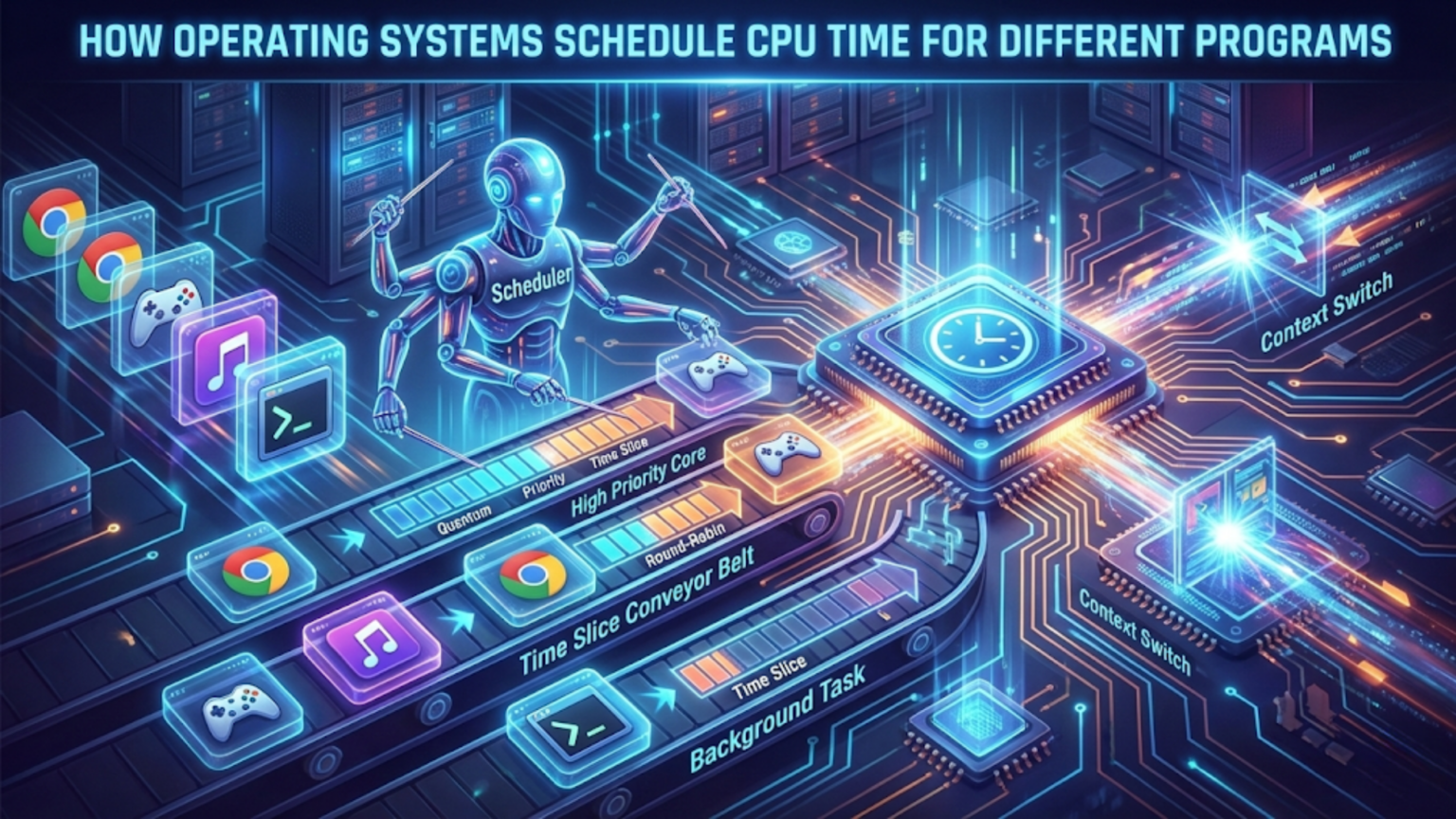

Operating systems schedule CPU time by using scheduling algorithms that determine which program or process runs on the processor at any given moment. The scheduler assigns CPU time slices to waiting processes based on priorities, fairness policies, and scheduling algorithms like Round Robin, Priority Scheduling, or Multilevel Feedback Queues, constantly switching between programs to create the illusion that multiple programs run simultaneously even on single-core processors.

When you’re browsing the web while listening to music, downloading files, and running a virus scan in the background, your computer appears to do all these things simultaneously. Yet unless you have a processor core dedicated to each task, your CPU can actually execute only one instruction stream at a time. The magic that makes everything seem simultaneous is CPU scheduling—one of the most critical functions your operating system performs. The scheduler is the component that decides which program gets to use the CPU and for how long, switching between programs so quickly and efficiently that you perceive smooth, concurrent operation of multiple applications. Understanding how operating systems schedule CPU time reveals the sophisticated algorithms and policies that allow modern computers to juggle dozens or hundreds of processes while maintaining responsiveness and fairness.

CPU scheduling represents a fundamental challenge in operating system design: how to share a limited resource (processor time) among competing demands (all the programs that want to execute) in ways that are fair, efficient, responsive, and predictable. Different programs have different needs—some require consistent timing for smooth video playback, others need maximum throughput for batch processing, and interactive applications need quick response to user input. The operating system’s scheduler must balance these competing requirements, making thousands of scheduling decisions per second while maintaining overall system performance. This comprehensive guide explores how operating systems approach CPU scheduling, the algorithms they employ, how they determine which processes run when, the concept of process priority, and how modern multi-core processors complicate and enhance scheduling capabilities.

The Fundamentals of CPU Scheduling

CPU scheduling becomes necessary whenever there are more programs ready to run than there are available processor cores. On a single-core system, only one instruction stream can execute at any instant, even though you might have dozens of programs open. On a quad-core system, four instruction streams can execute truly simultaneously, but if you have forty programs wanting to run, scheduling is still required to share those four cores among the forty programs.

The core concept underlying CPU scheduling is the context switch. When the operating system decides to stop running one process and start running another, it performs a context switch—saving the complete state of the currently running process (including all register values, program counter, stack pointer, and other processor state) and loading the saved state of the process being switched to. Context switches have overhead (they consume time without doing useful work), so schedulers try to minimize unnecessary switching while still maintaining responsiveness and fairness.

Processes exist in several states that affect scheduling decisions. A process in the running state is currently executing on a CPU core. A process in the ready state wants to run and could execute if assigned a CPU, but is currently waiting for the scheduler to select it. A process in the waiting or blocked state is not ready to run because it’s waiting for something—user input, disk I/O completion, network data arrival, or another process to release a resource. The scheduler only considers processes in the ready state when making scheduling decisions, since blocked processes can’t productively use CPU time even if given it.

The ready queue (or run queue) is a data structure the scheduler maintains containing all processes in the ready state. When a process becomes ready to run (either a new process is created, a blocked process receives the event it was waiting for, or a running process’s time slice expires), it enters the ready queue. The scheduler selects processes from this queue to run, using algorithms we’ll explore later to determine selection order.

CPU scheduling decisions happen at specific moments called scheduling points. A non-preemptive scheduler makes decisions only when the running process voluntarily gives up the CPU (by blocking on I/O, explicitly yielding, or terminating). A preemptive scheduler can also make decisions at any time, forcibly taking the CPU away from a running process. Modern operating systems use preemptive scheduling to prevent misbehaving or CPU-intensive processes from monopolizing the processor.

The timer interrupt makes preemptive scheduling possible. The operating system programs a hardware timer to interrupt the processor at regular intervals (typically every few milliseconds). When the timer fires, control transfers to the OS scheduler, which can decide whether to let the current process continue or switch to a different process. This timer tick is the heartbeat of preemptive scheduling, ensuring the scheduler regains control even if the running process never blocks or yields.

Scheduling goals vary by system type but generally include maximizing CPU utilization (keeping the processor busy with useful work rather than idle), maximizing throughput (completing more processes per unit time), minimizing turnaround time (the time from process submission to completion), minimizing waiting time (time processes spend in the ready queue), minimizing response time (time from request to first response, particularly important for interactive systems), and ensuring fairness (giving all processes reasonable CPU access). Different scheduling algorithms make different tradeoffs among these goals.

Process Priority and Nice Values

Not all processes are equally important. Operating systems implement priority systems that allow some processes to receive preferential CPU access over others, enabling critical system tasks to run smoothly while less important background work proceeds when resources are available.

Process priority is typically represented as a numerical value, though whether higher numbers mean higher or lower priority varies by system. Windows uses priority classes (Realtime, High, Above Normal, Normal, Below Normal, Idle) combined with relative thread priorities within each class, creating a range of 32 priority levels (0-31). Linux traditionally used nice values ranging from -20 (highest priority) to +19 (lowest priority), though modern Linux kernels use these to calculate a wider priority range internally.

The “nice” concept originated in Unix with the idea that “nice” processes are considerate and willing to yield CPU time to others. A process with a high nice value (lower priority) is being nice by not demanding much CPU time, while a process with a low nice value (higher priority) is less nice, demanding more resources. Users can launch programs with specific nice values using the nice command (“nice -n 10 program” runs program with nice value 10), and can adjust running processes with renice.

Static priority represents a process’s base priority level, set when the process is created or explicitly modified. This static priority provides the foundation for scheduling decisions but isn’t the whole story. Dynamic priority is calculated by the scheduler based on static priority plus adjustments from various factors like how much CPU time the process has recently used, how long it’s been waiting, and its behavior pattern.

Interactive vs. CPU-bound process distinction affects priority. Interactive processes spend most of their time waiting for user input, briefly using CPU when input arrives, then blocking again. CPU-bound processes want to use CPU continuously for computation. The scheduler detects these patterns—processes that frequently block and use short CPU bursts are likely interactive and receive priority boosts to maintain responsiveness. Processes that consume their entire time slice every time they run are likely CPU-bound and may receive lower dynamic priority to prevent starving interactive processes.

Priority inversion is a problem where a low-priority process holds a resource (like a lock) that a high-priority process needs, but the high-priority process can’t run because it’s blocked waiting for the resource, while the low-priority process can’t run to release it because medium-priority processes keep preempting it. This can cause the high-priority process to wait indefinitely. Operating systems solve priority inversion through priority inheritance (temporarily elevating the low-priority process’s priority while it holds the needed resource) or priority ceiling protocols (running any process that acquires a shared resource at a priority level sufficient to prevent preemption by any process that might need that resource).

Real-time priority is a special high-priority range used by time-critical processes that need guaranteed scheduling behavior. Real-time processes in Linux (scheduled under SCHED_FIFO or SCHED_RR policies) run at priorities higher than any normal process and preempt normal processes immediately. Windows has a Realtime priority class for similar purposes. Real-time priority must be used carefully—a runaway real-time process can lock up the system by preventing normal processes (including system processes) from running.

User vs. kernel mode affects scheduling. When a process executes in kernel mode (during system calls or device driver code), it typically runs at elevated priority because kernel operations often need to complete quickly to maintain system stability. The scheduler tracks time spent in user mode separately from kernel mode for accounting and scheduling purposes.

Group scheduling or control groups allow managing priorities for groups of processes collectively. Linux control groups (cgroups) can limit CPU usage for entire process trees, useful for containerization. Windows job objects provide similar capabilities. This group-level control enables guarantees like “all processes in this container can use at most 50% of CPU” regardless of how many processes the container runs.

Common Scheduling Algorithms

Operating systems employ various scheduling algorithms, each with different characteristics, advantages, and appropriate use cases. Most modern OS use sophisticated combinations of multiple algorithms rather than relying on a single approach.

First-Come, First-Served (FCFS) is the simplest scheduling algorithm. Processes are executed in the order they enter the ready queue, like a checkout line at a store. The first process runs until it blocks or terminates, then the next process runs, and so on. FCFS is easy to implement with a simple FIFO queue, but it has significant drawbacks. If a long-running process arrives first, shorter processes must wait (the convoy effect), leading to poor average waiting time. FCFS is non-preemptive, so a CPU-intensive process can monopolize the processor. Few modern operating systems use pure FCFS, though it sometimes serves as the algorithm within a priority level.

Shortest Job First (SJF) always runs the process with the shortest expected CPU burst next. If processes A, B, and C need 10, 5, and 2 units of CPU time respectively, SJF would run C, then B, then A. This algorithm provably minimizes average waiting time—running short jobs first means more jobs complete quickly, reducing total waiting. However, SJF is impractical for general-purpose operating systems because there’s no way to know how long a process will run before completion. Even predicting the next CPU burst (time until the process blocks) is difficult. SJF can also cause starvation—long processes might never run if short processes keep arriving.

Shortest Remaining Time First (SRTF) is the preemptive version of SJF. When a new process arrives, the scheduler compares its predicted CPU burst with the remaining time of the currently running process and runs whichever is shorter. SRTF has even better average waiting time than SJF but shares its prediction difficulty and can cause more context switches.

Priority Scheduling runs processes in order of priority, with the highest-priority ready process always running. This algorithm can be preemptive (a high-priority process immediately preempts a lower-priority one) or non-preemptive (the running process completes its burst even if higher-priority processes arrive). Priority scheduling naturally expresses importance differences between processes but can cause starvation—low-priority processes might never run if high-priority processes keep arriving. Aging solves starvation by gradually increasing process priority the longer they wait, eventually elevating even low-priority processes enough to run.

Round Robin (RR) is a preemptive algorithm designed for time-sharing systems. The ready queue is treated as a circular queue. Each process gets a small unit of CPU time called a time quantum or time slice (typically 10-100 milliseconds). When a process’s quantum expires, the scheduler preempts it and moves it to the end of the ready queue, then runs the next process. Round Robin provides fairness—every process gets regular CPU access regardless of length. It’s responsive to interactive processes since no process monopolizes the CPU. The quantum size is critical: too large approaches FCFS behavior, too small wastes time on context switches. Round Robin is a foundation of many modern schedulers.

Multilevel Queue Scheduling partitions the ready queue into multiple separate queues, each with its own scheduling algorithm. For example, you might have a foreground queue for interactive processes scheduled with Round Robin and a background queue for batch processes scheduled with FCFS. Processes are permanently assigned to queues (often based on process type, priority, or other characteristics). Each queue has a priority relative to other queues, or the scheduler might allocate CPU time between queues (like 80% to foreground, 20% to background). This approach allows different algorithms for different process types but lacks flexibility—processes can’t move between queues as their behavior changes.

Multilevel Feedback Queue Scheduling extends multilevel queues by allowing processes to move between queues based on behavior. New processes start in the highest-priority queue. If a process uses its entire time quantum, it drops to a lower-priority queue (it’s CPU-bound, so give it lower priority). If a process blocks frequently (interactive behavior), it stays in or moves to higher-priority queues. Each queue might have different quantum sizes—high-priority queues use small quanta for responsiveness, low-priority queues use large quanta for efficiency. Multilevel feedback queues provide excellent balance between interactive response and batch throughput, adapting to process behavior automatically. Most modern operating systems use variants of this algorithm.

How Modern Operating Systems Implement Scheduling

Real-world operating systems implement sophisticated schedulers that combine and extend the basic algorithms with additional features and optimizations.

The Linux Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS), introduced in kernel 2.6.23, represents the current Linux approach. CFS tries to give each process an equal share of CPU time. It tracks the virtual runtime (vruntime) of each process—the amount of time the process has run, weighted by its priority. CFS always runs the process with the lowest vruntime, gradually balancing runtime across all processes. CFS uses a red-black tree (a self-balancing binary search tree) to efficiently find the process with minimum vruntime. Time slices aren’t fixed; instead, CFS calculates them based on the number of runnable processes and a target latency (how long CFS tries to run each process at least once). For nice values, CFS adjusts the rate at which vruntime accumulates—higher-priority processes accumulate vruntime more slowly, so they run more often.

Windows uses a multilevel feedback queue with 32 priority levels (0-31). Priority levels 16-31 are the real-time priority range, while 0-15 are the variable priority range. Processes in the variable range experience dynamic priority adjustments. Windows uses priority boosts for specific situations: when a process has been waiting for I/O, when GUI window receives input, or when foreground/background status changes. Windows implements thread scheduling rather than process scheduling—each thread in a process is scheduled independently, with threads competing for CPU based on their individual priorities. Windows uses a quantum-based Round Robin within each priority level, with quantum sizes configurable based on whether the system is optimized for foreground or background performance.

macOS uses a multilevel feedback queue scheduler similar to traditional Unix but with enhancements. macOS differentiates between interactive and batch processes, automatically adjusting priorities based on behavior. The scheduler considers factors like whether a process is in the foreground application, whether it’s handling user events, and its recent CPU usage pattern. macOS also implements Quality of Service (QoS) classes where developers can mark threads with priority hints like User Interactive, User Initiated, Utility, or Background, allowing the scheduler to make better decisions about which threads are time-sensitive.

FreeBSD’s ULE scheduler (the default since FreeBSD 7.1) uses a multilevel feedback queue with sophisticated load balancing across multiple CPUs. ULE maintains per-CPU run queues to improve cache locality and reduce locking overhead. It implements CPU affinity, preferring to run threads on the same CPU they ran on previously to benefit from cached data. ULE uses a concept of “interactivity score” to identify interactive processes and give them priority boosts.

Real-time operating systems (RTOS) used in embedded systems use simpler, more predictable schedulers. Many RTOS use fixed-priority preemptive scheduling where each task has a static priority and the highest-priority ready task always runs. This simplicity allows formal analysis of scheduling behavior, proving that critical tasks will meet timing deadlines—essential for systems controlling machinery, medical devices, or automotive functions where missed deadlines could cause catastrophic failures.

Multi-Core and Multi-Processor Scheduling

Modern computers have multiple processor cores, adding complexity and opportunity to CPU scheduling. Multi-core scheduling must not only decide which process runs next but also on which core it should run.

Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP) is the common multi-core architecture where all cores are identical and share access to system memory. The scheduler must distribute processes across cores to maximize parallelism while managing core-specific considerations like cache state and thermal constraints.

Load balancing aims to distribute processes evenly across cores to prevent some cores from being overloaded while others sit idle. The scheduler might use push migration (a busy core pushes some processes to idle cores) or pull migration (an idle core pulls processes from busy cores). Balancing must be frequent enough to maintain even distribution but not so aggressive that processes bounce between cores excessively.

Processor affinity refers to the tendency to run a process on the same core repeatedly. Soft affinity means the scheduler prefers keeping processes on their previous core but will migrate if necessary for load balancing. Hard affinity means the process is pinned to specific cores and never migrates. Affinity matters because when a process runs on a core, that core’s caches fill with the process’s data. Migrating to a different core means starting with cold (empty) caches, causing cache misses and slower execution initially. The scheduler balances affinity benefits (warm caches) against load balancing needs (distributing work evenly).

Per-core run queues are a common implementation approach where each core maintains its own queue of ready processes. This reduces lock contention (cores aren’t fighting for access to a single global queue) and improves cache locality. However, it requires work-stealing mechanisms where idle cores steal processes from busy cores’ queues to maintain balance.

NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) architectures complicate scheduling further. In NUMA systems, memory is physically divided among processor groups, and each processor group can access its local memory faster than remote memory belonging to other groups. The scheduler should consider memory locality when placing processes, preferring to run processes on cores that have fast access to the memory the process uses. Linux’s NUMA-aware scheduler tracks which memory nodes a process uses and tries to schedule it on cores close to that memory.

Simultaneous Multithreading (SMT), marketed as Hyper-Threading by Intel, allows a single physical core to execute two threads concurrently by duplicating some processor resources (like architectural state) while sharing others (like execution units). The OS sees a Hyper-Threaded quad-core processor as eight logical processors. Scheduling for SMT requires understanding that two threads on the same physical core share resources and might interfere with each other, while two threads on different physical cores have independent resources. Some schedulers implement SMT-aware scheduling that prefers spreading processes across physical cores before fully utilizing SMT, or that carefully pairs compatible processes on SMT siblings.

Gang scheduling is relevant for parallel applications that use multiple threads expecting to run simultaneously. If a parallel program has four threads that frequently synchronize with each other, ideally all four should run at the same time on different cores. Otherwise, threads waste time waiting for their siblings that aren’t currently scheduled. Gang scheduling tries to schedule all threads of a parallel application simultaneously, though implementing this perfectly is difficult given the dynamic nature of thread creation and termination.

Core parking is a power-saving technique where the operating system stops scheduling work on some cores and places them in low-power states when the system is lightly loaded. As load increases, the OS “unparks” cores and begins using them. This reduces power consumption while maintaining the ability to use all cores when needed.

Scheduling Interactive vs. Background Processes

Operating systems distinguish between interactive processes that need quick response to user input and background processes that perform work without immediate user visibility, applying different scheduling strategies to each.

Interactive processes are characterized by short CPU bursts alternating with waiting for user input or GUI events. A text editor process spends most of its time blocked waiting for keystrokes, briefly activating to process each character typed, then blocking again. Responsiveness is critical for interactive processes—delays between user action and system response create perceived sluggishness. The scheduler gives interactive processes priority and short time quanta to ensure quick response.

Background or batch processes often perform CPU-intensive computation, file processing, or data analysis without immediate user interaction. These processes can tolerate longer wait times and benefit from longer time quanta (fewer context switches improve throughput). The scheduler gives them lower priority to prevent interfering with interactive responsiveness but ensures they still make progress.

Detecting interactive behavior happens through heuristics. The scheduler monitors how processes use their time slices. Processes that frequently block before their quantum expires are likely interactive. Processes that consistently use their entire quantum are likely CPU-bound. The scheduler adjusts dynamic priorities accordingly—interactive processes get priority boosts, CPU-bound processes get deprioritized.

Foreground vs. background application status affects scheduling. The currently focused application window is the foreground application, while others are background. Operating systems often give foreground applications priority boosts. Windows increases quantum sizes for foreground threads. macOS’s App Nap reduces CPU allocation and priority for background applications that aren’t doing visible work. These policies ensure the application the user is actively using feels responsive even when many background applications are running.

I/O-bound processes spend most time waiting for I/O operations to complete. When disk or network I/O completes, these processes should run quickly to process the data and potentially issue more I/O, keeping I/O devices busy. The scheduler gives I/O-bound processes priority boosts when they wake from I/O waits, improving overall system throughput by overlapping CPU and I/O utilization.

User input triggers immediate scheduling in well-designed systems. When you move your mouse or type on the keyboard, hardware interrupts deliver these events to the OS. The scheduler should immediately schedule the process waiting for that input to process it without delay. Windows implements input boost where threads that process window messages receive temporary priority increases when user input arrives.

Animations and media playback require consistent, predictable scheduling. A video player needs to decode and display 60 frames per second—missing frame deadlines causes visible stuttering. The scheduler might give media processes small but frequent time slices at elevated priority to maintain smooth playback. Some systems provide special scheduling classes for multimedia applications.

Power vs. performance tradeoffs affect scheduling decisions differently for interactive and background work. Interactive processes need quick bursts of high performance, then the system can reduce power until the next user action. Background processes can often tolerate performance throttling to save power. Modern schedulers consider power states when making scheduling decisions, potentially consolidating work on fewer cores at higher frequencies for brief periods (race to idle—complete work quickly then sleep deeply) or spreading work across more cores at lower frequencies depending on workload characteristics.

Process States and State Transitions

Understanding process states and how processes transition between states is fundamental to understanding how scheduling works and when scheduling decisions occur.

The new state exists briefly when a process is first created. The operating system allocates process control block data structures and initializes process information but hasn’t yet admitted the process to the ready queue. This distinction allows the OS to limit the degree of multiprogramming (number of processes competing for CPU) by controlling admission to the ready queue.

The ready state means the process could execute productively if given CPU time but is currently waiting for the scheduler to select it. Processes enter the ready state when first admitted, when preempted from running state, or when transitioning from waiting to ready because a waited-for event occurred. The ready queue contains all ready processes, organized according to the scheduling algorithm.

The running state means the process is currently executing on a CPU core. The number of processes in the running state at any instant equals the number of available cores (on a quad-core system, at most four processes run simultaneously). Processes in the running state execute instructions until they block, their time quantum expires, or a higher-priority process preempts them.

The waiting or blocked state means the process cannot execute productively even if given CPU time because it’s waiting for some event—completion of I/O operation, availability of a resource held by another process, a timer to expire, or arrival of a signal. The scheduler never selects waiting processes because giving them CPU time would be wasteful. Processes transition from running to waiting when they request I/O or explicitly wait for an event. When the awaited event occurs, the OS moves the process from waiting to ready (not directly to running—it must wait its turn in the ready queue).

The terminated state indicates the process has finished execution. The OS deallocates most process resources but maintains some data structures until a parent process retrieves the termination status. On Unix-like systems, these lingering processes are called zombies—they’ve terminated but haven’t been fully reaped.

State transitions happen at specific moments. Running → Ready transitions occur on preemption (time quantum expires, higher-priority process arrives) and represent the core of preemptive scheduling. Running → Waiting transitions occur when the process requests I/O, waits for a lock, calls sleep, or otherwise blocks. Waiting → Ready transitions occur when the awaited event completes, triggered by interrupt handlers or other processes. Ready → Running transitions occur when the scheduler selects the process to execute. Running → Terminated occurs when the process calls exit or encounters a fatal error.

The scheduler runs at each transition involving the running state. When a process blocks (Running → Waiting), the scheduler immediately selects a new process from the ready queue to run. When a process is preempted (Running → Ready), the scheduler decides which process runs next (might be the same process, might be different). When a process terminates, the scheduler selects the next process. When a new process becomes ready, preemptive schedulers evaluate whether it should preempt the currently running process.

Blocked process tracking uses wait queues—lists of processes waiting for specific events. Each I/O device, synchronization primitive (lock, semaphore), or event has an associated wait queue. When a process blocks, it moves from the ready queue to the appropriate wait queue. When the event occurs, all processes on that wait queue move to the ready queue. This organization prevents the scheduler from wasting time examining processes that couldn’t run even if selected.

Scheduling Metrics and Performance Analysis

Operating systems measure scheduling performance through various metrics that quantify different aspects of scheduler effectiveness.

CPU utilization is the percentage of time the CPU spends executing processes rather than being idle. Higher utilization generally means better use of resources, though 100% utilization might indicate overload. The scheduler aims for high utilization while maintaining responsiveness.

Throughput measures the number of processes completed per unit time. Higher throughput means more work gets done. Batch processing systems prioritize throughput over response time, using algorithms and time quanta that minimize context switch overhead.

Turnaround time is the total time from process submission to completion—the interval from when a process enters the system until it terminates. Turnaround time includes time spent waiting in ready queue, executing on CPU, and waiting for I/O. Minimizing average turnaround time is often a goal, particularly for batch systems.

Waiting time is the total time a process spends in the ready queue waiting for CPU. This doesn’t include time spent waiting for I/O (which is in the waiting state, not ready state). Waiting time directly reflects how long processes wait for their turn, and minimizing it improves user-perceived responsiveness.

Response time measures the time from request submission to the first response, particularly relevant for interactive systems. Even if overall turnaround time is long, users are satisfied if the first response arrives quickly. Time-sharing systems prioritize response time, using algorithms like Round Robin that give all processes regular CPU access.

Fairness measures how evenly CPU time is distributed among processes. Perfect fairness means each process receives equal CPU time (or time proportional to its priority). Extreme unfairness (starvation) means some processes never or rarely receive CPU. The scheduler balances fairness against efficiency—pure fairness might not be optimal if it means frequently context switching between very different processes.

Context switch overhead is the time spent switching between processes—saving and restoring state, flushing caches, invalidating TLB entries. Since context switches don’t accomplish useful work, minimizing them (or at least ensuring time spent in useful work far exceeds time in context switches) is important. Time quantum size directly affects context switch frequency.

Scheduling latency is the time between when a process becomes ready and when it actually starts executing. Low latency is crucial for real-time systems and interactive applications. The scheduler’s complexity and the number of ready processes both affect latency.

Convoys or priority inversion occurrences indicate scheduling problems. Measuring how often high-priority processes wait for low-priority processes helps identify priority inversion issues that need addressing.

Real-world performance evaluation uses benchmarks that run representative workloads while measuring metrics. Synthetic benchmarks like SPEC CPU test processor and scheduler performance under controlled conditions. Real-world benchmarks run actual applications and measure responsiveness, throughput, and resource usage. Schedulers are tuned based on benchmark results to optimize for target workloads.

Scheduling in Special Contexts

Certain computing contexts require specialized scheduling approaches beyond general-purpose operating system scheduling.

Real-time systems have hard deadlines where missing a deadline causes system failure (hard real-time) or significant problems (soft real-time). Real-time scheduling algorithms like Rate-Monotonic Scheduling (RMS) or Earliest Deadline First (EDF) provide mathematical guarantees about deadline compliance. RMS assigns fixed priorities based on task period—shorter-period tasks get higher priority. EDF dynamically prioritizes tasks with nearest deadlines. These algorithms are analyzable—you can mathematically prove whether a task set will meet its deadlines, critical for safety-critical real-time systems.

Virtualization introduces additional scheduling layers. The hypervisor schedules virtual machines (VMs) onto physical CPU cores, and each VM’s guest OS schedules processes within the VM. This two-level scheduling requires coordination. The hypervisor might use proportional-share scheduling to divide CPU time among VMs according to configured shares. Credit-based scheduling, used by Xen, gives each VM CPU credits that deplete as it executes and regenerate over time, ensuring fair long-term allocation.

Container schedulers like Kubernetes must schedule containers (which are really just grouped processes) across cluster machines. These schedulers consider resource requirements, node capabilities, affinity rules, and availability zones when deciding which machine should run each container. Once scheduled to a machine, the Linux kernel’s process scheduler handles actual CPU allocation among container processes.

Batch processing systems prioritize throughput over responsiveness, using algorithms like FCFS or non-preemptive priority scheduling with large time quanta to minimize context switch overhead. Job scheduling systems like SLURM (used in high-performance computing) schedule batch jobs based on requested resources, estimated runtime, and user quotas.

Mobile and embedded systems face power constraints. Schedulers must balance performance and energy consumption. Heterogeneous Multi-Processing (HMP) uses CPU cores with different performance and power characteristics (like ARM big.LITTLE with power-efficient cores and high-performance cores). The scheduler moves tasks between core types based on workload—background tasks run on efficient cores, demanding tasks migrate to fast cores. Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) adjusts core voltage and clock speed based on load, with the scheduler influencing these decisions by consolidating work to enable aggressive downclocking.

GPU scheduling allocates GPU compute resources among processes wanting to use graphics cards for computation (GPGPU). Unlike CPU scheduling, GPU work often involves submitting compute kernels that run to completion rather than time-sliced scheduling. The GPU driver schedules kernel launches, managing queues of pending work from multiple processes.

Conclusion

CPU scheduling stands as one of the operating system’s most crucial responsibilities, determining which programs run when and for how long on the limited resource of processor time. From the simple conceptual elegance of First-Come First-Served to the sophisticated adaptiveness of modern multilevel feedback queues and Completely Fair Scheduler, scheduling algorithms have evolved to balance competing goals of fairness, responsiveness, throughput, and efficiency. The scheduler’s constant decision-making—thousands of times per second—creates the illusion of simultaneous execution that defines the modern computing experience, allowing you to watch videos, browse the web, and run background tasks all at the same time without perceiving that the CPU is actually rapidly switching between these programs.

Understanding CPU scheduling reveals how operating systems transform the raw capability to execute instructions into the managed, responsive, multi-program environment we rely upon. Whether you’re a developer optimizing application performance, a system administrator tuning server responsiveness, or a curious user wondering why some programs seem sluggish while others stay snappy, knowledge of scheduling principles provides insights into computer behavior and performance. As processors evolve with more cores, heterogeneous architectures combining different core types, and specialized accelerators for specific workloads, scheduling grows more complex, yet its fundamental purpose remains unchanged—fairly and efficiently distributing computation across programs to maximize both system performance and user satisfaction.

The modern scheduler must handle single-threaded legacy applications and massively parallel workloads, interactive GUI programs and background batch processing, real-time media playback and best-effort file transfers, all while considering power consumption, thermal limits, cache effects, and memory locality. That contemporary operating systems accomplish this so seamlessly, maintaining responsiveness even under heavy load, represents remarkable engineering achievement built on decades of research and refinement. The next time you notice your computer smoothly handling multiple demanding tasks simultaneously, you’re witnessing CPU scheduling in action—the invisible orchestrator that ensures every program gets its turn at the processor while maintaining the responsive, concurrent computing experience modern users expect and depend upon.

Summary Table: CPU Scheduling Algorithms Comparison

| Algorithm | Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Come, First-Served (FCFS) | Non-preemptive | Simple implementation, predictable order, low overhead | Convoy effect, poor average wait time, no support for priorities | Simple batch systems, within single priority level |

| Shortest Job First (SJF) | Non-preemptive | Optimal average wait time, minimizes turnaround for short processes | Requires knowing process length (impossible), starvation of long processes, not practical | Theoretical comparison baseline, some batch systems with known job lengths |

| Shortest Remaining Time (SRTF) | Preemptive | Better average wait time than SJF, responsive to new short jobs | Requires runtime prediction, more context switches, starvation risk | Theoretical optimization, rarely used in practice |

| Round Robin (RR) | Preemptive | Fair, good for interactive systems, prevents monopolization, predictable | Context switch overhead, performance depends on quantum size | Time-sharing systems, interactive workloads |

| Priority Scheduling | Both | Expresses importance differences, supports real-time needs, flexible | Starvation without aging, priority inversion issues | Systems with clear priority distinctions, real-time components |

| Multilevel Queue | Both | Different algorithms for different process types, organized structure | Inflexible, processes can’t change queues, risk of starvation | Systems with distinct process classes (foreground/background) |

| Multilevel Feedback Queue | Preemptive | Adaptive to process behavior, balances interactive and batch, prevents starvation through aging | Complex implementation, many tunable parameters, harder to predict | General-purpose operating systems (Windows, traditional Unix) |

| Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) | Preemptive | True fairness, automatic load balancing, efficient with red-black tree, scalable | Complex implementation, may not optimize for specific workloads | Modern Linux systems, servers and desktops |

| Real-Time Scheduling (EDF, RMS) | Preemptive | Deadline guarantees, mathematically analyzable, predictable | Requires known task characteristics, can’t handle overload gracefully | Real-time systems, embedded systems, safety-critical applications |

Key Scheduling Metrics:

| Metric | Definition | Formula | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU Utilization | Percentage of time CPU is busy | (Busy Time / Total Time) × 100% | Maximize (but not always 100%) |

| Throughput | Processes completed per unit time | Completed Processes / Time | Maximize |

| Turnaround Time | Time from submission to completion | Completion Time – Arrival Time | Minimize |

| Waiting Time | Time spent in ready queue | Turnaround Time – Burst Time – I/O Time | Minimize |

| Response Time | Time to first response | First CPU Time – Arrival Time | Minimize (especially for interactive) |

| Fairness | Evenness of CPU distribution | Variance or coefficient of variation of CPU time | Balance with efficiency |