different cleanup requirements.

Software development generates large volumes of temporary files through compilation, testing, and build processes. Build directories (cmake-build-debug, .gradle, target/) accumulate compiled artifacts, dependency caches, and intermediate files that can occupy gigabytes. Development environments with many projects can fill disks with these files. Build tools like Maven, Gradle, npm, and pip each have their own cache and temporary file conventions. Developers periodically run cleanup commands (mvn clean, gradle clean, npm cache clean) to free space while understanding that initial rebuilds after cleanup will be slower as caches regenerate.

Virtual machines and containers use temporary files extensively. Virtual machine snapshots are effectively large temporary files capturing complete VM state at a point in time. Docker layers use a copy-on-write filesystem where modifications create new layers that are temporary until committed. Kubernetes pods leave behind temporary container filesystems. Managing these virtualization temporaries requires understanding which are genuinely no longer needed versus which represent current state.

Scientific and data processing workloads may create enormous temporary files—terabytes during large dataset processing. High-performance computing systems dedicate fast scratch storage specifically for these temporary files, configured to be automatically cleared after job completion. Managing temporary storage for these workloads requires explicit allocation and tracking rather than relying on general-purpose temp directory management.

Mobile operating systems manage temporary files under tighter constraints than desktop systems, given limited storage on mobile devices. iOS and Android aggressively manage cache files, allowing the OS to evict application caches when storage is needed. Applications can observe low-storage notifications and proactively clean their caches. iOS’s “offload unused apps” feature removes app binaries while keeping documents and data, essentially treating installed app code as a large cache.

Tools for Managing Temporary Files

Various tools help users and administrators identify, analyze, and clean up temporary files across different operating systems.

BleachBit is an open-source cleaning tool available for Windows and Linux that scans for and removes temporary files from applications, browsers, the operating system, and various caches. It provides granular control over which categories to clean, showing size estimates before deletion. BleachBit covers thousands of application-specific temp file locations that general system tools miss.

Windows built-in tools beyond Disk Cleanup include the Storage section in Settings showing per-category storage breakdown and the Temporary Files subcategory enabling selective deletion. The Windows 11 version provides more detailed breakdowns and direct access to cleanup actions. PowerShell scripts automate cleanup: “Remove-Item $env:TEMP* -Recurse -Force” clears user temp files programmatically for deployment in enterprise environments.

On macOS, third-party utilities like CleanMyMac or OnyX scan for various categories of potentially cleanable files, though Apple’s own maintenance scripts handle most routine cleanup. The built-in Storage Management utility (Apple menu > About This Mac > Storage > Manage) provides recommendations for freeing space including identifying cached files and temporary items.

Linux command-line tools provide flexible cleanup options. The du (disk usage) command analyzes space consumption: “du -sh /tmp/*” shows size of files and directories in /tmp. The find command locates old files: “find /tmp -mtime +7 -delete” deletes files in /tmp older than 7 days. Package manager cache cleanup (apt clean, dnf clean all, pacman -Sc) removes downloaded package files that are no longer needed.

WinDirStat (Windows) and Baobab/Disk Usage Analyzer (Linux/GNOME) provide visual disk usage analysis, helping identify large temporary file accumulations. These tools display disk contents as treemaps where size corresponds to visual area, making large temporary file directories immediately visible.

Browser-specific cleanup tools are built into every major browser. Chrome’s “Clear browsing data” (Settings > Privacy and Security), Firefox’s “Clear Data” (Preferences > Privacy & Security), and Safari’s “Manage Website Data” all provide control over cache, cookies, and temporary site data. These browser-side cleanups complement OS-level cleanup since browsers manage their caches independently from standard system temp directories.

Conclusion

Temporary files are an unavoidable and essential aspect of modern computing—they enable crash recovery, support performance through caching, allow large file operations within limited RAM, and facilitate safe atomic file updates. Understanding that they exist, why they’re created, where they live, and how operating systems manage their lifecycles transforms them from mysterious disk-space consumers into comprehensible components of operating system architecture serving important purposes.

Effective temporary file management requires balancing multiple considerations: cleaning enough to prevent storage exhaustion while preserving caches that benefit performance, removing genuinely obsolete files while keeping recovery data that might be needed, securing sensitive temporary content while maintaining accessibility for legitimate use, and automating routine cleanup while providing user control for exceptional circumstances. Modern operating systems implement increasingly sophisticated approaches to this balance, from Windows Storage Sense’s automatic cleanup policies to Linux’s tmpfs RAM-based temporary directories to macOS’s automatic cache eviction under storage pressure.

For everyday users, the practical implications are straightforward: enable automatic cleanup mechanisms, periodically run disk cleanup tools when storage is tight, clear browser caches for privacy when needed, and trust that modern operating systems handle most temporary file management without requiring constant manual intervention. For developers and administrators, the deeper understanding of temporary file mechanics supports better application design (creating files in appropriate locations, implementing cleanup code properly), system maintenance (knowing which caches can be safely cleared and which shouldn’t be), and security practices (handling sensitive temporary data with appropriate precautions).

Summary Table: Temporary File Locations Across Operating Systems

| Category | Windows Location | macOS Location | Linux Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| User Temp Files | %USERPROFILE%\AppData\Local\Temp (%TEMP%) | /var/folders/…/T/ (TMPDIR env var) | /tmp, $XDG_RUNTIME_DIR/tmp |

| System Temp Files | C:\Windows\Temp | /private/tmp | /tmp, /var/tmp |

| Application Caches | %LOCALAPPDATA%[App]\Cache | ~/Library/Caches/[BundleID]/ | ~/.cache/[AppName]/ |

| Browser Cache (Chrome) | %LOCALAPPDATA%\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Cache | ~/Library/Caches/Google/Chrome/Default/Cache | ~/.cache/google-chrome/Default/Cache |

| Browser Cache (Firefox) | %APPDATA%\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles[profile]\cache2 | ~/Library/Caches/Firefox/Profiles/[profile]/cache2 | ~/.cache/mozilla/firefox/[profile]/cache2 |

| Windows Update Cache | C:\Windows\SoftwareDistribution\Download | N/A | /var/cache/apt/archives/ (Debian) |

| Package Manager Cache | C:\Windows\Installer | N/A | /var/cache/apt/ (Debian), /var/cache/dnf/ (Fedora) |

| Crash Dumps/Reports | %LOCALAPPDATA%\CrashDumps, C:\Windows\Minidump | ~/Library/Logs/DiagnosticReports | /var/crash/, ~/.local/share/apport/ |

| Virtual Memory Swap | C:\pagefile.sys, C:\swapfile.sys | /private/var/vm/swapfile* | /swap or swap partition |

| Thumbnail Cache | %LOCALAPPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Explorer | N/A (managed by OS) | ~/.cache/thumbnails/ |

| Font Cache | C:\Windows\ServiceProfiles\LocalService\AppData\Local\FontCache | /Library/Caches/com.apple.ATS | ~/.cache/fontconfig/ |

| Prefetch/Launch Data | C:\Windows\Prefetch | N/A (managed differently) | N/A |

Temporary File Types and Management Approaches:

| Type | Created By | Typical Size | Auto-Cleaned? | Manual Cleanup Safety | Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Browser Cache | Web browsers | 100MB–10GB | Partially (browser limits) | Safe anytime | Low (cache rebuilt) |

| App Temp Files | Applications | Varies widely | On app exit (normally) | Safe if app not running | Low |

| Update Cache | OS/package managers | 100MB–5GB | After installation | Safe after updates complete | Medium |

| Crash Dumps | OS/applications | 100MB–several GB | No | Safe after issue resolved | Medium |

| Thumbnail Cache | OS/file managers | 10MB–1GB | Partially | Safe (rebuilt on access) | Low |

| Swap/Page Files | OS | Size of RAM or more | No (system-managed) | Never delete manually | Critical |

| Font Cache | OS | 10–100MB | On corruption detection | Safe (rebuilt on demand) | Medium |

| AutoRecover Files | Office applications | 1MB–100MB | On clean app exit | Only if saved/no longer needed | High |

| Download Partials | Browsers/managers | Varies | Only if completed | Safe if download abandoned | Medium |

| Build Artifacts | Compilers/build tools | 100MB–50GB+ | No | Safe (rebuilt by build system) | Low |