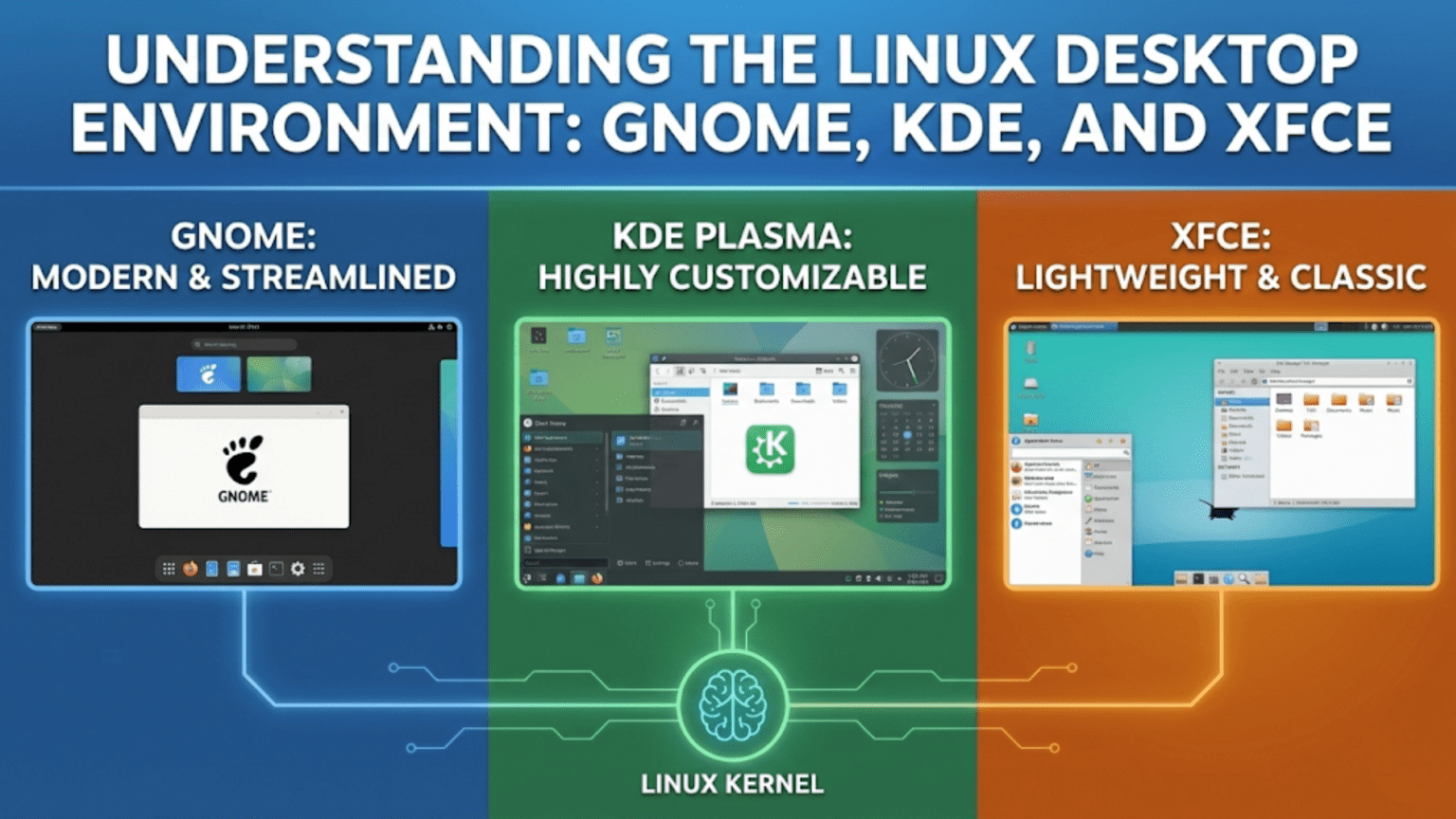

A Linux desktop environment is a complete graphical user interface that provides everything you see and interact with on screen — windows, menus, icons, panels, file managers, and system settings. Unlike Windows or macOS, Linux separates the desktop environment from the operating system itself, meaning users can freely choose or switch between environments. The three most widely used Linux desktop environments are GNOME, KDE Plasma, and XFCE, each with a distinct philosophy, appearance, and resource footprint.

Introduction: The Face of Your Linux System

When most people imagine an operating system, they picture the visual experience: the desktop background, the windows that open applications, the taskbar or dock at the screen’s edge, the menus and icons that let them navigate their files and launch programs. In Windows and macOS, this visual layer is inseparable from the operating system itself — you cannot replace the Windows desktop with something entirely different without replacing Windows. In Linux, everything works differently.

Linux’s architecture separates the operating system’s core functions from the visual interface placed on top of them. The Linux kernel and system libraries do their work invisibly, managing hardware and running programs. Entirely separate software — the desktop environment — provides the graphical experience. This separation means you have a choice that simply does not exist in any other mainstream operating system: you can choose which desktop environment you use, switch between them freely, and customize the visual experience of your Linux system down to extraordinarily fine detail.

This freedom is one of Linux’s most powerful features, but it can also be one of its most confusing aspects for newcomers. When you install Ubuntu, you get GNOME. When you install Linux Mint, you get Cinnamon by default. When you install Kubuntu (the KDE flavor of Ubuntu), you get KDE Plasma. These are not different operating systems — they are different visual interfaces running on the same underlying Ubuntu base. Understanding what desktop environments are, how they differ, and which one suits your needs will help you make a more informed choice and get more from your Linux experience.

This article focuses on the three most prominent and widely used Linux desktop environments: GNOME, KDE Plasma, and XFCE. We will explore each in depth — their history, design philosophy, interface structure, resource requirements, customization capabilities, and the types of users each serves best. Along the way, we will also briefly cover several other notable desktop environments and touch on an even more fundamental layer: window managers.

What Exactly Is a Desktop Environment?

Before comparing specific desktop environments, it is worth understanding precisely what a desktop environment is and what components it comprises.

The Stack of Visual Components

A Linux desktop environment is not a single program but a collection of tightly integrated components that together create a complete graphical computing experience.

The display server is the foundation of all graphical output on Linux. It manages the screen, accepts input from keyboards and mice, and provides an interface through which graphical applications can draw windows. The traditional display server on Linux has been X.Org (commonly called X11), which has been in use for decades. Wayland is a modern replacement that offers better security, smoother animation, and improved support for high-DPI displays. Most major desktop environments now support both, with Wayland becoming the default on distributions like Fedora and Ubuntu.

The window manager is the component that draws the decorative borders around windows (title bars, close/minimize/maximize buttons), handles how windows are resized and moved, and manages which window appears in front of which. In a full desktop environment, the window manager is included and integrated. Users who want a minimal setup can run a standalone window manager without any desktop environment — but this is an advanced approach well outside the scope of beginner setups.

The panel or taskbar is the bar (or bars) that typically runs along one or more edges of the screen, showing the clock, system tray notifications, open application indicators, workspace switchers, and application launchers. Different desktop environments implement this differently — some use a single bottom panel like Windows, others use a top bar only, others use a dock-and-bar combination.

The file manager provides graphical browsing of files and folders. GNOME uses Nautilus (also called Files), KDE uses Dolphin, and XFCE uses Thunar. These file managers vary considerably in their features, interface style, and integration with the rest of the desktop.

The settings application provides a graphical interface for configuring the system — display settings, networking, Bluetooth, sound, power management, user accounts, and many other options. The comprehensiveness and organization of the settings application differs substantially between desktop environments and significantly affects the user experience.

System utilities round out the desktop environment: a text editor, terminal emulator, image viewer, archive manager, screen lock, login manager, and many other supporting applications. While you can mix components from different desktop environments, using a cohesive set from a single environment provides the most consistent visual experience.

How Desktop Environments Relate to Distributions

An important point for new Linux users: a desktop environment is not the same as a Linux distribution. Ubuntu is a distribution; GNOME is a desktop environment that Ubuntu ships by default. You can install KDE Plasma on Ubuntu just as easily as on any other distribution. Many distributions offer multiple official “flavors” or “spins” that package the same underlying distribution with different desktop environments.

This means your choice of desktop environment and your choice of distribution are somewhat independent decisions — you can mix and match, within the constraints of what is officially supported and well-maintained for each distribution.

GNOME: Modern, Focused, and Opinionated

GNOME (GNU Network Object Model Environment) is the most widely deployed Linux desktop environment, used as the default on Ubuntu, Fedora, Debian, and many other major distributions. It is developed by the GNOME Project, an international community effort that began in 1997 as a free alternative to the proprietary KDE desktop of that era.

Design Philosophy

GNOME’s design is guided by a set of Human Interface Guidelines (HIG) that prioritize simplicity, focus, and distraction-free computing. The GNOME team’s philosophy holds that a desktop environment should get out of the user’s way — providing the tools needed to do work without cluttering the interface with options, controls, and visual noise. This philosophy leads to deliberate design choices: fewer visible options, more automatic behavior, and a cleaner interface that removes elements deemed unnecessary.

This approach has made GNOME one of the most consistently criticized and praised desktop environments simultaneously. Users who appreciate its clean aesthetics and keyboard-driven workflow love it deeply. Users who prefer fine-grained control over every visual element and behavior find it frustratingly restrictive. Understanding this tension is key to knowing whether GNOME suits you.

The GNOME Interface Structure

GNOME’s interface breaks from the traditional desktop metaphor that Windows popularized. There is no permanently visible taskbar at the bottom of the screen showing all running applications. Instead, GNOME uses:

The Activities Overview is central to GNOME’s workflow. Accessed by clicking “Activities” in the top left corner, pressing the Super key (the Windows key on most keyboards), or moving the cursor to the top-left hot corner, the Activities Overview reveals a zoomed-out view of all open windows, a search bar at the top, and a workspace switcher on the right side. You can search for applications, files, settings, and even web results from this single interface. GNOME encourages users to work primarily through the Activities Overview rather than a traditional application menu.

The top bar runs across the top of the screen, showing the application menu (for the currently focused application, similar to macOS’s menu bar), a centered clock, and a combined system status area in the top right that shows notifications, network status, volume, battery, and quick settings.

The dock appears along the left side of the screen (in Ubuntu’s customized GNOME) or only in the Activities Overview (in stock GNOME) showing pinned and running applications.

Workspaces in GNOME are dynamic — new workspaces are created automatically as you fill existing ones with windows, and empty workspaces are removed. This encourages organizing work across multiple virtual desktops, each containing a different task or project.

GNOME Applications

GNOME ships with a cohesive suite of applications designed to match its interface style. Nautilus (Files) is the file manager, with a clean interface that prioritizes usability over feature density. GNOME Text Editor is a modern, simple text editor. GNOME Terminal provides a clean terminal emulator. The GNOME Calculator, Calendar, Contacts, Maps, Music, and Photos applications follow consistent design patterns. All of these applications use the GTK toolkit, which gives them a consistent look and behavior.

Customization in GNOME

GNOME’s default configuration offers limited visible customization options — deliberately so, in line with its simplicity philosophy. However, GNOME’s extension system provides a powerful mechanism for adding features and changing behaviors. GNOME Extensions are small add-ons that can modify virtually any aspect of the desktop: adding a traditional bottom taskbar, enabling a Dash to Dock extension for a macOS-like dock, adding a clipboard manager, configuring window snapping behaviors, and hundreds of other modifications.

Extensions are installed through the GNOME Extensions website (extensions.gnome.org) using a browser integration. The GNOME Tweaks application provides additional settings not exposed in GNOME’s standard Settings application, including font configuration, animation speed, window controls placement, and startup application management.

Resource Usage

GNOME is the most resource-intensive of the three desktop environments covered here. A fresh GNOME session typically uses approximately 700 MB to 1.2 GB of RAM at idle, depending on the specific version and distribution. On modern computers with 8 GB or more of RAM, this is not a practical concern. On systems with 4 GB or less, GNOME’s memory consumption can meaningfully affect performance, particularly when multiple memory-intensive applications are running simultaneously.

Who Should Use GNOME

GNOME suits users who appreciate clean, modern aesthetics and are willing to adapt to a non-traditional workflow. Its keyboard-centric design particularly rewards users who spend significant time in the terminal or in full-screen applications and want minimal visual distraction. Developers who use Linux as their primary work environment frequently choose GNOME for its clean workspace management and excellent touchpad gesture support on laptops.

KDE Plasma: Powerful, Customizable, and Feature-Rich

KDE Plasma (commonly referred to simply as KDE) is GNOME’s primary rival for the most widely used Linux desktop environment. Developed by the KDE Community, Plasma represents a fundamentally different philosophy from GNOME: rather than simplifying the interface by removing options, KDE embraces configurability, giving users control over nearly every aspect of the desktop experience.

History and Philosophy

KDE was founded in 1996 by German student Matthias Ettrich, predating GNOME. The original KDE was built on the Qt framework, which at the time had licensing restrictions that prompted the creation of GNOME as a fully free alternative. Qt’s licensing was subsequently improved, and both KDE and GNOME now use fully open source versions of their respective toolkits.

KDE Plasma (the current version of KDE’s desktop) was substantially rewritten as version 5 in 2014, then underwent another major revision to Plasma 6 in 2024. The redesign brought dramatic improvements in performance and visual consistency while retaining the breadth of customization that defines the KDE experience.

KDE’s philosophy is sometimes summarized as “simple by default, powerful when you need it.” The default KDE Plasma desktop is organized and accessible enough for new users, but every element can be configured, moved, resized, replaced, or removed by users who want to tailor the environment precisely to their preferences.

The KDE Plasma Interface Structure

KDE Plasma’s default layout feels immediately familiar to users coming from Windows:

The panel runs along the bottom of the screen. On the left side is the Application Launcher (the KDE equivalent of a Start menu), which opens a searchable grid of installed applications organized by category. In the center is the taskbar showing running applications and their windows. On the right side is the system tray showing network status, volume, battery, clock, and notifications.

The desktop supports widgets — small interactive applications that can be placed directly on the desktop background. These range from a simple clock widget to weather displays, system monitors, sticky notes, and many others. Widgets can also be added to panels, giving you highly configurable information displays.

Activities in KDE are a powerful but often underused feature — separate desktop configurations that can have different wallpapers, different panel layouts, and different sets of widgets. Activities allow truly different working environments for different roles or projects, switchable from the taskbar or a keyboard shortcut.

Virtual desktops in KDE work alongside Activities, providing multiple workspaces within each Activity. Unlike GNOME’s dynamic workspaces, KDE’s virtual desktops are fixed in number and can be arranged in a grid.

KDE Applications

The KDE ecosystem includes a comprehensive suite of applications, all built with the Qt framework and following KDE’s Human Interface Guidelines. Dolphin is the KDE file manager, widely considered the most feature-rich Linux file manager, supporting split views, tabbed browsing, embedded terminal access, powerful batch renaming, and extensive network filesystem support. Kate is KDE’s advanced text editor with syntax highlighting, plugin support, and multi-document management. Konsole is the KDE terminal emulator. KMail, KOrganizer, and Kontact provide email, calendar, and personal information management.

The KDE Connect application deserves special mention: it integrates your Android smartphone with your KDE desktop, enabling shared clipboard, phone notification mirroring, remote control, file transfer, and more directly from the desktop. KDE Connect also works with GNOME and other desktop environments but is most deeply integrated with Plasma.

Customization in KDE

KDE Plasma’s customization capabilities are extraordinary — arguably more extensive than any other mainstream desktop environment. Right-clicking on the desktop or panel reveals Edit Mode, which allows adding, removing, moving, and resizing widgets. The System Settings application contains dozens of configuration categories covering desktop theme, icons, cursors, fonts, window decorations, taskbar behavior, keyboard shortcuts, touchpad gestures, display arrangement, and much more.

KDE’s theming system allows complete visual overhauls through Global Themes, which bundle together a plasma theme (panel and widget appearance), an application color scheme, window decoration style, icon set, and cursor theme. Switching global themes transforms the entire desktop appearance in seconds. The KDE Store (store.kde.org) hosts thousands of community-created themes, widgets, window decorations, and icon sets available for one-click installation.

Window management in KDE includes features like window tiling (automatically arranging windows in side-by-side or quadrant layouts), window-specific rules (always open this application on workspace 2, maximize this application on launch, always keep this window on top), and a window effects compositor that provides smooth animations and visual effects.

Resource Usage

A significant evolution in KDE Plasma’s story over the past decade has been its resource efficiency. Earlier versions of KDE were notorious for heavy RAM usage, but KDE Plasma 5 and 6 have become genuinely lightweight. A fresh Plasma session typically uses approximately 400–600 MB of RAM at idle — less than GNOME. This makes KDE Plasma an excellent choice for systems with limited RAM that still want a feature-rich, visually polished desktop.

Who Should Use KDE Plasma

KDE Plasma suits users who want maximum control over their desktop environment and are willing to invest time exploring its configuration options. Users coming from Windows will find KDE’s taskbar-centric layout immediately familiar. Users who appreciate visual customization — changing themes, colors, and layouts to match their preferences — will find KDE’s theming capabilities unmatched. Power users who want to configure specific application window behaviors, keyboard shortcuts, and workflow automation will find KDE’s rule systems invaluable.

KDE is also an excellent choice for users who initially found GNOME’s departures from convention frustrating. The more traditional workflow model and familiar interface paradigm often makes the transition from Windows smoother with KDE than with GNOME.

XFCE: Lightweight, Traditional, and Reliable

XFCE (sometimes spelled Xfce) occupies a distinct position in the desktop environment landscape: it is the leading lightweight desktop that still provides a complete, polished graphical experience. Where GNOME pushes the boundaries of modern interface design and KDE maximizes features, XFCE optimizes for speed and low resource usage while maintaining the traditional desktop metaphor that many users prefer.

History and Philosophy

XFCE was created by Olivier Fourdan in 1996, originally as a free alternative to the Common Desktop Environment (CDE) used on commercial Unix systems. The name originally stood for XForms Common Environment, though XFCE has not used the XForms toolkit for many years. Development is community-driven with no single corporate backer.

XFCE’s philosophy centers on three principles: being fast and lightweight, visually appealing, and easy to use. XFCE achieves its low resource footprint not by removing features carelessly but by implementing features efficiently and avoiding unnecessary complexity. The development pace is deliberately conservative — XFCE does not rush to adopt every new technology, preferring stability and reliability.

This conservatism is occasionally criticized as slow development, but it is also what makes XFCE the reliable choice for users who want a desktop that simply works and does not change dramatically from version to version.

The XFCE Interface Structure

XFCE uses a traditional desktop layout:

The panel (or panels — XFCE supports multiple panels) can be placed anywhere on screen. The default configuration typically features a top panel with an application menu (Whisker Menu, a searchable application launcher added by most distributions), window buttons showing running applications, and a system tray on the right with clock, volume, and network status.

The desktop itself supports right-click menus and can display file icons, allowing traditional desktop file management if desired. XFCE’s desktop component, xfdesktop, is separate from the file manager, meaning the desktop and file manager operate independently.

The window manager in XFCE is called XFWM4, a lightweight but fully capable window manager that handles window placement, focusing, and decorations. It includes a basic compositor for optional transparency and shadow effects, configurable to taste.

XFCE Applications

XFCE’s application suite includes Thunar (a fast, clean file manager with custom action support that allows adding user-defined operations to the right-click menu), Mousepad (a simple text editor), the XFCE Terminal, Ristretto (image viewer), and several utility applications. XFCE applications are built with GTK and have a consistent if relatively plain visual style.

One of XFCE’s notable characteristics is that it mixes well with applications from other desktop environments. Many XFCE users complement the XFCE base with GNOME or KDE applications where more features are needed — for example, using Dolphin instead of Thunar for file management, or GNOME’s Gedit text editor instead of Mousepad. Because Linux applications can run across desktop environments (they just may not match the visual theme perfectly), this mixing is entirely practical.

Customization in XFCE

XFCE offers meaningful customization through its Settings Manager, which provides configuration panels for appearance (GTK themes, icon themes, fonts), window manager behavior, panel layout, keyboard shortcuts, display settings, and more. The customization depth sits between GNOME’s minimal defaults and KDE’s exhaustive options.

XFCE’s panel is particularly flexible — panels can be added, positioned anywhere on screen, and populated with a wide range of plugins including application launchers, workspace switchers, battery indicators, CPU monitors, weather displays, and many others. This makes XFCE panels highly configurable without the complexity of KDE’s widget system.

The ability to apply GTK themes to XFCE means that nearly all GTK-based themes designed for GNOME also work beautifully on XFCE, giving access to the large community of GTK theme creators even though XFCE is a different desktop environment.

Resource Usage

XFCE’s primary advantage is its exceptional resource efficiency. A fresh XFCE session typically uses approximately 200–350 MB of RAM at idle — roughly half of KDE Plasma and a third of GNOME. This makes XFCE the practical choice for computers with 2–4 GB of RAM, for virtual machines where resources are constrained, or for users who simply want to maximize the resources available to their applications rather than their desktop.

XFCE also starts faster than both GNOME and KDE, making it pleasant on older solid-state drives or spinning hard disks where startup time is more noticeable.

Who Should Use XFCE

XFCE suits users with older or lower-powered hardware, users who prioritize stability and predictability over cutting-edge features, and users who prefer the traditional desktop paradigm (taskbar at top or bottom, desktop icons, traditional application menu) without the resource overhead of KDE Plasma.

XFCE is also an excellent choice for users running Linux in virtual machines, on single-board computers like the Raspberry Pi, or in environments where minimal resource consumption is important. Many experienced Linux users who have tried multiple desktop environments return to XFCE for its reliable simplicity and efficiency.

Desktop Environment Comparison at a Glance

| Feature | GNOME | KDE Plasma | XFCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default RAM usage | ~700–1200 MB | ~400–600 MB | ~200–350 MB |

| Default layout style | Modern / non-traditional | Traditional (Windows-like) | Traditional |

| Customization level | Low (with extensions) | Very High | Moderate |

| Application toolkit | GTK | Qt | GTK |

| Wayland support | Excellent (default) | Good (improving) | Partial (X11 primary) |

| Best for | Modern workflows, laptops | Power users, Windows migrants | Older hardware, simplicity |

| Learning curve | Moderate (different workflow) | Low (familiar layout) | Low |

| Included apps quality | High (cohesive) | High (feature-rich) | Moderate (lightweight) |

| Extension/plugin system | GNOME Extensions | KDE Store widgets | Panel plugins |

| Active development pace | Fast | Fast | Moderate/conservative |

Other Notable Desktop Environments

While GNOME, KDE Plasma, and XFCE are the three most significant options, several other desktop environments are worth knowing about.

Cinnamon

Cinnamon was developed by the Linux Mint project as a fork of GNOME 3 that preserved the traditional desktop metaphor that GNOME 3 had abandoned. Cinnamon provides a taskbar-centric layout, a traditional application menu (the Cinnamon Menu), and familiar window management behavior, making it extremely welcoming to Windows users. Cinnamon is GTK-based and uses a moderate amount of resources — more than XFCE but less than full GNOME. It is exclusively used as the default desktop of Linux Mint, though it can be installed on other distributions.

MATE

MATE is a continuation of GNOME 2 — the older, traditional GNOME interface that was replaced by the GNOME 3 redesign in 2011. When GNOME 3 changed direction so dramatically, many users who preferred the classic GNOME 2 interface forked it and continued development as MATE. MATE is very lightweight (comparable to XFCE), uses a classic two-panel layout by default, and provides a familiar traditional desktop. Ubuntu MATE is an official Ubuntu flavor built around it.

LXQt

LXQt is an ultra-lightweight desktop environment that emerged from the merger of two earlier minimal projects: LXDE and Razor-qt. Built on Qt (like KDE) but designed to consume minimal resources, LXQt uses even less RAM than XFCE while still providing a complete desktop experience. It is an excellent choice for very old hardware or environments where absolute minimal resource consumption is the priority.

Budgie

Budgie is a modern desktop environment developed by the Solus Linux project. It provides a clean, refined interface with a macOS-inspired Raven sidebar for notifications and applets, a polished GNOME-integrated experience, and a focus on elegant simplicity without GNOME’s workflow departures. Budgie is available as an Ubuntu Budgie flavor and is growing in popularity among users who want a contemporary, visually refined desktop.

Switching Desktop Environments: Is It Possible?

One of Linux’s great freedoms is the ability to switch desktop environments without reinstalling your operating system. If you install Ubuntu (which comes with GNOME) and later decide you prefer KDE Plasma, you can install KDE Plasma directly on your existing Ubuntu system.

On Ubuntu, installing KDE Plasma is as simple as:

sudo apt install kubuntu-desktopInstalling XFCE on Ubuntu:

sudo apt install xubuntu-desktopAfter installation, log out and look for a session selector at the login screen (usually a gear icon or session menu near the password field). Select your new desktop environment and log in.

This flexibility is powerful, but a few caveats apply. Installing multiple desktop environments on the same system adds applications from each environment, which can create a somewhat cluttered application menu with duplicate tools (two file managers, two text editors, etc.). It also adds packages that consume disk space. Some users prefer to maintain clean, single-desktop setups. Others happily use multiple environments on the same installation and switch based on their needs or mood.

If you want to try a different desktop environment without affecting your installed system, most distributions offer live USB versions of their alternative desktop flavors. Booting Ubuntu’s Kubuntu flavor from a USB drive lets you experience KDE Plasma before deciding whether to install it.

Choosing the Right Desktop Environment for You

With a thorough understanding of the three main options, the decision framework becomes clear.

If your hardware is newer (made in the last five years with 8 GB or more of RAM) and you appreciate modern design sensibility, GNOME offers a refined, cohesive experience. The initial learning curve of adapting to the Activities Overview workflow is real but short — most users find it natural within a week. GNOME particularly shines on laptops with good touchpad support and HiDPI displays.

If you are migrating from Windows and want your desktop to feel immediately familiar, or if you love tweaking your environment and want maximum control over every visual element, KDE Plasma delivers the most feature-rich experience of any mainstream desktop environment. Its resource efficiency means it runs well even on older hardware, and its customization depth means you can make it look and behave exactly as you want.

If your hardware is older (4 GB of RAM or less, or a computer more than eight years old), or if you simply want a fast, stable, no-nonsense desktop that gets out of your way and uses minimal resources, XFCE is the right choice. Its traditional layout, reliable behavior, and exceptional efficiency make it the trusted workhorse of the Linux desktop world.

And if none of these feels right, Cinnamon, MATE, LXQt, and Budgie each offer compelling alternatives worth exploring. The beauty of the Linux desktop environment ecosystem is that trying different options costs nothing — download a different flavor’s live USB, boot it up, and spend an hour with it before deciding.

Conclusion: Freedom to Choose Your Computing Environment

The Linux desktop environment ecosystem represents something unique in the history of personal computing: genuine user choice over the fundamental nature of the graphical interface. No other mainstream operating system offers this freedom. You are not locked into the aesthetic and workflow decisions of a single company. You can choose the interface that matches your hardware, your workflow, your visual preferences, and your philosophy.

GNOME brings modern design and a focused workflow that suits users who want an interface that confidently makes choices on their behalf. KDE Plasma brings extraordinary power and configurability that suits users who want their desktop to work exactly as they specify. XFCE brings efficient, reliable simplicity that suits users who value speed and stability above feature richness.

Understanding these three desktop environments — their strengths, their resource requirements, their customization capabilities, and their target users — gives you the foundation to make an informed choice and get the most from your Linux experience. Your desktop environment is the face of your computing life. In Linux, that face is yours to choose.